Abstract

Research on distributive justice indicates that preschool-age children take issues of equity and merit into account when distributing desirable items, but that they often prefer to see desirable items allocated equally in third-party tasks. By contrast, less is known about the development of retributive justice. In a study with 4–10-year-old children (n = 123) and adults (n = 93), we directly compared the development of reasoning about distributive and retributive justice. We measured the amount of rewards or punishments that participants allocated to recipients who differed in the amount of good or bad things they had done. We also measured judgements about collective rewards and punishments. We found that the developmental trajectory of thinking about retributive justice parallels that of distributive justice. The 4–5-year-olds were the most likely to prefer equal distributions of both rewarding and aversive consequences; older children and adults preferred deservingness-based allocations. The 4–5-year-olds were also most likely to judge collective rewards and punishments as fair; this tendency declined with increasing age. Our results also highlight the extent to which the notion of desert influences thinking about distributive and retributive justice; desert was considered equally when participants allocated reward and punishments, but in judgments about collective discipline, participants focused more on desert in cases of punishment compared to reward. We discuss our results in relation to theories about preferences for equality vs. equity, theories about how desert is differentially weighed across distributive and retributive justice, and in relation to the literature on moral development and fairness.

Keywords: fairness, children, distributive justice, retributive justice, punishment

The pursuit of social justice ideally ensures that people receive their fair share of benefits, and that those who commit offenses receive a fair degree of punishment. These two forms of justice are referred to as distributive justice and retributive justice, respectively (Carlsmith & Darley, 2008; Deutsch, 2006; Piaget, 1932/1965; Rawls, 1971). Philosophical debates center on the question of whether both should operate under similar or different normative principles. On the one hand are approaches that emphasize an asymmetry, arguing that they should be regarded as fundamentally different practices, governed by different moral principles (Smilansky, 2006). According to the asymmetry account, retributive justice is aimed at rectifying injustice by using blame and punishment to reprimand and correct those who have done wrong and are deserving of punishment as a consequence. The notion of just deserts is thus the main principle. Also in line with the asymmetry account, and in contrast to retributive justice, distributive justice is seen as focused on the proper allocation of goods and services in order to regulate economic activity and foster prosperity. Here, equality and merit, rather than just deserts, are the guiding principles. The symmetry account, on the other hand, acknowledges dissimilarities in specific content, but argues that both are part of the same practice, the practice of achieving justice (Moriarty, 2003). By this account, the notion of just deserts has a place not only in retributive, but also distributive justice, as people should not only receive the punishment they deserve, but also the benefits they deserve.

This normative debate about the principles on which a theory of justice should be built raises questions about the principles we use when reasoning about case of distributive and retributive justice. What is our folk morality about justice? Is it more in accord with the asymmetry or the symmetry account? In the present research we ask if, over the course of development, children conceptualize distributive and retributive justice as similar or different with regard to the principle of desert. This is the first parallel exploration of children’s thinking about the role of desert across these two forms of justice, and the findings can shed light on whether the asymmetry in formal thought about desert in distributive and retributive justice has a basis in the way that justice is conceptualized over the course of development.

Background

Developmental studies of distributive justice

Piaget (1932/1965) discussed the distinction between a preference for equality (everyone gets the same amount) versus a preference for equity (each party gets what he or she needs or deserves). Piaget found that equality preferences did not give way to equity preferences until age 9 or later. Such findings received support in the decades that followed (e.g., Damon, 1975; Hook & Cook, 1979; Peterson, Peterson, & McDonald, 1975; Sigelman & Waitzman, 1991). However, as has been noted (e.g., Baumard, Mascaro, & Chevallier, 2012), many early studies on this topic employed complex scenarios and required children to work with large numbers (e.g., Damon, 1975; Enright et al., 1984). New methodologies suggest that nuanced concepts of distributive justice emerge earlier in development. Studies of implicit cognition in infancy find sensitivity to both equality and equity; infants expect equal distributions in context-free scenarios, and expect equitable distributions in unequal-work scenarios (Blake, McAuliffe, & Warneken, 2014; Schmidt & Sommerville, 2011; Sommerville, Schmidt, & Burns, 2013; Sloane, Baillargeon, & Premack, 2012). Studies with 3–4-year-olds show that, when simple stories are used, young children demonstrate a sense of equality and equity in their explicit judgments, such as suggesting that a protagonist who did all the baking should receive a larger cookie than a slacker (Baumard et al., 2012; see also Kenward & Dahl, 2011). Thus, preschool-age children can track and use merit-related information, often prefer to create equal distributions, and increasingly prefer to create equitable distributions as they move past the preschool years.

Developmental studies of retributive justice

While hundreds of developmental studies have focused on distributive justice, far fewer have explored cognition and behavior related to retributive justice. Little is known about the principles that guide children’s thinking in this area, let alone whether children reason about the two forms of justice in a similar fashion.

One existing line of research has focused on the role of intentions and outcomes. Piaget (1932/1965) presented children with protagonists who differed in terms of their intentions and the amount of damage they caused. Piaget found that when judging who deserved to be punished, younger children focused on outcome alone; it was not until age 10 that children referred to the individual’s intentions. However, Piaget failed to make intentions and damage equally salient. When Nelson (1980) made intentions explicit, children as young as 3 made appropriate use of motive information in their moral judgments. Killen and colleagues showed 3–8-year-old children scenarios in which a protagonist unintentionally caused another person to feel upset and found that children find it less acceptable to punish someone for harm that was caused by accident (Killen, Mulvey, Richardson, Jampol, & Woodward, 2011). Similarly, at age 4 children view accidental transgressions as more deserving of punishment than attempted-but-failed transgressions but, by age 5, the pattern is dramatically reversed (Cushman, Sheketoff, Wharton, & Carey, 2013). Thus, preschool-age children are capable of weighing motive information when thinking about punishment, and this capacity improves with advances in mental state understanding.

A second line of research on children’s thinking about punishment has used a social domain theory framework (e.g., Nucci, 2001; Smetana, 2006). Smetana (1981) found that 2–4-year-olds rated moral transgressors to be more deserving of punishment than transgressors who had violated social convention (e.g., not putting toys away correctly). Most studies in this area have replicated these results (e.g., Hollos, Leis, & Turiel, 1986; Nucci, 2001; Tisak & Jankowski, 1996; for an exception, see Jagers, Bingham, & Hans, 1996). Thus, from an early age children are attentive to issues of harm, fairness, and justice when thinking about the role of punishment.

The studies cited above employed hypothetical scenarios; fewer studies have assessed how children actually distribute punishments. One study in this third line of research tested whether 3- and 5-year-olds would punish a puppet who had behaved selfishly toward both the participant and another puppet (Robbins & Rochat, 2011). A majority of children gave up some of their own winnings to punish other players. However, only the 5-year-olds selectively punished stingy participants; the 3-year-olds punished indiscriminately. In line with this, Kenward and Östh (in press) tested children in a third-party punishment task and found that 5-year-olds selectively distributed aversive items (disgusting-tasting candies) to real adults who had behaved antisocially. Two other recent studies, with a focus on third-party punishment, showed that by age 6 children will pay a cost to punish individuals who behave unfairly to others (Jordan, McAuliffe, & Warneken, 2014; McAuliffe, Jordan, & Warneken, 2015). Further, when there is no cost to be paid children as young as 3 years of age will behave punitively toward a character whose behavior leads to a loss of desirable items for both the self, and for a third party (Riedl, Jensen, Call, & Tomasello, 2015). In another paradigm, Kenward and Östh (2012) showed 4-year-old children scenarios in which one doll attacked another doll. The preschool-age children frequently directed their own adult doll to punish the perpetrator, showing a preference for fairly-targeted punishment. To our knowledge, only one study has explored punishment-like behavior in children younger than age 3 (Hamlin, Wynn, Bloom, & Mahajan, 2011). In this study, 19-month-old toddlers saw some puppets behave prosocially and other puppets behave antisocially. When given the forced choice of taking a treat from one of the puppets, most toddlers targeted the antisocial over the prosocial puppet.

Taken together, these results indicate that even preschool-age children attend to important aspects of transgression when weighing the appropriateness of punishment, such as the harm to the victim. Further, at the end of the preschool period children attend to the perpetrator’s motives and think that intentional harm should be punished more than accidental harm. Young children also seem quite willing to engage in punishment themselves, and between the ages of 4 and 6 children begin to consistently direct their punishing behaviors at the most deserving targets.

