Abstract

Objective: Mammography is the most effective method to detect breast cancer in its earliest stages, reducing the risk of breast cancer death. We investigated the relationship between accessibility of mammography services at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) of breast cancer in each county in the United States.

Methods: County-level breast cancer mortality and incidence rates in 2006–2010 were used to estimate MIRs. We compared breast cancer MIRs based on the density and availability of FQHC delivery sites with or without mammography services both in the county and in the neighboring counties.

Results: The relationship between breast cancer MIRs and access to mammography services at FQHCs differed by race and county of residence. Breast cancer MIRs were lower in counties with mammography facilities or FQHC delivery sites than in counties without a mammography facility or FQHC delivery site. This trend was stronger in urban counties (p=0.01) and among whites (p=0.008). Counties with a high density of mammography facilities had lower breast cancer MIRs than other counties, specifically in urban counties (p=0.01) and among whites (p=0.01). Breast cancer MIR for blacks was the lowest in counties having mammography facilities; and was highest in counties without a mammography facility within the county or the neighboring counties (p=0.03).

Conclusions: Mammography services provided at FQHCs may have a positive impact on breast cancer MIRs. Expansion of services provided at the FQHCs and placement of FQHCs in additional underserved areas might help to reduce cancer disparities in the United States.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women, both in the United States (U.S.) and worldwide.1,2 The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that 231,840 women will have been diagnosed with breast cancer and 40,290 women will have died of the disease in 2015 in the U.S.3 Mammography is the single most effective method to detect breast cancer, and reduces breast cancer deaths by 20% to 31%.4–6 Thus ACS recommends an annual mammogram for women over 40 years of age,7 and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends a mammogram every other year for women aged 50 to 74 years.8 Early detection of breast cancer by mammography allows for the diagnosis of breast cancer in the early stages, resulting in less aggressive treatments and a higher probability of survival.

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are focused on improving primary care services and reducing health disparities for underserved rural and urban areas and racial/ethnic minorities. The number of FQHC sites and patients who visit FQHCs have increased exponentially in the past decade. The number of practice sites has increased by 55% since 2000 (from 730 in 2000 to 1,122 in 2011), while the number of patients has increased by 96% (from 10.3 million in 2001 to 20.2 million in 2011).9 As safety-net providers, FQHCs provide high-quality care to roughly 20.2 million Americans annually. These include vulnerable populations such as the poor, uninsured, publicly insured (e.g., Medicaid), and racial-ethnic minorities.9–12 In fact, uninsured and publicly insured Americans who visit FQHCs receive more preventive services, including mammograms and clinical breast examination, compared with those who do not visit FQHCs.13 Thus, the availability of FQHCs improves access to medical care for vulnerable populations.9

Breast cancer screening rates are strongly influenced by individual and regional-level socioeconomic status (SES).14–17 Women who have health insurance and a usual source of care are more likely to have a mammogram.14–17 Those who live in urban areas and areas where the average household income is >$60,000 per year have higher rates of mammography utilization within the preceding two years than those living in rural and poor areas.15 Women living in high-poverty areas are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at more advanced stages18–20 and to have lower survival rates.21 FQHCs can help to reduce disparities in accessing breast cancer screening services using a variety of strategies. Examples include providing mammography services directly to underserved populations and referring FQHC patients to other clinics.22 This may result in shortening wait times with concomitant earlier detection of breast cancer and improved survival. Unfortunately, low-income women from ethnic minority and underserved populations have to overcome multiple barriers to receive mammograms. The presence of mammography facilities, distance, and commute time to the facility, the neighborhood characteristics of the facility, and availability of public transportation are all factors that influence a woman's intention to be screened for breast cancer.14,23,24

