Abstract

This paper presents the rationale for a 24-week, randomized trial designed to test whether risperidone plus structured parent training would be superior to risperidone only on measures of noncompliance, irritability and adaptive functioning. In this model, medication reduces tantrums, aggression and self-injury; parent training promotes improvement in noncompliance and adaptive functioning. Thus, medication and parent training target related, but separate, outcomes. At week 24, the medication was gradually withdrawn to determine whether subjects in the combined treatment group could be managed on a lower dose or off medication without relapse. Both symptom reduction and functional improvement are important clinical treatment targets. Thus, experimental evidence on the beneficial effects of combining pharmacotherapy and exportable behavioral interventions is needed to guide clinical practice.

Keywords: Autism, Clinical trial methodology, Risperidone, Behavior therapy

Introduction

Pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs) including autism, Asperger's disorder and PDD-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) are chronic conditions of early childhood onset affecting as many as 6 children per 1,000 (Fombonne 2003). Autism is defined by impairments in social interaction and communication as well as repetitive behavior and restricted interests. By contrast, children with Asperger's Disorder do not show prominent delays in communication. PDD-NOS is marked by social disability, but the communication delay and repetitive behaviors may not be as severe as in autism. Children with PDDs may also exhibit tantrums, aggression, self-injury, disruptive behavior, hyperactivity and noncompliance (RUPP Autism Network 2002, 2005a). These serious behavioral problems pose considerable challenge for parents, interfere with learning and activities of daily living, and warrant intervention.

Children with PDD often require multimodal treatment including specialized educational interventions (National Research Council 2001), behavior therapy (Schreibman 2000; Smith et al. 2000) and medication (Scahill and Martin 2005). The goals of comprehensive intervention programs are to decrease the core symptoms of PDD, decrease maladaptive behavior and enhance overall development. However, there is incomplete consensus on intensity, duration and essential programmatic components suggesting that more study is needed (National Research Council 2001; Lord et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2007).

Behavioral interventions based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) have been used to reduce behavioral problems or to enhance daily living skills, functional communication or joint attention (Lovaas 1987). Using single-subject designs, several specific behavioral techniques have been shown to be effective when delivered by experts. Despite these advances, dissemination of effective behavioral interventions has been limited and randomized controlled trials are few in number (Smith et al. 2007).

The empirical basis for pharmacotherapy in children with PDD has expanded in recent years (see Scahill and Martin 2005). To date, the use of medication in PDD has mainly focused on target symptoms such as: tantrums, aggression, and self-injury; repetitive behavior; or hyperactivity (Hollander et al. 2005; RUPP Autism Network 2002, 2005a) with varying degrees of success.

In a previous 8-week, randomized trial we showed that risperidone was superior to placebo in reducing serious behavioral problems such as tantrums, aggression, and self injury in children with autism (RUPP Autism Network 2002; McDougle et al. 2005). Using a similar design, Shea et al. (2004) replicated these findings. In our study, children who remained on medication for 6 months showed modest gains in daily living skills, socialization and communication (Williams et al. 2006). To build on these results, we set out to evaluate the combined effects of medication and parent training (PT) in children with PDD and serious behavioral problems. We proposed that the addition of a structured PT program could contribute to a decrease in serious behavioral problems, promote greater compliance in activities of daily living and improve adaptive functioning when compared to medication alone. The primary aim of this paper is to describe the design challenges and decisions made in planning a multisite trial comparing risperidone alone to risperidone plus parent training in children with PDD accompanied by serious behavioral problems. The secondary aim is to propose a model in which two treatments (medication and PT) may be directed at related but separate outcomes.

Methods

Design

Table 1 shows the design decisions and rationale in planning this multisite trial. The study was designed to test several hypotheses. Compared to medication only group: (1) the combined treatment group would show greater improvement on noncompliant and serious behavioral problems; (2) the combined treatment would contribute to greater gains in daily living skills; (3) the combined treatment would result in a lower rate of relapse (i.e., return of tantrums, aggression and/or self-injury) upon medication discontinuation.

Table 1.

