Abstract

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) bacteria are foodborne pathogens responsible for diarrhea and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). Shiga toxin, the main STEC virulence factor, is encoded by the stx gene located in the genome of a bacteriophage inserted into the bacterial chromosome. The O26:H11 serotype is considered to be the second-most-significant HUS-causing serotype worldwide after O157:H7. STEC O26:H11 bacteria and their stx-negative counterparts have been detected in dairy products. They may convert from the one form to the other by loss or acquisition of Stx phages, potentially confounding food microbiological diagnostic methods based on stx gene detection. Here we investigated the diversity and mobility of Stx phages from human and dairy STEC O26:H11 strains. Evaluation of their rate of in vitro induction, occurring either spontaneously or in the presence of mitomycin C, showed that the Stx2 phages were more inducible overall than Stx1 phages. However, no correlation was found between the Stx phage levels produced and the origin of the strains tested or the phage insertion sites. Morphological analysis by electron microscopy showed that Stx phages from STEC O26:H11 displayed various shapes that were unrelated to Stx1 or Stx2 types. Finally, the levels of sensitivity of stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 to six Stx phages differed among the 17 strains tested and our attempts to convert them into STEC were unsuccessful, indicating that their lysogenization was a rare event.

INTRODUCTION

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) bacteria of various serotypes, including O157:H7, are foodborne pathogens responsible for human infections ranging from mild watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis, which may be complicated by hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which is sometimes fatal. Domestic ruminants, especially cattle, are a major reservoir of STEC, whose transmission to humans occurs through the ingestion of food or water and through direct contact with animals or their environment. STEC O26:H11 was first identified as a cause of HUS in 1983 (1, 2). O26:H11 is the most commonly isolated non-O157:H7 serotype in Europe, accounting for 12% of all clinical enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) isolates in 2012 (3, 4). Since the early 2000s, a significantly increasing proportion of HUS cases caused by non-O157 serogroups was identified in France, with serogroup O26 accounting for 11% of cases for the period 1996 to 2013 (5). This serogroup also accounted for 22% of clinical non-O157 EHEC isolates in the United States during the period between 1983 and 2002 (6). STEC O26:H11 has been detected in meat and dairy products (7–9). At the end of 2005, STEC O26:H11 was involved in an outbreak in France that included 16 HUS cases and was linked to consumption of contaminated unpasteurized Camembert cheese (10). Another outbreak of STEC O26:H11 occurred in Denmark in 2007 and was caused by beef sausage. Twenty cases of diarrhea, the majority of which occurred in children (average age, 2 years), were reported (11).

Shiga toxins (Stx) are considered the major virulence factor of STEC, and stx genes are located in the genome of temperate bacteriophages (Stx phages) inserted as prophages into the STEC chromosome (12–14). There are two Stx groups, Stx1 and Stx2, divided into 3 (a, c, and d) and 7 (a to g) subtypes, respectively (15). Stx1 and Stx2 can be produced either singly or together by STEC O26:H11 (6), and STEC strains carrying the stx2 gene only are generally associated with a more severe clinical outcome than STEC possessing the stx1 gene (16). The first Stx1 phage described was phage H19B, which was isolated from a clinical EHEC O26 strain (12). In the 1990s, a shift of the stx genotype, from isolates carrying stx1 to isolates possessing the stx2 gene either alone or together with stx1, was observed in Germany in EHEC O26:H11 (17, 18). More recently, a panel of 74 STEC O26:H11 strains of various origins was characterized and the results showed that the majority of food and cattle strains possessed the stx1a subtype whereas human strains carried mainly stx1a or stx2a (19).

Stx phages insert their genome into specific sites in the bacterial chromosome, where they remain silent (20), allowing their bacterial hosts to survive as lysogenic strains. The main Stx phage insertion sites in STEC O26:H11 were the wrbA and yehV genes followed distantly by yecE and sbcB (19). Stx phages are inducible from their host strain by DNA-damaging agents such as antibiotics (21, 22). DNA damage triggers the SOS response of E. coli (23), resulting in the derepression of phage lytic genes, lysis of the bacterial host cells, and release of the phage particles. In addition, other conditions such as UV irradiation (24) or high hydrostatic pressure treatment (25) were also shown to induce Stx phages. Stx phage induction is an important feature of STEC as it is closely linked to Stx production (26).

STEC O26:H11 bacteria have the characteristic of frequent loss and acquisition of Stx phages (27, 28). The acquisition of an Stx phage by stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 has been demonstrated in vitro (13, 27). The Stx1 H-19B phage can also be transferred in vivo in mice from donor STEC O26:H11 to an E. coli recipient strain (29). Stx phage transfer can result in the emergence of new highly pathogenic strains as illustrated by the recent outbreak in Germany in 2011, with nearly 4,000 humans infected, including 900 HUS cases and 50 deaths (30), which was caused by an enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strain lysogenized with an Stx phage (31). Phage-mediated transfer of the stx2 gene to E. coli has also been shown to occur in food and water samples (32). In contrast, loss of Stx phage by STEC O26:H11 can generate stx-negative E. coli derivative strains which might interfere in the detection of STEC O26:H11, especially when they are isolated from food samples initially identified as stx-positive by PCR. Except for the absence of the stx gene, these strains are similar to STEC O26:H11 and are referred to as “attaching/effacing E. coli” (AEEC) O26:H11. Madic et al. have demonstrated the presence of STEC and AEEC O26:H11 in raw milk cheese samples (33). Monitoring plans carried out in France between 2007 and 2009 also showed the presence of STEC and AEEC in raw milk cheeses, including serotype O26:H11 (34). Finally, Trevisani et al. also revealed the presence of both stx-positive and stx-negative E. coli O26 strains in milk samples (0.4% and 2% of the samples, respectively) or filters (0.4% and 0.9% of the filters, respectively) (35). The fact that stx-negative E. coli (or AEEC) O26:H11 strains could be isolated from stx-positive food samples raises some questions about the diagnostic result since the possibility that these strains are derivatives of STEC that have lost their Stx phage and hence their stx gene during the enrichment procedure or isolation step cannot be excluded. Moreover, Stx phages have also been detected in beef and salad, which may also confound STEC screening methods based on PCR detection of the stx gene in food samples (36).