Implications for children’s developing justice concepts

The existing research indicates that children attend to equality and merit when distributing resources, and have a notion that intentional bad behavior should be punished. However, less is known about whether general principles of justice that govern both distributive and retributive acts, based upon a notion of just deserts, or whether children conceptualize distributive and retributive acts as distinct. Using the framework of the philosophical literature, we ask if children favor a symmetry or an asymmetry approach to the enactment of distributive and retributive justice.

In the present study, a primary goal was test two competing hypotheses about the links between children’s rewarding behavior (i.e., the allocation of desirable items) and punishing behavior (i.e., the allocation of aversive items). One hypothesis is that, when allocating aversive items, children show the same age-related shift from a preference for equality to a preference for equity that has been charted in the literature on distributive justice. This hypothesis predicts symmetry in attention to just deserts across the two types of justice, with young children paying relatively less attention to desert compared to older children and adults. Such a hypothesis is plausible given that young children talk a lot about equality and sameness when asked about how and why they should allocate desirable items (e.g., Smith et al., 2013).

The alternative hypothesis is that young children prefer to see rewards distributed in an equal fashion, but punishments distributed in an equitable fashion. This hypothesis predicts asymmetrical attention to the notion of desert across the two types of justice in early childhood. By this account, young children may prefer equality when distributing positive items in order to make everyone happy, but are more selective in their punishments by apportioning negative consequences based on desert rather than equality in order to avoid making everyone feel bad. Such a pattern of results in early childhood would be consistent with formal conceptualizations of the role of desert across the two forms of justice (Moriarty, 2003; Smilansky, 2006). Importantly, should this alternative hypothesis hold, the inclusion of an adult sample will allow us to test the extent to which the asymmetry in thinking about the role of deserts also plays a role in mature thinking about justice.

In testing the hypotheses outlined above, we utilized novel methods for examining children’s punishment decisions. In the small number of studies that do exist on children’s punishment behavior, children are typically given the chance to make binary decisions (e.g., punish or not; punish Person A or Person B). Thus, while a large and ever-growing body of studies exists on how children prefer to hand out rewarding items, very little is known about how children prefer to hand out penalties when their decisions are not constrained by dichotomous response options. The present research addressed this gap in the literature, and also allowed for a direct comparison of distributive and retributive justice orientations in development by comparing different age-groups.

We also draw attention to another issue in the existing retributive justice research: punishment type. Children have primarily been asked to engage in removal punishments or - in the terminology of operant conditioning - negative punishments. For example, in Hamlin et al., 2011, and Robbins & Rochat, 2011, children punished others by removing desired stimuli, as opposed to presenting aversive stimuli. This difference between existing studies of distributive and retributive justice makes the comparison of children’s approaches to rewarding and punishing difficult. Therefore, one goal of the present research was to examine the extent to which children use similar or different approaches to allocating both punishments and rewards.

A final aspect of the present research that makes it unique was our exploration of children’s thinking about collective discipline. Collective punishment – the punishment of a whole group for the actions of a small number of its members -- has been documented in war (e.g., Darcy, 2003; Gerwarth, 2011), sports (e.g., Cushman, Durwin, & Lively, 2012) and education (e.g., Selman & Dray, 2006). Exploring children’s thinking about the fairness of collective discipline allowed us to test how strongly children adhere to an equality norm, and when in development such an adherence might soften. After all, collective punishments and rewards serve as extreme examples of equality-based distributions. Middle school students view the use of collective consequences as less acceptable than targeted discipline (Elliott, Witt, Galvin, & Moe, 1986). However, little is known about how younger children view this practice, or how collective rewards are viewed.

The exploration of collective discipline also allows for further examination of the theoretical issue regarding the extent to which there is symmetry in how desert is considered across distributive and retributive justice (Moriarty, 2003; Smilansky, 2006). If there is indeed an asymmetry, we would expect collective punishment to be rated more negatively than collective rewards, since attention to desert would be more critical in cases where aversive or harmful action is being taken. Conversely, if desert is an equally important notion across both forms of justice, we would expect to see both collective punishment and collective rewards viewed in a similar light. We also note that development may play a role. Given the hypothesis of a developmental change from strict equality to merit-based reasoning, it is reasonable to expect that the 4–5-year-olds would be more likely than the older participants to judge collective rewards as fair, and targeted (or equitable) rewards as unfair. We predicted that older children and adults would view collective punishment as unfair, given their attention to desert or merit when allocating rewarding items. We were interested in whether 4–5-year-olds would be more likely than the older groups to view collective punishments as fair, given their preferences for equality in distributive justice tasks. If such a pattern emerged, it would indicate that the notion of desert plays an increasingly important role, over the course of development, in how people think about both retributive and distributive justice.

The Present Study

Allocations of rewards and punishments

In the Allocation Phase of our study, children (aged 4–10) and adults were asked to distribute desirable classroom jobs to pairs of students (e.g., feeding four classroom pets). There were always four jobs to be distributed among two potential recipients, allowing participants to create equal or equitable distributions with ease. We predicted that the youngest children would be the most likely to show a preference for splitting the jobs equally among each pair of students, even when merit-related cues were clear. We anticipated a growing preference for equity with increasing age.

As noted above, existing developmental studies on retributive justice have generally presented children with binary choices about whether or not to punish, or about who to punish. In the Allocation Phase of the present study, participants were always asked to distribute four items to two potential recipients, meaning that children’s distributions of aversive items could be measured in a more continuous manner. This design allowed us to compare children’s relatively unconstrained preferences for distributing both rewards and punishments, and to test the two competing hypotheses we outlined above. We predicted that the youngest children would show the least sensitivity to the notion of desert, and that issues of deservingness across both forms of justice would take on greater importance with increasing age.

Collective rewards and punishments

In a final phase of the procedure, participants were asked to make fairness judgments about four scenarios in which a teacher meted out rewards and punishments. In two scenarios, the teacher punished or rewarded one student who had done a bad or good thing, respectively, but did not punish or reward others (targeted punishment/reward). In another two scenarios, the teacher punished or rewarded all students for the behavior of only one student (collective punishment/reward). This part of the procedure allowed us to assess the extent to which preschool children in particular endorse equal distributions in the relatively extreme cases of collective discipline, and when this preference changes during development. As with the Allocation Phase, in the Judgment Phase of the study we expected that the preschoolers in the study would be less likely than older children and adults to focus on issues of desert, and more likely than older participants to view collective discipline practices as fair.

Assessing developmental trends

Previous research indicates that preschool-age children are most likely to show equality preferences in third-party allocation tasks, whereas older children (age 8 and onward) are much more likely to make equitable allocations when appropriate. Thus, the inclusion of a 4–5-year-old group and an 8–12-year-old group allowed us to test developmental differences between these two key age groups. The 6–7-year-old group served as an intermediate age group that allowed us to test for more nuanced developmental trends, and the adult sample was included in order to obtain a snapshot of more mature responses to our tasks. The adult sample also allowed us to describe the extent to which, after childhood, the notion of desert is considered across distributive and retributive justice, and whether – in adult thinking – there is symmetry or asymmetry in the consideration of desert across the two forms of justice.

Method

Participants

Participating children (n = 123) included: (1) n = 50 4–5-year-olds (23 girls, Mage = 5.17, SD = .53), (2) n = 43 6–7-year-olds (23 girls, Mage = 6.91, SD = .59), and (3) n = 30 8–10-year-olds (16 girls, Mage = 9.38, SD = .87). The adult sample (n = 93) was larger than the child samples due to the tremendous ease involved in getting adults to participate via MTurk. The adult sample had a mean age of 33.57 years (SD = 11.45, range: 18 – 67).

Children participated at two museum-based lab sites (Boston Museum of Science; Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum). A wide range of ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds was represented in the sample, but most participants were White and from middle-class families. Nine additional children started the study but did not finish due to losing interest or distraction (n = 4), not answering interview questions (n = 4), and shyness (n = 1).

Adults were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and had to meet the following criteria: a US-based IP address, participation in at least 100 other MTurk tasks, and an approval rate of at least 97% given by the administrators of the previous MTurk tasks. Out of 102 adults who participated, 7 were omitted because they did not take the study seriously (e.g., one adult flippantly wrote that a child character should be beaten) and 2 because they gave confused responses on multiple trials (e.g., writing that Student A deserved more rewards after allocating more rewards to Student B).

Materials and procedures

Each child was interviewed individually and adult participants were directed from MTurk to a web-based Qualtrics survey. After a short introduction phase, there were two main test phases: first the Allocation Phase and then the Judgment Phase. In each of the six allocation trials, participants handed out desirable or aversive jobs to two students in a fictional classroom. In each of the four judgment trials, participants judged as fair or unfair a teacher’s decisions about rewarding and punishing students in the same classroom. The phases are described below.

