Abstract

During development GABA and glycine synapses are initially excitatory before they gradually become inhibitory. This transition is due to a developmental increase in the activity of neuronal potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 (KCC2), which shifts the chloride equilibrium potential (ECl) to values more negative than the resting membrane potential. While the role of early GABA and glycine depolarizations in neuronal development has become increasingly clear, the role of the transition to hyperpolarization in synapse maturation and circuit refinement has remained an open question. Here we investigated this question by examining the maturation and developmental refinement of GABA/glycinergic and glutamatergic synapses in the lateral superior olive (LSO), a binaural auditory brain stem nucleus, in KCC2-knockdown mice, in which GABA and glycine remain depolarizing. We found that many key events in the development of synaptic inputs to the LSO, such as changes in neurotransmitter phenotype, strengthening and elimination of GABA/glycinergic connection, and maturation of glutamatergic synapses, occur undisturbed in KCC2-knockdown mice compared with wild-type mice. These results indicate that maturation of inhibitory and excitatory synapses in the LSO is independent of the GABA and glycine depolarization-to-hyperpolarization transition.

Keywords: potassium-chloride cotransporter, inhibitory plasticity, auditory brain stem development

in the adult brain inhibitory synapses releasing GABA or glycine elicit postsynaptic hyperpolarizations, but early in development GABA and glycine are depolarizing and can act as excitatory neurotransmitters (Cherubini et al. 1991; Kandler and Friauf 1995a; Kullmann and Kandler 2001; Obata et al. 1978). GABAA and glycine receptors, the main receptors mediating fast inhibitory responses in the central nervous system, are ligand-gated chloride channels, and in mature neurons their activation leads to an influx of chloride due to a low intracellular chloride concentration and a chloride reversal potential (ECl) negative to the resting membrane potential (Vrest). In immature neurons, however, the intracellular chloride concentration is high, resulting in an ECl more positive than Vrest, which upon activation of GABAA or glycine receptors causes an efflux of chloride and membrane depolarization. The intracellular chloride concentration of neurons is determined by the relative activity of inward and outward chloride transporters. In immature neurons, chloride inward transporters dominate, with the sodium-potassium-chloride transporter NKCC1 being the most prominent (Kaila et al. 2014). While the expression or activity of NKCC1 decreases with maturation, the expression and/or activity of outward transporters, most prominently potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 (KCC2), increases, causing a gradual negative shift of ECl.

A number of studies have provided evidence that the depolarizing effect of GABA and glycine plays an important regulatory role in all stages of brain development from neuronal proliferation to the fine-tuning of neuronal circuits (Ben-Ari 2014; Wang and Kriegstein 2009). GABAergic depolarizations regulate proliferation of neuronal progenitors and neuronal differentiation (Owens and Kriegstein 2002a, 2002b; Reynolds et al. 2008; Tozuka et al. 2005; Young et al. 2012), cortical interneuron migration (Bortone and Polleux 2009; Ge et al. 2006), dendritic growth (Cancedda et al. 2007; Ge et al. 2006; Pfeffer et al. 2009; Young et al. 2012), early network activity (Kasyanov et al. 2004; Pfeffer et al. 2009), and the maturation of excitatory and inhibitory synapses (Akerman and Cline 2006; Chudotvorova et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006; Wang and Kriegstein 2008). Whether the transition to hyperpolarization regulates later processes in the maturation or refinement of synapses and neuronal circuits remains poorly understood. Several observations, however, provide correlative support for this possibility. For example, in the somatosensory cortex, the transition from GABA depolarization to hyperpolarization coincides with the functional recruitment of GABAergic circuits as evidenced by profound increase in the strength of unitary GABAergic connections and of the thalamocortical drive of fast-spiking interneurons (Daw et al. 2007). In an inhibitory auditory brain stem pathway, the pathway from the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) to the lateral superior olive (LSO), the period of elimination and strengthening MNTB-LSO connection coincides with the period when GABA and glycine transition to become hyperpolarizing (Balakrishnan et al. 2003; Kandler and Friauf 1995a; Kim and Kandler 2003; Kullmann and Kandler 2001).

The LSO is a binaural nucleus in the auditory brain stem of mammals that encodes interaural sound level differences, a major cue for determining the azimuthal direction of incoming sound (Tollin 2003). LSO neurons are excited by sound at the ipsilateral ear, via a glutamatergic pathway from the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus (CN), and are inhibited by sound at the contralateral ear, via GABAergic and/or glycinergic input from the medial MNTB. These converging inputs to the LSO are tonotopically organized and aligned. During development, both pathways undergo a number of structural and functional changes (Alamilla and Gillespie 2011, 2013; Case et al. 2011; Gillespie et al. 2005; Sanes and Friauf 2000), which are thought to be important steps to increase the precision of tonotopic organization and the proper adjustment of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic strengths, features that are essential for proper sound localization. These maturational changes are especially pronounced in the MNTB-LSO pathway and include a transition in neurotransmitter phenotype (Gillespie et al. 2005; Kotak et al. 1998; Nabekura et al. 2004) and the silencing and strengthening of connections (Hirtz et al. 2012; Kandler et al. 2009; Kim and Kandler 2003; Walcher et al. 2011). Both of these developmental milestones occur during the period when MNTB-LSO synapses transition from being excitatory to being inhibitory (Balakrishnan et al. 2003; Ehrlich et al. 1999; Kakazu et al. 1999; Kandler and Friauf 1995a; Kullmann et al. 2002; Kullmann and Kandler 2001; Shibata et al. 2004), suggesting that the polarity switch of GABA and glycine responses regulates some of these processes.

Mature LSO neurons maintain their low intracellular chloride concentration by KCC2 (Balakrishnan et al. 2003), specifically by the KCC2b isoform, which is the only KCC2 isoform expressed in the auditory brain stem (Markkanen et al. 2014). In the LSO, KCC2 is expressed even while GABA and glycine are still depolarizing (Balakrishnan et al. 2003; Becker et al. 2003), indicating that an increase in KCC2 activity rather than an increase in KCC2 protein levels is the process responsible for the negative shift of ECl (Blaesse et al. 2006). The identity of the chloride inward transporter that is responsible for the positive ECl during the first postnatal week is still unresolved, although the HCO3−/Cl− exchanger AE3, the only chloride inward transporter expressed in the LSO, appears as a promising candidate (Friauf et al. 2011).

In this study we tested the hypothesis that the depolarization-to-hyperpolarization transition regulates maturation and refinement of inhibitory and/or excitatory synapses in the LSO. To address this, we characterized the development of synaptic inputs to LSO neurons in KCC2-knockdown (KCC2-KD) mice, which have a targeted disruption of KCC2 exon 1b and consequently lack ∼92% of KCC2 protein (Woo et al. 2002). Unexpectedly, we found that the maturation of MNTB-LSO and CN-LSO synapses in KCC2-KD mice occurs normally. This indicates that many aspects of synaptic maturation and refinement in the LSO occur independent of a change in the polarity of GABA and glycine responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experimental procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Pittsburgh. The generation of KCC2-KD mice and their genotyping were described previously (Woo et al. 2002).

Slice Preparation

Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (Webster Veterinary) or hypothermia. Brains were harvested and transferred to ice-cold ACSF (composition in mM: 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 5 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, pH 7.4, aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2) with kynurenic acid (1 mM). Coronal brain slices (300–400 μm), containing the LSO, were cut with a vibrating microtome as previously described (Kullmann and Kandler 2001). No differences in minimal and maximal stimulus amplitudes were observed between 300- and 400-μm slices.

Electrophysiology

Whole cell voltage-clamp recordings were made from LSO neurons during stimulation of the MNTB or CN fiber tract with stimulating glass electrodes containing ACSF. Recording electrodes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with intracellular recording electrode solution containing (in mM) 54 d-gluconic acid, 54 CsOH, 56 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 11 EGTA, 0.3 Na-GTP, 2 Mg-ATP, and 5 QX-314, with 0.5% biocytin (pH 7.2, 280 mOsm). Access resistance (<20 MΩ) was compensated by 80% with 10-μs lag with an Axopath 1D amplifier. GABA/glycinergic responses were isolated by the addition of kynurenic acid (1 mM) to the ACSF. Glutamatergic responses were isolated by GABAA receptor (GABAAR) antagonists bicuculline (10 μM; Tocris) or SR95531 (10 μM; Tocris) and glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (1 μM; Sigma). In some experiments, APV (50–100 μM), an NMDA receptor (NMDAR) antagonist, was added to isolate AMPA receptor (AMPAR)-mediated currents. Glycine (5 μM) was added in ACSF to measure NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents. Liquid junction potential (9 mV) was corrected online. Electrical stimuli were delivered by Master 8 and Isoflex (AMPI). For measurements of membrane properties, Cs+ was replaced with K+. The membrane properties of LSO neurons in KCC2-KD mice were not different from those in wild-type (WT) mice at P10-11 [Vrest (mV): −57.6 ± 1.5 (n = 9) for WT, −58 ± 1.5 (n = 11) for KD; input resistance (MΩ): 290 ± 46 (n = 12) for WT, 258 ± 50 (n = 14) for KD; membrane capacitance (pF): 37.3 ± 2.4 (n = 12) for WT, 39.3 ± 2.4 (n = 14) for KD] (P > 0.5 for each measurement).

