Abstract

The linezolid experience and accurate determination of resistance (LEADER) surveillance program has monitored linezolid activity, spectrum, and resistance since 2004. In 2014, a total of 6,865 Gram-positive pathogens from 60 medical centers from 36 states were submitted. The organism groups evaluated were Staphylococcus aureus (3,106), coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS; 797), enterococci (855), Streptococcus pneumoniae (874), viridans group streptococci (359), and beta-hemolytic streptococci (874). Susceptibility testing was performed by reference broth microdilution at the monitoring laboratory. Linezolid-resistant isolates were confirmed by repeat testing. PCR and sequencing were performed to detect mutations in 23S rRNA, L3, L4, and L22 proteins and acquired genes (cfr and optrA). The MIC50/90 for Staphylococcus aureus was 1/1 μg/ml, with 47.2% of isolates being methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Linezolid was active against all Streptococcus pneumoniae strains and beta-hemolytic streptococci with a MIC50/90 of 1/1 μg/ml and against viridans group streptococci with a MIC50/90 of 0.5/1 μg/ml. Among the linezolid-nonsusceptible MRSA strains, one strain harbored cfr only (MIC, 4 μg/ml), one harbored G2576T (MIC, 8 μg/ml), and one contained cfr and G2576T with L3 changes (MIC, ≥8 μg/ml). Among CoNS, 0.75% (six isolates) of all strains demonstrated linezolid MIC results of ≥4 μg/ml. Five of these were identified as Staphylococcus epidermidis, four of which contained cfr in addition to the presence of mutations in the ribosomal proteins L3 and L4, alone or in combination with 23S rRNA (G2576T) mutations. Six enterococci (0.7%) were linezolid nonsusceptible (≥4 μg/ml; five with G2576T mutations, including one with an additional cfr gene, and one strain with optrA only). Linezolid demonstrated excellent activity and a sustained susceptibility rate of 99.78% overall.

INTRODUCTION

The LEADER (linezolid experience and accurate determination of resistance) program is a national surveillance program which was initiated in 2004 to track the activity of linezolid, in the context of the activity of other Gram-positive agents, against staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci (1). This program has provided information on a yearly basis about linezolid resistance mechanisms, including the identification of emerging mechanisms. Throughout the tenure of LEADER, overall linezolid resistance in Gram-positive bacteria has evolved to include new species and mechanisms; however, the overall linezolid resistance rate has remained modest at <1% (1–9).

Linezolid, an oxazolidinone, exerts its antibacterial activity by inhibiting protein synthesis by binding to the 23S subunit of the 50S ribosome (10–13). Resistance development appeared early in clinical use in staphylococci and enterococci through ribosomal mutation in the 23S rRNA at G2576T (14, 15). Later on, an rRNA methyltransferase occurred which conferred resistance not only to linezolid but also to other antimicrobial agents (16–18). This cfr rRNA methyltransferase has the potential to mobilize, and although it has occurred in a broader range of species and with more frequency, it still is not the dominant form of linezolid resistance (5, 6, 8, 9, 19).

In this study, we report the activity of linezolid against Gram-positive bacteria collected during the calendar year 2014. A total of 6,865 Gram-positive pathogens were selected from 60 U.S. medical centers from 36 states for the following groups of organisms: Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), enterococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, β-hemolytic streptococci, and viridans group streptococci.

(This work was presented in part in abstract form at the 2015 IDWeek meeting in San Diego, CA.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism collection.

During 2014, a total of 6,865 Gram-positive bacterial pathogens were collected from 60 medical centers in 36 states across all nine U.S. Census Bureau regions. There were 4 to 9 medical centers in each U.S. Census Bureau region, and a total of 495 to 1,100 strains were contributed per region.

Each laboratory followed a protocol to submit consecutive isolates (one per patient episode) determined to be pathogens to the monitoring laboratory. The isolates were primarily from invasive bloodstream infections (BSI), pneumonia (respiratory tract), and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI), although isolates from other sites were acceptable. The target organisms requested from each medical center were Staphylococcus aureus (50 isolates), CoNS (15 isolates), enterococci (15 isolates), Streptococcus pneumoniae (10 isolates), and beta-hemolytic streptococci and viridans group or other streptococci (five isolates each; total of 10). The monitoring laboratory (JMI Laboratories, North Liberty, IA) confirmed the bacterial identification received from the participant medical center using biochemical methods or matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) as appropriate.

Susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility tests and the confirmation of linezolid-resistant isolates were performed as described previously (4–6, 8, 9). Briefly, broth microdilution method tests were performed at the monitoring reference laboratory using dry-form panels produced by Thermo Fisher (formerly TREK Diagnostics, Cleveland, OH) applying Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) methods and published interpretive criteria (20, 21). Linezolid-resistant isolates were confirmed by repeat reference broth microdilution testing (20) using frozen-form broth microdilution panels and with the linezolid Etest (AB Biodisk; bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO) and CLSI disk diffusion susceptibility testing methods (21, 22).