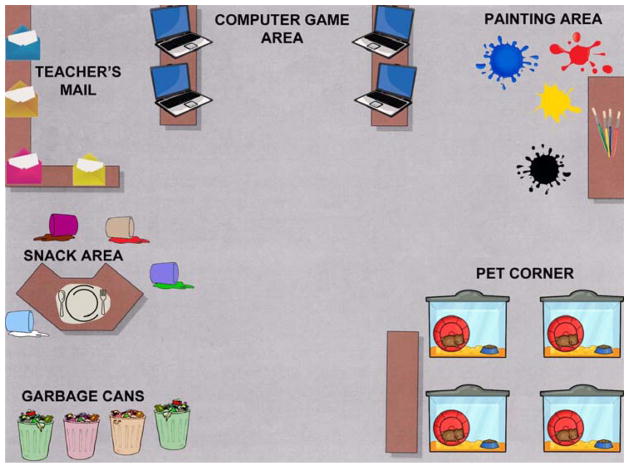

Introduction phase

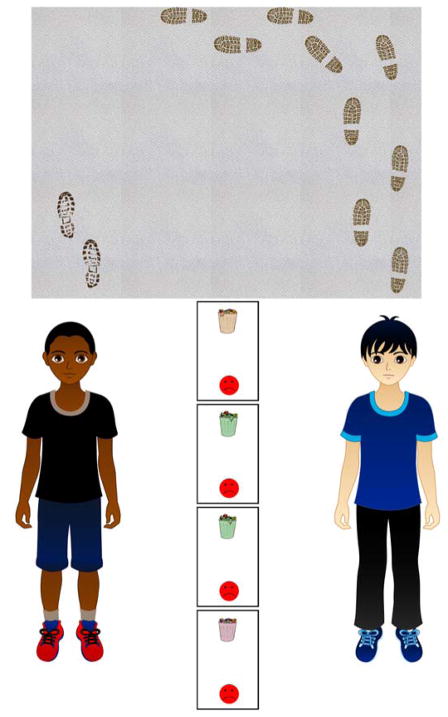

Participants viewed a fictional classroom in which there were “fun jobs” and “yucky jobs;” each was illustrated (see Appendix for examples of stimuli) and named verbally for children (or labeled for adults). The rewarding jobs were: feeding four classroom hamsters, testing four new computer games, and delivering four pieces of mail. The aversive jobs were: cleaning up four paint spills, emptying four garbage cans, and cleaning up four juice spills. Participants were told that they would decide the best way to hand out the fun and yucky jobs.

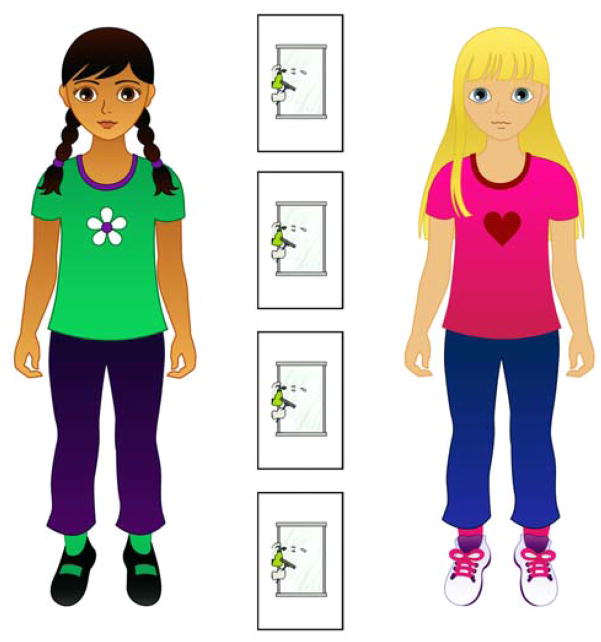

Participants then practiced allocating jobs. For children, two cards depicting fictional students were chosen at random from a stack of 14 laminated cards. The stack was always shuffled for each new participant, and it contained drawings of 7 female students and 7 male students, with a mix of ethnicities represented. The two student cards were placed in front of child participants (see Appendix for example). Four job cards were then placed between the two student cards in a vertical orientation. Children were then told:

First we’re going to practice how we give out the jobs. There are four windows in the classroom, and each one needs to be washed. Look, I can give this child one window to wash, and this other child three windows to wash. Is that one way we can do it?

Most children responded affirmatively. Some children spontaneously stated that a 3-1 split of the window washing job was unfair. In these cases, the experimenter asked if this was simply a way the jobs could be handed out, and all children answered affirmatively. Children were asked to show another way that the jobs could be allocated. Children were cued to move the job cards, and to place them on the student cards to create another allocation. Most children created a 2-2 split of the jobs. The experimenter affirmed that this was another way the jobs could be handed out. Children were then asked to show one more way the jobs could be allocated; for children who did not arrive at the solution on their own, the experimenter showed how a 4-0 allocation was also possible.

Thus, children practiced the non-verbal allocation of the job cards, and also saw that 0–4, 1–3, and 2-2 allocations were all possibilities. Adults practiced making allocations online using cursor-controlled sliders. At the end of the introduction phase, it was stated that the next part of the study would involve handing out more jobs, and that there were no right or wrong answers.

Allocation Phase

Next, children were guided through six allocation trials. The trial types are summarized in Table 1, and are further detailed in the Supplementary Online Material. For each trial, two new student cards were selected from the pre-shuffled deck so that their assignment to each trial was randomized. The scenarios in each trial were paired with rewarding and aversive jobs as described in Table 1, resulting in six trial types.

Table 1.

Summary of six trial types in Allocation Phase of study

| Students’ Contribution | Focal Behavior | Jobs to be Allocated |

|---|---|---|

| Equal | Good | Rewarding |

| Equal | Bad | Aversive |

| Unequal | Good | Rewarding |

| Unequal | Good | Aversive |

| Unequal | Bad | Rewarding |

| Unequal | Bad | Aversive |

For each trial in the Allocation Phase, children heard four key pieces of information: (1) the teacher’s request (e.g., keep the desks clean), (2) the students’ behavior (e.g., one student draws more on desks than other student), (3) the job to be allocated (e.g., cleaning up spilled paint), and (4) whether the students viewed the job as desirable or aversive. Adults read the scenarios while viewing identical stimuli. Scripts are provided in the Supplementary Online Material.

Two pictures illustrated each scenario; the first was used to frame the teacher’s request, the second showed the two students’ behaviors. For example, in the block-cleaning scenario, the first picture showed blocks on the floor and the second picture showed two containers of blocks, one much fuller than the other. For child participants, the student cards were lined up under the second picture so that participants could easily remember the students’ behaviors as they allocated the jobs. For trials in which unequal behavior was depicted, the side of the greater good or bad behavior was counterbalanced across subjects. The same arrangement was employed for adults in the online study. A depiction of how the setup looked before participants allocated jobs is provided in the Appendix. (Note that the cards for the aversive jobs had frown faces and the cards for the desirable jobs had smiley faces to reinforce the idea that some jobs were desirable and others were aversive.)

After each scenario was displayed, children received memory questions to ensure they had tracked the students’ behaviors. If a child made an error, the scenario was presented again and the memory questions were asked once more. Adults were not given memory checks, but they were able to view the stimuli on the screen as they made their allocations.

For trials with rewarding jobs, child participants were cued to distribute the jobs using the following prompt (pet feeding is used as an example here): “Now, the teacher is going to give out four fun jobs. Here they are, each job is feeding one of the four hamsters in the classroom. Both of these two kids say, ‘Yay, I love feeding the hamsters!’ What do you think is the best way to give out these four fun jobs? Can you show me?”

For trials with aversive jobs, child participants were cued to distribute the jobs using the following prompt (a cleaning job is used as an example here): “Now the teacher is going to give out four yucky jobs. Here they are, each job is cleaning up one spilled cup of juice on the floor. Both of these two kids say, ‘Yuck, I don’t like cleaning up juice spills!’ What do you think is the best way to give out these four yucky jobs? Can you show me?”

Children made allocations by moving the job cards. Adults used sliders to allocate the jobs in Qualtrics. Note that language implying that the jobs should be split between the students was avoided, consistent with the introduction phase in which a 4-0 allocation was demonstrated as a possibility. Also note that participants were not asked what the teacher would or should do, but what they themselves thought was best. After each allocation, participants were asked why they had chosen that specific allocation. Children responded verbally; answers were recorded verbatim via paper and pencil. Adults typed their justifications into a text entry box online.

