Abstract

Introduction

Few studies have examined the associations between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and non-medical opioid use (NMOU), particularly in general U.S. samples.

Methods

We analyzed data from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized adults, to examine (1) the relationship between PTSD diagnosis with NMOU, Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU; and (2) the relationship between PTSD symptom clusters with NMOU, Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU. We also explored sex differences among these associations.

Results

In the adjusted model, a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with higher odds of past year NMOU for women and men, but the association was stronger for women. In addition, a PTSD was associated with higher odds of an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for women, but not for men. With regards to the relationship between specific symptom clusters among those with a past year PTSD diagnosis, important sex differences emerged. For women, the avoidance symptom cluster was associated with higher odds of NMOU, an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU, while for men the arousal/reactivity cluster was associated with higher odds of NMOU, an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU. In addition, for men, the avoidance symptom cluster was associated with higher odds of an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, but a lower rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU.

Conclusions

Results add to the literature showing an association between PTSD and NMOU and suggest that PTSD is more strongly associated with substance use for women than men. Further, results based on individual symptom clusters suggest that men and women with PTSD may be motivated to use substances for different reasons.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, opioid use, substance use, U.S. population

1. Introduction

The rate of non-medical opioid use (NMOU; i.e., using prescription opioids for non-medical purposes) in the United States has risen to epidemic levels (Maxwell & Maxwell, 2011). Recent estimates from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) suggest that 14.9% of the adult population (18 and over) in the U.S. endorse lifetime use of NMOU, while 4.7% report NMOU in the past year. In addition to these high rates of use, studies have shown NMOU is associated with harm, such as transitions to heroin use (Jones, 2013), opioid abuse/dependence (Martins et al., 2012; Wu, Woody, Yang, & Blazer, 2010), other illicit substance use (Wu et al., 2010), and death from overdose on non-medical opioids (e.g., Calcaterra, Glanz, & Binswanger, 2013; Cerda et al., 2013). Notably, Calcaterra et al. (2013) found that opioid use, compared to all other illicit substance use, was associated with the largest increase in deaths by overdose in individuals in the Unites States (aged 15–64) between 1999 and 2009. Given these high rates of use and the associated harm, efforts to understand how to prevent NMOU and reduce the negative effects associated with use are important.

Numerous studies aimed at understanding the ‘epidemic’ of NMOU have focused on the relationship between NMOU and psychiatric diagnoses. Using nationally-representative samples, researchers have noted strong associations between NMOU and mood and anxiety disorders (Martins et al., 2012; Martins, Keyes, Storr, Zhu, & Chilcoat, 2009; Wu et al., 2010). Further, using wave 1 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Grella, Karno, Warda, Niv, and Moore (2009) reported that among those with an opioid use disorder (the majority of whom met criteria based on NMOU) the presence of a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder was associated with significantly greater odds of having another substance use disorder diagnosis. Finally, in a study that examined motives for NMOU among opioid dependent, non-treatment seeking adults, over 50% of the sample reported using non-medical opioids to reduce anxiety (Barth et al., 2013).

Interestingly, although several studies have documented the relationship between mood and anxiety disorders and NMOU, few studies have included the assessment of PTSD. This absence of research is notable, as research on heroin and psychiatric diagnoses has suggested that those dependent on heroin with a comorbid diagnosis of PTSD have worse treatment outcomes, are more likely to overdose, and have worse occupational functioning that those without a PTSD diagnosis (Mills & Mills, 2005; Mills, Mills, Teesson, Ross, & Darke, 2007). In addition, studies have shown important differences between heavy users of heroin and heavy users of non-medical opioids among adolescents (Subramaniam & Stitzer, 2009) and adults (Wu, Woody, Yang, & Blazer, 2011), and therefore it is unclear whether the relationship between PTSD and heroin generalizes to NMOU.

The few studies examining NMOU and PTSD have provided some preliminary support for the link between PTSD and NMOU. For example, in a small sample of adolescents seeking treatment for NMOU, Subramaniam and Stitzer (2009) found that 33% of adolescents who were dependent on non-medical opioids met criteria for PTSD. In addition, using the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Becker, Sullivan, Tetrault, Desai, and Fiellin (2008) found a relationship between a single item measuring post-traumatic stress and NMOU in unadjusted models, but not after adjusting for covariates (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, income, education, population density of residence, employment status, work absenteeism, insurance status, Medicaid coverage, arrest/booking for criminal charges). Unfortunately, only one large, epidemiological study to date has examined the association between PTSD diagnosis with NMOU and Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis. Utilizing NESARC-III, Kerridge et al. (2015) found that a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with higher odds of a past-year NMOU among both men and women, while a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with higher odds of an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis among women only, even after adjusting for covariates (i.e., sociodemographic factors, other psychiatric disorders) However, to date, no large, epidemiological studies have examined associations PTSD symptom clusters with NMOU and/or Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis.

A growing number of studies have noted the complexity of PTSD. In particular, substantial sex differences have been noted, suggesting that women may be more likely to experience negative affective states post-trauma exposure (i.e., internalizing), while men may be more likely to externalize their distress (Tolin & Foa, 2006). This sex difference may be meaningful with regards to risk for NMOU related to PTSD as studies have found that women who misuse and/or are dependent on opioids endorse greater coping motives and negative affect than men (Jamison, Butler, Budman, Edwards, & Wasan, 2010; McHugh et al., 2013). Further, across substances, research has indicated that trauma exposure and/or a PTSD diagnosis is associated with greater risk of substance use problems for women than men (Breslau, Davis, & Schultz, 2003; Kachadourian, Pilver, & Potenza, 2014; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995).