Summary of design decisions for risperidone only versus risperidone ± PT

| Design decision | Rationale |

|---|---|

| No placebo group in acute phase | Efficacy of risperidone already demonstrated; equipoise no longer present |

| No PT only group | Focus on additive effects of PT; not drug versus PT |

| Use of 2:1 randomization | Facilitate recruitment |

| Selection of outcome measuresa | Examine ↓ maladaptive behavior via drug; examine ↑ compliance and adaptive behavior via PT |

| Selection of 24-week randomized trial | Ensure sufficient time for positive effects of PT |

| Use of aripiprazole after failure of risperidone in acute phase | Guard against attrition in the 24-week trial |

| Inclusion of 10-week medication discontinuation phase | Evaluate rate of relapse in drug only versus combined treatment |

Home situations questionnaire, Vineland Adaptive Behavior scales, Aberrant Behavior Checklist Irritability subscale, improvement item on the Clinical Global Impressions

The study was divided into two phases. The first phase was a 24-week randomized trial in which 124 subjects were randomly assigned in a planned 2:1 ratio to risperidone plus PT or risperidone alone. The unbalanced randomization was based on an assumption that families would prefer the combined treatment over the drug only treatment. The second phase was a 10-week discontinuation trial that included all subjects showing a positive response to treatment (described below) at week 24. During the Discontinuation phase, the medication was gradually withdrawn to evaluate the rate of relapse in each group over the 10-week period.

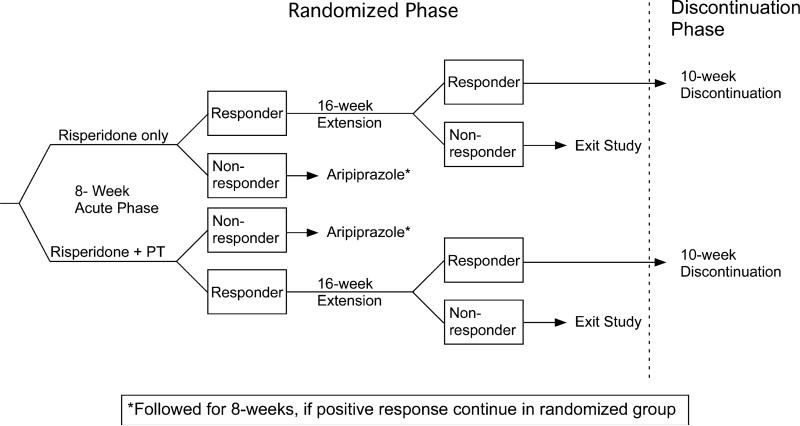

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the study design. From this diagram it is clear that week 8 in the randomized trial was an important nodal point in the study. To continue with risperidone beyond week 8, subjects in both treatment groups had to show at least 25% improvement on the Irritability subscale of the parent-completed Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and a score of Much Improved or Very Much Improved on the Clinical Global Impression for improvement rated by a clinician blinded to treatment assignment. This same definition of positive response was also used in the prior risperidone trial (RUPP Autism Network 2002). Children who did not meet positive response criteria were offered treatment with aripiprazole and continued in their randomly assigned group (medication only or medication plus PT).

Fig. 1.

Design of multiphase trial showing nodal points at weeks 8 and 24. Note: the use of aripiprazole for risperidone non-responders. These subjects continued in their originally randomized group (medication only or medication plus PT)

In the Discontinuation phase, the medication was gradually withdrawn over a 6-week period with regular monitoring for up to four additional weeks. As in our previous trial, subjects who showed a 25% increase in the ABC Irritability subscale and a rating of Much Worse or Very Much Worse on the CGI-I met relapse criteria and the medication was rein-stituted (RUPP Autism Network 2005b).

Subjects and Setting

The Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network sites included: Indiana University, Ohio State University and Yale University. After obtaining informed content, all subjects had a comprehensive assessment to establish diagnosis, intellectual capacity, adaptive functioning, severity of behavioral problems and medical fitness for the trial. Study entry required the presence of PDD accompanied by moderate to severe tantrums, aggression and self-injury (see Table 2). To screen for other DSM-IV disorders, parents completed the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory (Gadow et al. 2005). Eligible subjects were randomized within site and balanced on Tanner stage (Tanner 1 or 2 vs. all other), gender, autistic disorder diagnosis. Once randomized, all subjects were assessed weekly for 8 weeks. From week 8 to 24, subjects were seen monthly for assessment. In the Discontinuation phase, subjects resumed weekly visits. Two clinicians followed each subject through all phases of the trial. The treating clinician, who monitored adverse effects and adjusted the dose of the medication, remained blind to treatment assignment unless clinical care required consultation with the behavior therapist. The independent evaluator, who rated therapeutic response, remained blind to treatment assignment throughout the trial. The PT was delivered by a third clinician trained to reliability in the PT manual (Johnson et al. 2007).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for risperidone only versus risperidone + PT