For child participants, two new student cards were pulled from the deck for the next trial. Thus, a child saw two new students who were the targets of the teacher’s request in each trial. Adults were randomly assigned to see various combinations of students across the six trials.

For children, trial order was varied using a Latin square design. For adults, trial order was randomized in Qualtrics. Thus, some participants allocated aversive jobs first, while other participants allocated rewarding jobs first. Likewise, some participants took part in an Equal Behavior trial first, while others encountered Unequal Behavior trials first.

Judgment Phase

There were four trials in the Judgment Phase wherein participants heard about the teacher’s allocations of rewards and punishments. First, all of the student cards in the child version of the study were spread out on the table in no particular order. Adults in the online version of the study saw the student pictures in an array on the screen. The experimenter (or the online prompt) then stated: “Now, here are all the kids in the class.”

For child participants, the experimenter then picked up one of the student cards at random and started the first trial. The four trial types were as follows:

Targeted Punishment: One student misbehaved; only that student punished by teacher

Targeted Reward: One student did good thing; only that student rewarded by teacher

Collective Punishment: One student misbehaved; that student and all others punished

Collective Reward: One student did good thing; that student and all others rewarded

As an example, in a Targeted Punishment trial the experimenter held up one student card and said: “This kid was making lots of noise during quiet reading time. As a punishment, the teacher says that this kid has to stay inside for recess, but the rest of the kids can go outside. Is that fair? Why/Why not?” Scripts are provided in the Supplementary Online Material.

Children responded with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question about fairness, and then justified that response. Adults checked a box corresponding to their yes/no answer about fairness, and then typed justifications into a text entry box.

Scoring - Allocation Phase

The Equal Good and Equal Bad behavior trials in the Allocation Phase were scored in a binary fashion: 1 = equal split of jobs, 0 = unequal split of jobs.

The four Unequal Behavior trials in the Allocation Phase were always scored with reference to the student who engaged in more of the focal behavior. As an example: in the Unequal Bad with Aversive Jobs trial, if a participant gave the student who tracked more mud on the floor 3 aversive jobs and the other student 1 aversive job, the score for that trial would be a 3.

Justifications were coded as follows (codes were mutually exclusive):

Explicit Sameness: Explicit reference to wanting things to be the same. Examples: “Because then they’ll have the same thing” “It would be fair to give both two”

Implicit Sameness: Implicit reference to wanting things to be the same. Examples: The participant split the jobs 2-2, and said “It’s fair” or “This way is better”

Explicit Deservingness: Explicit reference to deservingness. Examples: “He made more of a mess” “She picked up more blocks” “That one kid barely did any work”

Implicit Deservingness: Implicit reference to deservingness. Example: The participant split the jobs 3-1 or 4-0, and said “It’s fair to do it this way”

Other: Responses that were uncodable using the above system. These responses included statements like “I don’t know,” and comments that were difficult to categorize such as a child’s focus on the color of the garbage cans during a trial in which the aversive job was taking out the trash.

Two research assistants independently coded all of the justifications; agreement across the four Unequal Behavior allocation trials was in the acceptable range (Kappas ranged from .75 to .81). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Scoring - Judgment Phase

Responses to the four fairness questions were scored as: 1 = fair, 0 = not fair and justifications were coded as follows (codes were mutually exclusive):

Sameness: Reference to sameness or equality when making a judgment of fair (e.g., “Everyone is treated the same”) or unfair (e.g., “Everyone should be the same”).

Deservingness: Reference to deservingness when making a judgment of fair (e.g., “He helped so he should get more”) or unfair (e.g., “Only one of the kids helped - other people shouldn’t be rewarded for something they didn’t do”).

Lesson: Statement that the discipline practice would teach a lesson (e.g., “It will encourage the other kids to do good things in the future”).

Emotion: Reference to students’ upset feelings or isolation (e.g., “She gets more and the other kids get less so the other kids will be sad”).

Other: Responses that were uncodable using the above system. These responses included statements like “I don’t know,” and comments that were difficult to categorize for the purposes of analysis, like “Obviously this kid needs some time outside to be physical. Keeping him inside will only make things worse!”

Two research assistants independently coded all of the justifications and agreement was good, kappa = .80. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Results

Preliminary analyses

We found no effects of participant gender or specific scenario/job combinations within allocation trial types. Further, there were no effects of trial order for children (order was randomized for adults). Data were pooled across these factors. Memory errors were quite rare for children (across the six allocation trials, the range of memory failure rates was 0.8% – 6.5%). All children who missed the first memory question on a particular trial subsequently answered the question correctly after the scenario was reviewed.

Allocation Phase - Equal Behavior trials

The two Equal Behavior allocation trials were used to ensure that participants did not fall into a response set, and to confirm that participants of all ages were inclined to create equal distributions when students’ behaviors were depicted as equally good or bad. In the Equal Bad with Aversive Jobs trial, the jobs were distributed with a 2-2 split the vast majority of the time: 88% for 4–5-year-olds, 95% for 6–7-year-olds, 93% for 8–10-year-olds, and 100% for adults. In the Equal Good with Rewarding Jobs trial, the jobs were again distributed with a even split most of the time: 92% for 4–5-year-olds, 91% for 6–7-year-olds, 100% for 8–10-year-olds, and 100% for adults.

Allocation Phase - Unequal Behavior trials

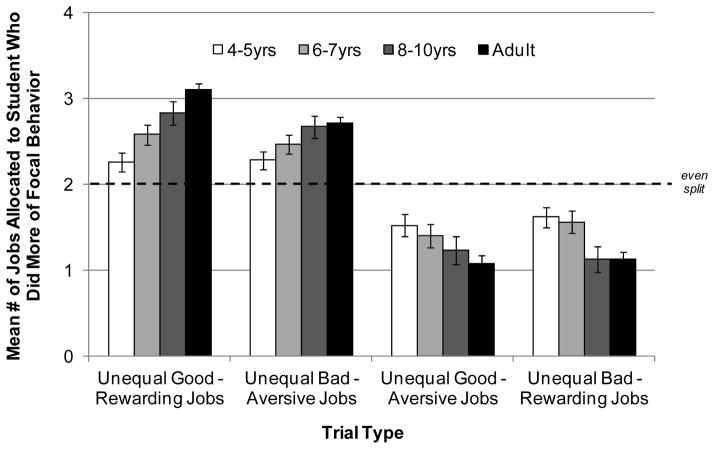

The score for each Unequal Behavior trial was computed as the number of jobs allocated to the student who engaged in more of the focal behavior. The four Unequal Behavior trials were analyzed with a 4 (trial type) × 4 (age group) mixed-measures ANOVA. There was a main effect of trial type, F(3, 636) = 141.27, p < .001, no main effect of age group, F(3, 212) = 1.19, p = .31, and an interaction of trial type and age group, F(9, 636) = 7.99, p < .001. Mean allocations are displayed in Figure 1, and histograms for each trial type are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Mean allocations of rewarding and aversive jobs as a function of trial type and age.

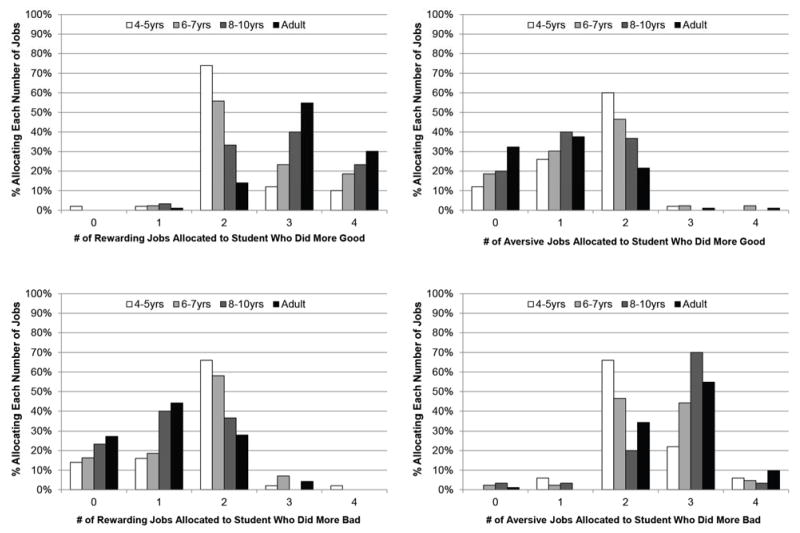

Figure 2.

Frequencies of participants’ allocations in the four Unequal Behavior allocation trials as a function of trial type and age.

As seen in Figure 1, across the four Unequal Behavior trials, the youngest children were closest to creating equal splits of the rewarding and aversive jobs. This tendency shifted in rather linear fashion toward a preference for equity-based distributions with increasing age. Analyses of simple effects were used to clarify the significant interaction.

