A person’s sense of mastery is an important predictor of their physical and mental health. Mastery is the extent to which individuals perceive that they influence their life chances. Mastery is beneficial in two ways: those with a higher sense of mastery appraise stressors as less detrimental, making stressors less harmful, and are better able to overcome stressors by using mastery as a coping resource (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Life experiences and position in the social structure shape each individual’s sense of mastery; the stress process model posits that exposure to stressors explains the relationship between social and economic disadvantage and poorer mental health. Exposure to stressors is associated with lower mastery, which in turn is associated with poorer mental and physical health (Thoits, 1995).

Both individual and neighborhood disadvantage contributes to exposure to stressors. Aneshensel (2010) expanded Pearlin and colleagues’ (1981) stress process model to the neighborhood level. Empirical evidence of an association of neighborhood stressors with mental health supports this model (e.g., Echeverría et al. 2008; Kim 2008; Mair et al. 2008). The ecological stress process model identifies mastery as an important pathway from neighborhood stressors to mental health (Aneshensel, 2010). Furthermore, it suggests that the social and economic status of residents may affect the extent to which neighborhood stressors impact mental health and coping resources such as mastery.

Evidence suggests that race and ethnicity predict neighborhood status and exposure to neighborhood stressors. Blacks experience neighborhood disadvantage and downward mobility into disadvantaged neighborhoods at higher rates than Whites of comparable income and education levels (Sharkey, 2008). In racially mixed, Latino, and Black neighborhoods, neighborhood poverty is significantly associated with neighborhood disorder, an important stressor (Sampson, 2009). Blacks not only disproportionately experience neighborhood stressors, but also have fewer opportunities to escape stressful neighborhoods than Whites (Morenoff & Sampson, 1997; South & Deane, 1993).

Building on this evidence, this paper examines racial and ethnic differences in how neighborhood stressors relate to mastery. I suggest that a compound disadvantage model predicts more detrimental effects of neighborhood stressors on mastery for racial and ethnic minorities than Whites, a hypothesis I test by examining cross-level interactions in a multilevel model in a sample of residents of Chicago, Illinois. This paper contributes to the literature on the stress process in general and the neighborhood stress process in particular. Results suggest racial and ethnic heterogeneity in the effect of neighborhood context supporting compound disadvantage.

Neighborhood Compound Disadvantage

Stress process theory suggests that the effects of stressors may differ for individuals of different social or economic status groups. Two moderation models have been proposed: compound disadvantage and compound advantage (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). In the case of neighborhood stressors, the compound disadvantage model suggests that neighborhood stressors have larger, more detrimental effects for those from disadvantaged social and economic groups. Compound advantage, on the other hand, suggests that neighborhood stressors are less psychologically harmful for those from disadvantaged groups (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). I suggest that neighborhood stressors are a source of compound disadvantage for racial and ethnic minority groups for whom segregation limits the extent to which they can avoid neighborhood stressors.

Neighborhood stressors, which include increasing violence, crime, and social disorder, do not occur randomly throughout a city; rather they are concentrated in poorer, non-White neighborhoods. Because Blacks and Latinos are more likely to live in poor, non-White neighborhoods (Massey, 2004), they are also more likely to live in high stressor neighborhoods. In Chicago’s non-white neighborhoods, neighborhood poverty is significantly associated with neighborhood disorder (Sampson, 2009). Furthermore, it is harder for racial and ethnic minorities to leave segregated neighborhoods. Evidence suggests that, in Chicago, Blacks have not been able to move out of high crime neighborhoods. Increasing crime in and near a neighborhood is associated with Black population gain and White population loss in Chicago (Morenoff & Sampson, 1997). If Black and Hispanic residents of stressful neighborhoods have limited opportunities to move out of those neighborhoods, neighborhood stressors may diminish their sense of mastery at a greater magnitude than they do Whites’, who may perceive better opportunities to move. This hypothesized moderating effect is consistent with the compound disadvantage model (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). Several empirical studies of neighborhood- and individual-level socioeconomic status have supported compound disadvantage (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003; Wight, Ko, & Aneshensel, 2011, Schieman, Pearlin, & Meerson, 2006). Some research has examined moderation of neighborhood stressors by race and ethnicity for mental health (especially depression and anxiety). This evidence is mixed, finding evidence of compound disadvantage for Hispanics but no difference between Blacks and Whites when measuring neighborhood stressors as subjective, individual-level perceptions of the neighborhood (Hill & Maimon, 2013). Compound disadvantage was not found by race or ethnicity when the effects of neighborhood-level stressors on depressive symptoms were examined using the current data (Gilster, 2014). Mental health may be not capture compound disadvantage between race and ethnicity and neighborhood stressors because racial and ethnic disparities in mental health, especially depression and anxiety examined in the above studies, are less prevalent than physical health disparities (Kessler et al., 1994). No studies have examined neighborhood compound disadvantage and mastery.

