Abstract

Background: Pregnant women are at increased risk for complications associated with influenza. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy helps protect both pregnant women and infants less than 6 months of age from contracting the flu. This study investigated influenza prevention and treatment practices of obstetrician-gynecologists (ob-gyns) during the influenza season immediately following the 2009–2010 H1N1 season.

Methods: In 2011, surveys were sent to two groups of Fellows of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Group 1 was 907 ob-gyns who responded to our previous survey on practice and knowledge of influenza vaccination, diagnosis, and treatment during the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Group 2 was 2,293 new recipients randomly selected from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists database. Data were analyzed in 2013.

Results: A high proportion of pregnant patients were reported to be vaccinated against influenza (71.7%); however, the data suggest that in general preventative practices decreased between the 2009–2010 H1N1 season and 2010–2011 season. A higher proportion of women eligible for Medicaid in a practice was associated with a lower estimate of vaccination rate. Ob-gyns with more than 20 years of practice were more likely to be concerned about the risks of antivirals and less likely to routinely prescribe them.

Conclusions: Ob-gyns may be overestimating the proportion of pregnant women being vaccinated. The gains in vaccination and influenza prevention practices from the H1N1 pandemic have not been completely retained. Discrepancies in the use of anti-virals to treat suspected or confirmed influenza in pregnant patients exist and need to be addressed.

Introduction

Pregnant women are at increased risk for complications associated with influenza.1 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend that pregnant women receive inactivated influenza vaccine regardless of pregnancy trimester.2,3 Antenatal influenza immunization also protects infants of less than 6 months of age who would otherwise be at increased risk for influenza-associated complications.4

Prevention is best; however, treatment for pregnant women with confirmed or suspected influenza typically is successful when antivirals are used within the first 2 days of symptom onset. Data from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed that pregnant women who received treatment in the first 2 days after onset of influenza symptoms were significantly less likely to require admission to the intensive care unit or to die than women treated more than 2 days after symptom onset.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends early empiric treatment with influenza antiviral medication.6,7

Health care providers play a crucial role in determining whether pregnant women receive early treatment with antiviral medications and whether they receive influenza vaccination. In a recent survey, pregnant women whose health care providers recommended and offered influenza vaccination were more likely to receive the influenza vaccine (73.6%) compared with pregnant women who received a recommendation but no offer (47.9%) and women who received neither a recommendation nor an offer (11.1%).8 Thus, it is important to understand the knowledge, attitudes and practices of obstetrician-gynecologists (ob-gyns) related to influenza prevention and treatment during pregnancy. Previous studies of ob-gyns have assessed ob-gyns' attitudes and identified factors associated with ob-gyns being more likely to recommend vaccination and early treatment; however, these studies were conducted before9,10 or during11,12 the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Here we conducted a study of ob-gyns regarding knowledge, attitudes and practices related to influenza prevention and treatment during the 2010–2011 influenza season, the first season following the 2009 HN1 pandemic, as a follow-up to our study conducted during the H1N1 pandemic.11

Materials and Methods

A self-administered survey was mailed to a total sample of 3,200 ob-gyns. Eligible responders were defined as ob-gyns who were currently involved in treating pregnant patients. Those who were not eligible were instructed to check the appropriate box and return the uncompleted survey. These 3,200 ob-gyns represented two sample groups: Group 1 (n=907) and Group 2 (n=2293). Group 1 was comprised of the 907 out of 1,310 ob-gyns that had responded to our 2009 H1N1 flu season survey11 (conducted in the first half of 2010) who treated pregnant patients, and were thus, in theory, 100% eligible. Group 1 was representative of ACOG in age, sex, and geographic location.11 We anticipated a response rate of 50%–55% for Group 1, since these ob-gyns were more likely to respond to a second survey given their previous history of survey responses regarding this topic. Thus, we expected 450–500 eligible responders from Group 1.

