Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate acceptance of sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening and measure STI prevalence in an asymptomatic adolescent ED population.

Study design

This was a prospectively enrolled cross-sectional study of 14–21 year old patients who sought care at an urban pediatric ED with non-STI related complaints. Participants completed a computer-assisted questionnaire to collect demographic and behavioral data and were asked to provide a urine sample to screen for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. We calculated STI screening acceptance and STI prevalence. We used logistic regression to identify factors associated with screening acceptance and presence of infection.

Results

Of 553 enrolled patients, 326 (59.0%) agreed to be screened for STIs. STI screening acceptability was associated with having public health insurance (aOR 1.7; 1.1, 2.5) and being sexually active (sexually active but denying high risk activity [aOR 1.7; 1.1, 2.5]; sexually active and reporting high risk activity [aOR 2.6; 1.5, 4.6]). Sixteen patients (4.9%; 95% CI 2.6, 7.3) had an asymptomatic STI. High-risk sexual behavior (aOR 7.2; 1.4, 37.7) and preferential use of the ED rather than primary care for acute medical needs (aOR 4.0; 1.3, 12.3) were associated with STI.

Conclusions

STI screening is acceptable to adolescents in the ED, especially among those who declare sexual experience. Overall, there was a low prevalence of asymptomatic STI. Risk of STI was higher among youth engaging in high-risk sexual behavior and those relying on the ED for acute health care access. Targeted screening interventions may be more efficient than universal screening for STI detection in the ED.

Adolescents have the highest rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) of any age group and comprise 9 million of the 19 million new cases of STIs each year.(1) Many STIs are asymptomatic and may result in significant morbidity, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, increased susceptibility to HIV, and infertility.(2) For these reasons, the Healthy People 2020 objectives identify as a national priority addressing the STI epidemic with a specific focus on STI reduction in adolescents.(3) The American Academy of Pediatrics(4) (AAP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(2) (CDC), and the US Preventative Services Task Force(5) (USPTF) all recommend at least annual STI screening among sexually active females. The AAP(4) and CDC(2) also recommend at least annual STI screening for sexually active males in settings with high prevalence rates. Despite these recommendations, the majority of adolescents have never been screened for STIs.(6)

Poor access to primary care may be an important factor;(7–9) more than one-third of adolescents cannot identify a source of primary care.(10–13) Emergency departments (EDs) are a key point of access to care for many adolescents, as they account for almost 15 million ED visits annually.(14–17) Because the ED often serves as a safety-net for high risk and vulnerable populations, the ED may provide a strategic venue for asymptomatic STI screening. Although the CDC recommends universal screening for HIV in EDs nationally,(18) there are no current recommendations for STI screening in EDs. Therefore, the goal of this study was to evaluate the acceptability of STI screening and measure the prevalence of asymptomatic STI in a population of adolescents seeking care in an urban pediatric ED.

Methods

We performed a prospective, cross-sectional study between December 2013 and July 2014, enrolling a convenience sample of adolescents who presented to the Children’s National Health System ED in Washington, DC, with non-STI-related chief complaints. The hospital is a freestanding, urban, tertiary care, pediatric academic center located in a city with the highest rates of STIs nationally(19) and with annual ED visits of approximately 90,000. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital.

Males and females aged 14–21 years were eligible for study participation. Because informed consent was required, we excluded patients who were critically ill, were developmentally delayed, presented with altered mental status, were in police custody, or were non-English speaking. We also excluded patients if they presented after an acute sexual assault or with a chief complaint that was potentially related to an STI. Exclusionary chief complaints included lower abdominal pain, dysuria, vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, anogenital lesions and/or pain for females; dysuria, anogenital lesions and penile pain or discharge for males. Additionally, we excluded patients presenting specifically for STI testing or treatment. Participants were identified as eligible for participation after being triaged and after discussion of inclusion and exclusion criteria with the clinical team. Patients were then confidentially approached by research staff, asked to participate, and if they agreed, asked to provide informed consent. Because adolescents are allowed to consent for sexual health services in our state, a waiver of parental consent was granted by our IRB.

Enrolled patients completed a validated computer-assisted survey through LimeSurvey software (LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool, version 2; Hamburg, Germany) with survey items including questions about sexual experience, history of STIs and prior testing, and demographic information. Participants were also asked to provide a confidential phone number for follow-up of positive results. Participants who agreed to STI screening were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae using urine-based polymerase chain reaction (Abbott RealTime PCR; Illinois, USA). All positive results were reported to the patient and treatment was coordinated by the principal investigator. Patients were contacted again within 2 weeks after result notification to determine whether they received treatment as prescribed.

