Abstract

Objective

Little is known regarding the role(s) B cells play in obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. The present study utilized a mouse with B cell-specific deletion of Id3 (Id3Bcell KO) to identify B cell functions involved in the metabolic consequences of obesity.

Approach and Results

Diet-induced obese (DIO) Id3Bcell KO mice demonstrated attenuated inflammation and insulin resistance in visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and improved systemic glucose tolerance. VAT in Id3Bcell KO mice had increased B-1b B cells and elevated IgM natural antibodies (Nabs) to oxidation-specific epitopes (OSE). B-1b B cells reduced cytokine production in VAT M1 macrophages, and adoptively transferred B-1b B cells trafficked to VAT and produced NAbs for the duration of thirteen week studies. B-1b B cells null for Id3 demonstrated increased proliferation, established larger populations in Rag1−/− VAT, and attenuated diet-induced glucose intolerance and VAT insulin resistance in Rag1−/− hosts. However, transfer of B-1b B cells unable to secrete IgM had no effect on glucose tolerance. In an obese human population, results provided the first evidence that B-1 cells are enriched in human VAT and IgM antibodies to OSEs inversely correlated with inflammation and insulin resistance.

Conclusions

Nab-producing B-1b B cells are increased in Id3Bcell KO mice and attenuate adipose tissue inflammation and glucose intolerance in DIO mice. Additional findings are the first to identify VAT as a reservoir for human B-1 cells and to link anti-inflammatory IgM antibodies with reduced inflammation and improved metabolic phenotype in obese humans.

Keywords: Obesity, adipose tissue, B cells, IgM, Id3, NAbs

Introduction

Obesity is an epidemic in the Western world, and dramatically increasing rates in developing countries have made it one of the prominent global health concerns of the 21st century. Obesity-induced visceral adipose tissue (VAT) inflammation leads to systemic insulin resistance and glucose intolerance1. While macrophages and T cells have been implicated in this process2, 3, emerging evidence suggests that B cells also modulate obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance.

B cells have been identified in murine and human adipose tissue4-8, and localize to sites of inflammation9. Recently, IgG from diet-induced obese (DIO) mice was shown to drive adipose tissue inflammation and promote systemic insulin resistance4. These pathogenic IgG antibodies were localized in VAT and came from adaptive B-2 B cells – the major B cell subset that differentiate into memory B and plasma cells capable of producing class-switched, high affinity antibodies10. Importantly, IgM antibodies did not impair metabolic function in the same mice, suggesting an isotype-dependent effect.

B-1 B cells, a self-renewing innate B cell population that differ from B-2 cells in response to stimuli and antibody repertoire11, produce a major portion of plasma IgM in uninfected mice12. B-1 B cells are further divided into B-1a and B-1b subsets that have overlapping functions, but exhibit differences in activation and response to infection13-16. Both subsets produce evolutionarily-conserved IgM antibodies, which are termed natural antibodies (NAbs) as they contain few non-templated additions (N-additions), few mutations, and often recognize epitopes expressed on both invading pathogens and dying or damaged self-cells17, 18. In contrast to IgG, B-1-derived IgM NAbs have direct and indirect anti-inflammatory functions19, 20, and are thought to protect in specific instances of diet-induced chronic inflammation20, 21. As B-1 B cells are enriched in omental adipose tissue5, they may be important regulators of VAT function. Despite this, the roles for B-1 B cells and their IgM NAbs in mediating obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance are poorly understood.

While IgM NAbs similar to those derived from murine B-1 B cells are well documented in humans22, 23, identifying a human B-1 B cell has been elusive. Recently however, a subset of circulating B cells in humans was shown to share several functional properties unique to murine B-1 B cells24. However, these cells have yet to be identified outside of the circulation and it is unknown whether, like murine B-1 cells, these B cells are enriched in adipose tissue.

Id3 is a ubiquitously expressed dominant-negative transcription regulator that, along with its binding partners, mediates various stages of B cell development and function25, 26. Mice globally null for Id3 have impaired antigen-specific antibody responses25 and altered levels of circulating IgM27, 28. Recent work from our group has shown a role for Id3 in B cell regulation of diet-induced chronic inflammation28, 29. Additional studies using a mouse model of obesity showed that mice with global deletion of Id3 are protected against diet-induced VAT expansion30. Together, these findings suggest Id3 may be a key factor that links B cell function and obesity. Previous studies of the role of Id3 in atherosclerosis have identified cell type-specific mechanisms whereby Id3 regulates disease pathology31, 32, underscoring the importance of utilizing B cell-specific deletion of Id3 to define mechanisms of B cell regulation in DIO.

In this report, we use mice null for Id3 specifically in B cells (Id3Bcell KO) to test whether B-1 B cells and IgM NAbs mediate the inflammatory and metabolic effects of DIO. We expand upon our murine results with analysis of IgM NAbs and adipose tissue B cells in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Together, results demonstrate that B-1b B cells attenuate the metabolic effects of DIO in an IgM-dependent manner. Furthermore, we identify B-1 B cells in human VAT and provide evidence that specific IgM NAbs negatively associate with insulin resistance in an obese human population.

Materials and methods

Expanded materials and methods can be found in the online supplement.

Results

B cell specific deletion of Id3 attenuates glucose intolerance and VAT insulin resistance in DIO mice

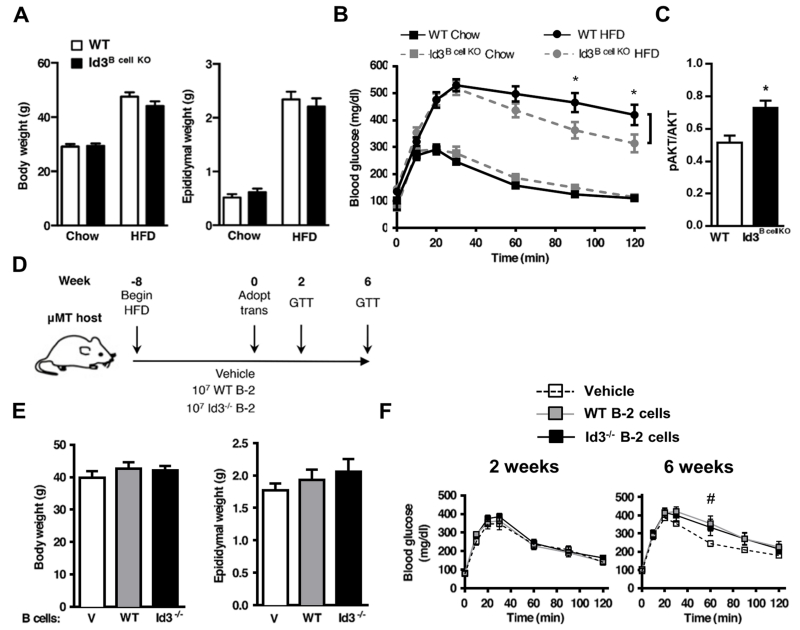

To evaluate whether Id3 expression is important for B cell-mediated effects on DIO, Id3Bcell KO 31, 32 and WT littermates were fed either chow or high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks. As expected, there was a marked increase in body and visceral depot weights in the HFD fed group compared to chow, yet there were no genotype-dependent differences in epididymal adipose tissue mass or body weight (Figure 1A). While B cell-specific loss of Id3 did not completely correct the glucose intolerance due to DIO, Id3Bcell KO mice had significantly improved glucose clearance compared to littermate controls (Figure 1B). There were no genotype-dependent differences in systemic insulin resistance or serum free fatty acid (FFA) levels (Supplemental Figure IA). However, insulin sensitivity as measured by insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation was elevated in omental adipose tissue (Figure 1C). No differences were observed in skeletal muscle or liver (Supplemental Figure IB). Taken together, results suggest that B cells may contribute to tissue-specific effects that may improve metabolic function associated with DIO in an Id3-dependent manner.

