Abstract

In Gram-negative bacteria, the active efflux is an important mechanism of antimicrobial resistance, but little is known about the Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC). It is mediated primarily by pumps belonging to the RND (resistance-nodulation-cell division) family, and only AcrB, part of the AcrAB-TolC tripartite system, was characterized in ECC. However, detailed genome sequence analysis of the strain E. cloacae subsp. cloacae ATCC 13047 revealed to us that 10 other genes putatively coded for RND-type transporters. We then characterized the role of all of these candidates by construction of corresponding deletion mutants, which were tested for their antimicrobial susceptibility to 36 compounds, their virulence in the invertebrate Galleria mellonella model of infection, and their ability to form biofilm. Only the ΔacrB mutant displayed significantly different phenotypes compared to that of the wild-type strain: 4- to 32-fold decrease of MICs of several antibiotics, antiseptics, and dyes, increased production of biofilm, and attenuated virulence in G. mellonella. In order to identify specific substrates of each pump, we individually expressed in trans all operons containing an RND pump-encoding gene into the ΔacrB hypersusceptible strain. We showed that three other RND-type efflux systems (ECL_00053-00055, ECL_01758-01759, and ECL_02124-02125) were able to partially restore the wild-type phenotype and to superadd to and even enlarge the broad range of antimicrobial resistance. This is the first global study assessing the role of all RND efflux pumps chromosomally encoded by the ECC, which confirms the major role of AcrB in both pathogenicity and resistance and the potential involvement of other RND-type members in acquired resistance.

INTRODUCTION

The efflux systems are important mechanisms of drug resistance in bacteria. Five major groups of drug efflux transporter families have been identified so far: the RND (resistance-nodulation-cell division), MFS (major facilitator superfamily), MATE (multidrug and toxic compound extrusion), and ABC (ATP-binding cassette) families (1, 2). Those belonging to the RND family play a major role in resistance of Gram-negative bacteria to a wide range of toxic compounds, including antibiotics, biocides, and heavy metals (3, 4). These efflux systems consist of three components: the inner membrane protein (IMP), the periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP), and the outer membrane protein (OMP). The electrochemical potential of H+ across cell membranes appears to be the driving force for drug efflux by RND family transporters (5, 6). The AcrAB-TolC tripartite efflux system is the most important one in Gram-negative bacteria, being involved in both intrinsic and acquired resistance to antibiotics, detergents, biocides, dyes, free fatty acids, and even solvents by constitutive expression and overexpression of the acrAB-tolC operon (1, 4, 7–9). In addition, acrB mutants in Enterobacteriaceae, selected in vivo and in vitro, are more susceptible to many antimicrobials (10, 11). The role of RND efflux pumps is not limited to the multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype, since some of them have been shown to be required for virulence traits of different Gram-negative pathogens (11, 12). This explains why AcrB is considered the main clinically relevant RND system and constitutes a privileged target for the development of efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) molecules that could be used to treat infections (13–15). In Enterobacteriaceae, numerous other genes encoding RND pumps are present in the genomes, but their roles have been poorly investigated so far.

Species of the Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC) are widely encountered in nature and also are part of the intestinal microbiota of both humans and animals (16). E. cloacae has taken on clinical importance during the last decade and has emerged as a redoubtable pathogen, accounting for up to 5% of hospital-acquired bacteremia, 5% of nosocomial pneumonia, 4% of nosocomial urinary tract infections, and 10% of postsurgical peritonitis cases (17, 18). ECC species are well adapted to the hospital environment and are able to develop MDR with very few therapeutic options. All ECC strains naturally possess the cephalosporinase-encoding ampC gene, the expression of which can be induced by some β-lactams, and it is responsible for the intrinsic resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and first- and second-generation cephalosporins (19). The second chromosomal mechanism implicated in antimicrobial resistance in ECC is associated with the presence of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system (20).

Using the available genome sequence of E. cloacae subsp. cloacae ATCC 13047, we identified 10 genes coding for putative RND efflux pumps homologous to AcrB (21). The aim of this study was to characterize the 11 RND-type efflux systems by constructing the corresponding mutants and by performing trans-complementations using the acrB mutant strain. In addition to confirming the important role of AcrB in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence, we showed that other RND pumps also may have a role in MDR traits of this opportunistic pathogen.

(These results were presented in part at the 55th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Diego, CA, 17 to 21 September 2015 [22].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The reference strain used was E. cloacae subsp. cloacae ATCC 13047 (ECL13047), the genome sequence of which is available already (GenBank accession numbers CP002886, FP929040, and AGSY00000000) (21). Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae strains were cultured with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C in LB medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype/relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. cloacae subsp. cloacae strains | ||

| ECL13047 | ATCC 13047 | 21 |

| ΔacrB | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of acrB (ECL_01233) | This study |

| Δ00054 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_00054 | This study |

| Δ01758 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_01758 | This study |

| Δ01963 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_01963 | This study |

| Δ02125 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_02125 | This study |

| Δ02244 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_02244 | This study |

| Δ03149 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_03149 | This study |

| Δ03403 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_03403 | This study |

| Δ03767 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_03767 | This study |

| Δ04650 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_04650 | This study |

| Δ04888 | ECL13047 derivative with deletion of ECL_04888 | This study |

| ΔacrB/Δ00054 | ΔacrB derivative with deletion of ECL_00054 | This study |

| ΔacrB/Δ01758 | ΔacrB derivative with deletion of ECL_01758 | This study |

| ΔacrB/Δ02125 | ΔacrB derivative with deletion of ECL_02125 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_00053-55 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_01233-1234 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_01233-1234 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_01758 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_01758 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_01960-63 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_01960-63 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_02124-25 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_02124-25 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_02243-44 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_02243-44 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_03149-50 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_03149-50 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_03401-04 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_03401-03 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_03767 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_03767 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_04649-50 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_04649-50 | This study |

| ΔacrB/ECL_04888-93 | ECLΔacrB trans-complemented strain carrying pBAD202/D-TOPOΩECL_04888-93 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD202/D-TOPO | General expression vector with arabinose-inducible promoter, Kanr | Life Technologies |

| pKOBEG | Recombination vector, phage λ recγβα operon under the control of the pBAD promoter, Cmr | 23 |

| pKD4 | Plasmid containing an FRT-flanked kanamycin cassette, Kanr | 24 |

| pCP20_Gm | FLP-mediated recombination vector, Genr | 25 |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Genr, gentamicin resistant.