Statistical analyses

The primary objectives of this study were to determine the acceptability of urine-based STI screening and to calculate the prevalence of STIs in a population of asymptomatic adolescents seen in an urban pediatric ED. We also measured the association of calculated STI screening acceptability and STI prevalence with reported sexual risk behaviors. Subpopulations included patients who reported being sexually experienced and those who reported high risk sexual behavior. We defined high risk sexual behavior as lack of condom use during last sexual intercourse and/or identification of >1 sexual partner in the last 3 months.(2) We calculated the prevalence of positive C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae tests with 95% confidence intervals. Our secondary objectives included identifying factors associated with acceptance of STI screening as well as factors associated with presence of an STI. Based on prior data, correlates of interest included age, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and sexual behavior.(20) We also sought to evaluate whether identification of a primary care provider (PCP) or preferential use of the ED versus primary care or health clinic for acute medical needs were associated with STI screening acceptance and STI.(12) We performed bivariable logistic regression to identify associations between demographic and behavioral data and STI screening acceptability as well as STI outcomes. Covariates with p-values <0.2 in bivariable logistic regression were included in our multivariable logistic regression models. To account for patients who declined STI screening in calculation of STI prevalence, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we assumed that all patients who declined STI screening would have tested negative for N gonorrhoeae/CT if screened.

Results

A total of 553 adolescents were enrolled in this study. The study sample was composed of largely non-Hispanic black patients insured via public health insurance, and who identified a PCP. Approximately half of the study population reported being sexually experienced, and almost 20% disclosed high risk sexual behaviors. (Table I).

Table 1.

Selected Demographics of Study Population

| Demographic | Entire Study Population (n=553) | Agreed to STI Screening (n=326) | Declined STI Screening (n=227) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 16.1 (1.8) | 16.4 (1.8) | 15.8 (1.6) | <0.001 | |

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 290 (52.4) | 162 (49.7) | 128 (56.4) | 0.12 |

| Male | 263 (47.6) | 164 (50.3) | 99 (43.6) | ||

| Racial/Ethnic Group, n (%) | Non-Hispanic White | 40 (7.3) | 21 (6.5) | 19 (8.5) | 0.66 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 376 (68.9) | 220 (68.3) | 156 (69.6) | ||

| Hispanic | 81 (14.8) | 49 (15.2) | 32 (14.3) | ||

| Other | 49 (9.0) | 32 (9.9) | 17 (7.6) | ||

| Insurance Status | Private | 158 (28.6) | 77 (23.6) | 81 (35.7) | 0.001 |

| Governmental | 375 (67.8) | 241 (73.9) | 134 (59.0) | ||

| Uninsured | 20 (3.6) | 8 (2.5) | 12 (5.3) | ||

| Primary Care Provider Identification | 480 (88.2) | 280 (87.2) | 200 (89.7) | 0.38 | |

| Preferential Use of ED When Sick | 128 (23.2) | 83 (25.5) | 45 (19.8) | 0.12 | |

| Sexual Experience | Denied Sexual Activity | 289 (52.3%) | 142 (43.6%) | 147 (64.8%) | <0.001 |

| Sexually Active, Denied High Risk Activity | 164 (29.7%) | 107 (32.8%) | 57 (25.1%) | ||

| High Risk Sexual Activity | 100 (18.1%) | 77 (23.6%) | 23 (10.1%) | ||

P-values are reported as comparison between participants who agreed to STI screening and those who declined using chi2 testing.

STI Screening Acceptability

Of the 553 adolescents enrolled, 326 (59.0%, 95% CI 54.8%, 63.1%) agreed to be screened for STIs. Adolescents who agreed to STI screening were significantly older (16.4 years vs. 15.8 years; p<0.001) and were less likely to have private insurance (23.6% vs. 35.7%; p=0.002). There were no differences in gender, race/ethnicity, PCP identification, or reported preferential use of the ED for acute medical needs between those who agreed and those who declined urine STI screening.

Patients who were sexually active were more likely to accept STI screening than those who denied sexual activity (69.7% vs. 49.1%, p<0.001) (Table I). In a multivariable model that included age, gender, insurance status, preferential use of the ED when sick, and sexual experience, factors associated with STI testing included governmental insurance and sexual experience (Table II).

