Abstract

Background

Amotivation, or decisional anhedonia, is a prominent and disabling feature of depression. However, this aspect of depression remains understudied, and no prior work has applied objective laboratory tests of motivation in both unipolar and bipolar depression.

Methods

We assessed motivation deficits using a Progressive Ratio Task (PRT) that indexes willingness to exert effort for monetary reward. The PRT was administered to 96 adults ages 18–60 including 25 participants with a current episode of unipolar depression, 28 with bipolar disorder (current episode depressed), and 43 controls without any lifetime history of Axis I psychiatric disorders.

Results

Depressed participants exhibited significantly lower motivation than control participants as objectively defined by progressive ratio breakpoints. Both the unipolar and bipolar groups were lower than controls but did not differ from each other.

Limitations

Medication use differed across groups, and we did not have a separate control task to measure psychomotor activity; however neither medication effects or psychomotor slowing are likely to explain our findings.

Conclusions

Our study fills an important gap in the literature by providing evidence that diminished effort on the PRT is present across depressed patients who experience either unipolar or bipolar depression. This adds to growing evidence for shared mechanisms of reward and motivation dysfunction, and highlights the importance of improving the assessment and treatment of motivation deficits across the mood disorders spectrum.

Keywords: depression, motivation, progressive ratio, anhedonia, reward, effort

INTRODUCTION

Anhedonia is a cardinal feature of depression, which can occur in the context of unipolar major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Anhedonia may thus represent a critical neurobiological process common across disorders. Defined as decreased interest or pleasure in activities (APA, 2000, 2013), accumulating evidence from affective neuroscience suggests that anhedonia can be differentiated into two distinct processes: the experience of reward (consummatory anhedonia) and motivated behavior to obtain a reward (decisional anhedonia, closely related to anticipatory anhedonia (Der-Avakian and Markou, 2012; Dichter, 2010; Treadway and Zald, 2011). Decisional anhedonia is uniquely associated with disruptions in nucleus accumbens dopamine transmission (Treadway and Zald, 2013). Animal studies show that dopamine depletion leads to selection of low rather than high-effort paths toward reward (Salamone et al., 2007). Clinically, motivational deficits may benefit from specific intervention, indicated by preferential responding to dopaminergic rather than serotonergic antidepressants (Calabrese et al., 2014).

Given such convergent evidence, decisional anhedonia is increasingly studied as a potential intermediate phenotype. One promising objective measure of amotivation is the Progressive Ratio Task (PRT). PRTs originate in the pre-clinical animal literature (Hodos, 1961) and identify the maximum effort a participant is willing to exert by progressively increasing the number of responses required for reward. The maximal effort exerted before choosing not to respond further provides a measure of motivation, referred to as a “breakpoint.” PRTs have been used to study motivation in humans, primarily in the context of addiction. For example, depressed smokers show greater PRT motivation to obtain nicotine than money (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2014) and recreational drinkers show increased PRT motivation for alcohol following depressed mood induction (Willner et al., 1998b). A strength of the PRT is its applicability in both animal models and humans, making this task especially useful for translational investigation (Scheggi et al., 2015; Willner et al., 1998a).

Despite such strengths, to our knowledge only one small pilot study (n = 6) has utilized the PRT to measure decisional anhedonia in patients with clinical depression (Hughes et al., 1985). In that study, PRT motivation increased in most of the treatment-responsive patients, but none of the non-responsive patients. A closely related laboratory effort task, the Effortful Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT; Treadway et al., 2009), has been more widely applied in depression than the PRT itself. Motivation on the EEfRT is reduced in subsyndromal and clinical unipolar depression (Treadway et al., 2012; Treadway et al., 2009), and normalizes with depression remission (Yang et al., 2014). This growing body of translational research suggests that laboratory effort tasks may provide a valuable quantitative index of decisional anhedonia in depression.