Construction of the knockout mutants.

The disruption of the genes encoding putative RND transporters was performed using the method previously described, with some modifications, using the Red helper plasmid pKOBEG (23, 24). This vector is a low-copy-number plasmid that contains a gene for chloramphenicol resistance selection, a temperature-sensitive origin of replication, and a gene encoding a recombinase. Briefly, pKOBEG first was introduced into the competent cells of ECL13047 by electroporation, and transformants were selected on LB agar with chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml) after incubation for 24 h at 30°C. A selectable kanamycin resistance cassette (flanked by flippase recognition target [FRT] sequences) was amplified by PCR using DNA of pKD4 plasmid as the template. The primers used included 5′ extensions with homology for the candidate genes (around 50 bases) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR product was introduced into the ECL13047/pKOBEG plasmid by electroporation, and after homologous recombination, the disruption of the candidate gene was obtained. Selected clones were cured for the pKOBEG plasmid following a heat shock, creating the kanamycin-resistant variant. In order to have deletion mutants free of the antibiotic marker, strains then were transformed with the pCP20_Gm plasmid, which is able to express the FLP nuclease that recognizes the FRT sequences present on either side of the kan gene (25). Lastly, the mutants were verified by sequencing.

Construction of multicopy plasmid library containing putative RND transporter open reading frames (ORFs).

The ECC RND efflux pump-encoding genes or operons and their promoters were amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Each amplicon was TA cloned into the overexpression plasmid, pBAD202 directional TOPO (Invitrogen, Courtaboeuf, France). E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) carrying pBAD202 recombinants containing correctly oriented inserts were selected on LB plates with 40 mg/liter kanamycin. After purification, each plasmid carrying an operon containing an RND efflux pump-coding gene was used to transform acrB mutant cells of ECL13047 (ΔacrB strain) (Table 1).

RNA manipulations.

Total RNA was extracted from ΔacrB, ΔacrB/ECL_01233-34, ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55, ΔacrB/ECL_01758, and ΔacrB/ECL_02124-25 strains using the Direct-Zol RNA mini-prep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), and chromosomal DNA was removed by treating samples with the Turbo DNA-free kit (Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). RNA samples were quantified using the Biospec-Nano spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Noisiel, France), and the integrities were assessed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) experiments, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (∼1 μg) using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transcript levels of the efflux pump-encoding genes were determined by the ΔΔCT method (where CT is threshold cycle) using the rpoB gene as a housekeeping control gene as previously described (19).

Drug susceptibility testing.

MICs of different antibiotics, antiseptics, and biocides were determined by the microdilution method in Mueller-Hinton broth for all strains in three independent experiments (wild-type ECL13047, knockout deletion mutants, and trans-complemented ECLΔacrB strains). The tested molecules were antibiotics (β-lactams [piperacillin, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefepime, imipenem, and ertapenem], aminoglycosides [gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin], fluoroquinolones [norfloxacin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and moxifloxacin], tetracyclines [tetracycline and tigecycline], chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, fusidic acid, nitrofurantoin, and colistin), antiseptics (benzalkonium chloride, cetylpyridinium bromide, chlorhexidine, tetraphenylphosphonium chloride), heavy metals (copper [CuSO4], zinc [ZnSO4], manganese [MnSO4], mercury [HgCl2], and silver [AgNO3]), dyes (rhodamine 6G, acriflavine, acridine orange, crystal violet, ethidium bromide), sodium dodecyl-sulfate (SDS), and cathepsin E.

The MICs of levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol were determined for the wild-type, ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55, ΔacrB/ECL_01758, and ΔacrB/ECL_02124-25 strains with the efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at final concentrations of 10, 25, and 50 μg/ml.

In vitro phenotypic assays.

For the H2O2 challenge, wild-type and mutant cells (log-phase cultures) were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 by centrifugation and resuspended in distilled water with 20 mM H2O2. These cultures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Before and after the challenge, samples were taken for plate counting. The number of CFU was determined after 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h of incubation at 37°C. Survival was determined as the ratio of the number of CFU after treatment to the number of CFU at the zero time point.

The capacity of each mutant to form biofilm was evaluated at 24 h, 48 h, and one week. Briefly, they were incubated in polystyrene 96-well microplates with LB medium and at 37°C. At the selected time point, the formed biofilm was colored with crystal violet (1%) and each well was scanned at 580 nm. Each value was the means from at least three experiments, and a statistical comparison of means was performed by using Student's test.

Virulence in Galleria mellonella model.

The virulence of E. cloacae strains was tested in the G. mellonella model of infection. To this end, 10 μl of a suspension corresponding to an OD600 of 0.5 (i.e., 4.0 × 108 ± 1.0 × 108 CFU/ml) was injected dorsolaterally into the hemocoel of 20 larvae. After injection, the larvae were incubated at 37°C, and survival of the larvae was evaluated until 72 h postinfection. Each experiment was performed at least three times, and statistical comparisons were performed by using Student's test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of RND-type drug transporter ORFs.

