Abstract

BACKGROUND

Subjective memory complaints are common in aged persons, indicating an increased, but incompletely understood, risk for dementia.

Objective

To compare cognitive trajectories and autopsy results of individuals with subjective complaints after stratifying by whether a subsequent clinical dementia occurred.

DESIGN

Observational study.

SETTING

University of Kentucky cohort with yearly longitudinal assessments and eventual autopsies.

PARTICIPANTS

Among 516 patients who were cognitively intact and depression-free at enrollment, 296 declared a memory complaint during follow-up. Among those who came to autopsy, 118 died but never developed dementia, while 36 died following dementia diagnosis.

MEASUREMENTS

Cognitive domain trajectories were compared using linear mixed models adjusted for age, gender, years of education and APOE status. Neuropathological findings were compared cross-sectionally after adjustment for age at death.

RESULTS

While the groups had comparable cognitive test scores at enrollment and the time of the first declaration of a complaint, the group with subsequent dementia development had steeper slopes of decline in episodic memory and naming but not fluency or sequencing. Autopsies showed the dementia group had more severe Alzheimer pathology and a higher proportion of subjects with hippocampal sclerosis of aging and arteriolosclerosis, whereas the non-demented group had a higher proportion expressing primary age related tauopathy (PART).

CONCLUSIONS

While memory complaints are common among the elderly, not all individuals progress to dementia. This study indicates that biomarkers are needed to predict whether a complaint will lead to dementia if this is used as enrollment criteria in future clinical trials.

Keywords: Subjective memory complaints, impairment status, cognitive trajectories, neuropathology

Introduction

Subjective memory complaints (SMCs) are a common, non-specific symptom among aged individuals. These complaints place an older individual at a higher risk for future cognitive impairment including the clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia (1–4). Recent research indicates that dementia, when observed, generally occurs five or more years after the first declaration of an SMC (5). However, much work is required to better track the changes in cognition before and after this declaration.

The relationship between an SMC and future cognitive decline is much weaker in studies with short follow-up length, therefore yielding conflicting results (6,7). In longer studies (at least 5 years of follow-up), subjects with an SMC have lower baseline scores and steeper decline in immediate memory and delayed recall when compared to non-SMC subjects (8–10). However, the effect sizes are often modest. Depression is known to be one possible confounding effect for SMC and likely affects cognition.

The purpose of this study was to examine the cognition of a cohort of initially depression-free individuals both before and after the declaration of an SMC by stratifying these individuals on their eventual outcome: conversion to dementia versus death without any clinical cognitive impairment. The large difference we observed between the cognitive profiles of the two groups illustrates the importance of extended longitudinal follow-up, i.e., knowing each individual’s eventual course to the fullest extent.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects in this study are 154 participants in the longitudinal cohort known as the Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies (BRAiNS) cohort (11) at the University of Kentucky’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK-ADC). Subjects in this cohort were enrolled prior to 2005, depression free and cognitively intact at enrollment, underwent at least two annual cognitive assessments, and agreed to brain donation upon death. In addition, this particular subset of participants expressed an SMC by affirmatively answering “yes” to the question “Have you noticed any changes in your memory since the last visit?” at some point during the study. Participants were followed annually and later experienced either: a clinical diagnosis of dementia or death without any cognitive impairment (including MCI). We did not analyze subjects with MCI since only 9 BRAiNS subjects who declared an SMC prior to cognitive impairment died with an MCI diagnosis; this subset is not considered in this study. All subjects came to autopsy.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board approved all research activities, and each participant gave written informed consent.

