Abstract

Soil salinization is a growing threat to global agriculture and carbon sequestration, but to date it remains unclear how microbial processes will respond. We studied the acute response to salt exposure of a range of anabolic and catabolic microbial processes, including bacterial (leucine incorporation) and fungal (acetate incorporation into ergosterol) growth rates, respiration, and gross N mineralization and nitrification rates. To distinguish effects of specific ions from those of overall ionic strength, we compared the addition of four salts frequently associated with soil salinization (NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4) to a nonsaline soil. To compare the tolerance of different microbial processes to salt and to interrelate the toxicity of different salts, concentration-response relationships were established. Growth-based measurements revealed that fungi were more resistant to salt exposure than bacteria. Effects by salt on C and N mineralization were indistinguishable, and in contrast to previous studies, nitrification was not found to be more sensitive to salt exposure than other microbial processes. The ion-specific toxicity of certain salts could be observed only for respiration, which was less inhibited by salts containing SO42− than Cl− salts, in contrast to the microbial growth assessments. This suggested that the inhibition of microbial growth was explained solely by total ionic strength, while ion-specific toxicity also should be considered for effects on microbial decomposition. This difference resulted in an apparent reduction of microbial growth efficiency in response to exposure to SO42− salts but not to Cl− salts; no evidence was found to distinguish K+ and Na+ salts.

INTRODUCTION

Soil salinization affects a large area of land globally and has become a major threat to agricultural productivity and food security (1). Due to the wide distribution of salt-affected soils around the world (2, 3), it is important to understand the influence of salinity on the soil microbial community. The soil microbial decomposer community plays an essential role in the decomposition and stabilization of soil organic matter (SOM), as well as the cycling of nutrients vital for plant growth. How substrate during decomposition is allocated to either microbial biomass production or respiration determines the microbial growth efficiency (MGE), which is an important parameter for the C sequestration potential of a soil (4). The potential for soil C storage could be compromised by disturbances or unfavorable environmental conditions that reduce microbial growth efficiencies due to the metabolic burden they place on microbial cells (5).

It is generally held that fungus-dominated communities have a higher MGE than communities dominated by bacteria (4). Thus, changes in the relative contribution of bacteria and fungi to the soil microbial community are thought to reflect changes in ecosystem processes, such as decomposition, C sequestration potential, and nutrient cycling (6, 7). It is unclear whether fungi and bacteria are affected by salt exposure to a similar degree or if there are differences in salt sensitivity between these two major decomposer groups. It has been shown that fungi are more resistant to osmotic pressure, illustrated by their higher tolerance to high concentrations of low-molecular-weight organic compounds (8, 9). In addition, fungi also have been found to be more resistant to low water potentials brought about by decreasing soil moisture than most bacteria (10, 11). In soils exposed to salinity, both higher (12, 13) and lower (14–17) levels of contribution of fungi to the microbial community have been observed.

Often the influence of soil salinity on the soil microbial community has been studied using total microbial biomass measurements. However, the connection between the total microbial biomass and microbial contribution to soil processes is tenuous at best (6, 18, 19), rendering biomass a poor predictor for process rates carried out by the microbial community. Instead, responses in processes carried out by the active and growing part of the microbial community can be employed to detect inhibition by exposure to salts. For instance, salt additions have been found to influence and reduce microbial activity, measured as respiration (12, 20–23) or N transformation rates (22, 24). To date, there is a lack of comparative studies on the degree of sensitivity of a comprehensive range of different microbial processes. Processes showing differential sensitivity to salinity could have implications for soil biogeochemical cycles and the ecology of microorganisms, as well as the identification of informative endpoints for toxicity assessments. In addition, not all salts associated with soil salinization have the same effect on the microbial community. Differences in toxicity have been found between, e.g., SO42− and Cl− salts (25–30) as well as K+ and Na+ salts (28). However, few studies have been designed to explicitly compare the toxicity of different salts using a range of processes.

The aim of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis of the sensitivity of a range of different microbial processes to short-term salt exposure in a nonsaline soil. In the first part of the study, soil was exposed to a range of NaCl concentrations. The acute growth responses of bacteria and fungi were compared to assess differences in their tolerance to salinity. In addition, growth processes were compared to catabolic processes, including C and N mineralization and nitrification, to investigate the potential for salts to induce a shift in SOM dynamics and nutrient cycling. Considering the predicted higher tolerance of fungi to osmotic pressure, we hypothesized that fungal growth would show a higher tolerance to salts associated with soil salinization than bacterial growth. Further, we predicted that, as a symptom of the cost of physiological measures to cope with high osmotic potentials, microorganisms allocate substrate away from biomass production toward maintenance functions, leading to a situation where catabolic processes would be less inhibited by salt exposure than anabolic or growth-related processes. Incubation times were kept short to ensure that the measured responses are direct responses to salt exposure rather than inhibition confounded by the recovery due to a shift toward a more tolerant community. In the second part of the study, we conducted a comparative assessment of the toxicity of salts common in saline soils (NaCl, KCl, K2SO4, and Na2SO4) on respiration as well as fungal and bacterial growth. We hypothesized that Cl− salts would be more toxic than SO42− salts, and that Na+ salts would be more toxic than K+ salts. We also predicted that irrespective of the type of salt used, fungi would be more resistant than bacteria and respiration less inhibited than growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil sampling and characterization.

Soil was collected from a grassland site situated in Vomb, southern Sweden (55°40′27″N, 13°32′45″E). The soil is a well-drained sandy grassland soil. Multiple soil samples were collected with a spade from pits dug to a depth of ca. 20 cm and combined into composite samples, homogenized, and sieved (<2.8 mm). Samples were collected at several time points from the same site: September 2013, October 2013, November 2014, and December 2014.

