Abstract

Here, we report two Enterobacter cloacae sequence type 231 isolates coproducing KPC-3 and NDM-1 that have caused lethal infections in a tertiary hospital in China. The blaNDM-1-harboring plasmids carry IncA/C2 and IncR replicons, showing a mosaic plasmid structure, and the blaNDM-1 is harbored on a novel class I integron-like element. blaKPC-3 is located on a Tn3-ΔblaTEM-1-blaKPC-3-ΔTn1722 element, flanked by two 9-bp direct-repeat sequences and harbored on an IncX6 plasmid.

TEXT

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains have spread worldwide and have become a significant public health threat (1, 2). It is alarming that CRE isolates coproducing multiple carbapenemases recently emerged and pose significant challenges to our limited treatment strategies, as these bacteria tend to be extremely highly resistant (3–10). To date, the coexistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase 2 (KPC-2) and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) in single clinical isolates from different species, including K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter hormaechei, and Citrobacter freundii, has been reported in Brazil, India, Pakistan, and China (3–6, 8, 9). However, knowledge regarding the genetic content and plasmid structure of these multicarbapenemase-producing bacteria remains limited (3, 6). In this study, we used next-generation sequencing to characterize the genomes of two KPC-3– and NDM-1–coproducing E. cloacae strains and their plasmids. Our analysis revealed distinct plasmid structures that, to our knowledge, have not been described previously.

Two carbapenem-resistant E. cloacae strains (SZECL1 and SZECL2) were identified in a retrospective study on CRE at a tertiary-care hospital in China. They were isolated from sputum samples from two female patients (63 and 57 years old) admitted to the same intensive care unit in 2012. The two isolates were collected 11 days apart. The patients died 13 and 18 days after the isolation of the organisms as a result of severe pulmonary infections. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that the two isolates, SZECL1 and SZECL2, had the same resistance profile (Table 1). They were resistant to all β-lactams and inhibitors, including imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and ceftazidime-avibactam, and were resistant to amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole but remained susceptible to tetracycline, tigecycline, and colistin.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of E. cloacae isolates and their E. coli DH10B transformantsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) forb: |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP | MEM | ERT | TZP | AMC | CFZ | CAZ | CXM | FOX | CTX | FEP | ATM | CTX/CA | CAZ/AVI | AMK | GEN | CIP | LVX | SXT | TET | TGC | CST | |

| SZECL1 | >8 | >8 | >4 | >64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >32 | >16 | >16 | >4 | >16 | >32 | >8 | >2 | >4 | >2/38 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

| SZECL2 | >8 | >8 | >4 | >64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >32 | >16 | >16 | >4 | >16 | >32 | >8 | >2 | >4 | >2/38 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

| SZECL1T-NDM | 4 | 4 | >4 | 64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >32 | 16 | ≤4 | >4 | >16 | >32 | >8 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | >2/38 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

| SZECL1T-KPC | 8 | 4 | >4 | >64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 16 | >32 | >16 | >16 | 4 | 4 | ≤8 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5/9.5 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

| SZECL2T-NDM | 4 | 8 | >4 | 64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >32 | 16 | ≤4 | >4 | >16 | >32 | >8 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | >2/38 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

| SZECL2T-KPC | 4 | 4 | >4 | >64 | >16/8 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 16 | >32 | 16 | >16 | 4 | 4 | ≤8 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5/9.5 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 |

Susceptibility to colistin and ceftazidime-avibactam were examined by broth microdilution. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the other agents was performed with the MicroScan WalkAway plus system.

IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; ERT, ertapenem; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, CFZ, cefazolin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CXM, cefuroxime, FOX, cefoxitin, CTX, cefotaxime, FEP, cefepime, ATM, aztreonam, CA, clavulanate; AVI, avibactam; AMK, amikacin, GEN, gentamicin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LVX, levofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TET, tetracycline; TGC, tigecycline; CST, colistin.