Cognitive Assessments

At each visit, participants were administered a neuropsychological test battery summarized here in four cognitive domains: 1) episodic memory (Consortium to Establish a Registry in Alzheimer’s Disease [CERAD] word list total, CERAD word list delayed recall, and Weschler’s Logical Memory Form 1); 2) fluency (Animal Naming and Controlled Oral Word Association Test or COWAT); 3) confrontation naming (CERAD 15-item Boston Naming Test); and 4) sequencing (Trail Making Tests A, B, and the difference B minus A). We summarized each cognitive domain as a Z score as follows: for each instrument in the battery, baseline scores were regressed on age, gender, years of education, and APOE 4 carrier status (any 4 allele = 1, no 4 alleles = 0). We then normed each test score thereafter using these results (predicted mean score was subtracted from the observed score and the difference was divided by the model mean squared error) to generate Z scores. To create these norms we used the baseline scores of all 531 subjects enrolled in BRAINs prior to 2005 with at least two follow-up visits regardless of their subsequent SMC declaration. Results were then factor anlayzed using principal components to yield the four domains studied here. The Z scores for each test in a given cognitive domain were then averaged to create a domain Z score.

Cognitive Diagnosis

Presence of dementia was determined by DSM-IV criteria (12). We considered participants cognitively intact if they were not demented, did not have MCI according to the Second International Working Group criteria (13), and did not have functional impairments. Diagnoses were made by an expert consensus group including neuropsychologists, neurologists, and psychometrists.

Neuropathology

Research volunteers who came to autopsy from UK-ADC (14) were the basis for the study. Neuropathological evaluations were performed as described previously in detail (15). Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic changes (ADNC), Lewy body disease, hippocampal sclerosis of aging (HS-Aging) pathologies were as described using criteria as defined in recent consensus papers (16,17) and UK-ADC papers (18,19). Notably, we previously reported that the cognitive impact of unilateral HS-Aging was comparable to that of bilaterally detected HS-Aging, so our dichotomous “hippocampal sclerosis” parameter includes either unilateral or bilateral HS-Aging cases (19). We operationalized Lewy body disease as positive if the subject met the McKeith et al. (20) criteria for diffuse Lewy body pathology of a severity to indicate either “Intermediate” or “High” likelihood of contributing to a DLB clinical syndrome. Additional cerebrovascular pathology (CVP) measures in the UK-ADC cohort included infarct counts, semiquantitative ratings of atherosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, micro-infarcts, lacunar infarcts, pale infarcts, arteriolosclerosis, and cortical laminar necrosis as previously described (21). For arteriolosclerosis, we considered cases positive if mild, moderate, or severe arteriolosclerosis was identified at autopsy. Finally, PART cases have symptoms that usually range from normal to amnestic cognitive changes and are characterized by temporal lobe atrophy and tauopathy without evidence of Aβ accumulation (22).

Time Scale

The subjects in this study represent a subset from a recent larger study (n = 531) on the risk factors associated with an SMC and the subsequent events of dementia and MCI (5). That study showed that on average the SMC was first reported 5.9 to 8.3 years post enrollment, depending on risk factors, and that the terminating events of dementia and death without an impairment occurred on average 11.0 and 16.8 years post enrollment. Since most SMC subjects had cognitive assessments both before and after the declaration of an SMC, the time scale was set to 0 at the age at which the SMC declaration was first made.

Statistical Analysis

The two SMC groups-terminal event dementia and death without a cognitive impairment-were compared on demographics, risk factors, baseline cognitive scores, and scores at the time of SMC declaration by using two sample t-tests for interval level response and chi-square tests for categorical responses. We used a linear mixed model (LMM) with a linear response over time to conduct the regression of Z scores versus time for each SMC subgroup, with random intercept and slope terms per subject and covariates baseline age, gender, APOE 4 carrier status, and years of education. We used logistic regression models adjusted for age at death to compare neuropathology findings between groups.

