Abstract

Using nickel and photoredox catalysis, the direct functionalization of C(sp3)–H bonds of N-aryl amines by acyl electrophiles is described. The method affords a diverse range of α-amino ketones at room temperature and is amenable to late-stage coupling of complex and biologically relevant groups. C(sp3)–H activation occurs by photoredox-mediated oxidation to generate α-amino radicals which are intercepted by nickel in catalytic C(sp3)–C coupling. The merger of these two modes of catalysis leverages nickel’s unique properties in alkyl cross-coupling while avoiding limitations commonly associated with transition-metal-mediated C(sp3)–H activation, including requirements for chelating directing groups and high reaction temperatures.

Keywords: acylation, C–H activation, cross-coupling, nickel, photochemistry

Transition metal catalyzed functionalization of C–H bonds represents a transformative approach to the construction of C–C and C–heteroatom bonds.[1] Its power originates in the ability to accomplish site-selective derivatization of otherwise inert arenes and alkanes without the need for prefunctionalized starting materials. While the direct functionalization of C(sp2)–H bonds is well-represented in the literature, functionalization of C(sp3)–H bonds remains a paramount challenge.[2] Given the emerging value of nickel catalysis in achieving alkyl cross-coupling, its application in C(sp3)–H activation presents an exciting opportunity to develop new C(sp3)–C bond-forming reactions. Recently, transition metal catalyzed C(sp3)–H functionalization reactions with nickel have been reported.[3] However, these methods require the use of coordinating directing groups and high reaction temperatures (>100 °C) to accomplish the key C(sp3)–H activation step, thus limiting their breadth and impact in the context of complex molecule synthesis.