Compared to unipolar depression, there has been relatively little laboratory investigation of reward or motivation abnormalities in bipolar depression. While bipolar disorder is distinguished by mania, the same criteria are used to diagnose depressive episodes in unipolar and bipolar disorder, and depression is responsible for the majority of morbidity in bipolar disorder (Post, 2004; Yatham et al., 2005). Consistent with shared mechanisms, behavioral and imaging studies relate blunted reward learning and brain reward responses to depression in both disorders (Hägele et al., 2015; Pizzagalli et al., 2008a; Pizzagalli et al., 2008b; Satterthwaite et al., 2015). However one study reported distinct abnormalities in brain reward response during depression in the two disorders (Chase et al., 2013), and another reported higher trait behavioral activation in bipolar compared to unipolar depression (Quilty et al., 2014). No effort paradigm of any kind has been applied in bipolar depression alone, or across both unipolar and bipolar disorders. Thus the degree to which decisional anhedonia is common to both unipolar and bipolar depression remains unknown.

The current study aims to address this gap in knowledge by applying a brief computerized PRT (Wolf et al., 2014) to patients with unipolar and bipolar depression, as well as healthy comparators. Based on existing evidence for shared anhedonic mechanisms and phenotypes, we hypothesized that depression would be associated with reduced PRT effort across both unipolar and bipolar groups.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

The PRT was administered to 96 adults age 18–60 including 53 participants diagnosed with a current major depressive episode (25 unipolar, 28 bipolar), and 43 controls without any Axis I psychiatric disorders. The depressed and control groups did not differ demographically except for occupational status, nor did the depressed subgroups differ from each other except in medication patterns (Table 1). After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. PRT data was collected as part of a larger study (Satterthwaite et al., 2015; Wolf et al., 2014). On the first study visit, subjects were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Spitzer et al., 1995) and enrolled if they met criteria for a current depressive episode in either major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder (type I or II). The PRT and the Beck Depression Inventory IA (BDI, Beck and Steer, 1993) were performed during a second visit (an average of 12 days after the initial visit). Two subjects included as depressed by diagnostic assessment had subthreshold (<10) BDI scores at the time of PRT; however, excluding them did not change any reported findings. PRT data from 37 controls were included as part of a previous report on amotivation in schizophrenia (Wolf et al., 2014); all control and depressed subjects were tested over approximately the same time period using identical procedures.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Variables

| Variable | CON (n=43) | DEP (n=53) | UNI (n=25) | BIP (n=28) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, years) | 40.2 (11.7) | 37.5 (12.2) | 38.8 (12.8) | 36.4 (11.7) | n.s.a,b |

| Gender (% female) | 53% | 55% | 44% | 64% | n.s.c |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 47% | 57% | 48% | 64% | n.s. |

| Smoke (% yes) | 33% | 25% | 24% | 25% | n.s. |

| Employment (% employed) | 79% | 40% | 44% | 36% | 0.0001 |

| Education (mean, yrs) | 14.7 (2.2) | 15.0 (2.4) | 14.6 (2.5) | 15.4 (2.2) | n.s. |

| Parental Education (mean, yrs) | 13.8 (2.6) | 14.2 (2.8) | 13.5 (2.7) | 14.8 (2.8) | n.s |

| Atypical Antipsychotics (%using)d | 0% | 28% | 8% | 46% | 0.002e |

| Lithium (% using) | 0% | 25% | 8% | 39% | 0.01 |

| Benzodiazepines (% using) | 0% | 25% | 20% | 29% | n.s. |

| Anticonvulsants (% using) | 0% | 23% | 4% | 39% | 0.001 |

| Antidepressants (% using) | 0% | 40% | 60% | 21% | 0.006 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (mean, total) | 2.5 (4.7) | 23.9 (8.5) | 25.2 (8.6) | 22.4 (8.4) | <0.001 |

2-tailed p-values, comparing control(CON) and depressed (DEP) groups. Unipolar (UNI) and bipolar (BIP) subgroups differed only in medication use.

