Abstract

Francisella tularensis causes tularemia and is a potential biothreat. Given the limited antibiotics for treating tularemia and the possible use of antibiotic-resistant strains as a biowarfare agent, new antibacterial agents are needed. AR-12 is an FDA-approved investigational new drug (IND) compound that induces autophagy and has shown host-directed, broad-spectrum activity in vitro against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and F. tularensis. We have shown that AR-12 encapsulated within acetalated dextran (Ace-DEX) microparticles (AR-12/MPs) significantly reduces host cell cytotoxicity compared to that with free AR-12, while retaining the ability to control S. Typhimurium within infected human macrophages. In the present study, the toxicity and efficacy of AR-12/MPs in controlling virulent type A F. tularensis SchuS4 infection were examined in vitro and in vivo. No significant toxicity of blank MPs or AR-12/MPs was observed in lung histology sections when the formulations were given intranasally to uninfected mice. In histology sections from the lungs of intranasally infected mice treated with the formulations, increased macrophage infiltration was observed for AR-12/MPs, with or without suboptimal gentamicin treatment, but not for blank MPs, soluble AR-12, or suboptimal gentamicin alone. AR-12/MPs dramatically reduced the burden of F. tularensis in infected human macrophages, in a manner similar to that of free AR-12. However, in vivo, AR-12/MPs significantly enhanced the survival of F. tularensis SchuS4-infected mice compared to that seen with free AR-12. In combination with suboptimal gentamicin treatment, AR-12/MPs further improved the survival of F. tularensis SchuS4-infected mice. These studies provide support for Ace-DEX-encapsulated AR-12 as a promising new therapeutic agent for tularemia.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis, which causes the life-threatening disease tularemia in humans and animals, is one of the most infectious bacterial pathogens known (1). Four different subspecies of Francisella have been classified: F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (type A), F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (type B), F. tularensis subsp. novicida, and F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica. Among the four subspecies, F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (type A) is the most virulent in humans and is found largely throughout North America and in some parts of Europe (1). Disease caused by the other three subspecies is limited primarily to immunocompromised individuals. The F. tularensis SchuS4 (type A prototype) strain has an infectious dose of fewer than 25 bacteria and a mortality rate of 30 to 60% for untreated pneumonic infections (2, 3). Tularemia is considered to be a reemerging disease, with recent outbreaks reported worldwide, including in the United States (4, 5). Because of the ease of aerosol transmission, F. tularensis could be transmitted deliberately, resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality on a large scale. It has therefore been recognized as a potential biological warfare agent and is classified in tier 1, the highest-level tier for bioterrorism agents classified by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1, 3).

Although a live attenuated vaccine strain (LVS) of F. tularensis has been used in humans (6), there is no currently licensed U.S. vaccine. Moreover, antibiotic treatment of tularemia is limited to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin), and tetracyclines (7). At present, there is no naturally acquired resistance to these antibiotics in human/environmental isolates of F. tularensis (8). However, constant exposure of this bacterium to increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin in vitro can select for resistant strains, including those cross-resistant to other clinically relevant antibiotics, including other fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides (9). Additionally, subspecies of F. tularensis have different antibiotic sensitivities, making treatment more complicated (10). Even with antibiotic treatment, many therapeutic failures and relapses have been reported (11, 12). Given these issues, the development of new antibacterial agents with novel mechanisms of action against F. tularensis has become a priority. Indeed, novel therapeutic approaches have been explored in recent years (7), including the use of newer antibiotics (e.g., tigecycline, ketolides, and fluoroquinolones), improving antibiotic delivery in vivo (e.g., liposome delivery), enhancement of the innate immune response by use of antimicrobial peptides, and combinatorial approaches with conventional antibiotics and immune adjuvants (7, 13).

F. tularensis is difficult to treat because it is a facultative intracellular bacterium that targets macrophages and has several mechanisms that enable it to evade immune clearance. Upon host cell entry, the bacterium affects signaling cascades to limit host protective inflammatory responses, block fusion of Francisella-containing phagosomes with lysosomes, and escape into the cytosol to proliferate, which results in host cell death (14–19). Several hours after entry into the cytoplasm, subsets of wild-type Francisella organisms and bacterial mutants that are incapable of escaping from phagosomes have been observed in double-membrane vacuoles with markers of autophagosomes (20, 21). The relative importance of autophagy in controlling Francisella infection in macrophages remains uncertain, depending on the macrophage cell type and the bacterial strain. Evidence exists for Francisella escape from autophagy mechanisms and for ATG5-independent autophagy increasing F. tularensis survival (22, 23).

One agent that has been shown to promote autophagy is AR-12. AR-12 (also known as OSU-03012; Arno Therapeutics) is an approved derivative (as an investigational new drug [IND]) of celecoxib that lacks cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor activity. It has been investigated as an anticancer agent that suppresses tumor cell viability through multiple mechanisms, including the induction of autophagy (24–26). We have shown that AR-12 enhances the clearance of the intracellular bacterial pathogens Salmonella and Francisella from infected macrophages specifically via induction of autophagy (27–29). The effect of AR-12 on control of Francisella was fully reversed in the presence of the autophagy inhibitor 3-ME or the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine (27). Initially, it was thought that the mechanism of action of AR-12 was the direct inhibition of PDK-I (30), which results in lower AKT phosphorylation, along with endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy induction (24, 26, 31). However, recent studies indicate that PDK-I is not the target of AR-12 (26, 32); rather, the target is immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein (GRP78/BiP). Additionally, our previous studies indicated that AR-12 induces autophagy in macrophages at 1 μM (28, 29), which is much lower than the concentration observed for its inhibitory activity against PDK-1. Thus, although the exact mechanism of autophagy induction has not been resolved, the pathogen clearance mechanism of AR-12 is uniquely at the drug-host instead of drug-pathogen interface, limiting the possibility of cultivating resistant pathogens. Unfortunately, due to toxicity and hydrophobicity concerns, AR-12 is unable to reach therapeutic doses in vivo, which significantly limits its use.

We recently showed that encapsulation of AR-12 in acetalated dextran (Ace-DEX) microparticles (AR-12/MPs) dramatically reduces cytotoxicity while retaining the ability to enhance Salmonella clearance via autophagy in human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) (29). Ace-DEX is derived from Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved dextran and is an acid-sensitive polymer that is stable at neutral pH but will degrade rapidly upon introduction to an acidic environment, such as that in the phagolysosome (33). This is important for treatment of F. tularensis infection because Ace-DEX MPs can passively target phagocytes, and other cell types are unable to engulf particles of that size. Once the particles are internalized, they rapidly release their cargo. In this study, we evaluated the ability of AR-12/MPs to control Francisella infection in hMDMs and in the mouse model of tularemia. Also, we evaluated the in vivo toxicity of intranasally (i.n.) delivered formulations by evaluating histology sections of uninfected and infected lungs. Our studies shed light on the ability of AR-12/MPs to treat tularemia through both needled and needle-free routes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Formulation of AR-12/MPs.

