Abstract

Objective: Two recent systematic reviews have surveyed the existing evidence for the effectiveness of active videogames in children/adolescents and in elderly people. In the present study, effect sizes were added to these systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were performed.

Materials and Methods: All reviewed studies were considered for inclusion in the meta-analyses, but only studies were included that investigated the effectiveness of active videogames, used an experimental design, and used actual health outcomes as the outcome measures (body mass index for children/adolescents [k=5] and functional balance for the elderly [k=6]).

Results: The average effect of active videogames in children and adolescents was small and nonsignificant: Hedges' g=0.20 (95 percent confidence interval, −0.08 to 0.48). Limited heterogeneity was observed, and no moderator analyses were performed. For the effect of active videogames on functional balance in the elderly, the analyses revealed a medium-sized and significant effect of g=0.68 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.13–1.24). For the elderly studies, substantial heterogeneity was observed. Moderator analyses showed that there were no significant effects of using a no-treatment control group versus an alternative treatment control group or of using games that were especially created for health-promotion purposes versus off-the-shelf games. Also, intervention duration and frequency, sample size, study quality, and dropout did not significantly moderate the effect of active videogames.

Conclusions: The results of these meta-analyses provide preliminary evidence that active videogames can have positive effects on relevant outcome measures in children/adolescents and elderly individuals.

Introduction

Physical activity contributes to a healthy body weight in children and adolescents,1 as well as the quality of life in the general adult population,2 and is a major predictor of physical function in the elderly.3 Promoting physical activity is challenging, however, because behavior is influenced by many factors.4 Interventions have generally had small effects5,6 and have not been able to reverse an alarming increase in obesity rates.7 Undiminished efforts are needed, therefore, to identify new approaches to promoting physical activity.

One example of such a new approach is to incorporate active videogames in interventions. Recently, a new generation of digital gaming systems, which require physical exertion to play the game, has become commercially available. These games are denoted as “active videogames”8 or “exergames”9 (e.g., “Dance Dance Revolution™” [Konami Digital Entertainment, El Segundo, CA] and “Wii Sports Resort™” [Nintendo, Kyoto, Japan]). Several studies have shown that active videogames can have beneficial effects on physical activity and related health outcomes.10–13 On the other hand, several other studies have failed to find significant effects.14,15

So how effective are active videogames? Two recent systematic reviews investigated the effects of active videogames among the young and the old. Both provided a thorough overview of the available research in each domain: One focused on the effects of videogames targeting nutrition behavior and physical activity among children and adolescents (18 years of age and under),16 and the other focused on the effects of active videogames on physical function in the elderly (60 years of age and above).9 In both reviews conclusions regarding effectiveness were based on P values, which is not surprising in light of behavioral science's traditional reliance on P values as the key indicator. Nowadays, however, effect sizes are deemed increasingly important17 because effect sizes, unlike P values, are informative to determine whether an effect is meaningful and substantive.17,18 In this article, we therefore report the effect sizes of the included studies and use meta-analytic procedures to gain a more detailed insight into the meaningfulness and substance of the study results.

At present, several systematic reviews on active videogames have been conducted,9,16,19,20 but only one used meta-analytic procedures.21 That study synthesized the results of 18 studies on the effects of active videogames on acute energy expenditure and concluded that active videogames do indeed facilitate light- to moderate-intensity activities.21 No meta-analysis, however, has assessed whether active videogames can result in increased long-term physical activity, which is more important from a public health perspective than one-time physical exertion.8 Also, no published meta-analysis has focused on direct health outcomes, such as body mass index (BMI).

