Abstract

Purpose

Significant gaps persist in our understanding of the etiological factors that shape the progression of mental health symptoms (MHS) among perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) youths. This study sought to assess the changes in MHS among PHIV+ and PHEU youths as they transition through adolescence, and to identify the associated psychosocial factors.

Methods

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study of 166 PHIV+ and 114 PHEU youths (49% male, ages 9 – 16 at baseline) in New York City. Individual interviews were administered at baseline and subsequently over a 5 year period. MHS were assessed using the youth version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV). Predictive growth curve analyses were conducted to assess longitudinal changes in MHS and identify the relevant factors. Level I predictors included: time, major life events, household poverty, caregiver mental health, and neighborhood stressors. Level II predictors included youths’ sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender, HIV status) and baseline future orientation scores.

Results

The changes in youths’ MHS followed a quadratic growth curve, and were positively associated with the number of major negative life events, and neighborhood stressors experienced. Youths’ HIV status, household poverty and caregiver mental health were not significantly associated with youths’ MHS.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that irrespective of youths’ HIV status, major life events and neighborhood stressors increase MHS among PHIV+ and PHEU youths. There is a need for interventions to reduce the impact of stressors on the mental wellbeing of PHIV+ and PHEU youths.

Keywords: Adolescents, distress, stress

Introduction

Perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) youths exhibit higher rates of mental health problems (MHPs) including psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and behavioral disorders than youths in the general population (1–3). A 2006 systematic review found higher rates of MHPs among PHIV+ youths compared to non-infected youths, including behavioral disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 28.8% vs. 8.7%), and mood disorders such as depression (25% vs. 14.3%) (3). MHPs have been associated with non-adherence to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) in PHIV+ youths and sexual risk taking among PHIV+ and PHEU youths, which increase the risk for transmitting (in PHIV+) or acquiring (in PHEU) HIV (4, 5). Thus, understanding pathways to MHPs is critical in both groups given the potential consequences.

MHPs among PHEU and PHIV+ youths have been attributed to a complex array of biogenetic and psychosocial factors including neurological deficits, low self-esteem, stigma, stressful life events (e.g. bereavement, family conflict and dissolution), caregiver HIV status, and poor caregiver mental or physical health (6–8). Neighborhood factors such as poverty, violence, victimization and racism, common among inner city neighborhoods in which HIV infection has been concentrated in the United States (US) (9), have also been associated with youth MHPs (6, 10). However, significant uncertainty remains about the role of pediatric HIV in the etiology of MHPs across the developmental continuum. In some studies, researchers have reported significantly higher rates of MHPs among PHIV+ youths compared to PHEU youths (1), while other studies have found higher rates among PHEU youths compared to PHIV+ youths (11), and still others have found no difference at all (2, 12). Little is known about how individual and contextual-level factors influence the progression of MHPs among PHIV+ and PHEU youths across adolescence, yet such information is critical to tailoring preventive and treatment interventions to the needs of this population. Moreover, studies of MHPs among PHIV+ and PHEU youths are largely cross-sectional (1, 11, 13), constrained by small sample sizes (14, 15), and focus on psychiatric disorders only (1, 13).

The sole focus on psychiatric disorders may be problematic, as youths who experience mental health symptoms (MHS) but do not meet the diagnostic criteria stipulated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) may be lumped with youths without any problem. This obscures the impact that MHS may have on youths’ and on the prediction of psychiatric disorders in later adolescence or adulthood (16). To advance our understanding of MHPs among PHIV+ and PHEU youths, this paper utilizes MHS counts rather than psychiatric diagnoses. These MHS counts are classified into two primary behavioral symptom typologies- internalizing symptoms (e.g. depressive and anxiety symptoms) and externalizing symptoms (e.g. conduct disorder, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder), to enable examination of common symptom patterns (17) and assessment of group effects (e.g. age, sex).