Free base AR-12 was kindly provided by Arno Therapeutics, Inc. Encapsulation of AR-12-encapsulated Ace-DEX microparticles (AR-12/MPs) was performed as described in our previous publication (29). In brief, 1 day prior to particle formation, all glassware was soaked in 1 M sodium hydroxide overnight. The glassware was washed with purified water by use of a Milli-Q Integral water purification system (Billerica, MA) and then dried directly before use. One hundred milligrams of Ace-DEX polymer and 2 mg of AR-12 (2% [wt/wt] loading concentration) were dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM). The DCM-containing polymer and drug were added to 3% (wt/wt) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) to create a stabilized emulsion. The emulsion was then partially submerged in an ice bath and sonicated using a Misonix ultrasonic liquid processor (Farmingdale, NY). Following sonication, the solution was poured into a 0.3% PVA solution in PBS and stirred for 2 h to allow for particles to harden. Following particle hardening, unencapsulated drug was removed using a sterile MidiKros tangential-flow filtration system (Spectrum Labs, Rancho Dominguez, CA). The particles were then collected, frozen, and lyophilized, yielding a white powder. The endotoxin concentration in the particle preparations was shown to be <0.1 endotoxin unit (EU)/ml/mg of MPs.

Size, imaging, and encapsulation efficiency of AR-12/MPs.

Endotoxin-free AR-12/MPs were prepared as previously described (29). Particle size was determined using a model 370 Nicomp submicrometer particle sizer (Santa Barbara, CA). Briefly, particles were suspended in basic water to a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml and were added to the particle sizer. Samples were diluted with basic water until the count rate was acceptable for the instrument. The average diameter was derived from three separate runs. Images of AR-12/MPs were acquired using an FEI Nova NanoSEM 400 microscope. MPs were suspended in basic water to a concentration of 10 mg/ml, and 15 μl was placed on a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) stub and allowed to air dry. The stub was then further processed and imaged to analyze particle morphology. The encapsulation efficiency of AR-12/MPs was defined as the percentage of AR-12 retained within the MPs with respect to the initial drug load. The encapsulation efficiency of AR-12/MPs was determined by preparing a 1-mg/ml solution of AR-12/MPs and blank MPs in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The samples were then read on a plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm and an emission wavelength of 380 nm and compared to a standard curve for free AR-12.

Isolation of hMDMs.

hMDMs were isolated from blood obtained from healthy human donors via venipuncture (34) following a protocol approved by the Ohio State University and University of North Carolina Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was provided by study participants. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized blood over a Ficoll cushion (GE Healthcare Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). PBMCs were then cultured in sterile screw-cap Teflon wells in RPMI 1640 plus l-glutamine (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with 20% autologous human serum at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 for 5 days. PBMCs were then recovered from Teflon wells by chilling the cells on ice, resuspending them in RPMI 1640 with 10% autologous serum, and allowing them to attach in 6-well or 24-well tissue culture plates for 2 to 3 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Lymphocytes were then washed away, leaving hMDM monolayers at a density of approximately 2.0 × 105 cells/well for 24-well plates for F. tularensis SchuS4 infection.

Bacterial cultures and analysis of bacterial growth in hMDMs.

The F. tularensis SchuS4 strain (type A) used in this study was described previously (15). Bacteria were cultured on chocolate II agar plates (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) for 48 h at 37°C prior to use for all experiments. Experiments involving the F. tularensis SchuS4 strain were carried out in The Ohio State University biosafety level 3 (BSL3) select-agent facility in accordance with CDC and locally approved BSL3 facility and safety standards. Analysis of bacterial growth in hMDMs was described previously (27). Briefly, F. tularensis SchuS4 was grown on chocolate II agar plates at 37°C for 48 h. Bacteria were suspended in PBS to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4, equivalent to 3 × 109 CFU/ml. hMDMs were infected with SchuS4 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 in the presence of 2% autologous serum in RPMI 1640 plus l-glutamine (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Two hours after infection, extracellular bacteria were removed by addition of 50 μg/ml of gentamicin (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) to the culture medium for 1 h, and then the cell monolayer was washed thoroughly three times with prewarmed RPMI 1640 to remove unattached bacteria. Infected hMDMs were then treated with different concentrations of free AR-12 or AR-12/MPs, as well as controls, in fresh culture medium containing 2% autologous serum and gentamicin at 10 μg/ml to eliminate potential reinfection by extracellular bacteria. Soluble AR-12 was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in DMSO and diluted to the appropriate concentrations in RPMI 1640 containing 2% autologous serum. At 22 h posttreatment, the infected cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) in PBS for 15 min. The cell lysates were then serially diluted with PBS and spread on chocolate II agar plates. The numbers of surviving intracellular bacteria were determined by enumerating CFU after 72 h of incubation at 37°C.

Mice.

Pathogen-free 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague. Mice were provided food and water ad libitum, divided into groups in sterile microisolator cages, and allowed to acclimatize for 2 to 3 days before challenge. All experimental procedures were carried out in strict accordance with guidelines established by The Ohio State University and University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs), and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Toxicity study of AR-12/MPs in vivo.

To examine the toxicity of AR-12/MPs in mice, mice were administered free AR-12 or AR-12/MPs either intranasally (i.n.) or intraperitoneally (i.p.) for two consecutive days. For i.n. delivery of the drug, mice were anesthetized i.p. with 200 μl tribromoethanol anesthesia (2.5 mg 2,2,2-tribromoethanol, 5 ml 2-methyl-2 butanol, 200 ml water) or 1.5 mg ketamine/kg of body weight in 200 μl PBS and then treated with different doses (1.5, 0.75, and 0.325 mg/kg) of free AR-12 or AR-12/MPs daily for 2 days. Free AR-12 was dissolved in 50 μl of polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400)-0.9% saline-ethanol (50:35:15), while AR-12/MPs were suspended in 50 μl PBS. Mice in the control groups received PBS, PEG-saline-ethanol, or blank MPs equivalent in mass to 1.5 mg/kg AR-12/MPs. For the i.n. delivery of the drug, mice were given 5, 2.5, or 1.25 mg/kg of free AR-12 or AR-12/MPs daily for 2 days in 200 μl of PEG-saline-ethanol or PBS, respectively. Mice in the control groups received PBS or blank MPs equivalent in volume to 200 μl of PEG-saline-ethanol or in mass to 5 mg/kg AR-12/MPs, respectively. The experimental animals were observed daily throughout the course of study for body weight, clinical signs, and mortality. At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed, and lungs were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and subsequently subjected to histopathological examination following hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which was performed by the Comparative Pathology and Mouse Phenotyping Facility of the College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University.

Mouse infection with F. tularensis SchuS4.

F. tularensis SchuS4 was grown on chocolate II agar plates for 48 h at 37°C. The bacteria were collected, suspended in PBS, and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.4, equivalent to 3 × 109 CFU/ml. The desired concentrations of F. tularensis SchuS4 were prepared by serial dilution. Mice were infected with F. tularensis SchuS4 i.n. or i.p., with a lethal dose of 10 CFU per mouse in 50 μl PBS for i.n. infection or in 100 μl PBS for i.p. infection. For i.n. infection and dosing, mice were anesthetized with 200 μl tribromoethanol anesthesia or 1.5 mg/kg ketamine as described above.

Evaluation of protective efficacy of AR-12/MPs in F. tularensis SchuS4-infected BALB/c mice.

