Abstract

The cusps of native Aortic Valve (AV) are composed of collagen bundles embedded in soft tissue, creating a heterogenic tissue with asymmetric alignment in each cusp. This study compares native collagen fiber networks (CFNs) with a goal to better understand their influence on stress distribution and valve kinematics. Images of CFNs from five porcine tricuspid AVs are analyzed and fluid-structure interaction models are generated based on them. Although the valves had similar overall kinematics, the CFNs had distinctive influence on local mechanics. The regions with dilute CFN are more prone to damage since they are subjected to higher stress magnitudes.

Keywords: collagen fibers, porcine specific, numerical model, fluid-structure interaction, aortic valves

Introduction

The aortic valve (AV) is located between the left ventricle and the aorta and consists of three cusps and three sinuses. The tissue of the cusps consists of mainly elastin, collagen, and glycosaminoglycans, where the strong collagen fiber bundles are distributed asymmetrically, but aligned mainly in the circumferential direction. It is well known that the cusps’ circumferential direction is stiffer than the radial one (Billiar & Sacks 2000, Stella et al. 2007). Similarly, the asymmetric fiber distribution (Balguid et al. 2008, Missirlis & Chong 1978) may affect the AV’s local mechanical properties.

Since each cusp has a unique asymmetric collagen fiber network (CFN), several attempts have been made towards patient specific description of its structure. Several groups (Balguid et al. 2008, Robinson et al. 2008, Rock et al. 2014, Sacks et al. 1998) have studied the complex fiber network using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and small angle light scattering (SALS). Balguid et al. (2008) found a relation between the stress magnitudes and the local fibers diameter and density.

Numerical models were also employed to investigate the native tissue mechanics. These models included both structural finite element analysis (FEA) (Grande et al. 1998, Kim et al. 2008, Sun & Sacks 2005, Sun et al. 2003), and fluid-structure interaction (FSI) models (Marom et al. 2012, Nicosia et al. 2003). Most of them modeled the tissue’s nonlinear anisotropic behavior with constitutive models (Kim et al. 2008, Sun & Sacks 2005, Sun et al. 2003). Our group (Marom et al. 2013b) previously suggested a heterogeneous modeling approach with two separate element layers for the CFN and for the soft tissue matrix. The CFN was physiologically distributed and both layers had isotropic hyperelastic response. Driessen et al. (2005) suggested to calculate fibers’ orientation from the deformation tensor rather than experimental results. Loerakker et al. (2013) implemented this model to assess the influence of valve geometry and tissue anisotropy on tissue engineered heart valves. Several parametric FEA (Cacciola et al. 2000, De Hart et al. 1998, Liu et al. 2007) and FSI (De Hart et al. 2004) studies were investigated the fibers orientation, volume fraction and density for designing purposes. Lowest principle stresses were obtained for fiber orientation of 60° with respect to the horizontal axis. Similar demonstration for the influence of fiber volume and orientation on valve kinematics and stress distribution can also be found in the multiscale models of Weinberg & Mofrad (2007).

Most numerical studies assumed symmetric alignment, while some the asymmetry was usually addressed by morphological geometry (Conti et al. 2010, Grande et al. 1998, Jermihov et al. 2011, Marom et al. 2013a). Loerakker et al. (2013) tested different degrees of anisotropy, yet their material models were homogenous. In our recent study (Marom et al. 2013b), we performed a numerical comparison of the hemodynamics in two valves with identical geometry but different CFNs, symmetric and porcine specific. These FSI models showed the importance of the AV asymmetry and its effect on the blood flow.

While it has been shown that native asymmetric fibers alignment in AVs affects the hemodynamics, the influence on stress distribution and valve kinematics have not been investigated yet. Moreover, a detailed comparison of various porcine specific CFNs has not been documented. The aims of this study are to determine the effects of local fiber bundles’ alignment on the kinematics and the stress distribution in the CFN and the soft tissue. First, CFNs of five different porcine AVs have been mapped, compared and used to generate five porcine specific FSI models. Finally, the valves’ openings and the spatial stress distributions for each cusp are compared.