Explicating the changes in youths’ MHS across adolescence and associated risk factors is critical to understanding the etiology of MHPs among PHIV+ and PHEU youths, and could inform the development of evidence-based mental health services for this population (7). This paper seeks to expand the current literature on the mental health of PHIV+ and PHEU youths by utilizing data from a longitudinal study to assess prospective changes in MHS and identifying the contextually relevant factors that influence these changes as youth transition through adolescence. To inform these exploratory analyses, we used key elements of Social Action Theory (SAT) (18). Specifically, we examined the association between changes in MHS and youths’ sociodemographic characteristics, their context, and their self-regulation. Consistent with prior research, we hypothesized that PHIV+ youths would have higher rates of increase in MHS compared to PHEU youths (1); changes in youths’ MHS across adolescence would be positively associated with greater exposure to negative contextual factors (e.g., greater environmental stress, caregiver distress, and household poverty (6–8, 10) and negatively associated with self-regulation factors (e.g., future orientation) (19, 20).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This paper utilizes data from the Child and Adolescent Self-Awareness and Health Study (CASAH), a multi-center longitudinal study of PHIV+ and PHEU youths recruited from four medical centers in New York City (NYC). Participants included the youths and their primary caregiver who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) youths aged 9–16 years with perinatal exposure to HIV (as confirmed by medical providers and charts), (2) cognitive capacity to complete the interviews, (3) English or Spanish speaking, and (4) caregiver with legal ability to sign consent for child participation. To isolate the effect of HIV on mental health and behavioral health outcomes, we included a comparison group of children from similar environments who were perinatally HIV exposed, but uninfected. In the absence of a large enough pool of PHEU youths in study clinics, multiple children were recruited from the same family, providing they met eligibility criteria. Participants were recruited between 2003 and 2008. Of the 443 eligible participants, 11% refused contact with the research team, and 6% could not be contacted by the site study coordinators. A total of 367 (83%) caregiver–youth dyads were approached, of whom N = 340 were enrolled at baseline (77% of eligible families; 206 PHIV+ and 134 PHEU youth).

Data were collected using caregiver and youth interviews, conducted separately, but simultaneously whenever possible conducted at the youth’s/caregiver’s homes, their medical clinics, or our research office, by trained bachelor-level interviewers. Based on participant preference, all youths were interviewed in English and 67 caregiver interviews were conducted in Spanish. Consistent with standard procedures for translation and back-translation (23), all study instruments were translated and certified by an Institutional review board (IRB) approved expert translator. IRB approval was obtained from all study sites. All caregivers provided written informed consent for themselves and their youths who were <18 years of age; youths provided written assent (if <18 years) or consent if ≥18 years. Monetary reimbursement for each completed session ($25) and public transport was provided.

These analyses utilized three waves of data collection: CASAH-1 (baseline and follow-up: FU1) and CASAH-2 (FU2). The baseline and FU1 interviews were completed approximately 18 months apart (Myears = 1.65, SD = 0.45). CASAH-2 was not initially planned; data collection was initiated when authors secured additional funding to follow the CASAH-1 cohort. CASAH-2 involved re-recruiting families from CASAH-1. Families were eligible for CASAH-2 interviews if the youths were at least 13 years old, and it had been at least 1 year since their FU1 interview. All youth and their caregivers who were re-enrolled in the study at FU2 provided written consent and assent, as necessary. Overall, the retention rates were high: 82.4% (166 PHIV+ and 114 PHEU youths) between baseline and FU1, and 79% (166 PHIV+ and 104 PHEU) of youths who were initially enrolled in CASAH-1 were successfully recruited for CASAH-2. The median time interval between FU1 and FU2 was 3 years (Myears = 2.89, SD = 1.29). At FU2, youths’ ages ranged from 13 to 24 years (Mage = 16.73, SD = 2.74).

Due to missing data on one or several key covariates at follow-up, only 325 youths (196 PHIV+ and 129 PHEU) were included in these analyses. There were no significant differences by youths’ HIV status, gender, race/ethnicity, age, and mental health outcomes between the youths who completed follow-up interviews and those who were lost to follow- up. Among youths included in these analyses, we observed minimal but statistically significant differences in follow-up time (in years between assessments) by HIV status between baseline and FU1 (MPHEU =1.09, SD = 0.42, MPHIV+ = 1.28, SD = 0.63; t = −3.08, p = .005), and FU1 and FU2 (MPHEU =2.46, SD = 1.06, MPHIV+ = 3.19, SD = 1.35; t = −4.48, p < .001) due to greater loss to follow-up among older PHEU. Therefore, our analyses accounted for these potential differences by including age as a covariate in each statistical model and assessed differences in MHS by HIV status.

Measures

Mental health symptoms (MHS), were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; child version) (21), an extensively used and well-validated measure of DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses (22). MHS were aggregated into two symptom count scores: total internalizing symptoms and total externalizing symptoms.