Molecular characterization.

Molecular testing was performed as previously described on isolates exhibiting elevated linezolid MIC results (MIC, ≥4 μg/ml) to identify recognized target site mutations or genes and potential clonality using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The PFGE profile pattern nomenclature that we used consisted of three types of information. PFGE type was assigned according to the isolate code (initials represent the organism), site identifier (internal JMI institution number), and a capital letter for the PFGE group; e.g., SA468A was an Staphylococcus aureus isolate from JMI site 468 that was PFGE group A. Staphylococci and enterococci were screened for cfr, optrA, and mutations in the central loop of the domain V region of 23S rRNA as well as L3 and L4 ribosomal proteins (16, 23–26). Staphylococcus aureus strains that were resistant to erythromycin but susceptible to clindamycin were screened for inducible clindamycin resistance (21).

RESULTS

Activity against Staphylococcus aureus.

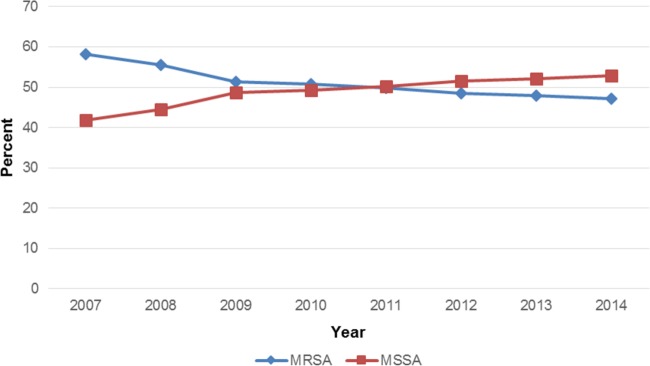

Susceptibility rates for erythromycin, the fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin were lower for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) than for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (Table 1). For example, susceptibility to erythromycin was 10.7% for MRSA and 65.9% for MSSA (Table 1). Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin ranged from 28.6 to 31.0% for MRSA and 86.1 to 88.8% for MSSA (Table 1). Resistance to clindamycin for MRSA was 26.8% (34.0% when taking into account isolates which were shown to be inducible), while for MSSA the rate was 5.2% (14.5%). Staphylococcus aureus exhibited a high level of susceptibility to linezolid (MSSA, 100.0% susceptible; MRSA, 99.9%), tigecycline (all Staphylococcus aureus strains were susceptible), teicoplanin (all Staphylococcus aureus strains were susceptible), daptomycin (MSSA, 100.0% susceptible; MRSA, 99.9%), and vancomycin (all Staphylococcus aureus strains were susceptible) (Table 1). The overall MRSA rate was 47.2% (Table 1 and Fig. 1). This rate has decreased each year in the LEADER program from a high of 58.2% (2007) (Fig. 1). The MRSA rate varied by region in 2014 from 40.0% (New England and west north central) to 57.0% (east south central) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparative activity of linezolid tested against 6,865 Gram-positive pathogens isolated during the 2014 LEADER program

| Organism and resistance group (no. tested per antimicrobial agent) | MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | % Sensitive/% resistanta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||||

| Oxacillin susceptible (1,641) | ||||

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | 0.25–2 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 1 | 0.25–2 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Teicoplanin | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤2–≤2 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–1 | 100.0/— |

| Erythromycin | 0.25 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 65.9/27.4 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25–>2 | 94.6/5.2 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5–>8 | 95.7/3.6 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1–>8 | 99.0/1.0 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 88.8/10.8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | >4 | ≤0.03–>4 | 86.1/11.5 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5–>4 | 99.3/0.7 |

| Oxacillin resistant (1,465) | ||||

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | 0.25–>8 | 99.9/0.1 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 1 | 0.25–2 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Teicoplanin | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤2–4 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12–2 | 99.9/— |

| Erythromycin | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 10.7/85.2 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | >2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 72.8/26.8 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≤0.5–>8 | 95.0/4.4 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1–>8 | 96.3/3.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 4 | >4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 31.0/67.9 |

| Ciprofloxacin | >4 | >4 | 0.12–>4 | 28.6/69.0 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5–>4 | 97.7/2.3 |

| CoNS | ||||

| Oxacillin susceptiblec (340) | ||||

| Linezolid | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–>8 | 99.7/0.3 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 2 | 0.25–2 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Teicoplanin | ≤2 | 4 | ≤2–16 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–2 | 99.7/— |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 64.7/32.9 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | 2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 89.1/9.7 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5 | 4 | ≤0.5–>8 | 91.2/8.0 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 100.0/— |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1–>8 | 97.1/2.1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 85.0/14.1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 85.0/14.4 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤0.5 | 2 | ≤0.5–>4 | 90.3/9.7 |

