Abstract

Transgender women bear a disproportionate burden of HIV, yet data among this population are not routinely collected in HIV clinical cohorts. Brief surveys and follow-up qualitative interviews were conducted with principal investigators or designated representatives of 17 HIV clinical cohorts to determine the acceptability and feasibility of pooling transgender-specific data from existing HIV clinical cohort studies. Twelve of 17 sites reported that they already collect gender identity data but not consistently. Others were receptive to collecting this information. Many also expressed interest in a study of clinical outcomes among HIV-infected transgender women using pooled data across cohorts. The collection of longitudinal data on transgender people living with HIV is acceptable and feasible for most North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) cohorts. HIV clinical cohort studies should make efforts to include transgender individuals and develop the tools to collect quality data on this high-need population.

It has been estimated that approximately 700,000 individuals in the United States identify as transgender,1 with a recent meta-analysis reporting an HIV prevalence of 21.7% among transgender women (natal males with female gender identity).2 This population experiences high levels of stigma, violence, depression, sex work, and substance use that make them particularly vulnerable to HIV infection.3 Recent evidence from cross-sectional and qualitative studies suggests disparities in engagement and retention in care among transgender women compared to other people living with HIV.4 However, data on clinical outcomes among the HIV-infected transgender women are very limited.5 Without additional data, important questions such as whether the above-mentioned social factors or the long-term concurrent use of feminizing hormones and antiretroviral therapy affect HIV disease progression, metabolic function, and cardiovascular health remain unanswered. Moreover, opportunities to better understand gendered disparities in HIV outcomes are missed. For example, previous cohort studies have demonstrated that nontransgender women have lower initial HIV viral loads than nontransgender men, yet their rate of disease progression is the same.6 Longitudinal data among HIV-infected transgender adults taking hormone therapy could shed some light on potential mechanisms for these gender differences.

Cohort studies of people with HIV infection are well-suited for examination of longitudinal outcomes in specialized populations, owing to their ability to collect standardized data on health behaviors, clinical markers, and outcomes with minimal attrition. The power of cohort studies to advance HIV science is evidenced by the long-running Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study among gay men,7 which has led to remarkable breakthroughs such as the validation of viral load as a key marker of HIV disease progression8 and the discovery of the CCR5 receptor on CD4 cells,9 and inspired the creation of the Women's Interagency HIV Study in 1993.10

Many existing research cohorts of HIV-infected patients seen in clinical settings likely already enroll some transgender individuals. However, little information is known about whether these studies collect data on gender identity, and if so, how systematically it is collected. To better understand the ability and interest of existing cohorts in collecting this information, we contacted 17 HIV clinical cohorts who contribute to the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), the largest HIV cohort collaboration in North America.11 This consortium includes more than 20 interval and clinical HIV cohorts in the United States and Canada, contributing data on more than 130,000 people living with HIV. Currently, transgender individuals are excluded from enrollment in the study consortium.

We emailed a brief two-question survey to principal investigators or designated representatives of the 17 NA-ACCORD clinical cohorts. The first question asked “Do you routinely collect transgender status in your clinical cohort?” If the answer was “no,” they were asked “Are you interested in collecting this data, if you were provided support for ways to collect transgender status?” If the answer was “yes,” they were asked if they were willing to have a brief qualitative telephone interview. Subsequent telephone interviews lasted approximately 15 min and included a discussion of how data on gender identity were collected, the approximate number of transgender people in the cohort, and any interest in future transgender-specific studies.

All 17 clinical HIV cohorts agreed to participate. Of these cohorts, 13 were based in the United States and four were based in Canada; 11 were based at single sites, whereas six were multicenter studies. Among the 17 cohorts, 12 (71%) routinely gather data on gender identity, including all four of the Canadian cohorts. The manner of data collection varies. Of those who gather these data, two (17%) use the electronic medical record (EMR) to identify diagnosis codes for “Gender identity disorder in adolescents or adults” (ICD-9 code 302.85) and to compare natal sex with reports of feminizing hormones from medication lists. Four sites (33%) ask specific questions about gender identity at intake. The remaining six cohorts (50%) rely on the medical provider to record this information in the participant's record. Methods for determining transgender status included (1) specifically asking if the participant is transgender, (2) using a two-step method comparing natal sex to participant-reported current gender identity, and (3) unspecified provider assessment.