The mortality to incidence ratio (MIR) statistic provides an alternative means to assess the burden of disease by presenting mortality after accounting for incidence. Traditional incidence and mortality statistics are expressed in terms of the total population in the region (derived from census data); however, only those individuals diagnosed with cancer will go on to die from their disease. Consequently, the mortality statistics do not accurately present the complete burden of disease, in particular, that experienced by certain minority populations (whose incidence rates may differ from the majority population).25 Moreover, the MIR statistic tells us about the virulence of disease in a population given a set incidence rate. The MIR statistic has been used to demonstrate racial disparities in cancers,25 as well as to examine the relationship between the health care system and cancer outcomes in the U.S.26,27 and worldwide.28

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between accessibility of FQHC mammography services and breast cancer MIR in each county in the U.S. We hypothesize that the increased availability of mammography services provided by FQHCs will be associated with improved survival and thus lower MIR statistics. In addition, this relationship may be mediated by location of the mammogram facility (urban, rural) and patients' race.

Methods

Data sources

We obtained age-adjusted breast cancer incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 populations for each U.S. county in 2006–2010 from the National Cancer Institute State Cancer Profile website.29 Race-specific incidence and mortality rates for whites and for blacks also were obtained. Rates were suppressed by the website when there were fewer than 3 incident cases of breast cancer or three breast cancer-related deaths per county. If counties have unknown or suppressed incidence and/or mortality information, those counties were excluded in the analysis. Cancer incidence or mortality data for Kansas, Minnesota, and Ohio could not be accessed because of state policies. Thus, counties located in these states also were excluded from the analysis. FQHC information was obtained from the Uniform Data System (UDS) from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA grantees, including FQHCs, are required to report their operation status through UDS every year. Assuming that the benefits of mammography services are not realized for several years,30 we opted to use data on mammography at FQHCs several years prior to our MIR period of 2006–2010. Thus, we chose FQHC data from the 1999 UDS. There were 690 FQHCs and 3,446 delivery sites in the UDS for 1999. FQHCs and their delivery sites that were located outside of the U.S. (e.g., Guam, Puerto Rico, etc.), and those did not have address information were excluded (27 FQHCs and 161 delivery sites). A total of 3,285 delivery sites of 663 FQHC grantees constituted the analytic sample. The data include each health center's activities, services offered, and patient demographic information (e.g., race/ethnicity). It also provides the number of encounters and number of users by several selected diagnoses and services, including mammography. FQHCs that recorded any patient encounters of mammography in 1999 were classified as mammography facilities at one more delivery sites. If the UDS record had no mammography patient encounters listed then the FQHC was classified as having no mammography facilities.

County-level SES information was obtained from the 2011–2012 Area Resource File.31 Urban/rural continuum of counties, percentage of persons over 25 years of age with more than a 4-year college degree, and percentage of families below poverty level in each county were considered county-level SES variables. Breast cancer incidence and mortality data, delivery site information, and county-level SES information were linked using state and county codes of the Federal Information Processing Standards, which comprises a standard set of geographic codes of all states and counties in the U.S. A total of 1,612 counties that had all information were included in the analysis.

Data mapping

Using ArcGIS® version 10.1 (ESRI, Redlands WA), FQHC delivery sites were mapped to examine the number of FQHC delivery sites and those of FQHC delivery sites that providing mammography services in 1999 in each county. The number of FQHC delivery sites and FQHC mammogram facilities were totaled for each county. Counties that share boundaries with each other were considered as neighboring counties. Based on the status of FQHC mammogram facilities and delivery sites both in the county and in neighboring counties, the availability of mammography services within the county was operationalized in three different ways. The first designation was: (1) having one or more mammography facilities; (2) not having a mammography facility; and (3) not having a FQHC delivery site. The second operationalization was: (1) having a high density of mammography facilities; (2) having a low density of mammography facilities; (3) not having an FQHC mammography facility; and (4) not having an FQHC delivery site. The last operationalization accounted for the existence of mammography facilities or FQHC delivery sites in neighboring counties such that counties were designated as: (1) having FQHC mammography facilities in the county (direct access); (2) having FQHC mammography facilities in neighboring counties (neighboring access); and (3) not having a mammogram facility in either the county or a neighboring county.