The main objective of this study was to explore the relationship between STEC O26:H11 strains and their stx-negative counterparts by focusing on Stx phages whose gain or loss mediates bidirectional conversion. We first addressed whether dairy and human strains could differ in their Stx prophage induction rates, which could be indicative of differential toxin levels and, potentially, of differential levels of virulence. We also addressed whether Stx phages from STEC O26:H11 differentially infect and convert dairy and human stx-negative E. coli strains. With this aim, the diversity and mobility of Stx phages previously identified among STEC O26:H11 strains (19) were evaluated. Levels of Stx phage induction were compared between clinical and dairy STEC O26:H11 strains containing stx prophages inserted into various locations. This comparison was performed in the presence and absence of mitomycin C (MMC), an antibiotic known to effectively induce Stx phages (37). The sensitivity of stx-negative E. coli isolates to the Stx phages released from STEC O26:H11 was investigated in addition to their lysogenic conversion. Finally, the morphology of Stx phages was studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Fourteen STEC O26:H11 isolates collected from humans (n = 9) and dairy products (n = 5) and 17 stx-negative O26:H11 E. coli isolates collected from humans (n = 8) and dairy products (n = 9) were used in this study (Table 1). E. coli K-12 strains DH5α and MG1655 were also used in this study (Table 1). The human and dairy STEC strains contained stx1 (n = 3 of each) or stx2 (n = 4 and n = 1, respectively) or both stx1 and stx2 genes (n = 2 and n = 1, respectively). E. coli strains were cultivated in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Panel of stx-positive and stx-negative Escherichia coli strains

| Origina | Strain | Stx phage type(s) | Insertion site(s) of Stx phage(s)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| STEC O26:H11 | |||

| Dairy product | 2976-1 | Stx1a | yehV |

| Dairy product | 10d | Stx1a | wrbA |

| Dairy product | 09QMA277.2 | Stx1a, Stx2a | yehV (Stx1), wrbA (Stx2) |

| Dairy product | 09QMA245.2 | Stx1a | yecE |

| Dairy product | F46-223 | Stx2a | wrbA |

| Human (NK) | VTH7 | Stx1a | sbcB |

| Human (D) | H19 | Stx1a | yehV |

| Human (HUS) | 3901/97 | Stx1a, Stx2a | wrbA (Stx1), yecE (Stx2) |

| Human (HUS) | 11368 | Stx1a | wrbA |

| Human (HUS) | 3073/00 | Stx1a, Stx2a | yehV (Stx1), yecE (Stx2) |

| Human (HUS) | 5917/97 | Stx2a | wrbA |

| Human (HUS) | 29348 | Stx2a | wrA |

| Human (HUS) | 31132 | Stx2a | yecE |

| Human (HUS) | 21765(1) | Stx2a | yecE |

| stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 | |||

| Dairy product | 09QMA04.2 | ||

| Dairy product | 09QMA315.2 | ||

| Dairy product | 09QMA306.D | ||

| Dairy product | FR14.18 | ||

| Dairy product | 4198.1 | ||

| Dairy product | 191.1 | ||

| Dairy product | 64.36 | ||

| Dairy product | 09QMA355.2 | ||

| Dairy product | F61-523 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 5021/97 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 5080/97 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 318/98 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 21474 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 21766 | ||

| Human (NK) | MB04 | ||

| Human (NK) | MB01 | ||

| Human (HUS) | 29690 | ||

| Other E. coli | |||

| K-12 | DH5α | ||

| K-12 | MG1655 |

D, diarrhea; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; NK, not known.

Previously described (19).

Bacteriophage induction.

A culture of STEC O26:H11 grown overnight was inoculated at 2% in a fresh LB medium with 5 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 37°C (38). When the culture reached the exponential-growth phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.3) (26), it was divided into two subcultures, A and B. In subculture A, mitomycin C (MMC) was added to give a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml (26). Subculture B, without MMC, was used to evaluate the spontaneous induction of Stx phages. Cultures were then further incubated overnight at 37°C with shaking at 240 rpm. After incubation, the rate of phage production was evaluated by measuring with a spectrophotometer the optical density at 600 nm of induced and noninduced cultures. All cultures were centrifuged at 7,200 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were filtered through low-protein-binding 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane filters (Millex-GP PES; Millipore) for phage purification.

Enumeration and isolation of Stx phages by double-agar overlay plaque assay.

E. coli DH5α and MG1655 were used as host strains to screen for the presence of bacteriophages. The suspensions of phage particles obtained after induction (see above) were diluted 10-fold. Two hundred microliters of an overnight culture of the host strain was mixed with 100 μl of each diluted phage suspension and incubated 1 h at 37°C. This mixture was added to molten LB top agarose (LB modified broth with agarose at 2 g/liter, 10 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM MgSO4), which was immediately poured onto LB-agar plates and allowed to solidify. After incubation for 18 to 24 h at 37°C, the plates were examined for the presence of lysis zones. Plaques were counted to determine the titer of the original phage preparation in PFU counts per milliliter by using the following calculation: number of plaques × 10 × the inverse of the dilution factor value (39).

Quantification of Stx phage by qPCR.

Filtered supernatants obtained after Stx phage induction were treated with DNase using a Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion; Life Technologies). Removal of any contaminating genomic DNA by DNase was verified by detection of the chromosomal STEC O26:H11 eae gene by quantitative PCR (qPCR), as described previously (40). Phage DNA was released by heat treatment for 10 min at 100°C. As Stx phages carry only one stx gene copy (GC), phage numbers were determined by qPCR assays targeting stx1 or stx2 genes. These were performed with a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche Diagnostics) as described by Derzelle et al. (41), with minor modifications as follows. The amplification reaction mixture contained 1× LightCycler 480 Probes Master mix (Roche Diagnostics), a 500 nM concentration of each primer (stx1B-for, stx1-rev, stx2-for, and stx2-rev), and a 200 nM concentration of each probe (stx1 and stx2 probes). Three microliters of extracted DNAs was used as the template in qPCR. The linearity and limit of quantification of the qPCR assay had formerly been determined by using calibrated suspensions of STEC corresponding to dilutions of pure cultures of stx1- and stx2-positive control strain EDL933 containing both stx1 and stx2 genes. The amplification efficiency (E) was calculated using the following equation: E = 10−1/s − 1, where s is the slope of the linear regression curve obtained by plotting the log genomic copy numbers of E. coli strains in the PCR against threshold cycle (CT) values. The CT value was defined as the PCR cycle at which the fluorescent signal exceeded the background level. The CT was determined automatically by the use of LightCycler 480 software with the second-derivative-maximum method, and the stx1 and stx2 gene copy (GC) numbers were calculated from the standard curve.

