Abstract

Background

Responsiveness to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rosiglitazone safety alert, issued on May 21, 2007, has not been examined among vulnerable subpopulations of the elderly.

Objective

To compare time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone after the safety alert between black and white elderly persons, and across sociodemographic and economic subgroups.

Research Design

A cohort study.

Subjects

Medicare fee-for-service enrollees in 2007 who were established users of rosiglitazone identified from a 20% national sample of pharmacy claims.

Measures

Outcome of interest was time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone after the May alert. We modeled the number of days following the warning to the end of the days’ supply for the last rosiglitazone claim during the study period (May 21, 2007–December 31, 2007) using multivariable proportional hazards models.

Results

More than 67% of enrollees discontinued rosiglitazone within six months of the advisory. In adjusted analysis, white enrollees (hazard ratio = 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.86–0.94) discontinued rosiglitazone later than the comparison group of black enrollees. Enrollees with a history of low personal income also discontinued later than their comparison group (hazard ratio = 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.81–0.87). There were no observed differences across quintiles of area-level socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

White race and a history of low personal income modestly predicted later discontinuation of rosiglitazone after the FDA’s safety advisory in 2007. The impact of FDA advisories can vary among sociodemographic groups. Policymakers should continue to monitor whether risk management policies reach their intended populations.

Keywords: risk communication, FDA policy, elderly, high-risk drugs, risk mitigation strategies

On May 21, 2007, concurrent with the online publication of a widely anticipated meta-analysis,1 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety alert warning of a “potentially significant increase in the risk of heart attacks in patients taking the oral antidiabetic Avandia (rosiglitazone).”2 Because other treatment options were available, and most people with diabetes are at high risk for cardiovascular disease,3,4 the expectation was that the majority of patients would discontinue use of the drug.5

Use of rosiglitazone nationally decreased from 11% to 3% of total dispensings for oral diabetes medications within two years after the safety alert.6 Little research has evaluated whether the effectiveness of FDA safety communications varies as a function of racial and sociodemographic characteristics, especially among the most vulnerable elderly. The pervasiveness and scope of disparities in health care is well known, and may extend to exposure to high-risk drugs.7–13 Because FDA advisories can have a varied impact on medication use,14 understanding whether these interventions equitably affect patient subgroups can inform future risk mitigation strategies.

Although the FDA recommended lifting restrictions on rosiglitazone in November of 2013,15,16 the agency continues to utilize alerts as a tool to communicate serious concerns about drug safety. We used data from Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) Part D recipients to quantify differences in time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone between black and white enrollees and among different sociodemographic and socioeconomic subgroups.

METHODS

Data Sources

We obtained the 2007 Medicare Part D Prescription Event file for a national random sample of 20% of Medicare FFS enrollees. This file contains pharmacy claims for every outpatient prescription filled for an enrollee in the sample. We linked the Part D file to the Medicare Enrollment file, Prescriber Characteristics file, and Part A Inpatient and Part B Outpatient claims files for the same year. The Enrollment file includes information on sociodemographic characteristics of enrollees, including race,17 zip code of residence, and eligibility for Medicaid and low-income Part B subsidies. Diagnosis codes and health care utilization variables came from the Part A inpatient claims and the Part B outpatient files. The Prescriber Characteristics File contains provider specialty information.18

We constructed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) socioeconomic status (SES) index score for each beneficiary using zip code information linked to the 2000 United States Census data. The SES index score is calculated at the census block level with a greater score associated with better neighborhood SES. Composition and justification of the score is described in detail by AHRQ.19

Study Population

The study population consisted of black and white enrollees, 65 years of age and older, who were current users of rosiglitazone on the date of the May 21, 2007 safety advisory. An enrollee was considered a current user if they had at least two claims for rosiglitazone between January 1, 2007 and May 21, 2007 and if the period defined by the final dispensing date in the preadvisory period (hereafter referred to as the index rosiglitazone claim) plus the days’ supply overlapped with the date of the advisory. We required at least two fills of rosiglitazone to identify enrollees with a persistent pattern of use and a days’ supply ≤ 31 days for the index rosiglitazone claim.