In addition to sex differences, there is increasing appreciation for the fact that individuals specific PTSD symptoms clusters are associated with substantial harm, even when symptoms fall below diagnostic threshold (Shea, Vujanovic, Mansfield, Sevin, & Liu, 2010). Further, several researchers have proposed that targeting treatment to individual symptom clusters that are most predictive of problems may prove beneficial for clients struggling with PTSD and harmful sequelae (Joseph et al., 2012; Shea et al., 2010; Sullivan, Fehon, Andres-Hyman, Lipschitz, & Grilo, 2006). Taken together, these findings argue that in addition to examining PTSD diagnosis, more research examining sex differences and specific PTSD symptom clusters is needed.

1.1 Purpose of the Present Study

Given the high prevalence of NMOU in the U.S. population and the paucity of research examining PTSD and NMOU, our primary aim was to examine the relationship between PTSD and NMOU in a nationally representative sample, using data from the second wave of NESARC. In addition, we were interested in examining the associations between PTSD and an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis in the past year and the associations between PTSD and average monthly frequency of NMOU. Our aims were two-fold: (1) we sought to examine whether those with a past year PTSD diagnosis were more likely to report NMOU, an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and greater average monthly frequency of NMOU, and whether these associations varied by sex; and (2) after selecting for those with a past year PTSD diagnosis, we examined the associations between PTSD symptom clusters, consistent with the Fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), with NMOU and an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis in the past year, as well as the average monthly frequency of NMOU, and whether these associations varied by sex.

2 Method

2.1 Study Sample

We analyzed data from wave 2 of NESARC, a nationally representative sample of the U.S. adult, non-institutionalized population (Grant et al., 2009; Grant et al., 2004). Participants in wave 1 of NESARC were surveyed during 2001 – 2002 (N = 43,093). A sub-set of the original sample (N = 39,959) was contacted to participate in wave 2 between 2004 and 2005. The response rate for wave 2 was 86.7%. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV; Grant et al., 2003), a computer-assisted interview, was used to survey participants at both waves. Previous studies have reported good test-retest reliability and validity of DSM-IV diagnoses assessed by the AUDADIS-IV (Grant et al., 2003; Ruan et al., 2008). For a more thorough description of the NESARC methodology, interested readers may consult several other publications (e.g., Grant et al., 2009; Grant et al., 2004).

For analyses examining the relationship between PTSD diagnosis and NMOU, we analyzed all participants from wave 2 (N = 34, 653). We were unable to use wave 1 data as PTSD was not assessed at wave 1 of NESARC. The sample was limited to those with a past year PTSD diagnosis (n = 2,496) for all analyses examining associations between PTSD symptom clusters and NMOU. We further limited our sample to those with a past year PTSD diagnosis because we wanted to examine opioid outcomes and PTSD symptoms that occurred concurrently (i.e., both within the past year), and information regarding the timing of PTSD symptoms (i.e., whether or not the symptoms occurred in the past year) was only recorded for those with a current, past year PTSD diagnosis.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Symptom Clusters

PTSD diagnosis and symptoms were assessed as part of the past year PTSD diagnostic assessment, using the AUDADIS-IV (AUDADIS-IV; Houry et al., 2008). PTSD diagnosis was a dichotomous variable (yes/no) based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. The DSM-IV symptoms were re-categorized into four symptom clusters based on how they are presented in DSM-5: intrusion (formerly re-experiencing); avoidance; negative cognitions/mood; and arousal/reactivity (formerly hyperarousal) (Friedman, 2013). Each respondents’ PTSD symptom cluster score was calculated by dividing the number of symptoms endorsed for a specific cluster by the total number of symptoms for that cluster. For example, if an individual endorsed one out of four symptoms, they had a score of 0.25. This method placed each symptom cluster variable on a consistent range of 0 to 1.

2.2.2 NMOU

Non-medical opioid use was assessed with a question asking individuals if they used painkillers (e.g., Codeine, Darvon, Percodan, Oxycontin) in greater amounts, frequency, or over a longer period of time than a physician prescribed, or without a doctor’s prescription. Individuals who responded affirmatively were then asked follow-up questions about lifetime use, use since the wave 1 interview, and use within the past year. Use within the past-year was coded on a ten-point Likert-type scale that ranged from once a year to everyday.

For the current study, we used two measures of NMOU: a single, dichotomous question asking about NMOU in the past year (yes/no) and a measure of the average frequency of use in a month. For the frequency of use, we recoded the question assessing use within the past year to represent the number of days used in an average month For example, those that indicated that they used everyday received a score of 30, while those that indicated that they used once in the past year received a score of 0.08 (1/12 = 0.08) When individuals endorsed a range of use (e.g., 2 to 3 times per month), the mid-point of the range was used (i.e., 2.5).

2.2.3 Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis

Past year Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis was assessed as part of the substance use and abuse assessment, using the AUDADIS-IV (AUDADIS-IV; Houry et al., 2008). Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis was a dichotomous variable (yes/no) based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.