Following sieving and homogenization, the water content of the soil was determined gravimetrically (105°C for 24 h), and the organic matter (OM) content was measured as loss on ignition (600°C for 10 h). Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH measurements were conducted in a 1:5 soil-water suspension. To measure NH4+ and NO3− concentrations, diffusion traps were placed in a KCl soil extract. The total microbial biomass was determined using substrate-induced respiration (SIR) (31) by adding 6 mg of glucose per g soil. After 2 h of incubation, CO2 was measured using a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a methanizer and a flame ionization detector. The measured respiration rate was converted to microbial biomass C using the relationship that 1 mg CO2 h−1 corresponds to 20 mg biomass-C (31). These SIR estimates of microbial biomass matched previous assessments of biomass from the same soils (data not shown).

Fungal biomass C was estimated by extracting and quantifying the amount of ergosterol in the soil sample. We assumed a fungal ergosterol content of 5 mg g−1 fungal biomass and a fungal C content of 45% (32, 33). Bacterial biomass C was estimated using a mass balance of fungal biomass C to total microbial biomass C.

Soil samples subsequently were stored in gas-permeable polyethylene bags at 4°C until further analysis. Before the start of the experiment, soil was kept at 22°C for 2 days. The study was divided into two parts, referred to as experiments 1 and 2 below.

Experiment 1.

In the first part of the study, the sensitivities of bacterial and fungal growth, respiration, and gross N mineralization and nitrification rates to sodium chloride (NaCl) were determined. Bacterial growth measurements were repeated in samples from all four sampling time points, fungal growth and respiration were measured in samples collected in September 2013 and December 2014, and gross N mineralization and nitrification rates were measured in the sample collected in October 2013. Before measuring microbial growth and process rates, NaCl was added to the soils in 8 to 12 different concentrations, which covered a range from 0 to 3,600 μmol NaCl per g soil in a series of 3-fold dilution steps, together with 100 μl distilled water per g soil. The salt additions resulted in a range of EC1:5 values from 0.06 to 65.6 dS m−1 (i.e., ca. 0.6 to 700 dS m−1 in a saturated soil paste [ECe] [21]). Generally, a soil is described as saline if the ECe is higher than 4 dS m−1, but studies of saline soils frequently include soils with a more than 10-fold higher ECe (23). Following the addition of NaCl, soils were incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h before microbial variables were determined.

Experiment 2.

In the second part of the study, we compared the toxic effects of salts common in saline soils, namely, NaCl, potassium chloride (KCl), potassium sulfate (K2SO4), and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), on bacterial growth, fungal growth, and respiration rates (described below). For each salt the same molar concentrations were used (0, 0.06, 0.17, 0.52, 1.6, 4.7, 14.1, 42.3, 127, 380, 1,140, and 3,420 μmol salt per g soil). The resulting electrical conductivity in the soil-salt combinations was measured in a 1:5 soil-water suspension and covered a range of EC1:5 values from 0.01 dS m−1 to 75 dS m−1. Changes in soil pH following salt additions were small (from pH 6.4 to around 6.1 in the treatment receiving the highest-concentration salt addition). Measurements were repeated on fresh samples from the same soil to verify reproducibility. Bacterial growth measurements were repeated in three independent experiments, while fungal growth and respiration measurements were repeated in two independent experiments.

Bacterial and fungal growth.

The bacterial growth rate was estimated by measuring the incorporation of 3H-labeled leucine (Leu) into bacteria extracted from soil according to references 34 and 35. Two grams of soil was mixed with 20 ml of water, followed by a 10-min centrifugation step at 1,000 × g. From the resulting bacterial suspension a 1.5-ml subsample was used to measure bacterial growth. Two microliters of [3H]Leu (37 MBq ml−1 and 5.74 TBq mmol−1; PerkinElmer, United Kingdom) was added to the suspension together with nonlabeled Leu, resulting in a final concentration of 275 nM Leu. After 2 h of incubation at 22°C in the dark, bacterial growth was terminated by the addition of 100% trichloroacetic acid. After a series of washing steps (34), the amount of incorporated radioactive label was measured using liquid scintillation. To assess whether salt toxicity to bacterial growth rates could be underestimated by measuring bacterial growth in a 20-ml soil suspension, we varied the amount of water added to create the soil suspension (5, 10, 15, and 20 ml). When the salt concentration was considered on a per-gram-of-soil basis, the different dilutions associated with the homogenization/centrifugation step had no influence on the dose-response relationship (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Since the volume of water added to the soil had no influence on the salt toxicity estimate (see Fig. S1), the estimated bacterial response was to the salt concentration in the soil, prior to water addition, rather than the concentration of salt in the bacterial suspension created.

Fungal growth was determined by measuring the incorporation of acetate (Ac) into ergosterol (32). One gram of soil was transferred into glass tubes to which a mixture of 20 μl [1-14C]acetic acid (Na+ salt; 2.04 GBq mmol−1, 7.4 MBq ml−1; PerkinElmer, United Kingdom) and unlabeled acetate was added together with 1.95 ml distilled water, resulting in a final acetate concentration of 220 μM. Samples then were incubated for 4 h at 22°C in the dark, after which growth was terminated with the addition of 1 ml 5% formalin. Ergosterol then was extracted, separated, and quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography and a UV detector (282 nm) and collected in a fraction collector (36). The radioactivity incorporated into the ergosterol fraction was measured using liquid scintillation.

Soil respiration.

Basal soil respiration was measured by transferring 2 g of soil into a 20-ml vial and purging the headspace with pressurized air. After purging, the vials were closed with crimp seals and incubated in the dark for approximately 16 h at 22°C. The CO2 concentration in the headspace then was analyzed using a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a methanizer and a flame ionization detector, and background levels of CO2 in pressurized air were subtracted.

Nitrogen transformation rates.