The period before the May advisory was used to ascertain sociodemographic information, baseline clinical history, and health care utilization covariates. We classified enrollees as having a history of cardiovascular disease if they had the following ICD-9 diagnosis codes in the Medicare Part A and Part B files between January 1, 2007 and the date of the FDA alert:

Acute myocardial infarction[AMI (410.x)]

Coronary Atherosclerosis or ischemic heart disease [IHD (410.x–414.x, 429.2, V45.81, V45.82)]

Congestive Heart Failure [CHF (398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.03, 404.13, 425.x, 428.9)]

Peripheral and Visceral Atherosclerosis [ATH (440. 1–440.23)] or

Surgical procedure codes [36.0x through 36.3x for removal of obstruction and insertion of stents, bypass surgery, and revascularization]

Outcome Measure

Our outcome of interest was time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone, defined as the number of days from the end of the days’ supply of the index rosiglitazone claim (the index end date) to the end of the days’ supply for the last rosiglitazone claim during the study period (May 21, 2007–December 31, 2007), the date of death, or end of study period, whichever came first. If the days’ supply of the last prescription claim came after the end of the study period, the patient follow-up time was censored on December 31, 2007.

Race, Low Personal Income, and SES

The primary independent variables of interest were enrollee race, a history of low personal income defined by at least 1 month of enrollment in Medicaid or any state Medicaid low-income subsidy assistance for Medicare Part B premiums and cost-sharing during the baseline period20 (hereafter referred to as low personal income), and SES index score (by quintile). We focused on black and white enrollees because previous research has validated the race variable for black and white enrollees in Medicare data,21 whereas coding for other racial groups, including Hispanics, has been found to be less accurate.

Covariates

Additional covariates of interest were age (categorical), sex, US Census division of residence (9 divisions total), medication possession ratio (MPR) for rosiglitazone in the baseline period before the May warning, and receipt of any oral nonthiazolidinedione diabetes medication in the preperiod (yes/no). The MPR was calculated in the baseline period as the sum of the days’ supply of rosiglitazone over the 140 days of the period. The final MPR covariate was designated as a binary indicator with an MPR ≥ 1 representing enrollees with refill patterns sufficient to meet prescribed doses in the preperiod, and those with an MPR < 1 with comparatively lower adherence. Health utilization parameters of interest were number of outpatient visits to a provider in the baseline period (≤ 2 evaluation and management claims or >2 claims) and prescriber specialty (categorized as endocrinology/cardiology or other).

Observation Period

The observation period for this study began May 21, 2007, when the Nissen and Wolski1 meta-analysis was published online and the FDA safety alert was contemporaneously communicated to the public through the FDA web site as well as to health care providers through “Dear Doctor” letters. Censoring occurred at death or study end date (December 31, 2007).

Statistical Analysis

We employed survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier estimation with log-rank tests of equality of the cumulative hazards functions, as well as Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. We compared crude and adjusted time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone in the full analytic sample and among enrollees with a history of cardiovascular disease. The fully adjusted models included all the covariates described previously. Follow-up time for each patient was defined as the period from the index end date until the earlier of the end of the study or the date of death. The appropriateness of the Cox model assumption of proportional hazards was confirmed and all variables were tested for noncollinearity.

We conducted all analyses using the statistical analysis software Stata, version 13.0, and SAS, version 9.2. The Brown University Institutional Review Board and the CMS Privacy Board approved this study.