2.2.4 Covariates

Several variables known to be associated with PTSD (Capaldi & Kim, 2007; Marshall, Jones, & Feinberg, 2011) and NMOU/Opiate use (Martins et al., 2009; Novak, Herman-Stahl, Flannery, & Zimmerman, 2009) were included in the model as covariates: age, education, race/ethnicity, chronic/serious medical conditions, and pain. Seventeen chronic/serious medical conditions were assessed at Wave 2: atherosclerosis, high blood pressure, diabetes, cirrhosis, other liver disease, chest pain/angina, tachycardia, heart attack, heart disease, stomach ulcer, HIV, AIDS, gastritis, arthritis, and stroke. Individuals who endorsed the presence of one or more of these medical conditions in the past year were classified as having a chronic/serious medical condition. Pain was assessed with a single question on the AUDADIS-IV asking respondents about their pain in the last month, with a 5-point, Likert-type scale (i.e., “During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work, including both work outside the home and housework?”). Those who rated pain as interfering 3 and above, which corresponded to ‘moderately’ to ‘extremely’, were classified as having pain.

2.3 Analyses

We conducted all analyses using Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 (StataCorp, 2013), adjusting estimates based on the NESARC survey design. Survey weights were applied to account for oversampling of young adults, African Americans and Hispanics, and to adjust for non-response rates and socio-demographic factors, based on the 2000 Census. Odds ratio estimates and confidence intervals were calculated with logistic regression modeling. Incident rate ratio estimates and confidence intervals were calculated with generalized linear modeling with a negative binomial distribution. To examine our first aim, we analyzed data from the entire NESARC sample, assessing the association between a past year PTSD diagnosis and three opioid outcomes: past year NMOU, past year Opioid Use Disorder, and the average monthly frequency of NMOU. In addition, we examined the interaction between PTSD diagnosis and sex for each of these outcomes, in unadjusted and adjusted models. To examine our second aim, we selected for those with a past year PTSD diagnosis, and calculated unadjusted and adjusted associations between individual PTSD symptom clusters and the three opioid outcomes in multi-variable models. In these multivariable variable model, all PTSD symptom clusters were simultaneously entered in the model. The PTSD symptom cluster variables were standardized for this and subsequent analyses. In addition, we examined how sex interacted with PTSD symptom clusters in the prediction of the three opioid outcomes in unadjusted and adjusted models. For all adjusted models, age, race/ethnicity, education, chronic/serious medical conditions, and pain were included as covariates. When sex was not included in an interaction term, it was also entered as a covariate. For the final models, which included interactions between PTSD symptom clusters and sex, we dropped all non-significant interaction terms.

3. Results

Approximately 2.1% of the total sample had engaged in NMOU in the past year. Descriptive statistics based on NMOU status are found in Table 1. Those that had used non-medical opioids in the past year were more likely to be male (58.7% vs. 47.7%) and white (79.8% vs. 70.8%). The mean age for those with NMOU in the past year was 38.02 (SD = 13.17), which was significantly less than the mean age for those without NMOU (p < .001), With regards to income and employment, those with past year NMOU were less likely to have a household income of $40,000 (49.1% vs. 57.4%), but were more likely to be employed full-time (57.2% vs. 52.9%). PTSD was more common among those with NMOU. Specifically, those with NMOU were more likely to have a lifetime diagnosis (19.8% vs. 9.3%), as well as a diagnosis in the past year (14.6% vs. 6.3%). In addition, NMOU in the past year was associated with a significantly lower age of onset of PTSD (p <.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the overall Wave 2 sample based on NMOU status (N = 34,566)

| No NMOU (97.9%) |

NMOU (2.1%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | p < .001 | ||

| Female | 52.3 | 41.3 | |

| Male | 47.7 | 58.7 | |

| Age | p < .001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 48.37 (17.29) | 38.02 (13.17) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | p < .001 | ||

| White/Caucasian % | 70.8 | 79.8 | |

| Black/African American % | 11.1 | 7.7 | |

| Hispanic % | 11.6 | 8.8 | |

| Other % | 6.5 | 3.8 | |

| Education | p = .178 | ||

| High School/GED or more % | 86.0 | 87.3 | |

| Household Income | p < .001 | ||

| ≥ $40,000 % | 57.4 | 49.1 | |

| Employment | p = .001 | ||

| Full-time employment % | 52.9 | 57.2 | |

| PTSD lifetime diagnosis | 9.3 | 19.8 | p < .001 |

| PTSD past year diagnosis | 6.3 | 14.6 | p < .001 |

| PTSD age of onset | p < .001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34.36 (17.75) | 28.60 (13.42) | |

| Age of onset of opioid use | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.92 (6.34) | ||

| Average monthly NMOU in the past year | -- | 4.68 (8.15) | |

| Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis | -- | 25.5 | |

| Age of onset of Opioid Use Disorder |

|||

| Mean (SD) | 23.24 (4.99) | ||

| Pain | p < .001 | ||

| Moderate to extremely % | 16.9 | 28.6 | |

| Chronic/Serious Medical Conditions |

52.7 | 53.2 | p = .695 |

Note. Non-medical opioid use (NMOU). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). All estimates accounted for the survey design

3.1 Past year PTSD diagnosis and opioid outcomes

In both unadjusted and adjusted models examining past year NMOU, there was a significant interaction between a past year PTSD diagnosis and sex (see Table 2). Inspection of the respective odds ratios in the fully adjusted model indicated that the odds of past year NMOU increased more due to a past year PTSD diagnosis for women (OR = 2.10, 95% CI [1.80, 2.46]; p < .001) than for men (OR = 1.52, 95% CI [1.25, 1.84]; p < .001). With regards to Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, the interaction between PTSD diagnosis and sex was also significant in both the unadjusted and fully adjusted mode (see Table 2). However, inspection of the respective odds ratios in the fully adjusted model indicated that a PTSD diagnosis was associated with greater odds of a diagnosis of an Opioid Use Disorder for women (OR = 2.49, 95% CI [1.87, 3.31]; p < .001), but not for men (p = .268). A past-year PTSD diagnosis was also associated with average monthly frequency of NMOU in the past year in both unadjusted and adjusted models; however, there was no significant sex interaction (see Table 2). In the fully adjusted model, a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with 26% higher rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU (IRR =1.26, 95% CI [1.06; 1.48], p = .008).