To evaluate AR-12 as a treatment for F. tularensis SchuS4 infection, we codelivered AR-12/MPs with a suboptimal daily dose of gentamicin (0.7 mg/kg for i.p. infection and 0.5 mg/kg for i.n. infection), which was determined prior to the experiment (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). After determining the maximum tolerated dose of AR-12/MPs for each route (10 mg/kg i.p. and 3 mg/kg i.n.), we infected mice with F. tularensis SchuS4 and delivered AR-12/MPs through the same needled or needle-free route. The infected mice were given AR-12/MPs two (days 0 and 1) or three (days 0, 1, and 2) times postinfection, and gentamicin was given i.p. daily. The infected mice were monitored for survival for up to 2 weeks postinfection.

Determination of bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens of infected mice.

To examine the effects of AR-12/MP treatment following F. tularensis SchuS4 infection in the mouse model, mice were infected i.n. as described above for the protective efficacy study. A suboptimal dose of gentamicin (0.5 mg/kg for i.n. infection) was given i.p. daily. The infected mice were monitored for survival and/or sacrificed at the indicated time points postinfection. Bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens of infected mice were determined by tissue homogenization and plating for CFU enumeration.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). P values were calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple comparisons and adjusted with Bonferroni's correction. The chi-square test was used for survival analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 or Microsoft Office Excel 2010.

RESULTS

AR-12/MP characteristics.

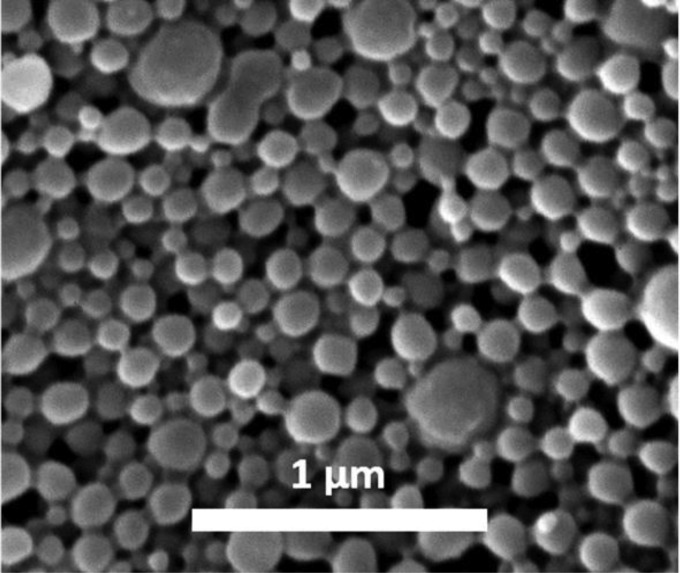

AR-12/MPs were 265 ± 41 nm as determined by use of a submicrometer particle sizer, and the encapsulation efficiency was 36%, yielding an AR-12 final weight load in particles of 0.72% (wt/wt). The spherical morphology of AR-12/MPs was conserved relative to that in our previous work (Fig. 1), and the size of the MPs aligned with our submicrometer particle sizer measurements (29).

FIG 1.

Scanning electron micrograph showing microparticles of acetalated dextran encapsulating AR-12.

AR-12 treatment of F. tularensis SchuS4-infected hMDMs in vitro.

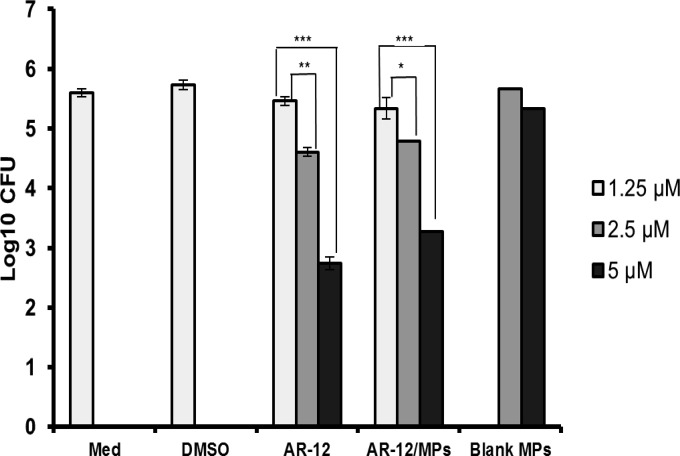

To examine whether AR-12/MPs are capable of inhibiting F. tularensis SchuS4 growth in macrophages, hMDMs were infected with F. tularensis SchuS4 for 2 h, washed, and treated with various concentrations of free AR-12 or AR-12/MPs (1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM) for 22 h. AR-12/MPs inhibited F. tularensis SchuS4 growth in hMDMs in a dose-dependent manner, similarly to free AR-12, resulting in a >2-log decrease in CFU (Fig. 2). Although AR-12/MP treatment did not increase the clearance of F. tularensis SchuS4 in hMDMs compared to that with free drug, AR-12/MPs significantly reduced the cytotoxicity to macrophages compared to that with free drug, allowing for higher concentrations to be used (29).

FIG 2.

Intracellular survival of F. tularensis SchuS4 in hMDMs following AR-12 administration. hMDMs were infected (MOI = 50) for 2 h, washed with gentamicin, and treated with free or encapsulated AR-12. The numbers of intracellular bacterial CFU were determined by plating cell lysates at 22 h postinfection. Negative-control groups included medium alone (Med), blank particles (MPs), and (0.05% [vol/vol]) DMSO (free AR-12 diluent). AR-12, unencapsulated drug; AR-12/MPs, Ace-DEX-encapsulated AR-12; MPs, empty Ace-DEX microparticles. The experiment was repeated three times, and the data from a representative experiment are presented as averages ± standard deviations (SD) (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001).

Evaluation of toxicity in mice following AR-12 administration.

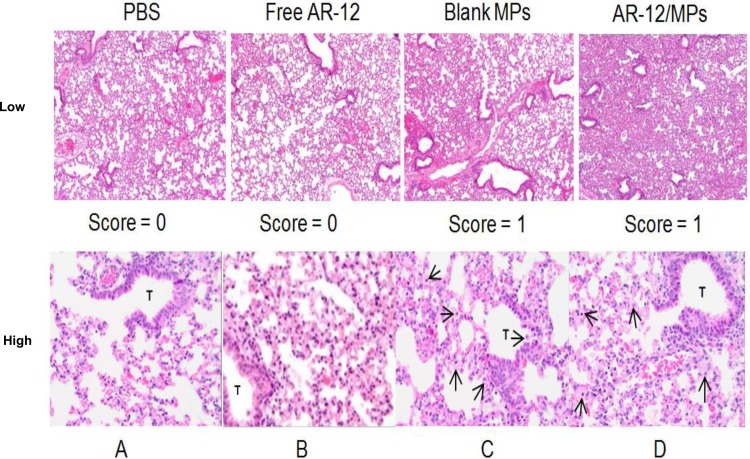

To evaluate the in vivo toxicity of the AR-12 formulations with i.n. delivery, mice were given AR-12/MPs or free AR-12 at 1.5, 0.75, or 0.325 mg/kg daily for 2 days. The control groups were treated with PBS or blank particles (1.5 mg/kg), also given daily for 2 days. The treated mice were monitored for clinical signs of toxicity, and at 10 days posttreatment, lungs were collected and examined for histopathology. Delivery of AR-12/MPs resulted in no adverse clinical signs and only a mild increase in immune cell migration into the lung tissue compared to that in the untreated animals (Fig. 3). Delivery of 1.5 mg or 0.75 mg free AR-12 i.n. resulted in clinical illness shortly after administration of the drug, followed by recovery, which was not observed with AR-12/MPs. For i.p. delivery of the drug, mice were treated daily with AR-12/MPs or free AR-12 at 5, 2.5, or 1.25 mg/kg for 2 days, and no abnormal clinical signs (e.g., sickness or weight loss) were noticed after 10 days posttreatment for any group (data not shown). These results indicate that the i.n. and i.p. routes for delivery of AR-12/MPs are well tolerated in mice at these dosages.