Methods

Tissue Preparation and Tissue Imaging

Five AVs were obtained from five different porcine specimens at the age of six months. This research was approved by the institutional ethics committee for animal experiments and all cusps were obtained from Neufeld Cardiac Research Institute at the Sheba Medical Center. All five valves contained three cusps, left, right, and non-coronary (LC, RC, and NC). The cusps were dissected and preserved separately in a 3% formaldehyde solution for 100–120 hours to make the collagen bundles visible.

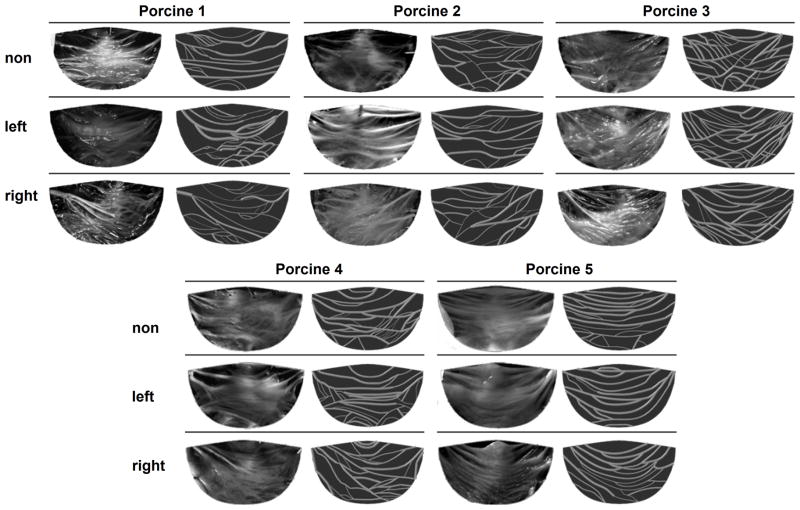

All fifteen cusps were imaged and mapped. The images were taken from the aortic side of the fixed and flattened cusps using a digital microscope with a magnification of ×10 (DinoLite AM311ST, AnMo Electronics, Hsinchu, Taiwan). The CFN location and local bundle diameter was measured and mapped with a graphic digitizing code. A Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) code was written to locate and smooth the branches representation. Images of the 15 cusps with their equivalent mapped CFNs are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Images of right, left and non-coronary cusps from five different porcine valves and the equivalent mapped collagen fibers networks