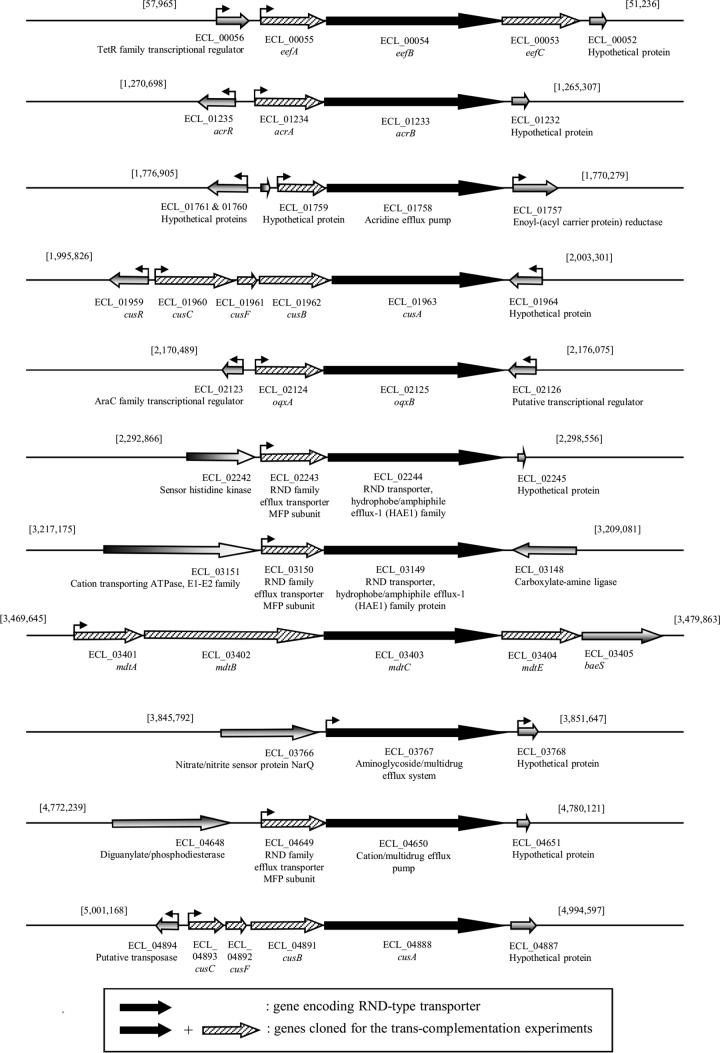

AcrAB-TolC is a well-characterized multidrug efflux pump of the RND family in E. cloacae (20, 26, 27). Based on the sequence of the protein AcrB (designated ECL_01233 in ECL13047), the inner membrane transporter protein of the system, we searched for the presence of other members of this family of transporters. BLAST analysis allowed the identification of 10 additional loci on the chromosomal DNA of E. cloacae ECL13047 (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Sequence similarities to AcrB varied from 41% to 89%, while amino acid identities were between 23% and 80% (Table 2). To date, two transporters of a tripartite MDR efflux system have been identified (AcrB and EefB [ECL_00054]) in the genome of the ATCC reference strain (20, 28), whereas two others were annotated as belonging to the RND family (ECL_02125 and ECL_02244) (21). ClustalW alignments of all RND-type transporters revealed that three of the five residues corresponding to the amino acids essential for the proton transport within the AcrB identified in E. coli (D407, R970, and T977) were present in all sequences (29, 30). For the other two residues, K939 was lacking in ECL_02444, ECL_01963, and ECL_04888 strains, and D408 was not present in ECL_0196 and ECL_04888 sequences (data not shown). Note that these three sequences were those showing the weakest percent identity to the AcrB sequence (23 to 25%). Except for ECL_03767, the corresponding genes appeared to be included into operon structures whose promoter regions were determined in silico (Fig. 1). We also looked at the presence of the G288 residue in amino acid sequences of the different transporters. Indeed, it has been shown recently in Salmonella that a G288D substitution in AcrB altered its substrate specificity, conferring at the same time decreased susceptibility to CIP or TET and increased susceptibility to doxorubicin and minocycline (31). Among inner membrane RND antiporters identified in E. cloacae, only ECL_1758, ECL_3149, and ECL_3403 did not present such residues that may, at least in part, explain that these pumps could have different substrates (see below).

TABLE 2.

List of the RND transporters identified in the genome of E. cloacae ATCC 13047 based on homology with the sequence of AcrB

| RND efflux gene | Gene name | Annotation | Size (bp/aa)a | % identity with acrB ECC | % positive for acrB ECC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECL_00054 | eefB | Multidrug efflux transport protein | 3,111/1,036 | 58 | 75 |

| ECL_01233 | acrB | AcrB protein | 3,147/1,048 | 100 | 100 |

| ECL_01758 | Acridine efflux pump | 3,096/1,031 | 49 | 68 | |

| ECL_01963 | cusA | Cu(I)/Ag(I) efflux system membrane protein | 3,009/1,002 | 23 | 41 |

| ECL_02125 | oqxB | RND family multidrug efflux permease | 3,153/1,050 | 41 | 62 |

| ECL_02244 | RND transporter, hydrophobe/amphiphile efflux-1 (HAE1) family | 3,075/1,024 | 25 | 44 | |

| ECL_03149 | Hydrophobe/amphiphile efflux-1 (HAE1) family protein | 3,135/1,044 | 40 | 59 | |

| ECL_03403 | mdtC | Multidrug efflux system subunit MdtC | 3,078/1,025 | 29 | 50 |

| ECL_03767 | Aminoglycoside/multidrug efflux system | 3,114/1,037 | 65 | 79 | |

| ECL_04650 | Cation/multidrug efflux pump | 3,114/1,037 | 80 | 89 | |

| ECL_04888 | cusA | Cu(I)/Ag(I) efflux system membrane protein | 3,147/1,048 | 24 | 43 |

bp, base pair; aa, amino acid.