Table 2.

Results showing unadjusted and adjusted associations between past year PTSD symptom diagnosis with NMOU, frequency of NMOU, and opioid use disorders with sex interactions

| Unadjusted Models | Adjusted Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMOU | Opioid Use Disorder |

Frequency of NMOU |

NMOU | Opioid Use Disorder |

Frequency of NMOU |

|

| Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

|

| PTSD | 1.15*** | 1.62*** | 1.12*** | 0.74*** | 0.91*** | 0.23** |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 0.56*** | 0.77*** | 0.24 | 0.52*** | 0.74*** | −0.10 |

| PTSD x Sex | −0.29* | −1.12** | NS | −0.33** | −1.25*** | NS |

| Age | --- | --- | --- | −0.06*** | −0.07*** | −0.04*** |

| Education | --- | --- | ||||

| <HS/GED | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| HS/GED+ | −0.05 | −0.21 | −0.32 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| White/Cau | −0.68*** | −0.84*** | −1.02*** | |||

| Black/AA | −0.68*** | −0.84*** | −0.62** | |||

| Hispanic | −0.78*** | −1.41* | −1.28*** | |||

| Other | ||||||

| Pain | ||||||

| No pain | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Pain | 0.90*** | 1.66*** | 1.89*** | |||

| Medical | ||||||

| Conditions | ||||||

| Absent | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Present | 0.53*** | 0.90*** | 1.06*** | |||

Note. AA = African American. All estimates accounted for the survey design. All estimates presented are regression coefficients. Results for NMOU and Opioid Use Disorder are based on logistic regression, while reults for average monthly frequency of NMOU are based on generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.2 PTSD symptom clusters and opioid outcomes

Analyses examining the association between PTSD symptom clusters and the three opioid outcomes (i.e., NMOU, Opioid Use Disorder, average monthly frequency of NMOU) were based on the subsample that had a past year PTSD diagnosis. Approximately 7% of the total wave 2 NESARC sample met diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the past year. Those with a past year diagnosis of PTSD ranged in age from 20 to 90 (M = 45.29, SD = 15.86). These individuals were primarily female (70.0%) and White/Caucasian (70.4%). In addition, the majority had obtained at least a high school diploma or GED (83.5%). With regards to income and employment, 44.6% of those with PTSD had a household income of $40,000 or more and 43.7% were employed full time (35 hours or more) at the time of the survey. With regards to NMOU, 4.8% of those with PTSD reported NMOU in the past year. In addition, 1.4% of those with PTSD met criteria for an opioid use disorder and reported a mean use of 0.26 (SD = 2.31), which is less than a day a month of use. .

Among men with a past year PTSD diagnosis, the unadjusted mean symptom cluster scores were the following: the arousal/reactivity mean was 0.71 (SD = 0.22); the avoidance mean was 0.76 (SD = 0.28); the negative cognitions/mood mean was 0.63 (SD = 0.30); and the intrusion mean was 0.73 (SD = 0.26). Among women with a past year PTSD diagnosis, the unadjusted mean symptom cluster scores were the following: the arousal/reactivity mean was 0.74 (SD = 0.24); the avoidance mean was 0.75 (SD = 0.31); the negative cognitions/mood mean was 0.62 (SD = 0.30); and the intrusion mean was 0.77 (SD = 0.25). Women scored higher than men on arousal/reactivity and intrusion (p < .001); however, the effect size for both differences was not meaningful (ds = −.11 & −.15, respectively). There were no significant sex differences for the avoidance or negative cognitions/mood symptom cluster scores (ps = .520 & .542. respectively).