| Inclusion criteria |

| Outpatients, males and females between the ages of 4 and 13 years; body weight ≥15 kg |

| DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder-NOS (established by clinical assessment, corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Interview-revised) |

| ≥18 on parent-rated Irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist |

| ≥Moderate on the Clinical Global Impressions Severity scale (clinical assessment) |

| Medication-free for at least 2 weeks for all psychotropic medications (4 weeks for fluoxetine or depot antipsychotics) |

| Stable seizure disorder as evidenced by stable dosage of anticonvulsant medication for at least 4 weeks and no seizures for at least 6 months |

| IQ of ≥35 as measured by the Stanford-Binet V, Revised Leiter, or Mullen |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Females with a positive Beta HCG pregnancy test |

| Evidence of a prior adequate trial of risperidone (at least 2 weeks of treatment at 1.5 mg/day) |

| Evidence of hypersensitivity to risperidone (defined as allergic response [e.g., skin rash]) |

| History of neuroleptic malignant syndrome |

| DSM-IV diagnosis of Rett's Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (clinical assessment and ADI-R) |

| Lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia, another psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder (clinical assessment aided by Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory) |

| Current psychiatric condition (e.g., depression) requiring an alternative treatment (clinical assessment aided by Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory) |

| A significant medical condition identified by history, physical examination or laboratory tests |

Measures

The study outcomes focused on three domains: serious behavioral problems (e.g., tantrums, aggression and self-injury), noncompliance and adaptive functioning. Serious behavioral problems and noncompliance were assessed by parent-completed ABC Irritability subscale and the Home Situations Questionnaire (HSQ), respectively. Change in overall functioning was assessed by the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement score (CGI-I). Adaptive behavior was assessed on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior scales (Vineland). These essential outcome measures are described below. Table 2 includes the methods and measures used in the trial. PDD diagnostic measures, medical and intellectual assessments were conducted pre-treatment to confirm eligibility and to characterize the sample. Most outcome measures were collected every 2 weeks until week 8 and every 4 weeks until week 24. The full Vineland was collected pre-treatment and week 24. The Daily Living section was also obtained at week 16.

Aberrant Behavior Checklist

This 58-item, informant-based scale includes five subscales: I. Irritability (15 items); II. Social Withdrawal (16 items); III. Stereotypic Behaviors (7 items); IV. Hyperactivity (16 items); and V. Inappropriate Speech (4 items). The ABC is reliable, valid, sensitive to treatment effects and has normative data in developmental disabled children (Aman et al. 1985, 1987; RUPP Autism Network 2002; Brown et al. 2002). The Irritability subscale was used to evaluate treatment effects on tantrums, aggression and self injury, which brought the child into the study.

Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I)

The CGI-I 7-point scale measures overall symptomatic change compared to baseline (Guy 1976). Scores range from one (Very Much Improved) through four (Unchanged) to seven (Very Much Worse). Although the CGI-I focused mainly on serious behavioral problems, the independent evaluators were free to consider other positive or negative effects on the child's behavior when making the rating.

Home Situations Questionnaire

The Home Situations Questionnaire (HSQ) contains 25 items focused on noncompliant behavior (Barkley and Murphy 1998). The instructions ask the parent to consider “how well your child follows instructions or rules in a variety of settings.” For example, “getting dressed,” “while you are on the telephone,” “when asked to do chores.” Questions answered affirmatively are then rated on a one to nine Likert scale with higher scores indicating greater noncompliance. The HSQ yields two scores: a count of “yes” responses (0–25) and a severity score (total of 1–9 ratings on “yes” items; range = 0–225). This severity score is divided by 25 to obtain a per item mean score. The HSQ has been used in trials involving children with ADHD (Abikoff et al. 2004). To ensure relevance for children with PDD, we added items that are more appropriate for this population. For example, “when asked to move from one activity to another,” “when repetitive behavior is interrupted.” The correlation of the mean HSQ score and ABC Irritability score for the 124 study subjects at baseline was 0.30 (P < 0.001) suggesting that these ratings are measuring separate domains of behavior.

