Abstract

Objective

To describe morphological and visual outcomes in eyes with angiographic cystoid macular edema (CME) treated with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD).

Design

Prospective cohort study within a randomized clinical trial

Participants

1185 CATT study subjects

Methods

Baseline fluorescein angiogram (FA) images of all CATT study eyes were evaluated for CME. Grading of other characteristics on optical coherence tomography (OCT) and photographic images at baseline and during 2-year follow-up was completed by readers at the CATT Reading Centers. Three groups were created based on baseline CME and intraretinal fluid (IRF) status: 1) CME; 2) IRF without CME; 3) neither CME nor IRF.

Main Outcome Measures

Visual acuity (VA), and total central retinal thickness (CRT) on OCT at baseline, Year 1, and Year 2.

Results

Among 1131 participants having images of sufficient quality for determining CME and IRF at baseline, 92 (8.1%) participants had CME, 766 (67.7%) had IRF without CME, and 273 (24.1%) had neither. At baseline, eyes with CME had: worse mean VA (letters) than eyes with IRF without CME and eyes with neither CME nor IRF (52 vs 60 vs 66 letters, p<0.001); higher mean total CRT (μ) on OCT (514 vs 472 vs 404, p<0.001); and a greater proportion with hemorrhage, retinal angiomatous proliferation lesions, and classic choroidal neovascularization. All groups showed improvement in VA at follow-up; however, the CME group started and ended with the worst VA amongst the three groups. CRT, while higher at baseline for the CME group, was similar at 1 and 2 years follow-up for all groups. More eyes with CME (65.3%) developed scarring during 2 years follow-up compared with eyes with IRF without CME (43.8%) and eyes with neither CME nor IRF (32.5%; p<0.001).

Conclusions

In CATT, eyes with CME had worse baseline and follow-up VA, although all groups showed similar rates of improvement in VA during 2 years follow-up. CME appears to be a marker for poorer visual outcomes in nAMD due to underlying baseline retinal dysfunction and subsequent scarring.

Introduction

Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a pathological condition associated with breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and is characterized by cystic accumulation of extracellular intraretinal fluid in the outer plexiform and inner nuclear layers of the retina.1 On fluorescein angiography (FA), extensive CME takes on a characteristic “petaloid” appearance as cysts extending radially along the Henle nerve fiber layer fill with fluorescein and appear to resemble flower petals.2,3 Some common etiologies for cystoid macular edema include post-surgical edema (Irvine-Gass syndrome), inflammatory uveitis, diabetic retinopathy, vein occlusions, and certain medications.2 It is not common for this pattern of leakage, particularly on FA, to be associated with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD).

The Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) was a multicenter clinical trial of the efficacy of ranibizumab and bevacizumab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD).4,5 In patients receiving anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy, there was improvement in macular swelling demonstrated by improvement in vision and reduced thickness on macular ocular coherence tomography (OCT).4,5 Further study into the morphology of fluid and visual outcomes from the CATT patients showed that while all types of fluid improved with anti-VEGF administration, patients with intraretinal fluid (IRF) on OCT in particular had poorer visual acuity outcomes compared to those with subretinal fluid (SRF) or sub-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) fluid.6 This finding has been substantiated by other work showing IRF to have a strong negative predictive value for functional improvement to anti-VEGF therapy and also combinations of anti-VEGF therapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT).7

The purpose of our study was to examine the presence of the angiographic cystoid macular edema (CME) on FA, as a subtype of IRF, and its association with visual and morphological outcomes within patients enrolled in CATT.

Methods

Study population and procedures

The methodology of the CATT study has previously been described.4,5 Briefly, the CATT enrolled 1185 subjects, 50 years old or greater, from 43 clinical centers across the Unites States who had evidence of previously untreated active nAMD in the study eye. Only one eye per subject, the study eye, was randomized to either intravitreal ranibizumab or bevacizumab on a monthly or as needed (PRN) basis; at week 52, monthly treated patient were re-randomized to either continued monthly therapy or PRN therapy with the same drug. Visual acuity was tested using an electronic visual acuity tester. Color fundus photography (CFP), FA, and OCT were performed at baseline and during 2 years of follow-up by certified technicians and photographers following standardized protocols.8,9