Statistical analysis

Breast cancer MIR in each county was calculated by dividing the mortality rate by the incidence rate. We have previously used this statistic to examine the impact of mortality after accounting for incidence.25 To examine mammography facilities' impact on breast cancer MIR, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to compare breast cancer MIRs across counties. The same analyses were repeated for strata defined by location of FQHC delivery sites (urban vs. rural). MIR's also were calculated and analyzed by race (i.e., Black and White, derived from the cancer statistic not the FQHC site). Too few counties had sufficient numbers of breast cancers for other minority groups to allow for conducting a meaningful analysis for other races. County-level SES indicators were adjusted in all models. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.3 (Cary, NC) with statistically significant two-sided alpha level <0.05.

Results

Among 1,612 counties, 590 (36.6%) had at least one FQHC delivery sites in 1999. Of those having at least one FQHC delivery site, 58.8% (n=347) provided mammography services. In looking at all counties, no significant differences were noted in MIR according to availability of FQHC mammography services (Table 1). Urban counties without a FQHC delivery site had the highest breast cancer MIR compared with counties that had FQHC delivery site (p=0.01). In contrast, no significant differences were noted for breast cancer MIR by existence of FQHC delivery sites and mammography services among rural counties (p=0.48). When stratified by race, MIRs for whites were significantly higher in counties without an FQHC delivery site (p=0.008); however, breast cancer MIRs for blacks in these same geographical areas did not manifest significant differences.

Table 1.

Adjusted Breast Cancer Mortality to Incidence Ratio by Existence of Federally Qualified Health Center Mammography Facilities

| FQHC mammography facilities | FQHC delivery site without mammography | No FQHC delivery site | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counties | ||||

| All | 0.200±0.003* | 0.202±0.003 | 0.208±0.002 | 0.06 |

| (n=347) | (n=243) | (n=1,022) | ||

| Urbana | 0.191±0.003 | 0.187±0.004* | 0.199±0.002 | 0.01 |

| (n=217) | (n=146) | (n=464) | ||

| Rurala | 0.211±0.006 | 0.221±0.006 | 0.218±0.003 | 0.48 |

| (n=130) | (n=97) | (n=558) | ||

| Population | ||||

| Whiteb | 0.193±0.003* | 0.193±0.004** | 0.202±0.002 | 0.008 |

| (n=309) | (n=221) | (n=936) | ||

| Blackb | 0.257±0.006*** | 0.280±0.008 | 0.265±0.007 | 0.08 |

| (n=135) | (n=75) | (n=100) | ||

Mortality to incidence ratio (MIR) adjusted for percentage of persons over 25 years of age with more than a 4-year college degree 2005–2009 and percentage of families below poverty level 2005–2009.

Urban/rural designation based upon county designation in area resources file.

MIRs for race derived from race-specific breast cancer incidence and mortality statistics.

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no federally qualified health center (FQHC) delivery site at p<0.10 (general linear model [GLM], Bonferroni test).

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no FQHC delivery site at p<0.05 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no FQHC mammogram facility at p<0.10 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

