To the editor

Residual kidney function in dialysis patients is strongly associated with improved outcomes(1) but is difficult to assess.(2) The average of urinary urea and creatinine clearance (CLurea,cr) from carefully performed timed urine collections between dialysis sessions can reliably estimate GFR measured by urinary inulin clearance (the gold standard),(3) but timed urine collections are cumbersome and error prone. Alternative GFR measurement methods include determining plasma clearance of exogenous filtration markers such as iohexol, an 821-Dalton iodinated contrast agent. Plasma and urinary iohexol clearance (CLiohexol) is highly correlated with urinary inulin clearance and sampling for plasma clearance calculations can be minimized to 2 time points.(4) These characteristics make determining plasma CLiohexol attractive for GFR measurement. The goal of our study was to assess the accuracy of plasma CLiohexol versus CLurea,cr in dialysis patients.

Between November 2011 and October 2014, we recruited 40 dialysis patients, 18 years or older, with self-reported ability to produce 1 cup of urine. We simultaneously measured plasma and urinary CLiohexol along with urinary CLurea,cr during a 24-hour inpatient study visit; research nurses closely monitored urine collection. We included a late (24 hour) time point in our calculation of plasma CLiohexol by a 2-compartment model (plasma sampling times: 10, 30 min; 2, 4, 24 h). In 10 participants, we repeated these measurements at a follow-up visit, resulting in 50 (40 baseline + 10 repeats) clearance measurements. We considered CLurea,cr the reference test and plasma and urinary CLiohexol as the index tests, and assessed correlation and median bias between these measures (detailed methods in Item S1).

