Many psychiatric disorders are comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD). Individuals with any mood or anxiety disorder are twice as likely to develop SUD compared to healthy individuals (1). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is no exception, with PTSD patients four times more likely to develop SUD than those without PTSD (2). However, despite numerous clinical reports of increased drug use in PTSD and other mood disorders, preclinical studies have struggled to replicate these effects in rodents.

In this issue of Biological Psychiatry, Enman and colleagues (3) investigated anhedonia-like symptoms and cocaine self-administration in an animal model of PTSD. Rats were exposed to single prolonged stress (SPS), a putative animal model for PTSD, or handling as control, and assessed one week later for sucrose preference, spontaneous locomotor activity, conditioned place preference for cocaine, cocaine self-administration, and dopamine receptor density within the striatum. In support of the face validity of SPS as an animal model of PTSD, the authors found SPS resulted in reduced sucrose preference and reduced locomotor activity during the dark cycle, which seem to model clinical reports of anhedonia in PTSD patients. Although evidence for dopaminergic disturbances in patients with PTSD has only limited support, Enman et al. also found decreased dopamine and D2 receptor binding in the striatum, and increased dopamine transporter density in the caudal nucleus accumbens. Detracting from the face validity of SPS, however, they also found that their model resulted in reduced cocaine conditioned place preference and no difference from controls in cocaine self-administration during acquisition or under extended access conditions, which appears at odds with clinical observations of increased comorbidity between PTSD and SUD.

Enman and colleagues are not alone in their inability to replicate comorbidity with SUD and anxiety and mood disorders in rodents, particularly those disorders whose symptoms include anhedonia. One argument is that, unlike humans, rodents do not self-medicate to alleviate anhedonia with increased levels of drug use. However, a more likely explanation for these discrepant findings is the tendency to ignore the time course and individual differences when attempting to model comorbid psychiatric diseases.

Time course of PTSD development

PTSD is a serious, debilitating, often lifelong disorder that can only be clinically diagnosed more than one month after trauma exposure. Epidemiological reports have shown that most individuals adapt to a severe stressor or trauma within 1 to 4 weeks (4), and rodent studies have paralleled this observation (5). However, despite this evidence and diagnostic requirement for substantial temporal separation from trauma to PTSD manifestation, many preclinical researchers do not wait an adequate amount of time from stress exposure to behavioral tests assessing for PTSD-like symptoms. Although the one week isolation period in the Enman et al. (3) study was informative, face and translational validity would be improved, and perhaps the results would be different, with a more disease-relevant spacing from stress exposure to behavioral and neurochemical evaluation.

Individual differences in PTSD development

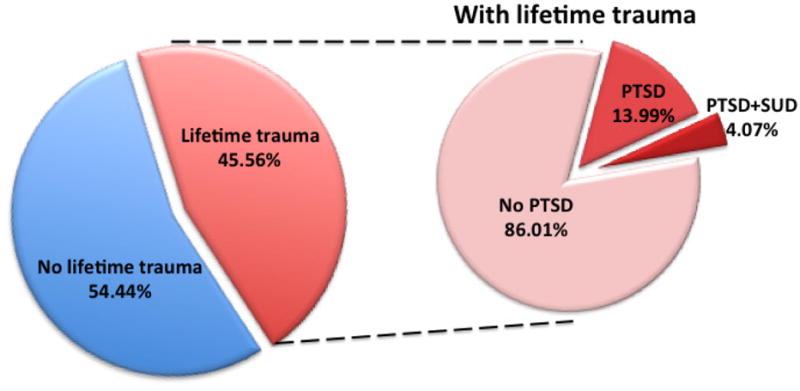

In order to model clinical PTSD, it is imperative to consider the importance of individual differences in response to trauma exposure. In the National Comorbidity Survey, Kessler and colleagues (2) reported epidemiological findings in a national, non-institutional cross-sectional sample. As shown in Figure 1, adapted from (2), an estimated 45.56% of individuals are exposed to one or more traumatic events in their lifetime. However, of individuals exposed to trauma, only an estimated 13.99% later develop PTSD. The fact that only a proportion of stress-exposed individuals later develop a maladaptive phenotype is far too often disregarded in preclinical studies, which more often than not probe the stressed group as a homogeneous group for PTSD-like symptoms. While there is a general focus on whether an animal model results in disease-relevant symptomatology for face and translational validity, if an animal model does not capture similar proportions of disease-relevant symptoms it does not meet the burdens necessary for face, translational, and predictive validity.

Figure 1.

Adapted from the National Comorbidity Survey findings reported in (2)

Although Enman et al. (3) did not investigate individual differences in their SPS model of PTSD, a beautifully designed study by Toledano and Gisquet-Verrier (6) demonstrated that SPS can indeed engender phenotypes of susceptible and resilient rats long after stress exposure. In this study, rats were first tested for baseline anxiety-like and novelty reactivity behavior, after which the rats were exposed to SPS or control handling. To adequately model the time course of PTSD development, the authors then waited 30 days before testing for anxiety- and PTSD-like symptoms in a battery of behavioral tests. Rats were classified as ‘susceptible’ if their observed behavior was greater than 1 standard deviation from the mean of the control group in 3 indices—yielding a proportion of 37.5% ‘susceptible’ and 62.5% ‘resilient’ rats. Others have found similar proportions of susceptible/resilient rodents 30 or more days following trauma exposure in different PTSD animal models, reviewed in (5), emphasizing the importance of both time course and individual differences.