FIG 3.

Lung histology following AR-12 administration. Low (top; ×100)- and high (bottom; ×200)-magnification lung histology sections are shown for mice that received PBS (A), free AR-12 (B), blank MPs (C), or AR-12/MPs (D) via the i.n. route. Immune cell infiltration (macrophages are indicated by arrows) was minimal to mild for blank MPs (C) and mild to moderate for AR-12/MPs (D). Tissue samples were taken 10 days after dosing. For each sample, 1.5 mg/kg was given at days 0 and 1, and for blank MPs, comparable weights of particles were given. T, terminal bronchiole.

AR-12 treatment of F. tularensis SchuS4-infected mice.

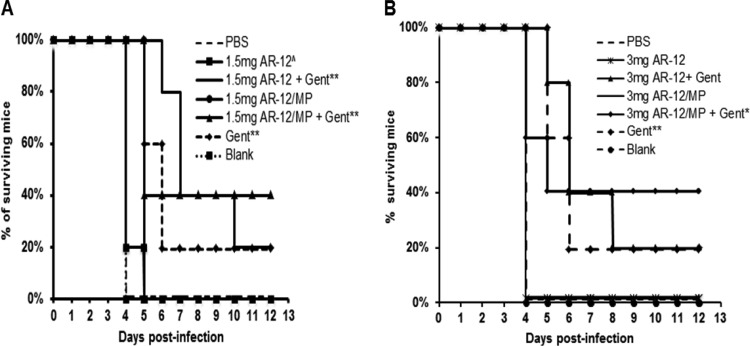

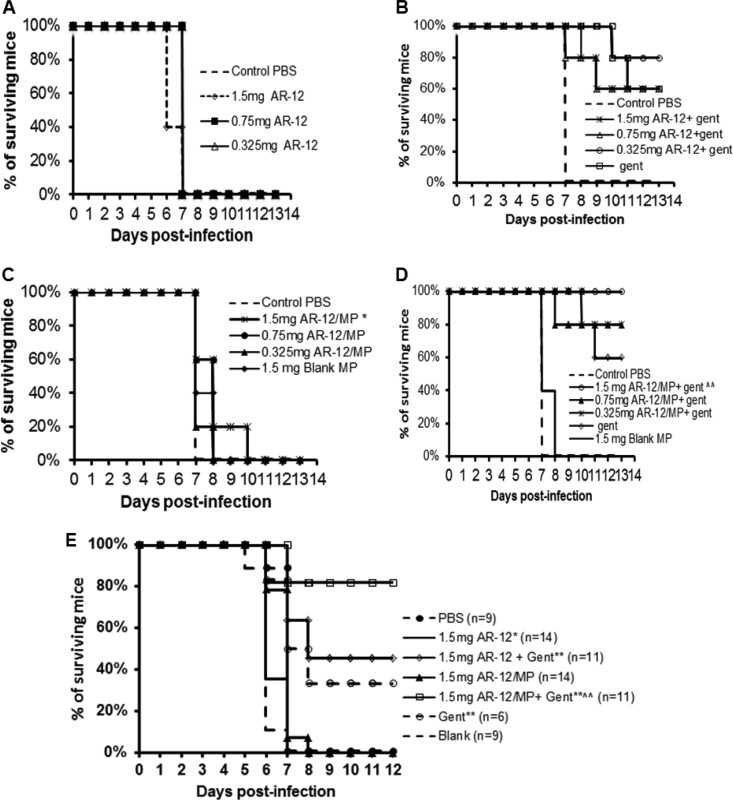

AR-12 or AR-12/MPs were delivered alone or codelivered with a suboptimal daily dose of gentamicin, which was determined previously (0.7 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg given daily for i.p. or i.n. delivery, respectively) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, we examined the effectiveness of delivering AR-12 or AR-12/MPs via the same route (i.p. or i.n.) as that used for the bacterial infection. For all treatment routes, we achieved significantly greater survival with treatment groups than with untreated groups. Infection and treatment (both i.p.) with 1.5 mg/kg (Fig. 4A) or 3 mg/kg (Fig. 4B) of free AR-12 codelivered with daily suboptimal gentamicin increased the survival time compared to that with gentamicin alone, but the improvement was not statistically significant. However, treatment with 1.5 mg/kg (Fig. 4A) or 3 mg/kg (Fig. 4B) of AR-12/MPs codelivered with suboptimal gentamicin resulted in significantly greater protection than that with either gentamicin or AR-12/MPs alone (P ≤ 0.02). AR-12 alone did not show a protective effect in infected mice when both bacteria and AR-12 were delivered by the i.n. route (Fig. 5A). However, codelivery of the lowest concentration of free AR-12 (0.325 mg/kg) with suboptimal gentamicin resulted in greater protection than that with either daily gentamicin or free AR-12 alone (Fig. 5B) (P ≤ 0.02). Importantly, treatment with 1.5 mg/kg of AR-12/MPs alone by the i.n. route increased the survival time by 2 or 3 days compared to that for the free AR-12-, PBS-, or blank particle-treated group (Fig. 5C). When AR-12/MPs were codelivered with daily gentamicin, all encapsulated AR-12 doses significantly protected the mice, with 1.5 mg/kg and suboptimal gentamicin resulting in 100% protection (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 5D).

FIG 4.

Survival curves for BALB/c mice (n = 5) infected i.p. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis SchuS4 following AR-12 treatment. The infected mice were given 1.5 or 3 mg/kg of AR-12 or AR-12/MPs i.p. at days 0 and 1 postinfection, with or without 0.7 mg/kg daily gentamicin i.p. for the length of the experiment. * and **, statistical significance with respect to the PBS control and blank MP-treated groups (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.02); ∧, statistical significance with respect to 1.5 mg AR-12/MPs (P < 0.05).

FIG 5.

Survival curves for BALB/c mice (n = 5) infected i.n. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis SchuS4 following AR-12 treatment. The infected mice were given free AR-12 (A), free AR-12 with gentamicin (Gent) (B), AR-12/MPs (C), or AR-12/MPs with Gent (D). Free AR-12 and AR-12/MPs were given i.n. at 0.325, 0.75, or 1.5 mg/kg on days 0 and 1 postinfection. As indicated, gentamicin was given i.p. daily at 0.5 mg/kg for the length of the study. (E) In a separate experiment, the survival curves for BALB/c mice infected i.n. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis SchuS4 were determined. The infected mice were given 1.5 mg/kg of AR-12/MPs i.n. on days 0 and 1 postinfection. Gentamicin was given daily at 0.5 mg/kg via the i.p. route for the length of the study. * and **, statistical significance with respect to the blank MP control group (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.02).