Contextual factors included youths’ socio-demographics i.e. youths’ age, gender, HIV status, and type of caregiver (birth parent vs. non-birth parent caregiver). Youths’ HIV status was determined via medical charts and clinician verification. At baseline, youths self-identified their race based on their ethnic/cultural heritage (e.g., Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Caribbean French), and these were collapsed into four racial/ethnic categories (see Table 1): Non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and Other. Given the small distribution of Non-Hispanic Whites and Other Race/Ethnicity participants, these two categories were collapsed into a single race/ethnicity category in our multivariate analyses. Household poverty (living below or above the New York State poverty line) was based on household income adjusted for the number of household members. Environmental stressors included major life events and neighborhood stress. Major life events were assessed using an instrument developed at a mental health program for families affected by HIV (23). This 46-item checklist (our sample, α = .86) assesses events related to one’s family (e.g., increase arguments between parents), self (e.g., major illness), or peers (e.g., having a close friend with a drug problem). A total score was computed as the sum of the impact ratings of all items designated by the respondent as “bad”, with higher scores reflecting more adverse stressful life events. Neighborhood stress was measured using the City Stress Inventory (24), a 16-item index that assesses neighborhood disorder and exposure to violence (our sample, α = .86) using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = often). Neighborhood stress was computed as the mean score of these stressors. Caregiver HIV status, assessed using self-report data about personal HIV tests and results (HIV infected vs. uninfected/untested). Caregiver depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (25), a 21-item self-report measure of the presence and intensity of depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, loss of interest, guilt, suicidality, and vegetative changes (our sample, α =.89). Caregiver anxiety was assessed using the 20 item State anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (26), which assesses how the respondent feels at the moment (our sample α =.92).

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of youths stratified by HIV status (N = 325)

| Characteristic | PHIV+ youths | PHEU youths | t-test/χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | ||

| Age | 12.29 (2.18) | −1.403 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 98 (50.0) | 65 (50.4) | 0.01 | ||

| Females | 98 (50.0) | 64 (49.6) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black/African-American | 91 (46.7) | 58 (44.6) | 1.53 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Hispanic | 97 (49.7) | 68 (52.3) | |||

| Other | 5 (2.6) | 4 (3.1) | |||

| Type of caregiver | |||||

| Biological | 68 (34.7) | 90 (69.8) | 38.31*** | ||

| Non-biological | 128 (65.3) | 39 (30.2) | |||

| Household income | |||||

| Below NY poverty line | 134 (71.3) | 113 (90.4) | 16.50*** | ||

| Above NY poverty line | 54 (28.7) | 12 (9.6) | |||

| Future orientation | 0.08 (0.98) | 0.12 (1.03) | 1.73 | ||

| Caregiver Depression | |||||

| Baseline | 7.19 (7.16) | 8.82 (8.52) | 1.84 | ||

| FU1 | 7.53 (7.56) | 7.88 (7.70) | 0.36 | ||

| FU2 | 7.25 (6.68) | 9.08 (8.56) | 1.63 | ||

| Major life events | |||||

| Baseline | 6.40(5.95) | 6.10 (4.78) | −0.48 | ||

| FU1 | 12.51(14.88) | 10.59 (12.95) | −1.20 | ||

| FU2 | 12.70(13.88) | 15.95 (15.88) | 1.90 | ||

| Neighborhood stress | |||||

| Baseline | 9.87 (7.59) | 11.64 (9.01) | 1.85 | ||

| FU1 | 11.10 (8.74) | 11.79 (8.58) | 0.65 | ||

| FU2 | 13.58 (10.28) | 14.66 (9.70) | 0.85 | ||

| Internalizing symptoms | |||||

| Baseline | 19.51 (12.57) | 20.64 (14.08) | 0.76 | ||

| FU1 | 16.64 (12.17) | 14.91 (11.53) | −1.18 | ||

| FU2 | 16.33 (10.92) | 14.51 (10.60) | −1.35 | ||

| Externalizing symptoms | |||||

| Baseline | 14.82 (9.11) | 14.42 (10.09) | −0.37 | ||

| FU1 | 13.55 (9.93) | 12.25 (9.16) | −1.11 | ||

| FU2 | 14.70 (9.79) | 13.79 (9.79) | −0.78 | ||

p < 0.001

The Self-regulation included in these analyses was youths’ Future life orientation, assessed using items adapted from Monitoring the Future (27), which assesses youths’ perceptions about the probability of completing school, getting employment, getting married, having children, making money, and moving out of their neighborhood (our sample, α = 0.61).