| Oxacillin resistantd (457) | ||||

| Linezolid | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–>8 | 99.1/0.9 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 2 | 0.5–4 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Teicoplanin | ≤2 | 8 | ≤2–>16 | 100.0/0.0 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–1 | 100.0/— |

| Erythromycin | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 20.0/77.0 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | >2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 58.6/39.6 |

| Tetracycline | 1 | >8 | ≤0.5–>8 | 81.2/16.8 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 | >8 | ≤1–>8 | 70.9/23.4 |

| Levofloxacin | 4 | >4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 42.2/56.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | >4 | >4 | 0.06–>4 | 41.8/57.3 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 1 | >4 | ≤0.5–>4 | 65.0/35.0 |

| Enterococcus spp.e (855) | ||||

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | 0.25–8 | 99.3/0.1 |

| Ampicillin | 1 | >8 | ≤0.25–>8 | 74.9/25.1 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | >16 | 0.25–>16 | 78.4//21.3 |

| Teicoplanin | ≤2 | >16 | ≤2–>16 | 79.9/18.5 |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 2 | ≤0.06–8 | 99.8/— |

| Erythromycin | >16 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 5.5/60.2 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 100.0/— |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | >4 | ≤0.12–>4 | 54.9/43.7 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2 | >4 | ≤0.03–>4 | 46.3/45.8 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (874) | ||||

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | ≤0.12–2 | 100.0/— |

| Penicillinf | ≤0.06 | 2 | ≤0.06–8 | 93.6/0.6 |

| Penicilling | ≤0.06 | 2 | ≤0.06–8 | 58.5/13.7 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | ≤1 | 4 | ≤1–>8 | 88.8/6.8 |

| Ceftriaxoneh | ≤0.06 | 1 | ≤0.06–8 | 92.8/1.4 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 53.5/45.9 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | >2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 82.0/17.2 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 1 | 0.25–>4 | 98.2/1.5 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5 | >8 | ≤0.5–>8 | 76.2/23.3 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.03 | 0.03 | ≤0.015–0.06 | 100.0/— |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤0.5 | >4 | ≤0.5–>4 | 70.0/18.8 |

| Viridans group and other streptococcii (359) | ||||

| Linezolid | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.12–1 | 100.0/— |

| Penicillin | ≤0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–8 | 81.3/1.4 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–8 | 96.7/1.4 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–1 | 100.0/— |

| Daptomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.06–1 | 100.0/— |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12 | 8 | ≤0.12–>16 | 53.6/42.5 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | >2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 88.3/10.9 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 2 | ≤0.12–>4 | 92.8/6.7 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5 | >8 | ≤0.5–>8 | 62.0/33.5 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 100.0/— |

| Beta-hemolytic streptococcij (874) | ||||

| Linezolid | 1 | 1 | 0.25–1 | 100.0/— |

| Penicillin | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06–0.12 | 100.0/— |

| Ceftriaxone | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Vancomycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Daptomycin | 0.12 | 0.25 | ≤0.06–0.5 | 100.0/— |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12 | >16 | ≤0.12–>16 | 62.4/36.2 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25 | >2 | ≤0.25–>2 | 78.4/20.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.12–>4 | 99.4/0.6 |

| Tetracycline | 8 | >8 | ≤0.5–>8 | 48.1/50.9 |

| Tigecyclineb | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.12 | 100.0/— |

Criteria as published by the CLSI (21). β-Lactam susceptibility should be directed by the oxacillin test results. —, no interpretive criteria are available for resistant category.

FDA breakpoints were applied when available (Tygacil product insert, 2010; Pfizer, Inc.).

Organisms include Staphylococcus auricularis (1), Staphylococcus capitis (34), Staphylococcus schleiferi (1), Staphylococcus caprae (4), Staphylococcus epidermidis (148), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (16), Staphylococcus hominis (31), Staphylococcus intermedius (1), Staphylococcus lugdunensis (84), Staphylococcus pettenkoferi (2), Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (3), Staphylococcus pseudintermedius/intermedius (3), Staphylococcus simulans (8), unspeciated Staphylococcus (1), and Staphylococcus warneri (3).

Organisms include Staphylococcus arlettae (1), Staphylococcus auricularis (2), Staphylococcus capitis (15), Staphylococcus cohnii (4), Staphylococcus caprae (1), Staphylococcus epidermidis (328), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (29), Staphylococcus hominis (32), Staphylococcus intermedius (2), Staphylococcus lentus (3), Staphylococcus lugdunensis (2), Staphylococcus pasteuri (1), Staphylococcus pettenkoferi (1), Staphylococcus pseudintermedius/intermedius (1), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (10), Staphylococcus sciuri (1), Staphylococcus simulans (12), Staphylococcus condimenti (1), Staphylococcus warneri (10), and Staphylococcus xylosus (1).

