Abstract

Objective:

To establish and evaluate the effectiveness of a comprehensive next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach to simultaneously analyze all genes known to be responsible for the most clinically and genetically heterogeneous neuromuscular diseases (NMDs) involving spinal motoneurons, neuromuscular junctions, nerves, and muscles.

Methods:

All coding exons and at least 20 bp of flanking intronic sequences of 236 genes causing NMDs were enriched by using SeqCap EZ solution-based capture and enrichment method followed by massively parallel sequencing on Illumina HiSeq2000.

Results:

The target gene capture/deep sequencing provides an average coverage of ∼1,000× per nucleotide. Thirty-five unrelated NMD families (38 patients) with clinical and/or muscle pathologic diagnoses but without identified causative genetic defects were analyzed. Deleterious mutations were found in 29 families (83%). Definitive causative mutations were identified in 21 families (60%) and likely diagnoses were established in 8 families (23%). Six families were left without diagnosis due to uncertainty in phenotype/genotype correlation and/or unidentified causative genes. Using this comprehensive panel, we not only identified mutations in expected genes but also expanded phenotype/genotype among different subcategories of NMDs.

Conclusions:

Target gene capture/deep sequencing approach can greatly improve the genetic diagnosis of NMDs. This study demonstrated the power of NGS in confirming and expanding clinical phenotypes/genotypes of the extremely heterogeneous NMDs. Confirmed molecular diagnoses of NMDs can assist in genetic counseling and carrier detection as well as guide therapeutic options for treatable disorders.

Neuromuscular diseases (NMDs) are genetically and clinically heterogeneous. To date, more than 360 genes have been reported to cause NMDs.1 As a group, the combined NMD prevalence is greater than 1 in 3,000.2

The majority of NMDs are inherited, degenerative, and rare.3,4 An early definitive molecular diagnosis is crucial for genetic counseling, family planning, prognosis, therapeutic strategies, and long-term care plans.3–7 The recent development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has accelerated the discovery of novel NMD phenotypes and genotypes,8–11 including the identification of mutations in 5 large NMD genes (TTN, NEB, SYNE1, RYR1, and DMD1,4,8–12) (table e-1 at Neurology.org/ng). With the ever-increasing number of causative genes and clinical heterogeneity, a comprehensive molecular approach with the feasibility to add newly discovered genes for analysis in a cost- and time-effective manner is needed.1,4,7,12–16

A recent study using PCR enrichment and NGS approach to analyze 12 genes known to cause congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) on 26 samples with known mutations17 reported that 49 exons (15%) had insufficient coverage (<20×).17 Among 15 known variants, 6 (40%) were not detected. Similar studies on congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMyS),18 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT),19 Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy,20 and metabolic myopathy (MM)21,22 have demonstrated the clinical utility of NGS in specific disease categories. Nevertheless, these are small-scale studies focusing on subcategories of NMDs. Here, we describe a comprehensive target gene capture/NGS approach, analyzing 236 genes.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was conducted according to the Institutional Review Board–approved protocols of both Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, and Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), Houston, TX. A signed informed consent was obtained for each participant.

Patients and DNA samples.

Patients were clinically evaluated in Taiwan, and DNA samples were analyzed at BCM. DNA samples from 35 unrelated families (38 patients) with clinical diagnoses of NMD who underwent electrophysiologic examination and muscle imaging and/or muscle biopsies were analyzed. Patients with a proven common genetic diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2, CMT type 1A, or facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy were not included in the study. The initial diagnoses included congenital myopathy (CM) (23 patients), CMD (5), limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD)23 (4), CMT (3), MM (2), and myotonic syndrome (MTS) and ion channel muscle disease (1). DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using a Puregene DNA extraction kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Gentra Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

Design of capture probes and target gene enrichment.