Group 2 ob-gyns were chosen via a random sampling of ACOG Fellows or Junior Fellows excluding the 3,116 that had been selected for the previous survey (n=30,569). Group 2 ob-gyns were also representative of ACOG in age, sex, and geographic location. We predicted an effective response rate of 20%–25% for eligible members of Group 2 due to this group being comprised of ob-gyns with no previous history of survey responses and because historically about 20% of our Fellows do not treat pregnant patients. Our sample size for Group 2 was chosen to produce an approximately equal number of eligible responders as from Group 1. The expected sample size of at least 450 from each group results in a 95% confidence interval for frequency data within each group, which enables a 10% difference between groups to be distinguished with an α of 0.05 and power of 80%.

The survey was accompanied by a cover letter and prepaid return envelope; no incentives were offered to the participants. Initial mailing was conducted in June, 2011. The second, third, and fourth mailings were conducted to all nonrespondents 4–5 weeks after the first, second, and third mailings, respectively. Data collection ended Dec 31, 2011. The project was reviewed for human subject concerns by the CDC and ACOG and was determined to be public health practice, not research; therefore, review by an institutional review board was not needed.

The survey consisted of 33 questions regarding prevention and treatment of influenza in pregnant women. It included questions on basic demographics of respondents (age, sex, years in practice, type of practice), their patient population (Medicaid eligibility, race/ethnicity), and their attitudes and practices regarding influenza vaccination of pregnant women. Several questions asked the ob-gyns to answer for both the current influenza season (2010–2011) and for the past H1N1 pandemic season (2009–2010).

A measure of effort toward preventing and treating influenza (Practice Effort) was constructed from six basic clinical practices, with each practice scored on a scale from always (4 points) to never (0 points). This measure was used in multivariate analyses of covariance regarding the proportion of pregnant patients that were vaccinated against influenza and other outcomes, and to compare changes in practice between the two seasons by members of Group 1.

Analyses were performed in 2013 using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp.). We calculated distribution of frequencies for each question in the survey, excluding respondents from a question denominator who did not provide an answer to that question. Continuous variables were examined using correlation, analysis of variance, and analysis of covariance. Categorical variables were examined using chi-square. A comparison of the practice effort score between the previous survey and this survey by responders from Group 1was assessed using a paired-sample t-test. The differences in individual practices within the practice effort score were tested using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. We used two-sided statistical inferences and a significance level of a p-value of 0.05 or less.

Results

Of the 3,200 surveys that were mailed to both Group 1 and Group 2 ob-gyns, 11 were returned as undeliverable. Among the ob-gyns who received the survey, 1,196 returned the survey for a total response rate of 37.5% (1196/3189). Of those who returned the survey, 240 (20.1%) opted out of the study as it was not relevant to their practice structure. The data analyses reflect the responses of 956 total Group 1 and Group 2 eligible participants. The response rate calculations are further broken down as follows: of the 907 Group 1 ob-gyns, 3 ob-gyns were unreachable and 473 returned the survey for a total Group 1 response rate of 52.3% (473/904). Of those who returned the survey, 19 (4.0%) opted out of the study as they no longer treated pregnant patients. Thus, total eligible Group 1 responders is 454 (50.1%). Of the 2293 Group 2 ob-gyns, 8 ob-gyns were unreachable and 723 returned the survey for a total Group 2 response rate of 31.6% (723/2285). Of those who returned the survey, 221 (30.6%) opted out of the study as it was not relevant to their practice structure. Thus, total eligible Group 2 responders is 502 (21.9%).