RESULTS

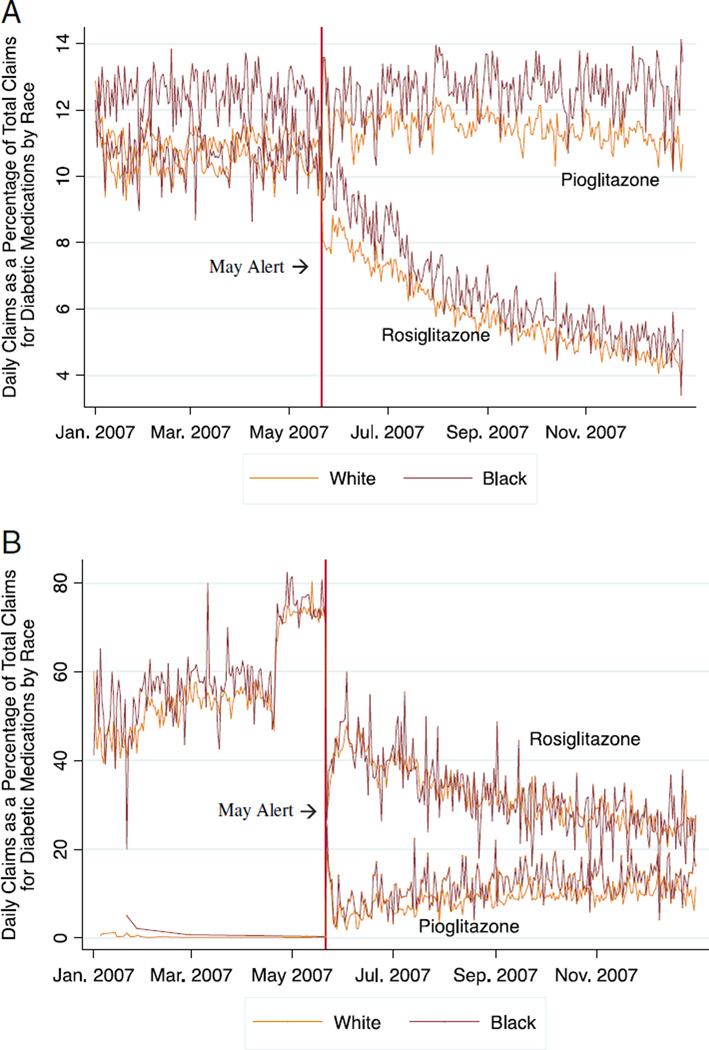

Our analytic sample consisted of 37,412 white users of rosiglitazone among whom 23% had a history of cardiovascular disease and 7862 black users among whom 19% had cardiovascular disease. Figures 1A and B plot the percentage of total oral diabetic claims that were rosiglitazone or pioglitazone (the alternate drug in the thiazolidinedione class) in the entire 2007 Medicare Part D sample and in our study sample, respectively. Following the warning, rosiglitazone use decreased markedly among black and white enrollees in both samples, whereas pioglitazone use increased slightly.

FIGURE 1.

A, Daily percentage of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone claims per total oral diabetic medication claims, among all black and white 2007 Medicare Part D fee-for-service enrollees aged 65 years and above in a 20% national sample (n = 784,159 enrollees)*. B, Daily percentage of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone claims per total oral diabetic medication claims in 2007 in a study sample of black and white Medicare fee-for-service enrollees aged 65 years and above defined as current users of rosiglitazone before the May 21, 2007 FDA safety alert (n = 45,274). *Percentages based on entire sample of Part D prescription claims information for a 20% nationally representative sample of Medicare fee-for-service enrollees available to investigators. Denominator does not include claims for insulin-based pharmaceutical products.

In the full sample and among those with a history of cardiovascular disease, black enrollees were more likely to be female, have a history of low personal income, and live in communities of lower SES (Table 1). The median follow-up time for all current users was 209 days, and was consistent between racial groups. Approximately 4% of white and 3% of black enrollees died during the study period. An additional 29% of white and 29% of black enrollees had calculated discontinuation dates after December 31, 2007 (the study end date).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Geographic Characteristics of Current Users of Rosiglitazone in Medicare Feefor-Service Study Sample at Index Date by Race*

| Characteristics | White Rosiglitazone Users (n=37,412) (%) |

Black Rosiglitazone Users (n=7862) (%) |

White Rosiglitazone Users With History of Cardiovascular Disease (n=8776) (%) |

Black Rosiglitazone Users With History of Cardiovascular Disease (n=1471) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 60.5 | 69.9 | 57.5 | 72.4 |

| Age group (y) | ||||

| 65–69 | 30.9 | 34.6 | 25.0 | 30.9 |

| 70–74 | 26.2 | 27.8 | 24.6 | 27.5 |

| 75–79 | 20.5 | 19.0 | 22.4 | 19.1 |

| 80–84 | 13.4 | 10.8 | 16.8 | 12.6 |

| ≥ 85 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 11.2 | 9.9 |

| Low personal income | 34.8 | 60.7 | 45.5 | 72.2 |

| SES index score by zip code [mean (SD)] | 49.68 (4.0) | 48.14 (3.8) | 49.77 (3.8) | 47.95 (3.5) |

| US Census division | ||||

| New England | 5.4 | 2.3 | 5.7 | 1.7 |

| Middle Atlantic | 14.9 | 18.6 | 15.6 | 16.0 |

| East North Central | 14.9 | 11.6 | 16.0 | 14.6 |

| West North Central | 8.7 | 2.4 | 9.5 | 2.4 |

| South Atlantic | 19.5 | 34.8 | 17.8 | 34.1 |

| East South Central | 8.8 | 13.9 | 9.1 | 12.6 |

| West South Central | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 13.4 |

| Mountain | 6.2 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.6 |

| Pacific | 10.7 | 4.1 | 10.3 | 4.5 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 23.5 | 18.7 | — | — |

| Medication adherence | ||||

| High adherence MPR ≥ 1 | 43.8 | 38.0 | 41.5 | 36.4 |

| Low adherence MPR < 1 | 56.2 | 61.9 | 58.5 | 63.6 |

| No. outpatient visits | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 59.5 | 64.7 | 30.0 | 33.7† |

| > 2 | 40.5 | 35.3 | 69.9 | 67.2 |

| Provider type | ||||

| Endocrinology/cardiology | 5.0 | 3.9 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

| Other | 94.9 | 96.1 | 93.6 | 93.8 |

| Receipt of ≥ 1 non-TZD oral DM claim in preperiod | 33.3 | 39.1 | 63.8 | 54.9 |

The SES index score is derived from zip code-level US Census variables based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s specifications; higher SES values imply higher SES (US mean, 50). All numbers refer to percentages, with the exception of SES index score.