Neighborhood Stressors and Mastery

As stress process theory suggests, mastery is important for individual well-being. Research of mastery and similar constructs such as personal control (Mirowsky & Ross, 1989) and internal locus of control (Rotter, 1966) illuminates this importance. Research suggests that mastery is associated with better mental and physical health (e.g., Jang Borenstein-Graves, Haley, Small, & Mortimer, 2005, Kiecolt, Hughes, & Keith, 2009; Lachman &Weaver, 1998; Pearlin, et al., 1981; Ross, Mirowsky, & Pribesh, 2001; Thoits, 2010).

Stress process theory also posits that members of disadvantaged groups have less mastery (Pearlin, et al., 1981). Most empirical evidence supports this claim for disadvantaged racial group status. Researchers have found African Americans have lower levels of mastery than Whites in bivariate analyses (Jang et al. 2003; Christie-Mizell & Erickson 2007) and when controlling for sociodemographic characteristics (Jang et al. 2003; Bruce & Thornton, 2004), although one study found no differences with similar controls (e.g., Christie-Mizell & Erickson 2007). Keith et al. (2010) found an association between experiences of racial discrimination and lower mastery among African Americans. Bruce and Thornton (2004) found significant differences between Blacks and Whites across both social and economic predictors of mastery; for example their study showed social support is a significant predictor of higher mastery for White men, White women, and Black men, but not Black women. Fewer researchers have compared Latinos and Whites with respect to mastery; Christie-Mizell and Erickson (2007) found that Latino mastery rates were not significantly different from Whites’, but Heller et al. (2004) found a negative association between mastery and Mexican ethnicity and cultural identification.

Minimal research has addressed whether neighborhood stressors affect mastery in different ways among racial and ethnic groups. Schwartz and Meyer (2010) have recently criticized the literature testing the stress process because of researchers’ reliance on within-group analyses in relatively homogenous samples. In one exception, Kim and Conley (2011) found a stronger association between perception of neighborhood disorder and sense of personal control for Whites than non-Whites in a sample of English-speaking adults in Illinois. While these findings do not support the compound disadvantage model I propose here, Kim and Conley conceptualize neighborhood disorder as an individual perception rather than a neighborhood characteristic.

Research on the stress process most often uses individual perceptions to measure neighborhood stressors; these studies have found perceptions of stressors are associated with lower mastery (Christie-Mizell & Erickson, 2007; Geis & Ross, 1998). While an individual-level measure may help explain proximal processes, the respondent’s psychological well being may bias the measure. That is, because those with higher mastery appraise situations as less stressful, they may perceive less social disorder in their neighborhoods than others may. Neighborhood-level measures, such as aggregate resident perception and objective assessments, avoid this same source bias (Raudenbush & Sampson, 1999). Individual-level measures may capture an individual’s experience of a neighborhood (Hill& Maimon, 2013) and exposure to neighborhood stressors rather than a characteristic of the neighborhood. This research employs both aggregate perceptions and objective assessments to measure neighborhood stressors.