Because i.n. delivery of 1.5 mg/kg of AR-12/MPs with daily suboptimal gentamicin was 100% protective and significantly more protective than either AR-12/MPs or the antibiotic alone, we increased the number of mice studied at this dose and used similar doses of free and encapsulated AR-12 without gentamicin. This result replicated the significant difference versus the components used individually as treatments but protected at 80%, in contrast to the 100% protection (P ≤ 0.01) that was observed in the previous trial (Fig. 5E).

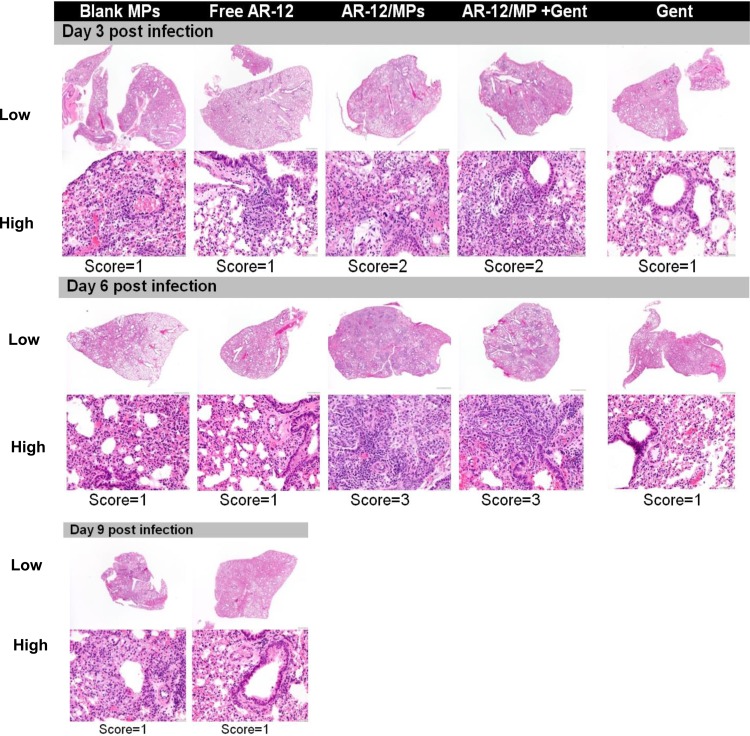

A histopathological study of lung sections from mice from the experiment described for Fig. 5E revealed increased inflammation in the lungs of AR-12/MP-treated mice compared to those of mice treated with blank MPs, free AR-12, or gentamicin alone at both days 3 and 6 postinfection. This was manifested by the presence of perivascular and peribronchiolar cells composed of foamy alveolar macrophages, macrophages, and neutrophils (Fig. 6, lower panel). However, at day 9 postinfection, the condition resolved and there was no difference in the inflammation scores for the lungs from gentamicin- versus AR-12/MP-plus-gentamicin-treated mice (Fig. 5C).

FIG 6.

Histology of lung sections taken from mice infected i.n. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis and then treated with 1.5 mg of AR-12/MPs on days 0 and 1 postinfection, with or without a suboptimal daily dose (0.5 mg/kg) of gentamicin i.p. for the duration of the experiment. Low-magnification (top; ×10) and high-magnification (bottom; ×200) images are provided. Inflammation was scored blindly by a pathologist, according to a tiered, semiquantitative scale adopted from the work of Slight et al. (47), as follows: 0 = no inflammation, 1 = 1% to <25% inflammation, 2 = 25% to <50% inflammation, 3 = 50% to <75% inflammation, and 4 = 75% to 100% inflammation. Blank MPs, empty Ace-DEX microparticles; AR-12/MPs, Ace-DEX MPs encapsulating AR-12; Gent, gentamicin.

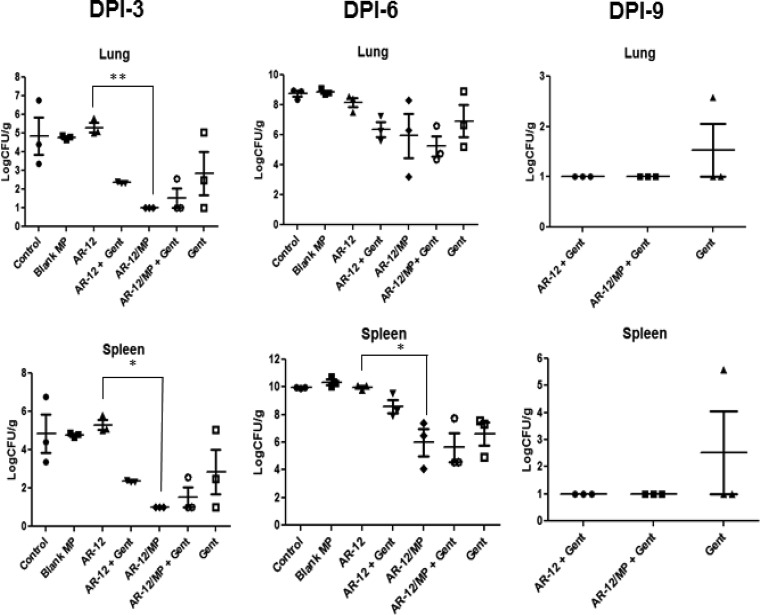

In addition to survival and lung histopathology studies, we evaluated the numbers of CFU in the lungs and spleens of mice at days 3, 6, and 9 postinfection for the experiment described for Fig. 5E. As shown in Fig. 7, there was no significant decrease in the number of CFU recovered at days 3 and 6 postinfection for mice treated with free AR-12 alone versus controls after two administrations of drug. Also, the addition of daily gentamicin to free AR-12 did not result in significant reductions in the number of CFU recovered beyond that observed with gentamicin alone. In contrast, there was a significant reduction in the number of CFU with AR-12/MPs alone versus free AR-12. AR-12/MPs in combination with daily suboptimal gentamicin showed further reductions in CFU compared to the numbers with gentamicin alone, although the results did not reach statistical significance. By day 9 postinfection, the results for free AR-12 and AR-12/MPs in combination with gentamicin were similar, with both reducing the numbers of CFU in organs more than gentamicin alone.

FIG 7.

Bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens of mice (n = 5) infected i.n. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis and then treated i.n. with 1.5 mg/kg of AR-12/MPs on days 0 and 1 postinfection, with or without a suboptimal dose (0.5 mg/kg) of daily gentamicin (Gent) given for the duration of the experiment. Bacterial burdens were examined at 3, 6, and 9 days postinfection (DPI). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. All other comparisons described in Results did not reach these levels of statistical significance.