Gross N mineralization and nitrification rates were determined using the 15N pool dilution/enrichment technique (37). Ten grams of soil was transferred to microcosms and mixed with 300 μl of NH4Cl containing 0.24 g N liter−1 (16% 15N). One set of soil samples was extracted with 50 ml 1 M KCl within a few minutes after the addition of the 15NH4+ label and a second set after an incubation period of 24 h at room temperature. The extract was filtered through a Whatman GF/F filter, and the concentrations of 14NH4+-N, 15NH4+-N, 14NO3−-N, and 15NO3−-N in the filtrate were determined according to standard procedures using acidified diffusion traps containing a filter disc (37). The amounts of 15N/14N in the filter discs were measured at the stable isotope facility at the Department of Biology, Lund University, using a Flash 2000 elemental analyzer connected to a Delta V plus isotope-ratio mass spectrometer via the ConFlow IV interface (Thermo Scientific Inc., Bremen, Germany).

Duration of toxic effect.

Since the different endpoints chosen typically are measured using different time frames, we also included assessments for the duration of toxic effect by the added salts. For bacterial growth and fungal growth, we covered a range of 2 h to 96 h after salt addition, and for the effects on mineralization (respiration), we covered a range of 6 h to 96 h.

Calculations and data analysis.

In order to analyze the sensitivity of different microbial processes to salts, dose-response relationships were determined. To do this, values measured at different levels of salt addition first were normalized by dividing them by the average of the values measured in the samples that received no or low levels of salts and where no inhibition in process was observed. Normalized values then would fall in a range between 1 (no inhibition of process) and 0 (complete inhibition of process). Values obtained in repeated runs of the experiment were combined to generate a single curve. Log(IC50) values (the logarithm of the salt concentration resulting in 50% inhibition of the process rate) were estimated using the logistic model y = c/[1 + eb(x − a)], where y is the relative normalized process rate, x is the logarithm of the salt concentration, a is the value of log(IC50), b is a fitted parameter (slope) indicating the inhibition rate, and c is the process rate measured in the control without added salts (38). Kaleidagraph 4.5.0 for Mac (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) was used to fit inhibition curves using this equation. To compare toxicity, 95% confidence intervals were estimated for the log(IC50) values based on the logistic model. Our criterion for significant differences was nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals. This is a conservative criterion, as nonoverlapping 85% confidence intervals correspond to an α of 0.05 (39) to determine statistical significance.

Gross N mineralization and nitrification rates were estimated by the 15N pool dilution/enrichment technique (40–43) using the equations in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Soil characteristics.

The studied soil had a pH of 6.4 and an electrical conductivity of 0.09 dS m−1 (Table 1), classifying it as a nonsaline soil. The SOM content was 19 mg C g−1, the NH4+ content was 3.26 μg N g−1, and the NO3− content was 6.34 μg N g−1 (Table 1). The total amount of microbial biomass in the soil was 137 μg biomass C g−1, of which 87 μg C g−1 was fungal and 50 μg C g−1 was bacterial biomass (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Overview of chemical and biological properties of the soil prior to salt exposure

a Standard errors of the means.

b Electrical conductivity in a 1:5 soil-water suspension.

c Measured in a 1:5 soil-water suspension.

d Based on substrate-induced respiration (SIR) measurement.

e Based on ergosterol concentration.

f Mass balance of total microbial biomass and fungal biomass.

Acute toxicity of NaCl to microbial processes.