Genotyping results showed that SZECL1 carries blaKPC-3, blaNDM-1, and blaACT-16, while SZECL2 harbors the same β-lactamase genes (blaKPC-3, blaNDM-1, and blaACT-16) as SZECL1, with an additional blaCTX-M-15 gene (11, 12). Multilocus sequence typing indicated that the two isolates were of the same sequence type, ST231 (13), and they displayed indistinguishable patterns in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis, suggesting that these two isolates are closely related and may have evolved from the same ancestor.

The blaKPC-3-harboring plasmids in SZECL1 and SZECL2 were successfully transferred to the recipient strain, Escherichia coli J53 Azr; however, we were unable to transfer the blaNDM-1-harboring plasmids by conjugation (14). Consequently, the plasmid DNA from the two strains were extracted and electroporated into E. coli strain DH10B. Transformants with a single blaKPC-3- or blaNDM-1-harboring plasmid from SZECL1 (namely, SZECL1T-KPC and SZECL1T-NDM) and SZECL2 (namely, SZECL2T-KPC and SZECL2T-NDM) were selected for susceptibility testing and complete plasmid sequencing using a previously described method (15). The susceptibility testing confirmed the successful transfer of carbapenem resistance from the parental strains to the recipient strain, E. coli DH10B (Table 1).

The blaNDM-1-harboring plasmid in SZECL1, pNDM1_SZ1, is 130,573 bp long, has an average G+C content of 52.3%, and harbors 164 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1A). pNDM1_SZ1 harbors a wide array of resistance genes, including blaNDM-1 (β-lactamase), bleMBL (bleomycin), strA, strB, aadA2, and armA (aminoglycosides), mph2 and mel (macrolides), sul1 and sul2 (sulfonamides), dfrA12 (trimethoprim), qacEΔ1 (quaternary ammonium compounds), and the mer operon, which encodes resistance to the heavy metal mercury. In silico plasmid replicon analysis revealed that pNDM1_SZ1 carries two different replicons, IncA/C2 and IncR.

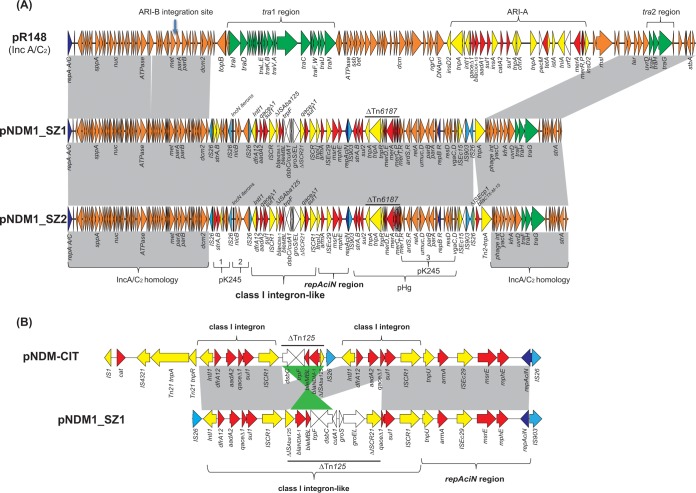

FIG 1.

(A) Structures of plasmids pNDM1-SZ1 and pNDM1-SZ2 and IncA/C2 prototype plasmid pR148. (B) blaNDM-1-harboring and repAciN regions in pNDM1_SZ1 and pNDM-CIT. Gray shading denotes shared regions of homology, while green shading indicates inversely displayed regions of homology. Open reading frames (ORFs) are portrayed by arrows and are colored based on predicted gene function. Genes associated with the tra locus are indicated by green arrows, while replication-associated genes are denoted by dark blue arrows. Resistance genes are indicated by red arrows, while accessory genes are indicated by yellow arrows. IS26 and IS903 are highlighted by light blue arrows. Brown arrows indicate plasmid backbone genes, and white arrows show other genes in the recombination region.

