Abstract

Background

Scabies, or mange as it is called in animals, is an ectoparasitic contagious infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Sarcoptic mange is an important veterinary disease leading to significant morbidity and mortality in wild and domestic animals. A widely accepted hypothesis, though never substantiated by factual data, suggests that humans were the initial source of the animal contamination. In this study we performed phylogenetic analyses of populations of S. scabiei from humans and from canids to validate or not the hypothesis of a human origin of the mites infecting domestic dogs.

Methods

Mites from dogs and foxes were obtained from three French sites and from other countries. A part of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene was amplified and directly sequenced. Other sequences corresponding to mites from humans, raccoon dogs, foxes, jackal and dogs from various geographical areas were retrieved from GenBank. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the Otodectes cynotis cox1 sequence as outgroup. Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analysis approaches were used. To visualize the relationship between the haplotypes, a median joining haplotype network was constructed using Network v4.6 according to host.

Results

Twenty-one haplotypes were observed among mites collected from five different host species, including humans and canids from nine geographical areas. The phylogenetic trees based on Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses showed similar topologies with few differences in node support values. The results were not consistent with a human origin of S. scabiei mites in dogs and, on the contrary, did not exclude the opposite hypothesis of a host switch from dogs to humans.

Conclusions

Phylogenetic relatedness may have an impact in terms of epidemiological control strategy. Our results and other recent studies suggest to re-evaluate the level of transmission between domestic dogs and humans.

Keywords: Sarcoptes scabiei, Scabies, Sarcoptic mange, Humans, Dogs, Canids, Host switch, Phylogenetic analysis

Background

Scabies, or mange as it is called in animals, is an ectoparasitic contagious infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei [1–4]. This neglected and emerging/re-emerging disease is a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated number of cases in humans of over 100 million in 2010 [5]. Sarcoptic mange is also an important veterinary disease leading to significant morbidity and mortality in wild and domestic animals. It affects more than 100 species of mammals worldwide including companion, livestock, and wild animals and it is an emerging problem in many countries [3, 6]. For many years, host-associated populations of S. scabiei have been taxonomically divided into morphologically indistinguishable varieties [3, 7, 8]. The host-specificity of these varieties is still controversial, and current studies are investigating whether they belong or not to different species. Cross-infectivity was observed experimentally on some occasions [4, 9, 10]. Natural apparent cross-infectivity has been recently reported in sympatric wild animal host populations [11–14]. Transmission of scabies mites between other species and humans are common, usually leading to clinically moderate and self-limiting forms, though they may persist for several weeks or in rare cases, until treated [7, 15–20]. In particular, the domestic dog is reportedly the most frequent non human reservoir of mites infecting humans, which may have some implications in term of transmission and control of scabies [21–24].

A widely accepted hypothesis, though never substantiated by factual data, suggests that humans and protohumans were the initial source of animal contamination, dogs and other domestic animals being infested by human contacts and themselves a source for other species of wildlife [3, 4, 7, 25]. In this study we performed phylogenetic analyses of populations of S. scabiei in humans and in canids to validate or not the hypothesis of a human origin of the mites infecting domestic dogs.

Methods

Ethical approval

Mites from humans included in this work were obtained in a study reviewed and approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes (institutional review board) of the ethic committee CPP-Ile-de-France X (approval# 2012/10/23); informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Collection of S. scabiei mites

Mites from dogs and foxes (Vulpes vulpes) were obtained from the collection of the Parasitology Department of the Veterinary College of Alfort, Maisons-Alfort, France and two other French sites, and from other countries (Table 1). All cases were independent; only one mite per different dog was included in the study.

Table 1.

List of Sarcoptes scabiei sequences used in this study

| Haplotype | Sample name | Host | Scientific name | Location | GenBank reference | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | canis10 | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | Australia | AY493391 | [35] |

| 2 | canis202 | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | Australia | AY493392 | [35] |

| 3 | canis22 | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | USA | AY493393 | [35] |

| 3 | Sc38 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821008 | [12] |

| 3 | Sc24 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821006 | [12] |

| 3 | Sc20 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821005 | [12] |

| 3 | S16 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -a | [32] |

| 3 | dog3_china | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KT961022 | This study |

| 3 | dog_italy | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | Italy | KT961025 | This study |