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Vineland)

The Vineland assesses adaptive functioning across socialization, communication, and daily living skill domains. The Vineland relies on an informant (mother or primary caretaker) to describe what the child typically does in the course of daily living—not what the child can do in optimal conditions (Sparrow et al. 1984). As with intelligence tests, the Vineland has been standardized with a mean of 100 ± 15 points. Children with mental retardation only show Vineland scores that are consistent with their IQ (e.g., IQ of 60 and Vineland scores around 60) (Sparrow et al. 1984). Children with PDD, however, consistently have Vineland scores that are full standard deviation or more below their IQ score (Carter et al. 1998; Kraijer 2000). In the daily living skills domain, noncompliance, tantrums and aggression may interfere with the child's acquisition and regular performance of already attained skills. We predicted that the additive effects of PT would promote improvement in Age Equivalent and raw scores on the Vineland through the reduction of noncompliant behavior.

Side Effects Review Form

Side Effects Review Form (SERF) is a 32-item parent interview covering the child's health problems, recent medical consultations, and concomitant medications as well as appetite, sleep, activity level, gastrointestinal and urinary function, and relevant neurological symptoms (RUPP Autism Network 2002). It was administered at baseline and at every visit throughout the trial. In addition, vital signs, body weight and routine laboratory indices were monitored throughout the study. Adverse events were documented according to start date, severity (Mild, Moderate, Severe), potential relatedness to the study drug, and date of offset.

Interventions

Risperidone Dose Schedule

Children between 14 and 20 kg started with 0.25 mg at night followed by 0.25 twice a day on day 4; children over 20 kg started on 0.5 mg. As in our previous study (RUPP Autism Network 2002), the dose was gradually increased over a 4-week period as tolerated to a maximum of 2.5 mg/day for smaller children (<45 kg) and up to 3.5 mg/day for larger children (≥45 kg). This dose schedule served as a guide; treating clinicians could delay an increase or reduce the dose to manage adverse effects in the dose adjustment phase. If the maximum dose was not reached during the first 4 weeks, the treating clinician could elect to increase the dose after week 8.

Dose Reduction in the Discontinuation Phase

Following the classification of positive response at week 24 and a separate informed consent procedure, children were eligible to enter the Discontinuation phase. The medication was reduced to 75% of the maintenance dose for week 25; to 50% for weeks 26 through 29; to 25% for week 30, and to 0 for weeks 31 through 34. Subjects were monitored weekly for signs of relapse (i.e., 25% increase in the ABC Irritability subscale and a score of Much Worse or Very Much Worse on the CGI-I). The rationale for the 4-week observation on 50% of the maintenance dose was to evaluate whether some subjects could be maintained at this lower dose level—even if subsequent dose reduction resulted in relapse.

Use of Aripiprazole (Management of Attrition)

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the benefits of medication alone versus medication plus PT at week 24. Therefore, attrition early in the trial would be undesirable. In the previous risperidone trial approximately 30% of the subjects did not show a positive response to risperidone (RUPP Autism Network 2002). In the current study, this would translate into an estimated attrition of 12 subjects in the drug only group (30% of 40) and 24 subjects in the combined treatment group (30% of 80 subjects). In order to protect against attrition, we offered treatment with aripiprazole to subjects who did not show a positive response to risperidone in the first 8 weeks. In the data analysis, these subjects remained in their randomized group (i.e., medication only or medication + PT).

Aripiprazole is a novel antipsychotic that acts as a partial dopamine and serotonin agonist. Aripiprazole is believed to exert an anti-dopaminergic effect under conditions of dopamine excess and dopamine enhancing effects in the context of reduced synaptic dopamine. By contrast, risperidone is a potent post-synaptic dopamine antagonist; a property it shares with haloperidol. Although haloperidol has been shown to be effective for serious behavioral problems in autism, it has many well-documented drawbacks (Campbell et al. 1997). Thus, it was not considered an acceptable alternative for subjects who failed treatment with risperidone in this study. In addition, the preliminary results for olanzapine, quetiapine or ziprasidone were not persuasive (Scahill and Martin 2005). Studies in adults with schizophrenia show that aripiprazole is an effective antipsychotic with a low risk of neurological effects, weight gain and hyperprolactinemia (Kane et al. 2002). Given that aripiprazole has features in common with risperidone, but has unique properties that make it fundamentally different, we concluded that it might be effective when risperidone is not. To date, there are few published reports on the use of aripiprazole in children with autism. The few case available case reports suggest that aripiprazole is generally well-tolerated (McDougle et al. 2008). As shown in Table 3, we started with a low dose and moved up gradually. During the medication switch, subjects were seen weekly. For subjects in the combined treatment group, the PT program continued during and after the switch to aripiprazole.