pNDM1_SZ1 harbors an ∼58-kb region nearly identical (>99.9% nucleotide identities) to that of several type 1 IncA/C2 plasmids, including the prototype plasmid pRMH760 (16) and p148 (17). IncA/C2 plasmids typically carry a single replicon gene (repA), two tra regions (tra1 and tra2 regions), and one or two antibiotic resistance islands (ARI-A and ARI-B) (Fig. 1A) (16). ARI-A and ARI-B usually integrate into the IncA/C2 plasmid backbone at two conserved sites, the region upstream of the gene rhs (ARI-A integration) and the region upstream of the gene parA (ARI-B integration) (Fig. 1) (16). Among blaNDM-harboring IncA/C2 plasmids, blaNDM genes are located mainly on the ARI-A but have different neighboring genes and overall organizations (16). In pNDM1_SZ1, the ARI-A and tra1 regions, as well as an ∼30-kb IncA/C2 backbone region, are deleted and replaced by the integration of an ∼73-kb blaNDM-1-containing region (Fig. 1A). Existence of the incomplete tra region is consistent with our inability to move pNDM1_SZ1 in the laboratory by conjugation.

The region in pNDM1_SZ1 that is not related to the IncA/C2 plasmid is highly mosaic and displayed sequence homology to several unrelated plasmids, including pK245 (18) and pHg (also named pKpn2146b) (19) (Fig. 1A). pNDM1_SZ1 has three regions similar to those of pK245 (pK245-1, pK245-2, and pK245-3), the prototype IncR plasmid (Fig. 1A). The first pK245-like region (pK245-1), which contains the streptomycin resistance genes strA and strB, is located downstream of the IncA/C2 plasmid homologous region and is flanked by two directly repeated copies of IS26. The second pK245-like region (pK245-2), including the IncN rep integron-repeat region and three hypothetical protein genes, is located downstream of pK245-1 and is flanked by two inversely oriented IS26 elements. The third pK245-like region (pK245-3) is ∼14 kb and harbors an intact IncR plasmid replication and partitioning locus, including the IncR replicon gene repB, the plasmid-partitioning protein genes parA and parB, the error-prone repair protein genes umuC and umuD, and the antirestriction protein genes ardS and ardR, located ∼40 kb downstream of pK245-2 (Fig. 1A). Notably, the pK245-3 region on pNDM1_SZ1 has also been found on plasmid pHg, isolated from the NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae BAA-2146 (19). pHg harbors an ∼27-kb region homologous to pNDM1_SZ1, including the above-described pK245-3 region, a ΔTn6187-containing mer operon, and an strAB-sul2 locus. Interestingly, this pHg-like region, along with its downstream toxin-antitoxin gene vagCD, ISEc15, and a putative ATP-dependent Lon protease gene lon, are flanked by two directly repeated copies of IS903, suggesting that pNDM1_SZ1 may have acquired this region from a pHg-like plasmid through an IS903-mediated transposition and homologous recombination.

The blaNDM-1 gene in pNDM1_SZ1 is harbored by a novel class 1 integron-like element located immediately upstream of the repAciN region (Fig. 1A and B). The blaNDM-1-containing integron and repAciN region are flanked by IS26 (downstream pK245-2 region) and IS903 (upstream pHg-like region) elements and span ∼25 kb. The integron-like element starts with intl1, a dfrA12-aadA2 cassette, the 3′-CS region (qacEΔ1 and sul1), and ISCR1, followed by a truncated Tn125 harboring blaNDM-1, the second copy of ΔqacEΔ1 and sul1, and ISCR1. The truncated Tn125 contains the following ordered genes: ΔISAba125, blaNDM-1, bleMBL, trpF, dsbC, cutA1, groS, gorEL, and ΔISCR21. The upstream Tn125 (at ISAba125) is disrupted by the first copy of ISCR1, while the downstream Tn125 (at ISCR21) is truncated by the second copy of the 3′-CS region (ΔqacEΔ1 and sul1). Downstream of the blaNDM-1-containing integron-like element is the repAciN region with a Tn1548::armA-mel-mph2-repAciN module encoding high-level resistance to aminoglycosides and macrolides. The overall structure of the integron-like and repAciN region is similar to that of the IncHI1 plasmid pNDM-CIT from a C. freundii isolate collected from a patient traveling from India (20, 21) (Fig. 1B). In pNDM-CIT, blaNDM-1 is harbored by a differently ordered ΔTn125 (dsbC-trpF-bleMBL-blaNDM-1- ΔISAba125) and flanked by two class I integrons. It is likely that the region in pNDM1_SZ1 originated from a similar element with duplicated class 1 integrons flanking the ΔTn125, followed by deletion of the intl1-dfrA12-aadA2 region in the second copy of the integron. The flanked upstream IS26 and downstream IS903 also suggest that this region is probably acquired by an IS-mediated homologous recombination event.