To compare baseline characteristics in both study samples among black and white enrollees, P-values were computed for dichotomous variables using the χ2 test and for continuous variables using the t test; except where italicized, all tests resulted in P-values < 0.000 or where designated with an

the P-value was less than < 0.05.

DM indicates diabetes mellitus; MPR, medication possession ratio; non-TZD, a medication not in the thiazolidinedione class; SES, socioeconomic status; y, years.

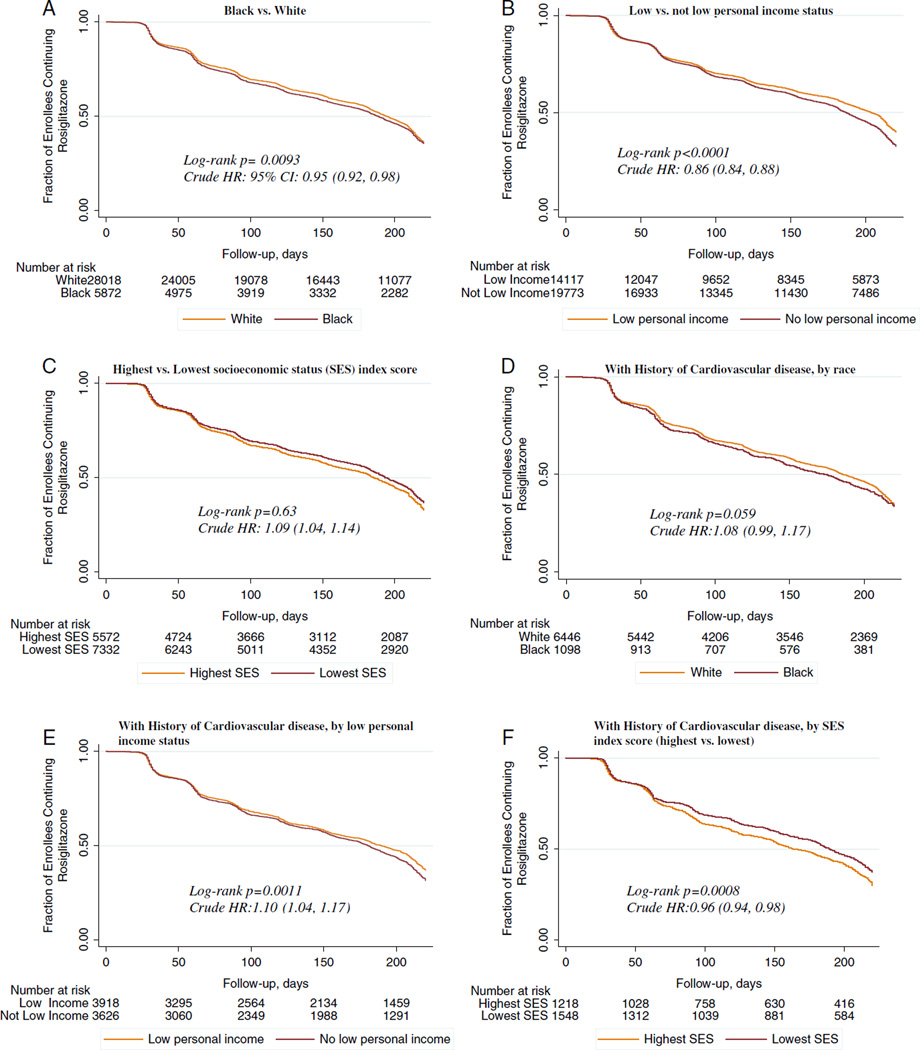

The median time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone among all current users was 107 days. Among all white enrollees, median time to discontinuation was 110 days, 12 days later than the median time for black enrollees (Fig. 2A). Among the study population not censored, 30,491 enrollees or 67% of the entire sample discontinued rosiglitazone by the end of the study period (ie, within the six-month period after the safety advisory); 67% of white enrollees (n = 25,105) and 69% of black enrollees (n = 5386).

FIGURE 2.