Results

The 154 SMC subjects were stratified into two groups by outcome: dementia (23.5%) and death without cognitive impairment (76.5%). The groups were comparable on all self-reported baseline characteristics, demographics, and APOE 4 carrier status (Table 1), except for gender since 72.2% of those who became demented were female compared to 53.8% of those who died without any cognitive impairment (P = 0.054) and use of hormone replacement therapy (P = 0.066 by Fisher’s exact test). Gender is a well-known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and, as shown in (5), baseline use of hormone replacement therapy significantly decreases the time to dementia onset. The groups also differed on smoking at baseline, with the no dementia group having 11.9% smokers compared to none in the dementia group (P = 0.041 by Fisher’s exact test). Smoking is a risk factor for early death in this cohort (5).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by SMC outcome group

| Baseline Characteristics | Dementia n = 36 | Death without Impairment n = 118 |

Total n = 154 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± st. dev.) | 77.3 ± 5.4 | 77.6 ± 7.2 | 77.5 ± 6.8 | 0.82 |

| Years education (mean ± st. dev.) | 15.8 ± 2.0 | 16.1 ± 2.4 | 16.1 ± 2.3 | 0.49 |

| Female (%) | 72.2 | 54.2 | 58.4 | 0.055 |

| APOE 4 carrier (%) | 36.1 | 26.3 | 28.6 | 0.25 |

| Family history of dementia (%) | 41.7 | 29.7 | 32.5 | 0.18 |

| Ever smoke (%) | 47.2 | 57.6 | 55.2 | 0.27 |

| Former smoker (%) | 47.2 | 45.8 | 46.1 | 0.88 |

| Baseline smoker (%) | 0 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 0.041 |

| Type II Diabetes (%) | 2.8 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 0.30 |

| BMI > 25 (%) | 33.3 | 34.7 | 34.4 | 0.89 |

| High blood pressure (%) | 27.8 | 42.4 | 39.0 | 0.12 |

| Hormone replacement therapy (%) | 22.2 | 6.8 | 10.4 | 0.01 |

We also compared the outcome groups on mean baseline cognitive domain scores, and none of these were found to be statistically significant (Table 2). In addition, the groups were compared at the time an SMC was first declared and were found to be different on episodic memory (−0.15 ± 1.06 for dementia versus +0.24 ± 0.87 for death without impairment, P = 0.05) due to an overall increase in scores between baseline and time of SMC declaration in those who eventually died without an impairment.

Table 2.

Mean factor scores at baseline by SMC outcome group adjusted for age, gender, years education

| Cognitive Domain |

Dementia | Death without impairment |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic memory | + 0.02 ± 0.82 | + 0.06 ± 0.75 | 0.79 |