Figure 1. Loss of Id3 in B cells attenuates glucose intolerance and adipose tissue insulin resistance in DIO mice.

(A) Body and epididymal adipose tissue weights, and (B) GTT analysis in Id3Bcell KO and WT littermates fed standard chow (WT n=6; Id3Bcell KO n=9) or a HFD (WT n=10; Id3Bcell KO n=14). (C) Insulin-induced AKT phosphorylation in omental fat of WT and Id3Bcell KO littermates fed a HFD (n=3). (D) DIO μMT mice received either an i.p. vehicle (V, n=6) saline injection or adoptive transfer of 107 B-2 cells from DIO WT (n=7) or Id3−/− (n=7) donors and were continued on HFD for six additional weeks. (E) Body and epididymal adipose tissue weights. (F) GTT at two (left panel, representative of two independent experiments) and six (right panel, composite of two independent experiments) weeks post-transfer. Error bars represent ± SEM. *p<0.05, #p<0.05 WT vs. V.

To test whether the attenuated glucose intolerance in the DIO mice stemmed from loss of Id3 in a B-2 cell, either 107 splenic B-2 cells from HFD-primed4 WT or Id3−/− donors, or vehicle control, were injected i.p. into DIO μMT hosts. As μMT mice contain a deletion in the mu heavy chain required for surface BCR expression and essential for both B-1 and B-2 development, these mice lack mature B cells33. Recipient mice were continued on a HFD and tested for glucose tolerance at two and six weeks post-transfer (Figure 1D). No differences in body weight, fat mass (Figure 1E), or B cell engraftment (Supplemental Figure IC) were observed. While all three groups demonstrated similar glucose tolerance at week two (Figure 1F), mice receiving WT B-2 cells had significantly impaired glucose clearance compared to vehicle controls six weeks post-transfer (Figure 1F). This corroborates previous findings4 that B-2 cells impair glucose homeostasis. However, hosts receiving WT and Id3−/− B-2 cells had nearly identical glucose clearance, providing evidence that improved glucose tolerance in Id3Bcell KO mice is not due to loss of Id3 function in a B-2 B cell, and suggesting that other B cell subsets may also modulate HFD-induced glucose intolerance.

DIO Id3Bcell KO mice have increased B-1b B cells, total IgM, and T15-IgM antibodies in adipose tissue

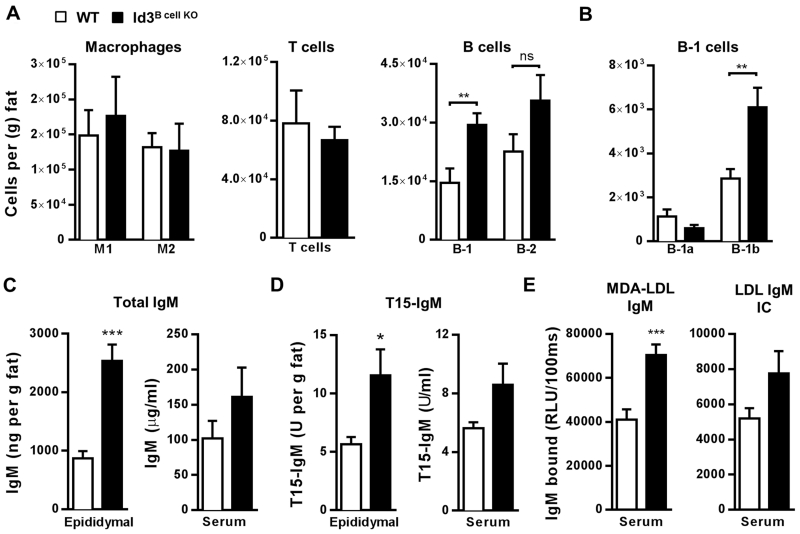

Immune cells within adipose tissue can impact glucose homeostasis in a subset-dependent manner2, 3. Flow cytometry studies in epididymal fat from DIO Id3Bcell KO mice revealed no differences in F4/80+CD206−CD11c+ M1 or F4/80+CD206+CD11c− M2 macrophages34 or total CD3ε+ T cells (Figure 2A). There was a trend toward an increase in B-2 cells, although this change did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, Id3Bcell KO mice had significantly elevated numbers of B-1 B cells within epididymal fat compared to WT littermates (Figure 2A). Further analysis revealed a specific increase in epididymal B-1b, but not B-1a, B cells in DIO Id3B cell KO mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Adipose tissue-specific increases in B-1 cells, total IgM, and T15 natural IgM antibodies in Id3Bcell KO mice with DIO.

(A) Epididymal adipose tissue F4/80+CD206−CD11c+ M1 and F4/80+CD206+CD11c− M2 macrophages (left panel, WT n=6; Id3Bcell KO n=6), CD3ε+ T cells (middle panel, WT n=8; Id3Bcell KO n=11), and B220mid/loCD19hi B-1 and B220hiCD19mid/lo B-2 B cells (right panel, WT n=6; Id3Bcell KO n=8). (B) Epididymal adipose tissue CD5+ B-1a and CD5− B-1b B cells (n=4-6). (C) Total IgM by ELISA in epididymal adipose tissue and serum (n=6). (D) T15-specific IgM by ELISA in epididymal adipose tissue and serum (n=6). (E) Serum MDA-LDL specific IgM and LDL IgM IC (n=13-15). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Among the many known IgM antibodies produced by B-1 B cells, the best studied are members of the T15 NAb family that bind phosphocholine (PC)35, an epitope present on pneumococcal cell membranes as well as on phospholipids of oxidized LDL and apoptotic cells36. These antibodies (T15-IgM or PC-IgM) have anti-inflammatory capacities19, 20, suggesting they may have important regulatory functions within VAT. Epididymal adipose tissue IgM (Figure 2C) and T15-IgM (Figure 2D) levels were elevated in DIO Id3Bcell KO mice compared to WT. Additionally, circulating MDA-LDL IgM and LDL-IgM immune complexes (IC), both associated with reduced inflammation and reduced risk of myocardial infarction in a human population37, 38, were also elevated or showed a trending increase in Id3B cell KO mice (Figure 2E). We observed no variations in circulating or adipose tissue IgG antibodies, including B-2-derived pathogenic IgG2b and IgG2c isotypes (Supplemental Table I). Our findings demonstrate that loss of Id3 in B cells leads to increased B-1 B cell numbers and anti-inflammatory IgM antibodies.