Grading of characteristics on optical coherence tomography (OCT) at baseline or during 2-year follow-up were completed by readers at the CATT OCT Reading Center at Duke University. The OCT readers independently analyzed the scans for morphological characteristics including, but not limited to: presence of IRF, SRF, and sub-RPE fluid; the thickness at the foveal center of the retina; thickness of the subretinal fluid and subretinal tissue complex; and location of fluid in relation to the foveal center.9 Readers at the CATT Photograph Reading Center at the University of Pennsylvania independently examined stereoscopic CFPs and FAs for components of the neovascular lesion, size of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), presence of scar or hemorrhage, and retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP) lesions.8

Baseline FA images of all CATT study eyes were evaluated for CME by one of two physician readers at the CATT Photograph Reading Center. CME was defined as honeycombed patterns of hyperfluorescence surrounding the foveal center, with features of pooling in well-defined foveal and parafoveal spaces. Only CME cases that were very well-defined angiographically, with at least 3 or more “petals” apparent on FA imaging in late frames, confirmed by both readers were included as CME cases in our analyses (Figure 1). Our criteria for angiographic inclusion was fairly strict, and images with <3 petals or leakage that was not at the foveal center (defined as 2.75 disc diameters from the optic nerve10), were excluded from our study. It should be noted that for the purpose of our study, the term “CME” defines the angiographic presence of cysts, where as IRF describes their presence on OCT alone.

Figure 1. Example of subject with angiographic cystoid macular edema.

Color fundus photo of the left eye (left) showing pigmentary changes along with drusen; early frame of fluorescein angiogram (center) showing multiple parafoveal areas of hyperfluorescence corresponding to drusen as well as CNV; late frame of angiogram (right) showing petaloid leakage around the fovea.

An institutional review board associated with each center approved the clinical trial protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations. The CATT was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00593450).

Statistical Analysis

Subjects ineligible for the clinical trial or with ungradable images at baseline were excluded, leaving a total of 1131 patients available for data analysis (Figure 2). Three groups were formed based on baseline CME and IRF status – those with 1) CME; 2) IRF without CME; 3) neither CME nor IRF. The comparison of baseline characteristics, visual outcomes and morphological outcomes were performed using analysis of variance for most continuous measures, and Monte Carlo exact tests for categorical measures. When the distribution of continuous measures was highly skewed, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Linear regression models were used to adjust for the effects of previously identified risk factors for visual acuity and change from baseline in visual acuity at one year.11 All the statistical analysis were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), and a two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Figure 2. Eligibility flow chart for the study of cystoid macular edema.

Results

Baseline characteristics by CME and IRF status

Among the 1131 participants in the data analysis at baseline, 92 (8.1%) had CME, 766 (67.7%) had IRF without CME, and 273 (24.1%) had neither. Baseline demographic features and baseline visual acuity were compared among groups (Table 1). Those with CME or IRF without CME were approximately 2 years older than those with neither CME nor IRF (p<0.001). There was no difference among groups in prevalence of hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and history of stroke/TIA. Patients with CME and IRF had lower rates of diabetes mellitus (16.3% and 15.7% respectively) than patients with neither CME nor IRF (22.7%) (p=0.04). The mean [standard error] visual acuity score (letters) at baseline was worst for those with CME (52.3 [1.52]) compared to those with IRF without CME (59.9 [0.48]) and those with neither CME nor IRF (65.8 [0.66])(p<0.001).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by status of baseline cystoid macular edema (CME) and intraretinal fluid (IRF) (n=1131).

| Characteristic | Category | CME (n=92) |

IRF without CME (n=766) |

No IRF or CME (n=273) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Mean (SE) | 79.5(0.86) | 79.8(0.27) | 77.5(0.46) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Sex | Female, n (%) | 61(66.3) | 490(64.0) | 154(56.4) | 0.06 |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes | Yes, n (%) | 15(16.3) | 120(15.7) | 62(22.7) | 0.04 |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | Yes, n (%) | 64(69.6) | 538(70.2) | 179(65.6) | 0.35 |

|

| |||||

|

History of myocardial

infarction |

Yes, n (%) | 8( 8.7) | 90(11.7) | 37(13.6) | 0.46 |

|

| |||||

|

History of congestive

heart failure |

Yes, n (%) | 4( 4.3) | 50( 6.5) | 18( 6.6) | 0.80 |

|

| |||||

| History of stroke | Yes, n (%) | 6( 6.5) | 45( 5.9) | 18( 6.6) | 0.86 |

|

| |||||

|

History of transient

ischemic attack |

Yes, n (%) | 4( 4.3) | 48( 6.3) | 12( 4.4) | 0.49 |

|

| |||||

| Smoking status | Never, n (%) | 33(35.9) | 340(44.4) | 115(42.1) | 0.24 |

| Current, n (%) | 13(14.1) | 59( 7.7) | 25( 9.2) | ||

| Quit, n (%) | 46(50.0) | 367(47.9) | 133(48.7) | ||

|

| |||||

|

Body mass index

(BMI) |

Age-Adjusted Mean (SE) |

27.2(0.5) | 26.9(0.2) | 27.5(0.3) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