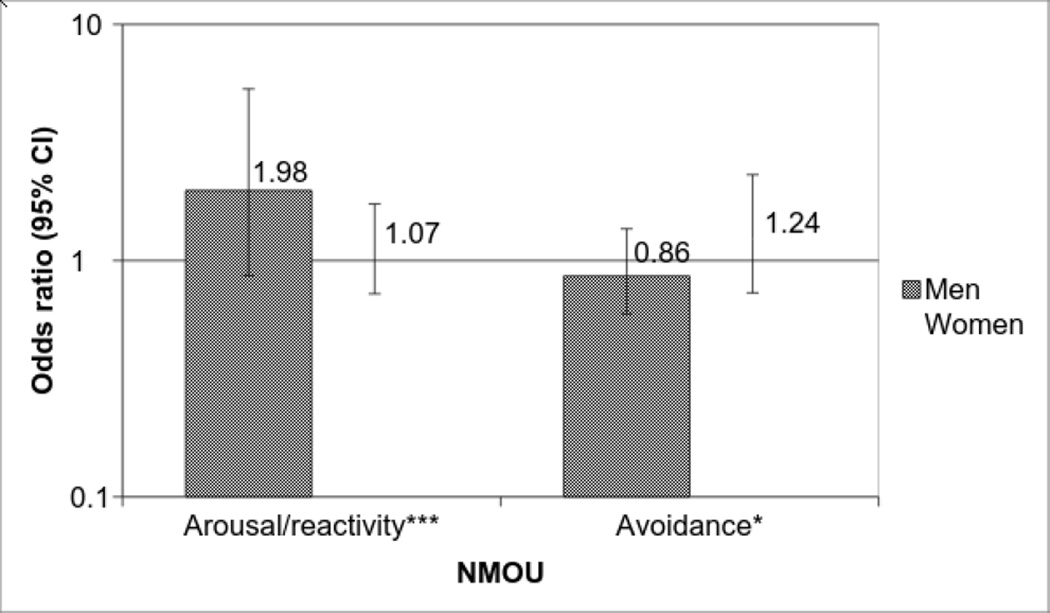

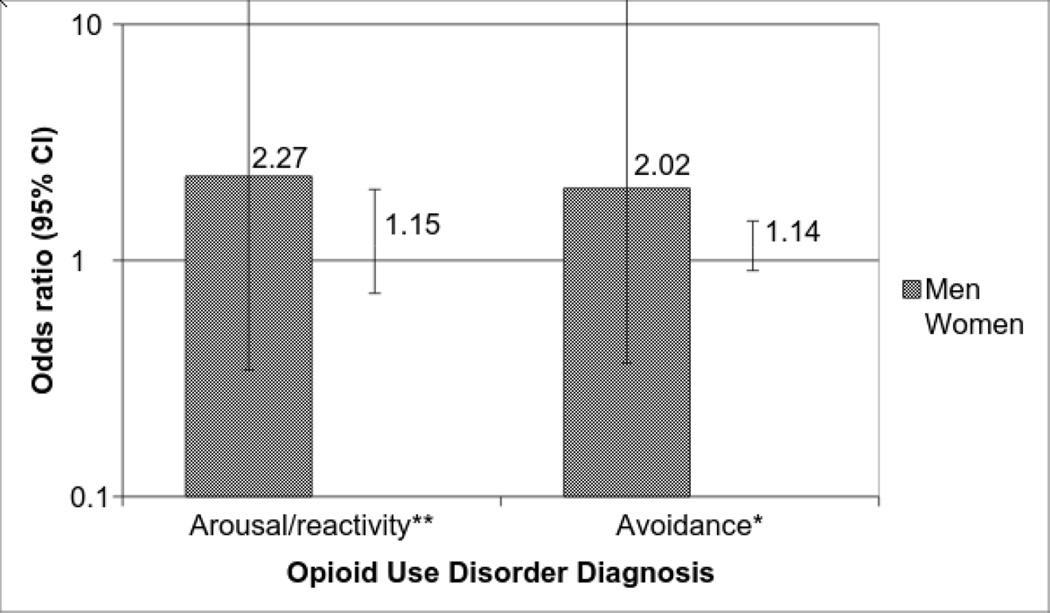

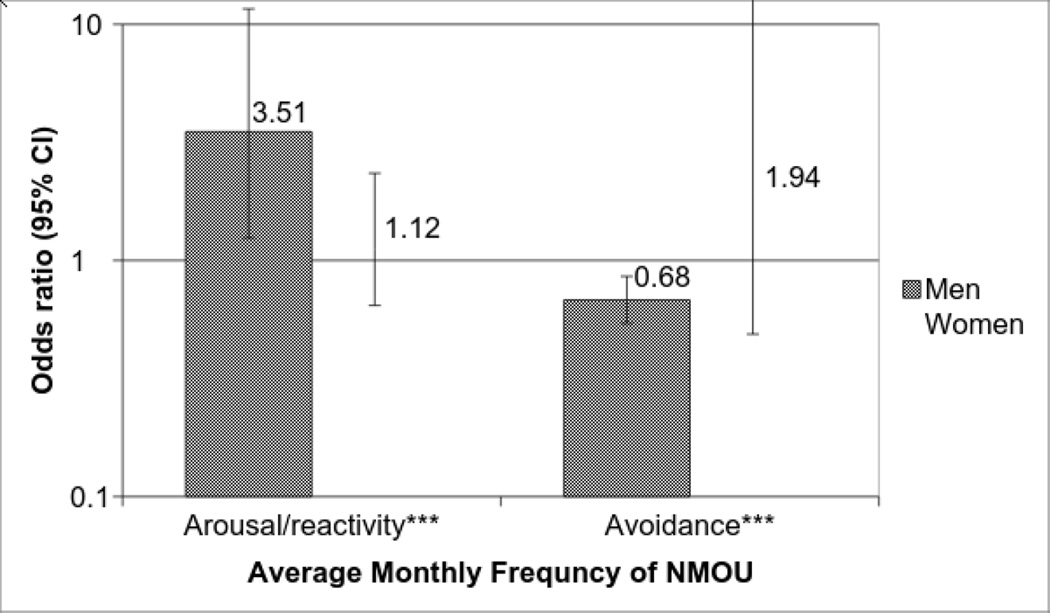

In both the unadjusted and adjusted model examining past year NMOU, there were two significant interactions with PTSD symptom clusters and sex (see Table 3). Specifically, in the fully adjusted model, interactions between sex and past year PTSD symptom clusters were significant for both arousal/reactivity (OR = 1.85, 95% CI [1.51, 2.26]; p < .001) and avoidance (OR = 0.70, 95% CI [0.53, 0.92]; p = .011). As seen in Figure 1, a one standard deviation increase on the arousal/reactivity scale was associated with 98% greater odds of past year NMOU for men (OR = 1.98, 95% CI [1.62; 2.41], p < .001), but not women (p = .454), while a one standard deviation increase on the avoidance scale was associated with 24% greater odds of past year NMOU for women (OR = 1.24, 95% CI [1.01; 1.51], p = .037), but not men (p = .155). Similarly, the fully adjusted model for Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis, revealed significant interactions between sex and the arousal/reactivity symptom cluster (OR = 1.97, 95% CI [0.95; 1.39], p = .003), as well as sex and the avoidance symptom cluster (OR = 1.78, 95% CI [1.04; 3.04], p = .036). However, as seen in figure 2, a one standard deviation increase on both the arousal/reactivity and avoidance scales were associated with over a 100% higher odds of having an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for men (OR = 2.27, 95% CI [1.45; 3.54], p < .001; OR = 2.02, 95% CI [1.28; 3.21], p = .003, respectively), while a one standard deviation increase in the avoidance symptom cluster scale was only weakly associated with higher odds of having an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for women (OR =1.14, 95% CI [1.04; 1.25], p = .007). There was not a significant association between arousal/reactivity scale and an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for women (p = .143). Lastly, in the fully adjusted model examining average monthly frequency of NMOU, there were again significant sex interactions for the arousal/reactivity symptom cluster (IRR = 3.12, 95% CI [2.34; 4.17], p < .001) and the avoidance symptom cluster (IRR = 0.35, 95% CI [0.24; 0.51], p < .001). Figure 3 illustrates the respective IRRs for men and women. A one standard deviation increase on the arousal/reactivity symptom cluster scale was associated with a 251% higher rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU for men (IRR = 3.51, 95% CI [3.06; 4.03], p < .001), but not for women (p = .342). Conversely, a one standard deviation increase on the avoidance symptom cluster scale was associated with a 94% higher rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU for women (IRR = 1.94, 95% CI [1.34; 2.80], p = .001)., while for men, a one standard deviation increase on the avoidance symptom cluster scale was associated with 32% lower rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU (IRR = 0.68, 95% CI [0.58; 0.78], p < .001).