The blaNDM-1-harboring plasmid in SZECL2, pNDM1_SZ2, was also completely sequenced, and it is 132,232 bp long. In comparison to pNDM1_SZ1, pNDM1_SZ2 harbors an additional ΔISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 module, while the rest of the sequences are identical to those in pNDM1_SZ1 (Fig. 1A).

The blaKPC-3-harboring plasmids in SZECL1 and SZECL2 are identical (namely, pKPC3_SZ) and are 43,333 bp long and have a G+C content of 54.1%. In silico plasmid replicon analysis cannot assign it into any known Inc group. A BLAST search of the core plasmid region against those in GenBank failed to identify any homologous sequences in the database, suggesting that pKPC3_SZ is a novel plasmid group that has not been described previously. Further examination of the plasmid structure revealed that the core genes in pKPC3_SZ carry a pir-bis-par-hns-topB-pilX-actX-taxCA synteny that is the same as that in multiple IncX plasmids (14, 22) (Fig. 2A).

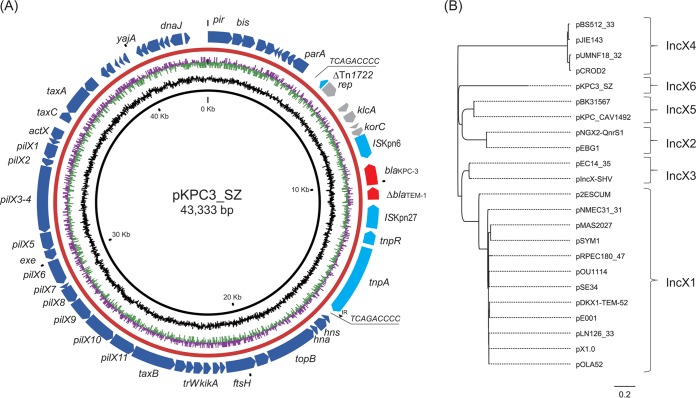

FIG 2.

(A) Structure of plasmid pKPC3_SZ. Open reading frames (ORFs) are indicated by arrows, with backbone-region ORFs in blue and acquired-region ORFs in gray. Resistance genes are depicted by red arrows, while transposonase genes are shown with light blue arrows. The 9-bp direct-repeat sequences are underlined, and the small black arrow denotes the downstream invert-repeat (IR) of Tn3. (B) Phylogenetic maximum-likelihood tree of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from backbone sequences of 23 IncX plasmids.

Currently, five subgroups of IncX plasmids (IncX1 to IncX5) have been described (14, 22). The gene taxC is conserved among different IncX plasmids and has been used to identify and subgroup IncX plasmids (IncX1 to IncX5). The taxC genes of plasmids from different incompatibility subgroups (e.g., IncX1 to IncX5) share between 37% and 92% nucleotide identity, whereas those within a given incompatibility subgroup share between 92% and 99% nucleotide identity (14, 22). A comparison of the taxC gene in pKPC3_SZ to those of the IncX plasmids depicted in Fig. 2B showed 37% to 50% nucleotide identity, suggesting that plasmid pKPC3_SZ belongs to a novel IncX subgroup. Phylogenetic analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the conserved regions of 23 plasmids was used to explore further the relationship between pKPC3_SZ and other IncX plasmids (Fig. 2B) (14). The results clearly divided the IncX plasmids into six subgroups, with pKPC3_SZ clustering separately from the aforementioned subgroups IncX1 to IncX5. Therefore, pKPC3_SZ is classified as a previously unknown plasmid subgroup of IncX6.