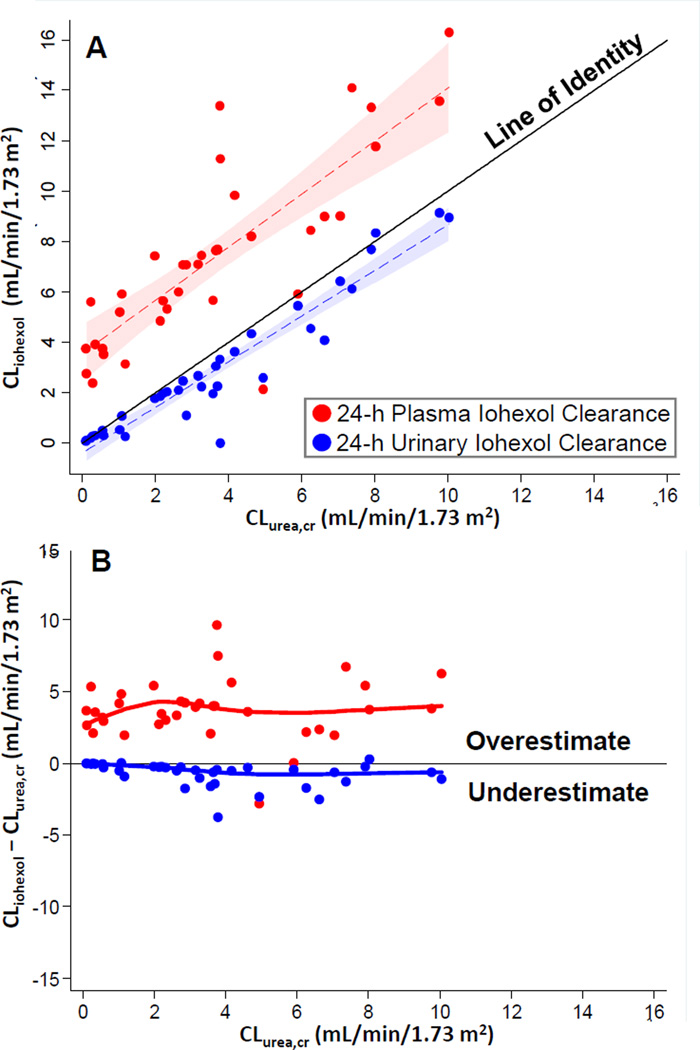

Mean patient age was 55 years, 65% were male, 78% were African American, and 90% were on hemodialysis (Table 1). All clearance measurements are reported in mL/min/1.73 m2, and median [IQR] values were as follows: plasma CLiohexol, 7.1 [5.3–9.4] at 24 hours, 12.7 [7.8–18.0] at 4 hours; 24-hour urinary CLiohexol, 2.3 [0.5–4.3]; and 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr, 3.2 [1.6–5.4]. Plasma CLiohexol at 24 hours was significantly lower than at 4 hours (bias, −4.6 [−5.9 to −3.2]; p < 0.001; Item S1) but significantly higher than 24-hour urinary CLiohexol (bias, 4.4 [3.6–5.2]; p < 0.001) and 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr (bias, 3.7 [3.3– 4.1]; p < 0.001; Figure 1). Also, 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr was higher than 24-hour urinary CLiohexol (bias, 0.5 [0.3–0.7]; p < 0.001) but the overestimation was smaller compared with 24-hour plasma CLiohexol. During follow-up, the correlation and median change in repeat clearance measures was highest for urinary clearances (Item S1). Clearance calculations using a one-compartment model (4- and 24-hour iohexol samples) yielded results similar to the primary analysis (Item S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants and Clearance Measurements in the Residual Kidney Function Study

| Characteristics | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, y | 56 [49–64] |

| Male | 26 (65%) |

| African American | 31 (78%) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Cause of ESRD | |

| Diabetes | 11 (29%) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 5 (14%) |

| Other | 24 (60%) |

| Diabetes | 21 (53%) |

| Hemodialysis | 36 (90%) |

| Peritoneal Dialysis | 4 (10%) |

| Dialysis vintage, mo | 17 [9–36] |

| Height, cm | 173 [164–181] |

| Weight, kg | 88.3 [74.7–115.2] |

| Body Mass Index, Kg/m2 | 30.5 [26.1–35.1] |

| Body Surface Area, m2 | 2.0 [1.9–2.3] |

| 24-Hour Urine Volume, ml | 783 [370–1154] |

| Measured Clearances, ml/min/1.73 m2 | |

| Urinary CLcr | 4.2 [1.9–6.8] |

| Urinary CLurea | 2.6 [0.9–3.9] |

| Urinary CLurea,cr | 3.2 [1.6–5.4] |

| Urinary CLiohexol* | 2.3 [0.5–4.3] |

| Weekly standard renal Kt/Vurea** | 0.6 [0.2–1.1] |

| 4-h plasma CLiohexol*** | 12.7 [7.8–18.0] |

| 24-h plasma CLiohexol | 7.1 [5.3–9.4] |

| Endogenous GFR Markers (Time-Averaged) | |

| Serum Urea Nitrogen, mg/dL | 43 [36–53] |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 6.9 [5.3–10.2] |

Note: N = 40. Values given as median [IQR] or number (percentage). Conversion factors for units: creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, ×88.4; Serum urea nitrogen in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.357

Excludes 3 patients where time from start of urine collection to iohexol injection exceeded 90th percentile (71 min; median was 6 [3–35] min).

Weekly urea clearance by residual kidney function divided by anthropometrically calculated volume of distribution of urea.

Excludes 1 patient in whom this could not be calculated (the extrapolated iohexol concentrations at 10 and 30 min were higher than measured concentrations).

Figure 1. Comparison of Clearance Measurements in the Residual Kidney Function Study.

A Scatterplot of 24-hour plasma (red dots) or urinary (blue dots) CLiohexol vs 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr. The dashed lines and shaded areas represent the linear fit and confidence interval of the regression, respectively, of either 24-hour plasma (red) or urinary (blue) CLiohexol on 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr.

B Plot of 24-hour CLiohexol (plasma, red; urinary, blue) less 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr vs 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr. Positive numbers represent overestimation of 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr; negative numbers, underestimation. The dots represent the difference between the clearance measures and their relation to 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr. The red and blue lines represent fit from a median quantile regression of the bias on 24-hour urinary CLurea,cr.