Although research on active videogames is still in its infancy16 and insights can be expected to evolve quickly, it is important to obtain a quantified estimate of active videogames' effects on health-related outcomes in a “considered synthesis of multiple studies.”22 p.626 In this study, therefore, we added effect sizes to two existing systematic reviews9,16 and performed meta-analyses to provide more fine-tuned insight into the effectiveness of active videogames. The two systematic reviews were chosen because they were published recently and contain all the evidence available to date. Close inspection of three other recent reviews19–21 did not yield additional studies that would have met the inclusion criteria of Lu et al.16 or Larsen et al.9

Materials and Methods

Data sources

Active videogames for children and adolescents. In their systematic review, Lu et al.16 identified studies on the effects of health videogames on childhood obesity-related outcomes. The inclusion criteria were (1) focus on improving or maintaining health, (2) one or more videogames were used as the intervention, (3) use of quantitative outcome measures, (4) target population being the healthcare receiver population (e.g., overweight and healthy children) instead of healthcare providers (e.g., doctors), and (5) original study only. Additionally, included studies must (6) target participants 18 years or younger and (7) include one or more obesity-related health outcome measures such as BMI.

Because of this latter focus on actual biophysical outcomes, the included studies are very much comparable to each other in terms of outcome measures. Indeed, all included studies used BMI as the primary outcome. In terms of intervention approaches and study designs, however, considerable variation was observed, limiting the extent to which the studies are comparable, as the authors noted.16 We therefore added two criteria for inclusion in the present meta-analysis. First, the intervention had to consist of an active videogame in which physical exertion was required for gameplay. This excluded two studies examining the effect of nutrition games and two others that targeted the determinants of physical activity (e.g., knowledge) but did not require physical exertion (see below). Second, we only included studies that compared the effects of the active videogame with an alternative treatment control group or a no-game control group (i.e., using an experimental design). Table 1 shows all studies included in the review of Lu et al.16 and indicates which studies were excluded and why. In total, five studies were included in the present meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Overview of Included and Excluded Studies

| Active videogames focus, study | Included/excluded | Reason for exclusion | Outcome measure used in meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| For children and adolescents (k=14) | |||

| Baranowski et al.48 | Excluded | No physical exertion required to play the game | |

| Bethea et al.10 | Excluded | Observational design | |

| Calcaterra et al.49 | Excluded | Observational design | |

| Christison and Khan50 | Excluded | Observational design | |

| Gao et al.51 | Included | — | BMI |

| Goran and Reynolds52 | Excluded | No physical exertion required to play the game | |

| Maddison et al.11 | Included | — | BMI |

| Madsen et al.15 | Excluded | Observational design | |

| Maloney et al.53 | Included | — | BMI |

| Moore et al.54 | Excluded | Videogame targeted nutrition | |

| Murphy et al.55 | Included | — | BMI |

| Ni Mhurchu et al.56 | Included | — | BMI |

| Chin a Paw et al.57 | Excluded | No control group | |

| Thompson et al.58 | Excluded | Videogame targeted nutrition | |

| For elderly individuals (k=7) | |||

| Anderson-Hanley et al.14 | Excluded | Diverging outcome measure | Muscle strength |

| Franco et al.46 | Included | — | Functional balance |

| Pichierri et al.30 | Included | — | Speed of forward/backward step |

| Pluchino et al.59 | Included | — | Functional balance |

| Rendon et al.12 | Included | — | Functional balance |

| Szturm et al.13 | Included | — | Functional balance |

| Toulotte et al.60 | Included | — | Functional balance |

BMI, body mass index.

Active videogames for elderly individuals

In their systematic review, Larsen et al.9 set out to determine the effects of active videogames on physical outcome measures in elderly individuals. They included research that (1) investigated the effects of active videogames, (2) used randomized controlled trials to compare active videogames with an alternative intervention or no intervention, (3) targeted healthy elderly individuals (>60 years of age) as study participants, and (4) assessed quantitative physical variables, such as aerobic fitness, muscle strength, balance, or body composition, as the outcome measures, using validated assessment tools. It turned out that most studies were performed in the context of functional balance and fall prevention and assessed (aspects of) functional balance as the outcome measure. Therefore, we added the criterion that the studies had to use functional balance, or other strong predictors of falling incidents, such as speed of forward- and backward step,23 as outcome measures. This excluded one study from the analysis that assessed muscle strength (see Table 1).