Minimal stimulation.

Minimal stimulation was adjusted, as previously described (Kim and Kandler 2003, 2010), to obtain a failure rate >50%. Synaptic responses (50–200 times at 0.2 Hz) with an onset latency of <5 ms occurring within a 1-ms window between stimuli were considered responses from a single MNTB fiber input. The mean peak amplitudes of the successful responses were averaged to obtain single-fiber input strength in the MNTB-LSO pathway.

Maximal stimulation.

Electrical stimulation was increased by 100-μA steps until the peak synaptic currents reached steady-state level or decreased slightly. A minimum of 10 maximal input responses at 0.1 Hz were recorded. The number of cells recorded from for each slice was limited to five in order to reduce the slice variation and fiber rundown. With the maximal stimulus paradigm, CN inputs (20–150 stimuli) with stimulation electrodes positioned in the ventral acoustic stria were obtained.

Data acquisition.

Signals were filtered at 2 kHz (Bessel filter, Axoclamp-1D, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and digitized at 10 kHz (Custom LabVIEW acquisition program 5.0, National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Decay time constant analysis.

Decay time constants (τs) were analyzed for the time period from 10% to 90% of the peak amplitudes of the single-fiber responses (with Mini Analysis 6.0.3, Synaptosoft and Clampfit 9.2.0). For decay τ, the τs from a single- and a double-exponential function were compared. If the R2 (goodness of fit) value of a double-exponential fit differed by 1% or more compared with the fit of a single exponential, decay τs from a double-exponential fit were used.

Calcium Imaging

Slices were labeled with the calcium indicator fura-2 AM with a spin labeling procedure (Ene et al. 2007). After a recovery of 15–30 min, brain slices were placed in a microcentrifuge tube (1.5 ml) containing fura-2 AM (100 μM) and centrifuged at 430 g (IEC Clinical Centrifuge, International Equipment) for 15–20 min. After centrifugation, slices were further incubated with 10 μM fura-2 AM for at least 30 min (at room temperature) before imaging acquisition. Ratiometric images (340 nm/380 nm) were acquired with an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE200) equipped with ×10 (NA 0.5) and ×20 (NA 0.75) air objectives using a computer-controlled monochromator (Polychrome II, T.I.L.L. Photonics, Martinsried, Germany). Fluorescence images were acquired at 0.1 Hz with a CCD camera (IMAGO, T.I.L.L. Photonics) and 50-ms periods of excitation alternating between 340 nm and 380 nm (Polychrome II, T.I.L.L. Photonics). Background fluorescence was subtracted with Tillvision (T.I.L.L. Photonics) as described previously (Ene et al. 2003). GABA, glycine, and KCl were bath applied in aerated ACSF via perfusion.

Statistics

Normality of data distribution was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The statistical difference between two groups was compared with an unpaired Student's t-test when normally distributed (parametric test) and with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and Mann-Whitney U-test when nonnormally distributed (nonparametric test).

RESULTS

GABA and Glycine Are Excitatory Neurotransmitters and Increase Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration in LSO Neurons of KCC2-KD Mice at Hearing Onset

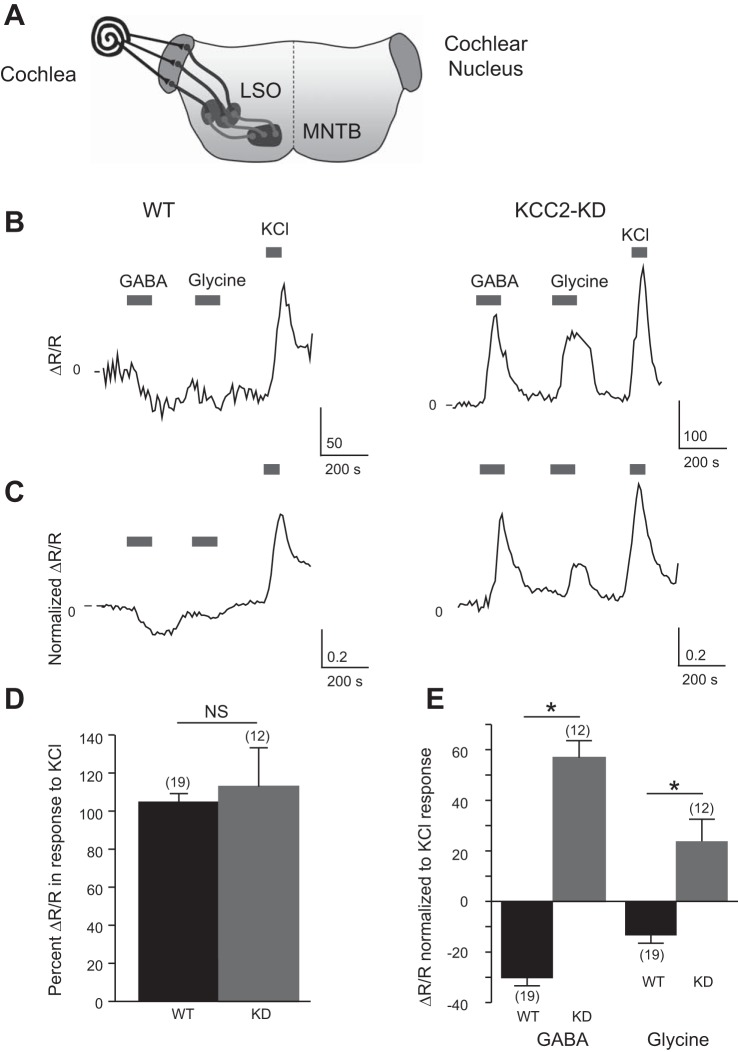

In the LSO, GABA and glycine transition from being depolarizing and eliciting an influx of calcium to being hyperpolarizing and decreasing the intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) around the end of the first postnatal week (Balakrishnan et al. 2003; Ehrlich et al. 1999; Kakazu et al. 1999; Kandler and Friauf 1995a; Kullmann et al. 2002). To verify that genetic deletion of KCC2b in KCC2-KD mice prevents this transition, we measured GABA- and glycine-induced Ca2+ responses in LSO neurons from age-matched WT and KCC2-KD mice. To avoid the inclusion of injured or unhealthy neurons, we restricted our measurements to neurons that showed a robust calcium response to depolarization with KCl (60 mM) (Kullmann et al. 2002). LSO neurons from WT and KCC2-KD mice did not differ in the magnitude of KCl-induced Ca2+ responses [340 nm-to-380 nm fluorescence ratio change (ΔR/R) normalized to mean response of WT mice: 104.6 ± 4.5% for WT, 112.9 ± 20.4 for KCC2-KD, P > 0.1] (Fig. 1, B–D), indicating that deletion of KCC2b did not affect voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) or intracellular calcium buffering. Consistent with previous studies (Kullmann et al. 2002), GABA (2 mM) or glycine (2 mM) never increased [Ca2+]i but slightly decreased [Ca2+]i in P11 WT mice (GABA: −30.4% ± 3.0, glycine: −13.5% ± 3.0; values normalized to KCl responses, n = 19/2 animals) (Fig. 1, B, C, and E), likely due to a hyperpolarization-induced deactivation of L-type calcium channels (Kullmann et al. 2002; Magee et al. 1996; Titz et al. 2003). In contrast, in KCC2-KD mice GABA and glycine increased [Ca2+]i in the majority of LSO neurons tested, with considerable increase of [Ca2+]i comparable to KCl-induced [Ca2+]i (GABA: 56.9 ± 6.7%, glycine: 23.8 ± 8.7%; n = 12/2 animals) (Fig. 1, B, C, and E), indicating that in the LSO of KCC2-KD mice GABA and glycine fail to transit to hyperpolarizing neurotransmitters and remain depolarizing during the second postnatal week.

