Abstract

Cerebrovascular Pathologies (CVP) are the most common co-existent pathologies observed in conjunction with Alzheimer disease. CVP rarely exists in isolation in later life, and CVP most likely plays a supporting role, rather than a sole leading role, in the pathogenesis of dementia. Our goal is to illustrate CVP’s role using neuroimaging biomarkers. First, we discuss the frequency of CVP and present data from population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Here, we used a novel metric for identifying individuals with cerebrovascular imaging abnormalities (that we designate as “V+”) and present the frequency of V−/V+ in the context of absence and presence of β-amyloid elevation (designated A−/A+). Next, we discuss the contribution of CVP to neurodegeneration and use hippocampal volume loss over time in a subset of participants categorized as A−V−, A−V+, A+V−, A+V+. Lastly, we discuss the contribution of CVP to cognitive impairment and conclude with the considerations for design of future studies.

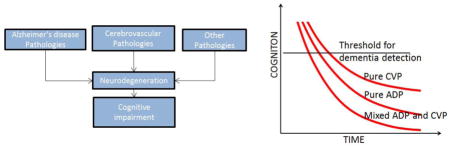

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Late onset dementia is usually a multi-factorial process wherein multiple, cumulative brain insults result in progressive cognitive impairment which ultimately leads to dementia. Cerebrovascular Pathologies (CVP) are the most common co-existent pathologies observed in conjunction with Alzheimer disease (AD)1, 2. The imaging hallmarks of CVP are white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunar infarcts, larger regional infarcts and cortical microbleeds. Both WMH and lacunar infarcts are believed to represent disease at the arteriolar level, and it is this type of CVP, that is thought to be close to, if not the main basis, for cognitive impairment in late life3, 4. WMH are not “pure” vascular lesions as they may also be related to neurodegenerative processes5, 6, but it is nearly certain that ischemic and hypoxic changes cause WMH7–10. Lacunar infarcts are “pure” vascular lesions, of course, but their relevance may also lie in the extent that they are correlated with the presence of microinfarcts11. Even if microvascular disease is not the proximate cause of cognitive dysfunction in the setting of CVP, the burden of WMH and lacunar infarcts are reasonable biomarkers to estimate the “true” causal lesion.

Our goal is to review the role of CVP when there is concomitant AD using WMH and lacunar infarcts as biomarkers for CVP. Cortical microbleeds will not be considered here because despite their possible arteriolosclerotic basis, they are related to β-amyloid abnormalities12–14. We will first discuss the frequency of CVP in the elderly, the neurodegenerative changes associated with CVP, and the cognitive changes seen due to CVP. We will discuss these in in conjunction with a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology (ADP) because understanding the interrelationship between the two is critical for placing CVP in context. We have no evidence that non-AD degenerative processes have an interaction with CVP. Hence, other pathologies (pure Lewy body disease, hippocampal sclerosis etc.) will not be discussed here. We will conclude with a discussion of typical cognitive decline trajectories seen in etiologically pure dementias and etiologically combined dementias.

Frequency of Cerebrovascular Disease

Neuropathologically, CVP becomes evident in midlife and its frequency increases with age to about 60% by age 10015. Due to the lack of consistent criteria for diagnosing cerebrovascular disease relevant to cognitive impairment at autopsy and for the clinical diagnosis of vascular dementia, the proportion of persons with dementia and cerebrovascular disease varies between 10–40%16. At autopsy, pure vascular dementia due to “silent infarcts” is often rare and most cases are temporally related to overt, clinically-evident strokes17. The overall percentage of non-demented subjects with cerebrovascular disease, defined neuropathologically, is about a third of the elderly population11, 18, 19. Imaging evidence of WMH and infarcts also supports the claim that CVP increases steadily from midlife to later life20–22.