|

AREDS supplement

use |

Yes, n (%) | 49(53.3) | 492(64.2) | 175(64.1) | 0.11 |

|

| |||||

| Lens status, study eye | Phakic, n (%) | 3_4(37.0) | 328(42.8) | 135(49.5) | 0.06 |

|

| |||||

|

Visual acuity score,

study eye (letters) |

Mean (SE) | 52.3(1.5) | 59.9(0.5) | 65.8(0.7) | <0.001 |

P-values are from a one way ANOVA for continuous variables and Monte Carlo exact test for categorical variables.

CNV and OCT characteristics at baseline were also compared by CME and IRF status (Table 2). The proportion with subfoveal CNV was higher in the group with CME (81.5%) than in the other 2 groups (70.5% and 74% respectively), although the differences were not statistically significant (p=0.06). Eyes with neither CME nor IRF were less likely to have hemorrhage associated with the neovascular lesion and were less likely to have RAP lesions than the other groups (p<0.001). Eyes with CME had a higher percentage of classic CNV on FA (52.2%) compared to eyes with IRF without CME (21.1%) and eyes with neither CME nor IRF (16.5%; p<0.001). The mean total central retinal thickness was highest for the CME group (514 [15.8] microns) compared to those with IRF without CME (472[6.68] microns), and those with neither IRF nor CME (404 [10.4] microns, p<0.001). Eyes with CME were less likely to have subretinal or sub-RPE fluid than eyes in the other groups (p<0.05 for all comparisons).

Table 2. Baseline CNV and OCT characteristics by baseline cystoid macular edema (CME) and intraretinal fluid (IRF) status.

| Characteristic | Category | CME (n=92) |

IRF without CME (n=766) |

No IRF or CME (n=273) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNV location | Subfoveal | 75(81.5) | 537(70.5) | 202(74.0) | 0.06 |

| Not subfoveal | 17(18.5) | 225(29.5) | 71(26.0) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Presence of hemorrhage

associated with lesion |

Yes | 62(67.4) | 502(65.7) | 134(49.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 30(32.6) | 262(34.3) | 137(50.6) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

|

| |||||

| Presence of SPED | Yes | 5( 5.4) | 43( 5.6) | 13( 4.8) | 0.87 |

| No | 87(94.6) | 723(94.4) | 260(95.2) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Presence of blocked

fluorescence |

Yes | 21(22.8) | 116(15.1) | 31(11.4) | 0.03 |

| No | 71(77.2) | 650(84.9) | 242(88.6) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| RAP lesions | Yes | 11(12.0) | 108(14.2) | 7( 2.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 81(88.0) | 652(85.8) | 266(97.4) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| CNV type | Classic | 48(52.2) | 167(22.1) | 45(16.5) | <0.001 |

| Minimally classic | 15(16.3) | 129(17.0) | 45(16.5) | ||

| Occult | 29(31.5) | 461(60.9) | 182(66.9) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 9 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Area of CNV, mm2 | Mean (SE) | 1.43(0.14) | 1.87(0.07) | 1.65(0.10) | 0.35 |

| CD or CG | 4 | 89 | 23 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Total area of CNV lesion,

mm2 |

Mean (SE) | 1.90(0.17) | 2.57(0.10) | 2.26(0.14) | 0.11 |

| CD or CG | 1 | 23 | 6 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Central subretinal tissue

complex thickness |

Mean (SE) | 205(14.1) | 209( 6.2) | 206(11.0) | 0.95 |

| CD or CG | 1 | 1 | |||

|

| |||||

|

Central subretinal fluid

thickness |

Mean (SE) | 8.6 ( 3.3) | 31.8( 2.6) | 39.2( 4.5) | 0.001 |

| CD or CG | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Central retinal thickness | Mean (SE) | 300(12.5) | 231(4.01) | 158(2.86) | <0.001 |

| CD or CG | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Total central retinal

thickness |

Mean (SE) | 514(15.8) | 472(6.82) | 404(10.4) | <0.001 |

| CD or CG | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Intraretinal fluid | Present | 91(98.9) | 766(100) | 0(0.00) | N/A |