Fig. 1.

GABA and glycine remain excitatory and increase intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in lateral superior olive (LSO) neurons of KCC2-knockdown (KCC2-KD) mice at P8-11. A: diagram of the auditory brain stem circuitry. LSO neurons receive excitatory glutamatergic synaptic inputs from the cochlear nucleus (CN) and inhibitory synaptic inputs from the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). B: representative traces of the 340 nm-to-380 nm fluorescence ratio (R) change (ΔR/R) of a LSO neuron in wild-type (WT; left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice in response to bath application of GABA (2 mM), glycine (2 mM), and KCl (60 mM). C: average ΔR/R trace of all recorded LSO neurons (normalized to KCl responses) from WT (n = 19, left) and KCC2-KD (n = 12, right) mice. D: % change of ΔR/R in response to KCl (normalized to average ΔR/R KCl response of WT mice) in WT and KCC2-KD mice (n = 19 for WT, n = 12 for KCC2-KD). E: peak ΔR/R in response to GABA and glycine normalized to each cell's KCl response in WT (n = 19) and KCC2-KD (n = 12) mice. *P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test. NS, not significant.

Developmental Strengthening and Elimination of MNTB-LSO Connections Is Not Affected in KCC2-KD Mice

Before hearing onset (P12-14) (Song et al. 2006), the precision of the topographic organization in the MNTB-LSO pathway is increased by silencing most initial MNTB inputs to individual LSO neurons while strengthening remaining connections (Hirtz et al. 2012; Kim and Kandler 2003, 2010; Noh et al. 2010). To test whether any of these refinement processes require the polarity switch of GABA and glycine, we compared the developmental strengthening of single-fiber connections and all MNTB inputs to individual LSO neurons between WT and KCC2-KD mice.

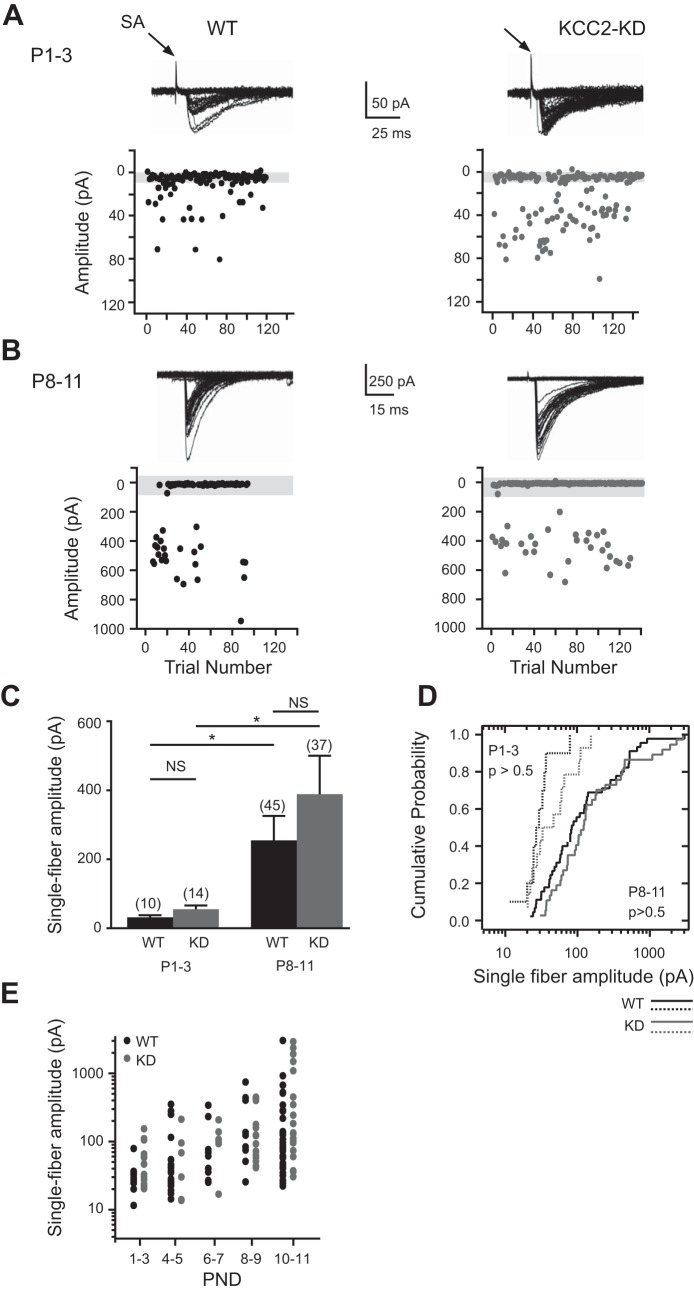

Single-fiber responses were elicited by using minimal stimulation in the presence of kynurenic acid to isolate GABA/glycinergic responses as previously described (Clause et al. 2014; Kim and Kandler 2003). Similar to previous studies, the single-fiber strength of WT mice increased approximately eightfold during the first two postnatal weeks [P1-3: 31.9 ± 5.7 pA (n = 10), P8-11: 254.6 ± 71 pA (n = 45); P < 0.005] (Fig. 2, A–C). In KCC2-KD mice, single-fiber responses increased approximately sevenfold [P1-3: 55.3 ± 10.9 pA (n = 14), P8-11: 388.7 ± 111 pA (n = 37); P < 0.005] (Fig. 2, A–C). There was no significant difference in the amplitude of single-fiber responses between WT and KCC2-KD mice at any age group (Fig. 2, C–E; P > 0.05), indicating that the switch to hyperpolarizing GABA/glycinergic responses is not essential for the strengthening of single-fiber responses in the MNTB-LSO pathway.

Fig. 2.

Developmental increase of single-fiber MNTB-LSO responses elicited by minimal stimulation is similar in WT and KCC2-KD mice. A and B, top: representative traces showing MNTB-LSO single-fiber responses recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV in WT (left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice at P1-3 (A) and P8-11 (B). Bottom: single-fiber response amplitudes as a function of stimulation trial number. Stimulus artifacts (SA) are truncated. C: average single-fiber response amplitudes of WT and KCC2-KD mice at P1-3 (n = 10 for WT, n = 14 for KCC2-KD) and P8-11 (n = 45 for WT, n = 37 for KCC2-KD). *P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test. D: cumulative probability histogram of single-fiber amplitudes from LSO neurons shown in C of WT and KCC2-KD mice at P1-3 (dashed line) and P8-11 (solid line). There was no significant difference between genotypes (P > 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). E: developmental time course of single-fiber amplitudes in WT and KCC2-KD mice as a function of postnatal day (PND).