Evaluation of the infectious capacity of Stx phages.

To evaluate the ability of the Stx1 and Stx2 phages to infect E. coli, E. coli K-12 strain DH5α and 17 stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains were used as host strains. Each host strain was grown in LB at 37°C overnight with shaking. Two hundred microliters of each culture was added to 5 ml of molten LB top agarose and immediately poured onto LB-agar plates. Ten microliters of filtered supernatants containing Stx phages obtained after induction of six strains (H19, 5917/97, 3901/97, F46-223, 09QMA277.2, and 21765) was spotted onto plates containing the LB top agarose overlay and incubated overnight at 37°C.

Construction of lysogens.

E. coli K-12 strains (DH5α and MG1655) and stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains were grown overnight in LB broth at 37°C with shaking. For practical reasons, only a subset of five stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains (191.1, 5080/97, 318/98, 21474, and 21766) were used. One milliliter of host culture was mixed with 100, 250, or 500 μl (multiplicity of infection [MOI] between 0.1 and 0.5) of the different Stx phages such as Stx1 or Stx2 or a mix of Stx1 and Stx2 phage suspensions resulting from the mitomycin C induction of the H19 strain (phage ΦH19s), 5917/97 strain (phage Φ5917s), or 3901/97 strain (phage Φ3901m), respectively, and incubated 1 h at 37°C without shaking. The mixtures were then diluted 10-fold, plated onto LB-agar plates, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After incubation, colonies were enumerated and values were compared to the enumeration of the uninfected strains used as a control, to check whether a majority of the host cells had been lysed and thus infected upon contact with the phage. Finally, 5 to 10 colonies were purified and tested for lysogeny by PCR amplification of stx1 and stx2 genes (as described above) and of host-phage attL junction sites (19).

Propagation and purification of Stx phages and electron microscopy.

E. coli laboratory strain MG1655 was used as the host for purification and propagation of Stx1 and Stx2 phages in equal proportions obtained from strains H19, 2976-1, and 11368 and from strains 5917/97, 3901/97, and 21765(1), respectively (Table 1). Stx phage particles, obtained after induction, were amplified and purified in solid medium, as follows. Stx phages were isolated by the double-agar overlay plaque assay, as described above. One lysis plaque was removed with a sterile toothpick and resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM MgSO4 buffer. Two hundred microliters of an overnight culture of the host strain was mixed with 5 ml of molten LB top agarose, immediately poured onto LB-agar plates, and allowed to solidify. Fifty microliters of phage suspension was spotted onto these plates and incubated 8 h at 37°C. The spots were collected and resuspended in 100 μl of 10 mM MgSO4 buffer. Serial dilution of the lysates was then performed, and the diluted lysates were used in a new round of plaque assays and incubated 8 h at 37°C to produce confluent lysis of the host strain. Finally, 5 ml of 10 mM MgSO4 buffer was placed onto the top agar and incubated 8 h at 4°C and then recovered and filtered through low-protein-binding 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane filters (Millex-GP PES; Millipore).

The lysates (5 to 10 ml) were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 20,000 × g for 2 h in a swinging rotor (SW32Ti), and the pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of 10 mM MgSO4 buffer. They were tested for the presence of the stx gene by qPCR as described above. Five microliters of these suspensions was placed onto copper grids with carbon-coated Formvar films and subjected to negative-contrast analysis using 2% uranyl acetate dehydrate. Samples were examined using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi HT7700) (Elexience, France) at 80 kV. Microphotographs were acquired with an AMT charge-coupled-device camera.

RESULTS

Evaluation of Stx phage induction from clinical and dairy STEC O26:H11 isolates.

Fourteen STEC O26:H11 strains were used to measure the level of induction of their Stx phages occurring either spontaneously (i.e., in the absence of MMC) or with the addition of MMC. For all the strains tested, the OD600 was lower after 24 h of incubation with MMC (OD600, <1.25) than in the absence of MMC (OD600, >2) (Table 2). Such a low OD600 was an indicator of bacterial cell lysis and phage induction. qPCR tests and plaque assays were then performed to assess the amount of Stx phages produced by each strain in the presence and absence of the inducing agent.

TABLE 2.

Level of induction of Stx phage expressed in OD600 units

| Strain | OD600a |

|

|---|---|---|

| −MMC | +MMC | |

| 2976-1 | 3.50 ± 0.10 | 0.31 ± 0.09 |

| 10d | 3.33 ± 0.22 | 0.71 ± 0.17 |

| 09QMA277.2 | 3.10 ± 0.14 | 0.37 ± 0.08 |

| 09QMA245.2 | 3.20 ± 0.36 | 0.73 ± 0.11 |

| F46-223 | 3.25 ± 0.26 | 0.34 ± 0.14 |

| VTH7 | 2.73 ± 0.09 | 0.88 ± 0.04 |

| H19 | 2.80 ± 0.29 | 0.78 ± 0.04 |

| 3901/97 | 2.67 ± 0.33 | 0.68 ± 0.07 |

| 11368 | 2.75 ± 0.06 | 0.60 ± 0.11 |

| 3073/00 | 3.03 ± 0.38 | 0.45 ± 0.41 |

| 5917/97 | 2.86 ± 0.33 | 0.22 ± 0.05 |

| 29348 | 3.28 ± 0.22 | 0.25 ± 0.06 |

| 31132 | 2.98 ± 0.26 | 0.37 ± 0.09 |

| 21765(1) | 2.75 ± 0.17 | 1.23 ± 0.13 |

OD600 of untreated (−MMC) and MMC-treated (+MMC) STEC O26:H11 culture after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. The values are the means of the results of three independent experiments.