| 3 | dog1_france | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | France | KT961029 | This study |

| 3 | fox1_france | Fox | Vulpes vulpes | France | KT961030 | This study |

| 3 | fox2_france | Fox | Vulpes vulpes | France | KT961031 | This study |

| 3 | fox3_france | Fox | Vulpes vulpes | France | KT961032 | This study |

| 4 | canis19 | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | Australia | AY493394 | [35] |

| 5 | canis9 | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | USA | AY493395 | [35] |

| 6 | Sc135 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821012 | [12] |

| 6 | Sc108 | Dog | Canislupus familiaris | Japan | AB821011 | [12] |

| 6 | Sc34 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821007 | [12] |

| 6 | Sc18 | Raccoon dog | Nyctereutes procyonoides | Japan | AB821004 | [12] |

| 6 | dog2ch | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KJ499544 | [33] |

| 7 | dog1ch | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KJ748527 | [33] |

| 8 | dog3ch | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KJ499545 | [33] |

| 9 | dog4ch | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KJ748529 | [33] |

| 10 | dog5ch | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KJ748528 | [33] |

| 11 | Canis aureus | Jackal | Canis aureus | Israel | KP987792 | [36] |

| 11 | Vulpes | Fox | Vulpes vulpes | Israel | KP987794 | [36] |

| 11 | S42 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -b | [32] |

| 12 | hominis208 | Human | Homo sapiens | Australia | AY493382 | [35] |

| 12 | S60 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 1 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 2 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 9 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 4 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 5 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | 7 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S14 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S45 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S46 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S47 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S48 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S59 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 12 | S74 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -c | [32] |

| 13 | hominis13 | Human | Homo sapiens | Australia | AY493383 | [35] |

| 14 | hominis14 | Human | Homo sapiens | Australia | AY493384 | [35] |

| 15 | S32 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | KR058184 | [32] |

| 15 | S7 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S9 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | 10 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S12 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S15 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S20 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S21 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S27 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S11 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S25 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S29 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S38 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S40 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S44 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S50 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S51 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S56 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S30 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S34 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S39 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S57 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S8 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | 13 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | 15 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | 20 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S69 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 15 | S71 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -d | [32] |

| 16 | S58 | Human | Homo sapiens | France | KR058186 | [32] |

| 17 | 8 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | -e | [32] |

| 18 | 18 M | Human | Homo sapiens | France | KR058187 | [32] |

| 19 | dog1_china | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KT961021 | This study |

| 19 | dog5_china | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KT961023 | This study |

| 20 | dog4_china | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | China | KT961028 | This study |

| 20 | dog2_france | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | IDF/France | KT961024 | This study |

| 20 | dog_SthAfr | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | South Africa | KT961026 | This study |

| 21 | dog_thd | Dog | Canis lupus familiaris | Thailand | KT961027 | This study |

aThis sequence is identical to that of canis22 (AY493393)

bThis sequence is identical to that of waterbuffalo 37025 (AB779588)

cThis sequence is identical to that of hominis205 (AY493382)

dThis sequence is identical to that of S32 (KR058184)

eThis sequence is identical to that of PIG1 (KR058185)

DNA extraction and gene amplification

Mite genomic DNA was individually extracted with NucleoSpin Tissue kit, Macherey-Nagel, Germany [26, 27]. A part of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene was amplified. PCR was carried out in 50 μl and reaction mixture contained 1X PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM of dNTPs, 1.25U DNA polymerase AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) and 0.25 μM of primer (NavF : 5’-TGATTTTTTGGTCACCCAGAAG-3’; NavR : 5’-TACAGCTCCTATAGATAAAAC-3’) [28]. Amplification conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturing at 94 °C for 30s, annealing at 51 °C for 30s, and extending at 72 °C for 40s and a 5 min of final extension at 72 °C.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

The PCR-amplified products of 400 bp were purified and directly sequenced. The Otodectes cynotis cox1 sequence (KF891933) was retrieved from GenBank. Multiple sequence alignments of nucleotide sequences in this study and sequences available from GenBank (n = 81) were generated using MAFFT v.6.951. The dataset was analyzed with Maximum Likelihood using MEGA5 and RAxML-HPC v7.0.4 under General Time-Reversible (GTR + G) model and Bayesian Inference analysis. Support of internal branches was evaluated by non-parametric bootstrapping with 500 replicates. Bayesian Inference analysis was performed with MrBayes v.3.2.1 conducting in two simultaneous runs with four parallel Markov chains (one cold and three heated) for 1 million generations, sampling every 1000 generations and discarding the first 25 % of samples as burn-in. Potential Scale Reduction Factor approached 1.0 and average of split frequencies under 0.01 were used for examining convergence. All trees were visualized using FigTree with Otodectes cynotis as outgroup (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree). To visualize the relationships between haplotypes, a median joining haplotype network of cox1 sequence was constructed using Network v4.6 according to host.

