Abstract

The inhibitor of neuraminidase (NA), oseltamivir, is a widely used anti-influenza drug. However, oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 influenza viruses carrying the H275Y NA mutation spontaneously emerged as a result of natural genetic drift and drug treatment. Because this and other potential mutations may generate a future pandemic influenza strain that is oseltamivir-resistant, alternative therapy options are needed. Here show that a structure-based computational method can be used to identify existing drugs that inhibit resistant viruses, thereby providing a first line of pharmaceutical defense against this very possible scenario. We identified two drugs, nalidixic acid and dorzolamide, that potently inhibit the NA activity of oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 viruses with the H275Y NA mutation at very low concentrations, but have no effect on wild-type H1N1 NA even at a much higher concentration, suggesting that the oseltamivir-resistance mutation itself caused susceptibility to these drugs.

Keywords: drug discovery, influenza viruses, neuraminidase, computational chemistry, drug repurposing

During the early stages of any influenza pandemic, specific vaccines are unavailable; therefore, effective drugs are the only means of preventing the spread of infection.[1] The 2009 H1N1 pandemic, for example, reached its peak well before a vaccine became available in the United States.[2] The potent neuraminidases (NA) inhibitor oseltamivir (Tamiflu) is the most widely used anti-influenza drug. However, oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 influenza viruses carrying the H275Y NA mutation spontaneously emerged worldwide as a result of natural genetic drift and drug treatment.[3] NA catalyzes the hydrolysis of sialic acid residues between newly formed virions and host glycoproteins to allow virion release. Oseltamivir was designed to fit perfectly into the NA enzyme active site of influenza virus. This site is altered in oseltamivir-resistant viruses, inhibiting binding of the drug. Most oseltamivir-resistant strains of seasonal and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus to date have carried the H275Y NA mutation.[4] This mutant has a bulky hydrophobic side chain at Y275 that forces the E277 side chain to rotate, disrupting the intramolecular E277-R225 electrostatic interactions normally formed upon binding to oseltamivir. The E277 side chain is also forced toward the center of the NA sialic acid binding site by the side chain of Y275. These changes reduce the binding affinity of the site for the large aliphatic side chain of oseltamivir.[5] Had oseltamivir-resistant viruses dominated during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic mortality would have been much greater.

We reasoned that available drugs that are structurally similar to oseltamivir may bind to the mutant NA active site and that sensitivity to these drugs may be enhanced by the structural changes in the mutant NA binding site. To search for such drugs, we used hierarchical computational screening.[6] We first conducted combined 2D/3D shape screening[7] of the library of current FDA-approved drugs.[8] Using a 0 (no overlap) to 1 (identical shape) scale, we selected approximately 300 compounds whose structural shapes have similarity > 0.7 to that of oseltamivir. We then docked each of these compounds to the active site of the H275Y-mutant N1 NA, using the conformation of oseltamivir bound to the wild-type N1 NA at this site[5a, 5c] as the reference. The docking results were visually inspected to ensure that the key (“hotspot”[9]) interactions between the bound drugs and H257Y-mutant N1 NA in the docked complexes had a maximum overlap with the key interactions between the bound oseltamivir and wild-type N1 NA. The 20 compounds with the highest docking scores were selected, and their structures in complex with H275Y N1 NA were refined by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies[10] using 5-ns unrestrained simulation with explicit solvation and calculation of molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) binding free energy.[11] The 10 compounds with the highest calculated binding free energy were selected for further testing.

The 10 compounds were tested against two oseltamivir-sensitive (A/Brisbane/59/2007 and A/Netherlands/049/2008) and two oseltamivir-resistant (A/New Jersey/15/2007 and A/Netherlands/028/2008) H1N1 influenza viruses. The NA sequences of all four strains were confirmed in our laboratory and showed >85% similarity to those of the 1918 pandemic H1N1, 2009 pandemic H1N1, and highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses. The NA activity of the viruses and the inhibitory constants of the selected compounds were measured by using an established fluorescence–based NA enzyme inhibition assay.[12]