The resulting response rates matched our predicted response rates for each group respectively and yielded an almost equal set of ob-gyn eligible respondents in each group. There was no difference between responders and nonresponders for either Group 1 or Group 2 in the proportion of men versus women who responded or in mean age (p>0.1 in all cases). There were no differences in demographics between the new recipients of the survey (Group 2) and the responders from the previous study (Group 1) (Table 1), and few significant differences in responses between the groups. Accordingly, the results were pooled for most analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic Comparisons Between Group 1 and Group 2 Ob-Gyns

| Demographics | Group 1 | Group 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 454 | 502 | |

| Male (%) | 47.8% | 52.9% | NS |

| Female (%) | 52.2% | 47.1% | NS |

| Solo practice (%) | 5.0% | 15.6 | NS |

| Ob-gyn specialty partnership (%) | 49.1% | 49.0% | NS |

| Multispecialty group (%) | 12.1% | 13.0% | NS |

| University (%) | 12.1% | 11.6% | NS |

| Mean years in practice | 18.8±0.5 | 19.2±0.4 | NS |

| Primary care very importanta (%) | 45.4% | 43.2% | NS |

Percentage of respondents who answered “very important” to the question, “Do you consider primary care/preventive medicine an important part of your clinical practice?”

NS, not significant.

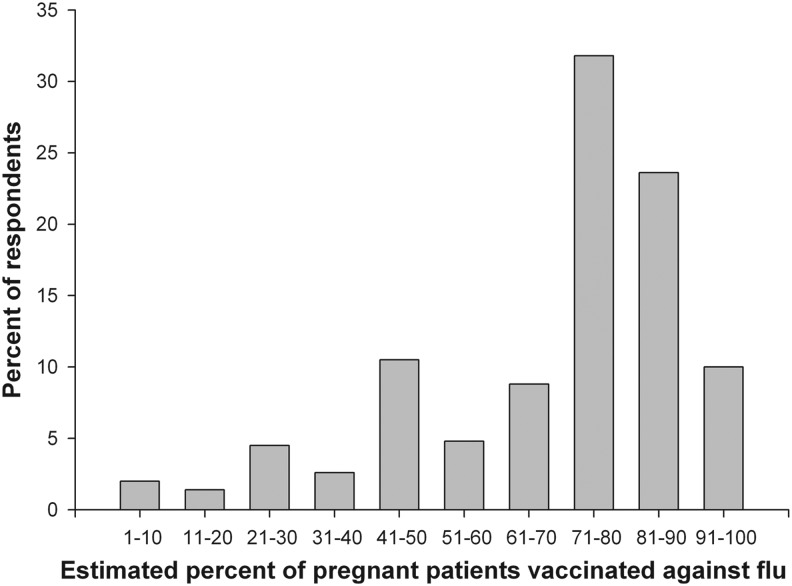

Almost all (93.7%) ob-gyns reported they were vaccinated against influenza during the 2010–2011 season. Less than half (45.8%) reported that their staff were required to be vaccinated, but almost all of the rest reported that the flu vaccine was strongly recommended to their staff. Most respondents (79.6%) indicated that they routinely administered influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients, and most ob-gyns would recommend influenza vaccination to their pregnant patients during any trimester (84.2%), with 15.4% recommending it for only trimesters 2 and 3. On average the ob-gyns estimated that about 7 of every 10 (71.7%; Fig. 1) of their pregnant patients were vaccinated against influenza during the 2010–2011 season.

FIG. 1.

Estimated proportions of pregnant patients vaccinated during the 2010–2011 season as reported by the study respondents. Ob-gyns were asked to report a number between 0% and 100% as their best estimate for the percent of their pregnant patient population that had been vaccinated against influenza during the 2010–2011 season. Responses were grouped in 10% intervals in this histogram.

Virtually all of the responding ob-gyns (>97%) that offered influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients during the 2010–2011 post-H1N1 influenza season reported they offered both regular and H1N1 influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients during the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza season. However, 17.8 % and 34.6% of ob-gyns who offered regular and H1N1 influenza vaccine respectively during the H1N1 season reported they did not offer influenza vaccine during the 2010–2011 season. Several other preventive measures were less commonly reported for the 2010–2011 season as well. For example, 58.6% of ob-gyns reported questioning arriving patients about influenza-like symptoms and separating those patients with symptoms from nonsymptomatic patients in 2009–2010, but that value dropped to 44.5% in 2010–2011.