Data Analytic Strategy

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the distribution of all variables at each time point, and assess relationships between variables. Caregiver HIV status and type of caregiver (i.e. birth parent) were confounded, reflecting the fact that 100% of birth mothers were by definition HIV-positive and almost all birth parents were the mother (we had very few fathers). Similarly, caregiver depression and caregiver anxiety were highly correlated. Therefore, caregiver HIV status and anxiety were not included in the analytic models.

We used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; v. 7.0) to fit multilevel linear growth curve models of the changes in MHS over time (28). We modeled changes in MHS over time by including variables at Level I (e.g. time, major life events, household poverty, caregiver mental health and neighborhood stress) and Level II (e.g. age, sex, race, race, ethnicity, HIV status, type of caregiver, and future orientation). Given that 30% of our sample had more than one participant per family, we also included having a sibling as a covariate in these analyses. We assessed variation in youths’ MHS across three waves of data collection, modeling change over time as a quadratic curve. In these models, we observed significant random effects in our intercept and growth term parameters, suggesting variability in the MHS trajectories in our sample. We then examined the influence of Level I and Level II variables on the change in MHS. At each step, we compared the deviance statistics for our multilevel models; changes in model fit statistically improved at each step. For brevity, we present our final models below. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses, we present findings below p < .10.

Results

Descriptive summary

Table 1 presents a summary of the baseline socio-demographic characteristics, internalizing symptoms, and externalizing symptoms for both PHIV+ and PHEU youths. There were no significant differences between PHIV+ and PHEU youths in age, gender, race, and ethnicity. The majority (78.9%) of youths (both PHIV+ and PHEU) were living below the New York State Poverty line but PHEU youths had slightly lower family incomes than PHIV+ youths, (18.2% vs. 18.8%; χ2 = 16.50; p ≤ .001). Overall, MHS decreased among PHIV+ and PHEU youths across time. Comparisons of MHS by HIV status at each time point (wave) were not statistically significant and changes in MHS did not differ by HIV status.

Internalizing symptom count

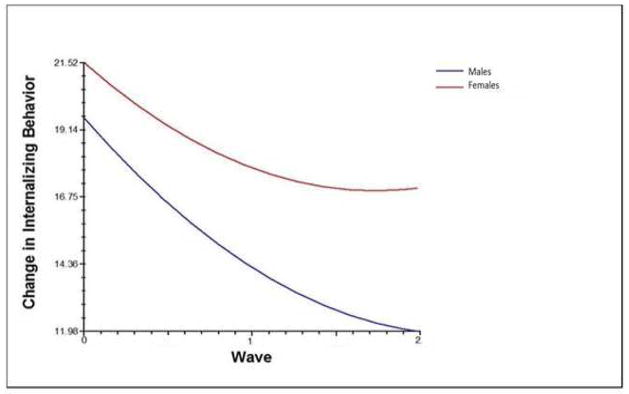

Youths’ internalizing symptoms at baseline were not significantly associated with the socio-demographic variables. The change in internalizing symptoms followed a quadratic growth curve (see Table 2), with the linear rate of change varying by youths’ sex (Figure 1): females reported greater increases in internalizing symptoms over time than males (β = 1.53 (SE = 0.89); p = .08). Among the Level I covariates (Table 2), increases in internalizing symptoms were associated with major negative life events (β = 0.38 (SE = 0.11); p < .001) and neighborhood stressors (β = 0.28 (SE = 0.06); p < .001). Youths’ HIV status and caregiver depression were not significantly associated with prospective changes in internalizing symptoms. Compared to the null model (Deviance=6,724.91), our final model was found to have a better model fit (Deviance=5,468.24; p < .001).

Table 2.