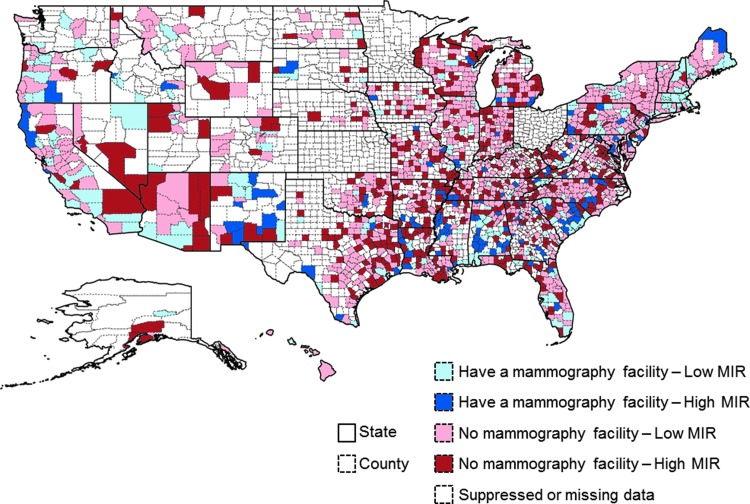

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the trends in mammography access and county MIRs. Of note, the northeastern and western regions of the country, along with some other key states such as Alabama and Florida, have clusters of high access and low MIR pairings. This map also highlights areas of significant need, particularly in states with large minority disparities (e.g., North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas).

FIG. 1.

Federally Qualified Health Centers concentration and breast cancer mortality to incidence ratios (MIRs).

In Table 2, the impact of mammography facility density is presented. The same trends noted for any FQHC mammography access also were found with FQHC mammography facility density. In general, counties with a high density of FQHC mammography facilities experienced the lowest breast cancer MIR for all counties, urban and rural counties, and for whites.

Table 2.

Adjusted Breast Cancer MIR by Number of FQHC Mammography Facilities and FQHC Delivery Sites in the County

| High-density FQHC mammography facilitiesa | Low-density FQHC mammography facilitiesb | No FQHC mammography facility | No FQHC delivery site | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counties | |||||

| All | 0.196±0.005 | 0.203±0.004 | 0.202±0.003 | 0.208±0.002 | 0.08 |

| (n=122) | (n=225) | (n=243) | (n=1,022) | ||

| Urbanc | 0.186±0.005 | 0.194±0.004 | 0.187±0.004** | 0.199±0.002 | 0.01 |

| (n=94) | (n=123) | (n=146) | (n=464) | ||

| Ruralc | 0.210±0.012 | 0.212±0.006 | 0.221±0.006 | 0.218±0.003 | 0.68 |

| (n=28) | (n=102) | (n=97) | (n=558) | ||

| Population | |||||

| Whited | 0.188±0.005* | 0.195±0.004 | 0.192±0.004** | 0.202±0.002 | 0.01 |

| (n=117) | (n=192) | (n=221) | (n=936) | ||

| Blackd | 0.263±0.009 | 0.252±0.008 | 0.280±0.008 | 0.265±0.007 | 0.13 |

| (n=60) | (n=75) | (n=75) | (n=100) | ||

MIR for percentage of persons over 25 years of age with more than a 4-year college degree 2005–2009 and percentage of families below poverty level 2005–2009.

More than two FQHC mammography facilities in the county.

One FQHC mammography facility in the county.

Urban/rural designation based upon county designation in area resources file.

MIRs for race derived from race-specific breast cancer incidence and mortality statistics.

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no FQHC delivery site at p<0.10 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no FQHC delivery site at p<0.05 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

Table 3 shows the relationship between breast cancer MIRs and existence of FQHC mammography facilities in the county and in the neighboring counties. Overall, breast cancer MIRs were the lowest in the counties having direct access to FQHC mammography services and were the highest in the counties having no access to FQHC mammography services. Breast cancer MIR for Blacks was significantly affected by access to mammography services (p=0.03).

Table 3.

Adjusted Breast Cancer MIR by Access to FQHC Mammography Facilities

| Direct access | Neighboring access | No access | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counties | ||||

| All | 0.200±0.003* | 0.205±0.002 | 0.209±0.002 | 0.07 |

| (n=347) | (n=629) | (n=636) | ||

| Urbana | 0.191±0.003 | 0.193±0.002 | 0.199±0.003 | 0.07 |

| (n=217) | (n=336) | (n=274) | ||

| Rurala | 0.211±0.006 | 0.216±0.004 | 0.220±0.003 | 0.38 |

| (n=130) | (n=293) | (n=362) | ||

| Population | ||||

| Whiteb | 0.193±0.003* | 0.199±0.002 | 0.202±0.002 | 0.07 |

| (n=309) | (n=570) | (n=587) | ||

| Blackb | 0.257±0.006** | 0.263±0.007 | 0.286±0.009 | 0.03 |

| (n=135) | (n=111) | (n=64) | ||

MIR for percentage of persons over 25 years of age with more than a 4-year college degree 2005–2009 and percentage of families below poverty level 2005–2009.