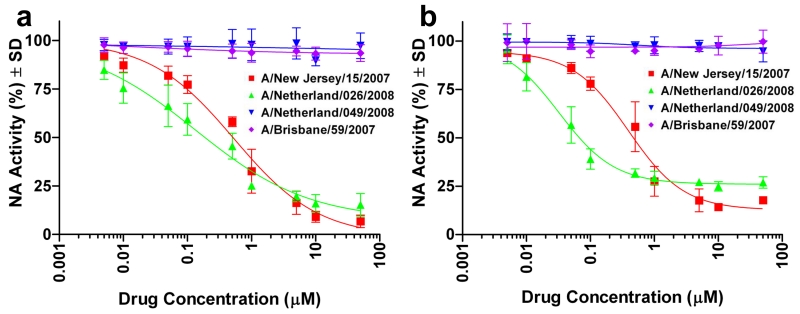

Although several drugs inhibited the NA activity of the resistant and nonresistant viruses to some extent (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information), nalidixic acid and dorzolamide exerted a selective inhibitory effect against the two oseltamivir-resistant strains. In additional confirmatory testing (four independent measurements at each concentration), both compounds stably inhibited the NA activity of both oseltamivir-resistant strains in a dose-dependent manner and at a sub-micromolar 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) but did not inhibit the NA activity of the oseltamivir-susceptible strains (Figure 1). Of the two compounds, nalidixic acid is of particular interest, as it was the first synthetic quinolone antibiotic and is widely used in treating bacterial infections,[13] while dorzolamide is most used in eye drop for glaucoma treatment.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent inhibition of NA activity in oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 influenza strains. a, Nalidixic acid: IC50 = 0.68 ± 0.11 μM for A/New Jersey/15/2007 and 0.21 ± 0.06 μM for A/Netherlands/026/2008. b, Dorzolamide: IC50 0.49 ± 0.08 μM for A/New Jersey/15/2007 and 0.030 ± 0.004 μM for A/Netherlands/026/2008. The two drugs show no effect on two oseltamivir-susceptible (wild-type) H1N1 viruses (A/Brisbane/59/2007 and A/Netherlands/049/2008). IC50 values were derived from the mean NA activity at each drug concentration in four independent tests.

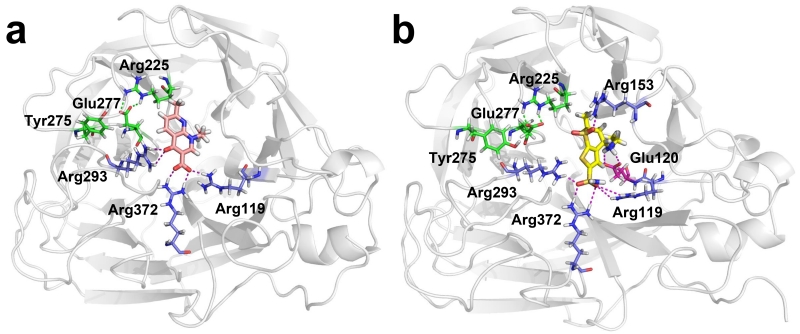

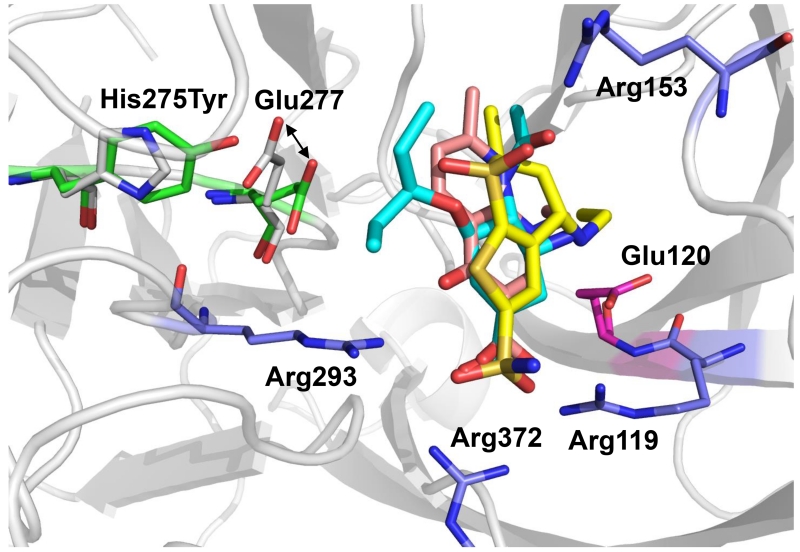

We used MD simulation studies to examine the binding of the two compounds to the H275Y NA mutant in detail. In both complexes, a salt bridge (observed in neither starting structure) formed between E277 and R225 of NA after approximately 500 ps; this salt bridge was previously observed in wild-type NA (but not H275Y mutant NA) bound to oseltamivir[5b ] (Figure 2). The bound conformations of nalidixic acid and dorzolamide closely resembled that of oseltamivir with the exception of the oseltamivir hydrophobic side chain, which sterically hindered its binding to H275Y N1 NA (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Modeled conformations of the two drugs in complex with NA. a. His275Tyr N1 NA in complex with nalidixic acid (carbon atoms are in light magenta). b. His275Tyr N1 NA in complex with dorzolamide (carbon atoms are in yellow). Polar contacts between compounds and His275Tyr mutant N1 NA are shown as purple dashed lines. Salt bridge contacts between the NA Arg225 and Glu277 residues (green dashed lines) are disrupted in interactions with oseltamivir but restored in interactions with nalidixic acid and dorzolamide. The Tyr275 residue is shown in all systems for reference. Carbon atoms of residues with basic side chains are shown in blue; carbon atoms of residues with acidic side chains are shown in dark magenta.