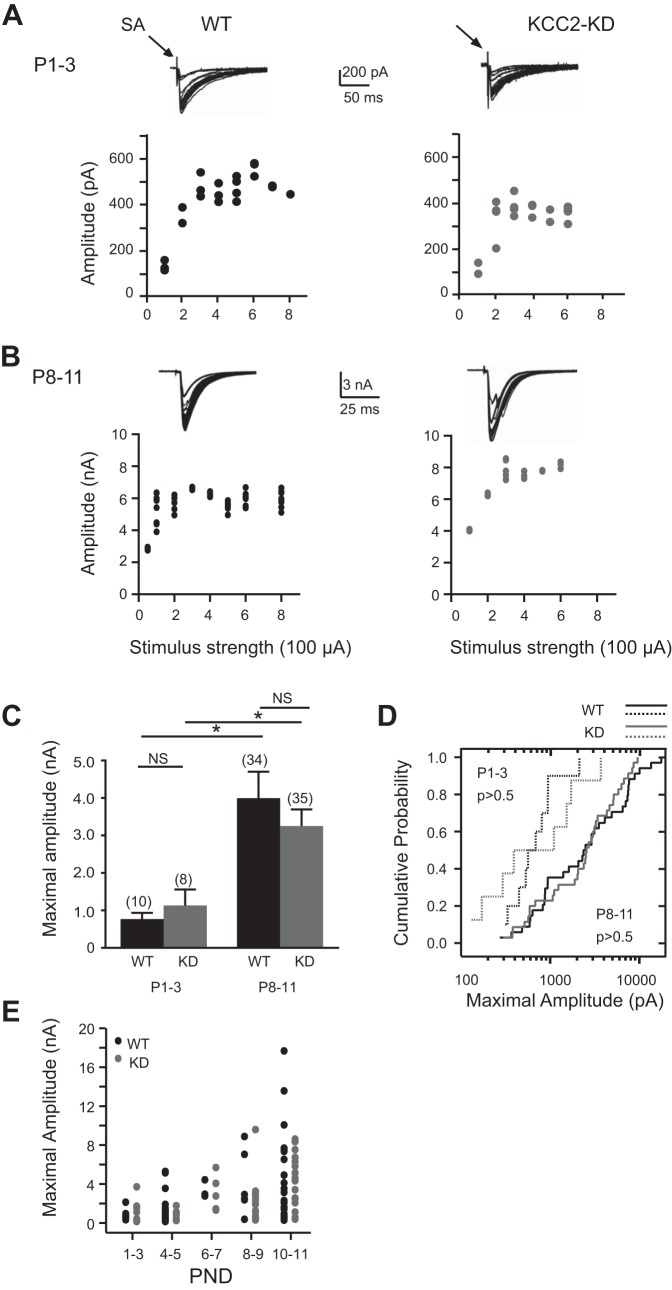

Next we compared the developmental increase of the summed strength of all converging MNTB input by increasing the stimulus intensity to levels that produce maximal response amplitudes (Kim and Kandler 2003, 2010; Noh et al. 2010). Consistent with previous studies, in WT animals the average maximal response amplitude at P1-3 was 0.7 ± 0.2 nA (n = 10) and this value increased to 4.0 ± 0.7 nA at P8-11 (n = 34) (Fig. 3, A and C). In KCC2-KD mice, the average maximal MNTB input was 1.1 ± 0.4 nA at P1-3 (n = 8) and 3.3 ± 0.4 nA at P8-11 (n = 35) (Fig. 3, A and C). The amplitude of maximum responses was not significantly different between WT and KCC2-KD mice at any age group (Fig. 3, C–E; P > 0.5), indicating that the developmental increase in total MNTB synaptic strength onto individual LSO neurons is adjusted independently from the excitatory-inhibitory transition of MNTB-LSO synapses.

Fig. 3.

Developmental increase of maximal MNTB-LSO responses is similar in WT and KCC2-KD. A and B: representative example of the stimulus-response relationship of the maximal MNTB fiber input onto to a single LSO neurons in WT (left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice at P1-3 (A; n = 10 for WT, n = 8 for KCC2-KD) and P8-11 (B; n = 34 for WT, n = 35 for KCC2-KD). Stimulus artifacts are truncated. Maximal amplitude values were derived from the average of at least 10 responses at stimulus strengths with plateaued amplitudes. C: maximal input at P1-3 and P8-11 for WT and KCC2-KD mice. *P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U-test). D: cumulative probability histogram of maximal responses in WT and KCC2-KD mice at P1-3 (dashed line) and P8-11 (solid line). Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests indicate no differences between genotypes at the same age group. E: developmental time course of maximal fiber input in WT and KCC2-KD mice as a function of postnatal day.

The relationship between the strength of single-fiber and maximal synaptic input can be used to estimate the number of fibers converging onto a single LSO neuron (convergence ratio) (Clause et al. 2014; Kim and Kandler 2003). In WT mice, the convergence ratio decreased from ∼24:1 at P1-3 to 15:1 at P8-11, which is in line with previously published results (Clause et al. 2014; Kim and Kandler 2003). Similar to WT mice, convergence ratios of KCC2-KD mice were reduced from 20:1 at P1-3 to 8:1 at P8-11 and were not significantly different from those of WT mice (P > 0.05). Taken together, the similarity in the strengthening of single and maximal MNTB fiber inputs along with similar reductions in the convergence ratios in the MNTB-LSO pathway between WT and KCC2-KD mice (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) suggest that the GABA/glycinergic hyperpolarizing transition is not a necessary condition for the developmental refinement of inhibitory synaptic inputs.

Neurotransmitter Switch from GABA to Glycine is Undisturbed in KCC2-KD Mice

While MNTB terminals in mature animals release almost exclusively glycine (Finlayson and Caspary 1991; Moore and Caspary 1983; Sommer et al. 1993), MNTB terminals in neonatal animals predominantly release GABA (Hirtz et al. 2012; Kim and Kandler 2010; Kotak et al. 1998; Nabekura et al. 2004). The developmental mechanisms that govern this GABA-to-glycine transition are not well understood (Awatramani et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2001; Kotak et al. 1998). To investigate a possible role of the change in the polarity switch of GABA/glycinergic responses in the neurotransmitter switch, we investigated the kinetics and pharmacology of MNTB-elicited responses in the LSO of WT and KCC2-KD mice.

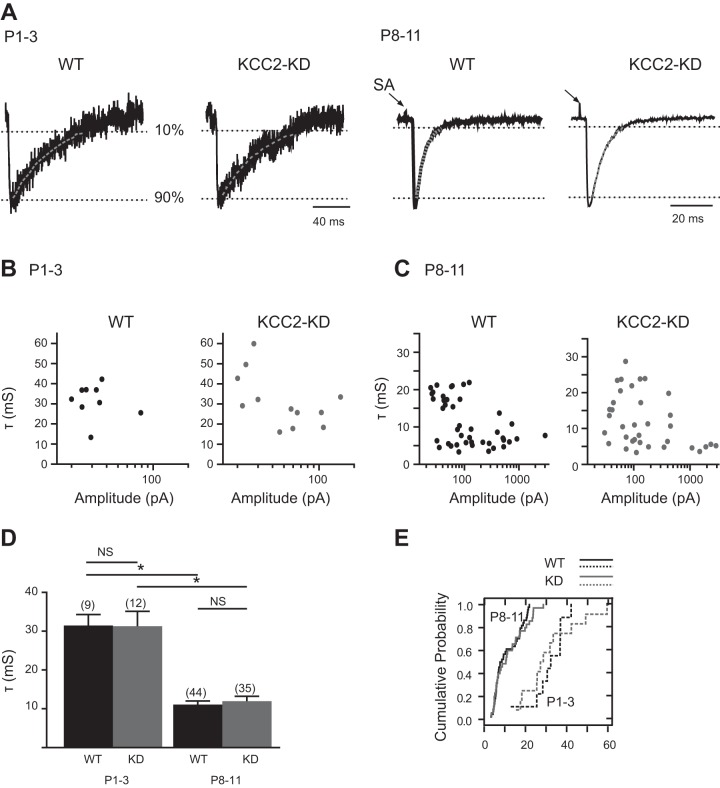

GABA- and glycine-mediated postsynaptic currents are distinguished by their decay times, with glycine-mediated currents exhibiting a faster decay than GABA-mediated responses (Nabekura et al. 2004; Russier et al. 2002). Accordingly, at MNTB-LSO synapses an increasing glycinergic component leads to a developmental decrease of the decay times of MNTB-elicited postsynaptic currents (Nabekura et al. 2004). To investigate whether developmental decline of GABA transmission at MNTB-LSO synapses is affected by the loss of the depolarization-to-hyperpolarization transition, we compared the decay kinetics of MNTB-elicited responses in WT and KCC2-KD mice at P1-3, when GABA predominates, and at P8-11, when glycine predominates (Kim and Kandler 2010; Nabekura et al. 2004). At P1-3, the decays of single-fiber responses were well fitted by single exponentials (Fig. 4A) and there was no difference between the decay times (τ) of single-fiber responses of WT (31.4 ± 2.8 ms; n = 9) and KCC2-KD (31.3 ± 3.8 ms; n = 12, P > 0.5, Mann-Whitney U-test) mice (Fig. 4, A and B). In WT mice at P8-11, the decay times of single-fiber responses were 11.07 ± 0.94 ms (n = 44) and not significantly different from KCC2-KD mice [11.97 ± 1.25 ms (n = 35); P > 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test]. In both WT and KCC2-KD mice, the τs decreased significantly from P1-3 to P8-11 (P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U-test; Fig. 4, D and E), which is consistent with a transition from GABAergic to glycinergic neurotransmission (Awatramani et al. 2005; Jonas et al. 1998; Nabekura et al. 2004).

Fig. 4.