Table 3.

Results showing unadjusted and adjusted associations between past year PTSD symptom clusters with NMOU, frequency of NMOU, and opioid use disorders with sex interactions

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMOU | Opioid Use Disorder |

Frequency of NMOU |

NMOU | Opioid Use Disorder |

Frequency of NMOU |

|

| Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

Main effects with interactions |

|

| Arousal/reactivity | 0.20* | 0.33** | 1.37*** | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Avoidance | 0.28** | 0.21*** | 0.35** | 0.21* | 0.13** | 0.66** |

| Intrusion | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.40** | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Negative cognitions/mood |

−0.09 | 0.44*** | −0.28*** | −0.10 | 0.42*** | −0.38*** |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 0.02 | −1.29*** | 2.11*** | −0.35 | −2.67*** | −0.20 |

| Sex x A/R | 0.39*** | NS | NS | 0.62*** | 0.68** | 1.14*** |

| Sex x AV | −0.28* | 0.59* | NS | −0.36* | 0.58* | −1.05*** |

| Sex x IN | NS | NS | −1.16*** | NS | NS | NS |

| Sex x NC/M | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Age | --- | --- | --- | −0.07*** | −0.08*** | −0.10*** |

| Education | ||||||

| <HS/GED | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| HS/GED+ | 0.26 | −0.27 | −0.53 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White/Cau | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Black/AA | −0.37* | −0.91*** | −0.36*** | |||

| Hispanic | −0.38*** | −1.32*** | 0.38** | |||

| Other | −0.21 | −0.73 | −1.34* | |||

| Pain | --- | --- | --- | |||

| No pain | Ref. | Ref. | Ref.. | |||

| Pain | --- | --- | --- | 1.15*** | 1.24*** | 1.50*** |

| Medical Conditions. |

||||||

| Absent | --- | --- | --- | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Present | 0.58*** | 0.68*** | 1.38*** | |||

Note. A/R = arousal/reactivity; AV = avoidance; IN = intrusion; NC/M = negative cognitions/mood; AA = african american. All estimates accounted for the survey design and selected for those with a past year PTSD diagnosis. The symptom cluster variables were standardized prior to analyses. Unadjusted estimates were adjusted for all PTSD symptom clusters and adjusted estimates included all PTSD symptom clusters and covariates. Results for NMOU and Opioid Use Disorder are based on logistic regression, while results for average monthly frequency of NMOU are based on generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Significant interactions between PTSD symptom clusters and sex, associated with past year NMOU, among those with a past year PTSD diagnosis. Odds ratios represent changes in odds associated with a 1 SD increase for PTSD symptom cluster score. Estimates accounted for the survey design and were adjusted for other PTSD symptom clusters (re-experiencing and emotional numbing), age, education, race/ethnicity, chronic/serious medical conditions, and pain.

*p < .05. ***p <.001.

Figure 2.