Student’s t test used to compare group means for dimensional variables

Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare proportions for categorical variables

No typical antipsychotics were in use

For medication use variables, p-values reflect UNI vs. BIP comparison with Fisher’s Exact Test

Progressive Ratio Task

Participants performed a computerized PRT to earn money (see detailed description in Wolf et al., 2014). In brief, the task included 7 sets of trials at each of 3 monetary reward levels ($0.50, $0.25, and $0.10). For each individual trial, participants viewed 2 numbers on the screen and identified the larger one by pressing one of 2 keys. Numbers were random between 0 and 1000. The effort (i.e., number of correct responses) required to achieve a reward increased with each successive trial set within a given reward level; no credit was given for incorrect responses. Before each set, the monetary value and number of trials required were presented and the participant chose whether to perform the set; they also could quit a set at any point. When a participant chose not to complete a set, the higher effort sets at that monetary value were skipped and the next set offered was the lowest effort set at the next (lower) monetary value. The PRT was self-paced without trial or task time limits. Participants received their earnings at the end of the study; a maximum of $5.95 could be earned by completing all 21 sets (1454 correct trials).

Data Analysis

The primary PRT outcome was the breakpoint, the maximum effort a participant is willing to exert for a particular reward; higher breakpoints indicate greater motivation. We measured breakpoint in effort trials per-cent (tpc). A single breakpoint was obtained for each participant by averaging across breakpoints for each of three monetary amounts. Within each monetary level, breakpoint was calculated as the geometric mean of the tpc value of the last completed set and the first incomplete set. If no sets were completed, the breakpoint was estimated as the tpc value for the first set; if all sets were completed, then breakpoint was estimated as the tpc value for the last set. As breakpoints were not normally distributed, we examined group differences comparing medians using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum non-parametric test. Breakpoint comparison between depressed and control participants was 1-tailed given our strong a priori hypothesis of reduced motivation in depression; all other analyses were 2-tailed, and a threshold of p < .05 was used throughout.

RESULTS

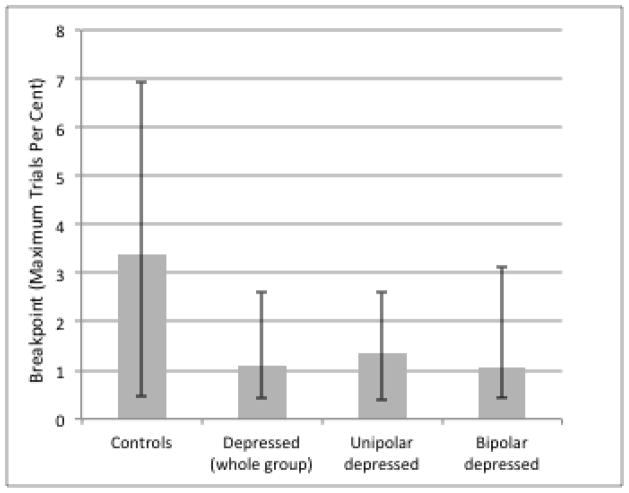

As shown in Figure 1, depressed participants exhibited significantly lower motivation than control participants as objectively defined by progressive ratio breakpoints (median controls = 3.37, median depressed = 1.08, W = 2353, p = 0.024). To examine specificity for bipolar vs. unipolar depression, we compared the subgroups separately to controls and found that both unipolar (median = 1.34, W = 724, p = 0.039) and bipolar groups (median = 1.06, W = 879, p = 0.065) were lower than controls, but did not differ from each other (W = 670, p = 0.94). Breakpoints did not differ according to occupational status across all groups (p = 0.34), nor did use of specific medication classes relate to breakpoints in the depressed subjects (p’s > 0.2). Psychomotor slowing did not explain our results: control and depressed groups did not significantly differ in per-trial median response times (p = 0.13), breakpoints were not significantly correlated with response times (r = −0.14, p = 0.19), and group differences in breakpoint remained significant after adjusting for response times. Although total BDI scores did not correlate significantly with breakpoints in the depressed group, there was evidence of heterogeneity within the BDI in relation to PRT motivation, with anhedonia and amotivation tending to reduce effort, but self-criticism and dysphoria tending to increase effort (see Supplementary Materials).

Figure 1.