The blaKPC-3 gene is harbored by a 10,756-bp Tn3-ΔblaTEM-1-blaKPC-3-ΔTn1722 element, flanked by two 9-bp putative direct-repeat sequences (TCAGACCCC) and integrated downstream of parA (Fig. 2A). BLAST results showed that this region is highly similar to those of the blaKPC-2-harboring element in pKPC2-EC14653 (>99% identities and >98% query coverage) (3) and pN6 (>99% identities and >99% query coverage; GenBank accession number KC355363). The major difference between pKPC3_SZ and the other two plasmids is that they carry different blaKPC alleles and the presence of putative direct repeat sequences. In this study, the Tn1722 was found to be truncated, and 9-bp direct-repeat sequences were identified upstream of ΔTn1722. The downstream 9-bp direct repeat was located at the distal terminus of the 38-bp invert repeat of Tn3 (Fig. 2A). Our finding suggests that homologous recombination may contribute to the integration of blaKPC-3-harboring elements in the backbone of pKPC3_SZ.

The genome of SZECL1 was also subject to whole-genome sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq system, which resulted in 29 contigs, ranging from 655 to 1,425,454 bp, with a total length of 4,893,955 bp. The quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) genes gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE were further examined, and we observed mutations encoding amino acid substitutions at Ser83-Phe and Asp87-Ala within the QRDRs of GyrA and Ser80-Ile in ParC. Examination of the outer membrane protein OmpF and OmpC genes revealed a premature stop codon at AA57 in OmpF due to a cytosine-to-adenine mutation at nucleotide 171.

Altogether, this study characterizes two multidrug-resistant E. cloacae strains carrying blaKPC-3, blaNDM-1, armA, QRDR mutations, and outer membrane porin loss, conferring high-level resistance to all β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first genomic study of clinical isolates that coexpress KPC-3 and NDM-1. blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-3 were harbored by unique genetic elements on previously unknown plasmids, which demonstrates their genomic plasticity, their rapid evolution, and the dissemination of these carbapenemase genes.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The draft genome sequence of E. cloacae strain SZECL1 has been deposited in the GenBank whole-genome shotgun database under accession number LKUI00000000. The complete nucleotide sequences of plasmids pKPC3_SZ, pNDM1_SZ1, and pNDM1_SZ2 have been deposited under GenBank accession numbers KU302800 to KU302802.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI090155 and R21AI117338 and National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81572032.