The practice effort score had a skewed normal distribution with two peaks, the first being ob-gyn respondents that scored 18 (11.4% of respondents), and the second being those that received the highest possible score (16% of respondents) (Fig. 2). A direct comparison of practice effort score among respondents from Group 1 between the previous survey and this survey demonstrated a significant decline in Practice Effort (mean previous survey=19.3±0.2; mean current survey=18.7±0.2; p<0.001). Examining the individual aspects of the practice effort score among Group 1 showed that many practices were more common during the H1N1 pandemic (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of the practice effort score based on the six influenza prevention practices listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Group 1 U.S. Ob-Gyns Who Answered “Always” or “Frequently” to the Six Basic Clinical Practices for 2009–2010 H1N1 Influenza Season and 2010–2011 Influenza Season Surveys

| Practicesa | 2009–2010 H1N1 season | 2010–2011 season | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encourage vaccination against seasonal influenza | 97.0% | 96.5% | 0.221 |

| Discuss social distancing (e.g., minimizing contact with sick individuals, avoiding crowded public gatherings) | 78.4% | 73.6% | 0.002 |

| Promote frequent hand washing | 87.0% | 81.7% | 0.036 |

| Discuss cough etiquette | 61.7% | 60.4% | 0.117 |

| Discuss early symptom recognition | 77.1% | 64.6% | 0.001 |

| Discuss prompt treatment of fever with fever-reducing medicines | 74.4% | 67.1% | 0.001 |

Six basic clinical practices that make up the practice effort score.

Boldface p-Values indicate significance at the p<0.05 level.

A general linear model examining the estimated proportion of vaccinated pregnant patients in the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza season and the 2010–2011 post-H1N1 influenza season found ob-gyn sex, importance of primary care, years of practice, proportion of patients eligible for Medicaid, and the practice effort score all significant factors for 2010–2011 influenza season, but only importance of primary care, proportion of patients eligible for Medicaid, and the practice effort score were significant for the H1N1 flu season. The proportion of patients eligible for Medicaid is negatively associated with the proportion of pregnant patients vaccinated against influenza in both seasons; the importance of primary care and practice effort were positively associated for both seasons. There was a significant interaction between ob-gyn sex and the importance of primary care for the 2010–2011 influenza season only, with men displaying a larger effect than women (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated Marginal Means of Pregnant Patients Vaccinated Against Influenza, by Gender and Importance of Primary Care

| Proportion of pregnant patients vaccinated | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| 2009–2010 H1N1 season | ||

| Men | ||

| Primary care very important | 74.4% (162) | 71.3–77.5% |

| Primary care important | 72.4% (171) | 69.4–75.4% |

| Primary care not important | 65.7% (24) | 58.0–73.5% |

| Women | ||

| Primary care very important | 75.6% (180) | 72.7–78.4% |

| Primary care important | 75.6% (194) | 72.8–78.4% |

| Primary care not important | 69.3% (22) | 61.2–77.3% |

| 2010–2011 season | ||

| Men | ||

| Primary care very important | 73.9% (162) | 70.6–77.2% |

| Primary care important | 67.9% (171) | 64.7–71.1% |

| Primary care not important | 59.1% (24) | 50.8–67.3% |

| Women | ||

| Primary care very important | 73.5% (180) | 70.5–76.6% |

| Primary care important | 74.2% (194) | 71.2–77.2% |

| Primary care not important | 70.4% (22) | 61.8–79.0% |

Number of respondents in each category is shown in parentheses. Other parameters fixed at: years in practice=18; percentage of patients eligible for Medicaid=32.2%; and practice effort score=18.6.

Concern regarding the safety of antivirals had an effect on prescribing practice, with a greater proportion of ob-gyns who were concerned or very concerned regarding safety, responding that they do not routinely prescribe antivirals (31.7% versus 16.3% and 13.5% who were slightly or not concerned, respectively; p<0.001), and a higher proportion who were concerned or very concerned responding that gestational age affected their decision to prescribe (11.8% versus 8.1% and 3.4% who were slightly or not concerned, respectively; p=0.001). Ob-gyns with more than 20 years of practice were more likely to be concerned about the risks of antivirals for healthy pregnant women (50.9% versus 39.7%; p=0.038).