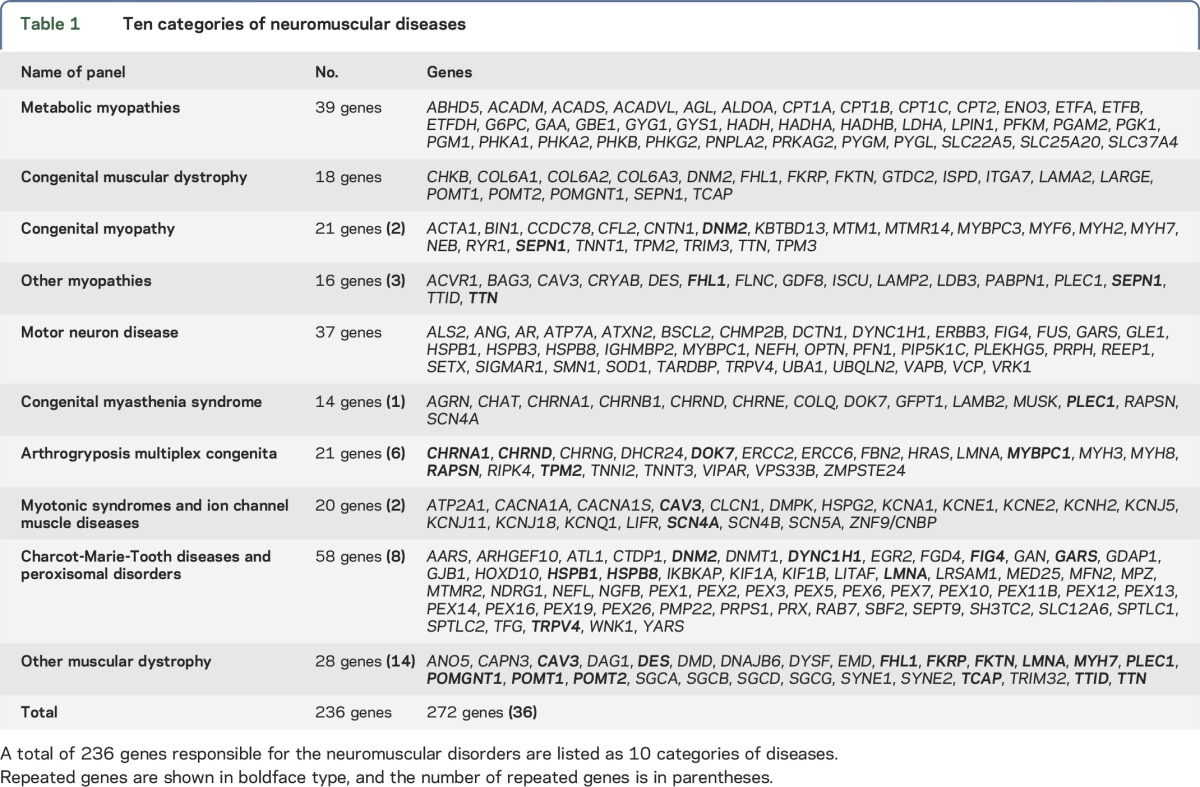

The capture probe library contained 236 genes, most of which were selected from the 2012 version of the gene table of monogenic NMDs.24 We categorized NMDs and their causative genes into 10 groups, including MM, CMD, CM, other myopathies, motor neuron disease, CMyS, arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, MTS and ion channel muscle diseases, CMT, and other muscular dystrophies as listed in table 1. Mitochondrial genes were not included.

Table 1.

Ten categories of neuromuscular diseases

A custom NimbleGen in-solution DNA capture library was designed to capture all 4,815 coding exons and at least 20 bp flanking intron regions of the 236 NMD-related genes. The NM accession numbers of the genes are listed in table e-1. The coding regions were enriched according to manufacturer's instructions (Roche NimbleGen Inc., Madison, WI) and sequencing was performed on HiSeq2000, as previously described.21,25

Sequence alignment and analytical pipeline for variant calling.

Conversion of raw sequencing data, demultiplexing, sequence alignment, data filtering, and analyses using CASAVA v1.7, NextGENe software were performed as previously described.21,25 Multiple in silico analytical tools, such as SpliceSiteFinder-like, MaxEntScan, NNSPLICE, and GeneSplicer, were used to predict the effects of splice site variants (Alamut, http://www.interactive-biosoftware.com). SIFT26 and PolyPhen-227 were used to predict the pathogenicity of novel missense variants. The pathogenicity of the variants was categorized according to published databases, such as Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.biobase-international.com/product/hgmd), PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), and American College of Medical Genetics guidelines.28 The analytical flowchart is depicted in figure e-1. All mutations and novel variants identified by NGS were confirmed independently by Sanger sequencing.21,25 Family members, if available, were also tested to evaluate the mode of inheritance, disease segregation, and clinical correlation.

Detection of deletions using sequence read coverage data from NGS.

We used a newly developed analytical method to detect exonic deletions using the same set of NGS data by comparing the normalized coverage depth of each individual exon of the test sample with the mean coverage depth of the same exon from a group of 20 reference samples.29

RESULTS

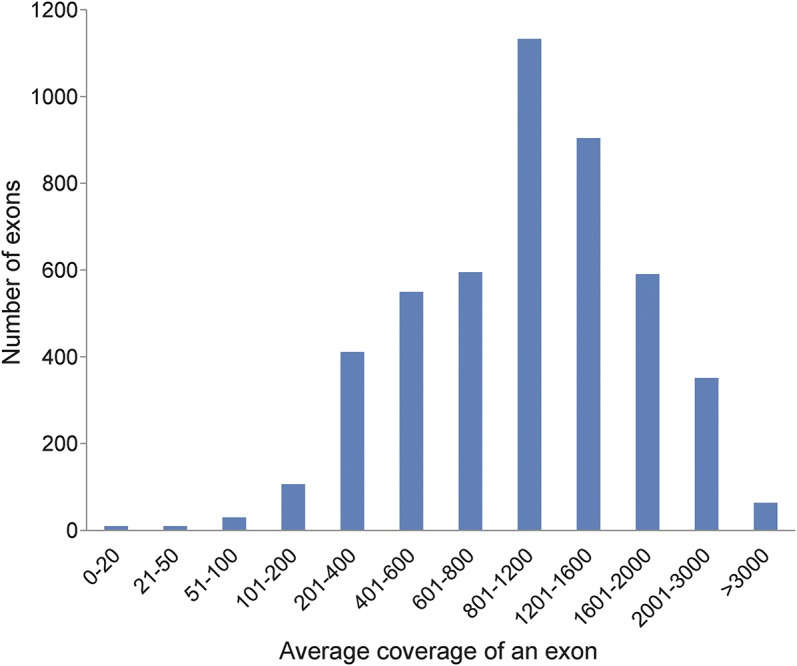

Characteristics of target gene capture and sequence depth.

