Abstract

The discovery of new antimalarial drugs able to target both the asexual and gametocyte stages of Plasmodium falciparum is critical to the success of the malaria eradication campaign. We have developed and validated a robust, rapid, and cost-effective high-throughput reporter gene assay to identify compounds active against late-stage (stage IV and V) gametocytes. The assay, which is suitable for testing compound activity at incubation times up to 72 h, demonstrates excellent quality and reproducibility, with average Z′ values of 0.85 ± 0.01. We used the assay to screen more than 10,000 compounds from three chemically diverse libraries. The screening outcomes highlighted the opportunity to use collections of compounds with known activity against the asexual stages of the parasites as a starting point for gametocytocidal activity detection in order to maximize the chances of identifying gametocytocidal compounds. This assay extends the capabilities of our previously reported luciferase assay, which tested compounds against early-stage gametocytes, and opens possibilities to profile the activities of gametocytocidal compounds over the entire course of gametocytogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

The complex life cycle of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, responsible for malaria, involves a human host, in which the intraerythrocytic asexual stages of the parasite cause the disease manifestations, and an anopheline mosquito vector, in which the parasite transmission stages genetically recombine and develop to successfully infect new human hosts. Parasite transmission to both the mosquito vector and the next human host rely on the sexual stage gametocytes. In P. falciparum, gametocytes emerge in low numbers from the asexual population and mature over a 10- to 12-day period, progressing through five morphologically distinct stages (I to V) (1). Mature stage V gametocytes can remain infective to the mosquito for an extended time, even if the asexual parasite population has been decreased by therapeutic drugs (2).

The last 15 years have witnessed an unprecedented effort in the fight against malaria, with the deployment of large-scale interventions, including the distribution of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs); targeted chemoprophylaxis of patient populations at particular risk, notably pregnant women and children under the age of 5 years; and vector control measures, including insecticide-treated bed nets. As a result, a 48% decrease in global malaria mortality rates was achieved between 2000 and 2015, and 16 countries have successfully eliminated malaria since 2010 (3). Although these impressive achievements have required a substantial economic outlay, it has become increasingly clear that an aggressive strategy aimed at malaria eradication is the only sustainable, albeit ambitious, goal in the long term (4). Achieving this ultimate goal is challenging, as malaria claims nearly 440,000 lives annually, and nearly half of the world's population is at risk of contracting the disease (3). The emergence of parasites resistant to current therapeutics (5–7) and mosquito vectors impervious to insecticides (8) causes considerable concern for the sustained progress of the strategy (9).

The need to develop new drugs is compelling and is compounded by the necessity to target multiple stages of a complex life cycle to attain the goal of eradication (10). Recent efforts in high-throughput screening (HTS) have identified novel chemical classes, some of which are able to target multiple parasite stages and have now progressed to clinical trials (11, 12). Because gametocytes directly precede transmission to the vector, these forms have been identified as a key life cycle stage to target. Transmission-blocking activity has been deemed necessary for all new drug combinations under development (13); however, it has proved difficult to identify compounds active against both the asexual and gametocyte stages of the P. falciparum life cycle, since gametocytes have been shown to become less sensitive to many drugs targeting asexual parasites as their maturation progresses (14–16). Therefore, it is necessary to develop new screening approaches that allow the identification of gametocytocidal compounds, with an emphasis on compounds targeting the later stages of development.

Gametocytocidal assays with high throughput capability (i.e., utilizing 384- or 1,536-well plates) for late-stage and mature (stage III to V) P. falciparum gametocytes utilizing fluorescent indicators of metabolic activity (17, 18), fluorescence imaging (19–21), or chemiluminescence (18) have been previously described. We have recently developed and validated an HTS assay for early-stage (stage I to III) P. falciparum gametocytes (15). With the present work, we have extended this approach to provide a rapid, straightforward, and cost-effective HTS assay capable of assessing compound activity against late-stage gametocytes, with the additional benefit of profiling activity throughout the process of gametocyte development and maturation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite culturing and gametocyte production.

Assay development was performed with the P. falciparum NF54Pfs16 reporter gene line, which expresses a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-luciferase fusion under the temporal control of the gametocyte-specific Pfs16 promoter (22).

Asexual parasites were cultured as previously described (23), with some modifications: the parasites were maintained in human type O positive red blood cells (RBCs) at 5% hematocrit (hct) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES (Sigma), 50 μg/ml hypoxanthine, 5% AB human serum (Sigma), and 2.5 mg/ml Albumax II (Gibco). Parasite cultures were maintained at <2% parasitemia at all times and incubated under standard conditions (37°C in a standard gas mixture of 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2).

Gametocyte production was carried out using our established protocol (19), with minor modifications. Sorbitol-synchronized cultures at the trophozoite stage were isolated using a CS magnetic column (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec) on day −3 of the sexual induction protocol. Fresh RBCs were added to the isolated trophozoites to achieve 2% parasitemia and 1.25% hct. After overnight shaking, the day −2 cultures were allowed to reach 10% parasitemia and then exposed to nutritional stress (1:4 spent medium) at 2.5% hct overnight. Parasitemia levels of the resulting cultures on day −1 were reduced to 2%, and the cultures were gently agitated overnight. The following day (day 0 of gametocytogenesis), the cultures were magnetically purified, parasitemia was adjusted to 10% rings in all cultures, and 50 mM N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the medium to clear residual asexual parasites. Two-thirds of the medium was then changed with NAG-supplemented medium every day until day 8. On day 8 of gametocytogenesis, a final magnetic purification of the gametocyte cultures was performed before use to concentrate the gametocytes to the final gametocytemia to be used in the assay.

Late-stage assay conditions.

For all the luminescence readouts, we used the homogeneous luciferase reporter gene assay system Steadylite Plus (PerkinElmer). A previously validated protocol was employed to lyse the cultures, and luciferase substrate was added (15). First, 25 μl medium was aspirated from the assay plates and replaced with 15 μl Steadylite, without disturbing the settled RBCs, using a Biomek FX high-throughput liquid-handling system (Beckman Coulter). Luminescence was measured after the relevant incubation time at room temperature using a MicroBeta Trilux multidetector luminometer equipped with a plate stacker for high-throughput applications.

The effect of the percent gametocytemia and the percent hct on the luciferase signal was assessed in 384-well white luminescence plates (Culturplate; PerkinElmer) after 72 h of incubation under standard conditions. Sixteen replicate wells were seeded with day 8 gametocytes at a range of hct percentages (0.1, 0.25, and 0.5%) and gametocytemia percentages (1.5, 3, 6, and 12%). After the incubation, the luciferase signal was read in the plates at regular intervals from 1 h to 6 h 45 min after the addition of Steadylite.

The consistency of the gametocytocidal compound potency data generated by the assay was tested by measuring the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of puromycin at multiple time points after the addition of the luciferase kit. The Z′, a measure of assay quality and reproducibility for predicting suitability for screening, was determined based on 0.4% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 5 μM puromycin as negative and positive controls, respectively (24).

Assay validation.

The late-stage gametocyte luciferase assay was validated by testing a panel of 39 antimalarial drugs and clinical candidates. The compounds were tested in a dose-response assay with a starting concentration of 10 μM diluted in 16 serial dilution steps, with three concentrations per log dose. DMSO (0.4%, corresponding to the final DMSO concentration in all compound-treated wells) and puromycin (5 μM) were used as in-plate negative and positive controls, respectively. The experiment was carried out in two independent biological replicates, with two technical replicates for each concentration.

Screening of chemical libraries against late-stage gametocytes.