FIG 1.

Genetic organization of the operons containing one gene coding for a putative RND efflux pump transporter homologous to AcrB.

Phenotypic analysis of the RND drug transporter mutants.

In order to characterize the role of the RND efflux pumps in E. cloacae, our first strategy was to construct individual deletion mutants of genes coding for the inner membrane proteins of the systems (that determine the substrate specificity of the efflux) and test them for their susceptibility to toxic compounds (antibiotics, antiseptics, biocides, heavy metals, and SDS), for their virulence, and for their ability to cope with different stresses. As expected, we showed that the acrB mutant was significantly more susceptible to several agents, such as antibiotics (such as fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, fusidic acid, and erythromycin), antiseptics (benzalkonium chloride and tetraphenylphosphonium chloride), dyes (rhodamine 6G, acriflavine, acridine orange, crystal violet, and ethidium bromide), and SDS (Table 3). It is worth noting that no differences in MICs were observed for β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and colistin. These results are in accordance with previous reports pointing out the importance of AcrB (and its overexpression) in antimicrobial resistance in E. cloacae (4, 27). Our data obtained with the other 10 mutants revealed that none of them showed an alteration in MICs of antimicrobial molecules tested (fold change of ≤4), likely because of the compensatory effect of AcrAB-TolC (data not shown). This confirmed that AcrAB-TolC is the unique RND-type efflux system involved in intrinsic resistance to toxic compounds (including antibiotics) in E. cloacae. Whatever the strain, we did not observe any modification in susceptibility to heavy metals, even for the two cusA mutant strains (ECL_01963 and ECL_04888), both encoding Cu(I)/Ag(I) efflux systems.

TABLE 3.

MICs of antibiotics, biocides, and metals for ECL13047 (wild type), ΔacrB, and ΔacrB transcomplemented strains carrying plasmids containing the different putative RND drug transporter ORFs

| Compounda | MIC (μg/ml) for strainb: |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECL13047 | ΔacrB | ΔacrB/ECL_01233-1234 | ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55 | ΔacrB/ECL_01758 | ΔacrB/ECL_01960-63 | ΔacrB/ECL_02124-25 | ΔacrB/ECL_02243-44 | ΔacrB/ECL_03149-50 | ΔacrB/ECL_03401-04 | ΔacrB/ECL_03767 | ΔacrB/ECL_04649-50 | ΔacrB/ECL_04888-93 | |

| Antibiotics | |||||||||||||

| Piperacillin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cefotaxime | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cefoxitin | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| Cefepime | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ertapenem | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| Gentamicin | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0,125 | 0.25 | 1 (4) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Tobramycin | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0,125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0,25 | 0.25 |

| Amikacin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 (4) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Norfloxacin | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.125 (4) | 0.125 (4) | 0.125 (4) | 0.032 | 0.5 (16) | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.064 | 0.016 | 0.064 (4) | 0.25 (16) | 0.125 (8) | 0.016 | 0.25 (16) | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.032 (4) | 0.064 (8) | 0.064 (8) | 0.016 | 0.125 (16) | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.064 | 0.008 | 0.125 (16) | 0.125 (16) | 0.25 (32) | 0.008 | 0.125 (16) | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| Tetracycline | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 (4) | 1 (8) | 2 (16) | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| SXT | 2 | 0.5 | 2 (4) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 32 (64) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 0.5 | 4 (8) | 8 (16) | 2 (4) | 1 | 32 (64) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fusidic acid | 256 | 4 | 256 (64) | 256 (64) | 64 (16) | 4 | 16 (4) | 4 | 8 | 32 (8) | 64 (16) | 4 | 4 |

| Nitrofuratoin | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 32 |

| Erythromycin | 256 | 16 | 256 (16) | 256 (16) | 256 (16) | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 64 (4) | 16 |

| Colistin | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Antiseptics | |||||||||||||

| Benzalkonium chloride | 32 | 4 | 32 (8) | 16 (4) | 8 | 8 | 16 (4) | 8 | 16 (4) | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| CTAB | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Chlorhexidine | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 (4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tetraphenylphosphosnium | >1,024 | 128 | >1,024 (>8) | >1,024 (>8) | 512 (4) | 128 | 512 (4) | 128 | 256 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 |

| Biocides | |||||||||||||

| Acridine | 512 | 64 | 512 (8) | 256 (4) | 64 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Acriflavine | 64 | 8 | 64 (8) | 64 (8) | 16 | 8 | 32 (4) | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Cristal violet | 32 | 1 | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | 1 | 1 | 4 (4) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ethidium bromide | 1,024 | 64 | 1,024 (16) | 1,024 (16) | 128 | 64 | 256 (4) | 32 | 128 | 256 | 32 | 32 | 64 |

| Rhodamine | >1,024 | 128 | 1,024 (8) | 1,024 (8) | 128 | 128 | 1,024 (8) | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Metals | |||||||||||||

| Copper | 1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| Zinc | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Manganese | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| Silver | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Mercury | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Other | |||||||||||||

| SDS | 1 | 0.004 | 1 (256) | 0.5 (128) | 0.016 (4) | 0.004 | 0.032 (8) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CTAB, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate.

Numbers in boldface are MICs that are significantly different (fold changes of ≥4 are indicated in parentheses) from the MICs of the ΔacrB mutant strain.