Prospective changes in mental health symptoms among PHIV+ and PHEU youths (N=325)

| Internalizing Symptoms | External Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effect | b | SE | p-value | b | SE | p-value |

| Mean Score at Wave 0, β00 | 23.68 | 4.19 | <0.001 | 10.38 | 3.11 | <0.001 |

| Age at Baseline, β01 | −0.13 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| HIV-Positive, β02 | −2.14 | 1.47 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.08 | 0.92 |

| Females, β03 | 2.06 | 1.30 | 0.11 | −2.45 | 0.95 | 0.01 |

| CG is bioparent, β04 | −2.03 | 1.44 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.04 | 0.89 |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American, β05 | −1.04 | 2.90 | 0.72 | 1.80 | 1.70 | 0.29 |

| Hispanic, β06 | 3.20 | 2.96 | 0.28 | 2.58 | 1.73 | 0.14 |

| Baseline Future Orientation (z-score), β07 | −0.69 | 0.64 | 0.28 | −1.10 | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| Family ID, β08 | −1.75 | 1.18 | 0.14 | −0.63 | 0.89 | 0.48 |

| Linear Change across Waves, β10 | −8.97 | 2.36 | <0.001 | −2.16 | 2.11 | 0.31 |

| HIV-Positive, β12 | 1.33 | 0.90 | 0.14 | −0.14 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| Females, β13 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 1.78 | 0.73 | 0.02 |

| CG is bioparent, β14 | −0.16 | 0.92 | 0.94 | −1.16 | 0.78 | 0.14 |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American, β15 | 1.89 | 1.97 | 0.34 | −0.96 | 1.68 | 0.57 |

| Hispanic, β16 | 1.07 | 1.97 | 0.59 | −0.96 | 1.74 | 0.58 |

| Baseline Future Orientation (z-score), β17 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| Quadratic Change across Waves, β20 | 1.55 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 1.07 | 0.54 | 0.05 |

| Living in Poverty Over Time, β30 | 0.64 | 1.09 | 0.55 | 1.12 | 0.83 | 0.18 |

| Caregiver Depression Over Time, β40 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.50 |

| Environmental Stressors Over Time, β50 | 0.28 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Count of Negative Life Events Over Time, β60 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.39 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Prospective changes in youths’ internalizing symptoms stratified by sex

Externalizing symptom count

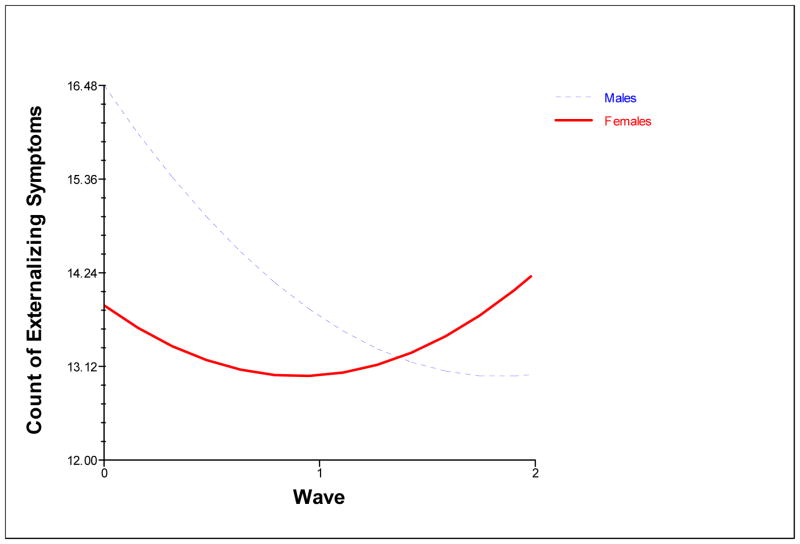

Baseline externalizing symptoms were significantly associated with the youths’ age, sex and future orientation scores. Older youths reported greater externalizing symptoms at baseline (β = 0.35 (SE = 0.17); p = .04). Female youths (β = −2.45 (SE = 0.95); p = .01) and youths with higher future orientation scores (β = −1.10 (SE = 0.47); p = .02) reported fewer externalizing symptoms at baseline. The change in externalizing symptoms followed a quadratic growth curve (Table 2). As shown in Figure 2, youths’ sex modified the linear rate of change over time: overall, females were more likely than males to report an increase externalizing symptoms (β = 1.78 (SE = 0.73); p = .02). Among the Level I covariates (Table 2), externalizing symptoms were significantly associated with major negative life events (β = 0.39 (SE = 0.09); p < .001) and neighborhood stressors (β = 0.23 (SE = 0.05); p < .001). Youths’ HIV status and caregiver depression were not significantly associated with prospective changes in the externalizing symptoms. Compared to the null model (Deviance=6,265.09), our final model was found to have a better model fit (Deviance=5,131.14; p < .001).

Figure 2.