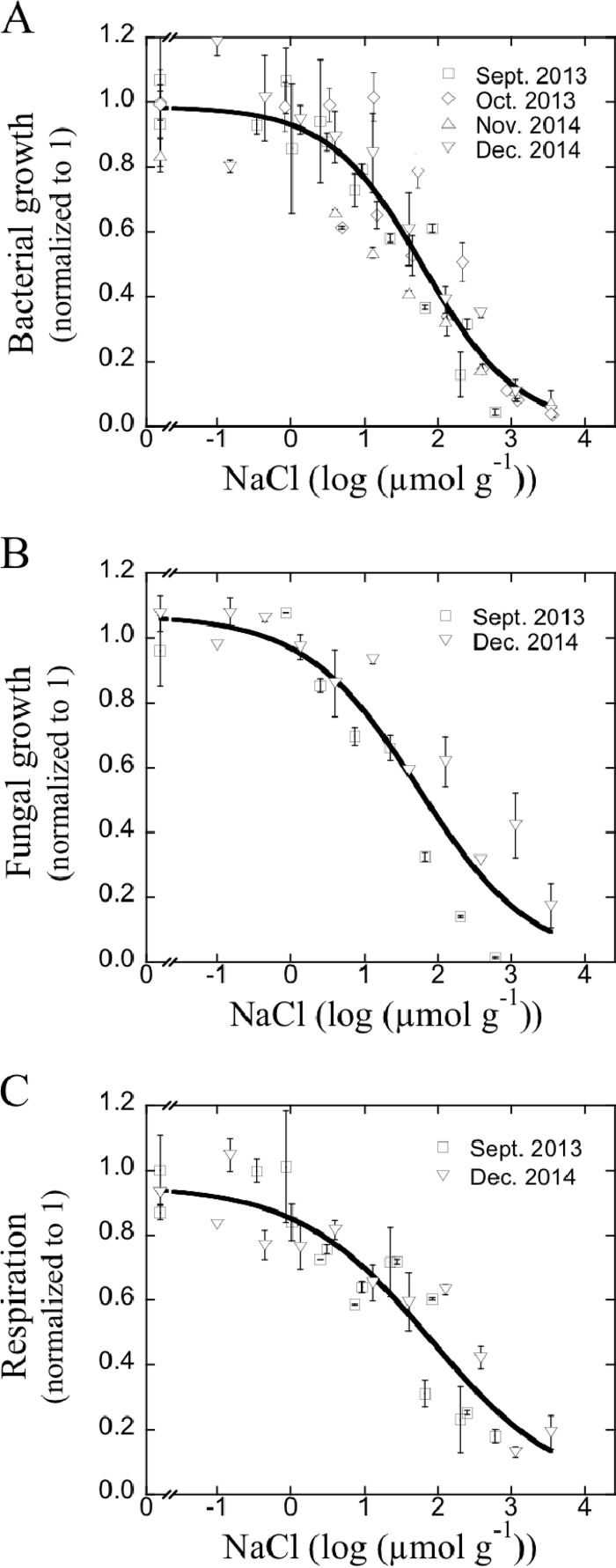

All processes investigated showed clear concentration-response relationships with salinity, with pronounced inhibition at high salt concentrations (Fig. 1 and 2). These concentration-response relationships could be described with a logistic model (R2 values ranging from 0.78 to 0.95 with an average R2 value of 0.88). The acute toxic effects for all of these processes remained unchanged in the interval 1 h to 48 h after salt addition (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). With a longer duration, bacterial growth started to recover between 48 and 96 h, while mineralization and fungal growth remained suppressed for the duration of this comparison. As such, the different standard time frames used for the different endpoints (2 h to 24 h) did not bias the outcome of the comparison. In addition, we also used soil samples sampled at different time points to investigate how robust our assessments were for generalization. A formal comparison of time points showed no differences between soil samples run at different time points. Log(IC50) values estimated using the model ranged from 1.74 for fungal growth, corresponding to 54 μmol NaCl per g soil, to 2.94 for gross N mineralization, corresponding to 870 μmol NaCl per g (Table 2). If microbial responses were compared using the resulting electrical conductivity measured in the salt additions, log(IC50) values ranged from 0.10 for gross nitrification, corresponding to 1.26 dS m−1, to 0.96 for respiration, corresponding to 9.05 dS m−1 (Table 2).

FIG 1.

Concentration-response relationships between salt (NaCl) exposure and bacterial growth measured as leucine incorporation (A), fungal growth measured as acetate incorporation into ergosterol (B), and soil respiration (C). Soil samples were collected from the same site at different time points (represented by different symbols), and data from repeated runs of the experiment were combined into a single inhibition curve. Error bars indicate the standard errors (n = 2).

FIG 2.

Concentration-response relationships between salt (NaCl) exposure and gross N mineralization (A) and gross nitrification (B). Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 2).

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity of microbial processes to exposure to NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4

| Microbial process | Sensitivity toa: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl |

KCl |

Na2SO4 |

K2SO4 |

|||||

| Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | |

| Growthb | ||||||||

| Bacterial | 1.80 (0.10) | 1.60–1.99 | 1.43 (0.21) | 1.02–1.84 | 1.19 (0.17) | 0.85–1.52 | 1.68 (0.29) | 1.11–2.25 |

| Fungal | 1.74 (0.20) | 1.34–2.13 | 2.53 (0.12) | 2.30–2.77 | 2.56 (0.11) | 2.34–2.77 | 2.62 (0.17) | 2.29–2.96 |

| Respiration | 1.90 (0.18) | 1.55–2.25 | 2.66 (0.16) | 2.34–3.00 | 3.12 (0.19) | 2.75–3.50 | No inhibition | |

| Gross N mineralization | 2.94 (0.36) | 2.16–3.72 | ||||||

| Gross nitrification | 1.96 (0.16) | 1.61–2.31 | ||||||

IC50s (measured as μmol salt g−1) corresponding to the salt concentration leading to a 50% inhibition of process rate. Standard errors are given within parentheses. 95% CI is the 95% confidence interval of the IC50.

Bacterial growth was measured as [3H]leucine incorporation into biomass. Fungal growth was measured as [14C]acetate incorporation into ergosterol.

Bacterial growth, fungal growth, and respiration were inhibited by NaCl exposure to a similar degree, with log(IC50) values of 1.80, 1.74, and 1.90, corresponding to NaCl concentrations of 6.3, 5.5, and 7.9 mol liter−1 bacterial suspension or 63, 55, and 79 μmol NaCl per g soil, respectively. There is some indication that gross N mineralization (Fig. 2A), which had a log(IC50) value of 2.94, was less sensitive to NaCl than nitrification [log(IC50) = 1.96] (Fig. 2C). However, there were no significant differences between these processes in sensitivity to NaCl. Gross N mineralization was significantly less sensitive to NaCl than bacterial growth rates. Increasing salinity had no discernible effect on the ratio of C-to-N mineralization rates, which had an overall mass ratio of 9 ± 1.3 (means ± standard errors).

Comparative toxicities of salts.

In the second part of the experiment, we compared the toxicities of different salts on bacterial and fungal growth as well as soil respiration (Table 2 and Fig. 3; also see Fig. S3 to S5 in the supplemental material). While we could not observe any significant differences between bacterial growth, fungal growth, and respiration in response to NaCl exposure, we found that bacterial growth was more sensitive than fungal growth and respiration to KCl [log(IC50) of 1.43] and Na2SO4 [log(IC50) of 1.19] and K2SO4 [log(IC50) of 1.68] (Table 2). These log(IC50) values correspond to 2.7, 1.5, and 4.8 mol liter−1 bacterial suspension or 27, 15, and 48 mg g−1, respectively. Fungal growth and soil respiration were affected by NaCl, KCl, and Na2SO4 to the same degree, while K2SO4 inhibited fungal growth [log(IC50) of 2.62, corresponding to 420 mg g−1] but not respiration (Table 2).

FIG 3.

Dose-response relationships between bacterial growth (A), fungal growth (B), and soil respiration (C) and short-term exposure to different salts (NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4). Data from repeated runs of the experiment were combined into a single inhibition curve. In the control treatments without added salt, the bacterial growth was 42 pmol Leu g−1 h−1, the fungal growth rate was 15 pmol Ac g−1 h−1, and the respiration rate was 1.8 μg CO2 g−1 h−1. Error bars indicate the standard errors (n = 2).