Results

The sequences of cox1 fragment were obtained in mites from nine dogs and three foxes (Table 1). All sequences were deposited [GenBank: KT961021-KT961032]. Other sequences corresponding to 50 mites from humans, raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) (n = 6), fox (n = 1), jackal (Canis aureus) (n = 1) and domestic dogs (n = 11) and from various geographical areas were retrieved from GenBank and from a previous study (Table 1).

All of the successfully sequenced samples were assigned to only one haplotype. In all, 21 haplotypes were observed among mites collected from five different host species, including humans and canids, and nine geographical areas (Table 1). Seven haplotypes were observed among mites collected in humans (H12-H18); two haplotypes were shared with mites collected from canids and human (H3 and H11) and 12 haplotypes (H1-H2, H4-H10, H20-H21) were observed among mites collected from canids.

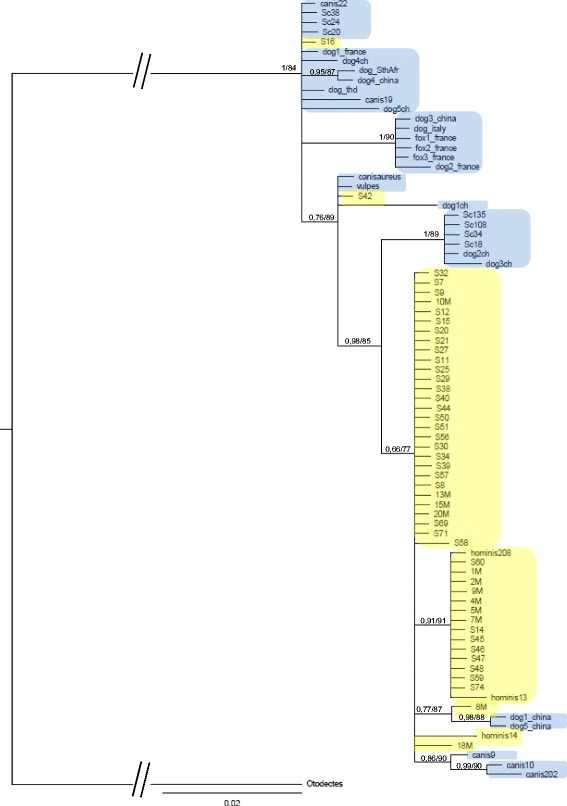

Sequences from dogs (n = 20), raccoon dogs (n = 6), foxes (n = 4), Jackal (n = 1) and humans (n = 50) were used to construct the phylogenetic trees based on Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses. They showed similar topologies with few differences in node support values (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree among Sarcoptes scabiei from canids and humans. Bootstrap values are indicated above branches, left of the slash for Maximum Likelihood and right of the slash for Bayesian Inference. Tree was rooted with Otodectes cynotis (KF891933). Blue shading: mites collected from canids. Yellow shading: mites collected from humans