The MMV Malaria Box is a collection of diverse chemical compounds with proven antiplasmodial activity (25). The collection was kindly provided by Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) as 10 mM stocks in 100% DMSO. The library, received as a set of five 96-well plates containing a total of 390 compounds, was reformatted into two 384-well plates after 2-fold dilution using 100% DMSO. The 5 mM DMSO stocks were stored at −20°C. For the assay setup, the 5 mM stocks were further diluted 4-fold into DMSO to give 1.25 mM stocks which were diluted 25-fold in water and then 10-fold in the final assay plate to obtain a final screening concentration of 5 μM and 0.4% DMSO. The MMV Malaria Box was screened at a single dose of 5 μM. Hits were manually cherry picked from fresh stocks, serially diluted, and tested in dose-response assays as described above (14 points; range, 0.25 nM to 5 μM) in three biological replicates. Three Malaria Box compounds, MMV006172, MMV019918, and MMV667491, were also tested in the same concentration range on gametocytes that were allowed to reach mature stage V on day 12 of gametocytogenesis. Luciferase readout was performed on day 15 in this case.

The ERS_01 library consisted of 4,760 commercially available, structurally diverse compounds and was compiled as an independent compound set within the Avery laboratory. The compounds were obtained as 1 mM stocks in 100% DMSO and were diluted to a final screening concentration of 4 μM. Active compounds were cherry picked from stock plates and retested in 4 doses (0.10, 0.40, 1, and 4 μM) in two technical replicates.

The GDB_04 library is a collection of 4,900 compounds belonging to 1,225 diverse scaffolds, with 4 representative compounds for each scaffold. The library was obtained from Compounds Australia as 1-μl 5 mM stocks in 100% DMSO from a larger collection. The compounds were diluted to a final screening concentration of 10 μM. Active compounds were retested in 10-point dose-response assays (concentration range, 5 nM to 20 μM; two technical replicates) alongside a variable number (1 to 28) of analogues for each scaffold. In all of the above-described experiments, the assay plates were read starting 1 h after the addition of Steadylite.

Assessment of compound action throughout whole gametocytogenesis.

Gametocytes were exposed to chloroquine, mefloquine, artesunate, and puromycin in a 16-point dose-response gradient (concentration range, 0.4 nM to 40 μM) for 72 h every 2 days starting from day 0 of gametocytogenesis, at the end of which Steadylite was added to the plates and the luciferase signal was read after 1 h. A total of six time spans were examined: days 0 to 3, days 2 to 5, days 4 to 7, days 6 to 9, days 8 to 11, and days 10 to 13. For the time points through day 6, the assay was set up as previously described (15); for the day 8 time point onward, gametocyte cultures were magnetically purified on day 8, and a late-stage assay was set up at each time point as described above.

Data analysis.

Raw luminescence data were normalized by detector efficiency and by the signal window determined from the in-plate positive (5 μM puromycin) and negative (0.4% DMSO) controls. Percent inhibition was calculated using the following formula: percent inhibition = 100 − [(sample − positive control)/(negative control − positive control)] × 100.

Inhibition data from screening were analyzed in Microsoft Office Excel 2013 to identify hits and calculate assay statistics (hit rate, percent coefficient of variation [CV], signal-to-noise ratio [S/N], and Z′). Inhibition data from dose-response experiments were fitted by 4-parameter nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism version 5.0 to obtain IC50s.

RESULTS

Late-stage luciferase gametocytocidal assay parameters.

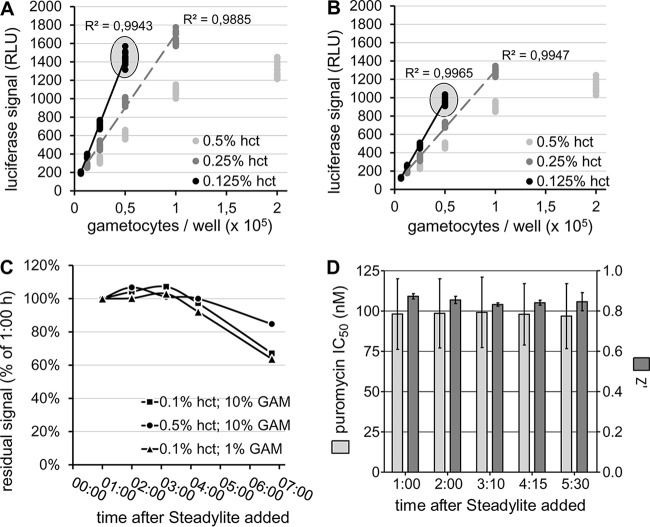

The luciferase signal obtained from day 11 (stage V) P. falciparum gametocytes after 72 h of incubation in assay plates showed a clear relationship with the number of gametocytes originally seeded in the plates (Fig. 1A and B). One hour after the addition of Steadylite, a linear relationship was observed between gametocyte numbers up to 100,000/well and the luciferase signal at all hematocrit levels tested. At 0.5% hct, saturation in the luciferase readout was observed at a higher number of gametocytes per well. An increasingly strong correlation, as well as a higher luminescence signal at similar gametocyte numbers, was obtained as hct values decreased. This was likely because a reduced hct (i.e., reducing the number of uninfected RBCs in the sample) reduced the effect of luminescence quenching by the hemoglobin contained in the uninfected RBCs (26). At 0.1% hct, the average ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 16 wells) luminescence signal from a 10% gametocyte culture was 1,441.9 ± 15.6 relative light units (RLU) (Fig. 1A) compared to 25.79 ± 0.39 RLU of a 5 μM puromycin-treated culture (positive control; n = 16 wells) and 0.29 ± 0.04 RLU of a 0.1% hct uninfected RBC culture (background; n = 9 wells). When the assays were read after more than a 6-h incubation with the luciferase detection reagents, the pattern and strength of the gametocyte number/luciferase signal correlation remained unaltered (Fig. 1B) (R2 [6 h] = 0.9965 compared to R2 [1 h] = 0.9943 at 0.1% hct). Over such a long incubation time, the absolute luciferase intensity value decreased to just above 60% of the 1-h signal at 0.1% hct. The decay did not appear to be dependent on the gametocyte numbers in the plate wells (Fig. 1C), with samples at 1% and 10% gametocytemia showing similar residual signals after 6 h 45 min.

FIG 1.

Optimization of P. falciparum late-stage gametocytocidal luciferase assay. (A and B) Effects of gametocyte numbers per well (range, 6,300 to 200,000) on the resulting luciferase signal intensity 1 h (A) and 6 h 45 min (B) after Steadylite addition to the 384-microwell plates. The conditions used for the final screening assay (10% gametocytemia and 0.1% hematocrit) are circled. (C) Residual luciferase signal under various culture conditions, expressed as a percentage of each respective 1-hour signal. GAM, gametocytes. (D) Consistency of the assay's Z′ and measurement of puromycin IC50 at each time point between 1 h and 6 h 45 min after the addition of the Steadylite kit. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Under the chosen optimized conditions for the assay, namely, 0.1% hct and 10% gametocytemia in a 50-μl/well final volume, corresponding to ∼34,000 gametocytes per well, the assay Z′ remained above 0.8 at all the assessed time points. Optimal consistency was obtained in the determination of the puromycin IC50 throughout, ranging between 96.8 and 99.2 nM (average ± SEM = 98.1 ± 0.4 nM) (Fig. 1D).

Assay validation.

Using our luciferase assay, a set of 39 antimalarial compounds and drugs belonging to 11 different chemical classes with known activity against P. falciparum sexual stages were tested (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Our findings are described below.