PRT motivation by group, measured as the group median of breakpoint (maximum effort trials per cent earned). Upper error bar reflects 75th percentile, lower error bar reflects 25th percentile.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate for the first time that diminished motivation in a laboratory effort task is present across both unipolar and bipolar depression. While unipolar and bipolar depression have very similar clinical phenomenology, it remains unclear to what extent neurobehavioral reward and motivation phenotypes are shared in the depressive phase of the two disorders (Chase et al., 2013; Pizzagalli et al., 2008a; Satterthwaite et al., 2015). Our PRT results are consistent with evidence that both disorders show depression-related hypofunction of motivation circuitry (Hägele et al., 2015; Satterthwaite et al., 2015) and anhedonia-related impairments in reward learning (Pizzagalli et al., 2008a; Pizzagalli et al., 2008b). Our study thus provides novel evidence that decisional anhedonia is present across unipolar and bipolar depression and encourages further efforts to understand shared mechanisms of reward and motivation dysfunction across psychiatric disorders (Foussias et al., 2015; Whitton et al., 2015; Wolf et al., 2014).

Using a PRT to index motivational deficits in animals and humans has wide translational utility. However, despite increasing evidence that decisional anhedonia is an important feature of clinical depression, there has been little research using PRT with clinically depressed patients. Our PRT findings in the unipolar group replicate prior findings of reduced effort in unipolar depression with the EEfRT paradigm (Treadway et al., 2012; Treadway et al., 2009) and provide convergent evidence that decisional anhedonia is an important feature of depression. The EEfRT is likewise adapted from the animal literature (Salamone et al., 1994), but unlike the PRT which uses deterministic effort-reward ratios, the EEfRT incorporates probabilistic rewards. Therefore, the present results argue against the possibility that abnormalities in assessing reward probability are central to the decisional anhedonia seen in depression.

Limitations

Medication use differed across groups, and we did not have a separate control task to measure psychomotor activity. Our results indicate that medication effects or psychomotor slowing are unlikely to explain our findings; however, future studies should include unmedicated samples and a psychomotor control task.

Conclusions

Prior work suggests that behavioral measures of decisional anhedonia improve when depression remits (Hughes et al., 1985; Yang et al., 2014). Such behavioral measures could help match depressed patients to the most appropriate treatments, speeding recovery. Treatments that directly target motivational deficits, such as Behavioral Activation and/or dopaminergic drugs, may be particularly advantageous for those who show motivational deficits on the PRT or similar tasks. Given mixed evidence for antidepressant use in bipolar disorder, including those enhancing dopaminergic function (Bond et al., 2012; Goldberg et al., 2004; Pacchiarotti et al., 2013), objective measures of amotivation could help tailor individualized risk-benefit calculations for using dopaminergic agents in bipolar depression. As antidepressant treatment may cause manic switching, nonpharmacological approaches such as Behavioral Activation may be particularly useful in bipolar depression. Furthermore, effort tasks, potentially in combination with neuroimaging, could provide objective indicators of treatment response. Ultimately, translational measurement of decisional anhedonia may help to parse the heterogeneity within depression, accelerate drug discovery, and improve clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We used a Progressive Ratio Task (PRT) to measure motivation.

We compared motivation on the PRT in patients with bipolar and unipolar depression.

PRT motivation was significantly lower in depressed patients than controls.

PRT motivation did not differ between unipolar and bipolar depressed patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by R01MH101111 and K23MH085096 to DHW, R01MH107703 and K23MH098130 to TDS, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Penn Medicine Neuroscience Center. This paper was prepared with the support (to RH) of the VISN 4 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA.