Stx phages could be detected by qPCR in all the STEC O26:H11 culture supernatants tested, indicating that all the strains were capable of producing Stx phages (Fig. 1). Levels of Stx phage production were highly variable between the strains (Fig. 1), and in most cases, the presence of MMC increased the phage particle yield. There was no significant difference in the basal induction level of Stx phages between the human and dairy strains, and the same was true in the presence of MMC (Fig. 1). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the induction rates of Stx phages according to their insertion sites, except for the spontaneous induction of Stx phages inserted into yecE, the rate of which was significantly higher than that of Stx phages integrated into wrbA (P < 0.05) or yehV (P < 0.01) as determined with a Fisher test (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Quantification of DNA from Stx1 and Stx2 phages. Quantification by qPCR of DNA of Stx1 and Stx2 phages extracted from supernatants obtained from untreated (−MMC; gray bars) or MMC-treated (+MMC; black bars) STEC O26:H11 cultures was performed. The STEC strains were from dairy (D) and human (H) origins, and their Stx phages were integrated into wrbA, yehV, yecE, or sbcB sites. The concentration of Stx phages was expressed in log10 values of stx gene copies per milliliter (log10 GC/ml). The data were obtained from three independent analyses, and the average copy numbers for each phage DNA are shown. Bars indicate standard deviations.

Production of Stx phages was observed under both conditions, i.e., in the presence and absence of MMC. In the absence of MMC, the level of Stx phage particles spontaneously produced ranged between 3.49 log10 and 7.67 log10 GC/ml (numbers of stx gene copies/ml) whereas when MMC was added, the Stx phage levels were between 3.47 log10 and 9.46 log10 GC/ml. Overall, the addition of MMC resulted in an average increase of 2 log10 GC relative to the levels seen with spontaneous induction (P < 0.05 [Fisher test]). Two exceptions were observed. For strain 3901/97, the levels of the Stx1 phage were not significantly different with and without MMC, suggesting that the Stx1 phage is a noninducible phage or that its induction pathway is distinct from the SOS response. For strain 09QMA277.2, which contains both Stx1 and Stx2 phages, production of the Stx1 phage became undetectable when MMC was added, suggesting that the production of Stx2 phage upon induction outcompetes that of the Stx1 phage. Additional work is required to support these hypotheses.

Comparing the production levels of Stx1 phages to those of Stx2 phages, a difference was observed (P < 0.001 [Fisher test]). This was true both in the presence and in the absence of MMC, since the amounts of Stx2 phages were 2.11 and 3.16 log10 greater, respectively, than those of Stx1 phages.

The Stx phage titers were then determined by enumeration of infectious Stx phages using the double-agar layer method and compared to the concentrations of Stx phage DNA determined by qPCR. Except for one strain (11368), all the strains generated infectious particles capable of producing plaques with the E. coli DH5α recipient strain. Four strains (2976-1, 09QMA245.2, VTH7, and 3073/00) also produced infectious Stx phages capable of promoting confluent lysis on plates, but these failed to generate visible and identifiable isolated plaques (Fig. 2). As observed with qPCR, the mean titers for Stx2 phages were higher by 2 log10 than those for Stx1 phages. However, the Stx phage titers determined by plaque enumeration were lower by an average of 1.98 log10 ± 1.01 (decreases of a minimum of 0.79 for strain 3901/97 and of a maximum of 4.28 log10 for strain H19) than the concentrations of Stx phage genomes determined by qPCR. Using E. coli MG1655 instead of DH5α as a recipient strain, the Stx phage titers obtained were similar or even lower (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Quantification of Stx1 and Stx2 phage particles. Quantification by enumeration of lysis plaques from particles of Stx1 and Stx2 phages obtained from supernatants derived from MMC-treated STEC O26:H11 cultures was performed. The STEC strains were from dairy (D) and human (H) origins, and their Stx phages were integrated into wrbA, yehV, yecE, or sbcB sites. The titer of the original phage preparation was expressed in PFU per milliliter (PFU/ml). The data were obtained from three independent analyses, and the average titers for each phage are shown. Bars indicate standard deviations.

Susceptibility of stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 to Stx phages and lysogenization.

Seventeen stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains and the E. coli K-12 DH5α strain were evaluated using spot agar tests for their sensitivity to six filtered supernatants containing Stx phages released after induction with MMC from strains H19, 5917/97, 3901/97, F46-223, 09QMA277.2, and 21765(1). The results obtained from the 102 different E. coli/Stx phage interactions tested are reported in Table 3. The 17 strains were not infected equally by Stx phages. One strain (64.36) was not sensitive to any of the six Stx phages, and two strains (09QMA04.2 and 09QMA355.2) were infected by only one Stx phage. In contrast, other strains such as 191.1, 5080/97, and 5021/97 were sensitive to all six of the Stx phages. Overall, 55 (54%) of the 102 E. coli/Stx phage interactions tested were positive for infection. A total of 68.7% of the human strains were sensitive to Stx phages, whereas only 40.7% of dairy strains were infected, a difference which was statistically significant (P = 0.008 [chi-square test]). In addition, the levels of turbidity of the lysis area differed among the strains tested (Table 3). Clear lysis was obtained with DH5α, in contrast to most of the stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains, which generated lysis areas that were more opaque.

TABLE 3.

Susceptibility of E. coli O26:H11 host strains to Stx phages obtained from STEC O26:H11

| Origina | Strain | Stx phage to which strain is susceptiblef |

Total no. of Stx phages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΦH19 | Φ5917 | Φ3901 | ΦF46-223 | Φ277.2 | Φ21765 | |||

| Dairy product | 09QMA04.2 | − | − | + | − | − | − | 1 |

| Dairy product | 09QMA315.2 | + | ++ | + | − | + | − | 4 |

| Dairy product | 09QMA306.D | − | + | − | − | + | − | 2 |

| Dairy product | FR14.18 | − | + | + | − | − | − | 2 |

| Dairy product | 4198.1 | − | − | + | ++ | ++ | + | 4 |

| Dairy product | 191.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Dairy product | 64.36 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 |

| Dairy product | 09QMA355.2 | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| Dairy product | F61-523 | − | + | − | − | ++ | − | 2 |

| Human (HUS) | 5021/97 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Human (HUS) | 5080/97 | + | + | +b | + | + | ++ | 6 |

| Human (HUS) | 318/98 | − | − | + | + | ++ | − | 3 |

| Human (HUS) | 21474 | − | +c | ++++d | +++ | ++ | +++ | 5 |

| Human (HUS) | 21766 | − | + | + | − | − | + | 3 |

| Human (NK) | MB04 | − | + | + | + | − | + | 4 |

| Human (NK) | MB01 | − | + | − | + | + | + | 4 |

| Human (HUS) | 29690 | − | + | ++ | − | − | − | 2 |

| K-12 | DH5αe | ++++c | ++++c | ++++ | ++++c | ++++c | +++ | 6 |

| Total | 18 | 5 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 9 | |

HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; NK, not known.