More than 99.4% (4,787/4,815) of the target sequences were enriched in an unbiased fashion, with a minimal coverage of 20× and a mean coverage depth of 1,136× per base (figure 1). An average of 28 exons per sample was consistently insufficiently sequenced (<20×) due to the high GC content, sequence homologies in the genome, short tandem repeats, or secondary structural difficulties (table e-2).

Figure 1. Coverage depth of 4,815 coding exons of the neuromuscular disease panel.

Clinical history.

A total of 35 unrelated affected families (38 patients) with clinical diagnosis of NMD were studied. Among them, 3 families had 2 affected family members (patients 4/6, 19/20, and 25/26). The male to female patient ratio was about 1 to 1. The majority of patients (27/38, 71%) presented with paralytic floppy infant syndrome (PFIS). The clinical and pathologic features are summarized in table 2.

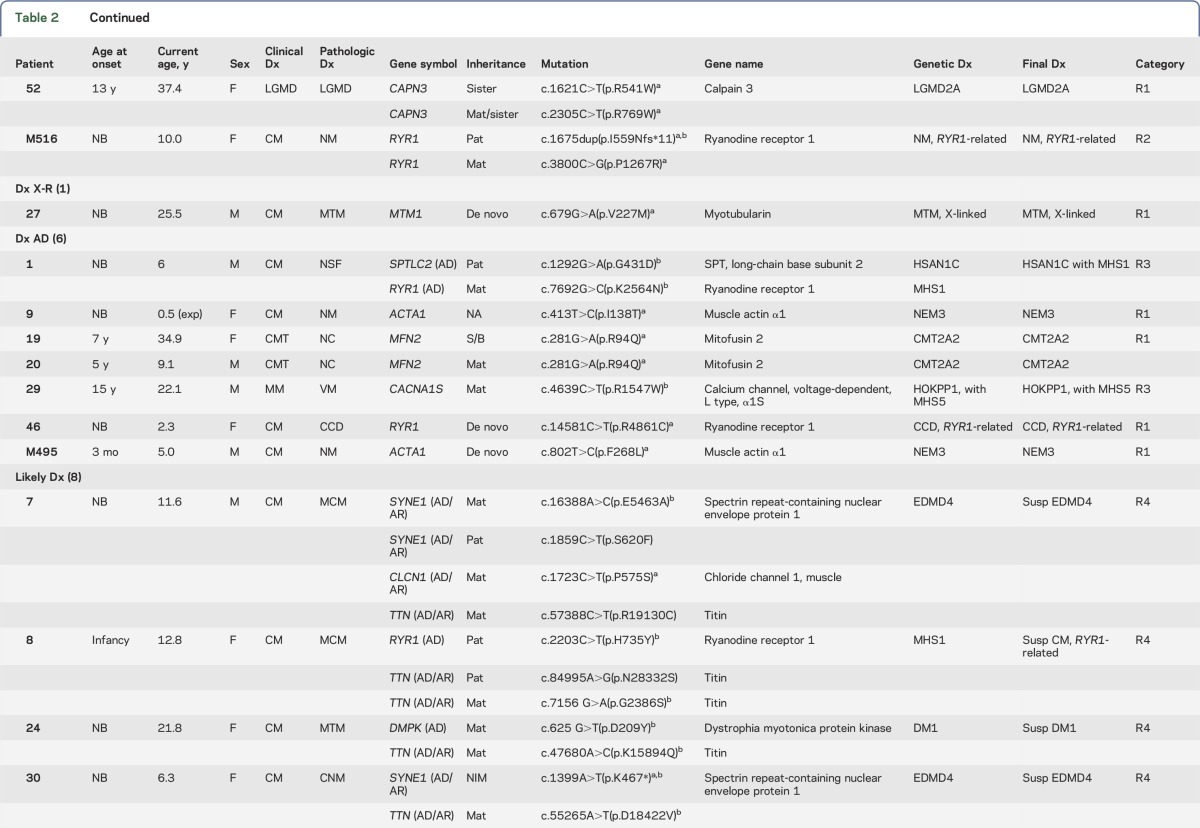

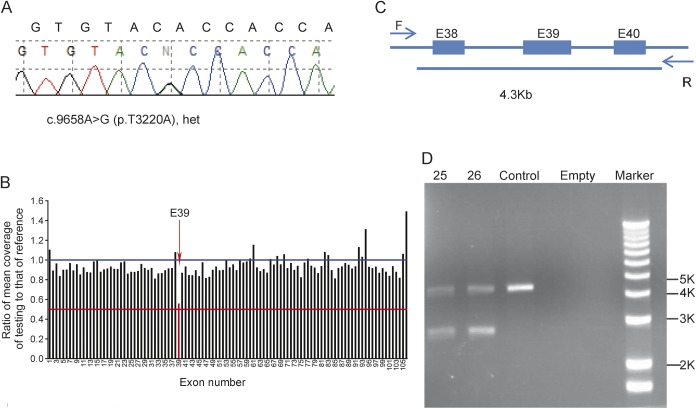

Table 2.