(i) Endoperoxides.

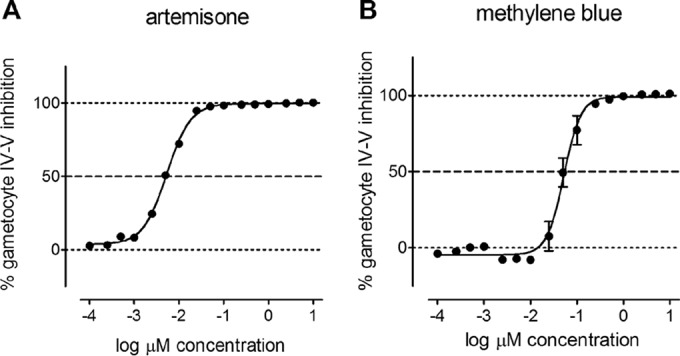

Members of the endoperoxide class of antimalarial compounds form the central pillar of ACTs, the currently recommended first-line antimalarials. Artemisinin and its derivatives possess potent in vitro asexual- and early gametocyte stage inhibition (15) and have been found to inhibit later stages of gametocyte development in vitro (19), as well as mature male and female gametocytes (18, 27). In our luciferase assay, all the representatives of this class tested showed potent inhibition of late-stage gametocytes, with IC50s in the nanomolar range (5 to 91 nM) (Fig. 2A; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Late-stage gametocytocidal activity of the most potent endoperoxide, artemisone, and the most potent nonendoperoxide compound, methylene blue, among the 39 reference antimalarial drugs tested for assay validation. The values are averages ± SEM of two technical replicates (n = 2).

(ii) 8-Aminoquinolines.

Members of the 8-aminoquinoline compound class, especially primaquine, have been shown to possess gametocytocidal activity in P. falciparum-infected patients. Their activities against either early- or late/mature-stage gametocytes in vitro, however, have been moderate at best (15, 19, 20, 28). This discrepancy has been attributed to the requirement for the compounds to be metabolically transformed in order to exert activity, a process that does not occur in vitro (29). In our assay, NPC-1161B and tafenoquine showed weak gametocytocidal activity, with IC50s ± SEM of 2.03 ± 0.49 and 2.50 ± 0.004 μM, respectively. Primaquine and its derivative diethylprimaquine lacked any gametocytocidal activity, in line with previous observations of the same gametocyte stages (19).

(iii) Amino alcohols.

Two of the five compounds tested from the amino alcohol class, namely, halofantrine and mefloquine (racemic and the R and S isomers), killed late-stage gametocytes with limited potency, showing IC50s ranging between 2.31 and 3.39 μM. These levels of activity are lower than what has been reported in other late-stage (stage IV and V) gametocytocidal assays based on imaging and the measurement of metabolic activity (19, 30) and are in better agreement with recent chemiluminescence- and fluorescence-labeled antibody assays on functionally mature stage V gametocytes (18, 20).

(iv) Antibiotics.

Among the seven antibiotics tested, only thiostrepton showed moderate inhibition of late-stage gametocytes (IC50 ± SEM = 1.00 ± 0.07 and 2.31 ± 0.13 μM, respectively). Thiostrepton has previously been described as a late-stage gametocytocidal (19) and has exhibited activity against parasite gamete formation in other assays (18, 20, 27).

(v) 4-Aminoquinolines.

Compounds belonging to the 4-aminoquinoline class are known to be potent asexual- and early gametocyte stage inhibitors (15). Their activity has been reported to drop as gametocytogenesis progresses (16, 19, 31). Indeed, all 4-aminoquinolines tested (AQ-13, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, amodiaquine, naphthoquine, and piperaquine) failed to inhibit late-stage gametocytes in our assay.

(vi) Antifolates.

The antifolate class of compounds is known to inhibit asexual-stage parasites by blocking DNA synthesis and parasite replication. As the gametocyte does not divide, this class of compounds is not expected to exert gametocytocidal activity. Antifolates, however, have been shown to block male gamete formation, which entails rapid DNA replication and cell division via exflagellation (27). In our assay, chlorproguanil, and to a lesser extent proguanil, were found to inhibit late-stage gametocytes at high concentrations. These compounds have been previously reported as weakly active in an imaging-based late-stage gametocytocidal assay (19). This activity is unlikely to depend on the accepted mechanism of action of this class of compounds, namely, dihydrofolate reductase activity (32). An additional mechanism(s) of action might therefore exist, or the compounds might exert off-target toxicity at high concentrations.

(vii) Sulfonamides.

None of the three compounds tested from the sulfonamide chemical class showed any effect on late-stage gametocytes.

(viii) Others.

Five more compounds not belonging to any of the above-described classes were tested for activity against late-stage gametocytes: cycloheximide (glutarimides), pyronaridine (anilinoacridines), pentamidine (diamidines), atovaquone (naphthoquinones), and methylene blue (a heterocyclic aromatic dye). Atovaquone showed no gametocytocidal action, whereas pyronaridine and pentamidine weakly inhibited gametocytes, showing IC50s above 3 μM. Cycloheximide showed moderate gametocytocidal activity at 2.31 ± 0.13 μM. Methylene blue killed late-stage gametocytes with an IC50 of 38 ± 14 nM and was the most active nonendoperoxide compound (Fig. 2B). These results confirm previous findings on the same NF54 luciferase-expressing parasite line (19, 22), as well as other P. falciparum lines/strains (18, 27, 30).

Screening of chemical libraries.

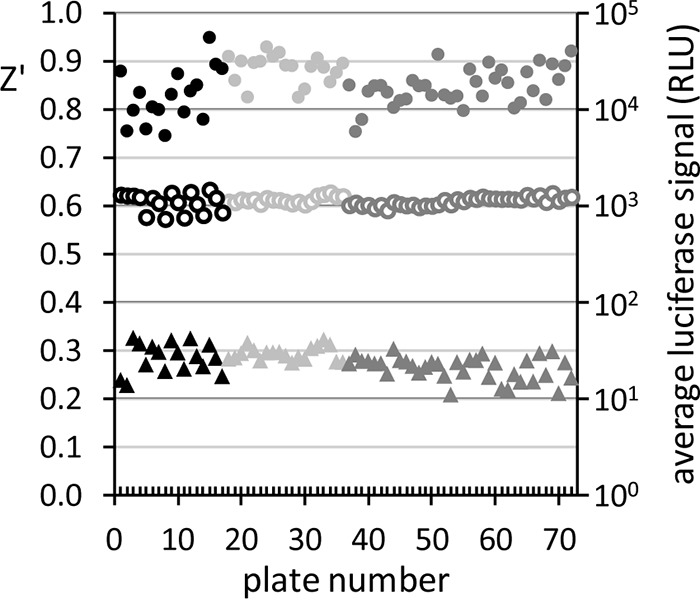

Our luciferase-based late-stage gametocytocidal assay was utilized to screen 10,050 compounds from three independent libraries. A total of 72 plates were assayed on 6 independent occasions, including the screening runs and the dose-response confirmation assays. The assay demonstrated excellent quality and reproducibility (Fig. 3) (average Z′ ± SEM = 0.852 ± 0.005; CV = 4.66% ± 0.17%; S/N = 815.1 ± 52.5).

FIG 3.

Summary of assay performance and reproducibility over multiple screening runs for MMV Malaria Box (black), ERS_01 (light gray), and GDB_04 (dark gray). Z′ values (filled circles; left y axis), averages of 0.4% DMSO (negative in-plate control; open circles; right y axis), and averages of 5 μM puromycin (positive in-plate control; triangles; right y axis) are given for each of the total 72 assay plates.