The capability to perform rapid antigen testing was more common among ob-gyns with fewer years of practice (p=0.009). However, a direct comparison of this capability among Group 1 respondents indicated that this capability is increasing (26.2% in survey 1 versus 32.2% in survey 2; p<0.001).

Discussion

Pregnant patients are more likely to receive the influenza vaccine if their doctor recommends it and offers vaccination on-site.13,14 For those ob-gyns who did not offer influenza vaccines during the 2010–2011 post-H1N1 influenza season, an opportunity may have been missed to ensure that their pregnant patient population was protected against influenza infection. Additionally, when comparing the results of respondents that participated in both the previous and current study, respondents were less likely to counsel their pregnant patients on ways to avoid contracting influenza during the 2010–2011 season than they were during the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza season (Table 2). Thus, it can be argued that influenza vaccination and patient education compliance post-the H1N1 influenza season decreased.

Previous studies found ob-gyns were offering their pregnant patient population both the seasonal and H1N1 influenza vaccines during the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza season at a higher rate than what was observed during prior influenza seasons. This increased rate was attributed to several potential factors, many of which were directly associated with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the amount of coverage it received both in mainstream media and professional publications.11,13 Another factor reported to have influenced the higher rate of influenza vaccination during the 2009–2010 H1N1 season, was the distribution of H1N1 vaccines at no cost to providers.11 The high cost of ordering and storing vaccines is an issue that has been cited as a barrier to influenza vaccination in the past, and it is likely to be a similar barrier in the future when complimentary influenza vaccines are not provided.9 The negative association observed in this study between the proportion of Medicaid patients and the proportion of pregnant patients vaccinated against influenza agrees with similar studies that have found influenza vaccination disparities when comparing rates of vaccination between Medicaid-eligible populations and non-Medicaid-eligible populations. Such studies have suggested several factors that may contribute to this observed disparity including financial risks for providers if the actual provider cost of administering the vaccine is greater than the Medicaid reimbursement rate, lack of patient awareness about the importance of receiving the influenza vaccination, and unstable vaccine supplies that reduce the availability of vaccines to underserved populations.15,16,17 Our study data indicate that the aforementioned positive changes observed to affect influenza prevention and treatment during a pandemic season do not completely carry over to nonpandemic seasons, and perhaps even less so for Medicaid-eligible patients.

Additionally, our study data indicate that ob-gyns who were concerned or very concerned about the safety of antiviral drugs for pregnant women were less likely to prescribe antivirals for treatment of flu-like symptoms in their pregnant patient population. Ob-gyns with greater than 20 years of practice were more concerned about prescribing antivirals to healthy pregnant women, than their colleagues who had been in practice for fewer years. Data from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic show that pregnant women who receive antiviral treatment in the first 2 days after onset of influenza symptoms are significantly less likely to require intensive care unit admission or to die than women treated more than 2 days after symptom onset.5 Consequently, the differences in antiviral use perceptions between ob-gyns with more years in practice and those with less is an area in which a knowledge deficit exists which may increase the probability pregnant women will suffer significant morbidity from an influenza infection.

A strength of the study is the ability to directly compare responses to identical questions from the 2010 and 2011 surveys among Group 1 participants. The main weaknesses are those that exist in survey-based studies. Both the 2010 and 2011 surveys relied on ob-gyn recall and the data were self-reported. It is also possible that ob-gyns with more concern about and/or more compliant with influenza vaccination recommendations may have been more likely to respond. The lack of demographic differences between responders and nonresponders argues against nonresponse bias, but it cannot be excluded.