In summary, this research seeks to understand a component of the stress process by investigating the relationship between neighborhood stressors and mastery. It seeks to address a gap in the research by examining the relationship between perceived and objective neighborhood-level measures of stressors and mastery. It also tests a compound disadvantage model to examine group-specific relationships between neighborhood stressors and mastery. Comparing non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic adults, it examines the hypothesis that neighborhood stressors will be more negatively associated with mastery for Blacks and Hispanics than for Whites.

METHODS

Data

This study employs data from the Chicago Community Adult Health Study (CCAHS), which surveyed 3,105 adults from a neighborhood-stratified, multistage probability sample of Chicago residents (Morenoff et al., 2008). The research team conducted face-to-face survey interviews between 2001 and 2003 with one adult from each sampled home. The response rate was 72%. Questions addressed mental and physical well-being, activities, and neighborhood perceptions. Neighborhoods were operationalized as neighborhood clusters, aggregations of contiguous census tracts that the 1995 Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (e.g., Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). The sample included between 1 and 21 respondents from all 343 Chicago neighborhood clusters, with an average of 9.06 respondents per cluster. CCAHS data collection also included systematic social observations (SSO) of the physical and social characteristics of neighborhoods (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). This study also used data on crime from the Uniform Crime Reports and data on housing characteristics from the 2000 US Census.

Previous research using CCAHS data has found that neighborhood context is related to health (e.g., King et al., 2011; Morenoff et al., 2008), mental health (e.g., Mair et al., 2008; Glister, 2014a), and community engagement (e.g., Gilster, 2014b). Furthermore, accounting for neighborhood context explained racial disparities in health (e.g., King et al.; Morenoff et al.).

Measures

Neighborhood level measures

The measure of perceived neighborhood stressors captured resident perceptions of the neighborhood social and physical environment that make the neighborhood difficult to live in. Four scales, identified in a factor analysis of neighborhood-level measures of the physical and social environment of Chicago neighborhoods, make up the measure of perceived neighborhood stressors: a) neighborhood disorder, b) perceived neighborhood violence, c) neighborhood hazards, and d) neighborhood services (reverse coded). These scales are detailed in Appendix B. Each of the component scales was derived by aggregating individual scales to the neighborhood level using empirical Bayes estimation (Mujahid et al., 2007). The final variable was created by standardizing and averaging the component scales. The measure was highly consistent, with a neighborhood-level alpha of .91. Higher scores indicate more stressors in the neighborhood

The measure of observed neighborhood stressors captured objective assessments of the neighborhood social and physical environment from administrative data and trained observer ratings. The same factor analysis that identified the components of the perceived neighborhood stressors provided the components: Uniform Crime Report data on rates of homicide, robbery, and burglary; SSO data on the proportion of blocks with deterioration and vacant lots and aggregated rating scales of disorder and street conditions; and US Census data on percent of vacant housing. The final variable is an average of all component measures standardized as Z scores, with an alpha value of .89.

Perceived and observed neighborhood stressors have a neighborhood-level correlation of .71 (p<.001, n=343). Neighborhood measures were therefore tested individually in order to see whether each has a relationship to mastery. Next, measures were examined together to see which remained a more important predictor.

Individual level measures

Four items from the Pearlin Mastery scale comprise the measure of mastery (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Respondents responded to statements with four response options ranging from agree strongly to disagree strongly. Items were scored such that higher values indicate more mastery. The mastery scale had a Chronbach’s alpha of .83 for this sample. The scale was constructed from the mean of all items with responses with a possible (range of 1 to 4); 18 respondents had fewer than five responses. Two respondents had no responses to any questions on the scale, and the scales for these respondents were imputed using OLS with age, sex, education, income, race, Hispanic ethnicity, immigration status, marital status, home ownership, and other psychological resources as predictors.