A–F, Kaplan-Meier curves of discontinuation of rosiglitazone in black and white Medicare fee-for-service enrollees aged 65 years and above defined as current users of rosiglitazone before the May 21, 2007 FDA safety alert (n = 45,274) and among a subsample of these enrollees with a history of cardiovascular disease (n= 10,247). A, Black versus white. B, Low versus not low personal income status. C, Highest versus lowest SES index score. D, With history of cardiovascular disease, by race. E, With history of cardiovascular disease, by low personal income status. F, With history of cardiovascular disease, by SES index score (highest vs. lowest). Low personal income is defined as at least one month of Medicaid enrollment or low income subsidy from January 1 to May 21, 2007; the SES index score is derived from zip code-level US Census variables based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s specifications; they represent community-level indices of SES. CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SES, socioeconomic status.

In unadjusted analysis, enrollees with a history of low personal income discontinued a median of 31 days later than those with no history of low personal income. Those in the lowest SES quintile discontinued a median 30 days later than those in the highest SES category (Figs. 2B, C).

Among enrollees with a history of cardiovascular disease, white enrollees had a median time to discontinuation of 92 days, compared with 91 days for black enrollees (Fig. 2D). Differences among those with low personal income and SES groups remained comparable to the full sample results (Figs. 2E, F).

In the fully adjusted Cox proportional hazards analysis (Table 2), white enrollees [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.88–0.95], enrollees with a history of low personal income (HR = 0.84, 95% CI, 0.81–0.86), male enrollees (HR = 0.96, 95% CI, 0.93–0.99), those with no history of cardiovascular disease (HR = 0.90, 95% CI, 0.87–0.94), and those without concomitant nonthiazolidinedione oral diabetic medication in the preperiod (HR = 0.89, 95% CI, 0.86–0.92) discontinued rosiglitazone later than their respective comparator groups. There were no marked differences across quintiles of SES, provider type, and census division groups. Among enrollees with a history of cardiovascular disease (Table 3), we found that the strongest factors related to earlier discontinuation were similar to those in the full sample. To further explore the relationship of race, personal income, and cost to our outcome of interest, we also ran the full model with a covariate for copay level and additional models stratified by race and copay. The results of these analyses are included in the Appendix (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B115).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis of Variable Association With Time to Discontinuation of Rosiglitazone After May 21, 2007 Safety Advisory in Black and White Medicare Fee-for-Service Enrollees (n = 45,274)

| Variables | Total (N) | Cases *(N) | Follow-up Time (Person-Years) |

Crude Difference in Median Time to Discontinuation (d) |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||

| Black (reference) | 7862 | 5386 | 4387 | — | — |

| White | 37,412 | 25,105 | 20,787 | 12 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.95) |

| Personal income | |||||

| Not low (reference) | 27,451 | 19,403 | 15,374 | — | — |

| Low | 17,823 | 11,088 | 9799 | 31 | 0.84 (0.81, 0.86) |

| SES index score quintile | |||||

| Quintile 5, lowest (reference) | 9560 | 6348 | 5340 | — | — |

| Quintile 1, highest | 7784 | 5506 | 4337 | −30 | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) |

| Quintile 2 | 8281 | 5589 | 4578 | −15 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.03) |

| Quintile 3 | 10,390 | 6939 | 5773 | −7 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.03) |

| Quintile 4 | 9259 | 6109 | 5146 | −1 | 0.97 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (reference) | 28,149 | 18,970 | 15,676 | — | — |

| Male | 17,125 | 11,521 | 9497 | 8 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) |

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 65–69 (reference) | 14,300 | 9989 | 8096 | — | — |

| 70–74 | 12,009 | 8228 | 6763 | 6.5 | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) |

| 75–79 | 9161 | 6185 | 5094 | 0.5 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98) |

| 80–84 | 5866 | 3789 | 3185 | 15.5 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.97) |

| ≥ 85 | 3938 | 2300 | 2035 | 34.5 | 0.83 (0.78, 0.88) |

| US Census division | |||||

| New England (reference) | 2144 | 1472 | 1186 | — | — |

| Middle Atlantic | 6854 | 4932 | 3826 | −19.5 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.18) |

| East North Central | 6312 | 4151 | 3498 | 28.5 | 0.93 (0.87, 1.01) |

| West North Central | 3346 | 2014 | 1859 | 67.5 | 0.79 (0.73, 0.86) |

| South Atlantic | 9758 | 6740 | 5438 | 2.5 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) |

| East South Central | 4266 | 2695 | 2377 | 34.5 | 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) |

| West South Central | 4815 | 3210 | 2665 | 14.5 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) |

| Mountain | 2338 | 1559 | 1295 | 32.5 | 0.95 (0.87, 1.04) |

| Pacific | 4200 | 2859 | 2328 | 4.5 | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) |