Table 3.

Schedule for switching subjects from risperidone to aripiprazole

| Risperidone | Aripiprazolec |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| >25 kg | ≤25 kg | ||

| Day 57 (week 8)a | 75% of doseb | 2.5 mg | 2.5 |

| Day 61 | 5.0 mg | (no increase) | |

| Day 64 (week 9) | 50% of dose | 7.5 mg | 5.0 |

| Day 71 (week 10) | 25% of dose | 10 mg | 7.5 |

| Day 78 (week 11) | Stop | 12.5 mg | 10 |

| Day 85 (week 12) | 15 mg | 12.5 | |

| Day 92 (week 13)d | 20 mgd | 15 | |

Switch could occur as early as week 4

Evening dose decreased first; subsequent decreases were made one day after the study visit

Aripiprazole started in the morning; could switch to bedtime to manage sedation. The upward adjustment could be delayed to manage adverse effects. The dose could be decreased at any time to manage adverse effects

This dose increase was optional in case of incomplete response and the increase may be a similar increment if all prior increases were not made

Parent Training

Parent training (PT) is an empirically supported intervention for typically developing children with disruptive behavior (Kazdin and Weisz 2003). In children with autism, parent training has incorporated techniques of ABA to meet the needs of developmentally disabled children. As noted above, most of the research on ABA has employed single-subject designs and dissemination of exportable parent training programs has been inadequate (Smith et al. 2007). To conduct this trial, we developed a treatment manual and conducted a pilot trial to ensure that it would be acceptable to parents and could be delivered reliably by therapists in a multisite trial (Johnson et al. 2007). Another important goal in the development of our PT program was that it be exportable and affordable. To these ends, we built a PT program of intermediate intensity that can be delivered in 14–16 outpatient sessions and two home visits over a period of 16–24 weeks. By contrast, ABA programs recommend 40 hours per week for up to 2 years (reviewed in Smith et al. 2007; Johnson et al. 2007).

In our pilot study with our PT manual involving 17 families, parents attended 93% of sessions and indices of parental adherence to the protocol exceeded 80% (RUPP Autism Network 2007). Methods used to train therapists and monitor treatment fidelity over time were effective and showed 90% reliability in the delivery of the treatment. There was a 39% improvement on the HSQ per item mean score (from 3.6 (±1.1) to 2.2 (±1.5); effect size = 1.3). The average age of the sample was 7.7 ± 2.6 years at baseline; the average Age Equivalent score on the Vineland Daily Living Skills domain was 35 months. After 6 months of PT, there was a 7-month gain in the Vineland Age Equivalent score (effect size = 0.37) or 1 month greater than the passage of time (RUPP Autism Network 2007).

The 24-week PT program consists of 11 core sessions and 3–5 optional sessions delivered individually to a parent (or primary caretaker). Each session is approximately 90 min in duration. Sessions employed direct instruction, in-session practice activities, review of video vignettes, and role-playing. The manual provides scripts for the therapists, handouts for parents, and weekly homework assignments. These homework assignments include data collection on the child's behavior and application of parenting techniques presented in PT sessions (see Johnson et al. 2007 for a detailed description).

In the behavioral analysis of aggression, tantrums and self-injury, the clinician tries to isolate the function of the child's behavior. For example, a child who explodes when asked to perform activities of daily living or to incorporate new skills may learn that tantrums result in escape from parental demand. Thus, early PT sessions focus on analysis of behavior with special attention to the function of maladaptive behavior through identification of antecedents and consequences of behavior. The child who has a tantrum when prompted to get dressed may escape the demand as the mother feels she has no alternative but dress the child herself. In this simplified example, the antecedent is the routine demand of getting dressed, the consequence is escaping the demand. Escaping the demand reinforces the tantrum. The core modules that focus on reinforcement principles, compliance training and functional communication address the tantrums. The therapist could also bring in one of several optional sessions such as time out, contingency contracting, or crisis management as appropriate. The final set of core sessions includes teaching parents to promote skill acquisition and to consolidate behavioral change. Three planned booster sessions can be used to review specific sessions or to introduce one of the optional modules.