Organisms include Enterococcus avium (4), E. casseliflavus (6), E. durans (1), E. faecalis (589), E. faecium (239), E. gallinarum (8), E. hirae (5), and E. raffinosus (3).

Criteria as published by the CLSI (21) for parenteral penicillin (non-meningitis).

Criteria as published by the CLSI (21) for penicillin (oral penicillin V).

Criteria as published by the CLSI (21) for non-meningitis.

Organisms include Streptococcus australis (3), Streptococcus canis (7), Streptococcus constellatus (35), Streptococcus cristatus (3), Streptococcus gallolyticus (10), Streptococcus gordonii (13), Streptococcus lutetiensis (3), Streptococcus anginosus group (27), Streptococcus mitis group (16), Streptococcus mitis/oralis (49), Streptococcus mutans (4), Streptococcus parasanguinis (28), Streptococcus salivarius group (10), Streptococcus salivarius (6), Streptococcus anginosus (62), Streptococcus bovis group (4), Streptococcus infantis (2), Streptococcus intermedius (7), Streptococcus mitis (9), Streptococcus oralis (49), Streptococcus sanguinis (10), and Streptococcus vestibularis (2).

Organisms include Streptococcus pyogenes (342), Streptococcus agalactiae (417), Streptococcus equi (1), Streptococcus pseudoporcinus (1), and Streptococcus dysgalactiae (113).

FIG 1.

MRSA and MSSA rate by year for the LEADER program.

The linezolid MIC50/90 for Staphylococcus aureus was 1/1 μg/ml (Table 2). The MIC50 and modal MIC for MRSA and MSSA were the same, at 1 μg/ml (Table 1 and 2). There were only two Staphylococcus aureus (both MRSA) strains that were resistant to linezolid, and one isolate had a MIC of 4 μg/ml (Table 3). Both resistant isolates were from Long Beach, CA. One harbored a G2576T ribosomal mutation only, while the other harbored multiple mechanisms, which were G2576T, the cfr methyltransferase, and alterations in L3 (Table 3). PFGE indicated that these two isolates were not related (SA468A and SA468B) (Table 3). The one MRSA isolate with a MIC of 4 μg/ml was from New Orleans, LA, and harbored cfr (Table 3). The overall linezolid resistance rate among Staphylococcus aureus isolates was only 0.10% (including the isolate with the elevated linezolid MIC of 4 μg/ml harboring cfr). This rate generally has been stable since 2007 (Table 4) (3–9).

TABLE 2.

Cumulative frequency of isolates inhibited at each linezolid MIC for six different groups of Gram-positive cocci isolated from all U.S. census regions (n = 6,865 strains)

| Organism group (no. tested) | Percent of isolates inhibited at linezolid MIC (μg/ml) of: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | >8 | |

| Beta-hemolytic streptococci (874) | 0.0 | 1.8 | 49.3 | 100.0 | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (874) | 0.3 | 3.5 | 36.6 | 99.7 | 100.0 | |||

| Enterococci (855) | 0.0 | 0.8 | 20.4 | 95.2 | 99.3 | 99.9a | 100.0 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (3,106) | 0.0 | 0.7 | 30.4 | 99.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 | >99.9 | 100.0b |

| MRSA (1,465) | 0.0 | 1.0 | 35.0 | 99.2 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 |

| MSSA (1,641) | 0.0 | 0.5 | 26.3 | 98.8 | 100.0 | |||

| Viridans group streptococci (359) | 0.8 | 7.0 | 65.2 | 100.0 | ||||

| CoNSd (797) | 0.6 | 28.2 | 94.0 | 99.2 | 99.2 | 99.4c | 99.4 | 100.0 |

| MRCoNS (457) | 0.4 | 26.5 | 93.2 | 98.9 | 98.9 | 99.1c | 99.1 | 100.0 |

| MSCoNS (340) | 0.9 | 30.5 | 95.0 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 100.0 |

Four of these strains had MICs of ≥8 μg/ml when tested using reference frozen-form MIC panels.

One isolate with a MIC of >8 μg/ml.

This strain had a MIC of 8 μg/ml when tested using reference frozen-form MIC panels.

MRCoNS, methicillin-resistant CoNS; MSCoNS, methicillin-susceptible CoNS.

TABLE 3.