Study characteristics

All included studies were coded for several intervention characteristics. Intervention duration (in weeks) and frequency (number of sessions per week) were coded from the original publications. Also, it was coded whether the active videogame was especially developed for health-promotion purposes or constituted a commercially available videogame. The latter variable was incorporated because previous research suggests that off-the-shelf (commercial) videogames may be a particular promising tool for health promotion as they tend to be more affordable, accessible, and technologically advanced than videogames developed by researchers for health-promotion purposes.24

With regard to characteristics of the methodology used, sample size was recorded, and it was coded whether the control group received some alternative treatment, such as physical activity knowledge games, or no treatment. Additionally, in the case of the studies of children/adolescents, the methodological quality of the included studies was assessed, using the Cochrane Collaborations risk of bias tool.25,26 This tool assesses risk of bias in seven categories: Sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Risk of bias for each category was determined to be low risk (1 point), unclear risk (0 points), or high risk (−1 point), resulting in a total score for each study between −7 and 7. The first two authors rated the studies independently and then compared their assessments; any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. In the case of the elderly studies, Larsen et al.9 provided an assessment of methodological quality in their systematic review. Therefore, these scores did not have to be obtained anew but could be calculated from their original article by awarding 1 point to a low risk score, 0 points to an unclear risk score, and −1 point to a high risk score. The dropout rate was recorded as an additional indicator of methodological quality.

Effect size measures

For the studies of children/adolescents, BMI scores (including z-scores, percentiles) were chosen as the outcome measure for the meta-analysis as all five included studies assessed BMI as an outcome measure. For the elderly studies, five out of six studies assessed functional balance27 as the primary outcome measure. To ensure optimal comparability between studies, we calculated the effect sizes for functional balance from these five studies to be used in the meta-analysis, thereby ignoring other outcome measures such as self-reported “perceived balance”12,13 and depression.12 When several measures of functional balance were available, for instance, scores on the Unipedal test28 and on the Tinetti test,28 we aimed to aggregate these effect sizes within the same studies as much as possible.29 To this aim, we calculated effect sizes for each measure of functional balance and averaged these to arrive at a total effect size. The remaining study assessed speed of forward and backward step30 as the outcome measure. Because speed of forward and backward step is an important predictor of falling and has been shown to be closely associated with functional balance,23,31 an effect size for this outcome measure was calculated and used in the meta-analysis alongside the five effect sizes for functional balance. As with functional balance, an average effect size was calculated in the case of several different measures of the same construct.

Each study provided a comparison between an active videogame and a control condition. This comparison was summarized using the standardized mean difference as the effect size index. Because Cohen's d, an often-used estimate, is slightly biased toward overestimating the standardized mean difference in small samples, we used Hedges' g, which corrects for sample size and yields an unbiased estimate.32 Conventionally, an effect is considered small when g=0.20 and medium when g=0.50, whereas an effect sizes of g=0.80 is considered large.33 The data were coded such that higher scores indicate lower BMI and better physical function in the intervention condition versus the control condition. Thus, a positive g indicates a positive intervention effect.

Effect sizes were computed from reported means, standard deviations, and n values for the post-test comparisons. If these were not available, means, standard deviations, and n values for the difference scores were used. Otherwise, means, standard deviations, and n values were requested from the authors. If we did not hear from the authors or received incomplete answers, we calculated g from reported test statistics, preferably from analyses without covariates, such that individual difference factors were put back into the error term.34

Data analysis

We synthesized the individual effect sizes using both a fixed-effect model and a random-effects model.32 A fixed-effect model produces a straightforward summary of what was found in our five and six studies, respectively. Fixed-effect models can be used when we want to compute the common effect size for the identified population. However, a disadvantage of fixed-effect models is that the result cannot be generalized to other populations.32 When we do want to generalize to a greater population of studies, random-effects models are generally recommended.32 However, the estimate of between-studies variance that is used in random-effects models lacks precision for meta-analyses using a small number of studies. In other words, when using random-effects models on small datasets, there is a risk that the model is not applied correctly.32 Also, a random-effects model makes the assumption that there is a population of studies and that the k studies included in the meta-analysis are a random selection from this hypothetical population.32,35 Thus, although generalizing the results to a larger number of populations and interventions is very useful, a random-effects model does require making additional assumptions, and these assumptions are essentially not verifiable. Because both approaches have advantages and disadvantages, we chose to report the results of both fixed-effect and random-effects models.