Respondent race and ethnicity was ascertained by first asking if the respondent identified as Hispanic or Latino and then asking respondents to choose one or more races: White/Caucasian, Black/African American, American Indian, Asian, Pacific Islander, other race. The Hispanic category is comprised of Hispanics and Latinos of any race. Due to a small sample sizes, American Indian, Asian, Pacific Islander, and other race, if not also Hispanic, were all grouped into the “other non-Hispanic” category. Interpretation and discussion of results does not focus on this heterogeneous group.

Interviewer observation supplied respondent gender. All other individual-level demographic variables come from respondent responses. Responses to the question “Are you working now for pay, looking for work, retired, keeping house, a student, or something else?” provided employment status. Those who responded with “something else” were all recoded into the first five categories based on their open-ended explanation. Four categories indicate years of education: less than a high school education (<12 years), a high school diploma (12 years), some college (13–15 years), and a college diploma or beyond (≥16 years). Marital status categories are married, separated, divorced, widowed, and never married. Income is measured by a categorical variable with five income categories. Four categories of income (less than $5,000; $5,000–14,999; $15,000–39,999; and $40,000 or more) and, because many individuals (n=577) were missing on income, another category identifying those with missing income data. Age is a categorical variable with six categories (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and 70 or older). Respondents were asked about their length of residence at their current address. Residential stability is a dichotomous variable; respondents reported whether they lived at their current address for five or more years.

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 describes the sample for this study as well as the composition of the sample with survey weights applied. The sample is diverse in race and ethnicity, making it a strong sample to examine questions of racial and ethnic variation in the relationship of neighborhood stressors to mastery. The sample is also diverse in educational background. Neighborhood stressors are measured by neighborhood-level continuous variables. Neighborhood perceived stressors have a weighted mean of −0.18 and observed stressors have a weighted mean of −0.17.

Table 1.

Individual level descriptive statistics for survey respondents and the sample with survey weights applied (N=3105).

| Respondent Sample | Weighted Sample |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | |

| Race and Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 983 | 31.66 | 38.36 |

| Hispanic | 802 | 25.83 | 25.81 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1240 | 39.94 | 32.07 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 80 | 2.58 | 3.77 |

| First Generation Immigrant | 773 | 24.90 | 26.89 |

| Female | 1870 | 60.23 | 52.62 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1,954 | 62.93 | 64.36 |

| Unemployed | 297 | 9.57 | 8.75 |

| Retired | 491 | 15.81 | 15.71 |

| Home caregiver | 268 | 8.63 | 7.83 |

| Student | 95 | 3.06 | 3.36 |

| Education | |||

| Less than 12 years | 792 | 25.51 | 23.42 |

| 12 years | 759 | 24.44 | 23.75 |

| 13–15 years | 817 | 26.31 | 24.95 |

| 16+ years | 737 | 23.74 | 27.90 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 1,091 | 35.14 | 41.81 |

| Separated | 171 | 5.51 | 4.02 |

| Divorced | 414 | 13.33 | 10.76 |

| Widowed | 256 | 8.24 | 6.72 |

| Never married | 1,173 | 37.78 | 36.69 |

| Annual Income | |||

| Less than 5, 000 | 185 | 5.96 | 5.17 |

| 5,000 to 15,000 | 501 | 16.14 | 14.94 |

| 15,000 to 40,000 | 984 | 28.79 | 26.44 |

| More than 40,000 | 948 | 30.53 | 34.84 |

| Missing | 577 | 18.58 | 18.60 |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 800 | 25.76 | 27.51 |

| 30–39 | 748 | 24.09 | 22.69 |

| 40–49 | 608 | 19.58 | 18.74 |

| 50–59 | 402 | 12.95 | 12.90 |

| 60–69 | 286 | 9.21 | 8.98 |

| 70+ | 261 | 8.41 | 9.19 |

| Residential Stability (5+ years) | 1255 | 40.42 | 41.11 |

Analyses

I ran models with race and ethnicity to understand disparities in mastery first. Then, I examined how controlling for sociodemographic and neighborhood characteristics changes disparities. Finally, I examined interactions of race and ethnicity with neighborhood stressors. The data were grouped by neighborhood cluster, which means that individual observations violate independence at the neighborhood-cluster level. The analysis was therefore conducted using multilevel modeling in HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004). Survey weights were used so that the sample is representative of the population of Chicago (see Morenoff et al., 2008). Descriptive analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp, 2009).