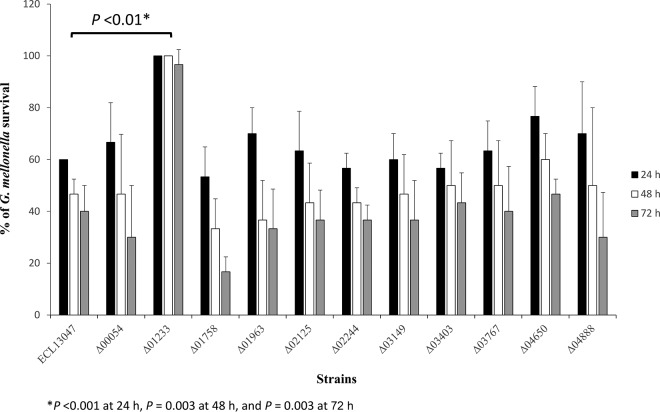

Another interesting feature of AcrAB is its role in the fitness and virulence of E. cloacae, as demonstrated for several other Gram-negative pathogens, such as Salmonella and Klebsiella (15, 26, 32, 33). Pérez and collaborators have shown that the inactivation of acrA or tolC significantly reduced the virulence of E. cloacae clinical isolates in an intraperitoneal mouse model of infection (26). As shown in Fig. 1, the acrB mutant was less virulent than the parental strain in the G. mellonella model. The G. mellonella immune response has strong similarities to the innate immune response of mammals, and this model of infection has been used extensively to evaluate the virulence of both Gram-positive and -negative pathogens (for a review, see references 34 and 35). Indeed, 100% of the larvae infected by the mutant were alive at 72 h postinfection, whereas 60% died when they were infected by the wild-type strain (Fig. 2). The involvement of AcrB in the pathogenicity of E. cloacae did not seemed to be linked to a role in the oxidative stress response or in the resistance to the antimicrobial peptide, since the corresponding mutant was not significantly more sensitive to H2O2 challenge (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) or to the presence of cathepsin E (MIC of 32 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml for the wild-type and ΔacrB strains, respectively), which are deleterious conditions encountered during the infectious process. The other RND pump mutants tested did not show virulence phenotypes altered from that of the parental counterpart (Fig. 2). However, we cannot exclude that some of them could be involved in the infection process that can be observed using other animal models of infection. In Salmonella, the ability to adhere and invade eukaryotic cells of a double mutation in genes encoding efflux pumps was lower than that in single acr mutants (13). Because of the double role of the RND-type pumps in antimicrobial resistance and virulence, it is obvious that such systems have to be privileged targets for the development of clinically usable inhibitors.

FIG 2.

Effect of the deletions of efflux pump-encoding genes on virulence. Percent survival of G. mellonella larvae 24 h (black bars), 48 h (white bars), and 72 h (gray bars) after infection with around 4 × 106 CFU of E. cloacae bacterial cells per larva. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the results represent the means ± standard deviations from live larvae.

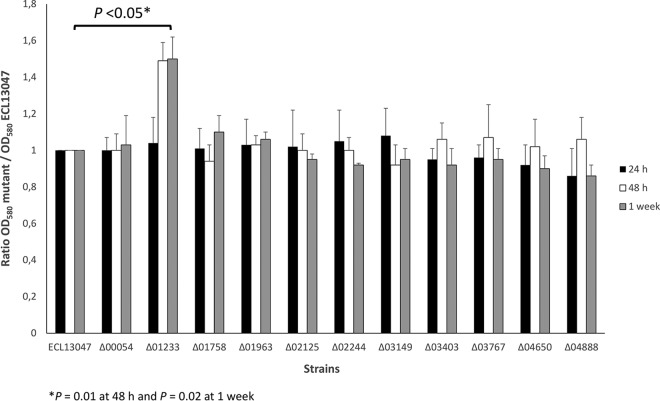

Surprisingly, the acrB deletion mutant (and not the others) seemed able to produce slightly but significantly more biofilm on polystyrene plates than the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). This result appeared contradictory to several studies showing that a defect in efflux activity (by mutation or using efflux inhibitors) impairs biofilm formation (for a review, see reference 15). It is well established that the expression of genes encoding efflux pumps is under tight regulation involving different transcriptional regulators, such as SoxS, RobA, and RamA, in E. cloacae (27). This argues for a general role of efflux pumps in various bacterial physiological processes. In this context, it can be suggested that the regulation leading to biofilm formation and linked to the efflux pumps (and inherent exchanges) in E. cloacae is different from that of E. coli, Klebsiella, or Salmonella (36–38).

FIG 3.

AcrB is involved in the biofilm formation of E. cloacae. The ability of E. cloacae ECL13047 and different mutant strains to form biofilm on polystyrene surfaces after 24 h (black bars), 48 h (white bars), and 1 week (gray bars) of incubation at 37°C is shown. OD values at 580 nm are from three independent experiments, and the means ± standard deviations are presented.

Trans-complementation of the acrB mutant by other RND efflux pumps.

Studies using single-mutant strains clearly highlighted the major role of the AcrAB-TolC system among the numerous RND efflux pumps in intrinsic antimicrobial resistance. However, it is conceivable that the others also are functional, and in the mutant strain background, the loss of one pump may be complemented by one or more still present. This hypothesis was strongly supported by the fact that the antibiotic susceptibility profile of the ΔacrA mutant of E. cloacae EcDC64 was not identical to those observed for the wild type incubated in the presence of Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN), a very well-known EPI in Gram-negative bacteria (20). Moreover, it has been shown that the antimicrobial susceptibility of the ΔacrA mutant was further increased in the presence of PAβN (20). With the aim of evaluating the potential impact of the different systems in resistance to antimicrobial agents, we cloned individually all of the operons containing an RND pump into a multicopy plasmid. These plasmids were then used to assess whether each of the operons was able to complement the ΔacrB hypersusceptible strain.