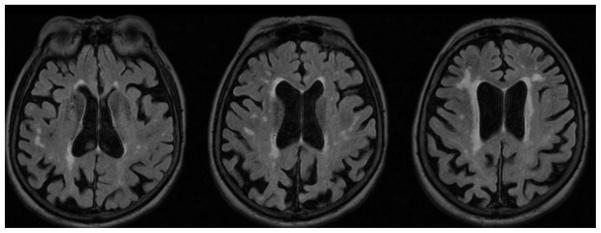

In order to understand the prevalence of CVP in the elderly before the onset of cognitive impairment, we used a population based cohort of 457 cognitively normal Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) participants (aged 70+)23. The basis for inclusion was the availability of usable Pittsburgh compound B positron emission tomography (PIB-PET) imaging from which amyloid load was ascertained and FLAIR MR imaging from which grading of WMH and enumerating of lacunar infarcts was completed24. We classified participants as being on the amyloid pathway (A+) if they had a global cortical Aβ load of ≥1.5 Standard uptake value ratio. The criteria for abnormal vascular pathway (V+) were based on a combination of infarcts and WMH burden. Either one infarct or a WMH load ≥ 1.11% of total intracranial volume was necessary for a designation of V+. We derived the WMH value using an independent subsample of 1,082 non-demented individuals (869 cognitively normal, 213 with mild cognitive impairment) from the MCSA24. We assumed that while the effect of an infarct on cognition can vary based on the size and location of the infarct, the presence of a large cortical infarct or a subcortical infarct was sufficient to indicate the presence of relevant CVP (V+). Next, we estimated how much WMH (as a percentage of total intracranial volume (TIV)) would cause the same annual rate of cognitive decline as seen by an infarct. The resultant WMH cutpoint was 1.11%. The extent of WMH/TIV% load corresponding to 1.1 is shown in Figure 1. We noted that the cutpoint for V+ resulted in assigning about one third of our population to a V+ designation. That level is about the same as estimates from the neuropathological literature for similar age non-demented cohorts25. The cutpoint value therefore reflects “some” CVP and enables us to describe the imaging correlates of CVP. We recognize that the cutpoint values are probably far below a threshold needed to produce pure vascular dementia, but the development of an algorithm to quantitate imaging evidence of CVP with WMH and infarcts to assign a CVP positivity criteria to our participants. We believe the criteria represent only a first step, and intend to refine and expand the criteria in the future.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities on a FLAIR MRI observed in an 80 year old female at the cutpoint of 1.1 % WMH of TIV. From a figure shown in24.

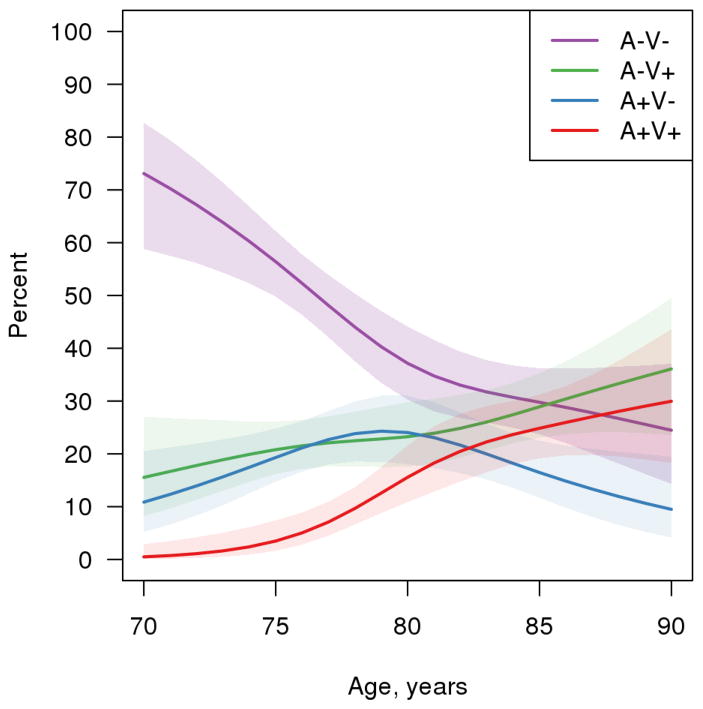

Figure 2 shows the frequency of vascular positivity and amyloid positivity in cognitively normal individuals across the age spectrum between 70 and 90 years derived from a cross-sectional analysis. The percentage with neither AVP nor CVP (A−V− group) was 73% at age 70 and dropped to 24% by age 90. Individuals with only CVP (A−V+) monotonically increased with age from 15% at age 70 to 36% at age 90. Participants with both ADP and CVP pathologies (A+V+) had an estimate of 0 at age 70 but steadily increased to 30% by age 90. Vascular-disease-positive individuals (A+V+ and A−V+) started at 15% at age 70 and steadily increased to 66% by age 90. The prevalence of participants with A+V− peaked at around age 80 and then steadily declined at higher ages. A plausible explanation was that persons who were A+V− transition to the A+V+ category. The observations of monotonic nature of vascular positivity (combined A−V+ and A+V+) and non-monotonic nature of amyloid positivity (combined A+V− and A+V+) which peaked around age 85 years but slightly decreased in the oldest old was similar to the frequency curves based on amalgamation of published neuropathological literature15. An important observation here is that there are still V+ individuals at older ages who were cognitively normal suggesting that the presence of vascular disease alone in most cases may not be sufficient to cause cognitive impairment.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Amyloid positivity (A+) and Vascular Positivity (V+) in cognitively normal elderly.