Summary of clinical and molecular diagnosis of patients with neuromuscular diseases

Identification of mutations.

Figure e-1 illustrates the analytical algorithm for the identification of disease-causing variants. The approximate number of variants in each step of analysis is included. DNA sequence variants were considered deleterious if they led to a translational frameshift, exon skipping, or stop codon or if they were previously reported in affected patients. Table 2 summarizes initial clinical diagnoses, muscle pathology findings, mutations identified, and final diagnoses. Among 35 families, 21 families (60%) had definitive diagnoses with deleterious mutations in the expected causative genes that were confirmed in family members. Likely diagnoses were identified in an additional 8 families (23%) that had novel genotype/phenotype findings requiring functional, clinical, and/or genetic confirmation. Six families were without a specific diagnosis due to inconsistent genotype/phenotype correlation based on current knowledge. Similar to the proportion of clinical diagnoses, mutations in genes causing CM were most common. However, this observation is biased due to the prevalence of pediatric patients in our cohort. About half of the disorders are inherited in an autosomal recessive (AR) mode, with 2 X-linked recessive cases. Autosomal dominant (AD) disorders account for about 20%.

Molecular diagnoses of NMDs.

Confirmation of NMD diagnosis: Identification of deleterious mutations in genes responsible for the observed clinical phenotype and muscle pathology.

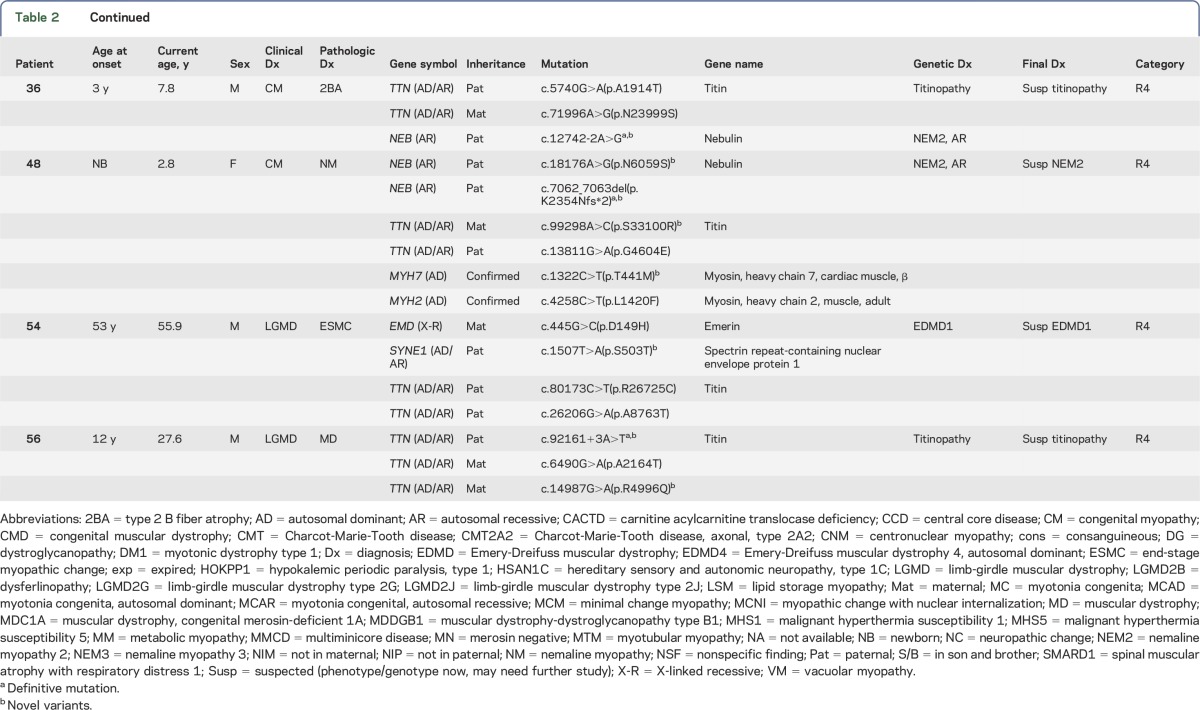

The diagnoses of 13 families have been confirmed by this capture/sequencing approach (R1 in table 2). Patient 2 had presented with MM due to PFIS and hyperammonemia since birth. His muscle pathology was consistent with lipid storage myopathy (figure 2A). He was homozygous for the c.199-10T>G Asian common splice mutation in SLC25A20,22 which is responsible for carnitine acylcarnitine translocase deficiency (CACTD). Each of his parents was a carrier. Patients 3 and 46 with central core disease (CCD) had AR RYR1 mutations and an AD de novo RYR1 mutation, respectively; patients 25 and 26 (siblings) with centronuclear myopathy (CNM) also had AR RYR1 mutations (figure 2B). Patients 11 (figure 2C) and 21 with multiminicore disease had mutations in SEPN1; 2 had nemaline myopathy (NM) and heterozygous ACTA1 mutations (patients 9 [figure 2D] and M495). Patient 16 with merosin-negative CMD had mutations in LAMA2; patients 19 and 20, a mother and son with CMT, had an AD mutation in MFN2; patient 51 with dysferlinopathy and LGMD2B, a consanguineous product, had a homozygous deletion of exon 5 of DYSF; patient 52 and her affected sister with LGMD had the same compound heterozygous mutations in CAPN3; and patient 27 with myotubular myopathy carried a de novo MTM1 mutation (X-linked).