As expected, the introduction of the acrAB operon (where the RT-quantitative PCR [qPCR] results showed a CT value of 13) into the ΔacrB mutant (where, of course, no transcription was detectable) completely restored the wild-type phenotype (Tables 3 and 4). On the other hand, trans-complementation with the operon ECL_01960-01963, ECL_02243-02244, or ECL_04888-04893 did not modify the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the ΔacrB mutant (Tables 3 and 4). However, it is important to note that the three pumps of ECL_01963, ECL_02244, and ECL_04888 displayed the weakest similarity to AcrB (described above). Experiments carried out with the operons ECL_03401-03404 and ECL_03767 revealed a partial complementation of fusidic acid resistance. In addition, the expression of the ECL_03150-03149 and ECL_04649-04650 operons led to a weak restoration of MICs of benzalkonium chloride and erythromycin, respectively (Tables 3 and 4). It may be concluded that these efflux pumps have the aforementioned molecules as substrates but are not constitutively expressed and are not involved in intrinsic resistance. However, these systems could be inducible by some compounds (antibiotics or not) and even overexpressed in the case of the mutation/inactivation of their local/global regulators, as previously shown for MexCD-OprF and MexEF-OprN efflux systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4).

TABLE 4.

| RND efflux gene | Gene name | Deletion phenotype (agent[s], fold decrease in MIC) | Overexpression phenotype (agent[s], fold increase in MIC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECL_00054 | eefB | No change | NOR (4), LEV (16), CIP (8), MOX (16), TET (4), TIG (8), CHL (16), FA (64), ERY (16), BC (4), CHH (4), TPP (>8), ACR (4), ACF (8), VC (16), EB (16), RHO (8), SDS (128) |

| ECL_01233 | acrB | NOR (4), LEV (4), CIP (2), MOX (8), TET (8), TIG (4), SXT (4), CHL (16), FA (64), ERY (16), BC (4), CHH (2), ACR (16), ACF (8), VC (32), EB (16), RHO (>8), SDS (>64) | NOR (4), LEV (4), CIP (4), MOX (16), TIG (4), SXT (4), CHL (8), FA (64), ERY (16), BC (8), TPP (>8), ACR (8), ACF (8), VC (16), EB (16), RHO (8), SDS (256) |

| ECL_01758 | No change | GMN (4), AKN (4), NOR (4), LEV (8), CIP (8), MOX (32), TET (8), TIG (16), CHL (4), FA (16), ERY (16), TPP (4), SDS (4) | |

| ECL_01963 | cusA | No change | No change |

| ECL_02125 | oqxB | No change | NOR (16), LEV (16), CIP (16), MOX (16), SXT (64), CHL (64), FA (4), BC (4), TPP (4), ACF (4), VC (4), EB (4), RHO (8), SDS (8) |

| ECL_02244 | No change | No change | |

| ECL_03149 | No change | BC (4) | |

| ECL_03403 | mdtC | No change | FA (8) |

| ECL_03767 | No change | FA (16) | |

| ECL_04650 | No change | ERY (4) | |

| ECL_04888 | cusA | No change | No change |

Abbreviations: ACF, acriflavine; ACR, acridine orange; AKN, amikacin; BC, benzalkonium; CHH, chlorhexidine; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP ciprofloxacin; CV, crystal violet; EB, ethidium bromide; ERY, erythromycin; FA, fusidic acid; GMN, gentamicin; LEV, levofloxacin; MOX, moxifloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; RHO, rhodamine; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TET, tetracycline; TIG, tigecycline; TPP, tetraphenylphosphonium.

Interestingly, three constructions (ECL_00053-00055, ECL_01758, and ECL_02124-02125) were able to largely restore the wild-type phenotype. We constructed the ECL_00054, ECL_01758, and ECL_2125 mutant strains in the acrB-deleted background. Except for the ΔacrB/ΔECL_01758 and ΔacrB/ΔECL_02125 strains, which were 4-fold more sensitive to colistin and nitrofurantoin, respectively, than the ΔacrB mutant, the antibiotic resistance profiles of the three double mutants were similar to that of the ΔacrB single mutant (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). This again suggests that the absence of phenotype when these system were individually deleted very likely was due to the compensatory effect of the AcrAB-TolC activity.

The first construction, ECL_00053-00055, the transcription of which was 673-fold higher in the ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55 strain than in the ΔacrB mutant, corresponded to the homologous EefABC efflux pump identified in Enterobacter aerogenes, and the large panel of substrates of this RND system is detailed in Table 4 (39). It has been shown that the overexpression of eefABC in an acrA mutant of E. aerogenes also conferred the restoration of antibiotic MICs (39). In E. aerogenes, this operon is transcriptionally repressed by the H-NS (histone-like nucleoid-structuring) global regulator, and the activation of the eefABC promoter has been detected in chloramphenicol-resistant mutants (28, 39). In the E. cloacae genome, this operon was preceded by a gene coding for a TetR family transcriptional regulator (Fig. 1), the corresponding mutant of which seemed impaired in the colonization of G. mellonella and stimulated the expression of eefABC (unpublished results).