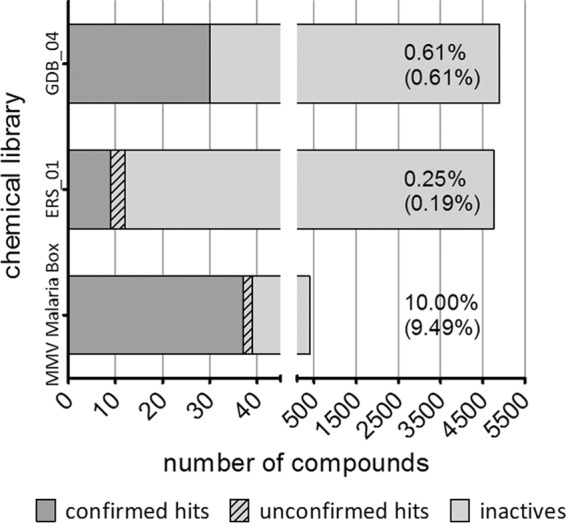

Figure 4 illustrates the screening outcomes. From the MMV Malaria Box, we identified 39 primary hits, 37 of which were confirmed for late-stage gametocytocidal activity by dose-response testing (9.49% final hit rate). The ERS_01 library yielded 12 primary hits, 9 of which were confirmed (0.19% final hit rate), and from the GDB_04 library, 30 primary hits were obtained, all of which were confirmed (0.61% final hit rate) for gametocytocidal activity. It is noteworthy that the above-mentioned hits were identified at different screening concentrations: 5 μM for the MMV Malaria Box, 4 μM for ERS_01, and 10 μM for GDB_04.

FIG 4.

Numbers of primary and confirmed late-stage gametocytocidal hits identified through the screening of three chemical libraries. The percentages represent the primary hit rate and the confirmed hit rate (parentheses) for each library.

The ERS_01 hits were retested for confirmation at 4.0, 1.0, 0.4, and 0.1 μM. While 9 compounds confirmed their activity at 4 μM, none of them showed any gametocytocidal effect at 1 μM concentration or below; therefore, the hits were not tested further.

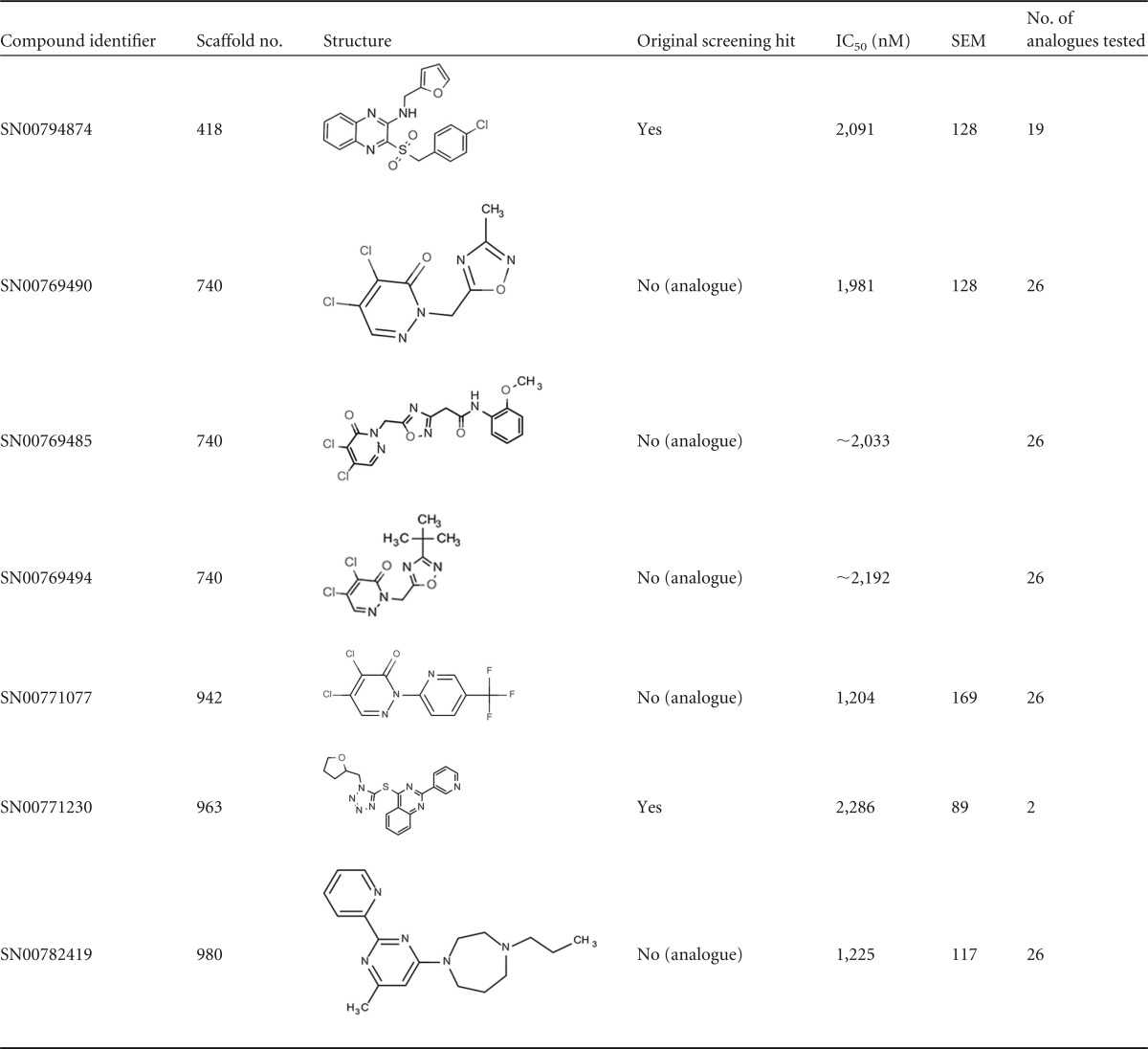

The 30 primary hits obtained from the GDB_04 library represented 24 different chemical scaffolds out of the 1,225 total scaffolds tested. We retested all the hits plus a variable number (0 to 28) of additional analogues for each active chemical scaffold, resulting in a total of 338 compounds tested in dose-response assays. Unfortunately, none of the retested compounds inhibited late-stage gametocytes potently, demonstrating only low micromolar IC50s. Table 1 shows the activities and structures of the most active compounds among the retested hits and their analogues. The majority of the active compounds were the single active representatives of scaffolds from which several analogues were tested. In some instances, they were analogues of the original hit compound. Only scaffold 740 included multiple analogue compounds with gametocytocidal activity, namely, SN00769490, SN00769485, and SN00769494. These three compounds, however, were the only potent compounds among the 26 scaffold 740 analogues that were tested in dose-response assays. Compound SN00771077, from the related scaffold 942, was also the only active analogue from a batch of 26 representatives.

TABLE 1.