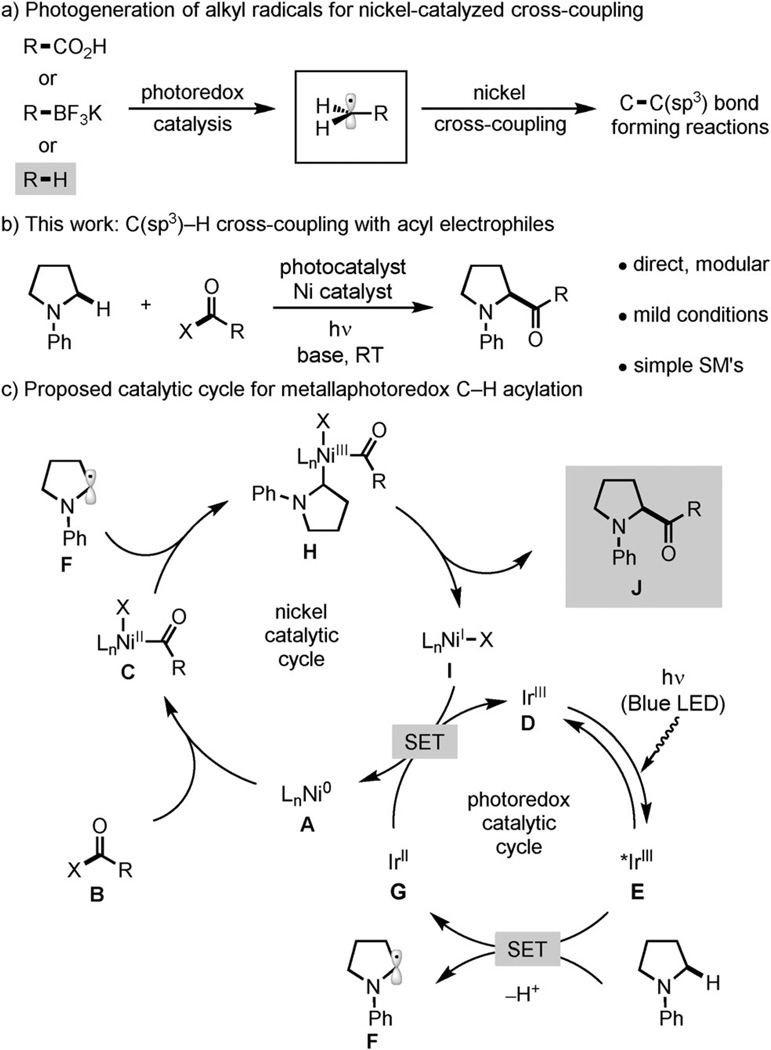

Our group, along with those of MacMillan and Molander, recently reported that the combination of visible-light-mediated photoredox catalysis and nickel catalysis can enable new C(sp3)-type cross-coupling reactions between aryl halides and either alkyl carboxylic acids or alkyl boronates.[4] By using single-electron transfer (SET), the photocatalyst converts the C(sp3) reaction partner into an organic radical, which is intercepted by the nickel catalyst to forge a new C(sp3)–C bond (Figure 1a). Photoredox catalysts can also generate organic radicals from C(sp3)–H bonds by SET.[5] We hypothesized that the combination of photoredox and nickel catalysis could be leveraged to develop novel C(sp3)–H functionalization reactions which take advantage of nickel’s unique characteristics in C(sp3)–C bond formation while avoiding its limitations in the C–H activation step.[6] A proof-of-concept study provided support for this idea, demonstrating that an iridium photocatalyst and nickel catalyst promote arylation of the α-C(sp3)–H bond of N,N-dimethylaniline at room temperature.[4b] Unfortunately, amines bearing β-hydrogen atoms were not competent reaction partners. Given the mildness of these reaction conditions, we sought to demonstrate the value of this approach as a platform for the discovery of novel C(sp3)–H functionalization reactions of broad scope.[7] Herein we report a photoredox and nickelcatalyzed C(sp3)–H coupling of acyl donors with N-aryl amines, including those containing β-hydrogen atoms, a transformation currently not possible using either mode of catalysis alone (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Metallaphotoredox C(sp3)–H cross-coupling with acyl electrophiles. SM=starting material.

This α-amine functionalization reaction[8] generates α-amino ketones in a single step from simple and inexpensive starting materials. Classic approaches to the synthesis of this valuable motif require multistep processes and prefunctionalized reagents.[9, 10] An α-amino C(sp3)–H carbonylation has been previously reported by Murai and co-workers utilizing a rhodium catalyst, CO, and ethylene. However, this reaction requires a 2-pyridyl directing group on the amine substrate, temperatures exceeding 100°C, and only generates ethyl ketones.[11] The metallaphotoredox strategy described herein utilizes instead an N-aryl moiety for the photoredox potential-gated mechanism of C(sp3)–H activation. This key mechanistic feature allows the reaction to take place under exceptionally mild reaction conditions compared to most transition metal catalyzed C(sp3)–H functionalization reactions, thus enabling late-stage coupling of complex and biologically relevant partners.

For the C(sp3)–H acylation reaction, we envisioned a catalytic cycle (Figure 1c) initiated by oxidative insertion of the nickel(0) catalyst A into the acyl-X B to afford the nickel(II)-acyl oxidative adduct C.[12] Concurrently, irradiation of the iridium photocatalyst, [Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)]PF6 (D) (ppy=2-phenylpyridine, dtbbpy=4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-dipyridyl), produces the long-lived excited state complex E (τ = 557 ns).[13] The complex E (E1/2red[*IrIII/IrII] = + 0.70 V vs. SCE in MeCN)[13] can undergo SET with N-phenylpyrrolidine (1; E1/2red = + 0.70 V),[14] which, upon deprotonation, generates the α-amino radical F and reduced iridium(II) species G. Interception of F by C likely affords the nickel(III) complex H. Subsequent reductive elimination forges the C–C bond, thus providing J with concomitant generation of the nickel(I) intermediate I. We expect that both catalytic cycles are closed by SET from the highly reducing G (E1/2red[IrIII/IrII] = −1.5 V vs. SCE in MeCN)[13] to I (E1/2red[NiII/Ni0] = −1.2 V vs. SCE in DMF),[15] thereby reconstituting the nickel(0) catalyst and the iridium(III) photocatalyst.[16]