Urban/rural designation based upon county designation in area resources file.

MIRs for race derived from race-specific breast cancer incidence and mortality statistics.

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no access to FQHC mammography facility at p<0.10 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

Significantly different from MIR of counties having no access to FQHC mammography facility at p<0.05 (GLM, Bonferroni test).

Discussion

Findings from this ecological analysis demonstrated a significant relationship between FQHCs that provide breast cancer screenings and reduced breast cancer MIR. In addition, we observed statistically significant decreases in MIRs for counties with an FQHC (although no mammography services) in comparison to those without an FQHC. In the era of the Affordable Care Act and the “patient-centered medical home,” FQHCs are poised to intervene in the delivery of health services to underserved, rural, and minority populations. Our findings point to the potential to influence cancer outcomes, which is often considered to be outside the scope of services traditionally provided at FQHCs that tend to focus on providing primary care and chronic disease management. Indeed, the growth of mammography services offered within FQHCs increased by 2.5 times over the period available for analysis (322 FQHCs in 1999 to 787 FQHCs in 2012). Slightly over a third (34.3%) of FQHCs are still not able to offer mammography to their patients.

It is interesting that we observed the strongest associations in urban counties and in white populations. This suggests interesting avenues for further inquiry to better understand the mechanisms driving these trends. Among low-income Hispanic and African American women, Medicaid recipients, and uninsured patients, those who visit FQHCs have significantly higher rates of receiving a mammogram over the last 2 years compared with those who do not visit FQHCs.9

Although regular mammogram screening represents an effective method for reducing breast cancer mortality, several barriers hinder women from obtaining mammograms. Accessibility to mammography facilities, including distance and commute time to an existing mammography facility and available public transportation, is a potential geographic barrier to screening. Research shows that the odds of having a mammogram are greater among women living in areas with a high-density of mammography facilities14 and those with mammography facilities located near their homes.23 This may explain why we found evidence of a significant trend in urban counties versus rural counties. In addition, women living in areas with poor access to mammography facilities or even primary care physicians have a higher risk of being diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer.23,32 Moreover, poor access to primary care physicians is more strongly related to late-stage breast cancer in suburban and rural areas compared with urban areas.32

It is worth noting that differences in our MIR estimates may appear quite small at first glance in our tables. However, given the population scale of the estimates, these small differences can actually impact a large number of people. For instance, in a population of 1,000,000, the difference that was observed for white individuals (19.3 versus 20.2) would translate to 900,000 people. The latest estimates from the ACS indicate that 231,840 women diagnosed breast cancer each year.3 For 5-year periods that MIR statistics were accounted for, the difference of MIR translates to over one million. Thus, small differences translate to large impacts when examined for a large population.

A partnership between FQHCs and academic research centers has been a hallmark of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention-funded Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network.33 This partnership has provided the unique opportunity to convene experts from diverse backgrounds (policy, clinical, research, government) in order to develop, implement, and evaluate evidence-based approaches to cancer prevention and control.34–40 The current work demonstrates that academic research could contribute to the evaluation of FQHCs' impact on health disparities. The partnership between FQHCs and academic research centers would be beneficial to improve FQHCs' activities in terms of expanding their services to the area and reducing structural barriers to access to health care. Coming together in this way also may serve to improve methods of data collection.41,42