While CVP and ADP coexist in the older age ranges, similar to what has been seen in neuropathological studies1, our observations show that at younger age the overlap is less. Beyond age 90 years, however, the proportion of A+ cases who are also V+ suggests that cerebrovascular disease cannot be ignored. These data provide a population-based antemortem view of the coexistence of ADP and CVP.

Contribution of Cerebrovascular Pathologies to Neurodegeneration

CVP is associated with neurodegeneration. While extensive WMH can drive widespread cortical thinning and ventricular expansion26–28, regional WMH load may also be relevant. For example frontal WMH may have a greater impact on frontal lobe thinning28–31. On the other hand, locations of the infarctions also have a direct impact on region specific neurodegeneration32. Imaging studies show substantial white matter integrity loss (as measured by diffusion tensor imaging) in cerebrovascular disease33, 34. A recent study, for example, showed that increased vascular burden may lead to subtle attentional network dysfunction, through impaired frontal-parietal and frontal interhemispheric connectivity35.

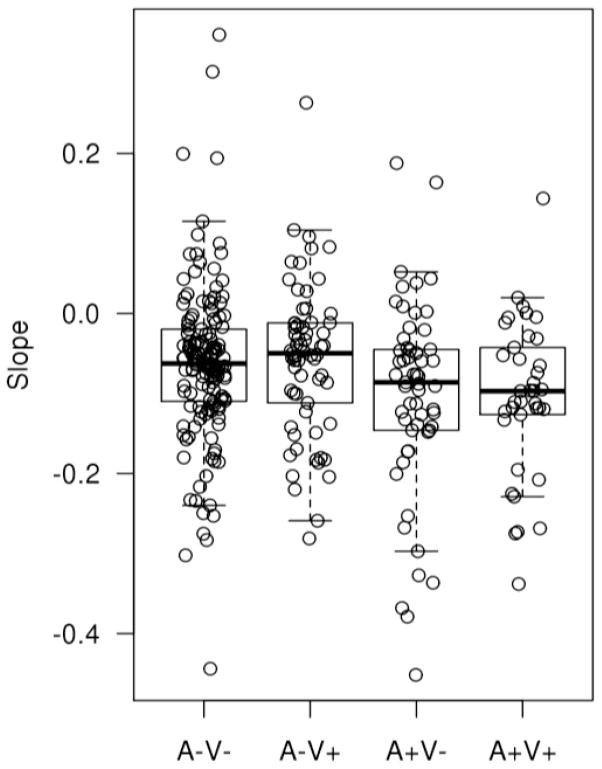

In a subset of participants from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (303 cognitively normal individuals with baseline vascular imaging ratings, PET-derived β-amyloid levels and at least two serial structural MRI scans), we gauged the impact of A+ or V+ status on hippocampal atrophy, which in turn is a direct marker of neurodegeneration. Figure 3 shows the differences in slopes of hippocampal volume by group. We found that there was significantly more hippocampal volume loss in participants due to amyloid positivity than vascular positivity. A+V− subjects had more significant volume loss than A−V− as well as A−V+ subjects (p<0.05) suggesting that the effect of ADP may be greater on hippocampal volume in comparison to the effect of CVP on hippocampal volume early in the disease process. Thus, using hippocampal volume as a proxy for neurodegeneration, V+ status did not have any impact. To the extent that hippocampal volume changes are likely to precede episodic memory loss associated with ADP, our observations fail to support a role for CVP for a cognitively relevant biomarker of neurodegeneration. On the other hand, there are many other mechanisms by which CVP could influence cognition, such as brain volume loss in other regions and disconnection of cortical regions due to white matter integrity loss36. Nonetheless, at least as far as hippocampal volume in cognitively normal persons, CVP was neither additive nor interactive with an ADP process. Our data do not support the claim that CVP interacts with ADP at the structural imaging level in the hippocampus.

Figure 3.