Loss of Id3 in B cells leads to increased T15-IgM production in omental adipose tissue

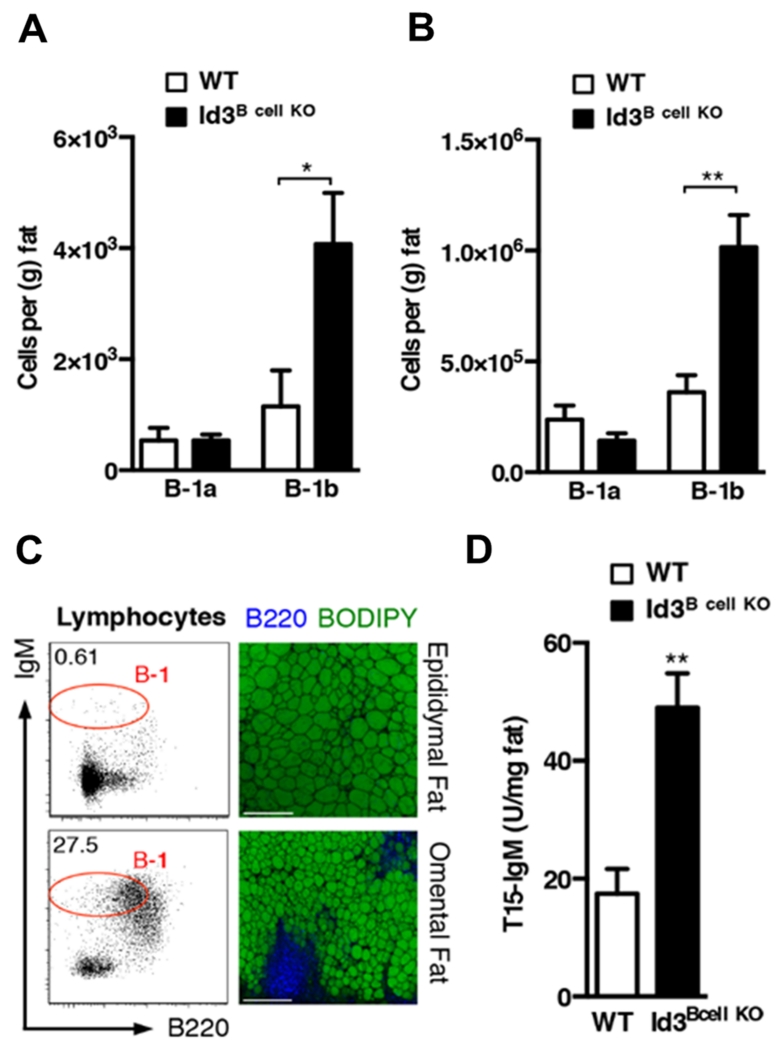

B-1 B cells populate coelomic cavities and can be divided into CD5+ B-1a and CD5− B-1b B cells. While both produce IgM antibodies11, B-1a and B-1b B cells exhibit differences in activation and response to infection13-16, 18, suggesting they may have distinct functions in adipose tissue. Baseline analysis of Id3B cell KO mice revealed that, similar to DIO mice, loss of Id3 in B cells led to a specific increase in B-1b B cell numbers within epididymal (Figure 3A) and omental (Figure 3B) adipose tissue, as well as in peritoneal fluid (Supplemental Figure IIA). No B-1b B cell differences were observed in Id3+/+CD19Cre/+ mice, indicating that population changes were independent of CD19 haplo-insufficiency (Supplemental Figure IIA). Consistent with our initial findings, no differences in B-1a, B-1b, FO, or MZ B cell subsets were identified in the spleens of Id3Bcell KO mice (Supplemental Figure IIB, data not shown).

Figure 3. Loss of Id3 in B cells leads to increased adipose tissue B-1b B cells and IgM secretion in chow-fed mice.

(A) Epididymal and (B) omental adipose tissue B-1a and B-1b B cells in Id3Bcell KO (n=7-8) and WT (n=5) littermates. (C) Representative flow cytometry and 10× confocal microscopy images of murine epididymal (top panels) and omental (bottom panels) adipose tissue. Scale bar=200μm. (D) T15-specific IgM in supernatant of Id3Bcell KO (n=3) and WT (n=4) omental adipose tissue cultures. Error bars represent ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Omental fat refers to the fatty band attached to the greater curvature of the stomach39. Murine and human omental adipose tissue is similar in structure40 and contains B cell-rich clusters of immune cells termed “milky spots.” Enriched B cell numbers help distinguish milky spots from fat-associated lymphoid clusters (FALCS) found in the mesentery that contain high numbers of natural helper cells, but few B cells41. Consistent with previous reports5, substantially more B-1 B cells were found in omental fat than epididymal fat relative to tissue mass (Figure 3A & B), and only omental adipose tissue contained milky spot clusters that stained heavily for the B cell marker B220 (Figure 3C). In addition, omental fat cultured ex vivo from Id3Bcell KO mice produced three-fold more T15-IgM than controls (Figure 3D), providing evidence that PC-specific IgM is produced in omental adipose tissue in proportion to the number of B-1b cells. Together, our findings indicate that Id3 is an important regulator of adipose tissue B-1b B cell population size, and that loss of Id3 leads to significantly more B-1b B cells, and subsequently elevated local T15-IgM NAb production.

Loss of Id3 promotes omental B-1b B cell survival

B-1 B cells survive better than B-2 B cells and have the ability to self-renew, allowing for self-governing population maintenance. To test whether Id3 regulates population maintenance in mature B-1b B cells, we adoptively transferred equivalent numbers of sorted B-1b B cells from WT or Id3Bcell KO donors into B and T cell-deficient Rag1−/− hosts. Rag1−/− mice were used instead of μMT mice because B-1 B cells transferred into μMT mice experience T cell-mediated attack and do not survive42. Both WT and Id3B cell KO B-1b B cells were identified in omental fat (Figure 4A) and peritoneal fluid (Supplemental Figure III) three weeks post-transfer. Id3B cell KO B-1b B cells showed significantly greater engraftment compared to WT in both. No B-1b B cell engraftment was detected in the spleen (Supplemental Figure III), indicating compartment-specific repopulation. Together, our findings suggest that enhanced B-1b B cell numbers in Id3Bcell KO mice is intrinsic to loss of Id3 in mature B-1b B cells.

Figure 4. Id3 regulates B-1b B cell survival.

(A) B-1b B cells recovered in omental fat of Rag1−/− hosts three weeks after adoptive transfer of 80k WT or Id3Bcell KO B-1b B cells (V (vehicle), n=6; WT, n=6 ; Id3Bcell KO, n=5). (B) BrdU incorporation (left) and Annexin V staining (right) of B-1b B cells from WT and Id3Bcell KO mice treated with vehicle (n=3-4) or 40μg LPS (n=5-7). Error bars represent ± SEM. #<0.05 vs V, $<0.05 WT vs Id3B cell KO *p<0.05.