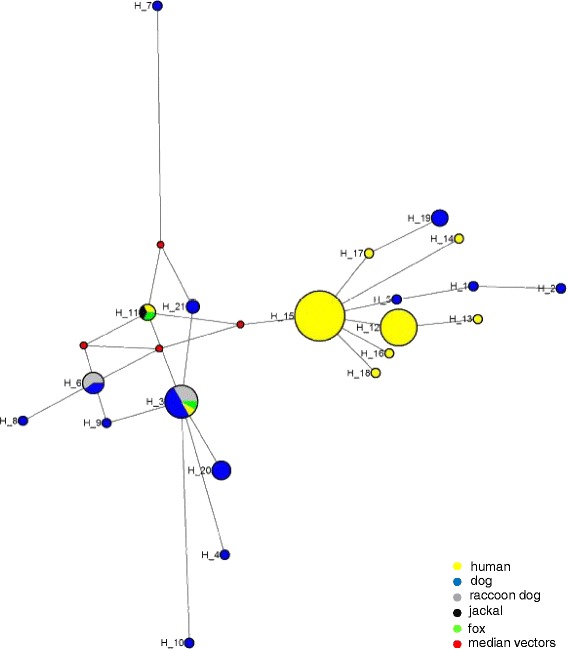

The haplotype network showed two distinct populations of mites, a relatively diverse population from dogs and other canids, and a more homogeneous population from humans (Fig. 2). In addition, values of haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π) indicated a larger genetic diversity for S. scabiei mites collected in dogs than for those collected in humans (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Haplotype map of Sarcoptes scabiei from canids and humans inferred under median joining. Size of circles is proportional to haplotype frequency. Median vectors correspond to possibly extant un-sampled sequences or extinct ancestral sequences

Table 2.

Estimates of genetic diversity of Sarcoptes scabiei mites from humans and canids

| No. of sequences | No. of haplotypes | Haplotype diversity (Hd) (± sd) | Nucleotide diversity (π) ± (sd) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | 50 | 9 | 0.606 (0.056) | 0.0022 (0.00041) |

| Dogs | 20 | 13 | 0.942 (0.034) | 0.011 (0.0012) |

| Canids (including dogs) | 31 | 14 | 0.871 (0.046) | 0.0087 (0.0011) |

Discussion

The historical hypothesis about the origin of S. scabiei in dogs is a transfer of parasites from humans to their domestic dogs. Under this scenario, the population of mites from humans should be basal in the phylogenetic tree. This is not what was observed in the present phylogenetic analyses. Our data were not consistent with a human origin of S. scabiei in dogs. On the contrary, our results did not exclude the opposite hypothesis of a host switch from dogs to humans. The haplotype network showed also that, on two occasions, haplotypes from dogs, H19 and H5, H1, H2, seemed to derive from S. scabiei mites in humans. Being possibly of canine origin, mites infecting humans may in some occasions return to canine hosts.

The fact that non-human primates are not affected by scabies (or the few times it was described it was considered that this was via a human contamination [29]) while the brother genera of Sarcoptes (Otodectes and Psoroptes) infect carnivores or sheep (phylogenetically closer to dogs than human) reinforces the hypothesis of a canine origin of scabies and a host transfer to humans [30].

According to the historical hypothesis, behavioral transmission between humans and dogs occurred when humans domesticated various species of animals at the beginning of agriculture and sedentarization [3]. The origin of the domestic dog is still debated. Recent data indicate that domestic dogs evolved from a group of wolves that came into contact with hunter-gatherers between 18,800 and 32,100 years ago [31]. Those data contradict the historical hypothesis as agriculture was developed later, around 11,500 years ago.

We included all the cox1 nucleotide sequences of S. scabiei available in GenBank that were from canids and from all human mites sharing the same clade as canid mites in published phylogenetic studies (Table 1). Cox1 gene, including a very high number of polymorphisms, was found to be valid and best suited for this type of phylogenetic analysis according to previous studies on the same topic [32, 33].

Mites of human origin were collected in only two countries, mostly in France. It does not necessarily mean that patients acquired their mites in France. Indeed, various ethnic communities are represented among the outpatients that visit our departments (about one third are immigrants) and it is likely that a not-insignificant number of cases of scabies were acquired abroad. However, we cannot formally exclude that a sampling bias could have led us to underestimate the diversity of cox1 in human mites.

Host switching promotes S. scabiei diversification and reflects the exceptional dissemination potential of these mites among various species of mammals. Scabies spreading in wild populations may occur on an epidemic mode and may be devastating for naive populations because of the lack of immunity [34]. It may be underlined that transmission between dogs and humans still occurs. In a recent study, Zhao et al., using cox1 for phylogenetic analysis, reported that mites from dogs in China, Australia and USA clustered with mites collected from Australian people [33]. Those authors concluded that humans could be infected with mites from dogs. The present data and our previous results on this point are in agreement with those authors [32]. Those authors also conclude that geographical isolation was observed between human mites. The aim of our study was not to explore a possible geographic effect on Sarcoptes evolution but to present documented data on the possibility that humans are the initial source of canine mange. We agree that geographic clustering occurs in human Sarcoptes evolution [32] but this seems not to be the case for canid Sarcoptes. Indeed, our phylogenetic tree argues against any geographical effect on canid Sarcoptes evolution because most of the clades are made of taxa from different locations (for example a clade shows that foxes and dogs from France clustered with dogs from China in Fig. 1). Nevertheless, other studies including more S. scabiei mites from canids originating from different locations are needed to answer this question.