Presence of small lysis plaques instead of a confluent lysis area was detected.

Presence of a blurred halo around the lysis area was detected.

Clear lysis with colonies in the lysis plaque was seen.

The E. coli K-12 strain was used as a control strain.

−, nondetectable lysis in the spot area; ++++, clear lysis in the spot area; +++, minimally opaque lysis in the spot area; ++, moderately opaque lysis in the spot area; +, maximally opaque lysis in the spot area.

Phages Φ5917 and Φ3901m could infect 76.4% and 70.6% of stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 bacteria, respectively, while phages ΦF46-223, Φ277.2, and Φ21765 could infect between 47% and 59% of stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 bacteria. In contrast, phage ΦH19 infected only 23.5% of the stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains. These differences between the phages were not significant, however, except for phages Φ5917 and Φ3901m, whose infectivity was significantly higher than that of the phage ΦH19 (P = 0.006 and P = 0.016, respectively [chi-square test]). Finally, the E. coli K-12 DH5α strain used as a control was susceptible to infection with all the phages tested, showing marked lytic areas.

Attempts to lysogenize E. coli K-12 strains DH5α and MG1655 with filtered supernatants containing Stx phages were then performed. Suspensions of Stx1 phage (ΦH19) or of Stx2 phage (Φ5917) obtained from strain H19 or strain 5917/97, respectively, as well as a mixed suspension of both Stx1 and Stx2 phages (Φ3901m) obtained from 3901/97 strain were tested. A high decrease in DH5α bacterial viability, i.e., from −5.32 to −6.19 log10, respectively, was observed in the presence of phages Φ5917 and Φ3901m compared to the control conditions in the absence of phages, and similar results were observed with MG1655 (data not shown). In contrast, only a small decrease (<1.01 log10) in DH5α bacterial viability was observed using phage ΦH19. Lysogens could be obtained only with phage Φ3901m, with both strain DH5α and strain MG1655, and these acquired the Stx2 phage but not the Stx1 phage (data not shown). For these two E. coli lysogens, the left attachment (attL) bacterium/phage junction site could be amplified by PCR at the yecE site (data not shown), suggesting that the Stx2 phage integrated its genome into the yecE bacterial chromosomal gene.

When the same lysogenization assays were conducted with four stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains (318/98, 191.1, 5080/97, and 21766), the presence of Stx phages did not decrease viability of the recipient strains and no lysogens could be recovered, in contrast to DH5α used as a positive control (data not shown). This suggested to us some level of resistance to infection in liquid, although growth occurred in top agar, as turbid plaques were obtained (see above). To test whether phage resistance was due to restriction or modification, Stx2 phage Φ3901 was propagated onto a fifth recipient stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strain (21474). Using this new stock for a lysogenization assay performed on strain 21474, no lysogens could be isolated either. However, after the step of adsorption of phage Φ3901 onto the 21474 strain, the mixture was positive for PCR amplification of the attL junction at the yecE site, suggesting that lysogenic bacterial cells were present (data not shown).

Electron microscopy.

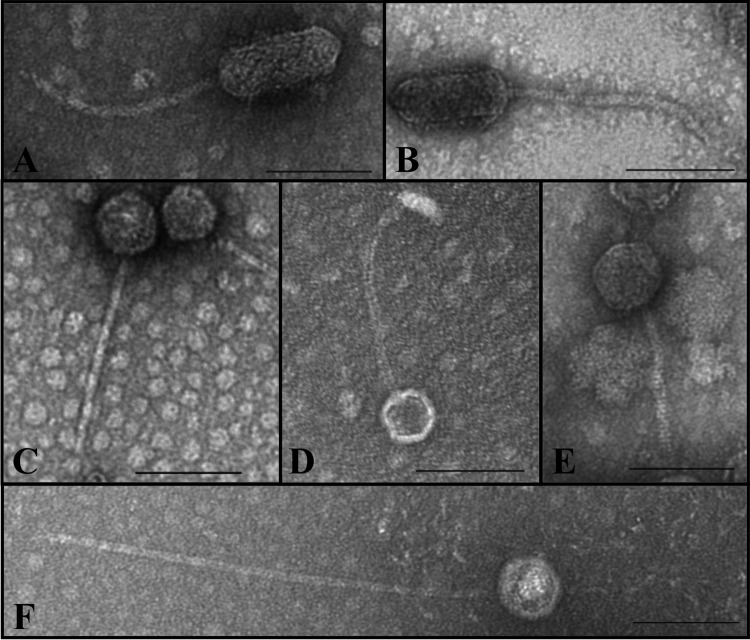

Six Stx phages, including three Stx1 phages (ΦH19, Φ2976-1, and Φ11368) and three Stx2 phages (Φ5917, Φ3901, and Φ21765), were subjected to plaque purification from STEC O26:H11 and amplified on the MG1655 K-12 strain, which is devoid of functional prophages (see Materials and Methods). Using observation by transmission electron microscopy, three different kinds of phages were identified (Fig. 3). Two phages (Φ3901 and ΦH19) presented an elongated (prolate) capsid measuring 42 to 52 nm in width and 106 to 121 nm in length, with a long flexible tail of ca. 190 to 209 nm, and were members of the Siphoviridae family (Fig. 3A and B). Three phages (Φ11368, Φ5917, and Φ21765) showed also a morphology of Siphoviridae, with an isometric head of ca. 44-nm to 64-nm diameter and a long tail ca. 150 to 195 nm in length (Fig. 3C, D, and E). Finally, phage Φ2976-1 was also a member of the Siphoviridae family, with an isometric head of ca. 56-nm diameter and a very long tail ca. 411 nm in length (Fig. 3F).

FIG 3.

Electron micrographs of Stx phage particles obtained from STEC O26:H11. Electron micrographs depict the following six phages: (A) phage Φ3901; (B) phage ΦH19; (C) phage Φ11368; (D) phage Φ5917; (E) phage Φ21765; (F) phage Φ2976-1. (A and B) Stx phage particles with an elongated head and a long flexible tail. (C to E) Siphoviridae phages with a long tail. (F) Siphoviridae phage with a very long tail. Bars, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

All of the 14 (100%) STEC O26:H11 strains examined here contained inducible Stx phages and were capable of producing Stx phages both spontaneously and in the presence of MMC. Other studies showed that 18% to 89% of STEC bacteria isolated from cattle or wastewaters and belonging to a wide variety of serotypes contained inducible Stx2 phages (26, 38).