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Acceptance of STI Testing

| Factor | AOR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 14–16 | Referent |

| 17–21 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | |

| Male Gender | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | |

| Insurance status | Private | Referent |

| Governmental | 1.7 (1.1, 2.5) | |

| Uninsured | 0.6 (0.2, 1.7) | |

| Preferential Use of the ED When Sick | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | |

| Sexual Experience | Denied Sexual Activity | Referent |

| Sexually Active, Denied High Risk Activity | 1.7 (1.1, 2.5) | |

| High Risk Sexual Activity | 2.6 (1.5, 4.6) | |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio

Of the 227 patients who declined STI testing, the reasons for refusal included: sexual inexperience (64.8%, n=147), not perceiving themselves to be at risk for an STI (10.1%, n=23), STI tested within the past year (5.3%, n=12%), and prefer not to provide a reason (19.8%, n=45). No patients declined STI testing due to confidentiality concerns. Of the 80 sexually active patients who declined STI screening, the most common reasons for refusal were that they were not currently sexually active (17.5%), did not perceive themselves to be at risk (46.3%), recently were tested (21.3%), other (8.8%), or preferred not to provide a reason (6.3%).

Asymptomatic STI Prevalence

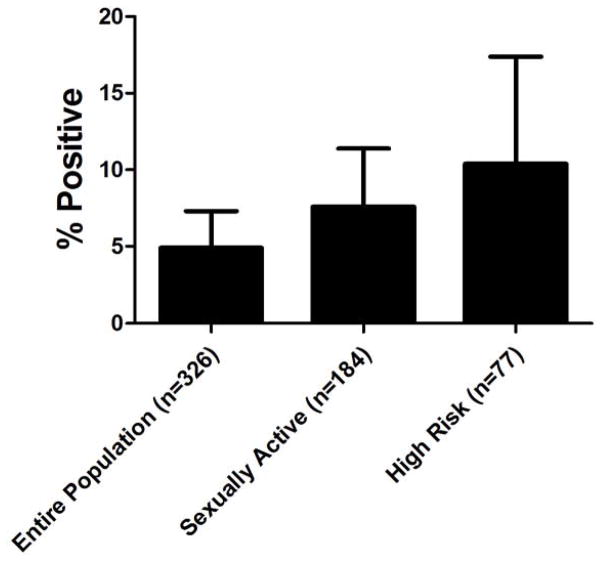

Sixteen (4.9%; 95% CI 2.6, 7.3) of the 326 patients who underwent STI screening had an asymptomatic STI (15 with C trachomatis alone, and one with C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae). The risk of STI was associated with sexual experience. The Figure describes STI prevalence by sexual risk. Two patients who denied being sexually experienced tested positive for an STI; one who later stated that she was sexually active during follow up and another who tested negative when retested by her primary care provider. Patients who reported being sexually active were more likely to have an asymptomatic STI than those who denied prior sexual experience (OR 5.8; 95% CI 1.3, 25.8). The risk of an STI was higher among adolescents reporting high-risk sexual behavior (OR 8.1; 95% CI 1.7; 39.2) compared with those who denied sexual activity. The presence of an STI was not associated with age (p=0.09), gender (p=0.3), race/ethnicity (p=0.7), insurance status (p=0.6), identification of a PCP (p=0.1). STI was associated with preferential use of the ED for acute medical needs (62.5% vs. 21.9%; p=0.002).

Figure.

STI Prevalence by Sexual Behavior

Nearly half (43.8%; n=7) of patients with an STI had been tested within the last 6 months, and 71.4% of these tests had been negative. Furthermore, almost one-fifth (18.8%) of patients with an STI had never been tested previously. One-half of infections were diagnosed among patients who “definitely did not” think they had an STI, and no patients with an STI thought he or she had an STI.

In the multivariable model that included age, PCP identification, preferential use of the ED, and sexual experience, engaging in high risk sexual activity (aOR 7.2; 95% CI 1.4, 37.7) and preferential use of the ED (aOR 4.0; 95% CI 1.3, 12.3) were associated with the presence of an STI. (Table III)

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Presence of STI

| Demographic | AOR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age Category | 14–16 years | Referent |

| 17–21 years | 0.9 (0.3, 2.8) | |

| Primary Care Provider Identification | 0.7 (0.2, 2.5) | |

| Preferential Use of ED When Sick | 4.0 (1.3, 12.3) | |

| Sexual Experience | Denied Sexual Activity | Referent |

| Sexually Active, Denied High Risk Activity | 3.4 (0.6, 18.6) | |

| High Risk Sexual Activity | 7.2 (1.4, 37.7) | |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to calculate STI prevalence under the assumption that all patients who declined STI screening would have tested negative for STI if they had been tested (16/553). In this scenario, the calculated STI prevalence was 3.0% (95% 1.8, 4.9).