Two mites collected in humans, S16 and S42, belonging to haplotypes shared by mites from humans and canids, clustered with mites collected in canids in the present study (Fig. 1 and Table 1). In addition, some other haplotypes may be shared by different hosts, as shown in this study and in other works [20, 32]. Thus, the historical hypothesis of the “high degree of host- specificity and low degree of cross-infectivity of S. scabiei” [10] is challenged.

Conclusions

Phylogenetic relatedness may have an impact in terms of epidemiological control strategy. Our results and other recent studies suggest to re-evaluate the level of transmission between humans and animals and between domestic and wild animals [16, 30]. In particular, it may be useful to know the proportion of human scabies contracted from infected dogs and also whether cases of sarcoptic mange in dogs may be due to mites from humans.

Control programs for human scabies should consider concomitant programs for mange in dogs to optimize efficacy. In addition, the existence of some degree of gene exchange between host-associated populations should be considered for the surveillance of the emergence and diffusion of insecticide resistance.

Acknowledgements

Fang Fang was supported by the Fund of the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VA, FA, and RD conceived the study. AI, FF, FB, CB, OC, JG and WH collected the samples and revised the manuscript. VA, FA, and FF carried out the molecular genetic studies. AI, FB, CB, OC, JG participated in data acquisition. VA and FA were responsible for the phylogenetical analyses. VA and RD drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Valérie Andriantsoanirina, Email: landyvalerie@gmail.com.

Fang Fang, Email: fang8730@163.com.

Frédéric Ariey, Email: frederic.ariey@yahoo.fr.

Arezki Izri, Email: arezki.izri@aphp.fr.

Françoise Foulet, Email: francoise.foulet@aphp.fr.

Françoise Botterel, Email: francoise.botterel@aphp.fr.

Charlotte Bernigaud, Email: cberni@hotmail.fr.

Olivier Chosidow, Email: olivier.chosidow@aphp.fr.

Weiyi Huang, Email: wyhuang@gxu.edu.cn.

Jacques Guillot, Email: jguillot@vet-alfort.fr.

Rémy Durand, Email: remy.durand@aphp.fr.