According to previous work, the concentrations of phage DNA obtained after induction are inversely proportional to the optical densities of the culture (26). This was also the case here, although several exceptions were observed. For example, strains 31132 and 21765(1) showed the same Stx2 phage concentrations of ca. 9 log10 GC/ml but distinct OD600 values of 0.37 and 1.23, respectively. Conversely, strains VTH7 and H19 displayed similar OD600 values (i.e., 0.88 and 0.78, respectively), but H19 produced a hundred times more Stx1 phage than VTH7. Although OD600 values still represent a good indicator of qualitative Stx phage induction, the use of alternative assays such as qPCR seems therefore preferable for a more accurate and quantitative assessment of Stx phage induction.

The addition of MMC resulted in Stx phage induction levels 2 log10 higher than those obtained under spontaneous conditions, and a higher level of induction was observed for Stx2 phages than for Stx1 phages. This less-pronounced effect of MMC on Stx1 production was also observed by Ritchie et al. (42). Moreover, it had been shown previously that spontaneous induction of Stx1 phages could be increased significantly when STEC were grown in a low-iron medium (43), although no correlation between induction levels obtained in low-iron medium and in the presence of MMC was observed for various Stx1 phages (42). Finally, although the levels of Stx phages evaluated here were highly variable, there was no significant difference between the human and the dairy strains in the Stx phage induction levels in the presence and absence of MMC. As there is a direct relationship between Stx phage induction and toxin production (26), this result would therefore indicate that isolates from dairy strains are capable of producing Stx at levels comparable to those seen with human isolates. Similarly, no differences were observed according to the Stx phage insertion sites, except for spontaneous induction, which was higher for Stx phages inserted into yecE than for those inserted into wrbA and yehV. Interestingly, strains with Stx2 phage integrated into yecE were described previously as highly virulent (19).

Most of the STEC O26:H11 strains generated infectious Stx phage particles capable of producing plaques with the E. coli DH5α recipient strain. Nevertheless, as a few Stx phages were unable to generate isolated plaques, improvements of the plaque assay used here could be considered in the future, as described by Islam et al. (44). In addition, the phage titers determined by plaque enumeration were lower than the concentrations of phage genomes determined by qPCR, as reported previously (45). Several factors have been proposed to influence plaque enumeration, including the susceptibility of the host strain and the presence of noninfectious particles in the phage suspension tested (45, 46). Nevertheless, despite this difference, the relative levels of Stx1 and Stx2 phages determined by the two methods among the panel of STEC O26:H11 strains were in agreement.

Considering the susceptibility of stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains to a subset of six Stx phages from STEC O26:H11, a large variability in sensitivity was observed, as one strain (64.36) was not infected by any of the six Stx phages tested whereas, in contrast, three strains (191.1, 5080/97, and 5021/97) were sensitive to all of the Stx phages. This phenomenon was previously observed by Muniesa et al. when E. coli strains of various serotypes were tested as recipients (47). Indeed, E. coli O26 strains 216 and 224 were infected by 1 and 7 of 11 Stx phages tested, respectively (47). Interestingly, the sensitivity of the human strains to Stx phages here was higher than that observed with the dairy strains. It is tempting to speculate that the clinical strains were modified by passage through humans and became more susceptible to Stx phages. However, a more extensive comparison with a higher number of human and dairy strains is required to confirm these findings.

Investigating lysogenic conversion by Stx phages using E. coli DH5α and MG1655 as recipient strains, lysogenic stx-positive isolates could be obtained, with Stx2 prophages inserted into yecE. However, all our attempts to lysogenize stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains failed. Difficulties in the production of lysogens and variability in transduction effectiveness have already been reported for Stx phages. Muniesa et al. obtained stable lysogens with only 6 of 30 Stx phages derived from cattle STEC strains (26). Bielaszewska et al. also reported that lysogenization of clinical E. coli O26:H11 was not systematic, since only two or three of six stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains could be lysogenized by Stx2 phages, with rates of lysogenization ranging from 1 × 10−7 to 6 × 10−6 per recipient cell, i.e., 10× lower than that obtained with E. coli laboratory strain C600. More importantly, transfer of Stx1 phages was even less successful since, in the same study, only one of four Stx1 phages lysogenized E. coli O26:H11, and this was true for only one of the six stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strains tested (27).

The stx-negative E. coli strains used as recipients in our study contained vacant Stx phage insertion sites (19), indicating that the lack of a free insertion site was not the reason for the failure to obtain lysogens with E. coli O26:H11. Interestingly, chromosomal insertion of Stx phage genome into a fraction of bacterial cells from an stx-negative E. coli O26:H11 strain (21474) suspension could be demonstrated here by PCR amplification of an attL junction at the yecE site, suggesting that Stx phages have the ability to lysogenize stx-negative E. coli O26:H11, presumably with a low frequency that did not allow the isolation of lysogens in the absence of selective pressure. Alternatively, Stx prophage instability might also prevent the isolation of lysogens. Indeed, although lysogenization of stx-negative E. coli strains such as enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC or EAggEC) strains with Stx phages was shown previously (27, 48, 49), stable Stx phage acquisition was also observed to rarely occur (27, 49). Despite the fact that our results are in agreement with the difficulties of lysogenization observed by others, it should be noted that an MOI higher than those used here might have increased the rate of lysogen production.

Finally, Stx phages from STEC O26:H11 showed some variability in their morphology since three distinct shapes were observed by electron microscopy among six Stx phages analyzed. The two phages Φ3901 (Stx1) and ΦH19 (Stx2) displayed an elongated (prolate) capsid and a long flexible tail, as described previously in the case of phage ΦH19 (50). This result indicates that phages with genomes harboring either an stx2 or an stx1 gene can share similar shapes, as previously observed by Muniesa et al. (51). The second phage morphology observed here was characterized by isometric head and was shared by an Stx1 phage (Φ11368) and two Stx2 phages (Φ5917/97 and Φ21765). Such a morphology has been previously observed for two Stx2 phages, ΦSW13 and ΦSW16 (26, 47). Finally, the third type of phage morphology was found for phage Φ2976-1, which possessed a very long tail of about 411 nm. Such a long tail has already been observed by Hoyles et al. for virus-like particles that corresponded to bacteriophages and were associated with human fecal or cecal samples (52). Taken together, these results are consistent with previous reports showing that there was no relationship between the presence of a particular stx variant and the morphology of the corresponding phage (38). This also confirmed the diversity of phage morphologies circulating in the STEC population, and in STEC O26:H11 strains in particular.