Computational Model

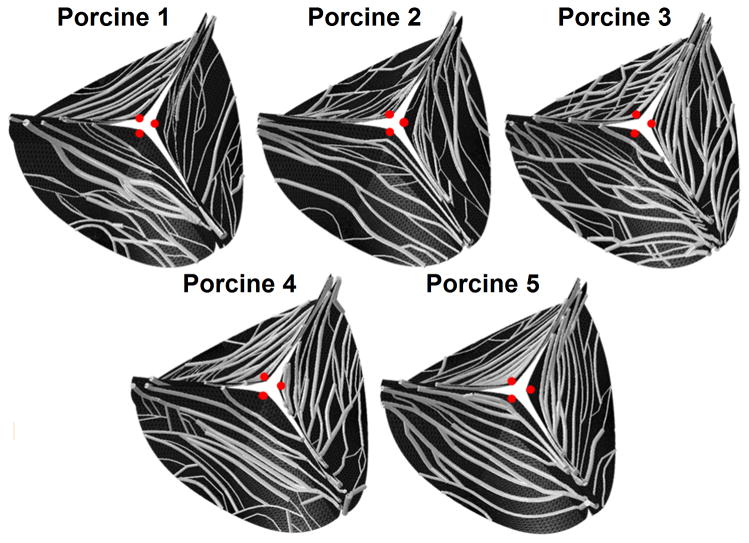

A three dimensional (3-D) geometry of the structural model was reconstructed using an idealized AV geometric model with porcine AV dimensions (Haj-Ali et al. 2012) (Marom et al. 2013b). The mapped CFNs were transformed to this initial geometry while keeping the relative locations of the CFN nodes on the cusps’ elements (Marom et al. 2013b), as shown in Figure 2. Therefore, the valve model consists of three symmetrical and identical sinuses and cusps but with porcine-specific mapped CFN bundles. The structural solver employed an implicit nonlinear dynamics using FEA. Shell elements were used for meshing the root and the soft tissue matrix of the cusps, while the collagen bundles were meshed with circular beam elements (Marom et al. 2013b). A root thickness of 2 mm was defined based on available data for porcine roots (Gundiah et al. 2008). The soft tissue matrix had a uniform thickness of 0.3 mm (Marom et al. 2013b) and the collagen bundles radii were between 0.05–0.14 mm based on the local measurements. The shell mesh was created with TrueGrid (XYZ Scientific Applications, Livermore, CA, USA) and had more than 14,000 elements following a mesh refinement study (Marom et al. 2012). The CFN mesh added between 670 to 1279 nodes to each valve. All the degrees of freedom of these nodes were forced to be equal to those of the shell elements. The cusp tissue was modeled using a CFN material model (Kim 2009) that explicitly recognized the collagen fibres and the soft tissue matrix using different layers of elements. The two layers are coupled in all their degrees of freedom and bundles cannot slip with respect to the soft tissue (Billiar & Sacks 2000). Effective material properties of the collagen and the soft tissue were previously calibrated according to experimental data of native porcine valves (Kim 2009, Marom et al. 2013a, Marom et al. 2013b, Missirlis & Chong 1978). The aortic root was assumed isotropic and hyperelastic with mechanical behavior from available data (Gundiah et al. 2008). Coaptation between the cusps was modeled with master-slave contact algorithm (Marom et al. 2012).

Figure 2.

Geometric re-construction of three dimensional collagen fibers networks for the five mapped valve models – an aortic side view

A finite volume method, with a Cut-Cell Cartesian mesh (Marom 2014), was used to solve the unsteady 3-D Navier-Stokes and mass conservation equations. The fluid domain was discretized with dynamically adapting mesh of approximately 700,000 cells (Marom et al. 2012). The flow boundary conditions were moved away from the regions of interest by adding straight and rigid tubes (Marom et al. 2012). Physiologic time-dependent left ventricular and aortic pressures were employed at the boundaries (Marom et al. 2013b). The blood flow was assumed laminar with Newtonian fluid at a temperature of 37°C (Marom et al. 2012).

The FSI models were solved by a partitioned solver with non-conformal meshes. The sequential two-way loose coupling process exchanged the structure displacement and the flow traction between the solvers (Marom et al. 2012). Virtual surfaces were added to represent the cusps’ thickness (Marom et al. 2013a). The maximum time steps defined in the model were 2.5 ms and 1.25 ms for the flow and structural solvers, respectively (Marom et al. 2012). The solvers were Abaqus 6.11 (Simulia, Providence, RI, USA) and FlowVision 3.08 (Capvidia, Leuven, Belgium) for the structure and flow, respectively.

Data Analysis

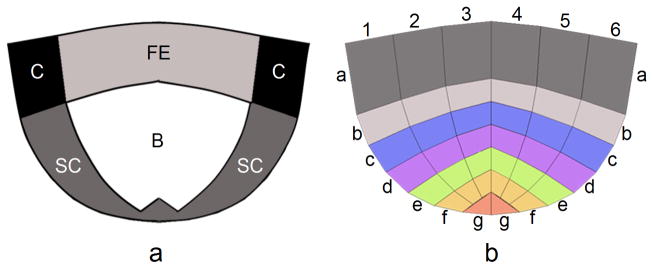

Each stretched cusp was divided into four main regions namely: commissures, free-edge, belly and sub-commissure (Figure 3a). The cusps were then divided into 38 subregions marked by their longitudinal (a–g) and circumferential (1–6) locations (Figure 3b). The averaged maximum principle stresses, at each region and sub-region, were calculated for the soft tissue and the collagen separately. These averages were calculated by a Matlab code based on structural stress results. The results were compared and analyzed with univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test while a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. The opening area of each valve and the radial displacement in the middle of the free edge of each cusp (red dots in Figure 2) were calculated as for every time step.