In the Unequal Good with Rewarding Jobs trial, the 4–5-year-olds allocated significantly fewer rewarding jobs (M = 2.26) to the student who did more good, compared to the 6–7-year-olds (M = 2.58; p = .04), 8–10-year-olds (M = 2.83; p < .001), and the adults (M = 3.14; p < .001). On this trial, 6–7-year-olds also differed from the adults (p < .001). This allocation pattern corresponded to an age-related increase in Deservingness justifications, χ2(3, N = 215) = 58.30, p < .001 (see Table 2). One set of follow-up chi-square analyses indicated that all of the age groups differed in the frequency with which they used Deservingness justifications (p-values ranged from < .001 to .04). Another follow-up chi-square analysis, focusing on the subset of participants who did not create equal allocations, showed that the 4–5-year-olds (77%) were not significantly less likely to use Deservingness justifications compared to the other age groups (percentages for those groups ranged from 90% – 96%), χ2(3, N = 131) = 7.01, p = .07.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Allocation Phase justifications provided in the Unequal Behavior trials as a function of trial type and age group

| Trial type and age | Implicit Sameness | Explicit Sameness | Implicit Deservingness | Explicit Deservingness | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good w/Rewarding Jobs | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 18% | 36% | 0% | 20% | 26.% |

| 6–7yrs | 16% | 40% | 0% | 40% | 5% |

| 8–10yrs | 3% | 30% | 0% | 63% | 3% |

| Adults | 8% | 5% | 1% | 82% | 4% |

| Good w/Aversive Jobs | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 12% | 25% | 0% | 25% | 39% |

| 6–7yrs | 14% | 21% | 0% | 49% | 16% |

| 8–10yrs | 17% | 17% | 0% | 55% | 10% |

| Adults | 4% | 11% | 0% | 73% | 12% |

| Bad w/Rewarding Jobs | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 14% | 27% | 0% | 35% | 25% |

| 6–7yrs | 14% | 35% | 0% | 40% | 12% |

| 8–10yrs | 3% | 24% | 0% | 59% | 14% |

| Adults | 7% | 16% | 1% | 67% | 10% |

| Bad w/Aversive Jobs | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 10% | 24% | 0% | 32% | 34% |

| 6–7yrs | 7% | 33% | 0% | 51% | 9% |

| 8–10yrs | 3% | 17% | 0% | 77% | 3% |

| Adults | 10% | 11% | 1% | 74% | 4% |

Note. Percentages rounded to nearest whole number

In the Unequal Bad with Aversive Jobs trial, the 4–5-year-olds allocated significantly fewer aversive jobs (M = 2.28) to the student who engaged in more bad behavior, compared to the 8–10-year-olds (M = 2.67; p = .02) and the adults (M = 2.72; p < .001). The 6–7-year-olds (M = 2.47) differed from the adults (p = .05). Here again, Deservingness justifications varied as a function of age, χ2(3, N = 216) = 30.37, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds used this type of justification least often compared to the 6–7-year-olds (p = .06), the 8–10-year-olds, (p < .001), and the adults (p < .001). The 6–7-year-olds mentioned issues of deservingness less often than did the 8–10-year-olds (p = .03) and the adults (p = .005). The 8–10-year-olds and the adults did not differ, p = .88. An analysis of the subset of participants who did not create equal allocations indicated that the 4–5-year-olds (77%) were still less likely to use Deservingness justifications compared to the other age groups (range: 91% – 98%), χ2(3, N = 125) = 11.04, p = .01.

In the Unequal Good with Aversive Jobs trial, the 4–5-year-olds allocated more aversive jobs (M = 1.52) to the student who did more good, compared to the adults (M = 1.08; p = .005). The 6–7-year-olds were also different from the adults (M = 1.40; p = .05). The 8–10-year-olds were in an intermediate position (M = 1.23), and did not differ significantly from any other age group. Consistent with this allocation pattern, deservingness justifications were more common with increasing age, χ2(3, N = 214) = 31.38, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds provided significantly fewer Deservingness justifications than did all other age groups (p-values ranged from < .001 – .02). The 6–7-year-olds did not differ from the 8–10-year-olds, p = .60, but did differ from the adults, p = .006. The difference between the 8–10-year-olds and the adults was not significant, p = .07. An analysis with the subset of participants who did not create equal allocations indicated that the 4–5-year-olds (63%) were still less likely than the other age groups (range: 89% – 91%) to use Deservingness justifications, χ2(3, N = 133) = 10.34, p = .02.

Finally, in the Unequal Bad with Rewarding Jobs trial, the 4–5-year-olds allocated significantly more rewarding jobs (M = 1.62) to the student who did more bad, compared to the 8–10-year-olds (M = 1.13; p = .01) and the adults (M = 1.13; p < .001). The 6–7-year-olds (M = 1.56) also differed from the 8–10-year-olds (p = .03) and the adults (p = .005). Corresponding age differences emerged in the use of Deservingness justifications, χ2(3, N = 214) = 18.21, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds did not differ from the 6–7-year-olds (p = .63), but did use fewer Deservingness justifications compared to the 8–10-year-olds (p = .04) and the adults (p < .001). The 6–7-year-olds also used Deservingness justifications less than the adults, p = .002. When focusing only on the subset of participants who did not create equal allocations, all age groups were equally likely to use deservingness justifications (range: 89% – 94%), χ2(3, N = 121) = .89, p = .83.

Simple effects analyses of the allocation data also revealed that, within each child age group, similar numbers of jobs were allocated across the Unequal Good with Rewarding Jobs and the Unequal Bad with Aversive Jobs trials (p-values ranged from .31 to .88; all means were above 2.00). Thus, children tended to favor the student who did more good with over half of the rewarding jobs, and to target the student who did more bad with over half of the aversive jobs. Also within each child age group, similar numbers of jobs were allocated across the Unequal Good with Aversive Jobs and the Unequal Bad with Rewarding Jobs trials (p-values ranged from .30 to .60; all means were below 2.00). Children tended to allocate less than half of the rewarding jobs to the student who did more bad, and less than half of the aversive jobs to the student who did more good.

This same pattern was present within the adult group. The adults did not differ in their allocations to the student who engaged in the focal behavior across the Unequal Good with Aversive Jobs and the Unequal Bad with Rewarding Jobs trials (p = .61; both means < 2.00). However, the adult allocations across the Unequal Good with Rewarding Jobs (M = 3.14) and the Unequal Bad with Aversive Jobs (M = 2.72) trials did differ, p < .001.

In order to test one of the hypotheses raised above, that similar approaches might govern the allocation of rewarding and aversive stimuli, we computed correlations between the allocation trials to more fully explore the extent to which this was true for each age group (see Table 3 for complete results). For the 4–5-year-olds, allocations in the Unequal Good with Rewarding Jobs and the Unequal Bad with Aversive Jobs trials were significantly correlated, but none of the other correlations reached significance. For the 6–7-year-olds, three of the six correlations reached significance, and for the 8–10-year-olds more than half (four) of the correlations were significant. In the adult group, all six of the correlations reached significance (aided, in part, by the large adult sample). Thus, some consistency across trials in which rewarding and aversive stimuli were allocated was present by age 6, and thereafter such inter-trial consistency was increasingly common.

Table 3.

Inter-trial correlations for participants’ allocations in the four Unequal Behavior trials by age group

| 4–5yrs | 6–7yrs | 8–10yrs | Adults | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good w/Rewarding Jobs and Good w/Aversive Jobs | −.25† | −.44** | −.45** | −.34*** |

| Good w/Rewarding Jobs and Bad w/Rewarding Jobs | −.17 | −.74*** | −.66*** | −.24* |

| Good w/Rewarding Jobs and Bad w/Aversive Jobs | .14 | .17 | .35† | .29** |

| Good w/Aversive Jobs and Bad w/Rewarding Jobs | .50*** | .17 | .28 | .25* |

| Good w/Aversive Jobs and Bad w/Aversive Jobs | −.22 | −.68*** | −.43** | −.25* |

| Bad w/Rewarding Jobs and Bad w/Aversive Jobs | −.25† | −.16 | −.45** | −.34*** |

Note.

p < .09

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

A final analysis compared the 4–5-year-olds’ allocations to the equal-split mark of 2.00. Although the 4–5-year-olds were consistently closer to equal-split allocations than were the older groups, they nonetheless differed significantly from an equal split across all Unequal Behavior trials (p-values ranged from .02 to < .001).