Isolates with elevated or resistance-level linezolid MICs (≥4 μg/ml) in the 2014 LEADER program

| Organism | City | State | Age (yr)/sexd | Linezolid MIC (μg/ml) | Resistance mechanism(s) | PFGEa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Long Beach | CA | 21/F | 8 | G2576T | SA468A |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Long Beach | CA | 23/M | 16 | cfr, G2576T, L3 (H146 deletion, P151L) | SA468B |

| Staphylococcus aureus | New Orleans | LA | 54/F | 4 | cfr | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Houston | TX | 39/M | 64 | G2576T, L3 (G137S, H146P, M156T), L4 (71G72 insertion) | SEPI116Db |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Houston | TX | 68/M | 128 | cfr, L3 (H146Q, V154L, A157R), L4 (71G72 insertion) | SEPI116Eb |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Long Beach | CA | 80/F | 128 | cfr, L3 (G137S, H146Q, V154L, A157R), L4 (71G72 insertion) | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | San Francisco | CA | 52/M | >128 | cfr, L3 (H146Q, V154L, A157R), L4 (71G72 insertion) | SEPI470A |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Memphis | TN | NA | >128 | cfr, G2576T, L4 (G137S, H146P, F147Y, M156T), L4 (71G72 insertion) | |

| Staphylococcus hominis | Seattle | WA | 38/F | 8 | cfr, L3 (M169L) | |

| E. faecium | Charlottesville | VA | 42/M | 4 | G2576T | |

| E. faecium | Fairbanks | AK | 62/M | 8 | G2576T | EFM461A |

| E. faecium | Fairbanks | AK | 62/M | 8 | G2576T | EFM461A1 |

| E. faecium | Los Angeles | CA | 34/M | 16 | G2576T | EFM467Bc |

| E. faecium | Atlanta | GA | 6/M | 8 | cfr, G2576T | |

| E. faecalis | Burlington | VT | 58/F | 8 | optrA |

The PFGE profile pattern nomenclature consists of three types of information. PFGE type was assigned according to the isolate code (initials representing the organism; e.g., Staphylococcus aureus is SA), site identifier (internal JMI institution number), and a capital letter for the PFGE group.

One isolate each (from 2011) displayed the same SEPI116D and SEPI116E patterns as the isolates from 2014.

PFGE profile distinct from the one noted for nonsusceptible isolates detected from this site during the 2013 (EFM467A) LEADER program.

F, female; M, male.

TABLE 4.

Eleven-year trend in linezolid resistance rates observed in the LEADER program (2004 to 2014)

| Organism (no. tested) | % Linezolid nonsusceptible or resistanta |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (33,788) | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| CoNSb (8,361) | 0.20 | 1.13 | 1.61 | 1.76 | 1.64 | 1.47 | 1.48 | 1.18 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.75 |

| Enterococci (9,387) | 0.80 | 0.64 | 1.83 | 1.13 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.12 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (8,466) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| VGSc (3,139) | NT | NT | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| BHSd (5,818) | NT | NT | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| All organisms (68,959) | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

Activity of linezolid against CoNS.

All CoNS were susceptible to vancomycin, tigecycline, and teicoplanin (Table 1). Linezolid and daptomycin also exhibited a high level of activity against CoNS, with susceptibility ranging from 99.1% (linezolid; methicillin-resistant CoNS) to 100.0% (daptomycin; methicillin-resistant CoNS) (Table 1). Linezolid potency was not adversely influenced by oxacillin susceptibility or resistance (Table 2). The MIC50/90 values were 0.5/0.5 μg/ml, respectively, and the overall linezolid susceptibility rate was 99.2% (Table 1 and data not shown).

Susceptibility rates for erythromycin, the fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, tetracycline, and gentamicin were lower for methicillin-resistant CoNS than for methicillin-susceptible CoNS (Table 1). For example, susceptibility to erythromycin was 20.0% for MRCoNS and 64.7% for MSCoNS (Table 1). Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin ranged from 41.8 to 42.2% for MRCoNS and 85.0% for MSCoNS (Table 1). The overall oxacillin-resistant CoNS rate was 57.3% (Table 1). The oxacillin-resistant rates varied by U.S. Census Bureau region (49.4 to 68.5%), with the highest rate detected in the east south central region (data not shown).

Six CoNS isolates demonstrated linezolid MIC results of ≥4 μg/ml (Table 3). Five were identified as Staphylococcus epidermidis, which originated from three states: Texas (2 isolates), California (2 isolates), and Tennessee (1 isolate). For the Texas isolates, one isolate each displayed the same PFGE patterns (SEPI116D and SEPI116E) as isolates from 2011 (7). All but one linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis isolate contained cfr in addition to the presence of mutations in the ribosomal proteins L3 and L4, alone or in combination with 23S rRNA (G2576T) mutations (Table 3). MIC values for these isolates were high, ranging from 64 to >128 μg/ml. The linezolid-resistant CoNS isolate which exhibited the lowest MIC value (4 to 8 μg/ml; Staphylococcus hominis from Seattle, WA) displayed a cfr and a ribosomal protein mutation (L3) (Table 3).

Activity of linezolid tested against enterococci.

A total of 855 enterococci were tested, of which 68.9% were Enterococcus faecalis and 28.0% E. faecium (Table 1). The ampicillin susceptibility rate was 74.9% and the vancomycin resistance (VRE) rate was 21.3% (Table 1). VRE rates varied by U.S. Census Bureau region, ranging from 8.4% (west north central) to 30.3% (south Atlantic). Ampicillin resistance in the enterococci was due primarily to E. faecium (90.0% resistance; data not shown). No E. faecalis isolates were ampicillin resistant. The VanA resistance phenotype represented 92.6% of the VRE. Linezolid, daptomycin, and tigecycline were the most active agents tested against enterococci, with susceptibility rates of 99.3, 99.8, and 100.0%, respectively (Table 1).