Figure 2. Muscle pathology of patients 2, 26, 11, 9, 32, and 48.

(A) Markedly increased lipid droplets in both number and size were observed in patient 2 with homozygous SLC25A20 mutations (oil red O). (B) Forty percent myofibers with centralized nuclei were found in patient 26 with compound heterozygous RYR1 mutations (hematoxylin and eosin). (C) Multiminicore pattern was observed in patient 11 with compound heterozygous SEPN1 mutations (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase). (D) Prominent nemaline rods were seen in patient 9 with heterozygous ACTA1 mutations (modified Gomori trichrome). (E) Nonspecific myopathic change except for internalized nuclei and mild fiber size variation was shown in patient 32 with compound heterozygous TCAP mutations (hematoxylin and eosin). (F) Similar to patient 9, typical intracytoplasmic nemaline rods were present in patient 48 with compound heterozygous NEB mutations (modified Gomori trichrome).

Ambiguous or nonspecific muscle pathology findings clarified by molecular diagnosis.

Sometimes the pathology findings from a muscle biopsy can be ambiguous and/or not completely consistent with the known phenotype caused by a specific disease gene. Massively parallel sequencing of a group of genes can resolve the uncertainty. Four families belong to this category (R2 in table 2). Patient 12 had reduced α-dystroglycan undiagnosed CMD with end-stage pathologic muscle changes. Compound heterozygous mutations in a protein glycosylation gene (POMT1) were identified and confirmed by parental studies. Patient 17 had nonspecific muscle findings with a clinical diagnosis of a myotonic disorder. He was found to have mutations in a chloride ion channel gene (CLCN1) and confirmed to have an AR myotonia congenita. Patient 33, a 2.7-year-old girl, presented with a myopathic face, high-arched palate, scoliosis, and swallowing and respiratory difficulties since birth. Her muscle pathology revealed nondiagnostic end-stage myopathic changes, although clinically she exhibited typical CM. NGS analysis revealed compound heterozygous mutations in RYR1, which confirmed the diagnosis of CM. Patient M516 had muscle pathology findings suggestive of an atypical NM and was found to have AR RYR1 mutations: one frameshift mutation and another missense mutation predicted to be deleterious. Each parent is a carrier for one of the mutations. This patient adds to the short list of NM cases caused by RYR1 mutations.30

Intercategory expansion of phenotype and genotype.

Four families had molecular diagnoses in genes belonging to a subcategory that was not suspected in the original clinical evaluation (R3 in table 2). Patient 18 was originally diagnosed as having infantile-onset unclassified CMT. The identification of compound heterozygous mutations in IGHMBP2 confirmed the diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1 (SMARD1), mainly affecting motor neurons rather than peripheral nerves. Patient 32, a 32-year-old man, had gait disturbance and mild lower leg weakness with an elevated creatine kinase since he was first evaluated at age 20. Muscle biopsy revealed nuclear internalization without evidence of dystrophic changes in 10% scattered fibers, favoring a diagnosis of CNM (figure 2E). The identification of a homozygous frameshift c.26_33dup (p.Glu12Argfs*20) mutation in TCAP confirmed the diagnosis of LGMD type 2G. Patient 29, a 22-year-old man, was suspected of having an MM due to periodic muscle weakness, abnormal findings in his metabolic profile, and vacuolar myopathy in his muscle biopsy. An AD heterozygous novel mutation inherited from his mother was identified, c.4639C>T (p.Arg1547Trp) in CACNA1S, encoding a calcium channel protein, consistent with hypokalemic periodic paralysis. AD CACNA1S mutations have been found in Asian men with periodic muscle weakness and risk for malignant hyperthermia (MH), but they exhibit lower penetrance in women.31 Patient 1 showed a positive Gowers sign and waddling gait when first evaluated at 4 years of age; however, the EMG, nerve conduction velocity, and muscle pathology were unremarkable at that time. The finding of the AD SPTLC2 mutation c.1292G>A (p.Gly431Asp), confirmed clinically and genetically in his biological father, established the unexpected diagnosis of a neuropathy (hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy [HSAN] type 1C).

Interesting cases with likely diagnosis and expansion of phenotype/genotype.