Decay time constants (τ) of single-fiber MNTB-LSO inputs decrease to a similar degree in WT and KCC2-KD mice. A: representative example of decay time (τ) analysis from single-fiber MNTB-LSO inputs in P1-3 and P8-11 in WT (left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice. Dotted lines indicate 10% and 90% of peak amplitude. Stimulus artifacts are truncated. B: decay time constants of single-fiber responses as a function of their amplitudes in LSO neurons at P1-3 in WT (left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice. C: same as B but at P8-11. D: average τs of single-fiber responses at P1-3 (n = 9 for WT and n = 12 for KCC2-KD) and at P8-11 (n = 44 for WT and n = 35 for KCC2-KD). *P < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U-test). E: cumulative probability histograms for τs of single-fiber LSO responses at P1-3 (dashed line) and P8-11 (solid line) in WT and KCC2-KD mice. Cumulative probability distributions were analyzed with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

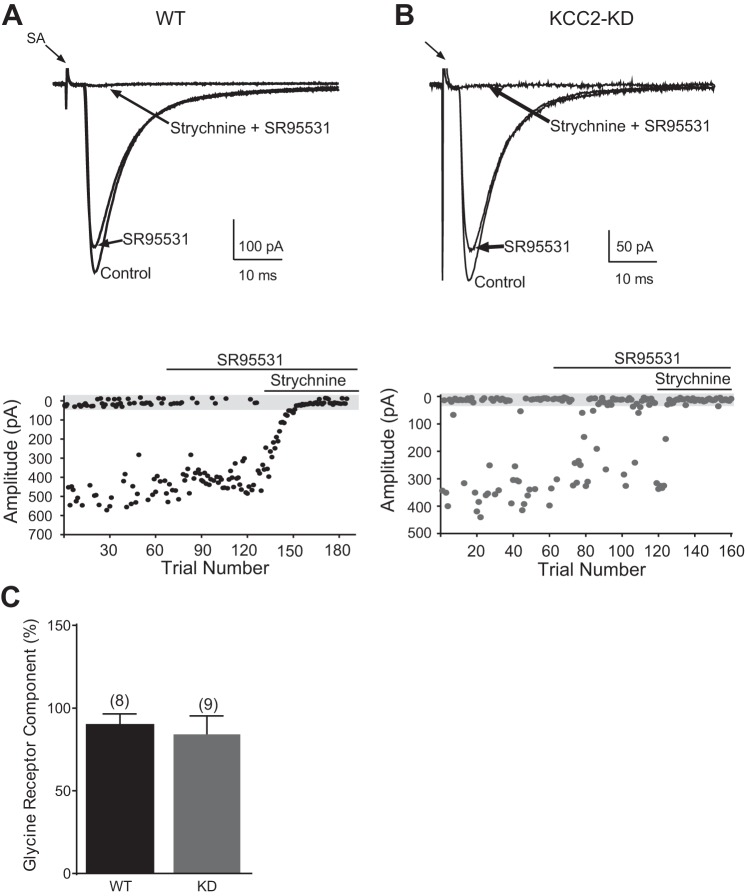

We next used the GABAAR antagonist SR95531 (10 μM) to measure the contribution of GABA transmission to single-fiber MNTB-LSO responses at P8-11, the age when MNTB-LSO synapses are primarily glycinergic (Kim and Kandler 2010; Kotak et al. 1998; Nabekura et al. 2004). In WT mice, SR95531 reduced the peak amplitude of single-fiber MNTB-LSO responses by ∼10% (to 90.0 ± 6.5%, n = 8) (Fig. 5C), indicating that MNTB synapses are predominantly glycinergic. In KCC2-KD mice the effects of SR95531 were not significantly different from those in WT mice, causing a reduction of the average peak amplitude to 84.1 ± 11.2% (n = 9, P > 0.05, Student's t-test). Taken together, our results from both the decay time analysis as well as pharmacology indicate that the excitatory-to-inhibitory transition of MNTB-LSO synapses is not necessary for the developmental transition from a GABA to glycinergic transmission.

Fig. 5.

Developmental shift from GABA to glycine transmission in the MNTB-LSO pathway is undisturbed in KCC2-KD mice. A and B, top: example traces of single-fiber LSO neuron responses before and after application of the GABAA receptor antagonist SR95531 (10 μM) and the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (1 μM) in WT (A) and KCC2-KD (B) mice at P8-11. Stimulus artifacts are truncated. Bottom: amplitudes of single-fiber responses for WT (A) and KCC2-KD (B) mice. Gray bar indicates amplitudes considered failures. C: average glycine receptor component in WT (n = 8) and KCC2-KD (n = 9) mice.

Loss of Depolarization-Hyperpolarization Transition Has No Effect on Maturation of Glutamatergic Inputs from Cochlear Nucleus

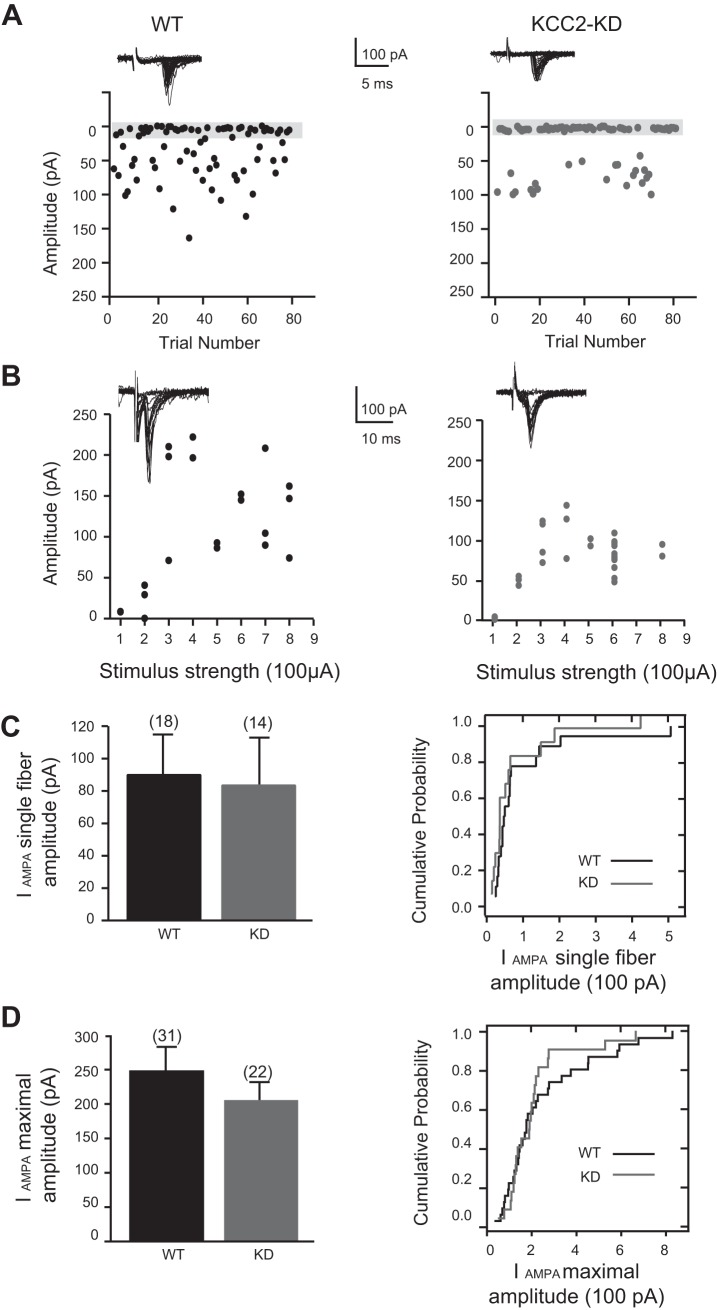

Because in KCC2-KD mice MNTB inputs remain depolarizing after P7, LSO neurons in KCC2-KD mice receive excitatory drive not only from the glutamatergic inputs from the ipsilateral CN but also from the MNTB. Therefore, we wondered whether LSO neurons engage homeostatic mechanisms (Maffei and Turrigiano 2008; Turrigiano 2012) and decrease the strength of glutamatergic CN inputs to adjust its net synaptic strength. To investigate this, we measured minimal and maximal response amplitudes elicited by stimulation of CN-LSO fibers in the ventral acoustic stria just lateral to the LSO. In these experiments, inhibitory responses were blocked by the GABAAR antagonist SR95531 (10 μM) or bicuculline (10 μM) and the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (1 μM). We first measured glutamatergic synaptic responses mediated by AMPARs by hyperpolarizing the membrane potential to −80 mV to prevent any significant activation of NMDARs. In P10-12 WT mice, the mean amplitude of single-fiber, AMPAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) was 89.2 ± 27.0 pA (n = 18) (Fig. 6, A–C) and those for maximal responses was 247.4 ± 35 pA (n = 31) (Fig. 6, B and D). In KCC2-KD mice, the amplitudes for both minimal and maximal responses were similar to those of WT animals [single-fiber responses: −81.9 ± 29.6 pA (n = 14), P > 0.1; maximal stimulation responses: 205.6 ± 30 pA (n = 22), P > 0.5] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Similar AMPA receptor-mediated CN-LSO responses in WT and KCC2-KD mice. A: representative example of single-fiber CN-LSO currents elicited by minimal stimulations at a holding potential of −80 mV in the presence of bicuculline (10 μM) and strychnine (1 μM). Insets: example traces from a LSO neuron in WT (left) and KCC2-KD (right) mice plotted as a function of stimulus trial number. Gray bar indicates failures. B: representative examples of stimulus-response relationship of the CN synaptic inputs onto a single LSO neuron. Experimental conditions as in A. Maximal amplitude values were derived from the average of at least 10 responses at stimulus strengths with plateaued amplitudes. C: average CN(AMPA) single-fiber current (IAMPA) amplitudes (left) and cumulative probability histograms of single-fiber amplitudes (right) of neurons from WT (n = 18) and KCC2-KD (n = 14) mice. D: average CN(AMPA) maximal fiber current amplitudes (left) and cumulative probability histograms of maximal fiber current amplitudes (right) for neurons from WT (n = 31) and KCC2-KD (n = 22) mice. For C and D, there was no significant difference between genotypes (unpaired Student's t-test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