No significant differences between the susceptibility of bacterial growth to the different salts were found (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Fungal growth was significantly more inhibited by NaCl than any of the other studied salts (Fig. 3B and Table 3). KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4 did not differ in their effect on fungal growth rates. Of the salts included in the study, NaCl was the most inhibitory to respiration [log(IC50) of 1.90] (Fig. 3C and Table 2). There was no observable inhibitory effect of K2SO4 on respiration rates, even at concentrations that must have resulted in a saturation of the soil solution (Fig. 3C).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity of microbial processes to the electrical conductivity in a 1:5 soil-water suspension following addition of NaCl, KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4

| Microbial process | Sensitivity toa: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl |

KCl |

Na2SO4 |

K2SO4 |

|||||

| Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | Log(IC50) | 95% CI | |

| Growthb | ||||||||

| Bacterial | 0.26 (0.10) | 0.06 to 0.45 | −0.09 (0.11) | −0.31 to 0.12 | 0.05 (0.10) | −0.14 to 0.25 | 0.51 (0.16) | 0.20 to 0.83 |

| Fungal | 0.67 (0.15) | 0.37 to 0.96 | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.41 to 1.07 | 0.77 (0.11) | 0.55 to 0.98 | 1.02 (0.24) | 0.55 to 1.49 |

| Respiration | 0.96 (0.18) | 0.60 to 1.31 | 0.68 (0.30) | 0.06 to 1.30 | 1.48 (0.21) | 1.06 to 1.89 | No inhibition | |

| Gross N mineralization | 0.94 (0.35) | 0.18 to 1.70 | ||||||

| Gross nitrification | 0.10 (0.15) | −0.23 to 0.43 | ||||||

IC50s (measured as dS m−1) corresponding to the electrical conductivity leading to a 50% inhibition of process rate. Standard errors are given within parentheses. 95% CI is the 95% confidence interval of the IC50.

Bacterial growth was measured as [3H]leucine incorporation into biomass. Fungal growth was measured as [14C]acetate incorporation into ergosterol.

When salinities were expressed as electrical conductivities measured in 1:5 soil-water suspensions, results were, for the most part, similar to those using molar concentrations of salts (Table 3; also see Fig. S6 to S8 in the supplemental material). Of the few observed differences, we found that respiration was significantly less affected by NaCl exposure [log(IC50) of 0.96] than bacterial growth rates [log(IC50) of 0.26]. Respiration also was less affected by Na2SO4 [log(IC50) of 1.48] than both bacterial [log(IC50) of 0.05] and fungal [log(IC50) of 0.77] growth rates. In contrast to what was found using molar concentrations of salts, fungal growth rates were not more sensitive to NaCl than other salts (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Microbial susceptibility to salts.

Microbial growth responses, as well as respiration and N transformation rates, were clearly inhibited by salinity in our experiment. The toxic effects remained stable in the interval of 2 to 48 h after salt application, showing that the window of opportunity to compare toxic effects was rather wide, and the toxic effects were reproducible for repeated samplings of the same soil, between years and seasons, highlighting the robustness of the assessments. The salinity responses of all microbial processes could be well described with a logistic dose-response relationship (Fig. 1 to 3). Our findings suggest that all of the above-described processes could be used as indicators for acute salinity effects on soil microorganisms and, as such, provide effective measures for comparative toxicity assessments.

In saline soil environments, changes in salinity of course would be more gradual than in our experiment. As a consequence, microbial communities have more time to respond to the changing conditions. Sensitive organisms would be outcompeted while tolerant organisms would thrive, resulting in a community change. These adaptations and community shifts could offset some of the inhibiting effect of salinity on the microbial community we document here. Nevertheless, microbial activity remains reduced in soils that experienced high salt concentrations for longer periods of time (12, 14, 20, 23), but it is often unclear to what degree this observed reduction represents a direct effect of salinity. Therefore, our results represent the potential susceptibility of a process to a direct salt exposure in the studied soil, while the degree to which microbial functions can recover from these perturbations remains to be investigated.

We found indications that fungi are more tolerant to acute salt exposure than bacteria for three out of four salts (Fig. 1 and Table 2), with the exception of NaCl (Table 2). It has been suggested that the chitinous cell walls of fungi offer better protection against water loss, which makes them more resistant to changes in moisture (6, 44). It would be reasonable that this also would offer protection against low water potential brought about by increased osmotic concentration. Consistent with this prediction, it has been shown that fungi are better able to cope with high osmotic pressure caused by high concentrations of organic substrates (8, 9). Moreover, the different localization of the proton gradient used for energy generation in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells could make fungi more resistant to changes in the cation concentration outside the cell. In eukaryotic cells, postglycolytic reactions take place in the mitochondria, and the electrochemical potential used to drive ATP synthesis is established across the mitochondrial membrane, whereas in bacteria, the potential needs to be maintained across the cell membrane and therefore is more susceptible to environmental conditions outside the cell (45, 46).

The observation that fungal growth was less affected by acute salt exposure than bacteria suggests, if the finding can be extrapolated, that soil salinization favors fungi over bacteria, which could result in a shift in community composition toward a more fungus-dominated community. In a recent study, an increase in the abundance of fungal biomarkers was observed in response to both increasing concentrations of salts and drying of the soil (47). However, important caveats for this extrapolation need to be carefully considered. The microcosm systems we used were experimentally dispersal limited, meaning that a number of halotolerant or halophilic microorganisms that would dominate the microbial community in naturally saline soils were not present in the nonsaline soil used in this study. While this would not affect the acute responses to salt, the recovery after salt exposure could have been greatly affected. It is possible that bacteria were particularly affected by this bias.