Eight families had novel phenotype/genotype diagnoses that require further functional evidence of pathogenicity (R4 in table 2). Patient 56 had a clinical and pathologic diagnosis of LGMD. NGS revealed 3 TTN variants: the c.92161+3A>T from the father was predicted to abolish the normal splice site, while a novel c.14987G>A (p.Arg4996Gln) variant in cis with another variant, c.6490G>A (p.Ala2164Thr), were both inherited from the mother. These 2 missense variants were predicted to be deleterious by PolyPhen-2 and SIFT. Mutations in TTN can cause AR LGMD type 2J. The growing genetic complexity and emerging phenotypic variability for recessive and dominant TTN variants make the assignment of definitive pathogenicity to many TTN variants difficult and delay our understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of the largest protein known to date.32 In addition to compound heterozygous TTN variants of unknown significance (VUS), patients 36 and 48 each had a heterozygous truncating mutation (a splice site novel mutation c.12742-2A>G and a frameshift mutation c.7062_7063del, respectively) in the NEB gene (table 2).33 Each patient inherited the deleterious NEB allele from the father. Despite the absence of the second mutant allele, muscle biopsy of patient 36 revealed only a nonspecific type 2B fiber atrophy, while patient 48 did show an NM (figure 2F). Patient 54 was suspected of having Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) due to the X-linked EMD gene, of which his mother was a carrier. His cardiac phenotype of complete right bundle branch block may be due to an emerin mutation, but his clinical and pathologic features are not typical of EDMD. The positive emerin staining in the muscle biopsy did not rule out a pathogenic role of this emerin variant.34

Defective genes and diagnostic yields.

In our patient cohort, CM was the most common diagnosis (23/38, 61%), followed by CMD and LGMD. Since parallel analysis of all 236 NMD-related genes in a clinically validated panel is a recent innovative approach to testing, the majority of mutations/variants are “novel.” Theoretically, all missense variants should be classified as VUS until a functional defect can be demonstrated. However, if a VUS is found in patients with a consistent clinical phenotype, family pedigree, and muscle biopsy findings and is predicted to be deleterious, then it is classified as likely pathogenic.

AR disorders account for about half of the cases, while AD cases account for about a quarter. Overall, our NMD gene panel analysis provides a diagnostic yield of 29/35 (83%), which is the highest reported in complex NMD cases in the NGS era.

DISCUSSION

To date, except when using whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome sequencing for novel gene discovery, most NGS studies have focused on a specific NMD category, such as CMD,17 CMyS,18 CMT,19 dystrophinopathy,20 glycogen storage disease,21 or CACTD.22 In this report, we analyzed 236 genes responsible for 10 NMD subcategories. Surprisingly, some patients were found to harbor mutations in genes responsible for disease categories that were not initially considered (IGHMBP2, TCAP, SPTLC2, CACNA1S). This observation confirms that clinical features, muscle imaging, and muscle pathology may be suggestive of a specific diagnosis but that the ultimate diagnosis relies on the identification of mutations in the causative gene(s). Furthermore, some patients are evaluated at a very early or late stage of their disease, when the details of their early clinical course may not be available and the muscle pathology may provide limited information. Under these circumstances, it is very difficult to focus on a specific disease category for the analysis of a single gene or a few genes. Thus, comprehensive NGS analysis of all NMD-related genes provides a cost-effective way to identify causative mutations. Evidence for this is provided by patient 1. The mutation analysis not only established the unexpected diagnosis of HSAN type 1C but also underscored the importance of molecular diagnosis through NGS.35 Similarly, patient 18 was originally diagnosed as having congenital neuropathy, CMT type. The identification of mutations in IGHMBP2 changed the final diagnosis to SMARD1 and further expanded the intercategory phenotype/genotype.36 The identification of IGHMBP2 mutations facilitated the subsequent prenatal diagnosis that resulted in a normal fetus.

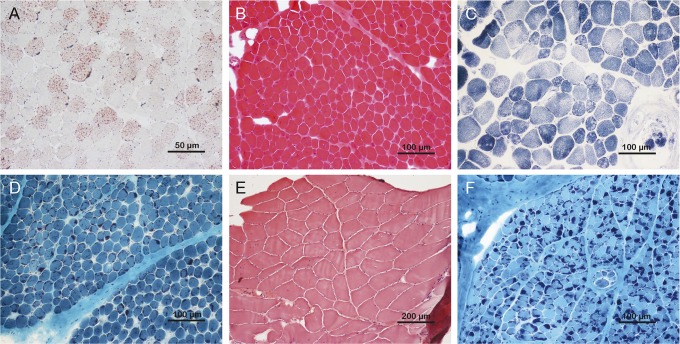

Our comprehensive NGS approach achieves a diagnostic yield of 83% for the highly genetically and clinically complex NMDs. Our capture/NGS approach has at least 2 unique advantages: (1) a comprehensive evaluation of 236 target genes to minimize variations in the coverage depth of individual exons, and (2) deep coverage depth at a mean of >1,000× per base, leaving only ∼0.6% of coding exons containing insufficiently covered (<20×) sequences requiring PCR/Sanger to complete. Thus, consistent coverage of individual exons allows the detection of deletions in >99% of targeted exons.29 This is demonstrated by the identification of a single exon deletion in patient 51 (figure not shown) and by patients 25 and 26 (siblings), in whom both NGS and Sanger sequence analyses identified a heterozygous point mutation (p.Thr3220Ala) in RYR1 (figure 3A), while copy number analysis using the same set of NGS data detected a heterozygous single exon deletion (figure 3B). The deletion was confirmed by using PCR across the deleted exon (figure 3C), showing the reduced size of PCR product (figure 3D).

Figure 3. Confirmation of single exon deletion and point mutation in RYR1 detected by next-generation sequencing.