We calculated the within-class goodness-of-fit statistic Q (which is approximately chi-squared distributed, with df=k−1, where k is the number of effect sizes), which tests for homogeneity in the true effect sizes across studies.29,36 A significant Q statistic indicates that moderators can explain the variability in effect sizes across studies. Because the Q statistic has been found to rely greatly on the number of included studies and as a result has limited power in the case of few studies,37 we also calculated the I2 statistic, which can be interpreted as the proportion of total variability explained by heterogeneity.37 In the case of large heterogeneity, we performed moderator analyses with the coded intervention and study characteristics. We tested for categorical moderators with the categorical model test,29 which results in the between-class goodness-of-fit statistic QB, with df=j−1 (where j is the number of categories or groups). A significant between-groups effect indicates that the variance in effect sizes is at least partially explained by the moderator. We tested for continuous moderators using weighted least square regression of the effect sizes onto the continuous moderator.38,39 Significant prediction indicates that the effect sizes vary in a linear manner with the continuous moderator. It should be noted, however, that the statistical power of moderator analyses in meta-analysis is not always high40 and that a large number of studies is generally needed to detect effects.41 Given that research about active videogames is still in its infancy, so that not many published studies exist,9,16 the results of these analyses should be considered with caution. No moderator analyses were performed in case of limited heterogeneity.36 No formal test of publication bias (e.g., examining funnel plots) was performed because these tests are generally not recommended when less than 10 effect sizes are available for analysis.42 Data were analyzed using an Excel™ (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet and with RevMan software.43 The spreadsheet is made available through https://osf.io/rjsg9/

Results

Active videogames for children and adolescents

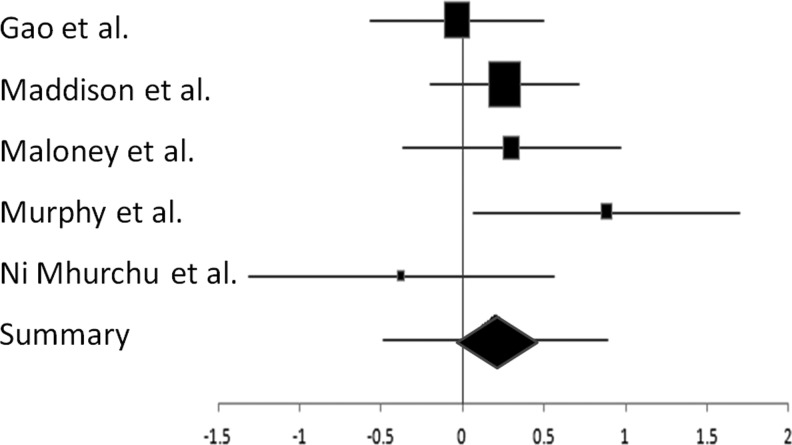

Effect sizes were available for five studies, with a total of 561 participants (Table 2). An analysis using a fixed-effect model revealed a small but significant composite effect size of g=0.20 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.04–0.37). Using a random-effects model to estimate the composite effect size yielded a nonsignificant effect size of g=0.20 (95 percent confidence interval, −0.08 to 0.48). Figure 1 shows a forest plot of the random-effects model. Note that the composite effect size is represented by a diamond, with the width of the diamond indicating the 95 percent confidence interval (i.e., we can be 95 percent certain that our mean effect size falls within this range) and the horizontal line indicating the prediction interval (i.e., we estimate that the true effect in 95 percent of future studies will fall within this range).32 The Q statistic yielded a nonsignificant effect, Q(4)=7.46, P=0.11, indicating limited heterogeneity. Because the Q statistic has been shown to have low power in the case of few studies,37 we also calculated the I2 statistic. This revealed that 46 percent of the variance in effect sizes across studies was attributable to systematic differences between studies, I2=0.46, a proportion that can be classified as low to moderate.37 This result indicates that a larger share of the variance in effect sizes across studies can be attributed to sampling error rather than to moderator variables. We therefore did not perform moderator analyses.