Slopes of Hippocampal volume on serial MR scans seen in cognitively normal individuals classified by amyloid and vascular positivity and negativity at baseline. Note that the mean values are all negative indicating some loss in all 4 groups. Subjects with A+V− and A+V+ had significantly greater decline in hippocampal volume in comparison to both the A−V− and AV+ groups.

Contribution of Cerebrovascular Pathologies to Cognitive Impairment

In the MCSA, we found that ADP and CVP both affect longitudinal cognitive trajectories adversely and are the major drivers of age related cognitive decline in the elderly24. Specifically we found that for a prototypical 79-year-old participant (the mean age in the study), the predicted annual rate of global cognitive z-score decline was −0.02 if the subject had neither CVP nor ADP (A−V−), −0.07 if the subject had CVP (A−V+), −0.08 if the subject had ADP (A+V−), and −0.13 if the subject had both CVP and ADP (A+V+). The latter is statistically the sum of the independent effect of ADP and CVP .and there was no evidence for an interaction between CVP and ADP. Other biomarker studies have also found that the effect of CVP and ADP was approximately additive on cognitive performance i.e. the effect of CVP and ADP on cognition is the sum of the independent effects of CVP and ADP37–41. Several pathology studies have also found that vascular risk factors may independently contribute to the risk of dementia by increasing the burden of CVP but do not directly influence the burden of ADP 40, 42–44.

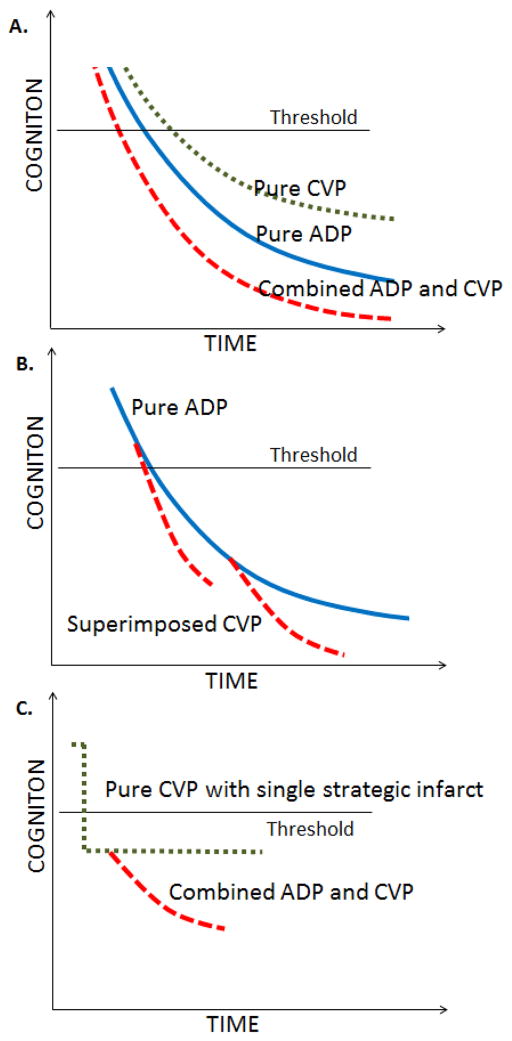

In Figure 4, we summarize the typical cognitive decline trajectories that may be expected in combined etiology dementia (A+V+) individuals in comparison to subjects with pure ADP (A+V−) and persons with pure CVP (A−V+). As illustrated in Figure 4A, for the same amount of amyloid burden and vascular burden, the time to dementia for persons with pure ADP is shorter and rate of cognitive decline is faster than those with pure CVP. The presence of both ADP and CVP significantly lowers the time to onset of dementia and increases the rate of cognitive decline in comparison to the presence of ADP or CVP alone. In Figure 4A, we made a simplistic assumption that both pathologies start almost at the same time and evolve in parallel which is rarely the case. In Figure 4B, we present a scenario where CVP may start at a later time after the onset of AD. In Figure 4C, we present a scenario where a single strategic infarct causes significant impact on cognitive performance shown by a step function followed shortly by the onset of ADP which further worsens cognition. The threshold shown in the figure indicates the cognition threshold for dementia detection.

Figure 4.