RESULTS

I conducted weighted bivariate regression analyses to examine the relationship between neighborhood stressors and resident race and ethnicity. The limits to analyses available with survey weights in Stata dictated the selection of regression analysis. Results reveal that Hispanic and Black respondents live in neighborhoods characterized by significantly more perceived and observed neighborhood stressors than Whites, as expected.

In a null model predicting mastery scores, there was significant variation in mastery across neighborhood clusters (τ=0.032, p<.001). The interclass correlation (ICC) was .057, which falls within the moderate range (Hox, 1996). This ICC indicates that 5.7 percent of the variance in mastery is attributable to the neighborhood-cluster-level.

Table 1 presents results from multivariate multilevel regression models predicting mastery scores. Model 1 details the relationship of race and ethnicity alone to mastery. Hispanic respondents had lower mastery than Whites. Black respondents have lower mastery than Whites, but not significantly lower. However, the inclusion of sociodemographic data in Model 2 explains the negative association of Hispanic ethnicity and makes the association of Black ethnicity with mastery positive and significant. That is, Blacks have higher mastery scores than Whites controlling for differences in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Including neighborhood-level stressors, in Model 3, makes this mastery advantage for Blacks even greater. Including perceived and observed neighborhood stressors reveals a smaller, marginally significant advantage of Hispanic ethnicity (b=.073, p<.10). These models are consistent with the finding in the extant literature that sociodemographic characteristics account for racial and ethnic group differences in mastery.

When entered individually (in models not shown here), higher levels of both perceived and observed neighborhood stressors are both significantly associated with lower levels of mastery. When both neighborhood-level measures of stressors are included in the same model (Model 3), observed neighborhood stressors are no longer significantly associated with mastery. Perceived neighborhood stressors remains statistically significant. Perceived neighborhood stressors mediate the effect of observed neighborhood stressors on mastery.