Table 2.

Sample Sizes, Effect Sizes, and Study Characteristics for the Studies of Children and Adolescents

| Intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | n | g | Duration (weeks) | Frequency (session/week) | Game commercially available | Control condition | Study qualitya | Dropout (percent) |

| Gao et al.51 | 126 | −0.04 | 36 | 3 | Yes | No treatment | −5 | 22 |

| Maddison et al.11 | 322 | 0.25 | 24 | NA | Yes | No treatment | 1 | 20 |

| Maloney et al.53 | 58 | 0.30 | 10 | NA | Yes | No treatment | 0 | 10 |

| Murphy et al.55 | 35 | 0.88 | 12 | NA | Yes | No treatment | 0 | 0 |

| Ni Mhurchu et al.56 | 20 | −0.38 | 12 | NA | Yes | No treatment | 2 | 0 |

Range, −7 to 7.

NA, not available.

FIG. 1.

Forest plot for the studies in children/adolescents.11,51,53,55,56

Active videogames for elderly individuals

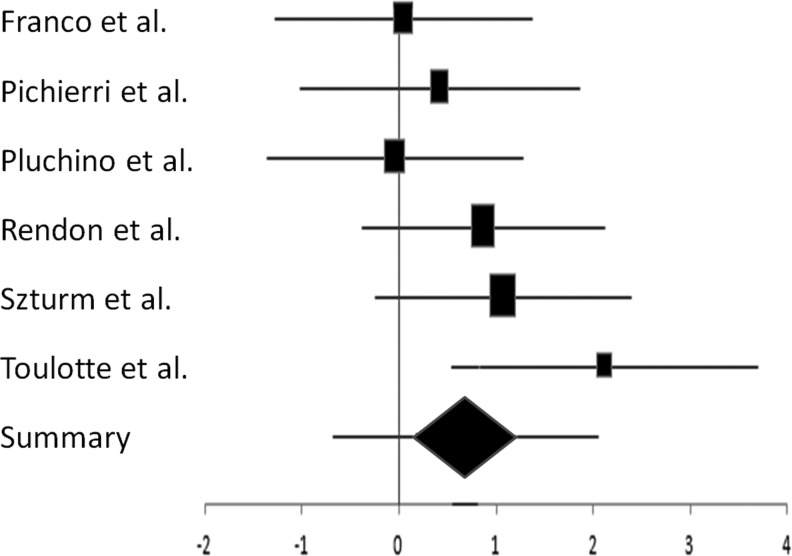

Effect sizes were available for six studies, with a total of 142 participants (Table 3). Using a fixed-effect model, the meta-analysis revealed a medium to large and significant composite effect size of g=0.64 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.29–0.99). A random-effects model showed a medium to large and significant effect size of g=0.68 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.13–1.24). Figure 2 shows a forest plot of the random-effects model. The Q statistic yielded a significant effect, Q(5)=12.37, P=0.03, indicating heterogeneity. Calculation of the I2 statistic revealed that 68 percent of the variance in effect sizes across studies was attributable to systematic differences between studies, a proportion that can be classified as moderate to high.37 This result indicates that a larger share of the variance in effect sizes across studies can be attributed to moderator variables than to sampling error, which calls for an investigation of potential moderators.

Table 3.

Sample Sizes, Effect Sizes, and Study Characteristics for Studies of the Elderly

| Intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | n | g | Duration (weeks) | Frequency (sessions/week) | Game commercially available | Control condition | Study qualitya | Dropout (percent) |

| Franco et al.46 | 21 | 0.04 | 3 | 2 | Yes | No treatment | −1 | 16 |

| Pichierri et al.30 | 15 | 0.42 | 12 | 2 | No | Usual care | −3 | 40 |

| Pluchino et al.59 | 27 | −0.05 | 8 | 2 | Yes | Alternative training program | −1 | 33 |

| Rendon et al.12 | 34 | 0.86 | 6 | 3 | Yes | No treatment | 4 | 15 |

| Szturm et al.13 | 27 | 1.07 | 8 | 2 | No | Usual care | 3 | 10 |

| Toulotte et al.60 | 18 | 2.11 | 20 | 1 | Yes | No treatment | 1 | 0 |

Range, −7 to 7.