| Naming | + 0.24 ± 0.73 | + 013 ± 0.91 | 0.46 |

| Fluency | + 0.08 ± 0.63 | − 0.12 ± 0.83 | 0.13 |

| Sequencing* | + 0.27 ± 0.74 | + 0.12 ± 0.67 | 0.48 |

these scores are missing on 2 Dementias and 10 Deaths

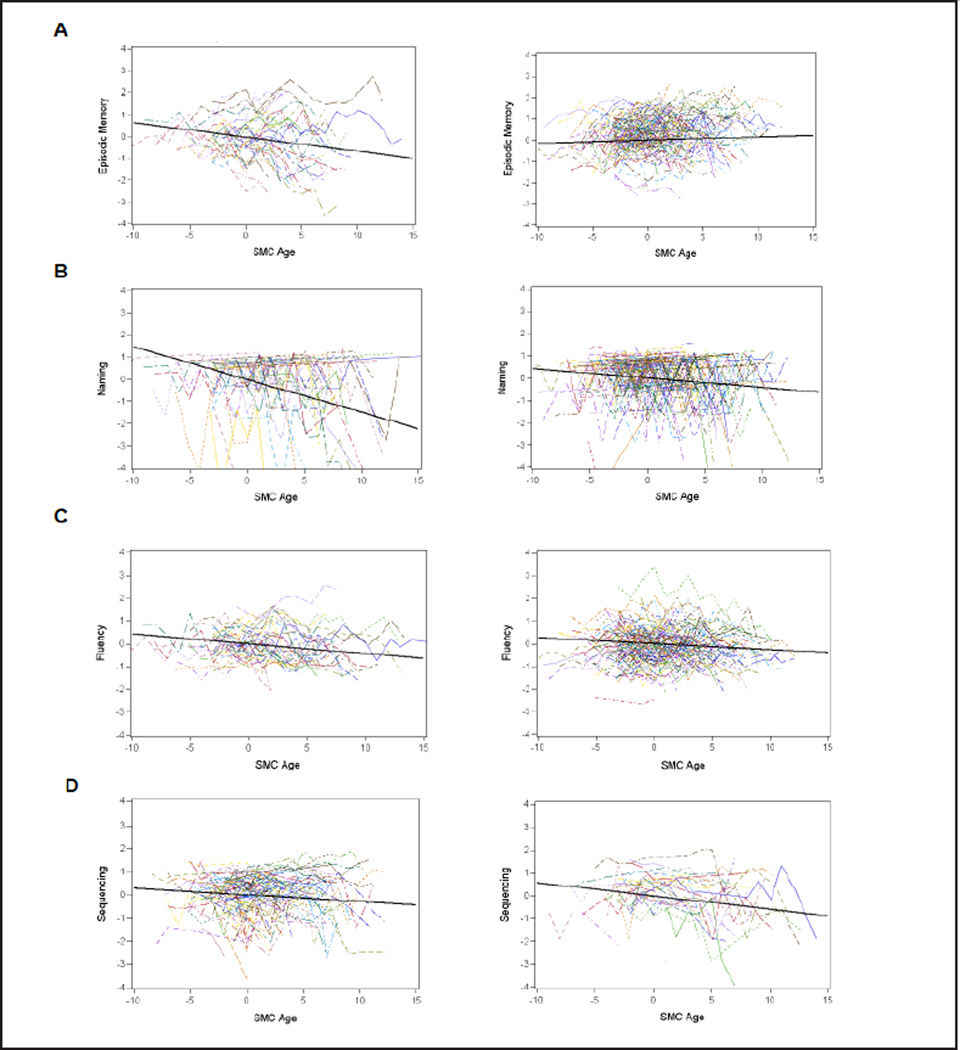

Fitting the LMM for each cognitive domain showed that scores decreased significantly for each outcome group across time for all cognitive domains considered (Table 3 and Figure 1). The exception was episodic memory for the death without impairment outcome group where the scores increased linearly across time. A comparison of the slopes between outcome groups showed significance for episodic memory and naming, where the dementia group declined significantly faster than the death outcome group.

Table 3.

Mean slope (and standard error) for each SMC outcome group by cognitive domain

| Dementia | Death without impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Domain | Slope | s.e. | Slope | s.e. | P value |

| Episodic memory | −0.065 | 0.016 | +0.014 | 0.0096 | <.0001 |

| Naming | −0.148 | 0.026 | −0.042 | 0.017 | 0.0006 |

| Fluency | −0.043 | 0.012 | −0.026 | 0.0073 | 0.22 |

| Sequencing | −0.058 | 0.017 | −0.029 | 0.012 | 0.18 |

Figure 1.

Spaghetti plots by SMC group and accompanying slope of decline as determined by the LMM: panels: A Episodic memory, B Naming, C Fluency, and D Sequencing (dementia on the left and death without impairment on the right)

A comparison of neuropathology findings appears in Table 4, where significance was set at 0.01 due to the number of endpoints examined. As expected, those who became demented had more severe AD pathology ratings (P < 0.0001). In addition, these individuals were more likely to have an HS-Aging pathological diagnosis and arteriolosclerosis consistent with recent reports (17, 18). Part of this is age related since the demented individuals died later (mean age at death 91.8 ± 3.4 versus 86.6 ± 7.4, P = 0.0002). On the other hand, those who died without impairment were more likely to have PART (P = 0.0030).

Table 4.