Figure 3.

Illustration of a cusp and the locations of: (a) four main regions (C - commissures, FE - free-edge, B - belly, SC - sub-commissure) and (b) 38 subregions. The sub-regions are marked by their longitudinal (a–g) and circumferential (1–6) locations

Results

This section presents the measured fiber area fraction (FAF) and orientation of the fiber bundles, as well as the calculated principal stresses and valve kinematics from the FSI models. First, the measured volume and orientation data will be compared, followed by comparison of stress results from the diastolic phase. Finally, kinematical results are presented throughout the cardiac cycle.

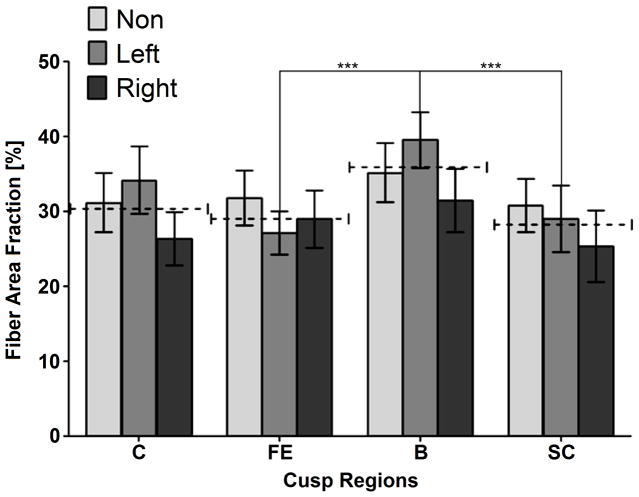

Figure 4 shows the mean local FAFs for each region (Figure 3a) and cusp type. The FAF is defined here as the ratio of the collagen bundles section area to the matrix’s total area. In every region, no significant difference was found between the three cusp types (p<0.05). Still, in all regions except the free edge the mean FAF of the right cusp is lower than the other two cusps. The mean FAF was found to be between 28.4±9.1% to 35.4±8.8%. The average value of the three cusps (marked as dashed lines in Figure 4) shows a statistical difference with higher FAF in the belly region compared to the sub-commissure and free edge regions. The fiber total concentration is calculated for each valve by averaging the FAFs of its three cusps. It is worth noticing that the fiber total concentrations vary significantly between the five measured valves, with values between 24.2% and 40.3%, for specimens 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 4.

Collagen fiber area fraction of the different cusp types (non, left and right-coronary) at the different regions (C - commissures, FE - free-edge, B - belly, SC- sub-commissures). Dashed lines mark the average value between the three cusps types. Statistical difference between these average values (p<0.05) is marked by “***”

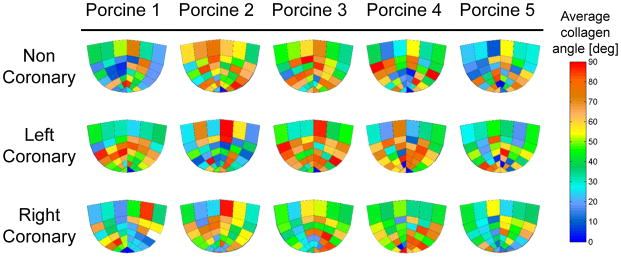

The calculated averaged collagen bundles’ orientation angles are plotted in Figure 5 for each sub-region and cusp type. Although asymmetrical distribution of the collagen orientation can be clearly seen, these differences are not statistically significant when comparing the angles at each sub-region and cusp type. The global averaged angle is in the range of 36°–59° in all the cusps, similar to previous findings by Liu et al. (2007). A relation between the angle and circumferential location is found for all 15 cusps. Close to the free edge (stripes a and b in Figure 3b), the angle are highest in the middle of the cusp and lowest near the sides. Closer to the base of the cusp (stripes e and f in Figure 3b), an opposite trend is observed with lower angles in the middle of each stripe.