Discussion

We found that 60% of adolescents in an urban pediatric ED agreed to be screened for asymptomatic STI. In this population, we detected STIs in approximately 5% of asymptomatic patients. STI screening acceptance was associated with being sexually experienced, older age, and being publicly insured. Rates of infection increased with sexual experience and among those reporting engagement in high risk sexual behaviors. In addition to sexual behaviors, preference for seeking acute medical care in the ED rather than with a primary care provider also was associated with STI. These results suggest potential areas for targeted screening.

Although there are a few prior studies that have evaluated adolescent STI prevalence in EDs,(20–22) this study offered screening to patients regardless of reported sexual activity and included an asymptomatic population solely. We chose these selection criteria to more precisely estimate the prevalence of STI in a cohort of patients who would be approached for screening if a universal STI screening protocol were instituted. Inclusion of a symptomatic population is not the role of a screening program because screening tests are applied to an asymptomatic population, whereas diagnostic testing is used when an individual is suspected of having a disease or illness.(23)

Our STI screening protocol was designed to mimic the HIV universal screening recommendations by the CDC (ie, screening regardless of sexual activity).(18) Similar to a previous study of HIV screening,(24, 25) we found that sexual inexperience and recent testing elsewhere were common reasons for refusal of STI screening. Furthermore, although the reduction of undiagnosed HIV infection through more broad-based screening efforts is a critical public health need, recent data suggests that non-targeted opt-out screening may not significantly increase the number of newly diagnosed HIV infection compared with targeted opt-in HIV screening.(26)

Overall, our study demonstrates a low prevalence of infection in an unselected population of asymptomatic adolescent patients in the ED. Our detected prevalence is similar to prevalence of N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis infections found in other studies that did not select populations based on sexual activity, although these studies did not exclude symptomatic patients.(21, 22) However, rates of STI were associated with greater engagement in high risk sexual behavior and preferential use of the ED versus primary care, suggesting that a targeted screening strategy may offer the best balance between efficiency and benefit to patients.

One-half of our participants identified with an STI reported prior STI testing within the last 6 months. This is concerning because current recommendations for STI screening by the CDC, USPSTF, and AAP recommend annual screening. (4–6) If these patients were screened only annually, the patients found to be positive in our study may have gone undetected for several months, increasing the risk of both infection-related morbidity and further spread of infection to others. Additionally, almost one-third of those infected had never previously undergone STI screening, further supporting ED-based STI screening programs. Furthermore, our data reveal that adolescents with STIs may not perceive themselves at risk for an STI because > 50% of patients diagnosed with an STI “definitely did not” think they had an STI, and not one patient with an STI thought he or she may be infected. This observation supports the establishment of STI screening in the ED because youth with an STI may not necessarily request STI testing unless prompted.

As expected, sexual behavior was associated with acceptance of STI screening as well as presence of an STI. Our multivariable model revealed that it was not just being sexually active that was associated with STI screening acceptance and infection, but in fact, engaging in high risk sexual behavior. The odds of STI screening acceptance and STI presence were higher among patients engaging in sexual activity and highest among those reporting high-risk sexual behavior. No participants provided confidentiality concerns as a reason for STI screening refusal. This may be because the ED might be viewed as a location providing more anonymity than a long-standing pediatrician or a local community clinic, further supporting STI screening efforts in the ED.

Preference for seeking care in the ED compared with a primary care office or a health clinic also was associated with STI. This finding is consistent with data that demonstrate adolescents with high risk behaviors are more likely to utilize the ED for care.(12, 27, 28) Although these studies have identified that adolescents who frequently utilize the ED report higher rates of substance use, dating violence, and mental health problems, we additionally identified an association of STIs and preferential use of the ED for care.