Figure 3.

Comparison of modeled conformations of drugs in complex with wild-type and H275Y-mutant N1 NA. The structures of the wild-type and mutant are superimposed. Carbon atoms of His275 and Glu 277 of wild-type are in gray; carbon atoms of Tyr 275 and Glu 277 are in green. In the complexes, carbon atoms of oseltamivir carboxylate are shown in cyan; carbon atoms of nalidixic acid are shown light magenta; carbon atoms of dorzolamide are shown in yellow.

Oseltamivir interacts with N1 NA at several key hotspots; it forms salt bridges with three arginines (R119, R293 and R372) and E120 and forms a hydrogen bond with R153 (Figure 3). The acidic group of nalidixic acid and the sulfonamide group of dorzolamide bind to the H275Y N1 NA in a manner similar to that of the oseltamivir acidic group, interacting with three arginine residues (R119, R293 and R372) (Figure 2). In addition, the secondary amine group of dorzolamide forms salt bridges with D152 and E120 (which interact with the primary amine group of oseltamivir), and the dorzolamide sulfone group forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of R153, as does the amide group of oseltamivir (Figure 2b). Although some of the interactions observed between oseltamivir and wild-type NA are lacking in the binding of nalidixic acid and dorzolamide to the H275Y N1 NA mutant active site, restoration of the E277-R225 salt bridge appears to generate a similar binding affinity.

To further investigate why the two drugs do not bind to wild-type N1 NA, we used MD simulations and MM-PBSA binding calculations. Nalidixic acid remained stably within the sialic acid binding site of wild-type NA, but its calculated binding free energy, which was 5 kcal/mol less than that of binding to H275Y N1 NA, demonstrated ineffective binding. This finding may be explained by the absence of specific electrostatic interactions, which are important in determining the binding orientation of wild-type N1 NA despite their small contribution to binding energetics.[14] In the case of dorzolamide, its hydrophilic nature caused wide fluctuation of its position in wild-type N1 NA binding sites during MD simulations, indicating the absence of binding to wild-type N1 NA.

Influenza-specific NA inhibitors are a unique class of drugs[15] designed to mimic sialic acid, the influenza NA substrate. Our 2D/3D shape screening results suggest that the chemical space and the spatial shape of this sialic acid mimetic overlaps with those of the other two drugs. Our structural studies suggest that off-targets of current NA inhibitors and other scaffolds for potent NA inhibitors are rarely reported because wild-type N1 NA is markedly sensitive to substrate shape and specific functional groups. Indeed, the fact that nalidixic acid and dorzolamide inhibit only oseltamivir-resistant N1 NA demonstrates that the slight alteration of the substrate recognition profile of N1 NA caused by the H275Y mutation enhances its vulnerability to some compounds that do not bind efficiently to wild-type N1 NA. On the other hand, because the N1 NA active site is highly conserved in both the wild-type and oseltamivir-resistant strains, the structure of an oseltamivir-resistant mutant NA can be modeled on the basis of the wild-type structure and the model can then be used in structure-based ligand screening to identify small-molecule drugs (e.g., dorzolamide and nalidixic acid) that target the mutant strain.

This proof of principle study demonstrates that drug resistance caused by a specific influenza N1 NA mutation (H275Y in this case) can be circumvented by using drug repositioning and structure-based computational methods to identify alternative agents. Although it is difficult to predict the site(s) of future NA mutations that may cause oseltamivir resistanc,[16] the conformational changes induced by these mutations can be predicted after the NA is sequenced.[5b] Therefore, our protocol can be used to circumvent future NA mutations that cause oseltamivir resistance and may be useful in rapidly controlling the spread of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic influenza viruses.[17] This approach also allows the identification of existing drugs that bind and inhibit various viruses (or microorganisms) that have acquired drug-resistance mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by by NIH grants GM100909 and CA21765 (Cancer Center Support Grant), by NIH Contract HHSN266200700005C, and by Research to Prevent Blindness. We thank Richard J. Webby for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript and Sharon H. Naron for editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dr. Ju Bao,

Dr. Bindumadhav Marathe,

Dr. Elena A. Govorkova,

Professor Jie J. Zheng, .