FIG. 2.

Forest plot for the studies in the elderly.12,13,30,46,59,60

Moderator analyses revealed that active videogames that were especially developed for health-promotion purposes did not result in significantly different intervention effects than commercially available videogames: QB(1)=0.03, P=0.87. Also, studies in which the control group received some alternative treatment, such as physical activity knowledge games, did not result in significantly different intervention effects than studies in which the control group received no treatment: QB(1)=0.20, P=0.65. Nonsignificant effects were also found for sample size [β=−0.12, t(5)=−0.22, P=0.84], intervention frequency (number of sessions per week) [β=−0.49, t(5)=−0.88, P=0.42], intervention duration (in weeks) [β=0.77, t(5)=1.38, P=0.23], study quality as assessed by Larsen et al.9 [β=0.50, t(5)=0.88, P=0.42], and dropout [β=−0.76, t(3)=−1.33, P=0.24].

Discussion

The present research aimed to add to two recent systematic reviews9,16 by calculating effect sizes for the reviewed studies and synthesizing those using meta-analytic procedures. The results showed a small positive effect of active videogames on children's BMI (g=0.20) and a medium to large positive effect on functional balance in the elderly (g=0.68). This synthesis suggests that active videogames can be helpful in improving BMI among children and functional balance among the elderly.

As active videogames research is still in its infancy, only a limited number of studies could be included in the meta-analyses (k for children/adolescents=5; k for elderly=6). As such, the present research offers a first, preliminary, estimate of active videogames' effects. When more effectiveness studies become available, this estimate will likely be revised. As a first estimate of the effects of active videogames, however, we argue that the present meta-analyses are both necessary and informative.

Meta-analyses are necessary to obtain a meaningful estimate of the substance of active videogame effects. Previous empirical studies and systematic reviews have primarily relied on P values.8,9,16 Effect sizes, however, are more appropriate for intervention evaluation.17,18 Although the flaws of null-hypothesis significance testing have been discussed for some time,44 this discussion has recently increased in intensity. Some authors go so far as to proposing wholly abolishing null-hypothesis significance testing in favor of “the new statistics,” which rely on effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analyses.45 In keeping with this trend, this article obtained effect sizes for relevant studies to obtain an estimate of the substance of active videogame effects.

The present meta-analyses are informative in that they are generally supportive of claims that active videogames can be effective health-promoting interventions. Previous systematic reviews have provided comprehensive overviews of published empirical studies, but because these have shown mixed results, they have been unable to draw firm conclusions about active videogames' effects. Lu et al.,16 for instance, do not comment specifically on the overall effectiveness of active videogames. The conclusion of Larsen et al.9 is that more research is necessary to study the effects of active videogames for the elderly. Another recent systematic review8 concluded that active videogames result in acute energy expenditure, but that it is not clear if active videogames result in longer-term health benefits. The preliminary estimates provided by the present meta-analytic procedures suggest that active videogames do indeed lead to improvements in children's BMI and in functional balance in the elderly.

It should be noted that the two sets of studies were vastly different in terms of populations and outcome measures. Thus, we can observe that the composite effect for the studies in the elderly was larger than the composite effect for the studies in children, but such a comparison would hardly be meaningful considering the vast differences between the studies. At the same time, active videogames can be used for many other populations and in many other contexts, limiting the extent to which the present findings can be generalized to a “general” effectiveness of active videogames. As such, the present meta-analyses offer preliminary estimations of the effects of active videogames, but only in these two specific health domains.