Our initial investigations began with the coupling of N-phenylpyrrolidine (1) and commercially available propionic anhydride (2a; Table 1). Using [Ni(cod)2], dtbbpy, and [Ir- (ppy)2(dtbbpy)]PF6, it was discovered that the identity of the base was crucial for obtaining high yield of the α-amino ketone product 3.[17] In the absence of exogenous base, 3 was obtained in 65% yield (entry 1). Addition of sodium propionate afforded the desired ketone product in an improved 82% yield (entry 3). However, employing a carboxylate base that was not matched to the anhydride, such as sodium acetate, provided a mixture of methyl and ethyl ketone products, presumably due to the in situ generation of a mixed anhydride. Given the impracticality of using unique carboxylate bases for each anhydride partner, we sought a solution that could be universally applicable. Our attention turned to amine bases. While 3 was obtained in modest yield using DABCO and DBU (entries 4 and 5), switching to quinuclidine provided the coupled product in 83% yield (entry 6).[18] The reaction performs with marginally lower efficiency using NiCl2·glyme, an air-stable nickel precatalyst (entry 7). Notably, control reactions in the absence of a photocatalyst (entry 8), a nickel catalyst (entry 9), and light (entry 10) result in no conversion to product.

Table 1.

Reaction optimization.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry[a] | Reaction conditions | Base | Yield [%][a] |

| 1 | as shown | no base | 65 |

| 2 | as shown | Cs2CO3 | 30 |

| 3 | as shown | NaOC(O)Et | 82 |

| 4 | as shown | DABCO | 37 |

| 5 | as shown | DBU | 57 |

| 6 | as shown | quinuclidine | 83 |

| 7 | NiCl2·glyme as Ni catalyst | quinuclidine | 70 |

| 8 | no photocatalyst | quinuclidine | 0 |

| 9 | no Ni catalyst | quinuclidine | 0 |

| 10 | no light | quinuclidine | 0 |

Yield determined by 1HNMR spectroscopy using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an external standard. DABCO=1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]-octane, DBU=1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene, DMF=N,N-dimethylformamide, dtbbpy=4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-dipyridyl, cod=1,5-cyclooctadiene, ppy=2-phenylpyridine.

With optimized reaction conditions in hand, we investigated the scope with respect to the amine coupling partner (Table 2). A variety of symmetric (4,7) and nonsymmetric (5,6) acyclic N-aryl amines are tolerated, with ketone formation occurring selectively at the less hindered C–H bond. Five-, six-, and seven-membered cyclic amine substrates afford α-amino ketone products in high yields (3, 8–9). Consistent with a sterically driven deprotonation, the generation of the quaternary ketone product is not observed with 2-methyl-N-phenylpyrrolidine. Instead, the tertiary ketone product 11 is formed in 78% yield as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. We were pleased to find that the acylation of pharmacologically important heterocycles, such as indolines (12), tetrahydroquinolines (13), and morpholines (10) occurs smoothly. Furthermore, examination of the substituents on the N-aryl group revealed that a para-methoxyphenyl (PMP) group (14), which can be removed under oxidative conditions to unmask the free amine, is competent under slightly modified reaction conditions. Additionally, electron-withdrawing (15, 16), and ortho-substituents (17) are well tolerated.

Table 2.

Amine scope.[a]

Yield of isolated product is the average of two runs (0.50 mmol).

Contains 10% inseparable diethylaniline.

Used 3.0 equiv of amine.

[Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2] (1 mol%), [Ni(cod)2] (10 mol%), and dtbbpy (15 mol%).

We next investigated the scope with respect to the symmetric anhydride electrophile (Table 3). While acetic anhydride provides the methyl ketone 18 in only moderate yield, the reaction performs well with linear, α-branched (19), and β-branched (20,21) alkyl substituents.[19] Cyclopropyl (22) and cyclohexyl (23) ketones are also synthesized in high yields. The C(sp3)–H acylation is sufficiently mild that a primary alkyl chloride (24) remains unaltered. In addition, an anhydride containing a trisubstituted double bond furnishes the corresponding α,β-unsaturated ketone 25 in good yield.[20]

Table 3.