(A) Sanger sequence for heterozygous c.9658A>G (p.T3220A). (B) Exon 39 heterozygous deletion was detected by copy number variation analysis. (C) Designed primers for exon 39 deletion. Forward primer: F, reverse primer: R, the total length between the primers is 4.3 kb. (D) DNA gel for exon 39 deletion; patients 25 and 26 have extra small fragments on the gel (∼2.7 kb).

Sequence variations in RYR1 and TTN are frequent. This may be related to their relatively large size. Patients with mutations in these 2 genes may exhibit diverse clinical phenotypes and variable muscle pathology. For example, in our patient cohort, both AR and AD RYR1 mutations were identified in muscle biopsies of patients with CCD (patient 3 AR and patient 46 AD), CNM (patient 26), CM with end-stage myopathic change (patient 33), atypical NM (patient M516), and nonspecific findings (patient 1). Patients with RYR1 mutations may also be predisposed to MH. Thus, attention should be paid in anesthetic arrangements to avoid iatrogenic morbidity.37,38 Although NM is one of the most common types of CM,12 we found only 2 patients with AD inheritance (9 and M495), both of whom had ACTA1 mutations.

The TTN gene has not been extensively studied, likely in part due to its size. Sequencing of this gigantic gene (complementary DNA ∼0.1 Mb) only became practical with NGS technology. Therefore, we have just begun to identify and understand its genetic diseases and mechanisms of inheritance. TTN mutations have been identified in patients with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes, including CM, LGMD, and others, with highly variable muscle biopsy findings.1,8,11,39,40 In this study, we have demonstrated the power of target gene capture followed by NGS. This comprehensive approach confirms clinical and pathologic diagnoses when the phenotype is consistent with the causative gene. It also clarifies a patient's underlying genetic cause when a muscle biopsy finding is ambiguous or does not comport with the clinical phenotype. Since the number of genes analyzed is large, it often identifies mutations in genes that may not have been considered in the clinical differential diagnosis, therefore expanding the phenotype/genotype relationship. Although ultimately this comprehensive noninvasive approach is much less expensive and more definitive for molecular diagnosis of the heterogeneous and complex NMDs, muscle pathology and thorough clinical evaluation are still important in the final clinical phenotype/genotype correlation, particularly at the early stage of expanding phenotype/genotype.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AD