Behavior therapists also conducted two home visits: one early in the treatment program and one toward the end of the treatment program. The purposes of the home visits were to observe parent-child interaction early in treatment and to provide in vivo review of techniques taught in the PT program.

Data Analytic Plan

First Set of Analyses

The characteristics of the randomly assigned treatment groups will be examined to check for differences at baseline. Using the intent-to-treat convention, all randomized subjects will be included in the analyses. Given that tantrums, aggression and self-injury are the behaviors that brought the child into the study, we will examine the change in the ABC Irritability subscale from baseline to week 8 and from baseline to week 24 across treatment groups. These analyses will be done with random regression in which each subject's response during the trial is modeled against time to show the downward slope of the Irritability scale over time (Gibbons et al. 1993). Although we expect to see improvement on the ABC Irritability score in both groups, we will compare the average slope of the regression line across the two groups to test whether the combined treatment group is superior to the medication-only group. The proportion of overall positive response in each group as evidenced by ratings of Much Improved or Very Much Improved will be compared at week 8 and 24 by chi square analyses. In keeping with the model that the differential effects for combined treatment versus medication only on noncompliance (as measured on the HSQ) and adaptive functioning (Daily Living Scale of the Vineland), the analyses of the ABC Irritability scale and the CGI-I are essential—but are not primary outcomes.

Primary Hypotheses

We predict that after 24 weeks of treatment, medication + PT will be more effective than medication alone in reducing noncompliant behavior and improving adaptive behavior in children with PDD accompanied by tantrums, aggression, and self-injury. The HSQ is the first primary outcome measure because we assume it will change before adaptive functioning (measured at week 16 and 24 on the Vineland Daily Living). In our pilot PT study, the effect size on the HSQ was 1.3 (from 3.6 ± 1.1 to 2.2 ± 1.5). Unlike the pilot study, which enrolled children on stable doses of medication, this trial selected medication-free children with untreated serious behavioral problems. Thus, we anticipated higher HSQ scores at baseline in the randomized trial. To estimate sample size, we presumed baseline HSQ scores of 4.0 ± 1.4 for both groups, a 25% improvement for the medication only group (1 point drop) and a 50% improvement for the combined treatment group (2 point drop). This translates into a plausible and clinically meaningful effect size of 0.7 (change of 2 points for combined treatment—one point for drug only divided by 1.4 = 0.7). The planned sample of 80 subjects in combined treatment and 40 subjects in the medication only group is large enough to detect an effect size of approximately 0.60 with 80% power with alpha set at 0.05 (Borenstein et al. 1997). Given that the HSQ was collected repeatedly during the trial, the change in the HSQ will be analyzed by random regression, which will increase statistical power to detect a difference between groups than the more conservative pre- and post-treatment comparison across groups.

The second primary outcome measure is the Age Equivalent score on the Vineland Daily Living Skills domain. Change in Age Equivalent score will be compared across the two groups from baseline to week 24 by ANCOVA. To minimize missing data during the trial, we planned an early endpoint assessment for subjects who dropped out prematurely in order to carry that score forward to week 24. Given the hierarchical approach to analysis, we set the alpha level at 0.05 for evaluating the response on the HSQ. If change in the HSQ is significantly different across the two groups, we will proceed with an alpha of 0.05 for the analysis of the Vineland. If the analysis of the HSQ is not significant at the 0.05 level, the alpha level will be reset to 0.025 for the Vineland analysis. The other Vineland Adaptive Behavior scales will be examined in exploratory analyses without correction for multiple comparisons.

Exploratory Analyses

The model proposed in this study implies that medication plus PT will promote greater gains in noncompliance leading to improved adaptive functioning. In this model, the improvement in noncompliance is a prerequisite, or a mediator, for improvement in adaptive functioning (Shrout and Bolger 2002). First, we will examine the change in noncompliance on the HSQ from baseline to week 16 across treatment groups. week 16 is selected as a nodal point because it is the first post-baseline administration of the Vineland daily living skills. We will then examine whether there are further improvements in adaptive functioning from week 16 through 24. Incremental improvement in noncompliance and adaptive functioning suggests that improvement in daily living skills depends, at least in part, on change in noncompliance. We will also explore predictors of gains in adaptive behavior with logistic regression models. As noted above, children with PDD consistently often have lower adaptive function that their IQ scores would predict. Indeed, many lose ground in adaptive functioning over time. The logistic regression models will evaluate the impact of PT and subject characteristics on the likelihood of achieving gains in Age Equivalent scores on the Vineland from baseline to week 24 that are consistent with the passage of time.