Population maintenance depends on a balance between cell proliferation and cell death, and increased cell numbers can result from defective regulation of either process. To test whether Id3 mediates proliferation or apoptosis in B-1b B cells independent of adoptive transfer, WT and Id3Bcell KO mice were treated with LPS – a rapid B-1b activator43. Mice were then injected with BrdU to label proliferating cells, and B-1b B cells in omental fat were analyzed for proliferation and apoptosis. LPS-activated B-1b B cells in omental adipose tissue displayed no Id3-dependent differences in BrdU incorporation (Figure 4B). However, loss of Id3 in B cells led to lower Annexin V staining (Figure 4B), indicating reduced apoptosis, and suggesting Id3 as an important mediator of B-1b B cell survival.

Loss of Id3 in B cells attenuates HFD-induced inflammation in omental adipose tissue

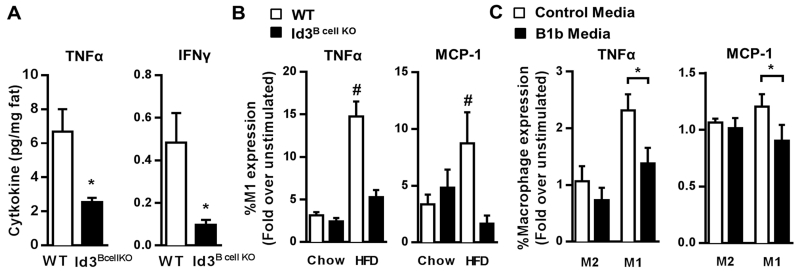

Omental fat of Id3Bcell KO mice contains higher numbers of B-1b B cells and produces more anti-inflammatory T15-IgM NAbs. To determine if loss of Id3 in B cells attenuates HFD-induced adipose tissue inflammation, inflammatory cytokine secretion by omental adipose tissue was evaluated in DIO WT and Id3Bcell KO mice. Indeed, while no differences were observed between chow-fed animals (data not shown), omental fat from DIO Id3Bcell KO mice produced significantly less TNFα and IFNγ compared to diet-matched WT controls (Figure 5A). While recent studies have identified IL-10 as a mechanism by which B-1 B cells limit inflammation, we did not observe differential IL-10 secretion in adipose tissue of Id3B cell KO DIO mice (Supplemental Figure IV).

Figure 5. Reduced adipose tissue inflammation in Id3B cell KO DIO mice and decreased adipose tissue M1 macrophage inflammation after treatment with B-1b-conditioned media.

(A) TNFα (left) and IFNγ (right) ELISA analysis of supernatant of omental adipose tissue cultures from WT and Id3Bcell KO DIO littermates (n=5-7). (B) LPS-induced TNFα (left) and MCP-1 (right) cytokine levels in adipose tissue M1 macrophages from WT and Id3Bcell KO mice fed chow or HFD detected by flow cytometry (n=5-8). (C) LPS-induced intracellular TNFα (left) and MCP-1 (right) cytokine levels in adipose tissue M1 and M2 macrophages detected by flow cytometry. Cells from DIO mice were treated with control media or media conditioned with supernatant from activated WT B-1b B cells (B-1b media) (n=5). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p<0.05, #p<0.05 vs all groups.

DIO is characterized by infiltrating adipose tissue M1 macrophages that produce inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and MCP-1. Therefore, we hypothesized that despite no difference in macrophage number (Figure 2A), pro-inflammatory cytokine production may be reduced in omental M1 macrophages of Id3B cell KO DIO mice. Indeed, M1 macrophages from omental adipose tissue of Id3B cell KO DIO mice lacked the DIO-induced TNFα and MCP-1 expression present in WT M1 macrophages (Figure 5B). We next sought to determine whether secreted B-1b B cell products can attenuate adipose tissue macrophage production of these cytokines. Omental depots from WT DIO mice were treated with conditioned media from control and activated B-1b B cells, and flow cytometry was used to measure LPS-induced TNFα and MCP1 production in adipose tissue macrophages. Results demonstrated that secreted factors from activated B-1b B cells blunted TNFα and MCP-1 production in M1, but not M2, macrophages (Figure 5C). Together, these findings provide evidence that B-1b B cells can play a regulatory role in reducing adipose tissue inflammation.