Previous literature reports on the relative dominance of fungi over bacteria in naturally saline soils could be used to evaluate how the acute toxicity responses of microorganisms can be translated to ecosystem effects. To date, these reports are scarce, however, and the few available studies do not unambiguously support the idea that saline soils become more fungus dominated. Saline soils generally have been found to contain low microbial biomass, often with a decreasing ratio of fungal to bacterial biomass (14–17). However, high salinity often coincides with high alkalinity, and it is possible that part of the observed negative dependence of fungi to increasing salinity is driven by the well-known effect of pH (32). Consistent with this, a recent study using a salinity gradient not confounded by soil pH differences observed higher fungal biomass and growth rates in highly saline soils than in nonsaline soils (13). While our knowledge on the effects of salinity is limited in soils, more systematic work is available for aquatic ecosystems. Although hypersaline aquatic environments are dominated by prokaryotes, halophilic aquatic fungi exist that also can grow under highly saline conditions (48). Additionally, eukaryotic decomposers may be underrepresented in most aquatic systems for reasons other than high salinity, e.g., the low availability of particulate organic substrate, which is more abundant in terrestrial environments.

Comparative toxicities of Cl− and SO42− salts.

The inhibitory effect of high concentrations of salts on microbial processes is a combination of both the effects of highly negative osmotic potential and of specific ion toxicity. In the comparison of the toxicities of different salts, we have the opportunity to compare toxicity in terms of both total ionic strength (electric conductivity) and molar concentrations of added salts, thereby disentangling osmotic potential and specific ion toxicity. Our comparison suggests a lower toxicity of SO42− salts than of Cl− salts at a comparable ionic strength for respiration rates but not for microbial growth rates (Table 3).

High concentrations of salts in the cytoplasm of microbial cells can lead to enzyme inhibition due to salting out caused by high ionic strength. In addition, specific ion toxicities have been identified, e.g., some enzymes are particularly sensitive to Na+ and Cl− due to interactions of the ions with inhibitory binding sites (49). A lower toxicity of SO42− ions than Cl− ions to soil microorganisms has been suggested previously (28), e.g., cultured rhizobial strains were found to be less affected by SO42− salts than the corresponding Cl− salts (50). Chloride ions inside cells have been shown to inhibit protein synthesis by preventing the binding of ribosomes to mRNA (51, 52). SO42− ions, on the other hand, can be metabolized by many bacteria and fungi and have no ion-specific toxicity to cellular processes. We could not find clear differences between salts containing Na+ and K+ ions with regard to their toxicity to microbial processes, even though K+ salts previously have been found to be less toxic than Na+ salts (28).

Responses of the microbial growth efficiency to exposure to salts.

Respiration was found to be less sensitive to exposure to SO42− salts than bacterial and fungal growth rates and was affected to a degree similar to that of fungal growth rates by Cl− salts. K2SO4 was not inhibitory to respiration rate and exerted only mild inhibitory effects on growth rates (Tables 2 and 3). This suggests that at high concentrations of SO42− salts, microorganisms still are actively respiring but no longer investing resources into biomass production, supporting the hypothesis that microorganisms allocate substrate away from biomass production toward maintenance functions in response to salt exposure, resulting in decreased MGE. At high concentrations of Cl− salts, in contrast, both growth and respiration were inhibited.

The methods we used to estimate microbial growth rates estimate protein production (bacterial growth) or lipid synthesis (fungal growth). As such, resources used for the synthesis of low-molecular-weight compounds for osmoregulation, such as organic solutes including betaine, ectoine, and various sugars and amino acids, would not be a form of growth captured by these methods. However, these physiological adjustments should affect estimates of MGE only to a minor degree (53). Lowered MGE of the microbial community in response to changes in environmental conditions is frequently interpreted as an indication of a stressed community (5, 54, 55). In our case, relating respiration to newly synthesized biomass would lead to the interpretation that exposure to SO42− salts is more stressful to the community than Cl− salt exposure. If these results of acute responses to salinity can be extrapolated to predict longer-term effects of salts in soil, they would suggest that the accumulation of SO42− salts in the soil can lead to a shift in C allocation from microbial anabolism to catabolism. However, this interpretation is problematically ambiguous. It is equally possible that Cl− salts actually exerted a stronger effect on microorganisms, leading to a higher rate of cell death than exposure to SO42− salts. The lower number of surviving cells could have resulted in a stronger inhibition of respiration together with growth, whereas during SO42− exposure more cells were still alive to respire. This would give the misleading impression of a more stressed community suggested by the reduced MGE, emphasizing that caution needs to be exercised in the interpretation and extrapolation of this endpoint.

Sensitivity of nitrification.

Nitrification rates were not found to have a lower log(IC50) value for salt exposure than the other studied microbial processes (Fig. 2C and Table 2). This contrasts with other studies where nitrification has been identified as a process that is especially sensitive to salinity (24, 56). An important difference between our study and many previous studies concerns the length of incubation after the addition of salts. We measured the acute toxicity of salts shortly after salt exposure, whereas other studies usually measure the response of nitrification and other processes after a longer incubation time. This renders our assessment more directly interpretable than previous assessments. In a longer-term assessment, the measured process is a product of two components: first, the direct suppression or inhibition, and second, the recovery of the process due to sufficient time for a community shift with higher tolerance to salt to occur. Thus, the previous reports of higher sensitivity of nitrification than other processes could be a bias in the recovery of different processes rather than differences in initial tolerance. The steps involved in nitrification are carried out by only a small number of bacteria and archaea. After the addition of salts, microbes carrying out nitrification probably are affected to a degree similar to that of microbes carrying out other less specialized processes, reflected in a similar acute inhibition. However, a high functional redundancy allows alternative groups to quickly take over reduced general processes, such as respiration, thereby masking the inhibiting effect of salts. Conversely, nitrification remains impaired due to the small species pool of nitrifying organisms. Therefore, it appears that nitrification is a useful indicator of toxic effects of chemicals in recent history (57, 58), carrying a signal of inhibition for a long duration after exposure.