Figure 5.

Average fiber orientation angle for different cusp types at 38 sub-regions within each cusp

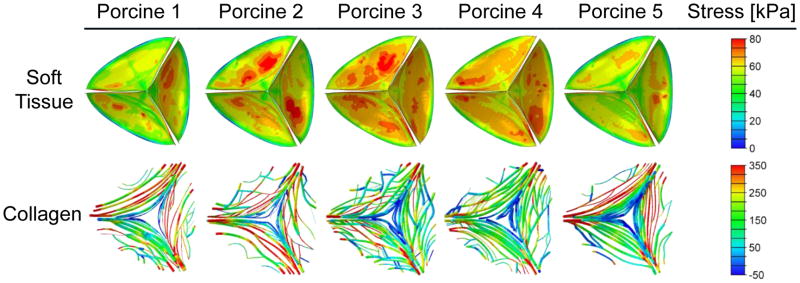

Principal stresses in the tissues were calculated from the FSI models for both the matrix and the collagen bundles. Figure 6 shows the non-homogeneous stress distributions that were found in all the models during the diastole (at time of 260 ms). Mean stress magnitudes, both in the soft tissue and the collagen, were compared at different regions and cusp types. The stress values in the collagen fibers are significantly higher (p<0.05) than the soft tissue stress values, at all regions and for all cusp types. The highest stresses in the soft tissue matrix are found in the commissures region (63.4–71.4 kPa) and are significantly higher than other regions. The stresses in the free edge and belly regions of the soft tissue are similar and significantly higher than the sub-commissure stresses (30–36.9 kPa compared to 19.9–22.5 kPa, respectively). The lowest collagen stresses are found in the free-edge region (103–116 kPa). The collagen stresses in commissures and belly regions are similar (234–246 kPa and 192–279 kPa, respectively) and significantly higher than the sub-commissure stresses (192–208 kPa). The highest mean stress values are found in the right cusp at all regions except for the commissure region of the collagen fibers. Comparison of the stresses in the 38 sub-regions demonstrates the important role of the fibers. While the soft tissue stress has only moderate spatial gradients, stress concentrations are found in several sub-regions of the CFN, mainly in the belly regions of the right and non-coronary cusps. Obviously, these local high stresses are caused by the local CFN structure. Spatial trends of the stress distribution, which are related to the bundles’ orientation, are found in all the 15 cusps. Lower stress magnitudes are found in the free edge and sub-commissure regions, where a larger angles (50°–60°) were observed. On the other hand, the highest stresses are in the commissures and belly regions, where the angles are between 30° and 40°. These findings are in accord with published results (Liu et al. 2007) that showed maximum tissue stress reduction for fibers oriented in 60°.

Figure 6.

Stress contours during diastole (time of 260 ms) for the soft tissue matrix and the collagen fiber bundles as calculated for the five porcine-specific mapped models