The second construction was ECL_01758, which complemented the hypersusceptibility phenotype of the acrB mutant, except in the cases of co-trimoxazole, benzalkonium chloride, and all biocides (Table 3). RT-qPCR results revealed that the transcription of ECL_01758 was 616-fold induced in the ΔacrB/ECL_01758 strain. Astonishingly, this transporter was annotated as an acridine efflux pump, whereas its expression did not increase resistance to this molecule (21). One of the most spectacular effects of the expression of ECL_01758 in the acrB mutant was the 4-fold increase of MICs of aminoglycosides (except tobramycin) that were not modified by the acrB deletion (Tables 3 and 4). These data showed that ECL_01758, when strongly expressed in the cell, can be part of the bacterial arsenal for developing resistance, especially to gentamicin and amikacin. Contrary to what we observed in the acrB mutant, Pérez et al. showed modest decreases in the MICs of aminoglycosides in the acrA mutant of E. cloacae (27). It has been reported that the overexpression of MexY correlated with decreased susceptibility to aminoglycosides of P. aeruginosa and that the RND protein AdeB of Acinetobacter baumannii was responsible for aminoglycoside resistance (40, 41). Interestingly, ECL_01758 was found to be the polypeptide most homologous to AdeB (58% identity and 76% similarity). Moreover, in the strain overexpressing ECL_01758, MICs of moxifloxacin and tigecycline were 4-fold higher than those of the wild-type strain (Table 3). Thus, it appeared that, in addition to the AcrAB pump, ECL_01758 and ECL_00054 had tigecycline as the substrate (Table 4). This is of clinical importance for the control of the emergence of tigecycline-resistant strains, since this molecule is increasingly used to fight against MDR Enterobacter (42–44)

Lastly, the plasmid carrying ECL_02124-02125 (annotated as oqxAB genes and transcriptionally induced 743-fold) restored the wild-type phenotype, except for tetracycline, tigecycline, erythromycin, and acridine orange (Tables 3 and 4). The MICs of the fluoroquinolones tested (except moxifloxacin) were even 4-fold higher than those of the wild-type strain (Tables 3 and 4). Similarly, MICs of co-trimoxazole and chloramphenicol were 16- and 4-fold higher in the acrB mutant harboring the ECL_02124-02125 operon than in the parental strain, respectively (Tables 3 and 4). It appears that this RND efflux system, when overexpressed by deregulation, can participate in reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, co-trimoxazole, and chloramphenicol. In this context, it has been shown that the oqxAB chromosomal operon of K. pneumonia can become plasmid borne by transposition, leading to its overexpression and consequently exhibiting an MDR phenotype (45).

The susceptibility to levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol of ECL13047 significantly increased in the presence of PAβN (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). In addition, this EPI reduced the MICs to these antimicrobial molecules for the ΔacrB/ECL_00053-55, ΔacrB/ECL_01758, and ΔacrB/ECL_02124-25 trans-complemented strains (see Table S3), showing that the corresponding pumps also were targets of the inhibitor.

The present study confirmed the crucial role of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence of E. cloacae but also suggested that other operon-containing genes encoding RND efflux pump-mediated mechanisms complement, superadd to, and extend the range of antibiotic resistance. Besides AcrAB-TolC, it is probable that other members of the RND family are involved in the acquisition of additional resistance types (especially through overexpression), which may have an impact on opportunistic traits of E. cloacae. These results highlight the importance of pursuing the development of EPIs, especially those directed against the AcrB transporter.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Michel Auzou, Brigitte Belin, Mamadou Godet, Sébastien Galopin, and Isabelle Rincé is gratefully appreciate.