Conclusions.

Our results show that salinity exerts a strong inhibitory effect on a range of microbial processes in soil, offering effective measures to assess comparative toxicity. Acute toxic effects of added salts occurred immediately (within 2 h) and lasted for at least 48 h before tolerance induced via community changes led to a recovery of process rates. Fungal growth was found to be less affected by salts than bacterial growth by three of the salts included in the study (KCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4). This difference in tolerance could translate into ecological relevance by favoring fungi over bacteria at high salinities. Nitrification was not found to be more sensitive to exposure to salts than other processes, in contrast to previous findings, probably due to the longer experimental time frame in earlier assessments. Although salinity initially inhibits all microbial processes, the recovery of microbial processes with high functional redundancy, such as respiration, should be significantly faster than that of more specialized processes, such as nitrification, an imbalance that quickly would manifest as an apparent higher sensitivity of nitrification. All studied salts inhibited microbial growth rates to a similar degree, suggesting that the main factor affecting microbial growth rates is the total ionic strength of the soil solution. In contrast, respiration rates were affected less by salts containing SO42− ions than Cl− salts, indicating specific respiration inhibition by Cl− ions. Respiration rates were inhibited less than microbial growth rates at the same concentrations of SO42− salts, which could lead to changes in MGE; however, alternative physiological interpretations stress that this index must be interpreted with caution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet grant 2015-04942), the Royal Physiographical Society of Lund (Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet), and by a Ph.D. studentship awarded by the Centre for Environmental and Climate Research (CEC), Lund University.

Footnotes

This work was part of the Lund University Centre for Studies of Carbon Cycle and Climate Interactions (LUCCI).