Prospective changes in youths’ externalizing symptoms stratified by sex

Discussion

Understanding the changes and correlates of MHS among PHIV+ and PHEU youths in the United States is critical to developing effective preventive and treatment interventions that promote their well-being. This study sought to expand the current literature on the mental wellbeing of PHIV+ and PHEU youths by utilizing longitudinal analyses to characterize changes in MHS among PHIV+ and PHEU youths as they transition through adolescence, and to identify the risk and protective factors associated with these changes.

We explored the role of perinatal HIV status in shaping the trajectories of MHS in PHIV+ and PHEU youths. We found no evidence to suggest that the changes in MHS differ between PHIV+ and PHEU youths during adolescence. The changes in MHS, however, varied with youths’ age, sex, number of negative life events, and neighborhood stressors experienced. At baseline, older participants reported greater externalizing symptoms than younger counterparts and, consistent with prior studies, the number of externalizing symptoms decreased as youths transitioned through adolescence (29). Our findings suggest that contextual factors, rather than HIV status, impact the mental well-being of PHIV+ and PHEU youths.

Similar to prior studies, we found that female youths were more likely to report internalizing symptoms compared to male youths (30–32). We also found that although female youths reported fewer externalizing symptoms at baseline, they had a greater rate of increase in externalizing symptoms compared to male youths, who reported a decline in externalizing symptoms over time. The mechanisms that underlie these gender differences in the emergence of MHS during adolescence remain largely unknown, although some researchers assert that female youths may carry more risk factors for MHPs even before early adolescence including genetic, personality and environmental adversity (e.g. sexual trauma, victimization, gender intensification in adolescence), which result in greater rates of MHPs in the face of adversity (31–33). Therefore, these findings indicate that PHIV+ and PHEU female youths may be more vulnerable to MHPs compared to their male counterparts.

Consistent with reports from prior studies conducted among youths, both HIV-infected and HIV non-infected, changes in MHS over time were positively associated with the number of negative life events and neighborhood stressors experienced (13, 34–36). Although we did not find any statistically significant differences by HIV status on youths’ neighborhood stressors and negative life event scores, the impact of neighborhood stressors and stressful live events may be qualitatively different for PHIV+ and PHEU youths. Taken together, our data suggest that PHIV+ and PHEU youths would greatly benefit from existing community and structural interventions that to address the myriad of risk factors that increase vulnerability to MHPs and promote adaptive coping. However, a review of such interventions is beyond the scope of this paper. The variations in risk factors for MHPs through adolescence underscore the need for a nuanced life course approach that recognizes youths as a population in transition, encountering new challenges and opportunities, which necessitate developing and/or mastering new skills. As such, dynamic interventions that seek to identify and address emerging threats and opportunities are needed.

The observed lack of association between race/ethnicity, household poverty, caregiver mental health, and MHS stands in contrast to the broader literature on mental health among youth (35, 37). The lack of association between youth’s race/ethnicity, household poverty and MHS could be attributed to lack of variation on these variables in our sample, which comprised largely of ethnic minority youths living in poverty. Moreover, both race/ethnicity and low socioeconomic status are strongly associated with HIV in the U.S. (9). The lack of association between caregiver mental health and youths’ MHS could be attributed to developmental changes in youths’ spheres of influence. Adolescence is a time for transformation of adolescent-caregiver relationships (38, 39); as adolescents establish relationships with peers and significant others outside the family, they encounter a myriad of challenges that could impact their wellbeing and also expand their repertoire of coping skills and resources (39, 40). Therefore, major life events and neighborhood stressors may be more important than caregiver related factors during this developmental stage.

These findings should be interpreted within the limitations of this study. Study participants were recruited from primary HIV care clinics so the findings may not be generalizable to youths in other settings. We recruited and interviewed 76% of the eligible participants in the study recruitment sites, but this convenience sample may not reflect the large population of PHIV+ and PHEU youths, particularly those outside of NYC and youths who are not followed in HIV clinics. Although we attempted to recruit PHIV+ and PHEU youths from similar communities based on the demographics of pediatric HIV disease, other factors (e.g. access to services) may have altered group effects. Due to human subjects protections, we were did not collect data on patients who refused contact so we are not in a position to adjust our analyses for any recruitment bias. This study also utilized self-report instruments, which are susceptible to reporting bias. Lastly, we did not explore the role of biological/genetic and social regulation factors, which could influence youths’ MHS. Despite these limitations, our findings have several important clinical and policy implications as they provide important insights into the long term changes in youths’ MHS, and highlight sources of persistent vulnerability.