References

- [1].a Fedson DS. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2009;3:129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Salomon R, Webster RG. Cell. 2009;136:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sambhara S, Poland GA. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:187–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.050908.132031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Collin N, de Radigues X. Vaccine. 2009;27:5184–5186. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a Meijer A, Lackenby A, Hungnes O, Lina B, van-der-Werf S, Schweiger B, Opp M, Paget J, van-de-Kassteele J, Hay A, Zambon M. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:552–560. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.081280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hurt AC, Ernest J, Deng YM, Iannello P, Besselaar TG, Birch C, Buchy P, Chittaganpitch M, Chiu SC, Dwyer D, Guigon A, Harrower B, Kei IP, Kok T, Lin C, McPhie K, Mohd A, Olveda R, Panayotou T, Rawlinson W, Scott L, Smith D, D’Souza H, Komadina N, Shaw R, Kelso A, Barr IG. Antiviral Res. 2009;83:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Takashita E, Meijer A, Lackenby A, Gubareva L, Rebelo-de-Andrade H, Besselaar T, Fry A, Gregory V, Leang SK, Huang W, Lo J, Pereyaslov D, Siqueira MM, Wang D, Mak GC, Zhang W, Daniels RS, Hurt AC, Tashiro M. Antiviral Res. 2015;117:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a Brockwell-Staats C, Webster RG, Webby RJ. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2009;3:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Deyde VM, Sheu TG, Trujillo AA, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten R, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1102–1110. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01417-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Stoner TD, Krauss S, DuBois RM, Negovetich NJ, Stallknecht DE, Senne DA, Gramer MR, Swafford S, DeLiberto T, Govorkova EA, Webster RG. J Virol. 2010;84:9800–9809. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00296-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a Collins PJ, Haire LF, Lin YP, Liu J, Russell RJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Martin SR, Hay AJ, Gamblin SJ. Nature. 2008;453:1258–1261. doi: 10.1038/nature06956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang NX, Zheng JJ. Protein Sci. 2009;18:707–715. doi: 10.1002/pro.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li Q, Qi J, Zhang W, Vavricka CJ, Shi Y, Wei J, Feng E, Shen J, Chen J, Liu D, He J, Yan J, Liu H, Jiang H, Teng M, Li X, Gao GF. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1266–1268. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a Watts KS, Dalal P, Murphy RB, Sherman W, Friesner RA, Shelley JC. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:534–546. doi: 10.1021/ci100015j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sastry GM, Dixon SL, Sherman W. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2455–2466. doi: 10.1021/ci2002704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a Dixon SL, Smondyrev AM, Knoll EH, Rao SN, Shaw DE, Friesner RA. J.Comput.Aided Mol.Des. 2006;20:647–671. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dixon SL, Smondyrev AM, Rao SN. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 2006;67:370–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, Shrivastava S, Hassanali M, Stothard P, Chang Z, Woolsey J. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D668–D672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a Clackson T, Wells JA. Science. 1995;267:383–386. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cukuroglu E, Engin HB, Gursoy A, Keskin O. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2014;116:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Case DA, Cheatham TE, III, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr., Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. J.Comput.Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a Srinivasan J, Cheatham TE, Cieplak P, Kollman PA, Case DA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998;120:9401–9409. [Google Scholar]; b Massova I, Kollman PA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121:8133–8143. [Google Scholar]; c Feig M, Onufriev A, Lee MS, Im W, Case DA, Brooks CL., III J.Comput.Chem. 2004;25:265–284. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yen HL, Ilyushina NA, Salomon R, Hoffmann E, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. J Virol. 2007;81:12418–12426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01067-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a Carroll G. J Urol. 1963;90:476–478. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Emmerson AM, Jones AM. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(Suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Masukawa KM, Kollman PA, Kuntz ID. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5628–5637. doi: 10.1021/jm030060q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].von Itzstein M. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nrd2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a Yen HL, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Choy KT, Wong DD, Cheung PP, Zhou J, Ng IH, Zhu H, Webby RJ, Guan Y, Webster RG, Peiris JS. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00396-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Song MS, Marathe BM, Kumar G, Wong SS, Rubrum A, Zanin M, Choi YK, Webster RG, Govorkova EA, Webby RJ. J Virol. 2015;89:10891–10900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01514-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wong DD, Choy KT, Chan RW, Sia SF, Chiu HP, Cheung PP, Chan MC, Peiris JS, Yen HL. J Virol. 2012;86:10558–10570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00985-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.