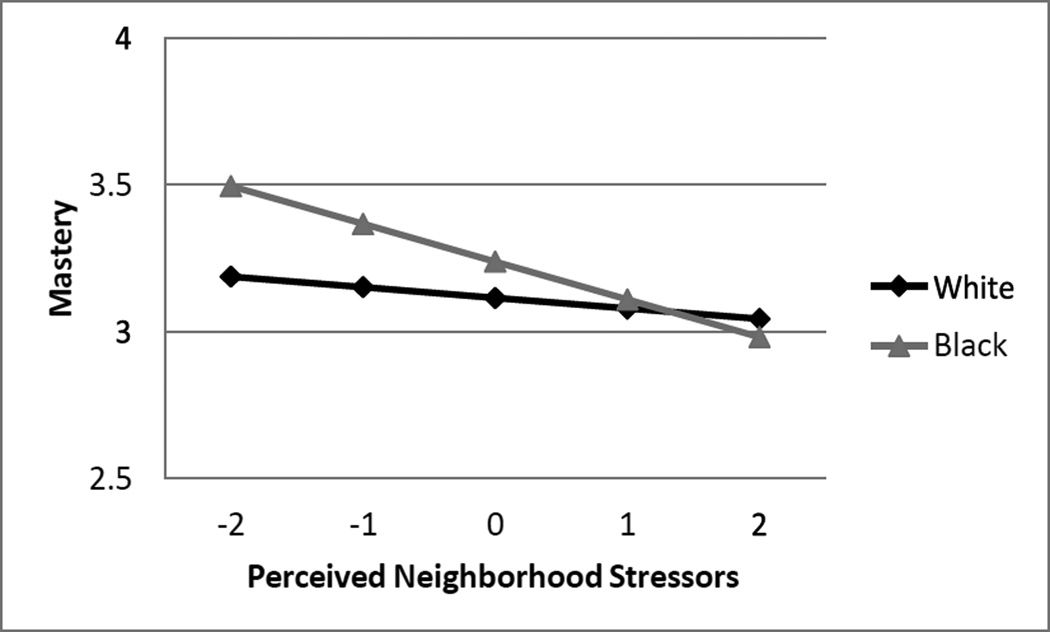

Model 4 examines racial and ethnic differences in the effects of perceived neighborhood stressors. The interaction between Black race and perceived neighborhood stressors is statistically significant in the direction expected. One standard deviation higher score in perceived neighborhood stressors is associated with a .036 lower mastery score for non-Hispanic Whites and a .130 lower score for Blacks. The difference in coefficients is small. Nevertheless, the race difference in neighborhood effect means that in highly stressful neighborhoods, Blacks have lower mastery scores than non-Hispanic Whites. Figure 1 displays the predicted mastery scores for Blacks and Whites as a function of neighborhood stressors. Here you can see that at higher levels of neighborhood stressors, the racial disparity changes direction. In low stress neighborhoods, Blacks have higher mastery. In very high stress neighborhoods, Blacks have lower mastery. The negative relationship between neighborhood stressors and mastery for Hispanics was not significantly different from non-Hispanic Whites, offering no support for the hypothesis for Hispanic respondents.

Figure 1.

Predicted values of mastery by race interacted with perceived neighborhood stressors (Model 4 of Table 2; all other variables at zero).

DISCUSSION

This research sought to examine a compound disadvantage model of the neighborhood stress process among a sample of Black and Hispanic residents of Chicago. By employing measures of neighborhood stressors that were not biased by same source reporting, this research improves our understanding of the neighborhood context of mastery. These results contribute to our understanding of the stress process model, particularly as it pertains to ecological stressors. Results indicate support for the compound disadvantage model for Blacks, but not for Hispanics. Furthermore, findings suggest that the neighborhood context contributes to differences in mastery scores between Whites and Blacks.

The results of the present research suggest that disordered neighborhoods have ill effects on residents, in addition to the ill effects of other social and economic disadvantage (i.e., less education and low income) that may have brought them to live in such neighborhoods. This disadvantage is not simply additive. Disordered neighborhoods have a greater magnitude of ill effects for Black residents than for White residents. Previous research has not investigated the compound disadvantage model of neighborhood effects on mastery. One study found the opposite (i.e., compound advantage) when investigating neighborhood stressors as an individual- level construct (Kim & Conley, 2011), but these results may be specific to the effect of individually reported neighborhood stressors rather than more objectively measured ones, or to the racially segregated context of Chicago.

This study also contributes to the literature by demonstrating that racial group differences in levels of mastery may be contingent on the neighborhood context. Blacks have a higher appraisal of personal mastery when residing in low-stress neighborhoods. However, neighborhood stressors lower their mastery scores more. The relationship between neighborhood stressors and mastery for Whites is also negative, but much smaller and not significant. In high stress neighborhoods, average mastery scores are lower for Blacks than Whites. As suggested earlier, Blacks’ limited mobility out of disadvantaged neighborhoods may translate into neighborhood conditions having a stronger negative effect on their mastery.

While finding support compound disadvantage of neighborhood stressors for Blacks, this study did not find support for compound disadvantage among Hispanic residents of Chicago. It showed no significant differences in mastery or the effect of neighborhood stressors on mastery between Whites and Hispanic respondents in the final models. This study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that inconsistent findings of racial and ethnic disparities in levels of mastery may relate to the neighborhood in which respondents live; disparities exist in high stress neighborhoods but not low stress neighborhoods.