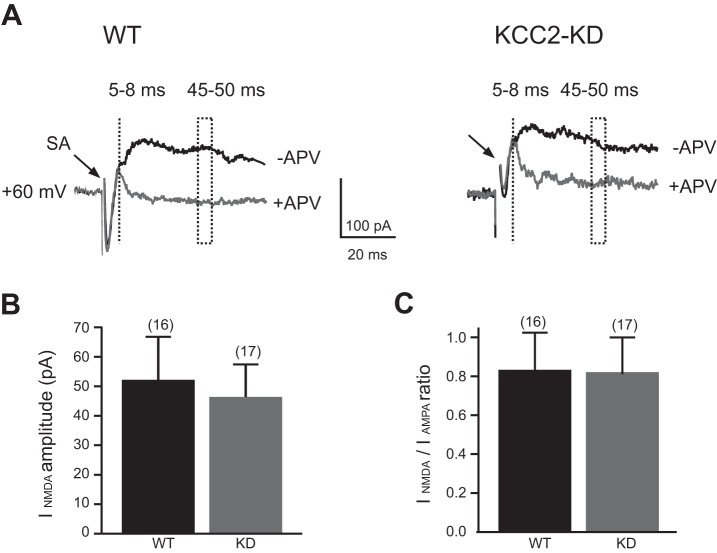

Glutamatergic CN-LSO synapses also activate NMDARs, with a gradual decrease in the NMDAR-mediated EPSC contribution during the first two postnatal weeks (Case et al. 2011; Ene et al. 2003). To test whether the maturation of NMDAR-mediated, ipsilaterally elicited postsynaptic responses was impaired in KCC2-KD, we recorded CN-LSO responses while clamping LSO neurons at +60 mV. At these conditions ipsilateral EPSCs were outwardly directed and exhibited a long decay time (Fig. 7). Application of the specific NMDAR antagonist APV (50 μM) abolished the late, long-lasting component without affecting the early AMPAR-mediated component of EPSCs. We measured the NMDAR-mediated synaptic component at a latency of 45 ms, a time point when responses were purely mediated by NMDARs. In WT mice, the mean amplitude of NMDAR currents (INMDA) was 52.2 ± 14.6 pA (n = 17) and was not significantly different from INMDA in KCC2-KD mice 46.4 ± 11.0 pA (n = 16) (Fig. 7B). Similarly, we found no difference in the ratio of INMDA to IAMPA input between WT [0.83 ± 0.19 (n = 17)] and KCC2-KD [0.81 ± 0.19 (n = 16); P > 0.5, Student's t-test] mice.

Fig. 7.

NMDA receptor-mediated CN-LSO responses were not different between WT and KCC2-KD mice at P9-12. A: representative traces of CN-LSO responses recorded at holding potential of +60 mV in the presence of bicuculline (10 μM) and strychnine (1 μM) in control conditions (−APV) and in the presence of APV (50 μM; +APV). At 45–50 ms after stimulus, responses were purely mediated by NMDA receptors. Stimulus artifacts are truncated. B: average maximal CN(NMDA) current (INMDA) amplitudes from neurons of WT (n = 16) and KCC2-KD (n = 17) mice. C: average CN(NMDA/AMPA) ratios for WT and KCC2-KD mice. There was no significant difference between genotypes (unpaired Student's t-test).

In summary, our results indicate that CN-LSO synapses develop normally in KCC2-KD mice, indicating that the continuous excitatory drive of MNTB inputs beyond P7 does not engage homeostatic mechanisms that would result in a decrease of glutamatergic CN-LSO connections.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of the developmental excitatory-inhibitory transition of GABA/glycinergic MNTB-LSO synapses in the maturation of inhibitory and excitatory synapses in the LSO. We found that in KCC2-KD mice, in which GABA and glycine remain excitatory beyond the second postnatal week, many key aspects of synaptic maturation in the LSO, such as the elimination and strengthening of MNTB-LSO connections, the transition to a predominantly glycinergic phenotype, and the maturation of glutamatergic CN-LSO inputs, proceed undisturbed. Our results indicate that the development and refinement of the LSO circuitry before hearing onset occurs independent of the hyperpolarizing action of GABA and glycine.

The mammalian KCC2 gene (Slc12a5) generates two splice variants, KCC2a and KCC2b, that differ in their NH2-terminus amino acids (Uvarov et al. 2007). The expression of both KCC2 isoforms is neuron specific, but their expression levels vary across different regions of the brain (Markkanen et al. 2014; Uvarov et al. 2007). Notably, while KCC2a is widely expressed in the brain stem, its expression is absent in auditory brain stem nuclei, including the superior olivary complex, which only expresses KCC2b. Consistent with this, we found that in KCC2-KD mice GABA and glycine continue to elicit an intracellular calcium increase in LSO neuron during the second postnatal week, instead of the decrease in [Ca2+]i of WT mice (Fig. 1) (Kullmann et al. 2002). Our results are consistent with previous electrophysiological recordings showing a positive shift of Eglycine in LSO neurons in these mice at P12 (Balakrishnan et al. 2003). Together these results provide further evidence that KCC2b is the major isoform mediating chloride outward transport in the LSO, and they indicate that the positive shift of ECl due to deletion of KCC2b is not rescued by an upregulation of KCC2a-mediated transport activity.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the depolarizing-to-hyperpolarizing transition of GABA and glycine plays an important role in the development of synaptic circuits. Elimination of GABAergic depolarizations by overexpression of KCC2 (Lee et al. 2005) or genetic deletion of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (Delpire et al. 1999), the main neuronal chloride inward transporter, demonstrated that GABA depolarizations regulate neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation (Reynolds et al. 2008; Young et al. 2012) and provide a stimulating signal for neuronal migration (Bortone and Polleux 2009). The latter effects appear to be specific for tangentially migrating interneurons, as elimination of GABAergic depolarizations had no effect on radially migrating excitatory neurons (Cancedda et al. 2007). At later stages of circuit maturation, GABA depolarizations regulate the number and strength of both GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses (Akerman and Cline 2006; Chudotvorova et al. 2005; Pfeffer et al. 2009; Wang and Kriegstein 2008) and promote dendritic growth (Cancedda et al. 2007). Because premature KCC2 expression results in an increase in the number of GABARs, GABA synapses, and GABAergic miniature events (Akerman and Cline 2006; Chudotvorova et al. 2005), a major effect of GABA depolarizations on inhibitory maturation seems to be to restrain or delay an increase in inhibition. This may explain the observations that in the developing MNTB-LSO pathway (Kim and Kandler 2003), as well as the neocortex (Daw et al. 2007), strengthening of inhibitory inputs correlates with their transition to eliciting postsynaptic hyperpolarization.

Because of the restraining effects of GABA depolarizations on the maturation of inhibitory synapses, we expected to find some impairments or a delay in the developmental strengthening of MNTB-LSO connection in KCC2-KD mice. This, however, was not the case, as the GABA/glycinergic synaptic strengthening of both single-fiber connections developed undisturbed in KCC2-KD mice (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). A similar observation was recently made in cerebellar granule cells in which KCC2 has been deleted, where the normal number of inhibitory synapses and frequency of spontaneous and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents are maintained (Seja et al. 2012). In addition, our results show that a lack of GABA hyperpolarizations also has no effect on the developmental elimination of GABA/glycinergic MNTB-LSO connection because MNTB-LSO convergence ratios decreased similarly in KCC2-KD and WT mice. Taken together, the results from the MNTB-LSO system and cerebellum, compared with other systems, indicate diversity in the developmental regulation of inhibitory synaptic strength across different synapse types.