Our findings underscore the need to reduce or eliminate exposure to major life events and neighborhood stressors among PHIV+ and PHEU youths whenever possible and to improve youths’ ability to cope with these events. Development of contextually relevant interventions requires concerted attention to identifying the factors that confer resilience against the varied detrimental factors that PHIV+ and PHEU youths may experience. Therefore, future studies to identify the psychosocial resources that may confer resilience among PHIV+ and PHEU youths and examine biological/genetic factors that influence MHPs would additionally expand our understanding of the complex inter-play between bio-genetic, psychosocial and neighborhood factors, especially among youths’ living in contexts of heightened vulnerability. To further understanding of the vulnerability of PHIV+ and PHEU youths, future studies should also explore whether neighborhood factors and negative life events may have different impacts among PHEU youths compared to unexposed youth.

Implications and contribution

These findings highlight the centrality of contextual factors such as negative life events and neighborhood stressors in the evolution of mental health problems among perinatally HIV-infected and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected youths as they transition through adolescence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH63636; PI: Claude Ann Mellins, Ph.D.), and a center grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (P30MH43520; Center PI: Robert H Remien, Ph.D.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu CS, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Leu C-S, et al. Prevalence and change in psychiatric disorders among perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-exposed youth. AIDS care. 2012;24:953–962. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharko A. DSM psychiatric disorders in the context of pediatric HIV/AIDS. AIDS care. 2006;18:441–445. doi: 10.1080/09540120500213487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Brackis-Cott E, et al. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-exposed youth: roles of caregivers, peers and HIV status. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2009;45:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malee KM, Williams PL, Montepiedra G, et al. The role of cognitive functioning in medication adherence of children and adolescents with HIV infection. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2009;34:164–175. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, et al. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: The role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2008;33:1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013:16. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benton TD. Psychiatric considerations in children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58:989–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C. Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence---24 cities. United States: 2011. 2006–2007. Report No.: 1545-861X. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E, Mellins CA, Dolezal C, et al. Disadvantaged neighborhood influences on depression and anxiety in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus: how life stressors matter. Journal of community psychology. 2011;39:956–971. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, et al. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1533–1544. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.575120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gadow KD, Angelidou K, Chernoff M, et al. Longitudinal study of emerging mental health concerns in youth perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparisons. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 2012;33:456. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31825b8482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Williams PL, et al. Co-occuring psychiatric symptoms in children perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31:116. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cdaa20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misdrahi D, Vila G, Funk-Brentano I, et al. DSM-IV mental disorders and neurological complications in children and adolescents with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection (HIV-1) European Psychiatry. 2004;19:182–184. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bomba M, Nacinovich R, Oggiano S, et al. Poor health-related quality of life and abnormal psychosocial adjustment in Italian children with perinatal HIV infection receiving highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS care. 2010;22:858–865. doi: 10.1080/09540120903483018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colman I, Wadsworth ME, Croudace TJ, et al. Forty-year psychiatric outcomes following assessment for internalizing disorder in adolescence. 2007 doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental perspective on internalizing and externalizing disorders. Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction. 1991;2:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. American Psychologist. 1991;46:931. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seiffge-Krenke I, Aunola K, Nurmi JE. Changes in stress perception and coping during adolescence: The role of situational and personal factors. Child development. 2009;80:259–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seginer R. Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: How resilient adolescents construct their future. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychological Association A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellins CA, Havens J, Kang E. Child psychiatry service for children and families affected by the HIV epidemic. IX International AIDS Conference; Berlin, Germany. 1993; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: development and validation of a Neighborhood Stress Index. Health Psychology. 2002;21:254. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT. Beck depression inventory. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch R. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults: Manual and Sample: Manual, Instrument and Scoring Guide. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson LD, O’Malley P, Bachman J. National survey results on drug use from the monitoring the future study, 1975–1997. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan Y-F, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of affective disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current directions in psychological science. 2001;10:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological bulletin. 1994;115:424. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological bulletin. 2001;127:773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang E, Mellins CA, Ng WYK, et al. Standing between two worlds in Harlem: A developmental psychopathology perspective of perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus and adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological bulletin. 2000;126:309. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, et al. Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV-infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124:627–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. American Psychologist. 2012;67:272. doi: 10.1037/a0028015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muuss RE. Theories of adolescence. Crown Publishing Group/Random House; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piaget J. Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human development. 1999;15:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of adolescent Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]