The strengths and weaknesses of the present study should be considered when evaluating these findings. While the data are well suited to studying neighborhood contexts and race and ethnicity, they come from Chicago only. Further, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow for causal inference. The process of social stratification in residential neighborhoods may contribute to selection bias, further hampering causal inference. In particular, those with more mastery may select out of disadvantaged neighborhoods. While these limitations affect generalizability and causal inferences, the data’s strength lies in the sample’s racial and ethnic diversity. Further, the study’s use of neighborhood-level measures of both perceived and observed neighborhood stressors improves upon prior research.

The findings from this study support Aneshensel’s call for further investigation of group-specific effects in the stress process. The neighborhood stress process model has potential for helping us better understand inequality and mental health. Group differences in the magnitude of neighborhood stressors’ effects on coping may, in turn, be associated with group differences in mental health status. Further theory development and testing of the impact of neighborhood stressors on Hispanic and Latino residents is necessary to understand similarities to Whites found in this study. Future research should further investigate the pathways of the stress process and group differences in diverse samples such as the one used in this study.

This study demonstrated that neighborhood stressors are an important component of racial and ethnic differences in mastery. Understanding group differences in psychological resources is important for improving mental health services. Future research should investigate racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between neighborhood stressors and other psychological resources. Certainly, other coping resources may have more impact on the mental health of different racial and ethnic groups, but neighborhood conditions may also influence this difference. Finally, as researchers more frequently use diverse samples, improving our understanding of health and mental health disparities requires further analysis of racial and ethnic differences in exposures and responses to stressors.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear modeling of individual and neighborhood factors on mastery (n=3105)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | Coef | Coef | Coef | |||||

| Individual level | ||||||||

| Race and Ethnicity (non-Hispanic white reference) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | −0.096 | ** | 0.040 | 0.073 | + | 0.043 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.034 | 0.079 | * | 0.137 | *** | 0.123 | ** | |

| Other non-Hispanic | −0.163 | * | −0.193 | ** | −0.184 | ** | −0.109 | |

| First Generation Immigrant | −0.062 | + | −0.060 | −0.057 | ||||

| Female | −0.048 | + | −0.047 | + | −0.047 | + | ||

| Employment status (employed reference) | ||||||||

| Unemployed | −0.081 | + | −0.077 | + | −0.078 | + | ||

| Retired | −0.290 | *** | −0.288 | *** | −0.289 | *** | ||

| Home caregiver | −0.021 | −0.018 | −0.019 | |||||

| Student | 0.173 | * | 0.170 | * | 0.167 | * | ||

| Education (less than 12 years reference) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 0.174 | *** | 0.157 | *** | 0.158 | *** | ||

| 13–15 years | 0.255 | *** | 0.235 | *** | 0.232 | *** | ||

| 16+ years | 0.392 | *** | 0.369 | *** | 0.363 | *** | ||

| Marital Status (Married reference) | ||||||||

| Separated | −0.026 | −0.013 | −0.011 | |||||

| Divorced | 0.029 | 0.040 | 0.035 | |||||

| Widowed | −0.023 | −0.020 | −0.024 | |||||

| Never married | 0.029 | 0.037 | 0.038 | |||||

| Income (40K + reference) | ||||||||

| <5K | −0.266 | *** | −0.255 | *** | −0.252 | *** | ||

| 5–15K | −0.270 | *** | −0.255 | *** | −0.255 | *** | ||

| 15–40K | −0.094 | ** | −0.084 | * | −0.087 | * | ||

| Missing | −0.179 | *** | −0.176 | *** | −0.175 | *** | ||

| Age (18–29 excluded) | ||||||||

| 30–39 | −0.018 | −0.019 | −0.017 | |||||

| 40–49 | −0.076 | + | −0.078 | + | −0.073 | + | ||

| 50–59 | −0.073 | −0.077 | −0.078 | |||||

| 60–69 | −0.130 | * | −0.145 | * | −0.144 | * | ||

| 70+ | −0.088 | −0.104 | −0.106 | |||||

| Residential Stability (5+ years) | 0.050 | + | 0.049 | + | 0.054 | + | ||

| Neighborhood level | ||||||||

| Perceived neighborhood stressors | −0.081 | ** | −0.036 | |||||

| Observed neighborhood stressors | 0.002 | |||||||

| Cross-level interactions | ||||||||

| Hispanic * Perceived neighborhood stressors | −0.054 | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black * Perceived neighborhood stressors | −0.094 | * | ||||||