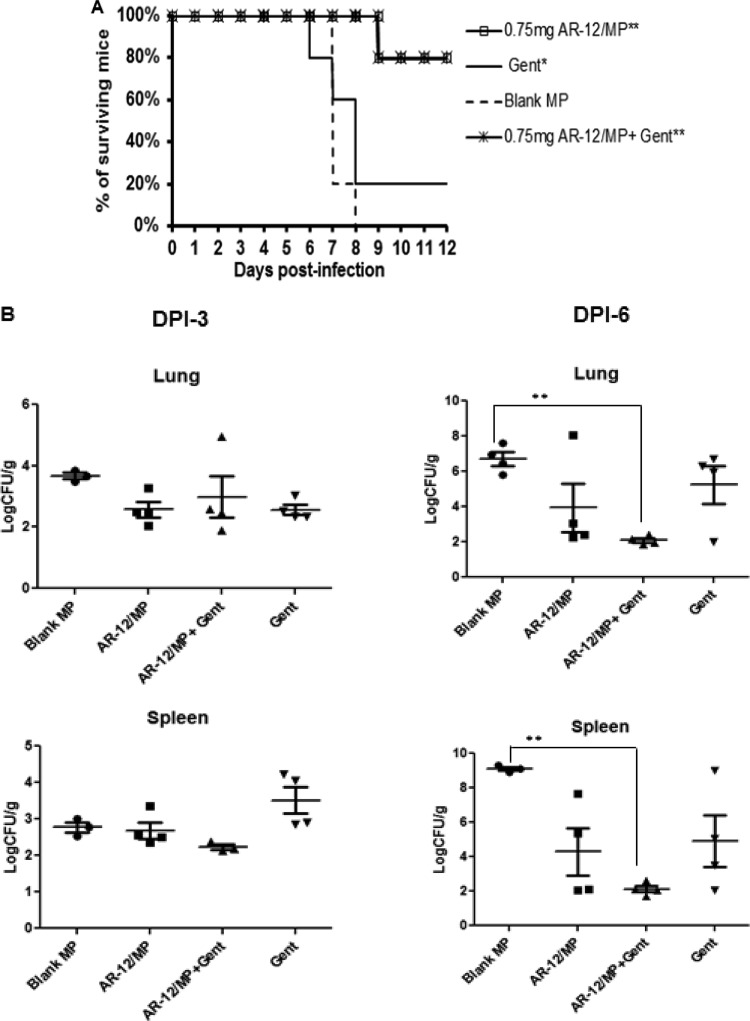

Increased AR-12 dosing of F. tularensis SchuS4-infected mice.

Finally, we sought to determine if increasing the number of doses (from 2 to 3 daily doses) resulted in better protection. Dosing twice (days 0 and 1) with AR-12/MPs alone resulted in 0% survival, whereas an additional dose on day 2 resulted in 80% survival of infected mice, which was significantly better than what was seen with suboptimal gentamicin alone or with blank particles (Fig. 8A). Treatment with AR-12/MPs and gentamicin also resulted in 80% survival, similar to earlier experiments (Fig. 5D). Bacterial burdens were also assessed in the lungs and spleens of these mice at days 3 and 6 postinfection. Although AR-12/MP or gentamicin treatment alone at these time points clearly reduced bacterial burdens in the lungs, neither resulted in a statistically significant difference versus mice treated with blank MPs. However, the combination of AR-12/MPs with gentamicin significantly decreased bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens compared to those in mice treated with AR-12/MPs or gentamicin alone at day 6 postinfection (P ≤ 0.02) (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

(A) Survival curves for BALB/c mice (n = 5) infected i.n. with 10 CFU of F. tularensis. The infected mice were given 0.75 mg/kg of AR-12 in microparticles (AR-12/MPs) i.n. on days 0, 1, and 2 postinfection. As indicated, gentamicin (Gent) was given i.p. daily at 0.5 mg/kg. * and ** indicate statistical significance with respect to the blank MP group (*, P < 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01). (B) Bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens of infected mice (n = 4) examined at 3 and 6 days postinfection (DPI).

DISCUSSION

Infections due to intracellular bacterial pathogens, including F. tularensis, are particularly difficult to treat. Treatment of tularemia in humans is confined to few antibiotics, including aminoglycosides (particularly streptomycin and gentamicin) with known toxicities at therapeutic doses (7, 35). Even with antibiotic treatment, high failure and/or relapse rates (up to 33%) have been reported (35). Resistance of this pathogen to conventional antibiotic therapy has not been reported (8); however, in the context of a biological weapon of terror, antibiotic-resistant strains could be created and pose a significant public health threat. Therefore, there is substantial interest from a public health management perspective in developing new antimicrobial strategies to control this bacterial pathogen (7).

AR-12 has previously been used to enhance the clearance of several intracellular pathogens; however, its hydrophobicity and toxicity limit the in vivo therapeutic efficacy. To overcome the hydrophobic/toxic drawbacks and also to passively target infected macrophages, we encapsulated AR-12 in the acid-sensitive polymer Ace-DEX. The AR-12/MPs used in this study showed an encapsulation efficiency similar to that in our previous work (29) and were shown to be 265 nm in diameter (Fig. 1), which is an ideal size for uptake via macrophages but not by nonphagocytic cells (36–38). Particle formulation through sonication generates a polydispersed particle population; however, Champion et al. noted that the main determinant for uptake by macrophages is shape, and thus, polydispersed particle populations of the same shape that lie within the optimal uptake range for macrophages should be taken up at similar rates (38). Additionally, particles of this size are not optimal targets for dendritic cells and will not be trafficked away from the site of administration as readily, allowing for persistent passive targeting of macrophages (39). The potential for sustained passive treatment at the site of administration is important for an intracellular bacterium such as F. tularensis, which uses various strategies to avoid recognition by the host and allow for its replication and dissemination (14, 15, 19).

In the current study, we observed a dose-dependent inhibitory effect of AR-12/MPs on the growth of F. tularensis in hMDMs that was comparable to that of free drug (Fig. 2), which occurs at concentrations of drug that do not directly kill F. tularensis in vitro (27). However, in our previous work with AR-12/MPs, we demonstrated that encapsulation allowed for higher drug concentrations to be used, as the MPs alleviated the in vitro toxicity observed with free drug at concentrations of >5 μM (29). Our collective data provide further evidence for the effectiveness of AR-12/MPs in controlling intracellular bacterial pathogens that reside in macrophages. In fact, the increasing evidence for AR-12's effectiveness in controlling intracellular pathogens, such as Francisella and Salmonella (40, 41), indicates the potential of AR-12 as a broad-spectrum, host-directed anti-infective agent.

We examined the toxicity of AR-12/MPs by using a mouse model. Lung histopathological studies of i.n. AR-12/MP-treated mice (uninfected) showed a small increase in infiltration of immune cells compared to that in PBS-treated control mice (Fig. 3). AR-12 and AR-12/MPs administered i.n. to infected mice showed an inflammation score of 3 at 6 days postinfection (Fig. 7). This score indicates that there is a greater inflammatory response when AR-12 is administered to an infected mouse than an uninfected mouse and highlights the potential benefit of using AR-12 in a manner similar to that for many adjunctive immunomodulatory compounds. However, in contrast to several of these compounds, such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists (42), AR-12/MPs do not appear to have significant toxicities, even when the host is not infected. A more comprehensive evaluation of the potential adverse effects of the drug in vivo is planned for future experiments.