Structures and activities of late-stage gametocytocidal compounds from the GDB_04 scaffold library

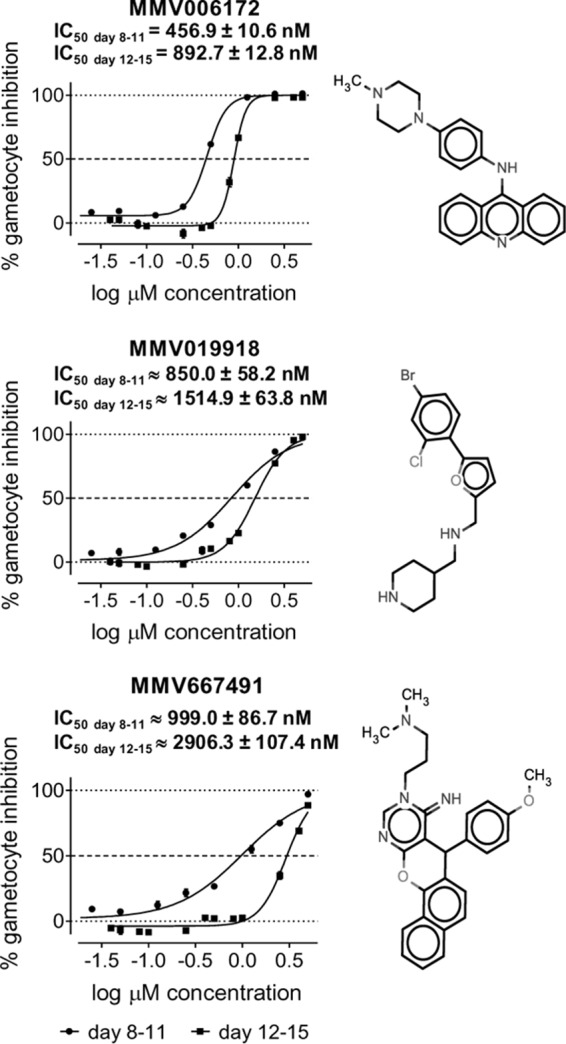

Of the 39 primary hits obtained from screening the MMV Malaria Box, 32 compounds were confirmed for late-stage gametocytocidal activity, with more than 50% inhibition at the top concentration of 5 μM. Following a retest, five more primary hits inhibited gametocytes by more than 45% at 5 μM, while two other compounds resulted in 11% and 16% inhibition at 5 μM and thus were not confirmed (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Due to the limited amount of compound available for retesting, the dose-response assays were carried out with a highest concentration of 5 μM. Under these conditions, the inhibition curves did not reach a 100% inhibition plateau for most of the compounds tested. The respective IC50s obtained, while assumed to be close to the actual figures, have to be considered as approximate. Within the limits of this estimation, three compounds were confirmed hits, MMV006172, MMV019918, and MMV667491. These compounds showed activity in the submicromolar range (IC50s, 456 nM, 850 nM, and 999 nM, respectively), and an additional 14 compounds exhibited IC50s below 2 μM (Fig. 5; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The three most active compounds (MMV006172, MMV019918, and MMV667491) were then retested in dose-response assays against mature stage V gametocytes to assess their activities against this more transmission-relevant stage. All of the compounds were confirmed to be similarly active against these mature (post-day 12) gametocyte stages, although with reduced IC50s, with MMV667491 showing the largest (3-fold) difference in activity between day 8 and day 12 gametocytes.

FIG 5.

Late- and mature-stage gametocytocidal activities and structures of the three most potent late-stage P. falciparum gametocyte inhibitors identified in the MMV Malaria Box.

Assessment of the compound activity profile throughout gametocytogenesis.

A new profiling method was developed to enable the fine assessment of the variation in the drug sensitivity of gametocytes during their entire development.

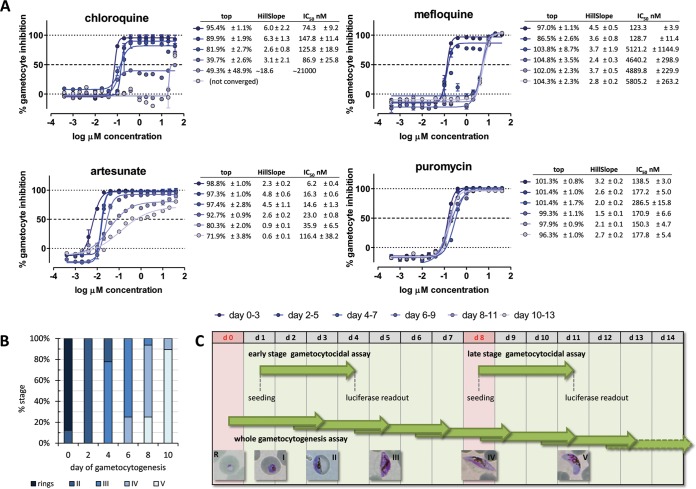

The activities of four gametocytocidal compounds belonging to four independent chemical classes, namely, chloroquine, mefloquine, artesunate, and puromycin, were assessed for their efficacy throughout the process of gametocytogenesis by determining their inhibitory effects at 6 time points: days 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 of gametocytogenesis after a 72-h-long exposure to compounds (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

(A) Proof of principle of the whole-gametocytogenesis assay showing temporal activity profiles of four gametocytocidal compounds. (B) Stage composition of the cultures used in the experiment. (C) Diagram showing the timing of our late-stage luciferase gametocytocidal assay compared to our early-stage assay reported previously (15) and the design of the whole-gametocytogenesis assay. Time is expressed as the day (d) of gametocytogenesis, and the days shaded red correspond to the times of magnetic purification of gametocytes.

A decrease in the gametocytocidal activity as gametocytogenesis progressed was observed for all compounds with the exception of puromycin. The changes in the relationship between dose and effect over time, however, assumed markedly distinct compound-dependent patterns, with the IC50, the inhibition plateau, or the curve's slope being the main parameter that changed (Fig. 6A). Chloroquine lost activity starting on day 6 of gametocytogenesis (readout on day 9), when the exposed parasite population consisted of 75% stage III and 25% stage IV gametocytes (Fig. 6B). A drop in the inhibition plateau to 40% was observed initially, followed by an abrupt increase in the IC50 on day 8 and finally by complete inactivity on day 10.

The pattern of gametocyte desensitization to mefloquine was clearly distinct. A sudden 40-fold shift in the IC50 of the drug from 120 nM to 5 μM was observed by day 4 (readout on day 7; initial stage composition, 22% stage II and 78% stage III). No changes in the value of the inhibition plateau or the inhibition curve slope were observed. The IC50 remained constant from day 4 onward.

In the case of artesunate, a more gradual decrease in the IC50 was observed at each consecutive time point, with the slope of the inhibition curve being the most prominent changing feature after day 6. The overall reduction in activity was about 20-fold from day 0 to day 10 of gametocytogenesis.

Puromycin represented the ideal control compound for this experiment, with remarkably constant activity throughout gametocytogenesis (overall variation of IC50 and slope, approximately 2-fold). Our proof-of-principle assessment of gametocyte chemosensitivity across their entire development showed excellent performance, with average Z′ values of 0.92 ± 0.02, 0.86 ± 0.02, 0.84 ± 0.04, 0.91 ± 0.01, 0.79 ± 0.04, and 0.80 ± 0.13 on readout days 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We have described the optimization, validation, and application of an HTS-compatible biochemical assay for late-stage P. falciparum gametocytes, utilizing the gametocyte-specific reporter gene line NF54Pfs16 (22), whose gametocytes express a luciferase-GFP fusion protein. Previously, this parasite line was used to establish a manual assay in 96-well format to assess the activities of reference compounds against multiple gametocyte stages (22). The assay described here builds on our previously published fully optimized robust HTS assay for early-stage (stage I to III) gametocytes (15), which has now been extended to assess compound activity against later-stage (stage IV and V) gametocytes. The promoter driving the expression of luciferase in the NF54Pfs16 line, Pfs16, is expressed throughout gametocytogenesis (33). Therefore, NF54Pfs16 is suitable for use as a reporter gene line for late-stage gametocyte assays (19); this line is available to the scientific community.