autosomal dominant

- AR

autosomal recessive

- BCM

Baylor College of Medicine

- CACTD

carnitine acylcarnitine translocase deficiency

- CCD

central core disease

- CM

congenital myopathy

- CMD

congenital muscular dystrophy

- CMT

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

- CMyS

congenital myasthenic syndrome

- CNM

centronuclear myopathy

- EDMD

Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

- HSAN

hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy

- LGMD

limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

- MH

malignant hyperthermia

- MM

metabolic myopathy

- MTS

myotonic syndrome

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- NM

nemaline myopathy

- NMD

neuromuscular disease

- PFIS

paralytic floppy infant syndrome

- SMARD1

spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1

- VUS

variants of unknown significance

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/ng

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Tian: completed the statistical analysis; performed experiment; analyzed sequence results; and prepared figures and tables for publication. Dr. Liang: study concept and design; analysis and interpretation; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Feng: analyzed results; acquired data; and validated CNV detection using NGS data. Dr. Wang: helped with sequence data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. Dr. Zhang: designed capture library and analytical pipeline; supervised NGS wet bench performance and sequence analysis; and determined the data filtering and variant annotation flowchart. Mr. Chou: study concept and design. Dr. Huang: study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Lam: contributed 2 important cases. Dr. Hsu: study concept and design. Dr. Lin and Ms. Chen: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Wong: interpreted results; designed and supervised the project; and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. Dr. Jong: acquisition of data; study concept and design; analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Tian is an employee of Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories. Dr. Liang reports no disclosures. Dr. Feng is an employee of Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories. Dr. Wang and Dr. Zhang are employees of Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories and are faculty members of BCM with joint appointment at BMGL. Mr. Chou reports no disclosures. Dr. Huang has served on the editorial boards of BMC Bioinformatics, MicroRNA, Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, and Journal of Neuroscience and Neuroengineering and has received research support from NSC. Dr. Lam, Dr. Hsu, Dr. Lin, and Ms. Chen report no disclosures. Dr. Wong is an employee of Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories, is a faculty member of BCM with joint appointment at BMGL, and serves on the editorial board of the journal Mitochondrion. Dr. Jong serves as a consulting editor for Pediatrics and Neonatology, has served on the scientific advisory board for the Asian Oceanian Myology Center, and holds patents for a knockout-transgenic mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy, hydroxyurea treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, methods for diagnosing spinal muscular atrophy, and hnRNP A1 knockout animal model and use thereof. Go to Neurology.org/ng for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan JC, Hamroun D. The 2014 version of the gene table of monogenic neuromuscular disorders (nuclear genome). Neuromuscul Disord 2013;23:1081–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwood FL, Harling C, Chinnery PF, Eagle M, Bushby K, Straub V. Prevalence of genetic muscle disease in Northern England: in-depth analysis of a muscle clinic population. Brain 2009;132:3175–3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad AN, Prasad C. Genetic evaluation of the floppy infant. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;16:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laing NG. Genetics of neuromuscular disorders. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2012;49:33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh RR, Tan SV, Hanna MG, Robb SA, Clarke A, Jungbluth H. Mutations in SCN4A: a rare but treatable cause of recurrent life-threatening laryngospasm. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1447–e1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witting N, Vissing J. Pharmacologic treatment of downstream of tyrosine kinase 7 congenital myasthenic syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnemann CG, Wang CH, Quijano-Roy S, et al. Diagnostic approach to the congenital muscular dystrophies. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:289–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udd B, Vihola A, Sarparanta J, Richard I, Hackman P. Titinopathies and extension of the M-line mutation phenotype beyond distal myopathy and LGMD2J. Neurology 2005;64:636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bevilacqua JA, Monnier N, Bitoun M, et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations cause unusual congenital myopathy with prominent nuclear internalization and large areas of myofibrillar disorganization. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2011;37:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bharucha-Goebel DX, Santi M, Medne L, et al. Severe congenital RYR1-associated myopathy: the expanding clinicopathologic and genetic spectrum. Neurology 2013;80:1584–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeffer G, Elliott HR, Griffin H, et al. Titin mutation segregates with hereditary myopathy with early respiratory failure. Brain 2012;135:1695–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.North KN, Wang CH, Clarke N, et al. Approach to the diagnosis of congenital myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:97–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero NB. Centronuclear myopathies: a widening concept. Neuromuscul Disord 2010;20:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal PB, Joshi M, Marinakis NS, et al. Expanding the phenotype associated with the NEFL mutation: neuromuscular disease in a family with overlapping myopathic and neurogenic findings. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:1413–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peeters K, Chamova T, Jordanova A. Clinical and genetic diversity of SMN1-negative proximal spinal muscular atrophies. Brain 2014;137:2879–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi BO, Koo SK, Park MH, et al. Exome sequencing is an efficient tool for genetic screening of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Hum Mutat 2012;33:1610–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valencia CA, Ankala A, Rhodenizer D, et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis for congenital muscular dystrophy: a clinical PCR-based enrichment and next-generation sequencing panel. PLoS One 2013;8:e53083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abicht A, Dusl M, Gallenmuller C, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: achievements and limitations of phenotype-guided gene-after-gene sequencing in diagnostic practice: a study of 680 patients. Hum Mutation 2012;33:1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ylikallio E, Johari M, Konovalova S, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals further genetic heterogeneity in axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy and a mutation in HSPB1. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22:522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei X, Dai Y, Yu P, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing as a comprehensive test for patients with and female carriers of DMD/BMD: a multi-population diagnostic study. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22:110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Cui H, Lee NC, et al. Clinical application of massively parallel sequencing in the molecular diagnosis of glycogen storage diseases of genetically heterogeneous origin. Genet Med 2013;15:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang GL, Wang J, Douglas G, et al. Expanded molecular features of carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase (CACT) deficiency by comprehensive molecular analysis. Mol Genet Meta 2011;103:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narayanaswami P, Weiss M, Selcen D, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: diagnosis and treatment of limb-girdle and distal dystrophies: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the practice issues review panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology 2014;83:1453–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan JC. The 2012 version of the gene table of monogenic neuromuscular disorders. Neuromuscul Disord 2011;21:833–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Zhang VW, Feng Y, et al. Dependable and efficient clinical utility of target capture-based deep sequencing in molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:6213–6223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7:248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, et al. ACMG recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: Revisions 2007. Genet Med 2008;10:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng Y, Chen D, Wang GL, Zhang VW, Wong LJ. Improved molecular diagnosis by the detection of exonic deletions with target gene capture and deep sequencing. Genet Med 2015;17:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kondo E, Nishimura T, Kosho T, et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations in a patient with severe congenital nemaline myopathy with ophthalomoplegia identified through massively parallel sequencing. Am J Med Genet A 2012;158A:772–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ke Q, Luo B, Qi M, Du Y, Wu W. Gender differences in penetrance and phenotype in hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Muscle Nerve 2013;47:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evila A, Vihola A, Sarparanta J, et al. Atypical phenotypes in titinopathies explained by second titin mutations. Ann Neurol 2014;75:230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehtokari VL, Kiiski K, Sandaradura SA, et al. Mutation update: the spectra of nebulin variants and associated myopathies. Hum Mutat 2014;35:1418–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ura S, Hayashi YK, Goto K, et al. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy due to emerin gene mutations. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1038–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotthier A, Auer-Grumbach M, Janssens K, et al. Mutations in the SPTLC2 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase cause hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type I. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porro F, Rinchetti P, Magri F, et al. The wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes of spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci 2014;346:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larach MG, Brandom BW, Allen GC, Gronert GA, Lehman EB. Malignant hyperthermia deaths related to inadequate temperature monitoring, 2007–2012: a report from the North American malignant hyperthermia registry of the malignant hyperthermia association of the United States. Anesth Analg 2014;119:1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stowell KM. DNA testing for malignant hyperthermia: the reality and the dream. Anesth Analg 2014;118:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chauveau C, Bonnemann CG, Julien C, et al. Recessive TTN truncating mutations define novel forms of core myopathy with heart disease. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:980–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasli N, Bohm J, Le Gras S, et al. Next generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases. Acta Neuropathol 2012;124:273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.