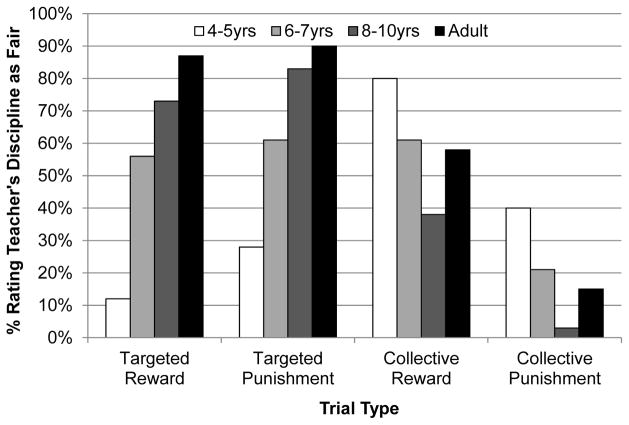

Judgment Phase

The frequencies of participants who rated the teacher’s discipline practices as fair in judgment trials are presented in Figure 3. In the Targeted Reward scenario, one student behaved helpfully and the teacher rewarded only that student. Figure 3 displays the age-related increase in the endorsement of the teacher’s response; this was significant, χ2(3, N = 216) = 79.90, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds were significantly more likely than all other groups to rate the targeted reward as unfair (all p-values < .001). The 6–7-year-olds did not differ from the 8–10-year-olds (p = .13), but did differ from the adults, p < .001. The 8–10-year-olds and the adults did not differ, p = .08. Correspondingly, the use of Deservingness justifications varied as a function of age, χ2(3, N = 215) = 53.57, p < .001 (see Table 4). The 4–5-year-olds used Deservingness justifications less often than did all other age groups, all p-values < .001. The 6–7-year-olds did not differ from the 8–10-year-olds (p = .11), but did mention deservingness less often than did the adults (p = .03). The 8–10-year-olds and adults did not differ, p = .99.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of participants rating teacher’s discipline practices as fair in judgment trials as a function of trial type and age.

Table 4.

Frequencies of Judgment Phase justifications as a function of trial type and age group

| Justification Type

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial type and age | Sameness | Deservingness | Lesson | Emotion | Other |

| Targeted Reward | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 59% | 8% | 0% | 8% | 25% |

| 6–7yrs | 33% | 51% | 0% | 7% | 9% |

| 8–10yrs | 20% | 70% | 0% | 0% | 10% |

| Adults | 9% | 70% | 14% | 0% | 8% |

| Targeted Punishment | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 4% | 20% | 0% | 52% | 24% |

| 6–7yrs | 2% | 61% | 0% | 33% | 5% |

| 8–10yrs | 3% | 80% | 0% | 3% | 13% |

| Adults | 3% | 73% | 14% | 0% | 10% |

| Collective Reward | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 60% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 28% |

| 6–7yrs | 49% | 33% | 0% | 0% | 19% |

| 8–10yrs | 23% | 60% | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Adults | 11% | 42% | 20% | 0% | 27% |

| Collective Punishment | |||||

| 4–5yrs | 28% | 26% | 0% | 20% | 26% |

| 6–7yrs | 14% | 63% | 0% | 5% | 19% |

| 8–10yrs | 0% | 94% | 0% | 3% | 3% |

| Adults | 1% | 79% | 10% | 0% | 11% |

Note. Percentages rounded to nearest whole number

In the Targeted Punishment scenario, one student misbehaved and the teacher punished only the misbehaving student. Figure 3 displays the age-related increase in the view that the teacher’s behavior was fair; χ2(3, N = 215) = 62.91, p < .001. Follow-up analyses revealed that there were significant differences between every age group (p-values ranged from < .001 – .04) except between the 8–10-year-olds and the adults, p = .26. Age differences also emerged in the use of Deservingness justifications, χ2(3, N = 216) = 44.69, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds were less likely than all other age groups to mention deservingness, all p-values < .001. The three other age groups did not differ, p-values ranged from .08 – .45.

In the Collective Reward scenario, one helpful student and all others were rewarded by the teacher. As displayed in Figure 3, we found that (1) the teacher’s practice was viewed as increasingly unfair as child age increased, and (2) that adults viewed the teacher’s collective reward decision as fairer than did the 8–10-year-olds; χ2(3, N = 215) = 14.41, p = .002. Follow-up tests showed that the 4–5-year-olds, most of whom viewed the collective reward as fair, were different from all other age groups (p-values ranged from < .001 – .04). The other three age groups did not differ significantly from one another (p-values ranged from .06 to .79). The use of Deservingness justifications varied as a function of age, χ2(3, N = 215) = 21.73, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds were less likely than all other age groups to mention deservingness, p-values ranged from < .001 – .02. The 6–7-year-olds were less likely than the 8–10-year-olds to mention deservingness, p = .02. There were no other significant differences.

In the Collective Punishment scenario, one misbehaving student and all others were punished by the teacher. All age groups endorsed the practice of collective punishment at rates lower than 50%, but there were significant age differences, χ2(3, N = 216) = 18.88, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds were significantly more likely than all other age groups to approve of collective punishment, p-values ranged from < .001 – .05. Compared to the 8–10-year-olds, the 6–7-year-olds were more likely to judge the collective punishment as fair, p = .03. The judgments of the adults did not differ significantly from those of the 6–7-year-olds (p = .40) or the 8–10-year-olds (p = .09). There were also age differences in the use of Deservingness justifications, χ2(3, N = 216) = 51.74, p < .001. The 4–5-year-olds were less likely to mention deservingness compared to all other age groups, all p-values < .001. The 6–7-year-olds used this justification type less often than did the 8–10-year-olds (p = .003) and the adults (p = .05). The difference between the 8–10-year-olds and the adults was not significant (p = .06).

A number of focused McNemar tests were used to examine how participants within each age group differed in their judgments across some of the four scenarios in which the teacher handed out rewards and punishments. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of within-age-group comparisons of fairness judgments

| Age | Tar Pun : Tar Rew | Col Rew : Col Pun | Col Rew : Tar Rew | Col Pun : Tar Pun |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–5 | >** | >*** | >*** | = |

| 6–7 | = | >*** | = | <** |

| 8–10 | = | >** | <* | <*** |

| Adults | = | >*** | <*** | <*** |

Note. > denotes more fair, < denotes less fair, = denotes equally fair.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

A final, exploratory analysis probed the adults’ justifications in the Collective Punishment and Collective Reward trials. Although the majority of adults viewed these practices as unfair, Fisher’s exact tests showed that adults were more likely than children to view collective rewards and punishments as useful for teaching lessons about proper behavior (both p-values < .001).

Associations between Allocations and Judgements

Lastly, we explored connections between responses in the Allocation and Judgment Phases. As noted above, the collective consequence trials in the Judgment Phase of the study represent extreme examples of equality-based allocations of rewards and punishments. We thus predicted that participants who were more likely to create equal distributions in the Allocation Phase would be more likely to judge collective consequences as acceptable in the Judgment Phase.

We first created summary measures for each phase. For each of the four Unequal Behavior allocation trials, participants were given one point for each Deservingness justification they provided, creating a 0 – 4 scale. Means on this measure were: 1.12 for the 4–5-year-olds (SD = 1.41); 1.79 for the 6–7-year-olds (SD = 1.51); 2.50 for the 8–10-year-olds (SD = 1.55); and 2.98 for the adults (SD = 1.26). For each of the two targeted-consequences judgment trials, participants received one point if they provided a ‘fair’ judgment, and for each of the two collective-consequences judgment trials, participants given one point if they provided an ‘unfair’ judgment. This also resulted in a scale ranging from 0 to 4. Means on this measure were: 1.20 for the 4–5-year-olds (SD = 1.09); 2.35 for the 6–7-year-olds (SD = 1.38); 3.21 for the 8–10-year-olds (SD = 1.13); and 3.04 for the adults (SD = .86). The two scales were subjected to a partial correlation analysis, controlling for age (measured in years), and were significantly associated, partial r = .44, p < .001. As a follow-up to this analysis, we created a 4-point scale for the Allocation Phase in which a point was given for each scenario in which a participant did not create an equal allocation on an Unequal Behavior trial. Means on this measure were: 1.34 for the 4–5-year-olds (SD = 1.48); 1.93 for the 6–7-year-olds (SD = 1.58); 2.73 for the 8–10-year-olds (SD = 1.41); and 3.02 for the adults (SD = 1.26). Controlling for age, this scale was also correlated with the Judgment Phase summary scale, partial r = .41, p < .001. Thus, controlling for age, participants who were more likely to focus on equity and deservingness in the Allocation Phase were also more likely to view targeted consequences as fair and collective consequences as unfair in the Judgment Phase.