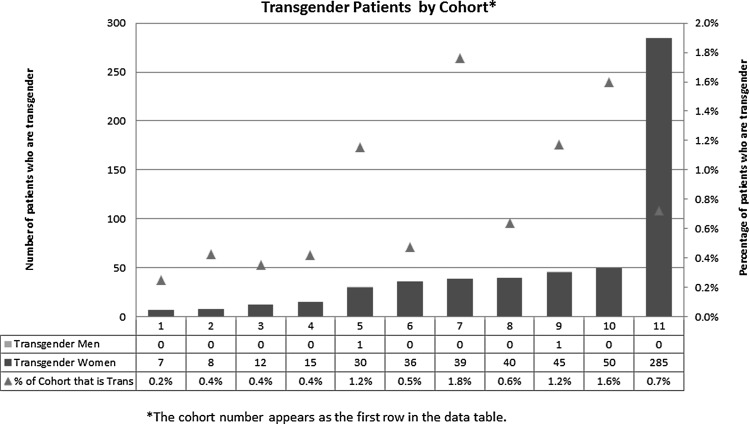

A total of 569 transgender participants (567 transgender women and two transgender men) were reported by the 11 cohorts that were able to provide an estimate (Fig. 1), representing approximately 0.8% of the HIV-infected population under study (range by cohort: 7 to 285). Most principal investigators (n=15, 88%) reported that they would be willing to gather further data systematically and participate in relevant studies on transgender women with HIV. It is notable that 88% of cohorts would be willing to collect these data for use in transgender-specific research, even though only 71% collect it currently. These findings suggest that routine data collection on transgender people with HIV is not only possible but desirable in HIV clinical cohort studies that rely on EMR data and more traditional methods of data collection. Furthermore, standardized methods of collecting data across cohorts to make information comparable are acceptable to these cohorts.

FIG. 1.

Transgender patients by cohort.

Given the relatively few transgender individuals enrolled at any one site and the variability in numbers across sites, our study also suggests that pooling data across studies (such as via cohort collaborations like the NA-ACCORD) may be an efficient way to obtain the sample size required to adequately answer questions of clinical importance in this patient population. We acknowledge that some research questions may require a cohort exclusively composed of transgender individuals, while others may need a nontransgender comparison population. Cohorts that already collect information on nontransgender individuals with HIV infection are well-suited for questions of the latter variety, and it has been noted that matched-pair studies nested within larger clinical cohorts may further improve the efficiency of transgender health research.12 Furthermore, pooling resources across a broad geographic range (e.g., at the national or regional level) can help to overcome the limited generalizability of some prior transgender health studies that are specific to localized urban settings. However, pooling data may limit the examination of site-specific factors that may play a role in care engagement and positive clinical outcomes in transgender participants.

In addition to systematically identifying transgender individuals, we also recommend that questions asked of transgender individuals in clinical HIV cohorts be expanded to include topics of clinical relevance to transgender health, such as type and duration of hormone use, injectable silicone use, and related long-term clinical outcomes. Longitudinal studies that collect time-updated data on exposure variables are particularly well-suited to answer these nuanced clinical questions. In addition to prospectively measured outcomes, linkages with hospitalization and vital statistics data (e.g., the National Death Index) allow such studies to maximize completeness of outcome ascertainment.

In summary, we found that most principal investigators of established HIV clinical cohort studies in North America that we queried were willing to conduct or participate in research on transgender health. We encourage both individual studies and large-scale cohort collaborations to make efforts to include transgender individuals and develop the tools to collect quality data on this high-need patient population. In this way critical unanswered research questions can be addressed within current cohort infrastructures without the time and expense needed to create new ones. Resources containing standardized questions to assess transgender identity are available and could be routinely incorporated into data collection procedures.13 Collection of longitudinal data on transgender people living with HIV is acceptable and feasible for most North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) cohorts. HIV clinical cohort studies should make efforts to include transgender individuals and develop the tools to collect quality data on this high-need population.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gates GJ: How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender?: The Williams Institute, 2011. [updated April; cited November 14, 2014]. Available from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, et al. : Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13(3):214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan J, Kuhns LM, Johnson AK, et al. : Syndemic theory and HIV-related risk among young transgender women: The role of multiple, co-occurring health problems and social marginalization. Am J Public Health 2012;102(9):1751–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, and Johnson MO: Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med 2014;47(1):5–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Moore RD, and Gebo KA: Retention in care and health outcomes of transgender persons living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(5):774–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farzadegan H, Hoover DR, Astemborski J, et al. : Sex differences in HIV-1 viral load and progression to AIDS. Lancet 1998;352(9139):1510–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, et al. : The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol 1987;126(2):310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellors JW, Rinaldo CR, Jr, Gupta P, et al. : Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science (New York, NY) 1996;272(5265):1167–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, et al. : Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science (New York, NY) 1996;273(5283):1856–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacon MC, Wyl Vv, Alden C, et al. : The Women's Interagency HIV Study: An observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005;12(9):1013–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS, et al. : Cohort profile: The North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol 2007;36(2):294–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reisner SL, White JM, Bradford JB, and Mimiaga MJ: Transgender health disparities: Comparing full cohort and nested matched-pair study designs in a community health center. LGBT Health 2014;1(3):177–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The GenIUSS Group: Gender-Related Measures Overview: The Williams Institute, 2013. [cited November 14, 2014]. Available from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/GenIUSS-Gender-related-Question-Overview.pdf. [Google Scholar]