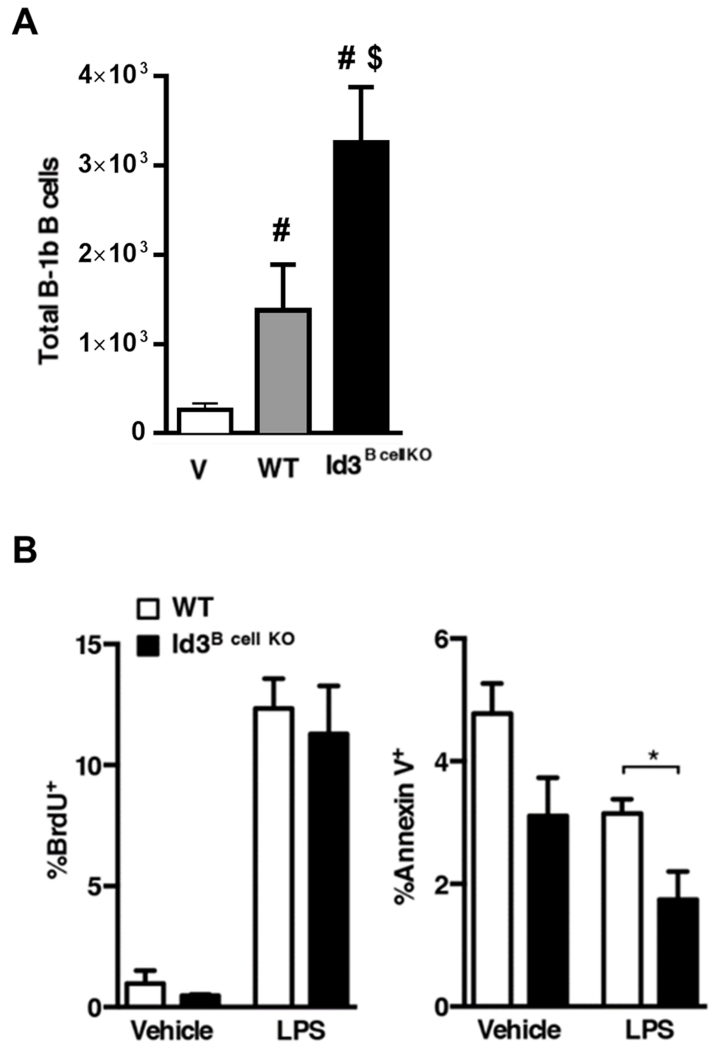

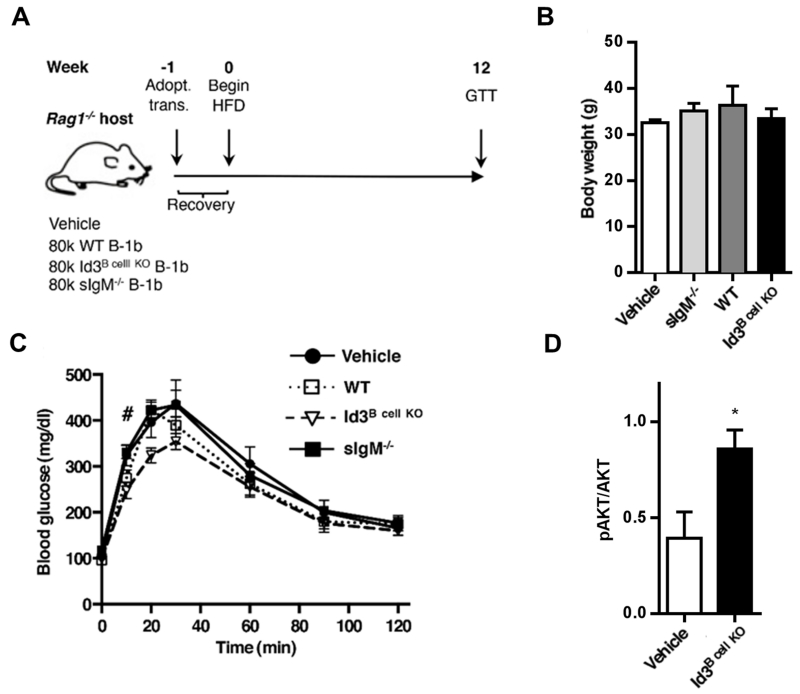

B-1b B cells lacking Id3, but not the ability to secrete IgM, attenuate diet-induced glucose intolerance

Findings in the Id3Bcell KO mouse suggest that improved B-1b B cell survival leads to increased B-1b B cell number and elevated local IgM production that may protect against downstream metabolic dysfunction. To test this, FACS-sorted B-1b B cells from WT, Id3Bcell KO, or sIgM−/− donors were adoptively transferred into Rag1−/− hosts that were then placed on a HFD for 12 weeks (Figure 6A). While B cells from sIgM−/− mice express surface IgM and secrete IgG, they cannot secrete IgM44. Total plasma IgM, LDL IgM IC, and MDA-LDL IgM levels were tested at 2 and 12 weeks after diet initiation (Supplemental Figure V). Antibody levels increased with time, indicating continued B-1b survival and active IgM production through the duration of the experiment. Mice receiving Id3B cell KO B-1b B cells showed elevated total IgM and LDL IgM-IC, but similar levels of MDA-LDL IgM compared to WT. Interestingly, B-2 adoptive transfer hosts showed very low antibody levels, providing evidence that B-1b B cells are major IgM producers. While no body weight differences were observed (Figure 6B), hosts that received Id3Bcell KO B-1b B cells had improved glucose tolerance compared to vehicle controls, and WT hosts showed a trend toward improved glucose clearance (Figure 6C). No differences were seen between hosts that received B-1b B cells from sIgM−/− and vehicle controls (Figure 6C). Additional analysis indicated significantly improved insulin signaling in omental adipose tissue from hosts that received B-1b B cells from Id3B cell KO donors compared to vehicle controls (Figure 6D). These results suggest a role for B-1b B cells in attenuating the metabolic consequences of obesity that is enhanced in the absence of Id3 and is dependent on the ability of the B-1b B cell to secrete IgM NAbs.

Figure 6. B-1b B cells lacking Id3 attenuate diet-induced glucose intolerance, while B-1b B cells unable to secrete IgM have no effect.

(A) Rag1−/− mice received either an i.p. vehicle (V, n=5) saline injection or adoptive transfer of 8.0×104 B-1b B cells from WT (n=4), Id3B cell KO (n=5), or sIgM−/− (n=3) donors. After a recovery week, hosts were placed on a HFD for 12 weeks. (B) Body weight, (C) GTT, and (D) omental insulin signaling of DIO Rag1−/− hosts. #p<0.05 Id3B cell KO vs V, *p<0.05.

PC-IgM NAbs in circulation and within omental adipose tissue of humans negatively correlate with MCP-1

PC-recognizing IgM NAbs derived from B-1 B cells have anti-inflammatory characteristics19, 20. To determine if PC-IgM was associated with a serum marker of inflammation, we measured circulating levels of MCP-1 in a cohort of bariatric surgery patients (cohort 1; 122 patients enrolled between May, 2009 and August, 2010). The baseline clinical characteristics of this cohort are shown in Supplemental Table II. Circulating MCP-1 – a macrophage chemoattractant protein known to be highly predictive of insulin resistance45 – inversely associated with PC-IgM in both the circulation and within omental adipose tissue (Supplemental Table III). Our studies provide evidence that PC-IgM NAbs are present in human omental adipose tissue and are associated with reduced MCP-1.

IgM NAbs and apoB-immune complexes correlate with HDL levels and improved LP-IR scores

Several studies have revealed that in addition to PC-IgM, IgM NAbs directed at other oxidation-specific epitopes associate with reduced inflammation and decreased risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in prospectively followed subjects from the general community37, 38 To determine if other IgM NAbs were associated with metabolic dysfunction, we scored each patient in cohort 1 from 0 (most insulin sensitive) to 100 (most insulin resistant) using an NMR-based Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance (LP-IR) panel. Because NMR has the capacity to measure both lipoprotein size and particle concentration, LP-IR accounts for parameters missed by normal lipid panels and is highly predictive of progressive insulin resistance after multivariate analysis46, 47. In contrast to methods used for measuring beta cell function such as HOMA-IR, LP-IR measurements are not affected by acute changes in glucose or insulin. Thus, LP-IR is reflective of long-term metabolic function and better reflects overall metabolic health. While there was no correlation with LP-IR scores and circulating PC-IgM in this population (data not shown), LP-IR had a significant negative association with IgM apoB immune-complexes (IgM-IC) and a trending inverse correlation with IgM antibodies to MDA-LDL (Table 1). Both IgM-IC and IgM MDA-LDL were positively associated with HDL. In contrast to IgM, no associations were observed with IgG-IC or IgG MDA-LDL. Together, our results provide evidence that IgM NAbs directed at oxidation-specific epitopes may be associated with protective phenotypes in an obese human population, suggesting a role for B-1 B cells in regulating metabolic syndrome in humans.

Table 1.

IgM autoantibodies and apoB-immune complexes correlate with HDL levels and improved LP-IR scores in obese humans (cohort 1).

| Measurement | LP-IR | HDL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Spearman coefficient |

p-value | Spearman coefficient |

p-value | |

| IgM-IC | −0.24 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.0005 |

| IgG-IC | −0.002 | 0.98 | 0.08 | 0.35 |

| IgM MDA-LDL | −0.15 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| IgG MDA-LDL | −0.08 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.85 |