Comparison of autopsy findings by SMC outcome group

| Percent with pathology | Dementia | Death w/o impairment | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD pathology | < 0.0001 | ||

| None | 2.8 | 25.4 | |

| Low | 19.4 | 37.5 | |

| Intermediate | 61.1 | 35.6 | |

| High | 16.7 | 1.7 | |

| Hippocampal Sclerosis | 22.2 | 1.7 | 0.0037 |

| Intermediate Diffuse Lewy Body Disease | 11.1 | 5.9 | 0.40 |

| Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy | 55.6 | 52.5 | 0.98 |

| Vascular Pathologic Diagnosis | 38.9 | 19.5 | 0.055 |

| Large artery cerebral infarcts | 80.6 | 83.0 | 0.81 |

| Cortical microinfarcts | 75.0 | 72.0 | 0.70 |

| PART | 11.1 | 41.5 | 0.0030 |

| Hemorrhages | 94.4 | 88.1 | 0.32 |

| Arteriolosclerosis* | 88.9 | 39.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Macro infarcts | 25.0 | 22.0 | 0.83 |

| Gross infarcts | 44.4 | 34.7 | 0.46 |

| Hemorrhagic infarcts | 2.8 | 13.6 | 0.083 |

| Lacunar infarcts | 22.2 | 21.2 | 0.81 |

| Micro infarcts | 33.3 | 49.1 | 0.061 |

| Pale infarcts | 33.3 | 18.6 | 0.20 |

measurement missing on 2 deaths;

all P values are adjusted for age at death

Discussion

Subjective memory complaints are common and are considered to be a risk factor for a future dementia diagnosis. However, not all complainers develop dementia. Therefore it is of interest to determine if the trajectory of these patients differs from those who go onto develop dementia. While those participants with SMCs who died without cognitive impairment had an initial neuropsychological profile similar to those who proceeded to dementia, those who did proceed declined at a much faster rate in the cognitive domains of episodic memory and naming but not in fluency or sequencing. At autopsy, those who did not decline died on average 5 years earlier and showed fewer signs of brain pathology involving HS-aging and arteriosclerosis but showed more evidence of PART. As far as we know, this is the first study to follow a cohort with SMCs who failed to convert to dementia and to compare them with a cohort with SMCs who developed dementia.

One phenomenon that is underscored by our results is that multiple brain diseases underlie progression from SMC to dementia. There is increasing awareness that the concepts of “dementia” and Alzheimer’s disease should not be conflated. Whereas we report evidence to indicate that the high-morbidity plaque-and-tangle disease (Alzheimer’s) is often the culprit, HS-Aging and small vessel brain disease are also greatly enriched among the dementia cases at autopsy. It is intriguing that HS-Aging pathology has a strong association with arteriolosclerosis, and these comorbid pathologies may constitute an underappreciated brain disease that afflicts the “oldest-old”(21, 23). It is equally intriguing that those who expressed an SMC but did not progress to dementia had more PART pathology, which is a newly delineated neuropathology (22).

While the between-group difference in episodic memory scores was expected, those who did not develop dementia improved their age-adjusted memory scores over time, presumably reflecting a practice effect (24), while those who progressed to dementia experienced a significant decline in episodic memory. While both groups declined in the naming, fluency and sequencing domains, the decline was less pronounced for those who did not progress, although only the naming result attained statistical significance. These results show that subjects who are unimpaired but declare an SMC may be a quite heterogeneous group, which is an important confounder relative to the common practice of studying SMCs as a unitary group. This is a substantial proportion of SMCs since 127 of 296 subjects (42.9%) who declared an SMC in our cohort died without any clinically detectable cognitive impairment (118 of these who came to autopsy are in this study). This finding compares favorably with Reisberg et al. (4), who studied a cohort of 200 subjects with normal cognition and SMC and found that among the 166 complainers (with 6.8 year of follow-up on average) 45.8% remained free of MCI or dementia.

Observed differences in cognitive trajectories associated with SMC depend on the length of follow-up and participant characteristics. In the DESCRIPA study Visser et al. (7) used cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling to classify unimpaired subjects with SMCs into two subgroups: those who were CSF amyloid-positive (n = 31) and those who were not positive (n=29). They observed no differences during follow-up between these subgroups on Z scores for tests of memory and cognition. While these results contrast with those presented here, the subjects in the Visser study were followed for only 2.5 years on average (versus 10.2 years here) and were eleven years younger at baseline (66.0) than those followed in this study.