| Absent | 1(1.09) | 0(0.00) | 273(100) | ||

| CD or CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Subretinal fluid | Present | 67(74.4) | 611(80.4) | 250(91.9) | <0.001 |

| Absent | 23(25.6) | 149(19.6) | 22(8.09) | ||

| CD or CG | 2 | 6 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Sub-retinal pigment

epithelium fluid |

Present | 30(35.3) | 395(55.8) | 129(49.8) | 0.001 |

| Absent | 55(64.7) | 313(44.2) | 130(50.2) | ||

| CD or CG | 7 | 58 | 14 | ||

For continuous variables, p-values are from a one way ANOVA except that the Kruskal Wallis test was used for area of CNV and total area of CNV lesion. For categorical variables, p-values are from the Monte Carlo exact test. CD and CG are not included in statistical tests.

Change in visual acuity and central retinal thickness over time by CME and IRF status

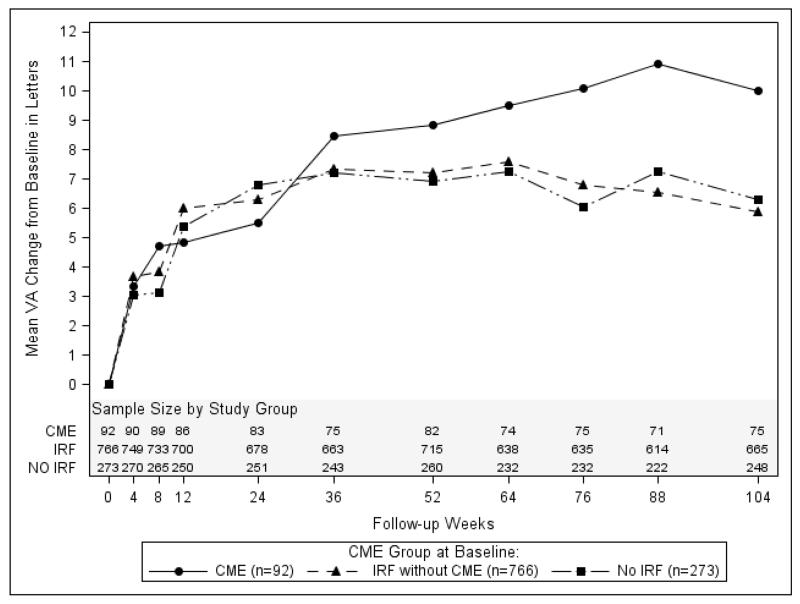

The graph in Figure 3A shows the mean change in visual acuity for each group over the 2 year time period of study. All groups showed considerable improvement in VA after treatment. At week 52, the mean change in visual acuity (letters) was 8.82 in the group with CME, 7.23 in the group with IRF without CME, and 6.91 in the group with neither CME nor IRF (p=0.59). At week 104, the corresponding mean changes were 10.0, 5.89, and 6.31 letters respectively (p=0.13). After adjustment for previously identified risk factors for worse visual acuity (including baseline visual acuity and age), the mean changes in visual acuity for the 3 groups were 7.7, 7.3, and 7.2 (p=0.97) at week 52 and 7.8, 6.0, and 6.8 (p=0.59) at week 104. Those with CME started off with the worst visual acuity, and continued to have the worst visual acuity at each time point through 2 years (Figure 3B; p<0.001 at each point). At week 52, the mean visual acuity (letters) was 61.2 in the group with CME, 67.2 letters in the group with IRF without CME, and 72.7 in the group with neither CME nor IRF (p<0.001). At week 104, the corresponding means were 62.7, 66.1, and 72.4 letters, respectively (p<0.001). After adjustment for previously identified risk factors for worse visual acuity, the mean visual acuities for the 3 groups were 67.7, 68.2, and 68.4 (p=0.94) at week 52 and 67.9, 67.2, and 68.3 (p=0.67) at week 104.

Figure 3A. Change in visual acuity from baseline by cystoid edema and intraretinal fluid status.

Figure 3B. Mean visual acuity over time by cystoid edema and intraretinal fluid status.

Figure 4A shows the mean change in total central retinal thickness (CRT) after treatment for each group. The group with CME had the largest decrease in mean CRT at all points during follow-up. At week 104, the mean decrease in CRT thickness was 241 microns in the group with CME, 175 microns in the group with IRF without CME, and 114 microns in the group with neither CME nor IRF (p<0.001). By 24 weeks and beyond, all groups had similar mean total CRT (Figure 4B).