Typical cognitive decline trajectories that may be expected in pure vs. multi-etiology dementias as a function of time. Panel A illustrates trajectories when the evolution of CVP and ADP are nearly at the same time. Panel B illustrates trajectories when CVP starts at a later time after the onset of ADP. Panel C illustrates trajectory where the event of a single strategic infarct (pure CVP) is followed shortly by the onset of ADP. The threshold shown in the figure indicates the cognitive threshold for dementia detection.

Design of Future Studies

It is important to account for cerebrovascular disease while studying other dementing diseases because it has an impact on the expression of cognitive impairment. Intervention trials on different dementia populations may lend different results due to the difference in vascular disease burden. We recognize that including cerebrovascular imaging will make presentations that focus on Alzheimer’s or Lewy Body diseases more complicated, but burden of CVP should be accounted for.

Studies need to be better designed to accommodate and understand multi-etiology dementias because they represent at least a substantial minority of dementia cases and perhaps a majority over age 90 years. Multicenter studies such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative exclude participants with severe vascular disease which might limit the generalizability of some studies from that cohort, especially ones that make claims about cerebrovascular lesions.

In AD, the latest diagnostic formulations (NIA-AA and International Working Group criteria) have proposed the incorporation of AD-related biomarker based cutoffs for diagnosis45, 46. The field is rapidly moving towards the use of cut-points for operationalization of biomarker-based clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia. While there is an impetus to standardize criteria for clinical diagnosis, pathological diagnosis, and neuroimaging image interpretation and reporting in vascular cognitive impairment.47, 48, there are still no widely accepted criteria for determining biomarker positivity for cerebrovascular disease. Given multiple different hallmarks of CVP based on neuroimaging, there is a need to develop methodologies, such as we described here, that provide a consolidated measure for cerebrovascular disease and thus allow us to classify subjects as positive or negative for CVP. Our attempt described here and in a prior publication24 is a preliminary one that requires further refinement and validation. This will not only accelerate our understanding of CVP in the context of late life dementia but also provide a single metric that can be used to account for CVP while studying other neurodegenerative and age-related illnesses.

Highlights.

We used a novel metric for identifying individuals with CVD imaging abnormalities.

We estimated prevalence of CVD and amyloid in a cognitively normal elderly sample.

Greater hippocampal volume loss due to amyloid elevation than vascular abnormalities.

Faster rate of cognitive decline in individuals with both amyloid and CVD abnormalities than alone.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Heather Wiste and Scott Przybelski for the Statistical analysis. This work was supported by NIH grants R00 AG37573, R01 AG11378, R01 AG041851, R01 AG03467, P50 AG16574/P1, U01 AG06786; the Gerald and Henrietta Rauenhorst Foundation grant