Several approaches have been suggested for possible early detection of those SMC reporters who will not progress to impairment. In a study of 44 patients with SMCs but no cognitive deficit, Prichep et al. (25) found that the subset of 27 subjects who declined during 7–9 years of follow-up had increases in baseline theta power and slowing of mean frequency on quantitative electroencephalograms when compared to those who did not decline. In a pooled item response theory analysis using data from four community-based studies, complainers who scored low on the subjective cognitive complaints severity scale endorsed items related to word retrieval, while those who scored high on the severity scale endorsed items related to non-episodic memory changes, decline in comprehension, judgment, executive function, praxis, procedural memory, and social behavior changes (26). However, follow-up to determine if the severity scale is related to future cognitive impairments is needed. Finally, in a study of 127 persons with an SMC, low CSF Aβ42 was a predictor of progression to clinical cognitive impairment (27).

Limitations of this study include the uneven attrition of subjects from the original cohort of 531 subjects discussed in Kryscio et al. (5). Briefly, 296 subjects declared an SMC during follow-up and of these only 198 have terminal events defined as either incident dementia (n=70), death without dementia (n= 127), or MCI to death (n=9). To enter the current study a person who declared an SMC had to have at least two cognitive assessments and had to come to autopsy; this standard was met adequately by 118 of the 127 deaths without an impairment subgroup but inadequately by 36 of the 70 demented (9 had autopsies but no available cognitive assessments and 26 had no autopsy). In addition, an SMC only required a positive response to the question ”Have you noticed any changes in your memory since the last visit?”. In this study the dementia group complained more consistently about their memory change on visits after the first SMC declaration: 5.3 ± 2.9 versus 2.7 ± 2.4 annual visits (P < 0.0001). A more probing question or set of questions might have changed the composition of the two subgroups being compared here. Alternatively, recent evidence suggests corroboration of a complaint by an informant foretells a greater decline in cognitive performance when compared to a self-complaint only (28).

Three other potential limitations were suggested by a reviewer. Since the subjects who died without an impairment died five years earlier than subjects who became demented before dying, we determined if age of death could be a factor by re-constructing Tables 2–4 to include only the 39 oldest subjects in the death without dementia group. Although the latter subset died three years later than the demented subjects, the results reported in Tables 2–4 did not change (data not shown). In addition, the results did not change when the subjects who declared a SMC and then incurred a MCI before dying were added to the dementia subgroup.

A third consideration was to include a control group consisting of all those subjects in the cohort followed by Kryscio et al. (5) who were cognitively unimpaired and declared no subjective complaints at baseline or during follow-up (56 subjects in this normal death subgroup came to autopsy). This normal control subgroup was similar to the subjective memory complainers who did not become demented in all entries of Tables 1–4 with two exceptions: in Table 2 the normal control subgroup had a significantly higher mean fluency score (P = 0.011), and in Table 4 the normal control subgroup had slightly less severe AD pathology (P = 0.045). To streamline the analyses, this normal subgroup was not included in the manuscript. The implication is that at baseline and during follow-up the non-demented subgroup of subjective memory complainers behaved like controls who did not express an SMC, with similar pathological findings upon autopsy. This implies that PART was not specific to the non-demented subjective complainers since non-demented, non-complainers expressed a similar proportion of cases with PART (57.1% versus 41.5%). However, referring to Figure 2 of (5), the subjective complainers had increased neuritic plaque counts in the medial temporal and neocortex brain regions when compared to this normal subgroup. In addition, the SMC non impaired subgroup showed a trend toward increased neurofibrillary tangle counts in the medial temporal cortex when compared to the non SMC non impaired subgroup (means: 11.7 ± 17.4 versus 7.8 ± 10.5, P = 0.054) which together with the previous increased plaque counts indicates that the two subgroups likely have different underlying pathology.