In addition to regulating the development of inhibitory synapses, GABA depolarizations have also been implicated in influencing the maturation of glutamatergic synapses (Akerman and Cline 2006; Ben-Ari et al. 2007) by, for example, supporting the generation of network activity or cooperating with NMDARs (Ben-Ari et al. 2007; Pfeffer et al. 2009). However, less is known about the degree to which glutamatergic synapses are regulated by GABAergic or glycinergic hyperpolarizations. Although a number of studies have shown that pharmacologically blocking GABA and glycine receptors results in homeostatic scaling of glutamatergic inputs (Galante et al. 2000; Turrigiano et al. 1998), these studies generally did not differentiate between whether drugs blocked depolarizing or hyperpolarizing responses and the degree to which shunting contributed to the observed effects. A recent study, which used conditional KCC2-knockout mice, found that abolishing the hyperpolarizing shift of GABAergic synapses did not influence the number of inhibitory synapses or the frequency of spontaneous and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (Seja et al. 2012). In line with this result, we found that preventing the hyperpolarization shift in the LSO had no effect on the strength or the NMDA-to-AMPA ratio of CN-LSO connections (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). In KCC2-KD mice, glutamatergic transmission was indistinguishable from that in age-matched WT mice and very similar to that found in other mouse strains (Noh et al. 2010) and rats (Alamilla and Gillespie 2011; Case et al. 2011). Because LSO neurons in KCC2-KD mice receive continued excitation from CN as well as MNTB, the unchanged strength of glutamatergic synapses in the LSO of KCC2-KD mice indicates that LSO neurons do not express or engage homeostatic mechanisms to maintain a specific level of excitatory-inhibitory balance. This conclusion is supported by the fact that LSO neurons fail to regulate excitatory input strength when the depolarization-hyperpolarization shift of MNTB inhibitory inputs is severely impaired but their strengthening occurs normally (Noh et al. 2010). It is possible that balancing bilateral excitatory and inhibitory input strength, an important prerequisite for encoding interaural sound level differences, occurs after hearing onset, a possibility that we could not address because of the sharp increase in the lethality of KCC2-KD mice around hearing onset (Woo et al. 2002; Zhu et al. 2005).

Beyond its chloride transport activity, KCC2 also has a morphogenetic role in the formation and motility of dendritic spines by interacting with the actin cytoskeleton (Gauvain et al. 2011; Li et al. 2007; Llano et al. 2015). Deletion of KCC2 results in longer, less mature, and more mobile spines, a decrease in glutamatergic synapses, and a reduced postsynaptic aggregation of GluR1-containing AMPARs. This morphogenetic role of KCC2 has been described on the level of spines, which contain the highest level of dendritic KCC2 (Gulyás et al. 2001). The fact that LSO neurons do not form spines may explain why the development of glutamatergic inputs to LSO neurons remains unaffected in KCC2-KD mice. It is possible that in the LSO, and perhaps other spineless neurons, KCC2's integrations with the cytoskeleton regulate overall dendritic growth (Kandler and Friauf 1995b; Rietzel and Friauf 1998; Sanes et al. 1992), providing a possible explanation for the early expression of KCC2 protein in the LSO many days before these proteins form functioning chloride transporters (Balakrishnan et al. 2003; Blaesse et al. 2006).

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC-011499 (K. Kandler), Grant 132RA03 (E. Bach), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-036758 (E. Delpire).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: H.L., E.D., and K.K. conception and design of research; H.L., E.B., J.N., and E.D. performed experiments; H.L., E.B., and J.N. analyzed data; H.L., E.B., J.N., and K.K. interpreted results of experiments; H.L., E.B., and J.N. prepared figures; H.L., E.B., J.N., and K.K. drafted manuscript; H.L., E.B., E.D., and K.K. approved final version of manuscript; E.B. and K.K. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. A. Garver and X. Gu for technical support.

Present address of H. Lee: Departments of Biology and Neurobiology and Bio-X, James H. Clark Center, 318 Campus Dr., Stanford, CA 94305.