The test of 39 reference antimalarial compounds showed excellent agreement between our assay and the existing literature. An exception was the aminoalcohol mefloquine, for which discordant results have been reported in previous assays (IC50 range, 100 nM to 7.5 μM [18–20, 28, 30]). The reasons for this discrepancy are difficult to identify, and any comparison of different gametocytocidal assays has to be done cautiously, since every assay is a multivariate system defined by the stage assessed, the technology used, the duration of exposure to compounds, and the additional incubation time after the addition of detection reagents. The handling and physicochemical properties of compounds can also play a role in the final outcome, especially if potential liabilities exist, such as poor solubility in water, as in the case of mefloquine (34).

Our late-stage gametocytocidal assay showed excellent performance and reproducibility, with an average assay Z′ value of 0.85 obtained from a total of 72 384-well plates to date and a 93.8% overall confirmation rate from multiple screening activities encompassing more than 10,000 compounds.

The screening of both unbiased and antimalarial-enriched libraries with our assay allowed us to compare the respective late-stage gametocytocidal hit rates. The extremely low hit rate of 0.43% obtained from the screening of unbiased libraries is in agreement with the outcome of a previously reported alamarBlue screening on late-stage P. falciparum gametocytes (30). In contrast, starting from a chemical library enriched for antimalarial compounds, such as the MMV Malaria Box, proved more promising, with about 10% of the compounds qualifying as hits (a 23-fold-increased hit rate). While this confirms the fact that P. falciparum gametocytes are less sensitive than asexual stages to many antimalarial drugs, as has been previously shown for both early-stage (15) and late-stage (19) gametocytes, it also suggests that screening asexual-stage inhibitors for gametocytocidal activity increases the likelihood of identifying relevant compounds for drug development. This relationship is particularly useful given the current focus in antimalarial drug discovery and development on compounds with dual asexual and transmission-blocking activity (35–38). The most active gametocytocidal compounds identified in our screening were from the MMV Malaria Box. Specifically, compounds MMV006172, MMV019918, and MMV667491 showed submicromolar activities against late-stage gametocytes in our assay. Given that all of the compounds have been identified previously in other gametocytocidal assays, possible direct inhibition of the luciferase enzyme was ruled out. The most potent compound, MMV006172, is a probe-like compound previously found to be active in our imaging assay against gametocytes at the same maturation level as our day 8 luciferase assay (stages IV and V), with an IC50 of 1.36 μM (19). The gametocytocidal activity of the compound was also reported in several other gametocytocidal assays, although it was seen to have varying potency: parasite lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) (IC50 = 0.73 μM [38]), SYBR green I (IC50 = 2.6 μM [39]), and two alamarBlue assays (IC50 = 0.42 μM [40] and 1.48 μM [30]). The compound was also described as a female gamete formation inhibitor (IC50 = 0.46 μM [21]) and as an early-stage gametocyte inhibitor in both our luciferase (15) and imaging (19) assays, with IC50s of 1.21 μM and 1.11 μM, respectively.

The next most active compound, the drug-like MMV019918, had also been identified in all published late-stage gametocytocidal screens so far, with submicromolar IC50s ranging between 0.32 μM and 0.89 μM obtained in four assays (19, 38–40) and slightly lower activities (1.06 μM and 1.87 μM) reported in two other studies (21, 30). The compound has also been shown to be a moderate early-stage inhibitor in both our luciferase and imaging assays, with IC50s of 1.56 μM (15) and 0.82 μM (19), respectively.

The last inhibitor showing submicromolar late-stage gametocytocidal activity in our assay was the probe-like MMV667491, which had been previously identified either as inactive (40) or as a moderately active gametocytocidal compound, with IC50s in the 0.70 to 4.46 μM range (30, 38, 39). In our imaging-based assay, the compound showed an IC50 of 1.06 μM against late-stage gametocytes. MMV667491 was also shown to be moderately active against developing gametocytes in our early-stage luciferase assay (IC50 = 1.58 μM) (15), but not in our early-stage imaging assay (19).

Recently, several assays measuring the inhibitory activities of compounds against mature stage V gametocytes have been described. Some assays have focused on gamete formation after xanthurenic acid (XA)-mediated activation of gametocytes (18, 20, 21, 41) or, alternatively, have been based on the measurement of pLDH activity from non-XA-activated gametocyte cultures (18). Functional-viability assays targeting mature gametocytes, i.e., the stage that is competent for transmission in the mosquito, have been proposed as more accurate predictors of the transmission-blocking potential of compounds (41). We therefore tested the most potent Malaria Box compounds identified in our gametocyte assay using mature stage V gametocytes on day 12 of gametocytogenesis. All three compounds maintained activity against these more mature gametocytes, albeit at slightly lower levels, not necessarily reflective of reduced potency (1.9- to 2.9-fold difference range). The most active compound from the day 8 screening, MMV006172, was still active on day 12 at a submicromolar level. The compound was shown to be a weak male-specific gametocyte/gamete formation inhibitor, causing 56.4% inhibition of male gametogenesis at 1 μM, while being inactive against female gametocytes at the same concentration in a screen evaluating male and female gamete formation (41). More recently, an imaging-based assay reported the compound as a female gamete formation inhibitor (IC50 = 0.46 μM [21]). The next four most active compounds in our assay (MMV019918, MMV667491, MMV000448, and MMV66594) were all described as gamete formation inhibitors (21, 41). Finally, MMV085203, which inhibited late-stage gametocytes with an IC50 of 1.24 μM, was reported as a male-specific irreversible inhibitor (41) with no obvious effect against female gamete formation (21, 41).

Assays with high throughput capability (i.e., using 384- or 1,536-well plates) utilizing fluorescent indicators of metabolic activity (17, 18, 38) or expression of GFP coupled with a fluorescent indicator of mitochondrial activity (19) have been described in the past for late-stage P. falciparum gametocytes (variably encompassing stages III to V). In addition, assays measuring the functional viability of mature stage V female gametocytes have been proposed, based on fluorescence imaging (20, 21) and chemiluminescence (18). However, to date, most published late-stage/mature gametocyte HTS assays require several hours of extra incubation of live parasites at the end of the nominal assay duration to ensure sufficient signal intensity after the detection reagents have been added. Our luciferase assay can be read 1 h after the addition of the detection reagent Steadylite, which combines a lysis buffer and a luciferase substrate; therefore, the readout obtained throughout the available >6-h window reflects only the effect of the 72-h (or any other desired duration) exposure to compounds.