Figure 4A. Change in total central retinal thickness from baseline by cystoid edema and intraretinal fluid status.

Figure 4B. Total central retinal thickness over time by cystoid edema and intraretinal fluid status.

Study eye features over time by CME and IRF status

Table 3 summarizes morphologic findings over the follow-up period in eyes with CME compared with those without CME at baseline. At both 52 and 104 weeks follow-up, eyes with CME or IRF at baseline had lower percentages of active CNV. At 104 weeks, 24.0% of those with CME had active CNV compared with 26.2% with IRF without CME and 36.0% without IRF or CME (p=0.01). Those with IRF (both CME and non-CME eyes) had the highest rates of geographic atrophy at baseline, 1 and 2 years follow-up (p<0.001 for all time points). While all groups had similar rates of scarring at baseline (p=0.41), 17.3% of CME eyes had scar at the foveal center at 2 years follow-up compared with 6.7% of IRF eyes and 6.9% of eyes with neither CME nor IRF (p<0.001). Among patients treated with PRN for 2 years, the total number of injections was similar among the 3 groups with an adjusted mean of 12.2 in the group with CME, 12.3 in the group with IRF without CME, and 12.5 in the group with neither CME nor IRF (p=0.95).

Table 3. Presence of study eye features over time by cystoid edema (CME) and intraretinal fluid (IRF) status.

| Study Eye Feature | Week | N | CME (n=92) |

IRF without CME(n=766) |

No IRF or CME (n=273) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity, letters, mean (standard error) |

000 | (92, 766, 273) | 52.3 (1.5) | 59.9 (0.5) | 65.8 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| 052 | (82, 715, 260) | 61.2 (2.3) | 67.2 (0.7) | 72.7 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| 104 | (75, 665, 248) | 62.7 (1.9) | 66.1 (0.7) | 72.4 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| Presence of Active CNV Leakage, n (%) |

000 | (92, 766, 273) | 92(100) | 766(100) | 273(100) | 1.00 |

| 052 | (78, 673, 251) | 31(39.7) | 301(44.7) | 132(52.6) | 0.048 | |

| 104 | (75, 637, 242) | 18(24.0) | 167(26.2) | 87(36.0) | 0.014 | |

| Presence of GA at Fovea Center, n (%) |

000 | (92, 766, 273) | 0(0.0) | 1(0.1) | 0(0.) | 1.00 |

| 052 | (79, 690, 254) | 0(0.0) | 20(2.9) | 4(1.6) | 0.22 | |

| 104 | (75, 655, 245) | 5(6. 7) | 46(7.0) | 7(2.9) | 0.048 | |

| Presence of Atrophic Scar / Fibrosis at Fovea Center, n (%) |

000 | (87, 742, 265) | 1( 1.1) | 3( 0.4) | 1( 0.4) | 0.41 |

| 052 | (79, 690, 254) | 10(12.7) | 41( 5.9) | 22( 8.7) | <0.001 | |

| 104 | (75, 655, 245) | 13(17.3) | 44( 6.7) | 17( 6.9) | <0.001 |

P-values are from a one way ANOVA for continuous variables and the Monte Carlo exact test for categorical variables.

Discussion

Previously published results from CATT and other large-scale studies have shown that the presence of intraretinal fluid during follow-up is associated with worse visual acuity while the presence of sub-RPE fluid has relatively little impact on vision and the presence of subretinal fluid is associated with better visual acuity.6,7 Our study examined a specific type of intraretinal fluid – angiographically-present cystoid macular edema – and assessed its impact on visual outcomes in the CATT study patients. We found an association between angiographic cystoid macular edema and visual acuity, but not with change in visual acuity after treatment. After adjustment for other risk factors for visual acuity during follow-up, the visual acuity at 1 and 2 years of follow-up were similar whether IRF or CME were present, so that having CME does not portend post-treatment visual acuity worse than would be expected based on the pretreatment level of visual acuity. In addition, while total central retinal thickness for eyes with CME was greater at baseline than in eyes with IRF without CME and in eyes with neither CME nor IRF, this equalized in all groups at 1 and 2 years follow-up. Despite these findings, CME eyes had the worst visual acuity both at baseline and at 2 years follow-up.

At baseline, the patients with CME, as well as those with IRF were slightly older with lower mean BMI. This raises the possibility that intraretinal fluid and cystoid macular edema may develop in patients with more fragile health. On the other hand, diabetes was less common in patients with CME or IRF. Pseudophakic eyes were more common in the CME group, but not to a statistically significant degree (p=0.06). It is not surprising that CME with IRF had an association with RAP lesions as there is disruption of the inner retina during this process.12 The CME group had a higher proportion of classic CNV, known to be associated with worse visual acuity at presentation.