Discussion

Does the development of thinking about fair punishment mirror the development of thinking about distributive justice, or are there systematic differences in children’s thinking about these two types of justice during development? Further, does the notion of desert figure more prominently in thinking about retributive justice compared to distributive justice, mirroring formal theoretical treatments of these forms of justice, or is the importance of desert viewed similarly in both contexts? Our study is the first to explore these questions by directly comparing children’s retributive and distributive justice orientations. Further, the present study joins a small number of studies involving observations of children’s actual punishment allocations. In those extant studies, children are commonly faced with the dichotomous choices of administering punishment or not, or punishing one person versus another. Thus, little information exists about how children choose to distribute demerits when their decisions are freed from the constraints of binary response options. The findings summarized below begin to fill this gap in the literature.

Four-through-ten-year-old children and a group of adults allocated rewarding and aversive jobs to pairs of students in a fictional classroom, and made fairness judgments about the allocations of rewards and punishments made by the classroom teacher. Children and adults showed a strong preference for creating equal allocations of rewarding and aversive jobs when the behavior of the two students was the same. However, when one student did more of a good or bad thing than another student, the youngest children were the most likely to create relatively equal allocations of both rewarding and aversive jobs. With increasing age, a preference for equitable distributions of rewarding and aversive jobs emerged in the Unequal Behavior trials. Below, we highlight a number of notable aspects of these findings.

We first underscore the finding most central to the hypotheses outlined in the introduction: we found an unmistakable symmetry in the way that participants in each age group approached the allocation of rewarding and aversive consequences (Figure 1). The 4–5-year-old children were more likely to create relatively equal distributions of both rewarding and aversive jobs. In a mirror image of what they did with the rewarding tasks, the older children and adults tended to give more than half of the aversive tasks to characters who behaved relatively badly, and less than half of the aversive tasks to characters who behaved positively. These results show for the first time that, across development, similar decisions are made about how to engage in distributive and retributive justice, and that this overarching fairness orientation shifts from equality- to equity-favoring with increasing age. Thus, thinking about retributive justice by older children and adults is characterized by attention to the notion of desert, consistent with normative theories of justice. Interestingly, developmentally mature thinking about distributive justice involves a similar attention to desert, in line with the symmetry account from the philosophical literature (Moriarty, 2003).

Another novel feature of the present research was the exploration of children’s judgments regarding targeted and collective consequences. Participants were faced with a teacher’s use of equity-based consequences (targeted punishments and rewards) and equality-based consequences (collective punishments and rewards). The inclusion of a task involving collective consequences allowed us to test whether young children, who often prefer equal distributions of rewards in third-party tasks, would continue to show this preference in more extreme equal-allocation situations, such as when everyone receives punishment for the misdeeds of a single group member. As predicted, the 4–5-year-olds were the most likely to endorse the use of both collective rewards (80%) and punishments (40%) as fair, and were least likely to view targeted rewards (12%) and punishments (28%) as fair. These views were less common in older children and adults.

The investigation into views on collective discipline also provided a second look at the question of whether the role of desert is weighted differently across acts of retributive and distributive justice. Although no such difference was found across the two types of justice in the Allocation Phase of the study, a clear difference emerged in the Judgment Phase. Collective rewards were viewed by all age groups as significantly more acceptable than collective punishments. Thus, starting in the elementary school years, when individuals have relatively nuanced control over allocations of rewards and punishments, the preference is to attend to issues of desert in both cases. However, the pattern of results also indicates that the notion of desert may play more of a role when people are asked to judge the acceptability of collective retribution, in contrast to the acceptability of collective reward. Perhaps because acts of punishment inherently involve causing harm to others children thought that causing a whole group of people to experience punishment following the transgression of an individual (collective punishment) was viewed as unfair by most participants. However, because acts of reward do not inherently carry harmful consequences, causing large numbers of people to experience favorable consequences following the positive behavior of an individual (collective reward) was viewed as acceptable by most participants. These results from the Judgement Phase of the study provide some support for the notion that there is an asymmetry in the weight placed on desert in matters of justice, with more weight given to desert in the context of retributive justice, compared to distributive justice.

We also examined associations between participants’ allocations and judgments; controlling for age, we found a robust continuity across behavior and judgment. Participants who were more likely to justify their own allocations with references to equality concerns were also more likely to judge the teacher’s use of collective consequences as fair in the judgment task. An important implication of this association is that even young children display an explicit awareness of the principles that guide their behavior where distributive and retributive justice are concerned; they are able to articulate their stance rather than simply behaving reflexively. These findings also indicate that, for a substantial percentage of young children, the preference for equal distributions found in distributive justice tasks (e.g., Baumard et al., 2012) is quite strong; strong enough that whole group punishment is viewed as fairer than equitable punishment.

An intriguing finding that emerged from our analyses of collective consequences was that 58% of adults viewed collective rewards as fair, and 15% viewed collective punishment as fair (compared to 38% and 3% of the 8–10-year-olds, respectively). Many of the adults who endorsed collective consequences viewed these discipline techniques as ways to teach lessons to a larger group. The current findings suggest that such an approach by adult authority figures may be better received by younger, rather than older children, especially where collective rewards are concerned. However, this is untested and is a ripe area for future research. In addition to exploring reactions to actual targeted and collective consequences, a number of other questions related to this topic are unexplored. How are collective punishment and rewards used with children? Are such approaches effective, or do they have unintended consequences (e.g., undermining child-adult relationships)? Do collective consequences lead to self-policing among children?

Directions for Future Research

Here we turn to other open questions that warrant exploration, and we also touch on some limitations of the present research. One open question concerns the extent to which a shared process governs how people allocate both merits and demerits. The justification data suggest that, especially after the preschool years, the nature of this shared process may be cognitive in nature, as the focus of the responses involves a consistent and increasing focus on identifying the party most deserving of reward or punishment. For children in the preschool years, the justification data suggest that there may also be other processes at play (e.g., emotional concerns about others feeling sad) when decisions about distributive and retributive justice are made. Identifying the underlying processes involved in thinking about fair rewards and punishments -- and the extent to which such processes are common to both distributive and retributive justice -- is beyond the scope of the present study. However, this represents an important next step in this line of research.

We next touch on the question of whether many of the 4–5-year-olds in the Allocation Phase opted for a 2-2 split of the jobs - both rewarding and aversive – because such a division is cognitively less demanding. The data speak against this view. The youngest children were also the most likely to endorse as ‘fair’ the even spread of rewards and punishments by a teacher, and such an endorsement was no easier to make than the alternative response of ‘unfair.’ Further, when examining the justifications offered in the judgment task, the 4–5-year-olds frequently made mention of the negative emotional consequences (e.g., isolation, feeling sad) that a misbehaving child who is targeted with punishment might feel. It may be that many preschool-age children view the even spread of consequences as a way to maintain positive feelings, while older children prioritize issues of deservingness. Deutsch has discussed the notion that a desire to maintain positive feelings and social harmony can lead to a preference for equal allocations, while a desire to ensure productivity may lead to a preference for equitable allocations (Deutsch, 1975; Tyler & Belliveau, 1995). Our results fit with this account. However, more research is needed to directly test the notion that that preschool-age children’s preferences for relatively equal divisions of rewards and punishments are driven, in part, by a desire to promote or maintain social harmony.

Another important avenue for future research involves comparing across first- and third-party allocation scenarios. In the study reported above, the participants took part in third-party tasks in which the self did not stand to gain or suffer from the allocations. There is reason to expect that children’s behavior might differ if they were placed in a first-party version of our procedure, where allocations of rewards and punishments to another person leave the self with less of the good and the bad, respectively. In studies on sharing behavior, young children like to create equal distributions of items when they are not potential recipients (e.g., Baumard et al., 2012; Shaw & Olson, 2012), but when dividing up resources in first-party tasks, they tend to allocate more to themselves than a peer (Benenson, Pascoe, & Radmore, 2007; Birch & Billman, 1986; Blake & Rand, 2010; Rochat et al., 2009). Some factors boost costly sharing in early childhood, such as being led to believe that another party has worked harder (Kanngiesser & Warneken, 2012), or allocating valued items to friends (Moore, 2009; Paulus & Moore, 2014). Further, when certain cues are made available (e.g., verbal statements of need), 2.5-year-olds altruistically lend their own valued items to others (Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010). However, many studies of first-party sharing chart a gradual, age-related shift from favoring the self to behaving in line with fairness norms (Blake & McAuliffe, 2011; Smith, Blake, & Harris, 2013). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that 4–5-year-olds would be especially likely to create distributions that are favorable to the self when allocating rewarding and aversive classroom jobs in a first-party task.