One E. faecalis and five E. faecium (≥4 μg/ml) isolates exhibited nonsusceptible linezolid MIC results. These strains were found in Alaska (2 isolates), California (1 isolate), Georgia (1 isolate), Virginia (1 isolate), and Vermont (1 isolate) (Table 3). All E. faecium nonsusceptible strains had G2576T mutations, and one isolate also harbored cfr (E. faecium from Atlanta, GA; MIC ranged from 4 to 8 μg/ml). The E. faecium isolate from Los Angeles displayed a distinct PFGE profile different from that of a nonsusceptible isolate recovered there during 2013 (9). One E. faecalis isolate harbored the optrA gene.

Activity of linezolid tested against Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Linezolid was active against Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC50 and MIC90, 1 μg/ml; 100.0% susceptible), with only 0.3% of strains at a MIC of 2 μg/ml (susceptible breakpoint) (Tables 1 and 2). Vancomycin (100.0% susceptible; MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml), tigecycline (100.0% susceptible; MIC90, 0.03 μg/ml), and levofloxacin (98.2% susceptible; MIC90, 1 μg/ml) were highly active against the pneumococci (Table 1). Penicillin nonsusceptibility (MIC, ≥0.12 μg/ml; oral penicillin V breakpoint) occurred at a rate of 41.5%, and erythromycin resistance (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml) occurred at 45.9% (Table 1). Susceptibility rates of the most active β-lactams ranged from 88.8% (amoxicillin-clavulanate) to 93.6% (penicillin at ≤2 μg/ml; penicillin parenteral [non-meningitis] breakpoint); ceftriaxone susceptibility was 92.8% (Table 1).

Levofloxacin resistance, at 1.5% in 2014 (MIC, ≥8 μg/ml), ranged from 0.0% (Pacific region) to 4.5% in New England (data not shown). The east north central region was the only other region with a levofloxacin resistance rate over 2.0% (2.1%).

Activity of linezolid tested against viridans group streptococci, beta-hemolytic streptococci, and other streptococci.

The viridans group streptococci were highly susceptible to linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, and tigecycline (all strains were 100.0% susceptible) (Table 1). The susceptibility of the viridans group streptococci was reduced for erythromycin (53.6%), tetracycline (62.0%), and penicillin (81.3%) (Table 1). Clindamycin susceptibility was at 88.3%, and levofloxacin nonsusceptibility was 7.2% (0.6%; intermediate category; Table 1). Linezolid MICs among the viridans group streptococci were predominantly at 0.5 to 1 μg/ml (MIC50/90, 0.5/1 μg/ml), and no isolate exhibited a linezolid MIC at the susceptible breakpoint of 2 μg/ml (Table 2).

A total of 874 beta-hemolytic streptococci, 39.1% of which were Streptococcus pyogenes and 47.7% of which were Streptococcus agalactiae, were tested (Table 1). High rates of resistance occurred for erythromycin (36.2%), clindamycin (20.5%), and tetracycline (50.9%) (Table 1). Macrolide resistance varied by region, from a low of 29.1% (south Atlantic) to a high of 51.2% (east south central) (data not shown). Linezolid, tigecycline, daptomycin, penicillin, ceftriaxone, and vancomycin inhibited all beta-hemolytic streptococci tested at their susceptible breakpoints (Table 1). Susceptibility to levofloxacin was 99.4% (Table 1). The linezolid MIC range was 0.25 to 1 μg/ml, with 47.5% of isolates at 0.5 μg/ml and 50.7% at 1 μg/ml (Table 2). No isolates exhibited a linezolid MIC value at or above the breakpoint concentration of 2 μg/ml (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Linezolid susceptibility testing of >6,000 Gram-positive pathogens demonstrated excellent activity and a sustained susceptibility rate of 99.78% overall (99.62 to 99.83% during 2008 to 2013). Linezolid MIC population distributions have remained stable without evidence of “MIC creep” among all monitored species (3–9). Against Staphylococcus aureus, the key resistance finding was that the MRSA rate was 47.2% (47.9% in 2013). This represents an 11.0% decrease since 2007 (3–9). In LEADER 2014, three linezolid-resistant MRSA isolates (including one isolate with a MIC at 4 μg/ml with a confirmed resistance mechanism, cfr) from two census regions were detected. One MRSA isolate harbored cfr only (MIC, 4 μg/ml), one harbored G2576T only (MIC, 8 μg/ml), and one contained cfr and G2576T with L3 changes (MIC, ≥8 μg/ml).