Significant interactions between PTSD symptom clusters and sex, associated with past year Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, among those with a past year PTSD diagnosis. Odds ratios represent changes in odds associated with a 1 SD increase for PTSD symptom cluster score. Estimates accounted for the survey design and were adjusted for other PTSD symptom clusters (re-experiencing and emotional numbing), age, education, race/ethnicity, chronic/serious medical conditions, and pain.

*p < .05. **p <.01.

Figure 3.

Significant interactions between PTSD symptom clusters and sex, associated with average monthly frequency of NMOU in the past year among those with a past year PTSD diagnosis. Incident rate ratios represent changes in rate of use associated with a 1 SD increase for PTSD symptom cluster scores. Estimates accounted for the survey design and were adjusted for other PTSD symptom clusters (re-experiencing and emotional numbing), age, education, race/ethnicity, chronic/serious medical conditions, and pain.

***p <.001.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study provide strong support for the relationship between PTSD and NMOU. In a nationally representative sample, we found that a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with an over two-fold increase in odds of past year NMOU for women and a 52% increase in the odds of past year NMOU for men. In addition, we found that a past year PTSD diagnosis was associated with a higher rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU for both men and women. Further, our results indicate that PTSD was associated with an over two-fold increase in the odds of a past year Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for women, while it was not associated with any increase in odds for men. Overall, our findings suggest that a diagnosis of PTSD presents a greater liability for NMOU and Opioid Use Disorder for women. In addition, we found sex differences with respect to PTSD symptom clusters and NMOU; this is important as it suggests that the pathway from PTSD to NMOU may be different for men and women.

Research examining the impact of PTSD on heroin use has reported high-comorbidity between PTSD and heroin use (Cottler, Compton, Mager, Spitznagel, & Janca, 1992; Mills et al., 2005; Tull, Gratz, Aklin, & Lejuez, 2010), which can further complicate treatment for addiction (Mills & Mills, 2005; Mills et al., 2007). Although high rates of PTSD have been reported in a clinical sample receiving treatment for NMOU (Subramaniam & Stitzer, 2009), this is one of two studies to show that a PTSD diagnosis is associated with greater odds of NMOU and an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis in a nationally representative sample, even after accounting for self-reported pain and chronic/serious medical conditions. Given the comorbidity between PTSD and chronic pain (Beck & Clapp, 2011), our results suggest that screening for a PTSD diagnosis may be useful in understanding risk for misuse and abuse of prescription opioids among patients being prescribed opioids. Screening for PTSD may be particularly important for women as our results indicated that PTSD increased the risk for NMOU and Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis for women more so than men. Further, studies have found that women dependent on opioids are more likely to receive opioids through a legitimate prescription, while men are more likely to have obtained medication through illicit means (Back, Payne, Simpson, & Brady, 2010; McHugh et al., 2013), which suggests that careful screening and early intervention for women during medical visits has the potential to reduce rates of NMOU.

In multivariable analyses, the avoidance and arousal/reactivity symptom clusters emerged as having the strongest associations with opioid outcomes. Specifically, for women, the avoidance symptom cluster scores were associated with higher odds of NMOU, an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU, while for men, the arousal/reactive symptom cluster scores were associated with higher odds of NMOU, an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, and average monthly frequency of NMOU. In addition, for men the avoidance symptom cluster scores were associated with higher odds of an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, but lower rate of average monthly frequency of NMOU.

For women, these results suggest that NMOU and abuse may be motivated by a desire to avoid trauma-related stimuli and therefore reduce negative affect and distress. Indeed, Back, Lawson, Singleton, and Brady (2011) reported that in a sample of non-treatment seeking individuals who were currently dependent on non-prescription opioids, women were more likely than men to report using prescription opioids to reduce negative affect and interpersonal distress. Similarly, in a large clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence, McHugh et al. (2013) reported that women endorsed greater coping motives than men. Together, these results suggest that women’s NMOU and abuse may be a form of self-medication in order to avoid or ameliorate negative emotional stimuli, such as trauma.

Results suggest that men may also be engaging in NMOU as a form of self-medication. For men, non-medical opioid use and abuse may be more motivated by a desire to numb or cope with heightened physiological arousal, such as increased anger, exaggerated startle response and difficulty sleeping. In a review on sex differences, Olff, Langeland, Draijer, and Gersons (2007) noted that arousal/reactivity has been hypothesized to be of greater importance for men than women in the development of PTSD, as men have a greater tendency to respond to stress with heightened arousal than women (for a review, see Taylor et al., 2000). Further, Schell, Marshall, and Jaycox (2004) found that arousal/reactivity had the most significant influence on the course of PTSD in a largely male sample, suggesting that arousal/reactivity may be among the most distressing symptoms for men. Consequently, men’s greater sensitivity and distress when faced with heightened arousal/reactivity symptoms may lead to their desire to self-medicate through NMOU. However, given the association between avoidance symptom cluster scores and higher odds of an Opioid Use Disorder diagnosis, it is likely that avoidance of trauma-related stimuli may still play a role in the development of problems related to NMOU.

Several treatments are recommended for the treatment of PTSD and comorbid substance use disorders (Foa, Keane, Friedman, & Cohen, 2008). Although these treatments have shown improved outcomes on both PTSD and substance use disorders, there is a substantial minority that do not respond, particularly with regards to substance use (for a review, see Najavits & Hien, 2013). Results of the present study suggest that it may be beneficial to target treatment to specific symptom clusters in order to improve outcomes for substance use disorders.