The recommendations made by ob-gyns and the services they offer their patients are integral to increasing the likelihood a pregnant patient will be vaccinated against influenza infection. To ensure pregnant patients are being provided with the best care possible, it is important that the knowledge, practices, and attitudes of ob-gyns are frequently assessed to determine where potential problems may exist. Despite ACIP and ACOG recommendations, influenza vaccine coverage rates among pregnant women remain relatively low. Significant improvements in coverage rates have been observed in recent years—up from 11% during the 2001–2002 influenza season to 50.5% during the 2012–2013 influenza season.14,18 Our data suggest an even higher coverage rate (71.7%); however, data reported by the ob-gyn respondents could not be checked through chart review, and it is possible that the ob-gyns are overestimating the proportion of pregnant patients that are being vaccinated or that the ob-gyns that responded to our surveys were those who were more likely to routinely administer the influenza vaccine or encourage their patients to receive it. This could potentially explain the high vaccination rate reported by ob-gyns in both this and the previous study11 as compared with the national average. Nevertheless, the possibly exaggerated vaccination rate (71.7%) is still below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% seasonal influenza vaccine coverage for pregnant women.19

Conclusions

Reported influenza vaccination rates for the 2010–2011 post-H1N1 influenza season were higher than the national average,18 but still below the Healthy People 2020 goal. The proportion of ob-gyns offering flu vaccination to their pregnant patients declined from the H1N1 pandemic season. Preventative measures also decreased between the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza season and 2010–2011 influenza season. Thus, the great strides in influenza prevention made during the 2009–2010 H1N1 season do not appear to be sustained during non-pandemic years.

The recommendations made by ob-gyns and the services they offer their patients are integral to increasing the likelihood a pregnant patient will be vaccinated against influenza infection and in sustaining advances made in pandemic years through non-pandemic years. Ob-gyns have the ability to directly affect the rate at which their pregnant patient population is vaccinated for influenza. Encouraging their patients to receive the vaccination, offering it on-site, and utilizing patient reminder systems have been shown to improve vaccination rates.11,13,14 Additionally, improvements in health policy to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates, stabilize vaccine supplies, and fund mass media vaccination campaigns could greatly serve to increase coverage especially in underserved populations.17

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the cooperative agreement U65PS000813-03 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services, and by the cooperative agreement UA6MC19010 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The authors thank all the obstetrician-gynecologists who participated in the survey for their time, and also Sonja Rasmussen, MD, MS, and William Callaghan, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their advice and assistance in matters concerning this study. It should be noted that the findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and may not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:S3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62:1–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 608: Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:648–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinhoff MC, Omer SB. A review of fetal and infant protection associated with antenatal influenza immunization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:S21–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. . Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA 2010;303:1517–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, et al. . Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2011;60:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen SA, Kissin DM, Yeung LF, et al. . Preparing for influenza after 2009 H1N1: special considerations for pregnant women and newborns. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204 6 Suppl 1:S13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—2011–12 influenza season, United States. MMWR Weekly Rep 2012;61:758–763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power ML, Leddy MA, Anderson BL, Gall SA, Gonik B, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists' practices and perceived knowledge regarding immunization. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:231–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrag SJ, Fiore AE, Gonik B, et al. . Vaccination and perinatal infection prevention practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:704–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kissin DM, Power ML, Kahn EB, et al. . Attitudes and practices of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:1074–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen SA, Power ML, Jamieson DJ, et al. . Practices of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding nonvaccine-related public health recommendations during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:294.e1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SteelFisher GK, Blendon RJ, Bekheit MM, et al. . Novel pandemic A (H1N1) influenza vaccination among pregnant women: Motivators and barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:S116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women–United States, 2012–13 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:787–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination and self-reported reasons for not receiving influenza vaccination among Medicare Beneficiaries aged ≥65 years—United States, 1991–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:1012–1015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert PL, Frick KD, Kane RL, McBean AM. The causes of racial and ethnic differences in influenza vaccination rates among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:517–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo BK. How to improve influenza vaccination rates in the US. J Prev Med Public Health 2011;44:141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy ED, Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, Lu PJ, Singleton JA, Bridges CB. Monitoring seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:S9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Disease Prevention and Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Summary of objectives. Topic area: Immunization and infectious diseases. Healthy People 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives Accessed June26, 2015