It should also be noted that the relatively small number of included studies in both meta-analyses induced severe limits on the conclusions that we can derive. For one, when the number of included studies is small, the estimate of the between-studies variance is imprecise, therefore compromising the precision of random-effects models.32 In addition, moderator analyses have only limited power with a small set of studies.40,41 This latter limitation is particularly noteworthy given the substantial heterogeneity that was found in the elderly studies. Our results revealed that 68 percent of the variance in effect sizes across the elderly studies was attributable to systematic differences. Thus, despite the fact that inclusion criteria resulted in similar populations across studies (healthy over-60 year olds) and similar interventions (active videogames), the estimate of heterogeneity suggested that the extent to which studies could be compared was limited. Perhaps this was due to the use of different assessment procedures for functional balance, for instance, the Berg Balance Scale,13 the Tinetti test,46 and the speed of backward and forward step.30 When selecting studies for a meta-analysis, identical assessment procedures are preferable. However, there is often no general consensus on what is the best way to assess important constructs, and studies tend to differ in the procedures that they use. As a result, it is quite common in meta-analyses to include different assessment procedures (e.g., Conn et al.47). In our case, we argue that it is justified to include studies with different assessment procedures for functional balance. However, it should be noted that the heterogeneity that may have resulted from this limits the extent to which studies could be compared.

In sum, the present results should be seen in light of the limited number of studies in both meta-analyses and the resultant limited possibilities to investigate the encountered heterogeneity. Caution is therefore warranted when interpreting the present results. Nevertheless, we argue that the composite effect sizes found in the present meta-analyses allow for some cautious optimism concerning the potential effects of active videogames for obesity prevention in the young and improvement of functional balance in the old. In future, meta-analytic procedures remain necessary to obtain valid estimates of active videogame effects. With additional empirical studies coming forth, effect size estimates are likely to become more reliable, moderator analyses will have increased power,40,41 and it will be possible to test for publication bias.42