This work has several limitations and strengths. Ecological studies, while allowing for analyses of cancer incidence and mortality trends in relation to FQHC availability, do not allow to control for individual-level factors, such as obesity, behavioral factors, socioeconomic characteristics, etc., which are necessary for estimating effect modification or controlling confounding.43 Specifically, differential uptake of breast cancer treatment regimens by age and other demographic groups could affect the overall mortality or survival after diagnosis;44 however, we could not take these individual factors into consideration. Although we attempted to adjust for county-level SES indicators, we could not fully account for differences by county. Because the populations that each FQHC serve vary markedly, FQHCs differ in size and the services that they provide. We modeled only existence of FQHCs or mammography services, regardless of characteristics of each FQHC. The size of counties and number of FQHCs in each county vary, but a county with one service site is treated the same as one that has 10 sites in the county, with obvious service dissimilarities. Our research team previously conducted analyses using number of FQHC mammography facilities per 10,000 populations in the county instead of the current approach, with no material differences in the results obtained (counties with a high density of mammography facilities per 10,000 people have lower breast cancer MIR than other counties). In addition, information regarding county-level cancer stage at diagnosis, which is strongly associated with the duration of survival as well as mortality, was unavailable. Therefore, we could not consider the proportion of early-stage breast cancer and its mitigating effects on MIR calculation. Counties with fewer than three incidence cases or deaths due to breast cancer were excluded from the analysis. This may have caused a systematic bias because approximately 85% of excluded counties are rural, while only 49% of included counties are rural. In addition, excluded counties had smaller populations, higher poverty rates, higher proportion of uninsured people, and fewer number of FQHC delivery sites compared with included counties. This systematic bias could mitigate the effect of FQHCs in breast cancer MIR found in our study. In addition, suppressed or missing mortality or incidence rates made it impossible to calculate race-specific MIRs in some counties. This resulted in small sample size and reduced statistical power. We assume that there would be greater and more meaningful differences if MIRs for all counties were included in the analysis. On the other hand, we have demonstrated the feasibility of conducting a large, nationally representative evaluation of breast cancer outcomes.

Despite the FQHCs' efforts aimed at providing quality care to their patients, cancer screening rates at FQHCs are still lower than the national average.45,46 Lack of knowledge about cancer screening, fear of pain or of finding cancer from the screening, lack of physician recommendation, dissatisfaction with patient-provider relationships, poor accessibility, relatively high cost of the test, lack of transportation, and language barriers have been reported as barriers to cancer screening for female patients at community health centers.47,48 Future studies need to address barriers associated with cancer screening in order to facilitate early detection of breast cancer and improve cancer outcomes.

This work represents an interesting research linkage between policy and program evaluation. Many current interventions and approaches in the cancer prevention and control research arena suffer from the lack of ‘hard’ outcome evaluations (such as cancer incidence and mortality). For example, there is a multitude of studies which highlight the benefit of program on intention to receive a mammogram,49–51 but there are many fewer studies that evaluate the program impact on actual receipt of a mammogram.52 Most studies in which receipt of mammography is the outcome rely upon participant self-report, areas where there are mammography registries, or closed electronic medical record systems; none of these are population-based. This current work has the advantage of exploring outcomes with even more “downstream” impact: actual cancer incidence and mortality. While these outcomes have high impact on public health, the type of analysis that we have conducted has a noted weakness of being derived from ecological data. On the other hand, policy makers and legislative bodies are seeking these types of investigations to support meaningful policy changes that have demonstrated impact. We believe that this type of analysis addresses a need for greater emphasis on multi-institutional/multi-discipline driven teams who can use existing data creatively in order to answer important questions regarding the availability of health services on public health outcomes.