Inducible clindamycin resistance among erythromycin-resistant, clindamycin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains was 21.1% overall but was decreased compared to rates in previous years (3–9). Overall clindamycin resistance remained high. Among erythromycin-resistant, clindamycin-susceptible strains, the highest rate of inducible clindamycin resistance (44.4%) was in New England, as was the case in previous years (44.4% in 2013, 47.0% in 2012, and 44.8% in 2011) (7–9).

In the 2014 program, nonsusceptibility to linezolid occurred among the enterococci (0.70%; five E. faecium and one E. faecalis strain) and six CoNS (0.75%; five Staphylococcus epidermidis with MIC of ≥8 μg/ml and one Staphylococcus hominis with a MIC of 8 μg/ml and containing a cfr and L3 mutation). Each of two linezolid-nonsusceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from Houston displayed the same PFGE patterns as previous isolates from 2011 (SEPI116D and SEPI116E PFGE, respectively) (7).

Overall, there were 15 nonsusceptible isolates, 8 of which (53.3%) harbored a cfr gene. During the previous LEADER program years 2011 through 2013, the percentage of linezolid-nonsusceptible isolates harboring cfr ranged from 13 to 25% (7–9). As cfr confers resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, its presence limits the potential use of other agents (18, 19, 24). This increase in the presence of cfr in the linezolid-nonsusceptible isolates is concerning and deserves watching in next year's LEADER surveillance, especially considering the fact that cfr may be transmissible due to its mobile nature (18, 19, 24). In spite of this, the “all-organism” linezolid-resistant and -nonsusceptible rate (0.22%) is essentially the same as that in 2005 (0.24%), with variation from 0.14 to 0.45% over any 1-year period (1, 3–9, 27).

Resistance to other highly active anti-Gram-positive agents has emerged over the years during this program but also generally remains low, such as daptomycin nonsusceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus (0.1% in 2014, no isolates in 2011 and 2013, and 0.1% in 2012), enterococci (0.2% in 2014, 0.1% in 2011 and 2013, and no isolates in 2012), and viridans group streptococci (no isolates in 2014 and 2012, 0.2% in 2011, and 0.3% in 2013) (7–9). Teicoplanin-intermediate and -resistant CoNS were at 10.9% in 2014 (EUCAST criteria), 14.0% in 2013, 13.7% in 2012, and 10.8% in 2011 (7–9). Vancomycin-intermediate strains of Staphylococcus aureus and CoNS were not identified in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014 (<0.1 to 0.2% in 2010) (6–9). Levels of levofloxacin-resistant streptococci were highest among viridans group streptococci (6.7% in 2014, 4.5% in 2013, 5.7% in 2012, and 7.7% in 2011) and recently have been increasing in other streptococci worldwide (7–9). VRE and MRSA rates remain high but overall have consistently declined for some time (6–9).

Treatment options for infections due to multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens are limited; however, linezolid continues to demonstrate excellent in vitro activity against these organisms. Molecular epidemiology and the testing of mechanisms of resistance (various target mutations, optrA, or cfr) for the linezolid-resistant strains indicate endemic/epidemic clonal dissemination in a number of monitored medical centers over several years. All linezolid-nonsusceptible strains had detectable resistance mechanisms, sometimes several. As in earlier reports, linezolid resistance in the United States among Gram-positive pathogens remains significantly below 1.0% (the actual rate for 2014 was 0.22%). Expanded molecular processing of oxazolidinone resistance mechanisms has widened our understanding of the ribosomal targets and mutations necessary to elevate oxazolidinone MICs beyond or at the limit of the wild-type range (4 μg/ml).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express appreciation to the following persons for their contributions to the manuscript: Mike Janechek, P. R. Rhomberg, and M. Castanheira.

All coauthors are employees of JMI Laboratories except for P. A. Hogan, who is an employee of Pfizer, Inc. JMI Laboratories received funding for this study from Pfizer, Inc., in connection with the development of the manuscript. This study was supported by Pfizer, Inc., via the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program platform.

JMI Laboratories, Inc., also has received research and educational grants in 2014 to 2015 from Achaogen, Actavis, Actelion, Allergan, American Proficiency Institute (API), AmpliPhi, Anacor, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Basilea, Bayer, BD, Cardeas, Cellceutix, CEM-102 Pharmaceuticals, Cempra, Cerexa, Cidara, Cormedix, Cubist, Debiopharm, Dipexium, Dong Wha, Durata, Enteris, Exela, Forest Research Institute, Furiex, Genentech, GSK, Helperby, ICPD, Janssen, Lannett, Longitude, Medpace, Meiji Seika Kasha, Melinta, Merck, Motif, Nabriva, Novartis, Paratek, Pfizer, Pocared, PTC Therapeutics, Rempex, Roche, Salvat, Scynexis, Seachaid, Shionogi, Tetraphase, The Medicines Co., Theravance, ThermoFisher, VenatoRX, Vertex, Wockhardt, Zavante, and some other corporations. Some JMI employees are advisors/consultants for Allergan, Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer, Cempra, and Theravance.