Not being based on imaging of the individual luciferase-expressing cells, our assay has the limitation of not assessing parasite phenotypes that could be related to viability. The luminescence readout, however, reflects luciferase expression of the entire gametocyte population in each well on a quantitative level and is much less affected by the variability that can affect individual cell count approaches in imaging assays. Our assay is robust, as demonstrated by the Z′ and high confirmation rates obtained. Additionally, a complete 384-well plate requires only 3 to 4 min to read, and therefore, the throughput of this rapid assay is limited only by the volume of the available gametocyte culture for screening. Our protocol to induce gametocytes employs two magnetic-purification rounds: on day 0 on sorbitol-synchronized asexual stages to ensure the highest synchronicity of the parasites undergoing sexual commitment and again on day 8 to obtain a pure, highly concentrated gametocyte culture for screening. The pure synchronous nature of our gametocytes enables a strong signal to be obtained from a relatively small number of gametocytes per well. A standard gametocyte induction for screening starts with 270 ml culture on day −3 and has a typical day 8 yield of 0.5 × 108 to 1.4 × 108 gametocytes in ∼60-ml final volume. To screen a single 384-well plate, a starting volume equivalent to 4.3 ± 0.4 ml of preinduction (day −3; n = 7) parasite culture is sufficient. At full capacity, 120,000 compounds can be screened per week in our hands (however, the theoretical throughput based on the readout time is ∼170,000 compounds in 24 h, if the plates are added with the Steadylite kit in a 6-h staggered fashion). A final important aspect of our HTS late-stage assay is its cost-effectiveness. Compared to the conditions applied in the manual 96-well-plate luciferase assay originally described by Adjalley et al. (22), a 13.2-fold reduction in the number of gametocytes required per well is achieved by miniaturization to the 384-well HTS format. This corresponds to a minimum 70% saving in the overall assay cost. Minor adaptations would allow the assay to be run in the 1,536-well plate format, which would increase throughput and thus further reduce costs. Our assay can be run in any laboratory with Plasmodium gametocyte-culturing capability and a luminometer and thus represents an approachable method for the determination of gametocytocidal activity, in addition to its HTS application.

The successful development of a luciferase-based, late-stage gametocytocidal assay using the same recombinant parasite line as our previously reported early-stage assay (15) allowed the direct comparison of early- and late-stage gametocytocidal effects of drugs and compounds and thus offered an opportunity to assess the dynamics of gametocyte chemosensitivity over the entire course of gametocytogenesis. Since our NF54Pfs16 line expresses the luciferase enzyme only during the gametocyte stage, there is no risk of detection interference with asexual stages in mixed populations. We are therefore in a unique position to conduct sensitive and robust quantification of the gametocytocidal activity of a compound from day 0 of gametocytogenesis, when parasite populations are typically a mixture of asexual ring stages and ring-stage gametocytes. This is a particularly useful application, because it allows direct testing of the effects of compounds on the gametocyte ring stage, the only immature sexual stage that is found in the peripheral blood before the onset of organ sequestration (42). Our study is the first report of an assay that can assess compound activity against the complete process of gametocytogenesis in a miniaturized, truly HTS format, thus providing the opportunity to carry out extensive characterization of the gametocytocidal activity of limited quantities of newly synthesized experimental compounds.

The characterization of the gametocytocidal activities of reference antimalarial drugs over time showed an abrupt decrease in drug activity after day 6 of gametocytogenesis in all cases. This observation is in agreement with the findings of a previous flow cytometry-based study describing a sudden drop in the gametocytocidal activity of chloroquine, pyronaridine, and dihydroartemisinin after day 7 of gametocytogenesis (16) and confirms the gametocyte stage III and the transition from stage III to stage IV as the stages when a major chemosensitivity shift in developing gametocytes occurs.

Our proof-of-principle, whole-gametocytogenesis assay with four gametocytocidal compounds from unrelated classes demonstrates the feasibility and robustness of this HTS whole-gametocytogenesis assay. The assay can be adapted to cover the whole gametocytogenesis process or any portions of it, and because there is no extra incubation after detection reagents are added, any duration of compound exposure can be assessed. The HTS format of this combined assay also enables it to be miniaturized, thus allowing the profiling of gametocytocidal activity for small samples of compounds.

In conclusion, we have described the successful adaptation and optimization of previously reported luciferase-based gametocytocidal assays (15, 22) to a rapid, robust, and cost-effective HTS assay to identify new chemical entities with malaria transmission-blocking potential from the screening of large chemical libraries against late-stage P. falciparum gametocytes. In addition, we have demonstrated the potential for this assay to be used to profile the transmission-blocking activities of the candidate compounds throughout gametocytogenesis in a miniaturized format and to be easily adapted to any facility with malaria parasite-culturing capability and common biochemistry equipment. The assay will be useful to facilitate the current efforts in the discovery and development of new drugs for malaria elimination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medicines for Malaria Venture is gratefully acknowledged for the assembly and supply of the Malaria Box. We thank Shane Maher and Sasdekumar Loganathan, Griffith University, for their assistance with gametocyte culturing. The Australian Red Cross Blood Service is gratefully acknowledged for the provision of human erythrocytes.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01949-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carter R, Miller LH. 1979. Evidence for environmental modulation of gametocytogenesis in Plasmodium falciparum in continuous culture. Bull World Health Organ 57(Suppl 1):S37–S52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bousema T, Drakeley C. 2011. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:377–410. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 2015. World malaria report. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2015/en/ Accessed 12 February 2016.