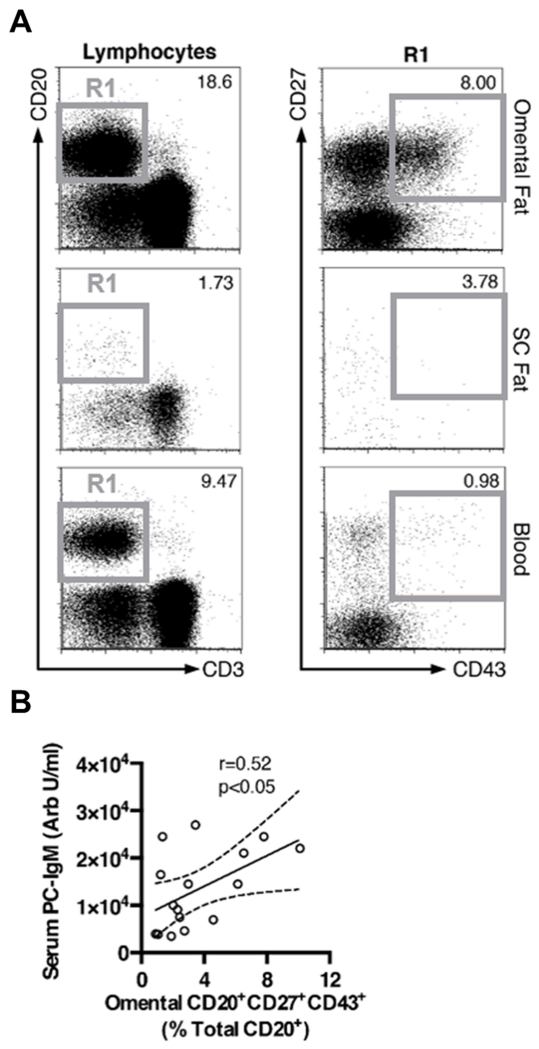

Human omental adipose tissue contains B-1-like cells and PC-IgM

Recently, Griffin et al. identified a subset of circulating B cells (CD20+CD27+CD43+) in humans that share several unique properties of murine B-1 B cells24. To determine if this subset of B-1 B cells are found in human omentum, we performed flow cytometry on sections of omental fat harvested from a second smaller group of patients undergoing bariatric surgery (cohort 2; 16 patients enrolled between October, 2012 and October, 2013). Interestingly, a marked enrichment of B-1 cells was found in omental fat compared to subcutaneous fat or blood in four of 16 patients analyzed. Figureure 7A is a representative flow cytometry plot of the patients whose samples displayed marked enrichment. B-1 cells in omental adipose tissue directly correlated with plasma PC-binding IgM levels (Figure 7B). Together, these findings show for the first time that B-1 B cells are enriched in human omental adipose tissue and the percentage of B-1 cells directly correlates with circulating IgM to PC.

Figure 7. B-1 B cells in human omental adipose tissue correlate with serum PC-IgM levels.

(A) Flow cytometry on omental fat, subcutaneous (SC) fat, and blood from a single patient. (B) Fraction of omental B-1 (CD20+CD27+CD43+) B cells plotted against serum PC-IgM levels in patients from cohort 2 (n=16). Solid line represents Spearman correlation and dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Recent studies have demonstrated subset-specific roles for B cells in both aggravating and regulating the perturbations associated with obesity. Winer and colleagues demonstrated that B-2 B cells promote insulin resistance and glucose intolerance through production of pathogenic antibodies4. Additional studies have shown that sorted splenic B-2 B cells from obese mice secrete more IL-6 and MIP-2 and less IL-10 compared to lean controls48, and circulating B cells (of which the vast majority are B-2) from T2D patients are also skewed toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype after TLR stimulation49. Our adoptive transfers of B-2 B cells provide further evidence that B-2 B cells promote metabolic dysfunction during DIO. In contrast, B-1a B cells were recently shown to protect against the inflammatory and metabolic consequences of DIO through a combination of IgM and IL-10 production50, and B cell-derived IL-10 reduces adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance caused by DIO51, 52. Our findings add to these studies and indicate for the first time a role for B-1b-derived IgM NAbs in attenuating adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity.

Although CD5− B-1b and CD5+ B-1a B cells are sister populations, they have distinct developmental origins53 and functional properties16. While it has long been recognized that B-1a B cells spontaneously produce IgM NAbs against oxidation specific epitopes generated during inflammation and cell death, such as E06/T15 against PC and NA17/E014 against MDA22, the role of B-1b B cells in producing these important antibodies and their impact in DIO is poorly understood. We found Id3B cell KO mice to display an elevated B-1b population at baseline that persisted during obesity progression. Interestingly, we only observed inflammatory and metabolic differences following DIO. It is possible that B-1b B cells function to limit inflammatory processes that become exaggerated in obesity. This explanation fits with our findings that B-1b B cells specifically attenuated M1 macrophage inflammation, as M1 macrophages are rare in lean adipose tissue.

In addition to attenuated obesity-induced inflammation, Id3B cell KO mice showed improved insulin-stimulated pAKT signaling specifically in omental fat, but not in skeletal muscle or liver. As skeletal muscle is the main tissue that accounts for insulin-stimulated glucose disposal54, Id3-mediated B cell effects on insulin signaling in adipose alone may not be sufficient to result in systemic effects. Indeed, we did not observe differences in systemic insulin resistance as measured by ITT in Id3B cell KO mice.

B-1-derived IgM NAbs can reduce inflammation and promote apoptotic cell clearance17, 22, 55; processes that become dysregulated during the progression of obesity39, 56. However, it is currently unclear whether specific IgM antibodies play important roles in mediating the effects of obesity. The well-studied T15 family of PC-IgM NAbs have known anti-inflammatory properties19 and are thought to prevent macrophage lipid uptake and apoptotic cell accumulation in models of atherosclerosis21, 57. However, Shen et al. reported no metabolic effect when PC-IgM was infused into DIO μMT mice50. Interestingly, a partial loss of B-1a B cell attenuation of glucose intolerance was observed when the B-1a B cells could not secrete IgM50. While these seemingly disparate findings could be explained by insufficient amount or localization of the infused antibody, it is likely that other IgM antibodies are needed for the full effect on glucose handling. Notably, our results in mice and humans support this hypothesis as we demonstrated complete loss of the protective effect provided by B-1b B cells when they were unable to secrete IgM. No associations with PC-IgM and insulin sensitivity were found in obese humans, but trending and significant associations between insulin sensitivity and IgM antibodies and immune complexes to other oxidation-specific epitopes were identified. It is of interest that it has recently been shown that IgM to both MDA-LDL and OxLDL epitopes display a remarkably high heritability, in the range of h(2) – 0.6-0.8, suggesting that there may be a strong genetic component to these “anti-inflammatory” innate responses, which may have confounded these association studies58. Together these results suggest that certain IgM clones may play differing roles in mediating inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Identifying these associations is an important first step toward understanding the role IgM antibodies play in obesity-associated metabolic disease.

Much of the knowledge about immune regulation of disease has come from murine studies, and in many cases, the relevance to humans remains to be deciphered. While immunohistochemical analysis has demonstrated B cells within human omental fat7, 8, the lack of a known human B-1 cell equivalent, along with the multiple markers needed to identify subsets and the challenges of performing flow cytometry on human omental adipose tissue had made subset analysis difficult. Recently, a circulating human CD20+CD27+CD43+ B cell with several characteristics similar to murine B-1 B cells was identified24. Here, we demonstrate for the first time using multicolor flow cytometry of human omental fat, that like murine B-1 B cells, CD20+CD27+CD43+ B cells are not only present in omental fat, but in some patients were markedly enriched compared to subcutaneous adipose tissue and blood. Not all omental adipose tissue samples demonstrated this marked enrichment, possibly due to uneven clustering and distribution of milky spots within individual depots, variable sampling at the time of surgery, or because of differences in individual patients, such as the genetic regulation of B-1 cell Nab production implied by the heritability of IgM to oxidation specific epitopes noted above. Nonetheless, the percentage of omental B cells that were CD20+CD27+CD43+ B cells correlated with circulating PC-IgM levels. Our findings add to the known similarities between murine B-1 B cells and human CD20+CD27+CD43+ B cells, and indicate that further analysis of omental adipose tissue may improve our understanding of the role B-1 B cells play in metabolic regulation.