AR-12/MPs appeared to work as efficiently in vitro as free AR-12 at concentrations below those of free AR-12 that cause toxicity, consistent with our previous work (29). In vitro, the benefits of encapsulation, i.e., enhanced macrophage targeting and elimination of free compound hydrophobicity, are not as prominent. Additionally, at the concentrations used, we were likely saturating the ability to induce autophagy regardless of the encapsulation status. However, we demonstrated here that passive macrophage targeting and hydrophobicity mitigation allowed for AR-12/MPs to be superior to free AR-12 when delivered via the same route of infection in vivo (Fig. 4 and 5). Regardless of the route of infection, F. tularensis primarily enters phagocytic cells, which facilitates systemic dissemination of the pathogen throughout the body, including the lungs, liver, and spleen. When AR-12/MPs were given through the same route as that used for infection, it is likely that the AR-12/MPs were efficiently taken up by both infected and noninfected phagocytic cells, resulting in higher local intracellular concentrations than those of the free drug. In addition, the AR-12/MP-containing noninfected cells would be expected to be more resistant to phagocytosed Francisella. Interestingly, we observed that i.n. delivery of AR-12/MPs to treat i.n. infected mice resulted in stronger effects than those for i.p. AR-12/MP delivery to treat i.p. infected mice (Fig. 4 and 5). This may reflect higher local concentrations of AR-12 as a result of delivery to a more confined compartment in the lung. Additionally, the respiratory tract is a major portal of entry for pneumonic tularemia, from which dissemination occurs (1). The delivery of F. tularensis as a bioweapon by this route is particularly dangerous due to the ease of infectivity and the high fatality rate from infection (1). In the case of a bioterrorism attack, needle-free routes are preferred, since they allow for enhanced patient compliance, decreased injection site pain, reduced costs, and administration of the anti-infective at the site of action (43). Due to all of these factors, i.n. delivery of AR-12/MPs would be beneficial during a bioterror threat.

Use of i.n. delivery of AR-12/MPs at days 0 and 1 to treat i.n. infection with F. tularensis resulted in a prolonged survival time (Fig. 5) and better control of bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleen (Fig. 7). AR-12/MPs alone could even protect the infected mice from death when the treatment was extended to 3 days (days 0, 1, and 2 postinfection) (Fig. 8A). This was possibly due to the observed increase in inflammation at 3 to 6 days postinfection, whereby phagocytic cells were shown to be recruited to the lungs of AR-12/MP-treated mice (Fig. 3 and 6). This inflammation, together with autophagy induced by AR-12/MPs, may overcome early immune suppression by F. tularensis in the lungs (15, 44), enhancing control of the pathogen by the host. Indeed, the CFU data together with the lung histopathology data indicate that inflammation induced by AR-12/MPs helps infected mice to control the bacterial burden in the lungs.

When AR-12 and AR-12/MPs were delivered in combination with suboptimal gentamicin treatment, mice infected with F. tularensis had prolonged survival over that with either drug alone (Fig. 4, 5, and 7). Additionally, using an increased duration of dosing with AR-12/MPs and suboptimal gentamicin led to decreased bacterial burdens with respect to all other groups. Combination therapeutic strategies consisting of host-directed agents and traditional antibiotics are an emerging approach to control intracellular bacterial infections (45). This approach may lead not only to increased effectiveness of antibiotics but also to reduced antibiotic usage and reduced development of resistant strains. In fact, i.n. delivery of interleukin-12 (IL-12) in combination with antibiotics has shown efficacy in the control of F. tularensis infection in a mouse model (13). Directly related to our study, Lo et al. (46) showed that AR-12 could be used to sensitize the intracellular bacterial pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to traditional antibiotics both in vitro and in vivo, highlighting the possible use of AR-12 as a host-directed therapy.

In this study, we showed that the host-directed therapeutic AR-12 encapsulated in Ace-DEX microparticles has the ability to control F. tularensis in vitro and in vivo. In addition to having lower toxicity, the encapsulated form of AR-12 showed greater efficacy in vivo than did free AR-12. When the dosing regimen was expanded to 3 days, survival of mice infected with F. tularensis was enhanced, and codelivery of AR-12 with a suboptimal dose of gentamicin enhanced the protective effects in a mouse model of tularemia over those with either drug alone by reducing bacterial loads in the lungs and spleen. Thus, combination therapy using a host-directed agent can aid in pathogen clearance and is a promising future direction of research. Taken together, the data in our study provide support for the potential use of Ace-DEX-encapsulated AR-12 for the treatment of pneumonic tularemia.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Department of Veterinary Biosciences at The Ohio State University for the evaluation of lung histopathology.

This research was supported by NIH grants R21AI102252 and R33AI102252.