REFERENCES

- Akerman CJ, Cline HT. Depolarizing GABAergic conductances regulate the balance of excitation to inhibition in the developing retinotectal circuit in vivo. J Neurosci 26: 5117–5130, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamilla J, Gillespie DC. Glutamatergic inputs and glutamate-releasing immature inhibitory inputs activate a shared postsynaptic receptor population in lateral superior olive. Neuroscience 196: 285–296, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamilla J, Gillespie DC. Maturation of calcium-dependent GABA, glycine, and glutamate release in the glycinergic MNTB-LSO pathway. PLoS One 8: e75688, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani GB, Turecek R, Trussell LO. Staggered development of GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the MNTB. J Neurophysiol 93: 819–828, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan V, Becker M, Lohrke S, Nothwang HG, Guresir E, Friauf E. Expression and function of chloride transporters during development of inhibitory neurotransmission in the auditory brainstem. J Neurosci 23: 4134–4145, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Nothwang HG, Friauf E. Differential expression pattern of chloride transporters NCC, NKCC2, KCC1, KCC3, KCC4, and AE3 in the developing rat auditory brainstem. Cell Tissue Res 312: 155–165, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. The GABA excitatory/inhibitory developmental sequence: a personal journey. Neuroscience 279: 187–219, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev 87: 1215–1284, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaesse P, Guillemin I, Schindler J, Schweizer M, Delpire E, Khiroug L, Friauf E, Nothwang HG. Oligomerization of KCC2 correlates with development of inhibitory neurotransmission. J Neurosci 26: 10407–10419, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone D, Polleux F. KCC2 expression promotes the termination of cortical interneuron migration in a voltage-sensitive calcium-dependent manner. Neuron 62: 53–71, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K, Poo MM. Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J Neurosci 27: 5224–5235, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DT, Zhao X, Gillespie DC. Functional refinement in the projection from ventral cochlear nucleus to lateral superior olive precedes hearing onset in rat. PLoS One 6: e20756, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini E, Gaiarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci 14: 515–519, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudotvorova I, Ivanov A, Rama S, Hubner CA, Pellegrino C, Ben-Ari Y, Medina I. Early expression of KCC2 in rat hippocampal cultures augments expression of functional GABA synapses. J Physiol 566: 671–679, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clause A, Kim G, Sonntag M, Weisz CJ, Vetter DE, Rubsamen R, Kandler K. The precise temporal pattern of prehearing spontaneous activity is necessary for tonotopic map refinement. Neuron 82: 822–835, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Ashby MC, Isaac JT. Coordinated developmental recruitment of latent fast spiking interneurons in layer IV barrel cortex. Nat Neurosci 10: 453–461, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Lu J, England R, Dull C, Thorne T. Deafness and imbalance associated with inactivation of the secretory Na-K-2Cl co-transporter. Nat Genet 22: 192–195, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Lohrke S, Friauf E. Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action in rat auditory neurones is due to age-dependent Cl− regulation. J Physiol 520: 121–137, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ene FA, Kalmbach A, Kandler K. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the lateral superior olive activate TRP-like channels: age- and experience-dependent regulation. J Neurophysiol 97: 3365–3375, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ene FA, Kullmann PH, Gillespie DC, Kandler K. Glutamatergic calcium responses in the developing lateral superior olive: receptor types and their specific activation by synaptic activity patterns. J Neurophysiol 90: 2581–2591, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson PG, Caspary DM. Low-frequency neurons in the lateral superior olive exhibit phase-sensitive binaural inhibition. J Neurophysiol 65: 598–605, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friauf E, Rust MB, Schulenborg T, Hirtz JJ. Chloride cotransporters, chloride homeostasis, and synaptic inhibition in the developing auditory system. Hear Res 279: 96–110, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galante M, Nistri A, Ballerini L. Opposite changes in synaptic activity of organotypic rat spinal cord cultures after chronic block of AMPA/kainate or glycine and GABAA receptors. J Physiol 523: 639–651, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, Stricker C, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Transition from GABAergic to glycinergic synaptic transmission in newly formed spinal networks. J Neurophysiol 86: 492–502, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvain G, Chamma I, Chevy Q, Cabezas C, Irinopoulou T, Bodrug N, Carnaud M, Lévi S, Poncer JC. The neuronal K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 influences postsynaptic AMPA receptor content and lateral diffusion in dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 15474–15479, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming GL, Song H. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature 439: 589–593, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie DC, Kim G, Kandler K. Inhibitory synapses in the developing auditory system are glutamatergic. Nat Neurosci 8: 332–338, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás AI, Sík A, Payne JA, Kaila K, Freund TF. The KCl cotransporter, KCC2, is highly expressed in the vicinity of excitatory synapses in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 13: 2205–2217, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz JJ, Braun N, Griesemer D, Hannes C, Janz K, Lohrke S, Muller B, Friauf E. Synaptic refinement of an inhibitory topographic map in the auditory brainstem requires functional Cav1.3 calcium channels. J Neurosci 32: 14602–14616, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Sandkuhler J. Corelease of two fast neurotransmitters at a central synapse. Science 281: 419–424, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Price TJ, Payne JA, Puskarjov M, Voipio J. Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 15: 637–654, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakazu Y, Akaike N, Komiyama S, Nabekura J. Regulation of intracellular chloride by cotransporters in developing lateral superior olive neurons. J Neurosci 19: 2843–2851, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Clause A, Noh J. Tonotopic reorganization of developing auditory brainstem circuits. Nat Neurosci 12: 711–717, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E. Development of glycinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the auditory brainstem of perinatal rats. J Neurosci 15: 6890–6904, 1995a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E. Development of electrical membrane properties and discharge characteristics of superior olivary complex neurons in fetal and postnatal rats. Eur J Neurosci 7: 1773–1790, 1995b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasyanov AM, Safiulina VF, Voronin LL, Cherubini E. GABA-mediated giant depolarizing potentials as coincidence detectors for enhancing synaptic efficacy in the developing hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 3967–3972, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Kandler K. Elimination and strengthening of glycinergic/GABAergic connections during tonotopic map formation. Nat Neurosci 6: 282–290, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Kandler K. Synaptic changes underlying the strengthening of GABA/glycinergic connections in the developing lateral superior olive. Neuroscience 171: 924–933, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak VC, Korada S, Schwartz IR, Sanes DH. A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system. J Neurosci 18: 4646–4655, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann PH, Ene FA, Kandler K. Glycinergic and GABAergic calcium responses in the developing lateral superior olive. Eur J Neurosci 15: 1093–1104, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann PH, Kandler K. Glycinergic/GABAergic synapses in the lateral superior olive are excitatory in neonatal C57Bl/6J mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 131: 143–147, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Chen CX, Liu YJ, Aizenman E, Kandler K. KCC2 expression in immature rat cortical neurons is sufficient to switch the polarity of GABA responses. Eur J Neurosci 21: 2593–2599, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Khirug S, Cai C, Ludwig A, Blaesse P, Kolikova J, Afzalov R, Coleman SK, Lauri S, Airaksinen MS, Keinänen K, Khiroug L, Saarma M, Kaila K, Rivera C. KCC2 interacts with the dendritic cytoskeleton to promote spine development. Neuron 56: 1019–1033, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano O, Smirnov S, Soni S, Golubtsov A, Guillemin I, Hotulainen P, Medina I, Nothwang HG, Rivera C, Ludwig A. KCC2 regulates actin dynamics in dendritic spines via interaction with β-PIX. J Cell Biol 209: 671–686, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei A, Turrigiano G. The age of plasticity: developmental regulation of synaptic plasticity in neocortical microcircuits. Prog Brain Res 169: 211–223, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Avery RB, Christie BR, Johnston D. Dihydropyridine-sensitive, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels contribute to the resting intracellular Ca2+ concentration of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 76: 3460–3470, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markkanen M, Karhunen T, Llano O, Ludwig A, Rivera C, Uvarov P, Airaksinen MS. Distribution of neuronal KCC2a and KCC2b isoforms in mouse CNS. J Comp Neurol 522: 1897–1914, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Caspary DM. Strychnine blocks binaural inhibition in lateral superior olivary neurons. J Neurosci 3: 237–242, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabekura J, Katsurabayashi S, Kakazu Y, Shibata S, Matsubara A, Jinno S, Mizoguchi Y, Sasaki A, Ishibashi H. Developmental switch from GABA to glycine release in single central synaptic terminals. Nat Neurosci 7: 17–23, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh J, Seal RP, Garver JA, Edwards RH, Kandler K. Glutamate co-release at GABA/glycinergic synapses is crucial for the refinement of an inhibitory map. Nat Neurosci 13: 232–238, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata K, Oide M, Tanaka H. Excitatory and inhibitory actions of GABA and glycine on embryonic chick spinal neurons in culture. Brain Res 144: 179–184, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Developmental neurotransmitters? Neuron 36: 989–991, 2002a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 715–727, 2002b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CK, Stein V, Keating DJ, Maier H, Rinke I, Rudhard Y, Hentschke M, Rune GM, Jentsch TJ, Hubner CA. NKCC1-dependent GABAergic excitation drives synaptic network maturation during early hippocampal development. J Neurosci 29: 3419–3430, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, Brustein E, Liao M, Mercado A, Babilonia E, Mount DB, Drapeau P. Neurogenic role of the depolarizing chloride gradient revealed by global overexpression of KCC2 from the onset of development. J Neurosci 28: 1588–1597, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietzel H, Friauf E. Neuron types in the rat lateral superior olive and developmental changes in the complexity of their dendritic arbors. J Comp Neurol 390: 20–40, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russier M, Kopysova IL, Ankri N, Ferrand N, Debanne D. GABA and glycine co-release optimizes functional inhibition in rat brainstem motoneurons in vitro. J Physiol 541: 123–137, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes DH, Friauf E. Development and influence of inhibition in the lateral superior olivary nucleus. Hear Res 147: 46–58, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes DH, Song J, Tyson J. Refinement of dendritic arbors along the tonotopic axis of the gerbil lateral superior olive. Dev Brain Res 67: 47–55, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seja P, Schonewille M, Spitzmaul G, Badura A, Klein I, Rudhard Y, Wisden W, Hubner CA, De Zeeuw CI, Jentsch TJ. Raising cytosolic Cl− in cerebellar granule cells affects their excitability and vestibulo-ocular learning. EMBO J 31: 1217–1230, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Kakazu Y, Okabe A, Fukuda A, Nabekura J. Experience-dependent changes in intracellular Cl− regulation in developing auditory neurons. Neurosci Res 48: 211–220, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer I, Lingenhohl K, Friauf E. Principal cells of the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: an intracellular in vivo study of their physiology and morphology. Exp Brain Res 95: 223–239, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, McGee J, Walsh EJ. Frequency- and level-dependent changes in auditory brainstem responses (ABRS) in developing mice. J Acoust Soc Am 119: 2242–2257, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titz S, Hans M, Kelsch W, Lewen A, Swandulla D, Misgeld U. Hyperpolarizing inhibition develops without trophic support by GABA in cultured rat midbrain neurons. J Physiol 550: 719–730, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollin DJ. The lateral superior olive: a functional role in sound source localization. Neuroscientist 9: 127–143, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozuka Y, Fukuda S, Namba T, Seki T, Hisatsune T. GABAergic excitation promotes neuronal differentiation in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuron 47: 803–815, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: local and global mechanisms for stabilizing neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a005736, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature 391: 892–896, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvarov P, Ludwig A, Markkanen M, Pruunsild P, Kaila K, Delpire E, Timmusk T, Rivera C, Airaksinen MS. A novel N-terminal isoform of the neuron-specific K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. J Biol Chem 282: 30570–30576, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcher J, Hassfurth B, Grothe B, Koch U. Comparative posthearing development of inhibitory inputs to the lateral superior olive in gerbils and mice. J Neurophysiol 106: 1443–1453, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. GABA regulates excitatory synapse formation in the neocortex via NMDA receptor activation. J Neurosci 28: 5547–5558, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Defining the role of GABA in cortical development. J Physiol 587: 1873–1879, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo NS, Lu J, England R, McClellan R, Dufour S, Mount DB, Deutch AY, Lovinger DM, Delpire E. Hyperexcitability and epilepsy associated with disruption of the mouse neuronal-specific K-Cl cotransporter gene. Hippocampus 12: 258–268, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SZ, Taylor MM, Wu S, Ikeda-Matsuo Y, Kubera C, Bordey A. NKCC1 knockdown decreases neuron production through GABAA-regulated neural progenitor proliferation and delays dendrite development. J Neurosci 32: 13630–13638, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Lovinger D, Delpire E. Cortical neurons lacking KCC2 expression show impaired regulation of intracellular chloride. J Neurophysiol 93: 1557–1568, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]