References

- 1.Chosidow O. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hengge U, Currie BJ, Lupi O, Schwartz RA. Scabies: an ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769–79. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currier RW, Walton SF, Currie BJ. Scabies in animals and humans: history, evolutionary perspectives, and modern clinical management. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1230:E50–E60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alasaad S, Rossi L, Heukelbach J, Pérez JM, Hamarsheh O, Otiende M, et al. The neglected navigating web of the incomprehensibly emerging and re-emerging Sarcoptes mite. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;17:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–34. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world: its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microb Infect. 2012;18:313–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fain A. Epidemiological problem of Scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1978.tb06040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mounsey KE, McCarthy JS, Walton SF. Scratching the itch: new tools to advance understanding of scabies. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arlian LG, Runyan RA, Estes SA. Cross infestivity of Sarcoptes scabiei. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:979–86. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(84)80318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornstein S. Experimental infection of dogs with Sarcoptes scabiei derived from naturally infected wild red foxes (Vulpes vulpes): clinical observations. Vet Dermatol. 1991;2:151–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.1991.tb00126.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renteria-Solis Z, Min AM, Alasaad S, Müller K, Michler FU, Schmäschke R, et al. Genetic epidemiology and pathology of raccoon-derived Sarcoptes mites from urban areas of Germany. Med Vet Entomol. 2014;28(Suppl.1):98–103. doi: 10.1111/mve.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makouloutou P, Suzuki K, Yokoyama M, Takeuchi M, Yanagida T, Sato H. Involvement of two genetic lineages of Sarcoptes scabiei mites in a local mange epizootic of wild mammals in Japan. J Wildlife Dis. 2015;51:69–78. doi: 10.7589/2014-04-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuyama R, Yabusaki T, Kuninaga N, Morimoto T, Okano T, Suzuki M, et al. Coexistence of two different genotypes of Sarcoptes scabiei derived from companion dogs and wild raccoon dogs in Gifu, Japan: The genetic evidence for transmission between domestic and wild canids. Vet Parasitol. 2015;212:356–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holz PH, Orbell GMB, Beveridge I. Sarcoptic mange in a wild swamp wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) Aust Vet J. 2011;89:458–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker IK. Sarcoptes scabiei infestation of a koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), with probable human involvement. Aust Vet J. 1974;50:528. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1974.tb14068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skerratt LF, Beveridge I. Human scabies of wombat origin. Aust Vet J. 1999;77:607. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1999.tb13202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menzano A, Rambozzi L, Rossi L. Outbreak of scabies in human beings, acquired from chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) Vet Rec. 2004;155:568. doi: 10.1136/vr.155.18.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazargani TT, Hallan JA, Nabian S, Rahbari S. Sarcoptic mange of gazelle (Gazella subguttarosa) and its medical importance in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1517–20. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skerratt LF, Campbell NJ, Murrell A, Walton S, Kemp D, Barker SC. The mitochondrial 12S gene is a suitable marker of populations of Sarcoptes scabiei from wombats, dogs and humans in Australia. Parasitol Res. 2002;88:376–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-001-0556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andriantsoanirina V, Ariey F, Izri A, Bernigaud C, Fang F, Guillot J, et al. Wombats acquired scabies from humans and/or dogs from outside Australia. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:2079–83. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emde R. Sarcoptic mange in humans. A report of an epidemic of 10 cases of infections by Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:633–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1961.01580160097017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EB, Claypoole TF. Canine scabies in dogs and in humans. JAMA. 1967;199:59–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03120020053008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomsett LR. Mite infestations of man contracted from dog and cats. BMJ. 1968;3:93–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5610.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aydingöz IE, Mansur AT. Canine scabies in Humans: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:104–6. doi: 10.1159/000327378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amer S, El Wahab TA, Metwaly Ael N, Ye J, Roellig D, Feng Y, et al. Preliminary molecular characterizations of Sarcoptes scabiei (Acari: Sarcoptidae) from farm animals in Egypt. Plos One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soglia D, Rambozzi L, Maione S, Spalenza V, Sartore S, Alasaad S, et al. Two simple techniques for the safe Sarcoptes collection and individual mite DNA extraction. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1465–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andriantsoanirina V, Izri A, Botterel F, Foulet F, Chosidow O, Durand R. Molecular survey of knockdown resistance to pyrethroids in human scabies mites. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O139–41. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fournier D, Bride JM, Navajas M. Mitochondrial DNA from a spider mite: isolation, restriction map and partial sequence of the cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene. Genetica. 1994;94:73–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01429222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein JA, Didier PJ. Nonhuman primate dermatology: a literature review. Vet Dermatol. 2009;20:145–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2009.00742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amer S, Abd El Wahab T, El Naby Metwaly A, Feng Y, Xiao L. Morphologic and genotypic characterization of Psoroptes mites from water buffaloes in Egypt. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thalmann O, Shapiro B, Cui P, Schuenemann VJ, Sawyer SK, Greenfield DL, et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science. 2013;342:871–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1243650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andriantsoanirina V, Ariey F, Izri A, Bernigaud C, Fang F, Charrel R, et al. Sarcoptes scabiei mites in humans are distributed into three genetically distinct clades. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Y, Cao ZG, Cheng J, Hu L, Ma JX, Yang YJ, et al. Population identification of Sarcoptes hominis and Sarcoptes canis in China using DNA sequences. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1001–10. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skerratt LF, Martin RW, Handasyde KA. Sarcoptic mange in wombats. Aust Vet J. 1998;76:408–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1998.tb12389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walton SF, Dougall A, Pizzutto S, Holt D, Taplin D, Arlian LG, et al. Genetic epidemiology of Sarcoptes scabiei (Acari: Sarcoptidae) in northern Australia. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:839–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erster O, Roth A, Pozzi PS, Bouznach A, Shkap V. First detection of Sarcoptes scabiei from domesticated pig (Sus scrofa) and genetic characterization of S. scabiei from pet, farm and wild hosts in Israel. Exp Appl Acarol. 2015;66:605–12. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9926-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]