Analytic Strategies for the Discontinuation Phase (Primary Hypothesis)

We predicted that the medication alone group would show a higher percentage of relapse than the combined treatment group during the Discontinuation phase. Although the current study did not employ placebo-control, subjects were assessed by the independent evaluator, who was unaware of the original treatment assignment (medication only or medication plus PT).

The relapse rate was 62.5% in the group assigned to placebo in our previous discontinuation study (RUPP Autism Network 2005b). Assuming a similar relapse rate for the medication only group in the current study, the relapse rate in the combined treatment group would have to be 30–40% lower to show a significant difference from the medication only group. Given this relatively large difference, the relapse rate for each group was monitored by an external board. If, upon external review, it became clear that detecting a difference in the relapse rate would be statistically impossible or if the relapse rate was dramatically different across the two groups, this phase would be halted.

Exploratory Analyses

Even if there is not a statistically different relapse rate between the two groups, however, we plan to conduct several other exploratory analyses. Using survival analysis, we can evaluate whether PT had a protective effect against relapse by calculating the time to relapse in each group. If so, it might suggest that children receiving combined treatment could be managed on lower doses of the medication. To take advantage of the full duration of the trial, we will examine all “treatment failures” (i.e., subjects who do not meet positive response criteria at week 8, subjects who showed a return of target symptoms between week 8 and 24 or during the Discontinuation phase). The time to “treatment failure” within each group will be compared with a proportional hazard model.

Discussion

Studies designed to compare medication to combined treatment with medication and a psychosocial intervention are becoming more common in child mental health (e.g., MTA Cooperative Group 1999; TADS Team 2004; Abikoff et al. 2004; POTS 2004). To date, studies of combined treatments in child psychiatry have directed both treatments at the same outcome (e.g., ADHD symptoms in MTA and depression in TADS). If the drug treatment (e.g., stimulant in MTA) has a large effect, it may be difficult to show an additive effect of the psychosocial intervention simply because there is little or no room for improvement on the primary outcome measure. Thus, a fundamental design question for this study was whether medication and PT should be directed at the same (tantrums, aggression, self-injury) or separate outcomes. The clear superiority of risperidone over placebo in our previous study obviated the need for a placebo group on scientific and ethical grounds (Scahill et al. 2008). Furthermore, the large effect of risperidone on tantrums, aggression and self-injury in our prior study also argued against choosing serious behavioral problems as the primary outcome. The large effect of risperidone also challenged the inclusion of a PT only comparison group. The two-group trial also provided greater statistical power in a sample of 124 subjects than a three or four-group trial.

Despite the significant and enduring reduction in serious behavioral problems with risperidone over 6 months, however, we observed only modest improvements on measures of adaptive functioning (daily living skills, socialization and communication) after 6 months of treatment in our prior trial (Williams et al. 2006). Thus, we proposed a model in which noncompliance and serious behavioral problems interfere with the acquisition of new adaptive skills and the regular performance of already acquired skills. Medication plays a necessary role by reducing the serious behavioral problems (tantrums, aggression and self-injury) and sets the stage for the success of PT. We predicted that, compared to medication alone, medication plus PT will be associated with significantly greater improvement in noncompliance as measured by the HSQ and enhance adaptive functioning as measured on the Vineland. This study offers an approach to the study of combining medication and behavioral intervention in which treatments are not directed at the same outcome. It also offers clinicians and families a way of conceptualizing the purpose of medication and parent training in this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the following cooperative agreement grants from the National Institute of Mental Health: U10MH66768 (P.I., M. Aman), U10MH66766 (P.I., C. McDougle), and U10MH66764 (P.I., L. Scahill). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, or any other part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors would like to acknowledge the following people: Stacie Trollinger, Patricia Shugarts, Allison Gavaletz, Kristy Hall, Arlene Kohn, Kathy Koenig, MSN, Maryellen Pachler, MSN, Sue Thompson, MSN, Roumen Niklov, MD, Kristina Siefker, MS, Mariana Zaphiriou, Erin Kustan, Scientific Advisors, Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Footnotes

From the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network.