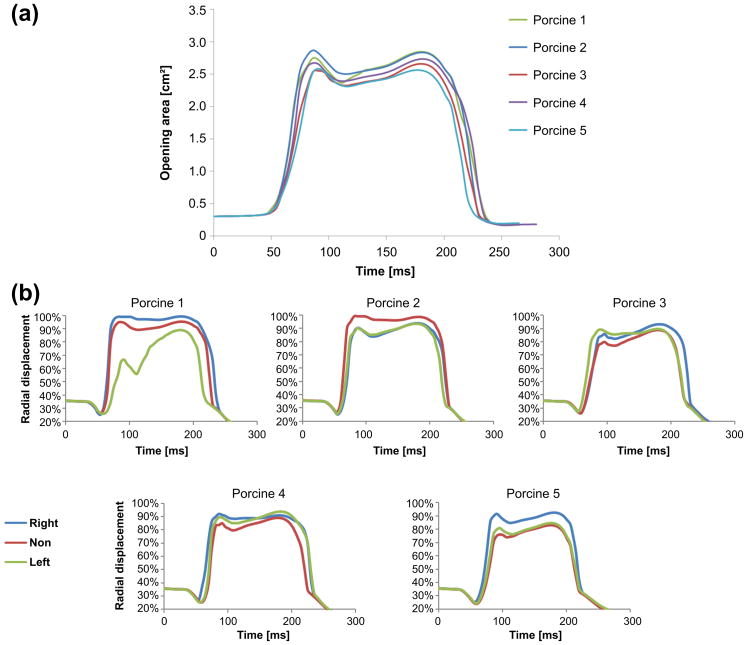

The opening area of each valve as a function of time is plotted in Figure 7a. The opening areas are similar for all five models throughout the cardiac cycle. At peak systole, defined here as the first time the valve reaches its maximum opening state, the opening area of the valves are between 2.55 and 2.86 cm2 for the models of specimens 3 and 2, respectively. The peak systole of three models (1, 2 and 4) occurs 86 ms after the beginning of the opening, while it occurs 5 ms later in the other two models. These opening times are very close to the range of 74 to 90 ms that was previously found for AVs under a heart rate of 70 bpm, both in in-vivo measurements of dogs (Higashidate et al. 1992) and in FEA models (Jermihov et al. 2011). Systole continues until the valve started to close 85–95 ms after the beginning of systole. These findings are also in the range previously published data (Higashidate et al. 1992, Jermihov et al. 2011). Closure duration of 70–74 ms is found for all models, in agreement with previous results of 70–90 ms (Higashidate et al. 1992, Jermihov et al. 2011). Figure 7b shows the radial displacement in the middle of the free edge of each cusp (marked with red dots in Figure 2) as function of time. The displacements of most of the models are similar, where the only exception is the left cusp in the first model. These radial displacements can also be used to define the peak systole. Based on this definition the peak systole of all the valves are between 86 to 96 ms after the beginning of the opening.

Figure 7.

(a) Valve opening area as a function of time for the five models; (b) Normalized radial displacement of the middle node of the free edge relative to the annulus radius as a function of time

Discussion

It is well known that the tissue of native AV cusps is composed of collagen fiber bundles and that they have a major effect on overall mechanical properties. In the current study, five valve-specific asymmetric CFNs were mapped from porcine specimens. These CFNs were employed in five similar FSI models based on our previously published approach for modeling native AVs (Marom et al. 2013b). Identical and idealized geometry was used for all the cases to better focus on the effect the specific CFN had on the valve functionality while eliminating the influence of the specific geometry. Although the models are not compared to dedicated experiential studies, they are in agreement with previous kinematical results under similar heart rate conditions. Specifically, the maximum opening area and the timing of the valve opening and closing are in the same range found in previous experimental and numerical studies (Higashidate et al. 1992, Jermihov et al. 2011).

Despite the visual differences in the collagen networks, no major statistical differences were found between the five valves. This statistical analysis considered the measured FAF and the averaged orientation angle. By dividing the cusps into 38 subregions, the local asymmetry of the bundles distribution was clearly observed, but the different cusps did not share a specific pattern. The circumferentially alignment of the bundles was observed both globally and locally. Another similarity to previous results is the high stresses in the belly and commissure regions that were also found for polymeric (Chandran et al. 1991) and native (Sabbah et al. 1986) valves. It may be noted that in all 15 cusps the network is denser in the belly region. This leads to the conclusion that this region is stiffer in all the cusps and may explain how this region withheld the higher pressure loads relative to the other regions.

In this study, the separated soft tissue and collagen modelling make it easier to calculate the stress distribution for each layer. The asymmetry did not affect the stresses significantly but different stresses were found for each CFN. The collagen bundles carry most of the load and are subjected to higher stress magnitudes as has also been shown in previous studies (Cacciola et al., De Hart et al. 1998). The significantly higher collagen stress magnitudes, up to 3.2–3.8 times the soft tissue stresses in the commissure region, appear in all the sub-regions of the cusps. A direct relation was found between the collagen bundles’ local orientation and local stress; the lower stress magnitudes are found where the angle is relatively large (50°–60°). Similar relation has not been found between the local FAF and the stress distribution. A possible explanation might be that since the collagen bundles are much stiffer than the surrounding soft tissue, they would carry most of the stress even if there are fewer fibers in the region. Therefore, the bundle orientation has more influence on the stress distribution than its cross sectional area.