We have no speakers bureaus and stock options to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Draghi DC, Sheehan DJ, Hogan P, Sahm DF. 2005. In vitro activity of linezolid against key gram-positive organisms isolated in the United States: results of the LEADER 2004 surveillance program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:5024–5032. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5024-5032.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draghi DC, Sheehan DF, Hogan P, Sahm DF. 2006. Current antimicrobial resistance profiles among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus encountered in the outpatient setting. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 55:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones RN, Ross JE, Castanheira M, Mendes RE. 2008. United States resistance surveillance results for linezolid (LEADER Program for 2007). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 62:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell DJ, Mendes RE, Ross JE, Jones RN. 2009. Linezolid surveillance program results for 2008 (LEADER Program for 2008). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 65:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrell DJ, Mendes RE, Ross JE, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2011. LEADER Program results for 2009: an activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using 6,414 clinical isolates from the United States (56 medical centers). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3684–3690. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01729-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Mendes RE, Ross JE, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2012. LEADER surveillance program results for 2010: an activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using 6801 clinical isolates from the United States (61 medical centers). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 74:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Ross JE, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2013. Linezolid surveillance results for the United States: LEADER surveillance program 2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1077–1081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02112-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendes RE, Flamm RK, Hogan PA, Ross JE, Jones RN. 2014. Summary of linezolid activity and resistance mechanisms detected during the 2012 LEADER surveillance program for the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1243–1247. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02112-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Hogan PA, Ross JE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2015. In vitro activity of linezolid as assessed through the 2013 LEADER surveillance program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinabarger D. 1999. Mechanism of action of the oxazolidinone antibacterial agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 8:1195–1202. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.8.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford CW, Zurenko GE, Barbachyn MR. 2001. The discovery of linezolid, the first oxazolidinone antibacterial agent. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord 1:181–199. doi: 10.2174/1568005014606099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diekema DJ, Jones RN. 2001. Oxazolidinone antibiotics. Lancet 358:1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ippolito JA, Kanyo ZF, Wang D, Franceschi FJ, Moore PB, Steitz TA, Duffy EM. 2008. Crystal structure of the oxazolidinone antibiotic linezolid bound to the 50S ribosomal subunit. J Med Chem 51:3353–3356. doi: 10.1021/jm800379d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzales RD, Schreckenberger PC, Graham MB, Kelkar S, DenBesten K, Quinn JP. 2001. Infections due to vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium resistant to linezolid. Lancet 357:1179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutnick AH, Enne V, Jones RN. 2003. Linezolid resistance since 2001: SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Ann Pharmacother 37:769–774. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Castanheira M, DiPersio J, Saubolle MA, Jones RN. 2008. First report of cfr-mediated resistance to linezolid in human staphylococcal clinical isolates recovered in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2244–2246. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00231-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toh SM, Xiong L, Arias CA, Villegas MV, Lolans K, Quinn J, Mankin AS. 2007. Acquisition of a natural resistance gene renders a clinical strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to the synthetic antibiotic linezolid. Mol Microbiol 64:1506–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long KS, Poehlsgaard J, Kehrenberg C, Schwarz S, Vester B. 2006. The cfr rRNA methyltransferase confers resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2500–2505. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00131-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonilla H, Huband MD, Seidel J, Schmidt H, Lescoe M, McCurdy SP, Lemmon MM, Brennan LA, Tait-Kamradt A, Puzniak L, Quinn JP. 2010. Multicity outbreak of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis associated with clonal spread of a cfr-containing strain. Clin Infect Dis 51:796–800. doi: 10.1086/656281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. M07-A10. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 10th ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. M100-S25. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 25th informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. M02-A12. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; 12th ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Farrell DJ, Spanu T, Fadda G, Jones RN. 2010. Assessment of linezolid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus epidermidis causing bacteraemia in Rome, Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2329–2335. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz L, Kiratisin P, Mendes R, Panesso D, Singh KV, Arias CA. 2012. Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to linezolid due to cfr in a human clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3917–3922. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Kim J, Myers D, Ross JE, Jones RN. 2012. Streptococcus sanguinis displaying a cross resistance phenotype to several ribosomal RNA targeting agents, including linezolid. Abstr 52nd Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, abstr C1-1343. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Lv Y, Cai J, Schwarz S, Cui L, Hu Z, Zhang R, Li J, Zhao Q, He T, Wang D, Wang Z, Shen Y, Li Y, Feßler AT, Wu C, Yu H, Deng X, Xia X, Shen J. 2015. A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2182–2190. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pillar CM, Draghi DC, Sheehan DJ, Sahm DF. 2008. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: findings of the stratified analysis of the 2004 to 2005 LEADER surveillance programs. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 60:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]