| Cardiovascular (CV) disease | |||||

| History of CV disease (reference) | 10,247 | 7044 | 5633 | — | — |

| No history of CV disease | 35,027 | 23,447 | 19,540 | 24 | 0.90 (0.87, 0.94) |

| Medication adherence | |||||

| Low adherence (reference) (MPR <1) | 25,903 | 18,141 | 14,575 | — | — |

| High adherence (MPR ≥ 1) | 19,371 | 12,350 | 10,599 | 38 | 0.88 (0.85, 0.91) |

| Health service utilization | |||||

| ≤ 2 Outpatient visits (reference) | 27,359 | 18,084 | 15,180 | — | — |

| > 2 Outpatient visits | 17,915 | 12,407 | 9993 | −26 | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) |

| Receipt of non-TZD DM medication‡ | |||||

| Yes (reference) | 29,730 | 20,504 | 16,597 | — | — |

| No | 15,544 | 9987 | 8576 | 26 | 0.89 (0.86, 0.92) |

| Provider type | |||||

| Endocrinology/ Cardiology (reference) | 2198 | 1588 | 1228 | — | — |

| Other | 43,076 | 28,903 | 23,945 | 25.5 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) |

Cases defined as enrollees not censored who discontinue rosiglitazone before the end of study period.

We fit Cox-proportional hazard models to adjust for the selected covariates; confidence intervals that do not cross 1 are significant at P < 0.05; hazard ratio (HR) < 1 implies later discontinuation than comparator group and HR > 1 implies earlier discontinuation than comparator group.

Receipt of at least 1 claim for a nonthiazolidinedione oral diabetic medication in the baseline period before the May 21, 2007 advisory.

CI indicates confidence interval; d, days; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; MPR, medication possession ratio; non-TZD, a medication not in the thiazolidinedione class; SES, socioeconomic status; y, years.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis of Variable Association with Time to Discontinuation of Rosiglitazone After May 21, 2007 Safety Advisory in Black and White Medicare Fee-for-Service Enrollees With a History of Cardiovascular Disease (n = 10,247)

| Variables | Total (N) | Cases* (N) | Follow-up Time (Person-Years) |

Crude Difference in Median Time to Discontinuation (d) |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||||

| Black (reference) | 1471 | 1032 | 813 | — | — |

| White | 8776 | 6012 | 4820 | 1 | 0.88 (0.81, 0.97) |

| Personal income | |||||

| Not low (reference) | 5188 | 3752 | 2884 | — | — |

| Low | 5059 | 3292 | 2748 | 23 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) |

| SES index score quintile | |||||

| Quintile 5, lowest (reference) | 2033 | 1347 | 973 | — | — |

| Quintile 1, highest | 1750 | 1284 | 948 | −32 | 1.13 (1.01, 1.26) |

| Quintile 2 | 1733 | 1175 | 1359 | −16 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) |

| Quintile 3 | 2475 | 1697 | 1235 | −18 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.16) |

| Quintile 4 | 2256 | 1541 | 1118 | −14 | 1.07 (0.97, 1.17) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (reference) | 6108 | 4192 | 3365 | — | — |

| Male | 4139 | 2852 | 2268 | 1 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) |

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 65–69 (reference) | 2653 | 1898 | 1492 | — | — |

| 70–74 | 2560 | 1785 | 1432 | 5 | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) |

| 75–79 | 2245 | 1555 | 1236 | 5 | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) |

| 80–84 | 1656 | 1101 | 890 | 8 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.03) |

| ≥ 85 | 1133 | 705 | 582 | 25 | 0.90 (0.81, 1.00) |

| US Census division | |||||

| New England (reference) | 526 | 387 | 291 | — | — |

| Middle Atlantic | 1597 | 1148 | 884 | 10 | 0.97 (0.83, 1.13) |

| East North Central | 1619 | 1095 | 884 | 32 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.98) |

| West North Central | 867 | 559 | 477 | 74 | 0.82 (0.69, 0.97) |

| South Atlantic | 2060 | 1449 | 1142 | 24.5 | 0.92 (0.79, 1.08) |

| East South Central | 983 | 654 | 544 | 39 | 0.84 (0.71, 1.00) |

| West South Central | 1212 | 806 | 654 | 31 | 0.84 (0.72, 1.00) |

| Mountain | 386 | 255 | 210 | 58 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) |

| Pacific | 964 | 665 | 528 | 22.5 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) |

| Medication adherence | |||||

| Low adherence (reference) (MPR < 1) | 6069 | 4281 | 344 | — | — |

| High adherence (MPR ≥ 1) | 4178 | 2763 | 2276 | 7 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) |

| Health service utilization | |||||

| ≤ 2 outpatient visits (reference) | 3118 | 1975 | 1665 | — | — |

| > 2 outpatient visits | 7129 | 5069 | 3968 | −33 | 1.11 (1.04, 1.19) |

| Receipt of non-TZD DM medication‡ | |||||

| Yes (reference) | 6414 | 4524 | 3542 | — | — |

| No | 3833 | 2520 | 2091 | 20 | 0.88 (0.83, 0.94) |

| Provider type | |||||

| Endocrinology/ Cardiology (reference) | 653 | 488 | 361 | — | — |

| Other | 9594 | 6556 | 5272 | 29 | 0.93 (0.82, 1.06) |

Cases defined as enrollees not censored who discontinue rosiglitazone before the end of study period.