| Other non-Hispanic * Perceived neighborhood stressors | 0.153 | |||||||

| Intercept | 3.227 | *** | 3.153 | *** | 3.117 | *** | 3.144 | *** |

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Acknowledgments

The Chicago Community Adult Health study was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50HD38986 and R01HD050467). This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32HD049302). The author would like to thank members of the Chicago Community Adult Health research group for comments on earlier versions of this research.

References

- Aneshensel CS. Neighborhood as a Social Context of the Stress Process. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Shieman S, Wheaton B, editors. Advances in the Conceptualization of the Stress Process: Essays in Honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MA, Thornton MC. It's my world? exploring Black and white perceptions of personal control. Sociological Quarterly. 2004;45(3):597–612. [Google Scholar]

- Christie-Mizell CA, Erickson RJ. Mothers and mastery: The consequences of perceived neighborhood disorder. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70(4):340–365. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría S, Diez-Roux A, Shea S, Borrell LN, Jackson S. Associations of Neighborhood Problems and Neighborhood Social Cohesion with Mental Health and Health Behaviors: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health & Place. 2008;14:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis KJ, Ross CE. A new look at urban alienation: The effect of neighborhood disorder on perceived powerlessness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;61(3):232–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster ME. Putting Activism in Its Place: The Neighborhood Context of Participation In Neighborhood-Focused Activism. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2014a;36:33–50. doi: 10.1111/juaf.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilster ME. Neighborhood Stressors, Mastery, and Depressive Symptoms: Racial and Ethnic Differences in an Ecological Model of the Stress Process in Chicago. Journal of Urban Health. 2014b doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9877-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Maimon D. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. Springer; 2013. Neighborhood context and mental health; pp. 479–501. [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Borenstein-Graves A, Haley WE, Small BJ, Mortimer JA. Determinants of a sense of mastery in African American and white older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58(4):S221–S224. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith VM, Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Discriminatory experiences and depressive symptoms among African American women: Do skin tone and mastery matter? Sex Roles. 2010;62(1–2):48–59. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt KJ, Hughes M, Keith VM. Can a high sense of control and John Henryism be bad for mental health? Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50(4):693–714. [Google Scholar]

- King KE, Morenoff JD, House JS. Neighborhood context and social disparities in cumulative biological risk factors. Psychosomatic medicine. 2011;73(7):572. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318227b062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:101–117. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Conley ME. Neighborhood disorder and sense of personal control: Which factors moderate the association? Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;39:894–907. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Segregation and stratification: A biosocial perspective. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2004;1(01):7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mizell CA. Life course influences on African American men's depression: Adolescent parental composition, self-concept, and adult earnings. Journal of Black Studies. 1999;29(4):467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ. Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Social Forces. 1997;76(1):31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, House JS, Hansen BB, Williams DR, Kaplan GA, Hunte HE. Understanding social disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control: the role of neighborhood context. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;65(9):1853–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: From psychometrics to ecometrics. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165(8):858–867. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Morton A, Lieberman, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19(1):2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 6 for windows [computer software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: Toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociological Methodology. 1999;29:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of "broken windows". Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(4):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pearlin LI, Meersman SC. Neighborhood disadvantage and anger among older adults: Social comparisons as effect modifiers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(2):156–172. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Deane GD. Race and residential mobility: Individual determinants and structural constraints. Social Forces. 1993;72:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata: Release 13. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Clarke P. Space meets time: Integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:680–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, Ko MJ, Aneshensel CS. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms in late middle age. Research on Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0164027510383048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.