All authors read and approved the manuscript and have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02840-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nikaido H. 1996. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 178:5853–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putman M, van Veen HW, Konings WN. 2000. Molecular properties of bacterial multidrug transporters. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:672–693. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.672-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole K, Krebes K, McNally C, Neshat S. 1993. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J Bacteriol 175:7363–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li XZ, Plésiat P, Nikaido H. 2015. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:337–418. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zgurskaya HI, Nikaido H. 1999. Bypassing the periplasm: reconstitution of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:7190–7195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aires JR, Nikaido H. 2005. Aminoglycosides are captured from both periplasm and cytoplasm by the AcrD multidrug efflux transporter of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 187:1923–1929. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.1923-1929.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikaido H, Takatsuka Y. 2009. Mechanisms of RND multidrug efflux pumps. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukagoshi N, Aono R. 2000. Entry into and release of solvents by Escherichia coli in an organic-aqueous two-liquid-phase system and substrate specificity of the AcrAB-TolC solvent-extruding pump. J Bacteriol 182:4803–4810. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.17.4803-4810.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pos KM. 2009. Drug transport mechanism of the AcrB efflux pump. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:782–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma D, Cook DN, Hearst JE, Nikaido H. 1994. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol 2:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(94)90654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piddock LJ. 2006. Multi-resistance efflux pumps–not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:629–636. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez JL, Sanchez MB, Martinez-Solano L, Hernandez A, Garmendia L, Fajardo A, Alvarez-Ortega C. 2009. Functional role of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps in microbial natural ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:430–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair JM, Smith HE, Ricci V, Lawler AJ, Thompson LJ, Piddock LJ. 2015. Expression of homologous RND efflux pump genes is dependent upon AcrB expression: implications for efflux and virulence inhibitor design. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:424–431. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikaido H, Pagès JM. 2012. Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:340–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun J, Deng Z, Yan A. 2014. Bacterial multidrug efflux pumps: mechanisms, physiology and pharmacological exploitations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 453:254–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders WE, Sanders CC. 1997. Enterobacter spp.: pathogens poised to flourish at the turn of the century. Clin Microbiol Rev 10:220–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández-Baca Ballesteros VF, Hervás JA, Villalón P, Domínguez MA, Benedí VJ, Albertí S. 2001. Molecular epidemiological typing of Enterobacter cloacae isolates from a neonatal intensive care unit: three-year prospective study. J Hosp Infect 49:173–182. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roehrborn A, Thomas L, Potreck O, Ebener C, Ohmann C, Goretzki PE, Röher HD. 2001. The microbiology of postoperative peritonitis. Clin Infect Dis 33:1513–1519. doi: 10.1086/323333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guérin F, Isnard C, Cattoir V, Giard JC. 2015. Complex regulation pathways of AmpC-mediated β-lactam resistance in Enterobacter cloacae complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:7753–7761. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01729-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez A, Canle D, Latasa C, Poza M, Beceiro A, Tomás Mdel M, Fernández A, Mallo S, Pérez S, Molina F, Villanueva R, Lasa I, Bou G. 2007. Cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and analysis of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump of Enterobacter cloacae and determination of its involvement in antibiotic resistance in a clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3247–3253. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00072-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren Y, Ren Y, Zhou Z, Guo X, Li Y, Feng L, Wang L. 2010. Complete genome sequence of Enterobacter cloacae subsp. cloacae type strain ATCC 13047. J Bacteriol 192:2463–2464. doi: 10.1128/JB.00067-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guérin F, Lallement C, Isnard C, Dhalluin A, Cattoir V, Giard J-C. 2015. Abstr 55th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, abstr C-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derbise A, Lesic B, Dacheux D, Ghigo JM, Carniel E. 2003. A rapid and simple method for inactivating chromosomal genes in Yersinia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 38:113–116. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doublet B, Douard G, Targant H, Meunier D, Madec JY, Cloeckaert A. 2008. Antibiotic marker modifications of lambda Red and FLP helper plasmids, pKD46 and pCP20, for inactivation of chromosomal genes using PCR products in multidrug-resistant strains. J Microbiol Methods 75:359–361. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez A, Poza M, Aranda J, Latasa C, Medrano FJ, Tomás M, Romero A, Lasa I, Bou G. 2012. Effect of transcriptional activators SoxS, RobA, and RamA on expression of multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6256–6266. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01085-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez A, Poza M, Fernández A, Fernández Mdel C, Mallo S, Merino M, Rumbo-Feal S, Cabral MP, Bou G. 2012. Involvement of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in the resistance, fitness, and virulence of Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2084–2090. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05509-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masi M, Pagès JM, Pradel E. 2006. Production of the cryptic EefABC efflux pump in Enterobacter aerogenes chloramphenicol-resistant mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother 57:1223–1226. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su CC, Li M, Gu R, Takatsuka Y, McDermott G, Nikaido H, Yu EW. 2006. Conformation of the AcrB multidrug efflux pump in mutants of the putative proton relay pathway. J Bacteriol 188:7290–7296. doi: 10.1128/JB.00684-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takatsuka Y, Nikaido H. 2006. Threonine-978 in the transmembrane segment of the multidrug efflux pump AcrB of Escherichia coli is crucial for drug transport as a probable component of the proton relay network. J Bacteriol 188:7284–7289. doi: 10.1128/JB.00683-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blair JM, Bavro VN, Ricci V, Modi N, Cacciotto P, Kleinekathöfer U, Ruggerone P, Vargiu AV, Baylay AJ, Smith HE, Brandon Y, Galloway D, Piddock LJ. 2015. AcrB drug-binding pocket substitution confers clinically relevant resistance and altered substrate specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:3511–3516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419939112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blair JM, La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ, Piddock LJ. 2009. Periplasmic adaptor protein AcrA has a distinct role in the antibiotic resistance and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:965–972. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padilla E, Llobet E, Doménech-Sánchez A, Martínez-Martínez L, Bengoechea JA, Albertí S. 2010. Klebsiella pneumoniae AcrAB efflux pump contributes to antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:177–183. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00715-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glavis-Bloom J, Muhammed M, Mylonakis E. 2012. Of model hosts and man: using Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and Galleria mellonella as model hosts for infectious disease research. Adv Exp Med Biol 710:11–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5638-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumura K, Furukawa S, Ogihara H, Morinaga Y. 2011. Roles of multidrug efflux pumps on the biofilm formation of Escherichia coli K-12. Biocontrol Sci 16:69–72. doi: 10.4265/bio.16.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kvist M, Hancock V, Klemm P. 2008. Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7376–7382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01310-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baugh S, Ekanayaka AS, Piddock LJ, Webber MA. 2012. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2409–2417. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masi M, Pagès JM, Villard C, Pradel E. 2005. The eefABC multidrug efflux pump operon is repressed by H-NS in Enterobacter aerogenes. J Bacteriol 187:3894–3897. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3894-3897.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam S, Oh H, Jalal S, Karpati F, Ciofu O, Høiby N, Wretlind B. 2009. Chromosomal mechanisms of aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 15:60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T. 2001. Resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pump involved in aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strain BM4454. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:3375–3380. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3375-3380.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daurel C, Fiant AL, Brémont S, Courvalin P, Leclercq R. 2009. Emergence of an Enterobacter hormaechei strain with reduced susceptibility to tigecycline under tigecycline therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4953–4954. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01592-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hornsey M, Ellington MJ, Doumith M, Scott G, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Emergence of AcrAB-mediated tigecycline resistance in a clinical isolate of Enterobacter cloacae during ciprofloxacin treatment. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:478–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veleba M, De Majumdar S, Hornsey M, Woodford N, Schneiders T. 2013. Genetic characterization of tigecycline resistance in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1011–1018. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong MH, Chan EW, Chen S. 2015. Evolution and dissemination of OqxAB-like efflux pumps, an emerging quinolone resistance determinant among members of Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3290–3297. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00310-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.