Conclusions

FQHCs and the services that they are able to provide may have a direct influence on breast cancer incidence and mortality. This impact appears to be particularly pronounced in urban areas and among whites. These findings have significant public health policy implications by demonstrating the utility of funding for the expansion of services that FQHCs are able to offer as well as potential for growth into areas without FQHC access.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U48/DP001936 and U48/DP005000-01S2 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Prevention Research Centers) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (PIs: Dr. Hébert, Dr. Friedman). Dr. Yip was partially supported by the NCI (R01 CA 124397; PI: S-P Tu). This work also was partially supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention and Control from the Cancer Training Branch of the NCI to Dr. Hébert (K05 CA136975), a Cancer Network Program Center grant from the NCI [(1U54 CA153461-01 Hebert, JR (PI)], and an NCI K01 Career Development Grant to Dr. Tucker-Seeley (1K01CA169041-01).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2015;5–9 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: An independent review. Lancet 2012;380: 1778–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabár L, Vitak B, Chen TH-H, et al. Swedish two-county trial: Impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology 2011;260:658–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paci E. Summary of the evidence of breast cancer service screening outcomes in Europe and first estimate of the benefit and harm balance sheet. J Med Screen 2012;19(Suppl 1):5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RA, Brooks D, Cokkinides V, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2013: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines, current issues in cancer screening, and new guidance on cervical cancer screening and lung cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:88–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine 2009;151:716–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Association of Community Health Centers. A sketch of community health centers: Chart book 2013. Available at: www.nachc.com/client/Chartbook2013.pdf Accessed October22, 2013

- 10.Shin P, Rosenbaum S., Paradise J. Community health centers: The challenge of growing to meet the need for primary care in medically underserved communities. 2012. Available at: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/DHP_Publications/pub_uploads/dhpPublication_3B043800-5056-9D20-3D5DCAA18AC4BD43.pdf Accessed July14, 2014

- 11.Taylor J. The fundamentals of community health centers. 2004. Available at: www.phsi.harvard.edu/quality/clinical_it_safety_net/NHPF_CHC_Fundamentals.pdf Accessed July8, 2014

- 12.Starfield B, Powe NR, Weiner JR, et al. Costs vs quality in different types of primary care settings. JAMA 1994;272:1903–1908 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi L, Stevens GD. The role of community health centers in delivering primary care to the underserved: Experiences of the uninsured and Medicaid insured. J Ambul Care Manage 2007;30:159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meersman SC, Breen N, Pickle LW, Meissner HI, Simon P. Access to mammography screening in a large urban population: A multi-level analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:1469–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson MC, Davis WW, Waldron W, McNeel TS, Pfeiffer R, Breen N. Impact of geography on mammography use in California. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:1339–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celaya M, Berke E, Onega T, et al. Breast cancer stage at diagnosis and geographic access to mammography screening (New Hampshire, 1998–2004). Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez MA, Ward LM, Pérez-Stable EJ. Breast and cervical cancer screening: Impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKinnon JA, Duncan RC, Huang Y, et al. Detecting an association between socioeconomic status and late stage breast cancer using spatial analysis and area-based measures. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:756–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry J, Breen N, Barrett M. Significance of increasing poverty levels for determining late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in 1990 and 2000. J Urban Health 2012;89:614–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadley J, Cunningham P. Availability of safety net providers and access to care of uninsured persons. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1527–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polednak AP. Survival of breast cancer patients in Connecticut in relation to socioeconomic and health care access indicators. J Urban Health 2002;79:211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuhausen K, Grumbach K, Bazemore A, Phillips RL. Integrating community health centers into organized delivery systems can improve access to subspecialty care. Health Aff 2012;31:1708–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gumpertz ML, Pickle LW, Miller BA, Bell BS. Geographic patterns of advanced breast cancer in Los Angeles: Associations with biological and sociodemographic factors (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:325–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarlov E, Zenk SN, Campbell RT, Warnecke RB, Block R. Characteristics of mammography facility locations and stage of breast cancer at diagnosis in Chicago. J Urban Health 2009;86:196–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hébert JR, Daguise VG, Hurley DM, et al. Mapping cancer mortality‐to‐incidence ratios to illustrate racial and sex disparities in a high‐risk population. Cancer 2009;115:2539–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner SE, Hurley DM, Hébert JR, McNamara C, Bayakly AR, Vena JE. Cancer mortality‐to‐incidence ratios in Georgia. Cancer 2012;118:4032–4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams SA, Choi SK, Khang L, et al. Decreased cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios with increased accessibility of federally qualified health centers. J Community Health 2015;40:633–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunkara V, Hébert JR. The colorectal cancer mortality‐to‐incidence ratio as an indicator of global cancer screening and care. Cancer 2015;121:1563–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Cancer Institute. State Cancer Profiles: Dynamic views of cancer statistics for prioritizing caner control efforts in the nation, states, and counties. Available at: http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/index.html Accessed September3, 2013