We conducted an initial study to test this hypothesis, and we report on these data in the Supplementary Online Material. Children took part in the same procedure that is described above, but were asked to imagine themselves in the role of one of the classroom students in each scenario (this was facilitated via the use of a recipient card with the participant’s name on it). While a small number of differences emerged between the third- and first-party tasks, none of mean differences involved children putting the self at an advantage over others. In fact, the 4–5-year-olds consistently created equal allocations in the first-party task, which is in line with the data reported above. With the minimal differences between the two studies in mind, we acknowledge that the hypothetical first-party tasks presented in the Supplementary Online Material did not actually put children in the position of gaining or losing. Although children imagined themselves in the role of well- or poorly-behaved students, as evidenced by the fact that most participants used self-referential pronouns (e.g., I, me, us) in their justifications, the hypothetical task certainly carried less weight than actual punishment and reward situations. An important next step will involve exploring children’s allocations in situations in which the self truly stands to benefit or suffer. When adults are asked to allocate unpleasant tasks between the self and another person in studies of moral hypocrisy, their behavior is often self-favoring and at odds with endorsed fairness norms (e.g., Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2007). In a true first-party allocation task, we would expect similar trends in children.

We now turn to two issues related to study design. First, in the Allocation Phase the words ‘punishment’ and ‘reward’ were not used. Given this, it is conceivable that some children may not have viewed the allocations as rewards or punishments. While this issue can be explored in future research, there are a number of reasons that this does not present a large concern. First, in each trial participants were alerted to the fact that the recipients found the jobs either desirable or aversive, with the recipients making clear statements such as “Yuck, I don’t like taking out the trash cans!” To reinforce this notion, the experimenter referred to the aversive jobs as ‘yucky jobs.’ Given that children understand states of desires from an early age (Wellman & Liu, 2004), and 3-year-olds can appropriately connect desire satisfaction (or the lack thereof) with emotion (Yuill, 1984), it is fairly safe to assume that this part of our experimental design was within the grasp of even the youngest particpants. Second, we note that both justification patterns and actual allocations in the Allocation Phase were significantly correlated with participant’s fairness judgments in the Judgment Phase, where the words ‘punishment’ and ‘reward’ were used explicitly. This suggests that in the Allocation Phase children saw the aversive tasks as punitive in nature and the rewarding tasks as rewarding in nature. Finally, the age-related trend with regard to the allocations of rewarding jobs is congruent with previous research on developing views of distributive justice, further suggesting that the framing of the jobs - in this case the rewarding jobs - was indeed effective.

A second issue is that participants were asked to allocate desirable or aversive jobs, whereas previous studies have asked participants to distribute or take away items (e.g., treats or stickers). We used jobs for three key reasons. First, the assignment of jobs in a classroom has a high degree of ecological validity; starting in preschool children are asked to help with enjoyable and undesirable jobs in their classrooms (e.g., watering plants, feeding pets, cleaning tables, etc.). Second, it is not uncommon for adults to assign children chores as consequences for negative behavior (many experts recommend that the chore should be related to the transgression; e.g., Nelson, 1996), and such approaches seem effective in small-scale studies (e.g., Fischer & Nehs, 1978; Hohnhorst & Roberts, 1992). Third, in our exploration of retributive justice, our goal was to investigate how children viewed the use of presentation punishments (i.e., handing out aversive consequences). This approach allowed us to directly compare participants’ approaches to distributive and retributive justice. We considered the use of pleasant and aversive jobs as the best way to do this; the alternative would have been something foreign to children and potentially hard to interpret, such as asking children in the aversive item trials to distribute items like pieces of coal as punishments. To our knowledge, there is no a priori reason to expect that children’s approaches to handing out jobs versus items would be different. Nonetheless, future studies on this topic will advance our understanding of children’s thinking and behavior by using a variety of punishment and reward types, including punishments that involve the removal of something desirable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Deborah Anderson, Anna Straussberger, Angel Wang, Caitlin Heath, Jaclyn Peraino, Yardain Amron, Caitlin Authier, Elizabeth Williams, Rachel Forche, Stephanie Mezzanatto, Zoe Van Dyke, and Kathileen Tran for their help with data collection. We are grateful to the Boston Museum of Science and the Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum for serving at research sites for this study. Finally, we thank the parents and children who took part in this research. Work on this research by C.E.S was supported by Award Number T32HD007109 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development.

APPENDIX

Figure A1.

Schematic representation of fictional classroom depicting the rewarding and aversive jobs. Participants viewed this prior to Allocation Phase.

Figure A2.

Arrangement of recipients and window-washing jobs, as used in the introduction phase.

Figure A3.

Example of how recipient cards (lower left and right), job cards (lower middle), and scenario card (top) were arranged in the Allocation Phase.

Contributor Information

Craig E. Smith, Email: 999craig@gmail.com.

Felix Warneken, Email: warneken@wjh.harvard.edu.

References

- Baumard N, Mascaro O, Chevallier C. Preschoolers are able to take merit into account when distributing goods. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(2):492–498. doi: 10.1037/a0026598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benenson JF, Pascoe J, Radmore N. Children’s altruistic behavior in the dictator game. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2007;28(3):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Billman J. Preschool children’s food sharing with friends and acquaintances. Child Development. 1986;57(2):387–395. doi: 10.2307/1130594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K. “I had so much it didn’t seem fair”: Eight-year-olds reject two forms of inequity. Cognition. 2011;120(2):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K, Warneken F. The developmental origins of fairness: The knowledge–behavior gap. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014;18(11):559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, Rand DG. Currency value moderates equity preference among young children. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2010;31(3):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsmith KM, Darley JM. Psychological aspects of retributive justice. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 40. San Diego, CA US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. pp. 193–236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F, Durwin AJ, Lively C. Revenge without responsibility? Judgments about collective punishment in baseball. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012;48(5):1106–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F, Sheketoff R, Wharton S, Carey S. The development of intent-based moral judgment. Cognition. 2013;127(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. Early conceptions of positive justice as related to the development of logical operations. Child Development. 1975;46(2):301–312. doi: 10.2307/1128122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darcy S. Punitive house demolitions, the prohibition of collective punishment, and the Supreme Court of Israel. Penn State International Law Review. 2003;21(3):477–507. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. Equity, equality, and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues. 1975;31(3):137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. Justice and conflict. In: Deutsch M, Coleman PT, Marcus EC, editors. The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice. 2. Hoboken, NJ US: Wiley Publishing; 2006. pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SN, Witt JC, Galvin GA, Moe GL. Children’s involvement in intervention selection: Acceptability of interventions for misbehaving peers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1986;17(3):235–241. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.17.3.235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD, Bjerstedt A, Enright WF, Levy VM, Lapsley DK, Buss RR, Harwell M, Zindler M. Distributive justice development: Cross-cultural, contextual, and longitudinal evaluations. Child Development. 1984;55(5):1737–1751. doi: 10.2307/1129921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J, Nehs R. Use of a commonly available chore to reduce a boy’s rate of swearing. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1978;9(1):81–83. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(78)90096-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwarth R. Hitler's hangman: the life of Heydrich. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin J, Wynn K, Bloom P, Mahajan N. How infants and toddlers react to antisocial others. PNAS. 2011;108(50):19931–19936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110306108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnhorst AD, Roberts MW. Evaluation of a brief work chore discipline procedure. Behavioral Residential Treatment. 1992;7(1):55–69. doi: 10.1002/bin.2360070107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollos M, Leis PE, Turiel E. Social reasoning in Ijo children and adolescents in Nigerian communities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1986;17(3):352–374. doi: 10.1177/0022002186017003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JG, Cook TD. Equity theory and the cognitive ability of children. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(3):429–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Bingham K, Hans SL. Socialization and social judgments among inner-city African-American kindergartners. Child Development. 1996;67(1):140–150. doi: 10.2307/1131692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JJ, McAuliffe K, Warneken F. Development of in-group favoritism in children’s third-party punishment of selfishness. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(35):12710–12715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402280111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanngiesser P, Warneken F. Young children consider merit when sharing resources with others. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e43979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward B, Dahl M. Preschoolers distribute scarce resources according to the moral valence of recipients’ previous actions. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(4):1054–1064. doi: 10.1037/a0023869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward B, Östh T. Five-year-olds punish antisocial adults. Aggressive Behavior. doi: 10.1002/AB.21568. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward B, Östh T. Enactment of third-party punishment by 4-year-olds. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:373. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]