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.04052-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rengasamy P. 2006. World salinization with emphasis on Australia. J Exp Bot 57:1017–1023. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Beltran J, Manzur CL. 2005. Overview of salinity problems in the world and FAO strategies to address the problem, p 311–314. In Proceedings of the International Salinity Forum, Riverside, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabolcs I. 1989. Salt-affected soils. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Six J, Frey SD, Thiet RK, Batten KM. 2006. Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Soil Sci Soc Am J 70:555–569. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2004.0347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manzoni S, Taylor P, Richter A, Porporato A, Ågren GI. 2012. Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils. New Phytol 196:79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickland MS, Rousk J. 2010. Considering fungal:bacterial dominance in soils–methods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biol Biochem 42:1385–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waring BG, Averill C, Hawkes CV. 2013. Differences in fungal and bacterial physiology alter soil carbon and nitrogen cycling: insights from meta-analysis and theoretical models. Ecol Lett 16:887–894. doi: 10.1111/ele.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths BS, Ritz K, Ebblewhite N, Dobson G. 1999. Soil microbial community structure: effects of substrate loading rates. Soil Biol Biochem 31:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reischke S, Rousk J, Bååth E. 2014. The effects of glucose loading rates on bacterial and fungal growth in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 70:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzoni S, Schimel JP, Porporato A. 2012. Responses of soil microbial communities to water stress: results from a meta-analysis. Ecology 93:930–938. doi: 10.1890/11-0026.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennon JT, Aanderud ZT, Lehmkuhl BK, Schoolmaster DR. 2012. Mapping the niche space of soil microorganisms using taxonomy and traits. Ecology 93:1867–1879. doi: 10.1890/11-1745.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wichern J, Wichern F, Joergensen RG. 2006. Impact of salinity on soil microbial communities and the decomposition of maize in acidic soils. Geoderma 137:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamble PN, Gaikwad VB, Kuchekar SR, Bååth E. 2014. Microbial growth, biomass, community structure and nutrient limitation in high pH and salinity soils from Pravaranagar (India). Eur J Soil Biol 65:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sardinha M, Müller T, Schmeisky H, Joergensen RG. 2003. Microbial performance in soils along a salinity gradient under acidic conditions. Appl Soil Ecol 23:237–244. doi: 10.1016/S0929-1393(03)00027-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pankhurst CE, Yu S, Hawke BG, Harch BD. 2001. Capacity of fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns to describe differences in soil microbial communities associated with increased salinity or alkalinity at three locations in South Australia. Biol Fertil Soils 33:204–217. doi: 10.1007/s003740000309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Busaidi KTS, Buerkert A, Joergensen RG. 2014. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization at different salinity levels in Omani low organic matter soils. J Arid Environ 100:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasul G, Appuhn A, Müller T, Joergensen RG. 2006. Salinity-induced changes in the microbial use of sugarcane filter cake added to soil. Appl Soil Ecol 31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2005.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blagodatskaya E, Kuzyakov Y. 2013. Active microorganisms in soil: critical review of estimation criteria and approaches. Soil Biol Biochem 67:192–211. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rousk J, Bååth E. 2011. Growth of saprotrophic fungi and bacteria in soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 78:17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Setia R, Marschner P. 2013. Impact of total water potential and varying contribution of matric and osmotic potential on carbon mineralization in saline soils. Eur J Soil Biol 56:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2013.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury N, Nakatani AS, Setia R, Marschner P. 2011. Microbial activity and community composition in saline and non-saline soils exposed to multiple drying and rewetting events. Plant Soil 348:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-0918-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laura RD. 1974. Effects of neutral salts on carbon and nitrogen mineralization of organic matter in soil. Plant Soil 41:113–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00017949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rath KM, Rousk J. 2015. Salt effects on the soil microbial decomposer community and their role in organic carbon cycling: a review. Soil Biol Biochem 81:108–123. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson D, Guenzi W. 1963. Influence of salts on ammonium oxidation and carbon dioxide evolution from soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 27:663–666. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1963.03615995002700060028x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darrah PR, Nye PH, White RE. 1987. The effect of high solute concentrations on nitrification rates in soil. Plant Soil 97:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02149821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClung G, Frankenberger WT. 1987. Nitrogen mineralization rates in saline vs salt-amended soils. Plant Soil 104:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02370619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClung G, Frankenberger WT. 1985. Soil-nitrogen transformations as affected by salinity. Soil Sci 139:405–411. doi: 10.1097/00010694-198505000-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sindhu MA, Cornfield AH. 1967. Comparative effects of varying levels of chlorides and sulphates of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium on ammonification and nitrification during incubation of soil. Plant Soil 27:468–472. doi: 10.1007/BF01376343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasul G, Khan KS, Joergensen RG. 2014. Microbial use of sugarcane filter cake in an artificial saline substrate varying in anion composition and inoculant at different temperatures. Arch Agron Soil Sci 60:327–335. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2013.797571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Li F, Ma Q, Cui Z. 2006. Interactions of NaCl and Na2SO4 on soil organic C mineralization after addition of maize straws. Soil Biol Biochem 38:2328–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson JPE, Domsch KH. 1978. Physiological method for quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 10:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(78)90099-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rousk J, Brookes PC, Bååth E. 2009. Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1589–1596. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02775-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joergensen RG. 2000. Ergosterol and microbial biomass in the rhizosphere of grassland soils. Soil Biol Biochem 32:647–652. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(99)00191-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bååth E. 1994. Thymidine and leucine incorporation in soil bacteria with different cell-size. Microb Ecol 27:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bååth E, Pettersson M, Söderberg KH. 2001. Adaptation of a rapid and economical microcentrifugation method to measure thymidine and leucine incorporation by soil bacteria. Soil Biol Biochem 33:1571–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00073-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rousk J, Bååth E. 2007. Fungal biomass production and turnover in soil estimated using the acetate-in-ergosterol technique. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2173–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IAEA. 2001. Use of isotope and radiation methods in soil and water management and crop nutrition. IAEA, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousk J, Elyaagubi FK, Jones DL, Godbold DL. 2011. Bacterial salt tolerance is unrelated to soil salinity across an arid agroecosystem salinity gradient. Soil Biol Biochem 43:1881–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payton ME, Miller AE, Raun WR. 2000. Testing statistical hypotheses using standard error bars and confidence intervals. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 31:547–551. doi: 10.1080/00103620009370458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blackburn TH. 1979. Method for measuring rates of NH4+ turnover in anoxic marine-sediments, using a 15N-NH4+ dilution technique. Appl Environ Microbiol 37:760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bengtson P, Falkengren-Grerup U, Bengtsson G. 2006. Spatial distributions of plants and gross N transformation rates in a forest soil. J Ecol 94:754–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01143.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishio T, Kanamori T, Fujimoto T. 1985. Nitrogen transformations in an aerobic soil as determined by a 15NH4+ dilution technique. Soil Biol Biochem 17:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(85)90106-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wessel WW, Tietema A. 1992. Calculating gross N transformation rates of 15N pool dilution experiments with acid forest litter–analytical and numerical approaches. Soil Biol Biochem 24:931–942. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(92)90020-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holland EA, Coleman DC. 1987. Litter placement effects on microbial and organic matter dynamics in an agroecosystem. Ecology 68:425–433. doi: 10.2307/1939274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell JB, Sharp WM, Baldwin RL. 1979. Effect of pH on maximum bacterial growth rate and its possible role as a determinant of bacterial competition in the rumen. J Anim Sci 48:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garland PB. 1977. Energy transduction in microbial systems. Symp Soc Gen Microbiol 27:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kakumanu ML, Williams MA. 2014. Osmolyte dynamics and microbial communities vary in response to osmotic more than matric water deficit gradients in two soils. Soil Biol Biochem 79:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gostinčar C, Lenassi M, Gunde-Cimerman N, Plemenitaš A. 2011. Fungal adaptation to extremely high salt concentrations. Adv Appl Microbiol 77:71–96. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387044-5.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serrano R. 1996. Salt tolerance in plants and microorganisms: toxicity targets and defense responses. Int Rev Cytol 165:1–52. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elsheikh EAE, Wood M. 1989. Response of chickpea and soybean rhizobia to salt–osmotic and specific ion effects of salts. Soil Biol Biochem 21:889–895. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(89)90077-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choquet CG, Kamekura M, Kushner DJ. 1989. In vitro protein-synthesis by the moderate halophile Vibrio costicola–site of action of Cl− ions. J Bacteriol 171:880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber LA, Hickey ED, Maroney PA, Baglioni C. 1977. Inhibition of protein-synthesis by Cl−. J Biol Chem 252:4007–4010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neidhardt FC. 1999. Bacterial growth: constant obsession with dN/dt. J Bacteriol 181:7405–7408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson TH, Domsch KH. 1993. The metabolic quotient for CO2 (qCO2) as a specific activity parameter to assess the effects of environmental conditions, such as pH, on the microbial biomass of forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem 25:393–395. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(93)90140-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wardle DA, Ghani A. 1995. A critique of the microbial metabolic quotient (qCO2) as a bioindicator of disturbance and ecosystem development. Soil Biol Biochem 27:1601–1610. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(95)00093-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greaves JE. 1922. Influence of salts on bacterial activities of soil. Bot Gaz 73:161–180. doi: 10.1086/332973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pell M, Stenberg B, Torstensson L. 1998. Potential denitrification and nitrification tests for evaluation of pesticide effects in soil. Ambio 27:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansson GB, Klemedtsson L, Stenstrom J, Torstensson L. 1991. Testing the influence of chemicals on soil autotrophic ammonium oxidation. Environ Toxicol Water Qual 6:351–360. doi: 10.1002/tox.2530060307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.