In summary, this manuscript reported on a group of research volunteers who expressed subjective memory complaints during follow-up in an observational study and showed that this is a heterogeneous group of subjects: some subjects progressed to dementia, while many others did not. Further, there are different pathologically defined diseases that underlie this progression. This has implications for designing enriched prevention trials that enroll baseline cognitively intact individuals with SMCs. While recruiting participants with SMC may decrease the minimum sample size of a prevention trial, further characterization is needed to delineate those who will develop dementia during follow-up from those who will not if savings are to be realized. And for those who will decline, better methods are required for accurate diagnosis of underlying disease. This would allow for stratification into risk groups as suggested for dementia prevention trials enrolling mildly impaired subjects (29).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was partially funded with support from the following grants to the University of Kentucky’s Center on Aging: R01 AG038651, P30 AG028383, and AG019241 from the National Institute on Aging, as well as a grant to the University of Kentucky’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, UL1TR000117, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards: The study protocol was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board in addition to Institutional Review Boards at each study site. All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Geerlings MI, Jonker C, Bouter LM, Ader HJ, Schmand B. Association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognition. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):531–537. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J. Am. Geriatr.. Soc. 2004;52(12):2045–2051. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, et al. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):414–422. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, Leng L, Zhu W. Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dementia. 2010;6(10):11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Cooper GE, et al. Self reported memory compliants: implications from a longitudinal study with autopsies. Neurology. 2014;83(15):1359–1365. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flicker C, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. A longitudinal study of cognitive function in elderly persons with subjective memory complaints. J. Am. Geraitr.. Soc. 1993;41(10):1029–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser PJ, Verhey F, Knol DL, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of CSF markers of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in patients with subjective cognitive impairment or mood cognitive impairment in the DESCRIPA study: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8:619–627. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Henderson AS. Memory complaints as a precursor of memory impairment in older people: a longitudinal analysis over 7–8 years. Psychol. Med. 2001;31(3):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dik MG, Jonker C, Comijs HC, et al. Memory complaints and APOE-4 accelerate cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2217–2222. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohman TJ, Beason-Held LL, Lamar M, Resnick SM. Subjective cognitive complaints and longitudinal changes in memory and brain function. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(1):125–130. doi: 10.1037/a0020859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitt FA, Nelson PT, Abner E, et al. University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown Healthy Brain Aging Volunteers: Donor characteristics, Procedures and Neuropathology. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:724–733. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Ed. Washington, DC: American Psyciatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto, et al. Mild cognitive impairment—beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Int Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(12):1136–1146. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c5efb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(1):66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Lin Y, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features. Brain. 2011;134(5):1506–1518. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Consortium on DLB. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neltner JH, Abner EL, Baker S, et al. Arteriolosclerosis that affects multiple brain regions is linked to hippocampal sclerosis of ageing. Brain. 2014;137(1):255–267. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):755–766. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews M, Abner EL, Caban-Holt A, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA. CERAD practice effects and attrition bias in a dementia prevention trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(7):1115–1123. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prichep LS, John ER, Ferris SH, et al. Prediction of longitudinal cognitive decline in normal elderly with subjective complaints using electrophysiological imaging. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27:471–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snitz BE, Yu L, Crane PK, Chang C-CH, Hughes TF, Ganguli M. Subjective cognitive complaints of older adults at the population level: an item response theory analysis. Alzheimer Di Assoc Disord. 2012;26(4):344–351. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Harten AC, Visser PJ, Pijnenburg YAL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is the best predictor of clinical progression in patients with subjective complaints. Alzheimers Dementia. 2013;9(5):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gifford KA, Liu d, Carmonac H, et al. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondmented older adults. Alzheimers Dementia. 2014;10(3):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holland D, McEvoy LK, Desikan RS, Dale AM. Enrichment and stratification for predementia Alzheimer disease clinical trials. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]