In summary, the present study provides the first evidence that B-1b B cells and the anti-inflammatory IgM NAbs they produce attenuate diet-induced glucose intolerance in mice. Moreover, our findings are the first to identify CD20+CD27+CD43+ B cells and PC-IgM within human omental adipose tissue and show an inverse correlation of specific IgM antibodies with MCP-1 levels and insulin resistance. While much work remains to be done, these results provide evidence that B-1 B cells and their IgM NAbs may be important modulators of inflammation and insulin resistance in human obesity.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

While immuno-regulation has emerged as a critical component of the metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity, functional roles for specific immune subsets in this context remain unclear. In this study, we use a mouse null for the transcription factor Id3 specifically in in B cells to demonstrate a role for innate B-1b B cells and natural IgM antibodies in regulating adipose tissue inflammation, insulin resistance, and systemic glucose intolerance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Furthermore, we identified a recently-discovered human B-1 B cell in visceral adipose tissue of patients undergoing bariatric surgery, and found an inverse association between IgM antibodies and insulin resistance. Results from this study are the first to link B-1b B cells and their IgM antibodies with improved metabolic function and further expand our understanding of the complex interactions between the immune system and metabolic function.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank, Melissa Marshall, Scott Seaman, Lingjin Meng, and Rowena Crittenden for technical advice and assistance; Frances Gilbert, Elizabeth Rexrode, and Anna Dietrich-Covington for coordinating human studies and sample acquisition; Dr. Yuan Zhuang (Duke University) for providing Id3−/− and Id3fl/fl mice, Dr. Timothy Bender for providing CD19Cre and Rag1−/− mice, and Dr. Peter Lobo for providing sIgM−/− mice; Dr. Loren Erickson and Dr. Timothy Bender for advice on B-1 cell biology; and the UVA Flow Cytometry Core for their continued support.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH PO1-HL557;98 (CAM, AMT, ST, JLW), RO1-HL107490 (CAM), AHA Pre-Doctoral Fellowship and 5T32HL007284 (DBH). NIH R01-HL119828, R01-HL093767, HL 088093 (ST, JLW).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- VAT

visceral adipose tissue

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- NAbs

natural antibodies

- PC

phosphocholine

- Id3Bcell KO

B cell-specific Id3 knockout mouse

- HFD

high-fat diet

- MDA-LDL

malondialdehyde-LDL

- LP-IR

lipoprotein insulin resistance

Footnotes

Disclosures: ST and JLW are co-inventors of and receive royalties from patents or patent applications owned by the University of California San Diego on oxidation-specific antibodies.