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Must A, Tybor DJ. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: A review of longitudinal studies of weight and adiposity in youth. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29(Suppl 2):S84–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: A systematic review. Prev Med 2007; 45:401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldspink DF. Ageing and activity: Their effects on the functional reserve capacities of the heart and vascular smooth and skeletal muscles. Ergonomics 2005; 48:1334–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Dzewaltowski DA, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity—the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med 2002; 23:5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (12):CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, King AC. Promoting physical activity for older adults—The challenges for changing behavior. Am J Prev Med 2003; 25:172–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008; 299:2401–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc AG, Chaput JP, McFarlane A, et al. Active video games and health indicators in children and youth: A systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8:e65351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen LH, Schou L, Lund HH, Langberg H. The physical effect of exergames in healthy elderly: A systematic review. Games Health J 2013; 2:205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bethea TC, Berry D, Maloney AE, Sikich L. Pilot study of an active screen time game correlates with improved physical fitness in minority elementary school youth. Games Health J 2012; 1:29–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maddison R, Foley L, Ni Mhurchu C, et al. Effects of active video games on body composition: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94:156–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rendon AA, Lohman EB, Thorpe D, et al. The effect of virtual reality gaming on dynamic balance in older adults. Age Ageing 2012; 41:549–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szturm T, Betker AL, Moussavi Z, et al. Effects of an interactive computer game exercise regimen on balance impairment in frail community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2011; 91:1449–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, Brickman AM, et al. Exergaming and older adult cognition: A cluster randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen KA, Yen S, Wlasiuk L, et al. Feasibility of a dance videogame to promote weight loss among overweight children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161:105–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu AS, Kharrazi H, Gharghabi F, Thompson D. A systematic review of health videogames on childhood obesity prevention and intervention. Games Health J 2013; 2:131–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kline RB. Beyond Significance Testing: Reforming Data Analysis Methods in Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volker MA. Reporting effect size estimates in school psychology research. Psychol Schools 2006; 43:653–672 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biddiss E, Irwin J. Active video games to promote physical activity in children and youth: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010; 164:664–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng W, Crouse JC, Lin J-H. Using active video games for physical activity promotion: A systematic review of the current state of research. Health Educ Behav 2013; 40:171–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng W, Lin JH, Crouse J. Is playing exergames really exercising? A meta-analysis of energy expenditure in active video games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011; 14:681–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutton AJ, Higgins JPI. Recent developments in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2008; 27:625–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki BE, McIlroy WE. Control of rapid limb movements for balance recovery: Age-related changes and implications for fall prevention. Age Ageing 2006; 35(Suppl 2):ii12–ii18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange B, Flynn S, Rizzo A. Initial usability assessment of off-the-shelf video game consoles for clinical game-based motor rehabilitation. Phys Ther Rev 2009; 14:355–363 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:264–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabari JS. Optimizing motor skill using task-related training. In: Radomski MV, Trombly-Lathan CA, eds. Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunction, 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008: 618–641 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pichierri G, Coppe A, Lorenzetti S, et al. The effect of a cognitive-motor intervention on voluntary step execution under single and dual task conditions in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Interv Aging 2012; 7:175–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bijlsma AY, Pasma JH, Lambers D, et al. Muscle strength rather than muscle mass is associated with standing balance in elderly outpatients. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14:493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson BT. DSTAT: Software for the meta-analytic review of research literatures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laird NM, Mosteller F. Some statistical methods for combining experimental results. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1990; 6:5–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 1998; 3:486–504 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327:557–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Card NA. Applied Meta-analysis for Social Science Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedges LV, Pigott TD. The power of statistical tests for moderators in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 2004; 9:426–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hempel S, Miles JNV, Booth MJ, et al. Risk of bias: A simulation study of power to detect study-level moderator effects in meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2013; 2:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot assymetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program], version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J. The earth is round (p-less-than .05). Am Psychol 1994; 49:997–1003 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cumming G. The new statistics: A how-to guide. Aust Psychol 2013; 48:161–170 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franco JR, Jacobs K, Inzerillo C, Kluzik J. The effect of the Nintendo Wii Fit and exercise in improving balance and quality of life in community dwelling elders. Technol Health Care 2012; 20:95–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Cooper PS, et al. Meta-analysis of workplace physical activity interventions. Am J Prev Med 2009; 37:330–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Thompson D, et al. Video game play, child diet, and physical activity behavior change: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 2011; 40:33–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calcaterra V, Larizza D, Codrons E, et al. Improved metabolic and cardiorespiratory fitness during a recreational training program in obese children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2013; 26:271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christison A, Khan HA. Exergaming for health: A community-based pediatric weight management program using active video gaming. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012; 51:382–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao Z, Hannan P, Xiang P, et al. Video game-based exercise, Latino children's physical health, and academic achievement. Am J Prev Med 2013; 44(Suppl 3):S240–S246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goran MI, Reynolds K. Interactive multimedia for promoting physical activity (IMPACT) in children. Obes Res 2005; 13:762–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maloney AE, Bethea TC, Kelsey KS, et al. A pilot of a video game (DDR) to promote physical activity and decrease sedentary screen time. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16:2074–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore JB, Pawloski LR, Goldberg P, et al. Childhood obesity study: A pilot study of the effect of the nutrition education program Color My Pyramid. J Sch Nurs 2009; 25:230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy ECS, Carson L, Neal W, et al. Effects of an exercise intervention using Dance Dance Revolution on endothelial function and other risk factors in overweight children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009; 4:205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ni Mhurchu C, Maddison R, Jiang Y, et al. Couch potatoes to jumping beans: A pilot study of the effect of active video games on physical activity in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008; 5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chin a Paw M, Jacobs WM, Vaessen EPG, et al. The motivation of children to play an active video game. J Sci Med Sport 2008; 11:163–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson D, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, et al. Boy Scout 5-a-Day Badge: Outcome results of a troop and Internet intervention. Prev Med 2009; 49:518–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pluchino A, Lee SY, Asfour S, et al. Pilot study comparing changes in postural control after training using a video game balance board program and 2 standard activity-based balance intervention programs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93:1138–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toulotte C, Toursel C, Olivier N. Wii Fit® training vs. adapted physical activities: Which one is the most appropriate to improve the balance of independent senior subjects? A randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil 2012; 26:827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]