4.1 Limitations

There are several limitations that merit discussion. First, the NESARC design prohibited us from examining how sub-diagnostic symptoms relate to NMOU. In future studies, it would be important to examine whether symptoms of avoidance and arousal/reactivity are also associated with NMOU among those who do not meet full criteria for PTSD. Second, given the cross-sectional design, it is unclear whether PTSD symptoms precede substance use or vice versa. Prospectively designed studies, as well as studies using ecological momentary assessment will be important to determine the direction of the relationship. Finally, although we attempted to control for pain in analyses, our measure of pain only assessed self-reported pain in the last month, rather than the past year. This difference in the timing of the assessment may have led to misclassification for some respondents.

4.2 Conclusion

These limitations notwithstanding, this study improves our understanding of the relationship between PTSD and NMOU in a nationally representative sample. Further, results add to the literature suggesting that PTSD confers greater risk for substance use for women. Our findings highlight the importance of examining individual symptom clusters and their relationship to NMOU, which suggests that there may be unique pathways to NMOU and abuse for men and women.

References

- Back SE, Lawson KM, Singleton LM, Brady KT. Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(8):829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, Brady KT. Gender and prescription opioids: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(11):1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.018. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth KS, Maria MMS, Lawson K, Shaftman S, Brady KT, Back SE. Pain and motives for use among non-treatment seeking individuals with prescription opioid dependence. American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22(5):486–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Clapp JD. A different kind of comorbidity: Understanding posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Psychological Trauma. 2011;3(2):101–108. doi: 10.1037/a0021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: Psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94(1–3):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. POsttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcaterra S, Glanz J, Binswanger I. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999–2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK. Typological approaches to violence in couples: a critique and alternative conceptual approach. Clinical Psychology Reviews. 2007;27(3):253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Cerdá Y, Ransome K, Keyes K, Koenen M, Tracy K, Galea Prescription opioid mortality trends in New York City, 1990–2006: Examining the emergence of an epidemic. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Janca A. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):664–670. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ. Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: getting here from there and where to go next. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(5):548–556. doi: 10.1002/jts.21840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Niv N, Moore AA. Gender and comorbidity among individuals with opioid use disorders in the NESARC study. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(6–7):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.002. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Rhodes KV, Kemball RS, Click L, Cerulli C, McNutt LA, Kaslow NJ. Differences in female and male victims and perpetrators of partner violence with respect to WEB scores. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(8):1041–1055. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison RN, Butler SF, Budman SH, Edwards RR, Wasan AD. Gender Differences in Risk Factors for Aberrant Prescription Opioid Use. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11(4):312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002–2004 and 2008–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, McFall M, Saxon AJ, Chow BK, Leskela J, Dieperink ME, Beckham JC. Smoking intensity and severity of specific symptom clusters in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(1):10–16. doi: 10.1002/jts.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachadourian LK, Pilver CE, Potenza MN. Trauma, PTSD, and binge and hazardous drinking among women and men: Findings from a national study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;55(0):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.018. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Ruan WJ, Hasin DS. Gender and nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions - III. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;156:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.026. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. POsttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Jones DE, Feinberg ME. Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: an integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(5):709–718. doi: 10.1037/a0025279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, Blanco C, Zhu H, Storr CL. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: Longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(6):1261–1272. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Keyes KM, Storr CL, Zhu H, Chilcoat HD. Pathways between nonmedical opioid use/dependence and psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(1–2):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.019. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J, Maxwell The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: A perfect storm. Drug and alcohol review. 2011;30(3):264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, DeVito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, Potter JS, Greenfield SF, Weiss RD. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Mills The Costs and Outcomes of Treatment for Opioid Dependence Associated With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):940–945. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Mills M, Lynskey M, Teesson J, Ross S, Darke Post-traumatic stress disorder among people with heroin dependence in the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS): prevalence and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Mills M, Teesson J, Ross S, Darke The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on treatment outcomes for heroin dependence. Addiction. 2007;102(3):447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Hien D. Helping vulnerable populations: a comprehensive review of the treatment outcome literature on substance use disorder and PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(5):433–479. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak SP, Herman-Stahl M, Flannery B, Zimmerman M. Physical pain, common psychiatric and substance use disorders, and the non-medical use of prescription analgesics in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1–2):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BP. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(2):183. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN, Jaycox LH. All symptoms are not created equal: the prominent role of hyperarousal in the natural course of posttraumatic psychological distress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(2):189. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Vujanovic AA, Mansfield AK, Sevin E, Liu F. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and functional impairment among OEF and OIF National Guard and Reserve veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(1):100–107. doi: 10.1002/jts.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Tx: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam GA, Stitzer MA. Clinical characteristics of treatment-seeking prescription opioid vs. heroin-using adolescents with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101(1–2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.015. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Fehon DC, Andres-Hyman RC, Lipschitz DS, Grilo CM. Differential relationships of childhood abuse and neglect subtypes to PTSD symptom clusters among adolescent inpatients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(2):229–239. doi: 10.1002/jts.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(6):959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL, Aklin WM, Lejuez CW. A preliminary examination of the relationships between posttraumatic stress symptoms and crack/cocaine, heroin, and alcohol dependence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.08.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Blazer DG. Subtypes of nonmedical opioid users: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(1–2):69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Blazer DG. How do prescription opioid users differ from users of heroin or other drugs in psychopathology: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2011;5(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181e0364e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]