The CFN structure also affects the cusp kinematics. Intuitively, valves with lower fiber content should reach a larger opening area faster and their systole should last longer. In the present study, no significant differences were found as a result of asymmetry, yet the calculated opening areas are indeed affected by various fiber concentration and distribution in the cusps of the different specimens. Valves with denser fiber networks have smaller opening area except for cases with very close fiber concentration (specimens 4 and 5 with concentration of 34.1% and 34.5%, respectively). Similarly, the local collagen bundle structure is probably also the cause of the differences in the radial displacements. For example, the left cusp in specimen 1 has higher FAF in its belly region than the other two cusps of the same valve. It makes the left cusp stiffer and reduces its radial displacement (Figure 7b). However, the displacement of the other two cusps compensate for this phenomena and an opening area similar to the other specimens is achieved (Figure 7a). The angular direction of the fibers also affects the radial displacement. The results of specimen 5, for example, demonstrate that a more gradual spatial change in the fiber orientation (in the right coronary cusp) may lead to slightly larger radial displacements (Figures 5 and 7b).

In conclusion, the present study introduces an imaging analyses and mapping of porcine-specific CFNs from five tricuspid AVs. These CFNs are employed in five full 3D-FSI models that produced physiologic mechanical and kinematical results. A correlation between the local collagen orientation angle and the local stress distributions was found. Cusps with higher collagen content had smaller opening area with shorter systole duration. The local fibers distribution had minor influence on the opening area and opening timing of the valves, but it affects the local kinematics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. David Castel from Neufeld Cardiac Research Institute at Sheba Medical Center and Lital Abraham from the Animal Facility of the Sackler Faculty of Medicine at Tel Aviv University, who provided the valves for this study and also helped to dissect them.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Balguid A, Driessen NJ, Mol A, Schmitz JP, Verheyen F, Bouten CV, Baaijens FP. Stress related collagen ultrastructure in human aortic valves--implications for tissue engineering. J Biomech. 2008;41:2612–2617. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiar K, Sacks M. Biaxial mechanical properties of the natural and glutaraldehyde treated aortic valve cusp-Part I: Experimental results. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:23–30. doi: 10.1115/1.429624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola G, Peters GW, Schreurs PJ. A three-dimensional mechanical analysis of a stentless fibre-reinforced aortic valve prosthesis. J Biomech. 2000;33:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran KB, Kim SH, Han G. Stress distribution on the cusps of a polyurethane trileaflet heart valve prosthesis in the closed position. J Biomech. 1991;24:385–395. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90027-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti CA, Della Corte A, Votta E, Del Viscovo L, Bancone C, De Santo LS, Redaelli A. Biomechanical implications of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve: a finite element study of aortic root function from in vivo data. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hart J, Cacciola G, Schreurs PJ, Peters GW. A three-dimensional analysis of a fibre-reinforced aortic valve prosthesis. J Biomech. 1998;31:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hart J, Peters GW, Schreurs PJ, Baaijens FP. Collagen fibers reduce stresses and stabilize motion of aortic valve leaflets during systole. J Biomech. 2004;37:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen NJ, Bouten CV, Baaijens FP. Improved prediction of the collagen fiber architecture in the aortic heart valve. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:329–336. doi: 10.1115/1.1865187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande KJ, Cochran RP, Reinhall PG, Kunzelman KS. Stress variations in the human aortic root and valve: the role of anatomic asymmetry. Ann Biomed Eng. 1998;26:534–545. doi: 10.1114/1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundiah N, Kam K, Matthews PB, Guccione J, Dwyer HA, Saloner D, Chuter TA, Guy TS, Ratcliffe MB, Tseng EE. Asymmetric mechanical properties of porcine aortic sinuses. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1631–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Ali R, Marom G, Ben Zekry S, Rosenfeld M, Raanani E. A general three-dimensional parametric geometry of the native aortic valve and root for biomechanical modeling. J Biomech. 