B.N.K. holds two patents that focus on using DNA sequencing to identify bacterial pathogens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2014. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:821–830. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Mathema B, Chavda KD, DeLeo FR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol 22:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu W, Feng Y, Carattoli A, Zong Z. 2015. Characterization of an Enterobacter cloacae strain producing both KPC and NDM carbapenemases by whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6625–6628. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quiles MG, Rocchetti TT, Fehlberg LC, Kusano EJ, Chebabo A, Pereira RM, Gales AC, Pignatari AC. 2015. Unusual association of NDM-1 with KPC-2 and armA among Brazilian Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Braz J Med Biol Res 48:174–177. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20144154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira PS, Borghi M, Albano RM, Lopes JC, Silveira MC, Marques EA, Oliveira JC, Asensi MD, Carvalho-Assef AP. 2015. Coproduction of NDM-1 and KPC-2 in Enterobacter hormaechei from Brazil. Microb Drug Resist 21:234–236. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J, Qiu Y, Yin Z, Chen W, Yang H, Yang W, Wang J, Gao Y, Zhou D. 2015. Coexistence of a novel KPC-2-encoding MDR plasmid and an NDM-1-encoding pNDM-HN380-like plasmid in a clinical isolate of Citrobacter freundii. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2987–2991. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zowawi HM, Sartor AL, Balkhy HH, Walsh TR, Al Johani SM, AlJindan RY, Alfaresi M, Ibrahim E, Al-Jardani A, Al-Abri S, Al Salman J, Dashti AA, Kutbi AH, Schlebusch S, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2014. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the countries of the Gulf cooperation council: dominance of OXA-48 and NDM producers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3085–3090. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02050-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattar H, Toleman M, Nahid F, Zahra R. 19 November 2014. Co-existence of bla and bla in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Pakistan. J Chemother doi: 10.1179/1973947814Y.0000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumarasamy K, Kalyanasundaram A. 2012. Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate co-producing NDM-1 with KPC-2 from India. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:243–244. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazi M, Shetty A, Rodrigues C. 2015. The carbapenemase menace: do dual mechanisms code for more resistance? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 36:116–117. doi: 10.1017/ice.2014.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans SR, Hujer AM, Jiang H, Hujer KM, Hall T, Marzan C, Jacobs MR, Sampath R, Ecker DJ, Manca C, Chavda K, Zhang P, Fernandez H, Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Hill CB, Perez F, Caliendo A, Fowler VG, Chambers HF, Kreiswirth BN, Bonomo RA. 2016. Rapid molecular diagnostics, antibiotic treatment decisions, and developing approaches to inform empiric therapy: PRIMERS I and II. Clin Infect Dis 62:181–199. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Endimiani A, Rosenthal ME, Zhao Y, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2011. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection and classification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene (blaKPC) variants. J Clin Microbiol 49:579–585. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01588-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. 2013. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for characterization of Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS One 8:e66358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Chavda KD, Fraimow HS, Mediavilla JR, Melano RG, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2013. Complete nucleotide sequences of blaKPC-4- and blaKPC-5-harboring IncN and IncX plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in New Jersey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:269–276. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01648-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Hu H, Chavda KD, Zhao S, Liu R, Liang H, Zhang W, Wang X, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Complete sequence of a KPC-producing IncN multidrug-resistant plasmid from an epidemic Escherichia coli sequence type 131 strain in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2422–2425. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02587-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harmer CJ, Hall RM. 2014. pRMH760, a precursor of A/C(2) plasmids carrying blaCMY and blaNDM genes. Microb Drug Resist 20:416–423. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Castillo CS, Hikima J, Jang HB, Nho SW, Jung TS, Wongtavatchai J, Kondo H, Hirono I, Takeyama H, Aoki T. 2013. Comparative sequence analysis of a multidrug-resistant plasmid from Aeromonas hydrophila. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:120–129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01239-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YT, Shu HY, Li LH, Liao TL, Wu KM, Shiau YR, Yan JJ, Su IJ, Tsai SF, Lauderdale TL. 2006. Complete nucleotide sequence of pK245, a 98-kilobase plasmid conferring quinolone resistance and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase activity in a clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:3861–3866. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00456-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson CM, Bent ZW, Meagher RJ, Williams KP. 2014. Resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements of an NDM-1-encoding Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. PLoS One 9:e99209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirel L, Ros A, Carricajo A, Berthelot P, Pozzetto B, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. 2011. Extremely drug-resistant Citrobacter freundii isolate producing NDM-1 and other carbapenemases identified in a patient returning from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:447–448. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01305-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolejska M, Villa L, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Carattoli A. 2013. Complete sequencing of an IncHI1 plasmid encoding the carbapenemase NDM-1, the ArmA 16S RNA methylase and a resistance-nodulation-cell division/multidrug efflux pump. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:34–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson TJ, Bielak EM, Fortini D, Hansen LH, Hasman H, Debroy C, Nolan LK, Carattoli A. 2012. Expansion of the IncX plasmid family for improved identification and typing of novel plasmids in drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Plasmid 68:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]