- 30.Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: A summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:347–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Area Resource File (ARF). 2003. Available at: www.arfsys.com Accessed September1, 2012

- 32.Wang F, McLafferty S, Escamilla V, Luo L. Late-stage breast cancer diagnosis and health care access in Illinois. Prof Geog 2008;60:54–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network. http://cpcrn.org Accessed September8, 2014

- 34.Allen CL, Harris JR, Hannon PA, et al. Opportunities for improving cancer prevention at federally qualified health centers. J Cancer Educ 2014;29:30–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman DA, Whiteside YO, Brandt HM, Young V, Friedman DB, Hebert JR. Assessing readiness for establishing a farmers' market at a community health center. J Community Health 2012;37:80–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman DB, Freedman DA, Choi SK, et al. Provider communication and role modeling related to patients' perceptions and use of a federally qualified health center-based farmers' market. Health Promo Pract 2014;15:288–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman DB, Young VM, Freedman DA, et al. Reducing cancer disparities through innovative partnerships: A collaboration of the South Carolina Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network and Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Cancer Educ 2012;27:59–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCracken JL, Friedman DB, Brandt HM, et al. Findings from the community health intervention program in South Carolina: Implications for reducing cancer-related health disparities. J Cancer Educ 2013;28:412–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freedman DA, Mattison-Faye A, Alia K, Guest MA, Hebert JR. Comparing farmers' market revenue trends before and after the implementation of a monetary incentive for recipients of food assistance. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freedman DA, Choi SK, Hurley T, Anadu E, Hebert JR. A farmers' market at a federally qualified health center improves fruit and vegetable intake among low-income diabetics. Prev Med 2013;56:288–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt HM, Young VM, Campbell DA, Choi SK, Seel JS, Friedman DB. Federally qualified health centers' capacity and readiness for research collaborations: Implications for clinical-academic-community partnerships. Clin Transl Sci 2015. doi: 10.1111/cts.12272 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beeson T, Jester M, Proser M, Shin P. Engaging community health centers (CHCs) in research partnerships: The role of prior research experience on perceived needs and challenges. Clin Transl Sci 2014;7:115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenland S, Morgenstern H. Ecological bias, confounding, and effect modification. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siebel MF, Muss HB. The influence of aging on the early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2005;7:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2013: With special feature on prescription drugs. Hyattsville, MD: 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Health Resources and Service Administration. 2013 health center data. Available at: http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?year=2013 Accessed February5, 2015

- 47.Ogedegbe G, Cassells AN, Robinson CM, et al. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection among low-income minority women in community health centers. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97:162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen JD, Shelton RC, Harden E, Goldman RE. Follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms among low-income ethnically diverse women: Findings from a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutter DR, Steadman L, Quine L. An implementation intentions intervention to increase uptake of mammography. Ann Behav Med 2006;32:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansen LK, Feigl P, Modiano MR, et al. An educational program to increase cervical and breast cancer screening in Hispanic women: A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer Nursing 2005;28:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow‐up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. Cancer 2007;109(S2):359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:1580–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]