2012;45:2392–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashidate M, Tamiya K, Kurosawa H, Imai Y. Role of the septal leaflet in tricuspid valve closure. Consideration for treatment of complete atrioventricular canal. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:1212–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermihov PN, Jia L, Sacks MS, Gorman RC, Gorman JH, 3rd, Chandran KB. Effect of Geometry on the Leaflet Stresses in Simulated Models of Congenital Bicuspid Aortic Valves. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2011;2:48–56. doi: 10.1007/s13239-011-0035-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Lu J, Sacks MS, Chandran KB. Dynamic simulation of bioprosthetic heart valves using a stress resultant shell model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:262–275. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS. Nonlinear multi-scale anisotropic material and structural models for prosthetic and native aortic heart valves. Atlanta, GA, USA: Georgia Institute of Technology; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kasyanov V, Schoephoerster RT. Effect of fiber orientation on the stress distribution within a leaflet of a polymer composite heart valve in the closed position. J Biomech. 2007;40:1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerakker S, Argento G, Oomens CW, Baaijens FP. Effects of valve geometry and tissue anisotropy on the radial stretch and coaptation area of tissue-engineered heart valves. J Biomech. 2013;46:1792–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom G. Numerical Methods for Fluid–Structure Interaction Models of Aortic Valves. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2014 Epub 2 Oct 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marom G, Haj-Ali R, Raanani E, Schafers HJ, Rosenfeld M. A fluid-structure interaction model of the aortic valve with coaptation and compliant aortic root. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2012;50:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s11517-011-0849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom G, Kim H, Rosenfeld M, Raanani E, Haj-Ali R. Fully coupled fluid-structure interaction model of congenital bicuspid aortic valves: effect of asymmetry on hemodynamic. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2013a:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11517-013-1055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom G, Peleg M, Halevi R, Rosenfeld M, Raanani E, Hamdan A, Haj-Ali R. Fluid-structure interaction model of aortic valve with porcine-specific collagen fiber alignment in the cusps. J Biomech Eng. 2013b;135:101001–101006. doi: 10.1115/1.4024824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missirlis YF, Chong M. Aortic valve mechanics--Part I: material properties of natural porcine aortic valves. J Bioeng. 1978;2:287–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia MA, Cochran RP, Einstein DR, Rutland CJ, Kunzelman KS. A coupled fluid-structure finite element model of the aortic valve and root. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:781–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PS, Johnson SL, Evans MC, Barocas VH, Tranquillo RT. Functional tissue-engineered valves from cell-remodeled fibrin with commissural alignment of cell-produced collagen. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:83–95. doi: 10.1089/ten.a.2007.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock CA, Han L, Doehring TC. Complex collagen fiber and membrane morphologies of the whole porcine aortic valve. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah HN, Hamid MS, Stein PD. Mechanical stresses on closed cusps of porcine bioprosthetic valves: correlation with sites of calcification. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MS, Smith DB, Hiester ED. The aortic valve microstructure: effects of transvalvular pressure. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:131–141. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199807)41:1<131::aid-jbm16>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella JA, Liao J, Sacks MS. Time-dependent biaxial mechanical behavior of the aortic heart valve leaflet. J Biomech. 2007;40:3169–3177. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Sacks MS. Finite element implementation of a generalized Fung-elastic constitutive model for planar soft tissues. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2005;4:190–199. doi: 10.1007/s10237-005-0075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Sacks MS, Sellaro TL, Slaughter WS, Scott MJ. Biaxial mechanical response of bioprosthetic heart valve biomaterials to high in-plane shear. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:372–380. doi: 10.1115/1.1572518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg EJ, Mofrad MRK. Transient, three-dimensional, multiscale simulations of the human aortic valve. Cardiovasc Eng. 2007;7:140–155. doi: 10.1007/s10558-007-9038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]