The findings from this work should be considered in light of several potential limitations. We used a convenience sampling strategy; patients were approached only when research staff were available. However, our research assistants staff the ED 7 days per week from 7am to 11pm, minimizing the risk of missed patients. Furthermore, because information regarding sexual experience and history of prior STIs and testing was obtained through survey, the data may be prone to social desirability and recall bias. There are data demonstrating discrepancies between positive STI status and self-reported sexual behavior.(29) However, adolescents are more likely to share sensitive health information through computerized surveys than through face-to-face interviews.(30, 31) Finally, this study was conducted at a single, urban pediatric ED located in a community with high incident STI infections, and the findings may not be generalizable to patients cared for in other ED settings. However, the health disparities faced by youth in the community served by our ED suggest that this target for intervention is justified.

Targeted screening interventions that focus on patients at increased risk may be a more efficient strategy to improve the diagnosis of asymptomatic STIs in the ED.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD070910 [to M.G] and the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Institutional Pilot Award UL1TR000075 [to M.G.]).

List of Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ED

Emergency Department

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Interval

- OR

Odds Ratio

- STIs

Sexually transmitted infections

- USPTF

US Preventative Services Task Force

Footnotes

Reprint Request Author: Monika Goyal

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports/Centers for Disease Control. 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cydulka RK, Rhodes KV, Lettman NA, Almeida SL, et al. Tobacco control interventions in the emergency department: a joint statement of emergency medicine organizations. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:e417–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Screening for nonviral sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e302–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Preventive Services Task Force. [Accessed March 12, 2013];Screening for Chlamydial Infection, Topic Page. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspschlm.htm.

- 6.Hoover KW, Leichliter JS, Torrone EA, Loosier PS, Gift TL, Tao G. Chlamydia screening among females aged 15–21 years--multiple data sources, United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl 2):80–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rand CM, Shone LP, Albertin C, Auinger P, Klein JD, Szilagyi PG. National health care visit patterns of adolescents: implications for delivery of new adolescent vaccines. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2007;161:252–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein JD, McNulty M, Flatau CN. Adolescents’ access to care: teenagers’ self-reported use of services and perceived access to confidential care. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1998;152:676–82. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.7.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Foregone health care among adolescents. JAMA. 1999;282:2227–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grove DD, Lazebnik R, Petrack EM. Urban emergency department utilization by adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:479–83. doi: 10.1177/000992280003900806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann CU, Barr J, Kelly PJ. Emergency department utilization by adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15:485–90. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90496-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:361–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodwell DA, Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1993 summary. Adv Data. 1995:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Tayyib AA, Miller WC, Rogers SM, Leone PA, Gesink Law DC, Ford CA, et al. Health care access and follow-up of chlamydial and gonococcal infections identified in an emergency department. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:583–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181666ab7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCaig LF, Nawar EW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2006 Jun 23;(372):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park MJ, Paul Mulye T, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin CE., Jr The health status of young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:305–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;101:987–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 12, 2014];2014 http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats13/tables/2.htm.

- 20.Goyal M, Hayes K, Mollen C. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence in symptomatic adolescent emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:1277–80. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller MK, Dowd MD, Harrison CJ, Mollen CJ, Selvarangan R, Humiston SG. Prevalence of 3 sexually transmitted infections in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:107–12. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uppal A, Chou KJ. Screening adolescents for sexually transmitted infections in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:20–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streiner DL. Diagnosing tests: using and misusing diagnostic and screening tests. J Pers Assess. 2003;81:209–19. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8103_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minniear TD, Gilmore B, Arnold SR, Flynn PM, Knapp KM, Gaur AH. Implementation of and barriers to routine HIV screening for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1076–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, Silverman M, Byyny RL, Eisert S, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA. 2010;304:284–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein PW, Messer LC, Myers ER, Weber DJ, Leone PA, Miller WC. Impact of a routine, opt-out HIV testing program on HIV testing and case detection in North Carolina sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41:395–402. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh V, Walton MA, Whiteside LK, Stoddard S, Epstein-Ngo Q, Chermack ST, et al. Dating violence among male and female youth seeking emergency department care. Annals of emergency medicine. 2014;64:405–12. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham RM, Ranney M, Newton M, Woodhull W, Zimmerman M, Walton MA. Characteristics of youth seeking emergency care for assault injuries. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e96–105. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiClemente RJ, Sales JM, Danner F, Crosby RA. Association between sexually transmitted diseases and young adults’ self-reported abstinence. Pediatrics. 2011;127:208–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paperny DM, Aono JY, Lehman RM, Hammar SL, Risser J. Computer-assisted detection and intervention in adolescent high-risk health behaviors. J Pediatr. 1990;116:456–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–73. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]