References

- 1.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:363–374. doi: 10.1038/nm.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YP. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:738–749. doi: 10.1038/nri3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatzigeorgiou A, Karalis KP, Bornstein SR, Chavakis T. Lymphocytes in obesity-related adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2583–2592. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winer DA, Winer S, Shen L, et al. B cells promote insulin resistance through modulation of T cells and production of pathogenic IgG antibodies. Nat Med. 2011;17:610–617. doi: 10.1038/nm.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangel-Moreno J, Moyron-Quiroz JE, Carragher DM, Kusser K, Hartson L, Moquin A, Randall TD. Omental milky spots develop in the absence of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells and support b and T cell responses to peritoneal antigens. Immunity. 2009;30:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffaut C, Galitzky J, Lafontan M, Bouloumie A. Unexpected trafficking of immune cells within the adipose tissue during the onset of obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palming J, Gabrielsson BG, Jennische E, Smith U, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM, Lonn M. Plasma cells and FC receptors in human adipose tissue--lipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of immunoglobulins on adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krist LF, Eestermans IL, Steenbergen JJ, Hoefsmit EC, Cuesta MA, Meyer S, Beelen RH. Cellular composition of milky spots in the human greater omentum: An immunochemical and ultrastructural study. Anat Rec. 1995;241:163–174. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092410204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell ME, Ganley-Leal LM, Mehta A, Bigornia SJ, Mott M, Rehman Q, Farb MG, Hess DT, Joseph L, Gokce N, Apovian CM. B lymphocytes in human subcutaneous adipose crown-like structures. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:1372–1378. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajewsky K. Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature. 1996;381:751–758. doi: 10.1038/381751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgarth N. The double life of a B-1 cell: Self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:34–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thurnheer MC, Zuercher AW, Cebra JJ, Bos NA. B1 cells contribute to serum igm, but not to intestinal iga, production in gnotobiotic ig allotype chimeric mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:4564–4571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoehr AD, Schoen CT, Mertes MM, Eiglmeier S, Holecska V, Lorenz AK, Schommartz T, Schoen AL, Hess C, Winkler A, Wardemann H, Ehlers M. Tlr9 in peritoneal B-1b cells is essential for production of protective self-reactive IgM to control th17 cells and severe autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2011;187:2953–2965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YS, Baumgarth N. Dual role for b-1a cells in immunity to influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3053–3064. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alugupalli KR, Leong JM, Woodland RT, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Gerstein RM. B1b lymphocytes confer T cell-independent long-lasting immunity. Immunity. 2004;21:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas KM, Poe JC, Steeber DA, Tedder TF. B-1a and B-1b cells exhibit distinct developmental requirements and have unique functional roles in innate and adaptive immunity to s. Pneumoniae. Immunity. 2005;23:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binder CJ. Natural IgM antibodies against oxidation-specific epitopes. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(Suppl 1):S56–60. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgarth N, Tung JW, Herzenberg LA. Inherent specificities in natural antibodies: A key to immune defense against pathogen invasion. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Khanna S, Goodyear CS, Park YB, Raz E, Thiel S, Gronwall C, Vas J, Boyle DL, Corr M, Kono DH, Silverman GJ. Regulation of dendritic cells and macrophages by an anti-apoptotic cell natural antibody that suppresses tlr responses and inhibits inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;183:1346–1359. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binder CJ, Horkko S, Dewan A, Chang MK, Kieu EP, Goodyear CS, Shaw PX, Palinski W, Witztum JL, Silverman GJ. Pneumococcal vaccination decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation: Molecular mimicry between streptococcus pneumoniae and oxidized LDL. Nat Med. 2003;9:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nm876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horkko S, Bird DA, Miller E, Itabe H, Leitinger N, Subbanagounder G, Berliner JA, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Monoclonal autoantibodies specific for oxidized phospholipids or oxidized phospholipid-protein adducts inhibit macrophage uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:117–128. doi: 10.1172/JCI4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou MY, Fogelstrand L, Hartvigsen K, Hansen LF, Woelkers D, Shaw PX, Choi J, Perkmann T, Backhed F, Miller YI, Horkko S, Corr M, Witztum JL, Binder CJ. Oxidation-specific epitopes are dominant targets of innate natural antibodies in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1335–1349. doi: 10.1172/JCI36800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouthon L, Nobrega A, Nicolas N, Kaveri SV, Barreau C, Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD. Invariance and restriction toward a limited set of self-antigens characterize neonatal IgM antibody repertoires and prevail in autoreactive repertoires of healthy adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3839–3843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin DO, Holodick NE, Rothstein TL. Human B1 cells in umbilical cord and adult peripheral blood express the novel phenotype CD20+ CD27+ CD43+ CD70. J Exp Med. 2011;208:67–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan L, Sato S, Frederick JP, Sun XH, Zhuang Y. Impaired immune responses and B-cell proliferation in mice lacking the id3 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5969–5980. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugai M, Gonda H, Nambu Y, Yokota Y, Shimizu A. Role of id proteins in b lymphocyte activation: New insights from knockout mouse studies. J Mol Med (Berl) 2004;82:592–599. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayakawa I, Tedder TF, Zhuang Y. B-lymphocyte depletion ameliorates sjogren’s syndrome in id3 knockout mice. Immunology. 2007;122:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doran AC, Lipinski MJ, Oldham SN, et al. B-cell aortic homing and atheroprotection depend on Id3. Circ Res. 2012;110:e1–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipinski MJ, Campbell KA, Duong SQ, Welch TJ, Garmey JC, Doran AC, Skaflen MD, Oldham SN, Kelly KA, McNamara CA. Loss of id3 increases vcam-1 expression, macrophage accumulation, and atherogenesis in ldlr−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2855–2861. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cutchins A, Harmon DB, Kirby JL, Doran AC, Oldham SN, Skaflen M, Klibanov AL, Meller N, Keller SR, Garmey J, McNamara CA. Inhibitor of differentiation-3 mediates high fat diet-induced visceral fat expansion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;32:317–324. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry HM, Oldham SN, Fahl SP, Que X, Gonen A, Harmon DB, Tsimikas S, Witztum JL, Bender TP, McNamara CA. Helix-loop-helix factor inhibitor of differentiation 3 regulates interleukin-5 expression and B-1a B cell proliferation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2771–2779. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld SM, Perry HM, Gonen A, Prohaska TA, Srikakulapu P, Grewal S, Das D, McSkimming C, Taylor AM, Tsimikas S, Bender TP, Witztum JL, McNamara CA. B-1b cells secrete atheroprotective IgM and attenuate atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117:e28–39. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujisaka S, Usui I, Bukhari A, Ikutani M, Oya T, Kanatani Y, Tsuneyama K, Nagai Y, Takatsu K, Urakaze M, Kobayashi M, Tobe K. Regulatory mechanisms for adipose tissue M1 and M2 macrophages in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:2574–2582. doi: 10.2337/db08-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claflin JL, Cubberley M. Clonal nature of the immune response to phosphocholine. Vii. Evidence throughout inbred mice for molecular similarities among antibodies bearing the T15 idiotype. J Immunol. 1980;125:551–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw PX, Horkko S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the t15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL, Miller ER, Sasiela WJ, Szarek M, Olsson AG, Schwartz GG. High-dose atorvastatin reduces total plasma levels of oxidized phospholipids and immune complexes present on apolipoprotein b-100 in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the miracl trial. Circulation. 2004;110:1406–1412. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141728.23033.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsimikas S, Willeit P, Willeit J, Santer P, Mayr M, Xu Q, Mayr A, Witztum JL, Kiechl S. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, prospective 15-year cardiovascular and stroke outcomes, and net reclassification of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2218–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murano I, Barbatelli G, Parisani V, Latini C, Muzzonigro G, Castellucci M, Cinti S. Dead adipocytes, detected as crown-like structures, are prevalent in visceral fat depots of genetically obese mice. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1562–1568. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkosz S, Ireland G, Khwaja N, Walker M, Butt R, de Giorgio-Miller A, Herrick SE. A comparative study of the structure of human and murine greater omentum. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;209:251–261. doi: 10.1007/s00429-004-0446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of t(h)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-kit(+)sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baumgarth N, Jager GC, Herman OC, Herzenberg LA. CD4+ T cells derived from B cell-deficient mice inhibit the establishment of peripheral B cell pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4766–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genestier L, Taillardet M, Mondiere P, Gheit H, Bella C, Defrance T. TLR agonists selectively promote terminal plasma cell differentiation of B cell subsets specialized in thymus-independent responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:7779–7786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boes M, Esau C, Fischer MB, Schmidt T, Carroll M, Chen J. Enhanced B-1 cell development, but impaired IgG antibody responses in mice deficient in secreted IgM. J Immunol. 1998;160:4776–4787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Miyachi H, Maeda S, Egashira K, Kasuga M. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goff DC, Jr., D’Agostino RB, Jr., Haffner SM, Otvos JD. Insulin resistance and adiposity influence lipoprotein size and subclass concentrations. Results from the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Metabolism. 2005;54:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garvey WT, Kwon S, Zheng D, Shaughnessy S, Wallace P, Hutto A, Pugh K, Jenkins AJ, Klein RL, Liao Y. Effects of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes on lipoprotein subclass particle size and concentration determined by nuclear magnetic resonance. Diabetes. 2003;52:453–462. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeFuria J, Belkina AC, Jagannathan-Bogdan M, et al. B cells promote inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes through regulation of T-cell function and an inflammatory cytokine profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215840110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jagannathan M, McDonnell M, Liang Y, Hasturk H, Hetzel J, Rubin D, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE, Ganley-Leal LM, Nikolajczyk BS. Toll-like receptors regulate B cell cytokine production in patients with diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1461–1471. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1730-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen L, Chng MH, Alonso MN, Yuan R, Winer DA, Engleman EG. B-1a lymphocytes attenuate insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2014;64:593–603. doi: 10.2337/db14-0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Takaki S, Nagasaki M, Otsu M, Yamashita H, Sugita J, Yoshimura K, Eto K, Komuro I, Kadowaki T, Nagai R. Adipose natural regulatory B cells negatively control adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2013;18:759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu L, Parekh VV, Hsiao J, Kitamura D, Van Kaer L. Spleen supports a pool of innate-like B cells in white adipose tissue that protects against obesity-associated insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4638–4647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324052111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghosn EE, Yamamoto R, Hamanaka S, Yang Y, Herzenberg LA, Nakauchi H. Distinct B-cell lineage commitment distinguishes adult bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5394–5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121632109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rask-Madsen C, Kahn CR. Tissue-specific insulin signaling, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2052–2059. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang MK, Binder CJ, Miller YI, Subbanagounder G, Silverman GJ, Berliner JA, Witztum JL. Apoptotic cells with oxidation-specific epitopes are immunogenic and proinflammatory. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1359–1370. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bird DA, Gillotte KL, Horkko S, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Witztum JL, Steinberg D. Receptors for oxidized low-density lipoprotein on elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages can recognize both the modified lipid moieties and the modified protein moieties: Implications with respect to macrophage recognition of apoptotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6347–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao F, Schork AJ, Maihofer AX, Nievergelt CM, Marcovina SM, Miller ER, Witztum JL, O’Connor DT, Tsimikas S. Heritability of biomarkers of oxidized lipoproteins: Twin pair study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1704–1711. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.