We fit Cox-proportional hazard models to adjust for the selected covariates; confidence intervals that do not cross 1 are significant at P < 0.05; hazard ratio (HR) < 1 implies later discontinuation than comparator group and HR > 1 implies earlier discontinuation than comparator group.

Receipt of at least 1 claim for a nonthiazolidinedione oral diabetic medication in the baseline period before the May 21, 2007 advisory.

CI indicates confidence interval; d, days; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; MPR, medication possession ratio; non-TZD, a medication not in the thiazolidinedione class; SES, socioeconomic status; y, years.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the majority of current Medicare FFS users of rosiglitazone, including those with a history of cardiovascular disease, discontinued use of the medication within six months after the May safety advisory. Patterns of use in 2007 (Figs. 1A, B) suggest that the precipitous decline in rosiglitazone use after the warning was not offset by an equal increase in use of pioglitazone. White enrollees and enrollees with a history of low personal income discontinued later than their counterparts.

In the adjusted analysis, there were no differences across area-level SES levels; yet we found that male sex, older age, no history of cardiovascular disease, and no receipt of other diabetic medications in the preperiod may play a role in explaining later time to discontinuation of rosiglitazone. The magnitude of all of these associations was small. Among those with a history of cardiovascular disease, white race and low personal income predicted later discontinuation.

The results of this study are consistent with analysis conducted in a Veterans Affairs population that also found black race and a history of cardiovascular disease predictive of earlier discontinuation of rosiglitazone after the safety advisory.22 The principal factors motivating these differences are uncertain. Prior research exploring racial variance in adherence to diabetic medications found consistent earlier discontinuation of diabetic pharmacotherapy among black enrollees with equal access to medications as white enrollees, and suggested that education and other factors related to health literacy and larger mistrust of the health care system may help explain these differences.23 Receipt of poorer quality care in general may cause skepticism of provider instructions and premature discontinuation of medications.24,25

The clinical consequences, if any, of black enrollees discontinuing earlier than white enrollees warrants further investigation, especially if the earlier discontinuation is related to self-motivated changes that do not rely on clinician consultation and appropriate modification of diabetic therapy.26 In a study of rosiglitazone discontinuation in the commercially insured nonelderly, 19.4% of patients who discontinued rosiglitazone and 36.1% of those who discontinued pioglitazone did not have evidence of being prescribed an alternative anti-diabetic drug at follow-up six months later.27

Our findings suggest that enrollees with a history of low personal income discontinued later than enrollees with no history of low personal income, including within categories of race. However, when we included copay in the fully adjusted model, there was no variation by low personal income status, suggesting that the differences by income are explained by cost. The consumer behavior referred to as “moral hazard,” whereby enrollees may be reluctant to forgo even unnecessary care because of the negligible costs associated with it, may help explain this phenomenon.28 Previous research has also found that rosiglitazone use was higher in states with Medicaid programs that continued to cover the drug after the warning as compared with states that did not.29 Efforts at targeting risk mitigation strategies to this population, through for example prior authorization programs that financially incentivize safer prescribing, should be encouraged.

Our unadjusted results suggested a pattern of earlier discontinuation among enrollees living in areas of higher SES. When controlling for health care utilization, differences in discontinuation found in the crude analysis were no longer apparent, perhaps because we controlled for the mediating effect of access to health care on the relationship between SES and responsiveness to the FDA advisory.

The key strength of our study is that we investigated the impact of an FDA safety advisory in a nationally representative elderly population, a population with greater polypharmacy and particular vulnerability to adverse drug events related to high-risk drugs and a population of which little is known in terms of responsiveness to FDA risk minimization policy.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Prescription drug claims do not always reflect actual drug consumption by the enrollee. However, prescription claims remain the standard in terms of ascertaining outpatient medication exposure in secondary data sources.30 We also relied on a relatively short baseline period to derive covariate information related to cardiovascular disease and used enrollment in Medicaid or any low income subsidy as a surrogate for low personal income. The latter approach, while specific to our variable of interest,31 may reflect other conditions apart from low personal income.