Individual differences in SUD comorbidity

The issue of individual differences in susceptibility/resiliency to PTSD following trauma becomes even more important when investigating comorbidity between disorders, as an even smaller population is at risk for developing both disorders. As shown in Figure 1, of those individuals who develop PTSD, only 29.10% will also exhibit comorbid SUD. Kessler et al. (2) report that the incidence of SUD is four times higher in those with PTSD than those without PTSD. Therefore, this comorbidity of PTSD and SUD is certainly a substantial concern, but the increased rate of SUD would only occur in approximately 4% of individuals exposed to severe stress or trauma.

Given these epidemiological findings, in studies that do not account for individual differences it should be no surprise that evidence for comorbid SUD and PTSD is limited. In the study from Enman and colleagues (3), evidence for neither increased cocaine conditioned place preference nor self-administration was reported. With less than 10 rats per experiment exposed to SPS (only 5 for extended access cocaine self-administration), any effects of SPS-susceptible rats would be masked by the lack of effect in the SPS-resilient rats, composing at least 60% of the SPS group (6).

This issue is not unique to investigations of increased drug preference and self-administration in animal models of PTSD, but in fact plagues research in the fields of other mood disorders as well. SUD incidence is also substantially increased in major depressive disorder (MDD) (1), yet many researchers, including our own laboratory, have struggled to replicate this effect in rodents. For example, we have previously demonstrated that chronic social defeat stress, an animal model that elicits some symptoms relevant to MDD, results in attenuated as opposed to escalated cocaine self-administration in male rats (7), seemingly discrepant with clinical observations of increased rates of cocaine abuse within depressed patients.

However, an interesting study by Krishnan and colleagues (8) demonstrated that even an inbred strain of C57bl/6 mice show distinct individual differences in susceptibility/resilience to chronic social defeat stress. After ten days of sub-threshold chronic social defeat stress, mice could be separated into two discrete groups, ‘susceptible’ or ‘resilient’, based upon their responses in an array of behavioral and physiological tests, most notably social interaction. When separated in this manner, only the susceptible mice showed increased cocaine conditioned place preference.

Similarly, we have recently reported individual differences in anhedonic-like responses following chronic social defeat stress in female rats (9). Female rats were characterized as either ‘stress-vulnerable’ or ‘stress-resistant’ based upon saccharin preference during chronic social defeat, and only one subgroup showed increased cocaine self-administration during a 24 h “binge”, as well as suppressed cocaine-induced extracellular dopamine efflux in the nucleus accumbens shell.

Conclusion Remarks

In conclusion, both time course and individual differences are essential considerations when studying stress-related disorders. Throughout life, we are all exposed to stress, from relatively minor stress to severe stress and trauma. However, only a subset of susceptible individuals goes on to develop a maladaptive psychiatric disorder such as PTSD or MDD, and within these susceptible individuals an even smaller subset develops comorbidity with SUD or other mood disorders. Furthermore, the effects of stress within these vulnerable individuals are observed long after stress exposure. Similar patterns of individual differences are observed in other psychiatric disorders, including SUD (10). It is imperative to consider this when developing and implementing animal models to capture a human condition—we cannot study all animals that undergo stress in the same manner; even in inbred strains, individual animals may be more or less susceptible to experimental manipulations. Rather than this being viewed as a limitation or impediment to preclinical research, it must be viewed as a desirable goal, and not disregarded as variability within a single stress-exposed group.

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgement: NIDA grant 5R01-DA031734 to KAM

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enman NM, Arthur K, Ward SJ, Perrine SA, Unterwald EM. Anhedonia, Reduced Cocaine Reward, and Dopamine Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foa EB, Stein DJ, McFarlane AC. Symptomatology and psychopathology of mental health problems after disaster. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 2):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen H, Matar MA, Zohar J. Maintaining the clinical relevance of animal models in translational studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. ILAR journal / National Research Council, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. 2014;55:233–245. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilu006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toledano D, Gisquet-Verrier P. Only susceptible rats exposed to a model of PTSD exhibit reactivity to trauma-related cues and other symptoms: an effect abolished by a single amphetamine injection. Behav Brain Res. 2014;272:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miczek KA, Nikulina EM, Shimamoto A, Covington HE., 3rd Escalated or suppressed cocaine reward, tegmental BDNF, and accumbal dopamine caused by episodic versus continuous social stress in rats. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9848–9857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0637-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimamoto A, Holly EN, Boyson CO, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Individual differences in anhedonic and accumbal dopamine responses to chronic social stress and their link to cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:825–834. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3725-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245:1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]