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures

Dr. Vemuri receives research support from the NIH. Dr. Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study; is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by TauRX Pharmaceuticals, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; and receives research support from the NIH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes L, Boyle P, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community versus clinic cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:691–701. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jellinger KA. Understanding the pathology of vascular cognitive impairment. J Neurol Sci. 2005;229–230:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith EE, Schneider JA, Wardlaw JM, Greenberg SM. Cerebral microinfarcts: the invisible lesions. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:272–282. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erten-Lyons D, Woltjer R, Kaye J, et al. Neuropathologic basis of white matter hyperintensity accumulation with advanced age. Neurology. 2013;81:977–983. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihara M, Polvikoski TM, Hall R, et al. Quantification of myelin loss in frontal lobe white matter in vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:579–589. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0635-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas AJ, Perry R, Barber R, Kalaria RN, O’Brien JT. Pathologies and pathological mechanisms for white matter hyperintensities in depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:333–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas AJ, O’Brien JT, Barber R, McMeekin W, Perry R. A neuropathological study of periventricular white matter hyperintensities in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;76:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray ME, Vemuri P, Preboske GM, et al. A quantitative postmortem MRI design sensitive to white matter hyperintensity differences and their relationship with underlying pathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:1113–1122. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318277387e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouw AA, Seewann A, Vrenken H, et al. Heterogeneity of white matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer’s disease: post-mortem quantitative MRI and neuropathology. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2008;131:3286–3298. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longstreth WT, Jr, Sonnen JA, Koepsell TD, Kukull WA, Larson EB, Montine TJ. Associations between microinfarcts and other macroscopic vascular findings on neuropathologic examination in 2 databases. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:291–294. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318199fc7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poels MM, Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: an update of the Rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2010;41:S103–106. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benito-Leon J, Romero JP, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F. Faster cognitive decline in elders without dementia and decreased risk of cancer mortality: NEDICES Study. Neurology. 2014;82:1441–1448. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schilling S, DeStefano AL, Sachdev PS, et al. APOE genotype and MRI markers of cerebrovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2013;81:292–300. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfda4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson PT, Head E, Schmitt FA, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is not “brain aging”: neuropathological, genetic, and epidemiological human studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:571–587. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0826-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jellinger KA, Attems J. Is there pure vascular dementia in old age? J Neurol Sci. 2010;299:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopman DS, Rocca WA, Cha RH, Edland SD, Kokmen E. Survival study of vascular dementia in Rochester, Minnesota. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:85–90. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Steinhorn SC, et al. AD lesions and infarcts in demented and non-demented Japanese-American men. Annals of neurology. 2005;57:98–103. doi: 10.1002/ana.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Cochran EJ, et al. Relation of cerebral infarctions to dementia and cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. 2003;60:1082–1088. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055863.87435.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knopman DS, Penman AD, Catellier DJ, et al. Vascular risk factors and longitudinal changes on brain MRI: the ARIC study. Neurology. 2011;76:1879–1885. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d753f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longstreth WT, Jr, Dulberg C, Manolio TA, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of brain infarcts defined by serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2002;33:2376–2382. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032241.58727.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longstreth WT, Jr, Arnold AM, Beauchamp NJ, Jr, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of worsening white matter on serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2005;36:56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149625.99732.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, et al. Vascular and amyloid pathologies are independent predictors of cognitive decline in normal elderly. Brain. 2015;138:761–771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thong JY, Hilal S, Wang Y, et al. Association of silent lacunar infarct with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1219–1225. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knopman DS, Griswold ME, Lirette ST, et al. Vascular imaging abnormalities and cognition: mediation by cortical volume in nondemented individuals: atherosclerosis risk in communities-neurocognitive study. Stroke. 2015;46:433–440. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang JW, Kim S, Na HY, et al. Effect of white matter hyperintensity on medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. 2013;69:229–235. doi: 10.1159/000345999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolandzadeh N, Liu-Ambrose T, Aizenstein H, et al. Pathways linking regional hyperintensities in the brain and slower gait. Neuroimage. 2014;99:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo SW, Lee JM, Im K, et al. Cortical thinning related to periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tullberg M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C, et al. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology. 2004;63:246–253. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000130530.55104.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saczynski JS, Sigurdsson S, Jonsdottir MK, et al. Cerebral infarcts and cognitive performance: importance of location and number of infarcts. Stroke. 2009;40:677–682. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.530212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chao LL, Decarli C, Kriger S, et al. Associations between white matter hyperintensities and beta amyloid on integrity of projection, association, and limbic fiber tracts measured with diffusion tensor MRI. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maillard P, Carmichael OT, Reed B, Mungas D, DeCarli C. Cooccurrence of vascular risk factors and late-life white-matter integrity changes. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1670–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lockhart SN, Luck SJ, Geng J, et al. White matter hyperintensities among older adults are associated with futile increase in frontal activation and functional connectivity during spatial search. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence AJ, Patel B, Morris RG, et al. Mechanisms of cognitive impairment in cerebral small vessel disease: multimodal MRI results from the St George’s cognition and neuroimaging in stroke (SCANS) study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchant NL, Reed BR, DeCarli CS, et al. Cerebrovascular disease, beta-amyloid, and cognition in aging. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:1006, e1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lo RY, Jagust WJ. Vascular burden and Alzheimer disease pathologic progression. Neurology. 2012;79:1349–1355. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826c1b9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Launer LJ, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Markesbery W, White LR. AD brain pathology: vascular origins? Results from the HAAS autopsy study. Neurobiology of aging. 2008;29:1587–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Launer LJ, Hughes TM, White LR. Microinfarcts, brain atrophy, and cognitive function: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study Autopsy Study. Annals of neurology. 2011;70:774–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosano C, Aizenstein HJ, Wu M, et al. Focal atrophy and cerebrovascular disease increase dementia risk among cognitively normal older adults. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahtiluoto S, Polvikoski T, Peltonen M, et al. Diabetes, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia: a population-based neuropathologic study. Neurology. 2010;75:1195–1202. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d7f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, et al. Diabetes is related to cerebral infarction but not to AD pathology in older persons. Neurology. 2006;67:1960–1965. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247053.45483.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort: neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1136–1146. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c5efb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jack CR, Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]