Symmetric anhydride scope.[a]

Yield of the isolated product is the average of two runs (0.50 mmol).

0.30 mmol scale.

We recognized that in the event that one desires to couple larger or more complex acyl groups, the synthetic utility and atom economy associated with the use of symmetric anhydrides would be diminished. With this consideration in mind, we sought a more general approach using acyl-X reagents, where X serves as a low-molecular-weight and universal leaving group which is amenable to oxidative addition with nickel(0) (Table 4). While only trace product was observed using propionyl chloride (2b), the mixed anhydride 2c (X = 2,6-dimethylbenzoate)[21] afforded the desired ketone product in only slightly attenuated yield compared to that obtained with 2a. Gratifyingly, the 2-pyridylthioester[22] (2d) provided 3 in a yield similar to that obtained with 2a. Thioester substrates offer the benefit over anhydrides of being stable to both aqueous workup and chromatographic purification on silica gel.

Table 4.

Acyl cross-coupling partners.[a]

Yield of the isolated product is the average of two runs (0.50 mmol).

Determined by 1HNMR spectroscopy using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an external standard.

With this strategy in hand, we synthesized an array of thioesters to further showcase the functional-group tolerance of the transformation and its amenability to late-stage functionalization (Table 5). Thioester substrates bearing alkyl, ether, ester, and trifluoromethyl substituents provide the ketone products 3 and 26–28 in good yields. The use of a symmetric anhydride substrate containing a steroidal residue, such as TBS-lithocholic acid, would be highly impractical. Using this modified strategy, the thioester derived from TBS-lithocholic acid delivers the steroidal ketone 29 in 72% yield. To our delight, N-phenylpyrrolidine can also be directly biotinylated to afford 30 in excellent yield without the need for protecting groups, thus highlighting the utility of this dual catalysis platform.

Table 5.

Thioester scope.[a]

Yield of isolated product is the average of two runs (0.50 mmol).

0.30 mmol scale. TBS=tert-butyldimethylsilyl.

In summary, we have developed a novel method for C(sp3)–H acylation mediated by nickel and photoredox catalysis.[23] This protocol enables the direct synthesis of α-amino-ketones from simple N-aryl amines and acyl donors. Importantly, this method can be extended to late-stage coupling of complex and biologically relevant partners. More generally, this work demonstrates that metallaphotoredox catalysis can afford a strategic alternative for C(sp3)–H functionalization and precludes the need for traditional metal-coordinating directing groups on the C–H partner, and features uncommonly mild reaction conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIGMS (R01 GM100985), Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS Center for Molecular Synthesis at Princeton), Eli Lilly, and Amgen is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Eric Simmons (BMS) and Dr. Martin Eastgate (BMS) for helpful discussions. A.G.D. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar and Arthur C. Cope Scholar.

Footnotes

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201511438.