Disclosure Dr. Scahill consults to Janssen Pharmaceutica, Supernus and Bristol-Myers Squibb, Neuropharm, Shire. Dr. Aman consults to Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly, Forest Labs and Abbott. Dr. Arnold consults to Eli Lilly, McNeil, Novartis, Noven, Shire, Sigma Tau and Targacept. Dr. McDougle consults to Forest Research Institute, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica. Dr. McCracken consults to Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly, Abbott, Bristol Myers Squibb, Shire, Wyeth, Pfizer, Cephalon, and McNeil. Dr. Handen consults to Bristol Myers Squibb, Forest Labs, Pfizer. The other authors have no financial relationships with for-profit enterprises to disclose.

Contributor Information

Lawrence Scahill, .

Michael G. Aman,

Christopher J. McDougle,

L. Eugene Arnold, .

James T. McCracken,

Benjamin Handen, .

Cynthia Johnson, .

James Dziura, .

Eric Butter, .

Denis Sukhodolsky, .

Naomi Swiezy, .

James Mulick, .

Kimberly Stigler, .

Karen Bearss, .

Louise Ritz, .

Ann Wagner, .

Benedetto Vitiello, .

References

- Abikoff H, Hechtman L, Klein RG, Weiss G, Fleiss K, Etcovitch J, et al. Symptomatic improvement in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:802–811. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128791.10014.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1985;89:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Turbott SH. Reliability of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the effect of variations in instructions. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1987;92:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Rothman H, Cohen J. Power and precision program. Erlbaum; New Jersey: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC, Aman MG, Havercamp SM. Factor analysis and norms for parent ratings on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-community for young people in special education. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2002;23:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(01)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Armenteros JL, Malone RP, Adams PB, Eisenberg ZW, Overall JE. Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in autistic children: a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:835–843. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Wang JJ, Lord C, Dawson G, et al. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Supplementary norms for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28:287–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1026056518470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Educating children with autism. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. The prevalence of autism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:87–89. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Devincent CJ, Pomeroy J, Azizian A. Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-age children with PDD versus clinic and community samples. Autism. 2005;9(4):392–415. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, et al. Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data. Application to the NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program dataset. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:739–750. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210073009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. DHEW, NIMH.; Washington, DC: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Phillips A, Chaplin W, Zagursky K, Novotny S, Wasserman S, et al. A placebo controlled crossover trial of liquid fluoxetine on repetitive behaviors in childhood and adolescent autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:582–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CR, Handen BL, Butter E, Wagner A, Mulick J, Sukhodolsky DG, et al. Development of a parent training program for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Behavioral Interventions. 2007;22:201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, McQuade RD, Ingenito GG, Zimbroff DL, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:763–771. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kraijer D. Review of adaptive behavior studies in mentally retarded persons with autism/pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:39–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1005460027636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Wagner A, Rogers S, Szatmari P, Aman M, Charman T, et al. Challenges in evaluating psychosocial interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:695–708. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0017-6. discussion 709–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas OI. Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:3–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Aman MG, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Davies M, et al. Risperidone for the core symptom domains of autism: results from the study by the autism network of the research units on pediatric psychopharmacology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1142–1148. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, Posey DJ. Atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 4):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group Multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network Risperidone in children with autism for serious behavioral problems. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:314–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: Longer term benefits and blinded discontinuation after six months. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005b;162:1361–1369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network Parent training for children with pervasive developmental disorders: A multi-site feasibility trial. Behavioral Interventions. 2007;22:179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Martin A. Psychopharmacology. In: Volkmar F, Klin A, Paul R, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. 3rd ed. Wiley; New York: 2005. pp. 1102–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Solanto M, McGuire J. The science and ethics of placebo in pediatric psychopharmacology. Ethics and Behavior. 2008;18:266–285. [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L. Intensive behavioral/psychoeducational treatments for autism: Research needs and future directions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:373–378. doi: 10.1023/a:1005535120023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):634–641. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0264-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Buch GA, Gamby TE. Parent-directed, intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Scahill L, Dawson G, Guthrie D, Lord C, Odom S, et al. Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:354–366. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior scales: Survey form manual. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SK, Scahill L, Vitiello B, Aman MG, Arnold LE, McDougle CJ, et al. Risperidone and adaptive behavior in children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:431–439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000196423.80717.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]