In conclusion, Stx1 and Stx2 phages of STEC O26:H11 are characterized by high diversity, with variations observed in their induction levels, morphologies, and abilities to infect E. coli strains. Interestingly, we noted that the lysogenization of stx-negative E. coli with Stx phages was a rare event and that more appropriate conditions were required for successful isolation of stable lysogens. Nevertheless, lysogenization of AEEC O26:H11, although at a low frequency, seems possible, and such an event would convert them into STEC strains potentially harmful for humans. Molecular methods such as qPCR could represent alternative assays to identify and quantify lysogens within an E. coli population infected by Stx phages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Patricia Mariani-Kurkdjian for supplying STEC O26:H11 human strains. We thank Nadine Belin and Emeline Cherchame for technical assistance. This work has benefited from the facilities and expertise of MIMA2 MET (UMR 1313 GABI, INRA, Equipe Plateformes, Jouy-en-Josas, France). We also thank the French National Reference Laboratory and associated NRC teams for E. coli for isolation of all field strains studied.

Funding Statement

Ministere de l'Agriculture (France) provided funding to Ludivine Bonanno, Valerie Michel, and Frederic Auvray under grant ARMADA. Centre National Interprofessionnel de l'Economie Laitiere (CNIEL) provided funding to Ludivine Bonanno, Valerie Michel, and Frederic Auvray under grant “O26-EHEC-like.” Association Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie (ANRT) provided funding to Ludivine Bonanno under grant number 2012/0975.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karmali MA, Steele BT, Petric M, Lim C. 1983. Sporadic cases of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome associated with faecal cytotoxin and cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in stools. Lancet i:619–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. 2005. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 365:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EFSA. 2014. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2012. EFSA J 12:3547 http://www.efsa.europa.eu/fr/efsajournal/pub/3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerhackl LB, Rosales A, Hofer J, Riedl M, Jungraithmayr T, Mellmann A, Bielaszewska M, Karch H. 2010. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26:H11-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: bacteriology and clinical presentation. Semin Thromb Hemost 36:586–593. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King L, Gouali M, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Vaillant V; le réseau des néphrologues pédiatres . 2013. Surveillance du syndrome hémolytique et urémique post-diarrhéique chez les enfants de moins de 15 ans en France en 2013. IVS, Saint-Maurice, France. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks JT, Sowers EG, Wells JG, Greene KD, Griffin PM, Hoekstra RM, Strockbine NA. 2005. Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983–2002. J Infect Dis 192:1422–1429. doi: 10.1086/466536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrokh C, Jordan K, Auvray F, Glass K, Oppegaard H, Raynaud S, Thevenot D, Condron R, De Reu K, Govaris A, Heggum K, Heyndrickx M, Hummerjohann J, Lindsay D, Miszczycha S, Moussiegt S, Verstraete K, Cerf O. 15 March 2013. Review of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and their significance in dairy production. Int J Food Microbiol doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussein HS, Sakuma T. 2005. Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in dairy cattle and their products. J Dairy Sci 88:450–465. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy M, Carroll A, Whyte P, O'Mahony M, Anderson W, McNamara E, Fanning S. 2005. Prevalence and characterization of Escherichia coli O26 and O111 in retail minced beef in Ireland. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2:357–360. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2005.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espié E, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Grimont F, Pithier N, Vaillant V, Francart S, de Walk H, Vernozy-Rozand C. 2006. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26 infection and unpasteurised cows cheese, France 2005. Abstr 6th Int Symp Shiga Toxin (Verocytoxin)-Producing Escherichia coli Infect, Melbourne, Australia, 2006. http://opac.invs.sante.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=7011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ethelberg S, Smith B, Torpdahl M, Lisby M, Boel J, Jensen T, Molbak K. 2007. An outbreak of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O26:H11 caused by beef sausage, Denmark 2007. Euro Surveill 12:E070531.4 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith HW, Green P, Parsell Z. 1983. Vero cell toxins in Escherichia coli and related bacteria: transfer by phage and conjugation and toxic action in laboratory animals, chickens and pigs. J Gen Microbiol 129:3121–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt H. 2001. Shiga-toxin-converting bacteriophages. Res Microbiol 152:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien AD, Newland JW, Miller SF, Holmes RK, Smith HW, Formal SB. 1984. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science 226:694–696. doi: 10.1126/science.6387911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheutz F, Teel LD, Beutin L, Pierard D, Buvens G, Karch H, Mellmann A, Caprioli A, Tozzoli R, Morabito S, Strockbine NA, Melton-Celsa AR, Sanchez M, Persson S, O'Brien AD. 2012. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J Clin Microbiol 50:2951–2963. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00860-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerlin P, McEwen SA, Boerlin-Petzold F, Wilson JB, Johnson RP, Gyles CL. 1999. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J Clin Microbiol 37:497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang WL, Bielaszewska M, Liesegang A, Tschape H, Schmidt H, Bitzan M, Karch H. 2000. Molecular characteristics and epidemiological significance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26 strains. J Clin Microbiol 38:2134–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delannoy S, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Bonacorsi S, Liguori S, Fach P. 26 November 2014. Characteristics of emerging human-pathogenic Escherichia coli O26:H11 isolated in France between 2010 and 2013 and carrying the stx2d gene only. J Clin Microbiol 53:486–492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02290-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonanno L, Loukiadis E, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Oswald E, Garnier L, Michel V, Auvray F. 2015. Diversity of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O26:H11 strains examined via stx subtypes and insertion sites of Stx and EspK bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3712–3721. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00077-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold S, Karch H, Schmidt H. 2004. Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages—genomes in motion. Int J Med Microbiol 294:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimmitt PT, Harwood CR, Barer MR. 2000. Toxin gene expression by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: the role of antibiotics and the bacterial SOS response. Emerg Infect Dis 6:458–465. doi: 10.3201/eid0605.000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler B, Karch H, Schmidt H. 2000. Antibacterials that are used as growth promoters in animal husbandry can affect the release of Shiga-toxin-2-converting bacteriophages and Shiga toxin 2 from Escherichia coli strains. Microbiology 146(Pt 5):1085–1090. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-5-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little JW, Mount DW. 1982. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aksenov SV. 1999. Dynamics of the inducing signal for the SOS regulatory system in Escherichia coli after ultraviolet irradiation. Math Biosci 157:269–286. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(98)10086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aertsen A, Faster D, Michiels CW. 2005. Induction of Shiga toxin-converting prophage in Escherichia coli by high hydrostatic pressure. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1155–1162. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1155-1162.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muniesa M, Blanco JE, De Simon M, Serra-Moreno R, Blanch AR, Jofre J. 2004. Diversity of stx2 converting bacteriophages induced from Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from cattle. Microbiology 150:2959–2971. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bielaszewska M, Prager R, Kock R, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Tschape H, Tarr PI, Karch H. 2007. Shiga toxin gene loss and transfer in vitro and in vivo during enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26 infection in humans. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:3144–3150. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02937-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karch H, Meyer T, Russmann H, Heesemann J. 1992. Frequent loss of Shiga-like toxin genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli upon subcultivation. Infect Immun 60:3464–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acheson DW, Reidl J, Zhang X, Keusch GT, Mekalanos JJ, Waldor MK. 1998. In vivo transduction with Shiga toxin 1-encoding phage. Infect Immun 66:4496–4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Kock R, Fruth A, Bauwens A, Peters G, Karch H. 2011. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 11:671–676. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muniesa M, Hammerl JA, Hertwig S, Appel B, Brussow H. 2012. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4: a new challenge for microbiology. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4065–4073. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00217-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imamovic L, Jofre J, Schmidt H, Serra-Moreno R, Muniesa M. 2009. Phage-mediated Shiga toxin 2 gene transfer in food and water. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1764–1768. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02273-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madic J, de Garam CP, Brugere H, Loukiadis E, Fach P, Jamet E, Auvray F. 2011. Duplex real-time PCR detection of type III effector tccP and tccP2 genes in pathogenic Escherichia coli and prevalence in raw milk cheeses. Lett Appl Microbiol 52:538–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loukiadis E, Callon H, Mazuy-Cruchaudet C, Vallet V, Bidaud C, Ferre F, Giuliani L, Bouteiller L, Pihier N, Danan C. 2012. Surveillance des E. coli producteurs de shigatoxines (STEC) dans les denrées alimentaires en France (2005–2011). Bull Epidemiol Hebd (Paris) 55:3–9. https://pro.anses.fr/bulletin-epidemiologique/Documents//BEP-mg-BE55.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevisani M, Mancusi R, Delle Donne G, Bacci C, Bassi L, Bonardi S. 2014. Detection of Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in bovine dairy herds in Northern Italy. Int J Food Microbiol 184:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Imamovic L, Muniesa M. 2011. Quantification and evaluation of infectivity of Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages in beef and salad. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:3536–3540. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loś JM, Loś M, Wegrzyn G, Wegrzyn A. 2009. Differential efficiency of induction of various lambdoid prophages responsible for production of Shiga toxins in response to different induction agents. Microb Pathog 47:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García-Aljaro C, Muniesa M, Jofre J, Blanch AR. 2009. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity among induced, stx2-carrying bacteriophages from environmental Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:329–336. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01367-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kropinski AM, Mazzocco A, Waddell TE, Lingohr E, Johnson RP. 2009. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. Methods Mol Biol 501:69–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-164-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madic J, Peytavin de Garam C, Vingadassalon N, Oswald E, Fach P, Jamet E, Auvray F. 2010. Simplex and multiplex real-time PCR assays for the detection of flagellar (H-antigen) fliC alleles and intimin (eae) variants associated with enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serotypes O26:H11, O103:H2, O111:H8, O145:H28 and O157:H7. J Appl Microbiol 109:1696–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derzelle S, Grine A, Madic J, de Garam CP, Vingadassalon N, Dilasser F, Jamet E, Auvray F. 2011. A quantitative PCR assay for the detection and quantification of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in minced beef and dairy products. Int J Food Microbiol 151:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritchie JM, Wagner PL, Acheson DW, Waldor MK. 2003. Comparison of Shiga toxin production by hemolytic-uremic syndrome-associated and bovine-associated Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:1059–1066. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.1059-1066.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner PL, Livny J, Neely MN, Acheson DW, Friedman DI, Waldor MK. 2002. Bacteriophage control of Shiga toxin 1 production and release by Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 44:957–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Islam MR, Ogura Y, Asadulghani M, Ooka T, Murase K, Gotoh Y, Hayashi T. 2012. A sensitive and simple plaque formation method for the Stx2 phage of Escherichia coli O157:H7, which does not form plaques in the standard plating procedure. Plasmid 67:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Imamovic L, Serra-Moreno R, Jofre J, Muniesa M. 2010. Quantification of Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophages, by real-time PCR and correlation with phage infectivity. J Appl Microbiol 108:1105–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loś JM, Golec P, Wegrzyn G, Wegrzyn A, Loś M. 2008. Simple method for plating Escherichia coli bacteriophages forming very small plaques or no plaques under standard conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muniesa M, Serra-Moreno R, Jofre J. 2004. Free Shiga toxin bacteriophages isolated from sewage showed diversity although the stx genes appeared conserved. Environ Microbiol 6:716–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmidt H, Bielaszewska M, Karch H. 1999. Transduction of enteric Escherichia coli isolates with a derivative of Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophage ϕ3538 isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:3855–3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tozzoli R, Grande L, Michelacci V, Ranieri P, Maugliani A, Caprioli A, Morabito S. 2014. Shiga toxin-converting phages and the emergence of new pathogenic Escherichia coli: a world in motion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neely MN, Friedman DI. 1998. Functional and genetic analysis of regulatory regions of coliphage H-19B: location of Shiga-like toxin and lysis genes suggest a role for phage functions in toxin release. Mol Microbiol 28:1255–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muniesa M, de Simon M, Prats G, Ferrer D, Panella H, Jofre J. 2003. Shiga toxin 2-converting bacteriophages associated with clonal variability in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains of human origin isolated from a single outbreak. Infect Immun 71:4554–4562. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4554-4562.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Neve H, Gibson GR, Sanderson JD, Heller KJ, van Sinderen D. 2014. Characterization of virus-like particles associated with the human faecal and caecal microbiota. Res Microbiol 165:803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]