References

- 1.a) Kakiuchi F, Kochi T. Synthesis. 2008:3013–3039. [Google Scholar]; b) Sehnal P, Taylor RJK, Fairlamb IJS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:824–889. doi: 10.1021/cr9003242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamaguchi J, Yamaguchi AD, Itami K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8960–9009. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201666. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 9092–9142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chen DY-K, Youn SW. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:9452–9474. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Jazzar R, Hitce J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:2654–2672. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bellina F, Rossi R. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1082–1146. doi: 10.1021/cr9000836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McMurray L, O’Hara F, Gaunt MJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1885–1898. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15013h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Baudoin O. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4902–4911. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15058h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Li B-J, Shi Z-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:5588–5598. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Rouquet G, Chatani N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11726–11743. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301451. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 11942–11959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Wu X, Zhao Y, Ge H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:1789–1792. doi: 10.1021/ja413131m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Aihara Y, Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:898–901. doi: 10.1021/ja411715v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nakao Y, Morita E, Idei H, Hiyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3264–3267. doi: 10.1021/ja1102037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Tellis JC, Primer DN, Molander GA. Science. 2014;345:433–436. doi: 10.1126/science.1253647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zuo Z, Ahneman DT, Chu L, Terrett JA, Doyle AG, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2014;345:437–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1255525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Noble A, McCarver SJ, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:624–627. doi: 10.1021/ja511913h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chu L, Lipshultz JM, MacMillan DWC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:7929–7933. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501908. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 8040–8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Primer DN, Karakaya I, Tellis JC, Molander GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:2195–2198. doi: 10.1021/ja512946e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Karakaya I, Primer DN, Molander GA. Org. Lett. 2015;17:3294–3297. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Le C, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11938–11941. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Tucker JW, Stephenson CRJ. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:1617–1622. doi: 10.1021/jo202538x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:5322–5363. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yoon TP, Ischay MA, Du J. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nchem.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Xuan J, Xiao W-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:6828–6838. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200223. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 6934–6944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Fagnoni M, Dondi D, Ravelli D, Albini A. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:2725–2756. doi: 10.1021/cr068352x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Xi Y, Yi H, Lei A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:2387–2403. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40137e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasker SZ, Standley EA, Jamison TF. Nature. 2014;509:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalyani D, McMurtrey KB, Neufeldt SR, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18566–18569. doi: 10.1021/ja208068w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Campos KR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1069–1084. doi: 10.1039/b607547a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mitchell EA, Peschiulli A, Lefevre N, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:10092–10142. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Dieter RK. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:4177–4236. [Google Scholar]; b) Singh J, Satyamurthi N, Aidhen IS. J. Prakt. Chem. 2000;342:340–347. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Janey JM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4292–4300. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462314. Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 4364–4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vilaivan T, Bhanthumnavin W. Molecules. 2010;15:917–958. doi: 10.3390/molecules15020917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Ishii Y, Chatani N, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. Organometallics. 1997;16:3615–3622. [Google Scholar]; b) Chatani N, Asaumi T, Ikeda T, Yorimitsu S, Ishii Y, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:12882–12883. doi: 10.1021/ja011540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Fischer R, Walther D, Kempe R, Sieler J, Schönecker B. J. Organomet. Chem. 1993;447:131–136. [Google Scholar]; b) Kajita Y, Kurahashi T, Matsubara S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17226–17227. doi: 10.1021/ja806569h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ochi Y, Kurahashi T, Matsubara S. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1374–1377. doi: 10.1021/ol200044y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhao C, Jia X, Wang X, Gong H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17645–17651. doi: 10.1021/ja510653n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slinker JD, Gorodetsky AA, Lowry MS, Wang J, Parker S, Rohl R, Bernhard S, Malliaras GG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2763–2767. doi: 10.1021/ja0345221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Ma Y, Yin Y, Zhao Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:577–579. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durandetti M, Devaud M, Perichon J. New J. Chem. 1996;20:659–667. [Google Scholar]

- 16.A Ni0/I/III mechanism is also possible: Gutierrez O, Tellis JC, Primer DN, Molander GA, Kozlowski MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4896–4899. doi: 10.1021/ja513079r.

- 17.MacMillan and co-workers recently reported a decarboxylative coupling of anhydrides (Ref. [4g]) by nickel and Ir[dF-(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (E1/2red[*IrIII/IrII] = + 1.21V vs. SCE in MeCN). Our utilization of a less oxidizing photocatalyst may explain why this reaction does not take place

- 18.Stern–Volmer studies show that N-phenyl-pyrrolidine quenches the photoexcited state. No quenching is observed with quinuclidine or propionic anhydride.

- 19.Trimethylacetic anhydride affords trace ketone with 1; using N,N-dimethylaniline provides the tert-butyl ketone in 74%yield.

- 20.Benzoic anhydride provides the aryl ketone in low yield.

- 21.Cherney AH, Kadunce NT, Reisman SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7442–7445. doi: 10.1021/ja402922w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wotal AC, Weix DJ. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1476–1479. doi: 10.1021/ol300217x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.No asymmetric induction is observed with a preliminary evaluation of chiral ligands for nickel.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.