The reason that the CME group had worse visual acuity at study entry and during follow-up is likely multifactorial. First, our study showed that a high proportion of CME is associated with subfoveal CNV, which has a greater negative impact on vision than occult or non-foveal lesions.13 Second, as mentioned above, associations with hemorrhage and RAP lesions may also lead to further retinal damage and poor visual recovery as these entities are thought to be associated with more “aggressive” nAMD.12 Third, despite there being less active CNV leakage at week 104 in the CME group compared to the others with anti-VEGF therapy, there were higher rates of geographic atrophy and scarring in this group. The proportion with foveal geographic atrophy was similar in eyes with CME and eyes with IRF without CME, but higher than in the eyes with neither CME nor IRF. Formation of scar occurred more often in eyes with CME especially near the fovea. The higher incidence of scarring with CME may be related to the fact that more of these patients have classic CNV which histopathologically corresponds to type 2 CNV located between RPE and neurosensory retina; hence, contraction of this type of CNV leads to RPE loss or hyperplasia. Lastly, CME is a marker for fluid persistence in nAMD, and signifies patients with worse disease at baseline. With the exception of RAP-associated exudation, the exudative process in nAMD typically begins in the outer retina with collection of fluid here first and pervades the inner retina only when the external limiting membrane is broken down, which is related to the amount and time the fluid is present. The damage incurred to the retinal microstructure from this process creates an effect of poor visual acuity that persists despite resolution of the fluid on OCT at weeks 52 and 104 weeks.

In conclusion, CME is associated with worse visual acuity in nAMD. Patients with CME have an improvement in visual acuity after anti-VEGF treatment similar in magnitude to the improvement in other treated eyes, but not enough to compensate for their initially poor visual acuity. While CME is not commonly seen with nAMD, its presence should alert the clinician of poorer visual outcomes and higher rates for eventual atrophy and scarring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by the following grants: R21EY023689, U10EY017823, U10EY017825, U10EY017826, and U10EY017828 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00593450. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: MGM is a consultant for Genentech. GSY is a consultant for Janssen. CAT receives financial funding from Genentech, and Bioptigen; patents from Alcon, and is a consultant for Thrombogenics. GJJ is a consultant for Heidelberg Engineering, Alcon, Neurotech, Roche. No conflicting relationship exists for the other authors.

References

- 1.Quinn CJ. Cystoid macular edema. Optom Clin. 1996;5(1):111–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe G, Cahill MT. Cystoid macular edema. In: Huang D, editor. Vol. 18. Retinal imaging, Mosby Elsevier; 2006. pp. 206–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gass JDM. Current concepts concerning cystoid macular edema. In: Franklin RM, editor. Retina and vitreous: proceedings of the Symposium on Retina and Vitreous. Kugler; Amsterdam: 1993. pp. 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CATT Research Group Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1897–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CATT Research Group Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe GJ, Martin DF, Toth CA, et al. CATT Research Group Macular morphology and visual acuity in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1860–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter M, Simader C, Bolz M, et al. Intraretinal cysts are the most relevant prognostic biomarker in neovascular age-related macular degeneration independent of the therapeutic strategy. Br Jour Oph. 2014;0:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunwald JE, Daniel E, Ying GS, et al. CATT Research Group Photographic assessment of baseline fundus morphologic features in the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2012 Aug;119(8):1634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeCroos FC, Toth CA, Stinnett SS, et al. CATT Research Group Optical coherence tomography grading reproducibility during the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams TD, Wilkinson JM. Position of the fovea centralis with respect to the optic nerve head. Optom Vis Sci. 1992 May;69(5):369–77. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ying GS, Huang J, Maguire MG, et al. CATT Research Group Baseline predictors for one-year visual outcomes with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yannuzzi LA, Freund KB, Takahashi BS. Review of retinal angiomatous proliferation or type 3 neovascularization. Retina. 2008 Mar;28(3):375–84. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181619c55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bressler SB, Bressler NM, Fine SL, et al. Subfoveal neovascular membranes in senile macular degeneration: Relationship between membrane size and visual prognosis. Retina. 1983;3:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jampol LM, Stephanie MP. Macular edema. In: Ryan S, editor. Retina. 2nd ed. Vol. 61. Mosby; 1994. pp. 999–1008. volume 2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.