- 4.Liu J, Modrek S, Gosling RD, Feachem RG. 2013. Malaria eradication: is it possible? Is it worth it? Should we do it? Lancet Glob Health 1:e2-3. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dondorp AM, Yeung S, White L, Nguon C, Day NP, Socheat D, von Seidlein L. 2010. Artemisinin resistance: current status and scenarios for containment. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:272–280. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straimer J, Gnadig NF, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Duru V, Ramadani AP, Dacheux M, Khim N, Zhang L, Lam S, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Benoit-Vical F, Fairhurst RM, Menard D, Fidock DA. 2015. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science 347:428–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1260867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok S, Ashley EA, Ferreira PE, Zhu L, Lin Z, Yeo T, Chotivanich K, Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Dhorda M, Nguon C, Lim P, Amaratunga C, Suon S, Hien TT, Htut Y, Faiz MA, Onyamboko MA, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Tripura R, Woodrow CJ, Miotto O, Kwiatkowski DP, Nosten F, Day NP, Preiser PR, White NJ, Dondorp AM, Fairhurst RM, Bozdech Z. 2015. Population transcriptomics of human malaria parasites reveals the mechanism of artemisinin resistance. Science 347:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1260403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranson H, N′Guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V. 2011. Pyrethroid resistance in African anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control? Trends Parasitol 27:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fidock DA. 2013. Microbiology. Eliminating malaria. Science 340:1531–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1240539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells TN, van Huijsduijnen RH, Van Voorhis WC. 2015. Malaria medicines: a glass half full? Nat Rev Drug Discov 14:424–442. doi: 10.1038/nrd4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Phyo AP, Rueangweerayut R, Nosten F, Jittamala P, Jeeyapant A, Jain JP, Lefevre G, Li R, Magnusson B, Diagana TT, Leong FJ. 2014. Spiroindolone KAE609 for falciparum and vivax malaria. N Engl J Med 371:403–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leong FJ, Zhao R, Zeng S, Magnusson B, Diagana TT, Pertel P. 2014. A first-in-human randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single- and multiple-ascending oral dose study of novel imidazolopiperazine KAF156 to assess its safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics in healthy adult volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6437–6443. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03478-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burrows JN, van Huijsduijnen RH, Mohrle JJ, Oeuvray C, Wells TN. 2013. Designing the next generation of medicines for malaria control and eradication. Malar J 12:187. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchholz K, Burke TA, Williamson KC, Wiegand RC, Wirth DF, Marti M. 2011. A high-throughput screen targeting malaria transmission stages opens new avenues for drug development. J Infect Dis 203:1445–1453. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucantoni L, Duffy S, Adjalley SH, Fidock DA, Avery VM. 2013. Identification of MMV malaria box inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum early-stage gametocytes using a luciferase-based high-throughput assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:6050–6062. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00870-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Liu M, Liang X, Siriwat S, Li X, Chen X, Parker DM, Miao J, Cui L. 2014. A flow cytometry-based quantitative drug sensitivity assay for all Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte stages. PLoS One 9:e93825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka TQ, Dehdashti SJ, Nguyen DT, McKew JC, Zheng W, Williamson KC. 2013. A quantitative high throughput assay for identifying gametocytocidal compounds. Mol Biochem Parasitol 188:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolscher JM, Koolen KM, van Gemert GJ, van de Vegte-Bolmer MG, Bousema T, Leroy D, Sauerwein RW, Dechering KJ. 2015. A combination of new screening assays for prioritization of transmission-blocking antimalarials reveals distinct dynamics of marketed and experimental drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1357–1366. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy S, Avery VM. 2013. Identification of inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte development. Malar J 12:408. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miguel-Blanco C, Lelievre J, Delves MJ, Bardera AI, Presa JL, Lopez-Barragan MJ, Ruecker A, Marques S, Sinden RE, Herreros E. 2015. Imaging-based HTS assay to identify new molecules with transmission-blocking potential against P. falciparum female gamete formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3298–3305. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04684-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucantoni L, Silvestrini F, Signore M, Siciliano G, Eldering M, Dechering KJ, Avery VM, Alano P. 2015. A simple and predictive phenotypic high content imaging assay for Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes to identify malaria transmission blocking compounds. Sci Rep 5:16414. doi: 10.1038/srep16414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adjalley SH, Johnston GL, Li T, Eastman RT, Ekland EH, Eappen AG, Richman A, Sim BK, Lee MC, Hoffman SL, Fidock DA. 2011. Quantitative assessment of Plasmodium falciparum sexual development reveals potent transmission-blocking activity by methylene blue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:E1214–E1223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trager W, Jensen JB. 1976. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. 1999. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spangenberg T, Burrows JN, Kowalczyk P, McDonald S, Wells TN, Willis P. 2013. The open access malaria box: a drug discovery catalyst for neglected diseases. PLoS One 8:e62906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azevedo MF, Nie CQ, Elsworth B, Charnaud SC, Sanders PR, Crabb BS, Gilson PR. 2014. Plasmodium falciparum transfected with ultra bright NanoLuc luciferase offers high sensitivity detection for the screening of growth and cellular trafficking inhibitors. PLoS One 9:e112571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delves MJ, Ruecker A, Straschil U, Lelievre J, Marques S, Lopez-Barragan MJ, Herreros E, Sinden RE. 2013. Male and female Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes show different responses to antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3268–3274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00325-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lelievre J, Almela MJ, Lozano S, Miguel C, Franco V, Leroy D, Herreros E. 2012. Activity of clinically relevant antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes in an ATP bioluminescence “transmission blocking” assay. PLoS One 7:e35019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vale N, Moreira R, Gomes P. 2009. Primaquine revisited six decades after its discovery. Eur J Med Chem 44:937–953. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun W, Tanaka TQ, Magle CT, Huang W, Southall N, Huang R, Dehdashti SJ, McKew JC, Williamson KC, Zheng W. 2014. Chemical signatures and new drug targets for gametocytocidal drug development. Sci Rep 4:3743. doi: 10.1038/srep03743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cevenini L, Camarda G, Michelini E, Siciliano G, Calabretta MM, Bona R, Kumar TR, Cara A, Branchini BR, Fidock DA, Roda A, Alano P. 2014. Multicolor bioluminescence boosts malaria research: quantitative dual-color assay and single-cell imaging in Plasmodium falciparum parasites. Anal Chem 86:8814–8821. doi: 10.1021/ac502098w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller IB, Hyde JE. 2010. Antimalarial drugs: modes of action and mechanisms of parasite resistance. Future Microbiol 5:1857–1873. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dechering KJ, Thompson J, Dodemont HJ, Eling W, Konings RN. 1997. Developmentally regulated expression of pfs16, a marker for sexual differentiation of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 89:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasim NA, Whitehouse M, Ramachandran C, Bermejo M, Lennernas H, Hussain AS, Junginger HE, Stavchansky SA, Midha KK, Shah VP, Amidon GL. 2004. Molecular properties of WHO essential drugs and provisional biopharmaceutical classification. Mol Pharm 1:85–96. doi: 10.1021/mp034006h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leroy D, Campo B, Ding XC, Burrows JN, Cherbuin S. 2014. Defining the biology component of the drug discovery strategy for malaria eradication. Trends Parasitol 30:478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaidya AB, Morrisey JM, Zhang Z, Das S, Daly TM, Otto TD, Spillman NJ, Wyvratt M, Siegl P, Marfurt J, Wirjanata G, Sebayang BF, Price RN, Chatterjee A, Nagle A, Stasiak M, Charman SA, Angulo-Barturen I, Ferrer S, Belen Jimenez-Diaz M, Martinez MS, Gamo FJ, Avery VM, Ruecker A, Delves M, Kirk K, Berriman M, Kortagere S, Burrows J, Fan E, Bergman LW. 2014. Pyrazoleamide compounds are potent antimalarials that target Na+ homeostasis in intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun 5:5521. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baragana B, Hallyburton I, Lee MC, Norcross NR, Grimaldi R, Otto TD, Proto WR, Blagborough AM, Meister S, Wirjanata G, Ruecker A, Upton LM, Abraham TS, Almeida MJ, Pradhan A, Porzelle A, Martinez MS, Bolscher JM, Woodland A, Norval S, Zuccotto F, Thomas J, Simeons F, Stojanovski L, Osuna-Cabello M, Brock PM, Churcher TS, Sala KA, Zakutansky SE, Jimenez-Diaz MB, Sanz LM, Riley J, Basak R, Campbell M, Avery VM, Sauerwein RW, Dechering KJ, Noviyanti R, Campo B, Frearson JA, Angulo-Barturen I, Ferrer-Bazaga S, Gamo FJ, Wyatt PG, Leroy D, Siegl P, Delves MJ, Kyle DE, Wittlin S, Marfurt J, Price RN, Sinden RE, Winzeler EA, Charman SA, Bebrevska L, Gray DW, Campbell S, Fairlamb AH, Willis PA, Rayner JC, Fidock DA, Read KD, Gilbert IH. 2015. A novel multiple-stage antimalarial agent that inhibits protein synthesis. Nature 522:315–320. doi: 10.1038/nature14451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plouffe DM, Wree M, Du AY, Meister S, Li F, Patra K, Lubar A, Okitsu SL, Flannery EL, Kato N, Tanaseichuk O, Comer E, Zhou B, Kuhen K, Zhou Y, Leroy D, Schreiber SL, Scherer CA, Vinetz J, Winzeler EA. 2016. High-throughput assay and discovery of small molecules that interrupt malaria transmission. Cell Host Microbe 19:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanders NG, Sullivan DJ, Mlambo G, Dimopoulos G, Tripathi AK. 2014. Gametocytocidal screen identifies novel chemical classes with Plasmodium falciparum transmission blocking activity. PLoS One 9:e105817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman JD, Merino EF, Brooks CF, Striepen B, Carlier PR, Cassera MB. 2014. Antiapicoplast and gametocytocidal screening to identify the mechanisms of action of compounds within the malaria box. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:811–819. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01500-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruecker A, Mathias DK, Straschil U, Churcher TS, Dinglasan RR, Leroy D, Sinden RE, Delves MJ. 2014. A male and female gametocyte functional viability assay to identify biologically relevant malaria transmission-blocking drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7292–7302. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03666-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelle KG, Oh K, Buchholz K, Narasimhan V, Joice R, Milner DA, Brancucci NM, Ma S, Voss TS, Ketman K, Seydel KB, Taylor TE, Barteneva NS, Huttenhower C, Marti M. 2015. Transcriptional profiling defines dynamics of parasite tissue sequestration during malaria infection. Genome Med 7:19. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.