Footnotes

The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

There were no conflicts of interest related to this project or its authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Wileyto EP, Ashare R, Cuevas J, Strasser AA. Reward and affective regulation in depression-prone smokers. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;76:689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, Weiss M. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Fava M, Garibaldi G, Grunze H, Krystal AD, Laughren T, Macfadden W, Marin R, Nierenberg AA, Tohen M. Methodological approaches and magnitude of the clinical unmet need associated with amotivation in mood disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;168:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW, Nusslock R, Almeida JR, Forbes EE, LaBarbara EJ, Phillips ML. Dissociable patterns of abnormal frontal cortical activation during anticipation of an uncertain reward or loss in bipolar versus major depression. Bipolar Disorders. 2013;15:839–854. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der-Avakian A, Markou A. The neurobiology of anhedonia and other reward-related deficits. Trends in Neurosciences. 2012;35:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS. Anhedonia in unipolar major depressive disorder: a review. Open Psychiatry Journal. 2010;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Foussias G, Siddiqui I, Fervaha G, Agid O, Remington G. Dissecting negative symptoms in schizophrenia: opportunities for translation into new treatments. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2015;29:116–126. doi: 10.1177/0269881114562092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Burdick KE, Endick CJ. Preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole added to mood stabilizers for treatment-resistant bipolar depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:564–566. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hägele C, Schlagenhauf F, Rapp M, Sterzer P, Beck A, Bermpohl F, Stoy M, Ströhle A, Wittchen HU, Dolan RJ. Dimensional psychiatry: reward dysfunction and depressive mood across psychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3662-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134:943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Pleasants CN, Pickens RW. Measurement of reinforcement in depression: a pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1985;16:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(85)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, Nolen WA, Grunze H, Licht RW, Post RM, Berk M, Goodwin GM, Sachs GS. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;11:1249–1262. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Goetz E, Ostacher M, Iosifescu DV, Perlis RH. Euthymic patients with bipolar disorder show decreased reward learning in a probabilistic reward task. Biological Psychiatry. 2008a;64:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M. Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: evidence from a probabilistic reward task. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008b;43:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM. The impact of bipolar depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;66:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilty LC, Mackew L, Bagby RM. Distinct profiles of behavioral inhibition and activation system sensitivity in unipolar vs. bipolar mood disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2014;219:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar A, Mingote SM. Effort-related functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine and associated forebrain circuits. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:461–482. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Cousins MS, McCullough LD, Carriero DL, Berkowitz RJ. Nucleus accumbens dopamine release increases during instrumental lever pressing for food but not free food consumption. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;49:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite TD, Kable JW, Vandekar L, Katchmar N, Bassett DS, Baldassano CF, Ruparel K, Elliott MA, Sheline YI, Gur RC. Common and dissociable dysfunction of the reward system in bipolar and unipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2258–68. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheggi S, Pelliccia T, Ferrari A, De Montis MG, Gambarana C. Impramine, fluoxetine and clozapine differently affected reactivity to positive and negative stimuli in a model of motivational anhedonia in rats. Neuroscience. 2015;291:189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Bossaller NA, Shelton RC, Zald DH. Effort-based decision-making in major depressive disorder: a translational model of motivational anhedonia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:553–558. doi: 10.1037/a0028813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE, Zald DH. Worth the ‘EEfRT’? The effort expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Zald DH. Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: lessons from translational neuroscience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:537–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Zald DH. Parsing anhedonia: translational models of reward-processing deficits in psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:244–249. doi: 10.1177/0963721412474460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton AE, Treadway MT, Pizzagalli DA. Reward processing dysfunction in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2015;28:7–12. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Benton D, Brown E, Cheeta S, Davies G, Morgan J, Morgan M. Depression” increases “craving” for sweet rewards in animal and human models of depression and craving. Psychopharmacology. 1998a;136:272–283. doi: 10.1007/s002130050566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Field M, Pitts K, Reeve G. Mood, cue and gender influences on motivation, craving and liking for alcohol in recreational drinkers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1998b;9:631–642. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DH, Satterthwaite TD, Kantrowitz JJ, Katchmar N, Vandekar L, Elliott MA, Ruparel K. Amotivation in schizophrenia: integrated assessment with behavioral, clinical, and imaging measures. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:1328–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X-h, Huang J, Zhu C-y, Wang Y-f, Cheung EF, Chan RC, Xie G-r. Motivational deficits in effort-based decision making in individuals with subsyndromal depression, first-episode and remitted depression patients. Psychiatry Research. 2014;220:874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham LN, Goldstein JM, Vieta E, Bowden CL, Grunze H, Post RM, Suppes T, Calabrese JR. Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression: potential mechanisms of action. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.