We also controlled for a number of factors that may be downstream to the racial and healthcare experience of black enrollees. By doing so, our adjusted analyses may have underestimated the racial differences in our outcome. We have included the unadjusted Cox regression results and the crude differences in median time to discontinuation to reflect baseline differences for the reader. Importantly, we did not quantify the potential shift from rosiglitazone use to pioglitazone use and cannot explain the causal mechanisms underlying the racial differences we found.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that the FDA rosiglitazone warning effectively encouraged current users to discontinue rosiglitazone. However, certain segments of the population appeared more responsive, especially black Medicare enrollees, younger enrollees, and enrollees with no history of low personal income. Additional research to understand the causal mechanisms and the clinical implications of differential responsiveness to FDA safety advisories is warranted for the effective and equitable construction of future risk mitigation tools.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Lori Daiello for facilitating access to the Medicare Prescriber Characteristics file and Dr Dima Qato and Dr Robert Smith for their helpful feedback on the research question.

Supported by a training grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1T32HS019657-01), which provided support for D.M.Q.

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Drug Administration Press Release. FDA issues safety alert on Avandia. [Accessed July 1, 2015];2007 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm108917.htm.

- 3.Daniels LB, Grady D, Mosca L, et al. Is diabetes mellitus a heart disease equivalent in women? Results from an international study of postmenopausal women in the Raloxifene Use for the Heart (RUTH) Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:164–170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preis SR, Pencina MJ, Mann DM, et al. Early-adulthood cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles among individuals with and without diabetes in the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1590–1596. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psaty BM, Furberg CD. Rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2522–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah ND, Montori VM, Krumholz HM, et al. Responding to an FDA warning—geographic variation in the use of rosiglitazone. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2081–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Refaie WB, Gay G, Virnig BA, et al. Variations in gastric cancer care: a trend beyond racial disparities. Cancer. 2010;116:465–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, et al. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qato DM, Trivedi AN. Receipt of high risk medications among elderly enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:546–553. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, et al. Racial segregation and disparities in breast cancer care and mortality. Cancer. 2008;113:2166–2172. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richard P, Alexandre PK, Lara A, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of diabetes care in a nationally representative sample. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai S, Feng Z, Fennell ML, et al. Despite small improvement, black nursing home residents remain less likely than whites to receive flu vaccine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1939–1946. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusetzina SB, Higashi AS, Dorsey ER, et al. Impact of FDA drug risk communications on health care utilization and health behaviors: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012;50:466–478. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitka M. FDA eases restrictions on the glucose-lowering drug rosiglitazone. JAMA. 2013;310:2604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy M. US regulators relax restrictions on rosiglitazone. BMJ. 2013;347:f7144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ, Zaborski LB. The validity of race and ethnicity in enrollment data for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(pt 2):1300–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chronic Condition Data Warehouse. Your source for national CMS Medicare and Medicaid research data. [Accessed May 5, 2012];2012 Available at: http://www.ccwdata.org/data-dictionaries/index.htm.

- 19.Creation of new race-ethnicity codes and socioeconomic status (SES) indicators for Medicare beneficiaries. [Accessed January 27, 2016];2008 Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/medicareindicators/medicareindicators1.html.

- 20.Koroukian SM, Dahman B, Copeland G, et al. The utility of the state buy-in variable in the Medicare denominator file to identify dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries: a validation study. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:265–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldo DP. Accuracy and bias of race/ethnicity codes in the Medicare enrollment database. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;26:61–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi L, Zhao Y, Szymanski K, et al. Impact of thiazolidinedione safety warnings on medication use patterns and glycemic control among veterans with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2011;25:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewey J, Shrank WH, Bowry AD, et al. Gender and racial disparities in adherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2013;165:665–678. 678.e661. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305:675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orrico KB, Lin JK, Wei A, et al. Clinical consequences of disseminating the rosiglitazone FDA safety warning. Am J Manag Car. 2010;16:e111–e116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurren KM, Taylor TN, Jaber LA. Antidiabetic prescribing trends and predictors of thiazolidinedione discontinuation following the 2007 rosiglitazone safety alert. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arrow KJ. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical-care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53:941–973. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross JS, Jackevicius C, Krumholz HM, et al. State Medicaid programs did not make use of prior authorization to promote safer prescribing after rosiglitazone warning. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:188–198. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox E, Martin BC, Van Staa T, et al. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: approaches to mitigate bias and confounding in the design of nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources. Value Health. 2009;12:1053–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Options for determining which CMS Medicare beneficiaries are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid benefits—a technical guidance paper. [Accessed July 1, 2015];2012 Available at: https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/technical-guidance-documentation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.