In our study, plasma CLiohexol was significantly lower at 24 versus 4 hours, a finding consistent with prior observations.(5) At 24 hours, plasma CLiohexol was significantly higher than urinary CLiohexol and urinary CLurea,cr. Possible explanations include hepatic clearance of iohexol, lack of steady-state plasma iohexol concentrations after bolus injection, tubular reabsorption of iohexol, or systematic error in urinary CLurea,cr. In previous animal studies and smaller human studies, nonrenal CLiohexol was noted to be ~2–4 mL/min/1.73 m2,(6,7) with high variability reported in one study.(8) Proximal tubular reabsorption of filtered iohexol has been described in animal models and may explain higher plasma versus urinary CLiohexol.(9) Measurement differences between plasma and urinary CLiohexol could also be due to a matrix effect (using an iohexol assay calibrated in plasma for urine samples).(10)

Study limitations include possible errors in urine collection (lack of bladder catheterization and assessment of urinary retention by bladder ultrasound); absence of measured urinary inulin clearance as a gold-standard reference test, hepatic iohexol clearance, and direct measurements of extracellular volume; and lesser standardization of iohexol in urine than plasma. Strengths include sampling of iohexol at 24 hours and carefully supervised urine collection. In published studies, carefully supervised urinary CLurea,cr is highly reliable in estimating GFR measured by urinary inulin clearance.(3)

In summary, our findings suggest that in dialysis patients with residual kidney function, plasma CLiohexol overestimates urinary CLiohexol and urinary CLurea,cr. Consequently, adjusting dialysis dose based on plasma CLiohexol rather than urine collection may result in dialysis underdosing. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms and variability in renal handling and extrarenal elimination of iohexol and optimal methods to standardize its measurement. A carefully designed study with simultaneous plasma and urinary measurements of iohexol, inulin, and other markers at various levels of GFR is needed to answer these questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, staff, and physicians of DaVita dialysis clinics and the Nephrology Center of Maryland for their support and participation.

Support: Dr. Shafi is supported by grant K23-DK-083514. Research reported in this publication was supported NIDDK (NIH). This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by grant UL1 TR 001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH. The study sponsors did not have any role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Parts of this work were presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology in Philadelphia, PA, November 12–16, 2014.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: TS, ASL, GJS, JC; data acquisition: TS, CK; data analysis/interpretation: TS, ASL, LAI, GJS, AGA, JHE, JC; statistical analysis: TS; supervision or mentorship: ASL, JC. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. TS takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Item S1: Detailed methods and supplementary tables.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery

Supplementary Table S1 (PDF). Detailed methods and supplementary tables.

References

- 1.Shafi T, Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, et al. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:348–358. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S2–S90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milutinovic J, Cutler RE, Hoover P, Meijsen B, Scribner BH. Measurement of residual glomerular filtration rate in the patient receiving repetitive hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1975;8:185–190. doi: 10.1038/ki.1975.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz GJ, Abraham AG, Furth SL, Warady BA, Munoz A. Optimizing iohexol plasma disappearance curves to measure the glomerular filtration rate in children with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009;77:65–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frennby B, Sterner G, Almen T, Hagstam KE, Hultberg B, Jacobsson L. The use of iohexol clearance to determine GFR in patients with severe chronic renal failure--a comparison between different clearance techniques. Clin Nephrol. 1995;43:35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swan SK, Halstenson CE, Kasiske BL, Collins AJ. Determination of residual renal function with iohexol clearance in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1996;49:232–235. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterner G, Frennby B, Mansson S, Ohlsson A, Prutz KG, Almen T. Assessing residual renal function and efficiency of hemodialysis--an application for urographic contrast media. Nephron. 2000;85:324–333. doi: 10.1159/000045682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaspari F, Perico N, Ruggenenti P, et al. Plasma clearance of nonradioactive iohexol as a measure of glomerular filtration rate. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;6:257–263. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V62257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masereeuw R, Moons MM, Smits P, Russel FG. Glomerular filtration and saturable absorption of iohexol in the rat isolated perfused kidney. British journal of pharmacology. 1996;119:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang N, Yu S, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Matrix effects break the LC behavior rule for analytes in LC-MS/MS analysis of biological samples. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, NJ) 2014 doi: 10.1177/1535370214554545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.