We have received sponsored research funding from Arno Therapeutics for work outside that contained in this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02228-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oyston PC, Sjostedt A, Titball RW. 2004. Tularaemia: bioterrorism defence renews interest in Francisella tularensis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:967–978. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Prior JA, Wilson HE, Carhart S. 1961. Tularemia vaccine study. II. Respiratory challenge. Arch Intern Med 107:702–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis DT, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Friedlander AM, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge SR, McDade JE, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Tonat K, Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. 2001. Tularemia as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 285:2763–2773. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitadze N, Kuchuloria T, Clark DV, Tsertsvadze E, Chokheli M, Tsertsvadze N, Trapaidze N, Lane A, Bakanidze L, Tsanava S, Hepburn MJ, Imnadze P. 2009. Water-borne outbreak of oropharyngeal and glandular tularemia in Georgia: investigation and follow-up. Infection 37:514–521. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-8193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauri AM, Hofstetter I, Seibold E, Kaysser P, Eckert J, Neubauer H, Splettstoesser WD. 2010. Investigating an airborne tularemia outbreak, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 16:238–243. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.081727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Wilson HE, Prior JA, Carhart S. 1961. Tularemia vaccine study. I. Intracutaneous challenge. Arch Intern Med 107:689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boisset S, Caspar Y, Sutera V, Maurin M. 2014. New therapeutic approaches for treatment of tularaemia: a review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:40. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urich SK, Petersen JM. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of isolates of Francisella tularensis types A and B from North America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2276–2278. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01584-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutera V, Levert M, Burmeister WP, Schneider D, Maurin M. 2014. Evolution toward high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Francisella species. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:101–110. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Origgi FC, Frey J, Pilo P. 2014. Characterisation of a new group of Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica in Switzerland with altered antimicrobial susceptibilities, 1996 to 2013. Euro Surveill 19:20858. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.29.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Castrillon JL, Bachiller-Luque P, Martin-Luquero M, Mena-Martin FJ, Herreros V. 2001. Tularemia epidemic in northwestern Spain: clinical description and therapeutic response. Clin Infect Dis 33:573–576. doi: 10.1086/322601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosker M, Sener D, Kilic O, Akil F, Yilmaz M, Ozturk O, Cokugras H, Camcioglu Y, Akcakaya N. 2013. A case of oculoglandular tularemia resistant to medical treatment. Scand J Infect Dis 45:725–727. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.796089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pammit MA, Budhavarapu VN, Raulie EK, Klose KE, Teale JM, Arulanandam BP. 2004. Intranasal interleukin-12 treatment promotes antimicrobial clearance and survival in pulmonary Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4513–4519. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4513-4519.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones CL, Napier BA, Sampson TR, Llewellyn AC, Schroeder MR, Weiss DS. 2012. Subversion of host recognition and defense systems by Francisella spp. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:383–404. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05027-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai S, Rajaram MV, Curry HM, Leander R, Schlesinger LS. 2013. Fine tuning inflammation at the front door: macrophage complement receptor 3-mediates phagocytosis and immune suppression for Francisella tularensis. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003114. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsa KVL, Butchar JP, Rajaram MVS, Cremer TJ, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS, Tridandapani S. 2008. Francisella gains a survival advantage within mononuclear phagocytes by suppressing the host IFN gamma response. Mol Immunol 45:3428–3437. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. 2004. Virulent and avirulent strains of Francisella tularensis prevent acidification and maturation of their phagosomes and escape into the cytoplasm in human macrophages. Infect Immun 72:3204–3217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3204-3217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santic M, Asare R, Skrobonja I, Jones S, Abu Kwaik Y. 2008. Acquisition of the vacuolar ATPase proton pump and phagosome acidification are essential for escape of Francisella tularensis into the macrophage cytosol. Infect Immun 76:2671–2677. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00185-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohapatra NP, Balagopal A, Soni S, Schlesinger LS, Gunn JS. 2007. AcpA is a Francisella acid phosphatase that affects intramacrophage survival and virulence. Infect Immun 75:390–396. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01226-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Checroun C, Wehrly TD, Fischer ER, Hayes SF, Celli J. 2006. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:14578–14583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santic M, Akimana C, Asare R, Kouokam JC, Atay S, Kwaik YA. 2009. Intracellular fate of Francisella tularensis within arthropod-derived cells. Environ Microbiol 11:1473–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele S, Brunton J, Ziehr B, Taft-Benz S, Moorman N, Kawula T. 2013. Francisella tularensis harvests nutrients derived via ATG5-independent autophagy to support intracellular growth. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003562. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong A, Wehrly TD, Child R, Hansen B, Hwang S, Virgin HW, Celli J. 2012. Cytosolic clearance of replication-deficient mutants reveals Francisella tularensis interactions with the autophagic pathway. Autophagy 8:1342–1356. doi: 10.4161/auto.20808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao M, Yeh PY, Lu YS, Hsu CH, Chen KF, Lee WC, Feng WC, Chen CS, Kuo ML, Cheng AL. 2008. OSU-03012, a novel celecoxib derivative, induces reactive oxygen species-related autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 68:9348–9357. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucab JE, Lee C, Chen CS, Zhu J, Gilks CB, Cheang M, Huntsman D, Yorida E, Emerman J, Pollak M, Dunn SE. 2005. Celecoxib analogues disrupt Akt signaling, which is commonly activated in primary breast tumours. Breast Cancer Res 7:R796–R807. doi: 10.1186/bcr1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park MA, Yacoub A, Rahmani M, Zhang G, Hart L, Hagan MP, Calderwood SK, Sherman MY, Koumenis C, Spiegel S, Chen CS, Graf M, Curiel DT, Fisher PB, Grant S, Dent P. 2008. OSU-03012 stimulates PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum-dependent increases in 70-kDa heat shock protein expression, attenuating its lethal actions in transformed cells. Mol Pharmacol 73:1168–1184. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiu HC, Soni S, Kulp SK, Curry H, Wang D, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS, Chen CS. 2009. Eradication of intracellular Francisella tularensis in THP-1 human macrophages with a novel autophagy inducing agent. J Biomed Sci 16:110. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu HC, Kulp SK, Soni S, Wang D, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS, Chen CS. 2009. Eradication of intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with a small-molecule, host cell-directed agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5236–5244. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00555-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoang KV, Borteh HM, Rajaram MV, Peine KJ, Curry H, Collier MA, Homsy ML, Bachelder EM, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS, Ainslie KM. 2014. Acetalated dextran encapsulated AR-12 as a host-directed therapy to control Salmonella infection. Int J Pharm 477:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J, Huang JW, Tseng PH, Yang YT, Fowble J, Shiau CW, Shaw YJ, Kulp SK, Chen CS. 2004. From the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib to a novel class of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 inhibitors. Cancer Res 64:4309–4318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YC, Kulp SK, Wang D, Yang CC, Sargeant AM, Hung JH, Kashida Y, Yamaguchi M, Chang GD, Chen CS. 2008. Targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress and Akt with OSU-03012 and gefitinib or erlotinib to overcome resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Cancer Res 68:2820–2830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth L, Cazanave SC, Hamed HA, Yacoub A, Ogretmen B, Chen CS, Grant S, Dent P. 2012. OSU-03012 suppresses GRP78/BiP expression that causes PERK-dependent increases in tumor cell killing. Cancer Biol Ther 13:224–236. doi: 10.4161/cbt.13.4.18877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kauffman KJ, Do C, Sharma S, Gallovic MD, Bachelder EM, Ainslie KM. 2012. Synthesis and characterization of acetalated dextran polymer and microparticles with ethanol as a degradation product. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 4:4149–4155. doi: 10.1021/am3008888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlesinger LS, Bellingerkawahara CG, Payne NR, Horwitz MA. 1990. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component-C3. J Immunol 144:2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enderlin G, Morales L, Jacobs RF, Cross JT. 1994. Streptomycin and alternative agents for the treatment of tularemia: review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 19:42–47. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirota K, Hasegawa T, Hinata H, Ito F, Inagawa H, Kochi C, Soma G, Makino K, Terada H. 2007. Optimum conditions for efficient phagocytosis of rifampicin-loaded PLGA microspheres by alveolar macrophages. J Control Release 119:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. 2004. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem J 377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/bj20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Champion JA, Katare YK, Mitragotri S. 2007. Particle shape: a new design parameter for micro- and nanoscale drug delivery carriers. J Control Release 121:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manolova V, Flace A, Bauer M, Schwarz K, Saudan P, Bachmann MF. 2008. Nanoparticles target distinct dendritic cell populations according to their size. Eur J Immunol 38:1404–1413. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr EL, McMullan LK, Lo MK, Spengler JR, Bergeron E, Albarino CG, Shrivastava-Ranjan P, Chiang CF, Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF, Flint M. 2015. Inhibitors of cellular kinases with broad-spectrum antiviral activity for hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antiviral Res 120:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chabrier-Rosello Y, Gerik KJ, Koselny K, DiDone L, Lodge JK, Krysan DJ. 2013. Cryptococcus neoformans phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) ortholog is required for stress tolerance and survival in murine phagocytes. Eukaryot Cell 12:12–22. doi: 10.1128/EC.00235-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engel AL, Holt GE, Lu H. 2011. The pharmacokinetics of Toll-like receptor agonists and the impact on the immune system. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 4:275–289. doi: 10.1586/ecp.11.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giudice EL, Campbell JD. 2006. Needle-free vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 58:68–89. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosio CM, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Belisle JT. 2007. Active suppression of the pulmonary immune response by Francisella tularensis Schu4. J Immunol 178:4538–4547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spellberg B, Bartlett JG, Gilbert DN. 2013. The future of antibiotics and resistance. N Engl J Med 368:299–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo JH, Kulp SK, Chen CS, Chiu HC. 2014. Sensitization of intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to aminoglycosides in vitro and in vivo by a host-targeted antimicrobial agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7375–7382. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03778-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slight SR, Monin L, Gopal R, Avery L, Davis M, Cleveland H, Oury TD, Rangel-Moreno J, Khader SA. 2013. IL-10 restrains IL-17 to limit lung pathology characteristics following pulmonary infection with Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Am J Pathol 183:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.