Abstract

Objectives

Type 2 endoleaks are common after endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) but their clinical significance remains undefined and their management controversial. We determined risk factors for type 2 endoleak and associations with adverse outcomes.

Methods

We identified all EVAR patients in the Vascular Study Group of New England abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) database. Patients were subdivided into two groups: 1) those with no endoleak or transient type 2 endoleak and 2) persistent type 2 endoleak or new type 2 endoleak (no endoleak at completion of case). Patients with other endoleak types and follow-up shorter than 6 months were excluded. Multivariable analysis was used to evaluate predictors of persistent or new type 2 endoleaks. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analysis were used to evaluate predictors of reintervention and survival.

Results

2367 EVAR patients had information on endoleaks; 1977 (84%) were in group 1, of which 79% had no endoleak at all and 21% were transient endoleaks that resolved at follow-up. The other 390 (16%) were in group 2, of which 31% had a persistent leak and 69% had a new leak at follow-up that was not seen at the time of surgery. Group 2 was older (mean age 75 vs. 73 years, P<.001), and less likely to have COPD (24% vs. 34%, P<.001) or elevated creatinine levels (2.6% vs. 5.3%, P=0.027). Coil embolization of one or both hypogastric arteries was associated with a higher rate of persistent type 2 endoleaks (12 vs. 8%, P=0.024), as was distal graft extension (12% vs. 8%, P=0.008). In multivariable analysis, COPD (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5–0.9, P=0.017) was protective against persistent type 2 endoleak, while hypogastric artery coil embolization (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0–2.2, P=0.044), distal graft extension (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.3, P=0.025) and age ≥ 80 (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4–5.3, P=0.004) were predictive. Graft type was also associated with endoleak development. Persistent type 2 endoleaks were predictive of post-discharge reintervention (OR 15.3, 95% CI 9.7–24.3, P<.001), however not predictive of long-term survival (OR 1.1, 95%CI 0.9–1.6, P=0.477).

Conclusion

Persistent type 2 endoleak is associated with hypogastric artery coil embolization, distal graft extension, older age, the absence of COPD, and graft type, but not with aneurysm size. Persistent type 2 endoleaks are associated with an increased risk of reinterventions, but not rupture or survival. This reinforces the need for continued surveillance of patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks and the importance of follow-up to detect new type 2 endoleaks over time.

INTRODUCTION

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) is associated with significantly higher short-term survival rates when compared to open AAA repair, but equivalent long-term survival rates.1–5 Though EVAR imparts an early survival benefit, this benefit is not sustained and EVAR is associated with more aneurysm-related reinterventions than open repair.6 Endoleaks are the most common complication of EVAR and are a frequent indication for reintervention. While Type 1 and Type 3 endoleaks necessitate reintervention and repair, the clinical significance of type 2 endoleaks remains controversial.

Most type 2 endoleaks resolve spontaneously and the one-year post-operative prevalence ranges from 1–10%.7–9 However, there is evidence that persistent type 2 endoleaks are associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes (sac enlargement, aneurysm rupture, need for reintervention, conversion to open repair).9, 10 Results from the EUROSTAR registry suggest that type 2 endoleaks are associated with aneurysmal growth and reintervention, but not with rupture or conversion to open repair.10 A study of 832 EVAR patients found persistent type 2 endoleaks accounting for 38% of secondary reinterventions.11 Other studies have shown no such relationships between type 2 endoleaks and adverse outcomes,12, 13 but these studies may have been insufficiently powered.

Current recommendations suggest intervention for type 2 endoleaks in the presence of aneurysmal growth and/or endoleak persistence; however the exact criteria for reintervention remain undefined.7, 8, 14 Some physicians argue for aggressive management, such as prophylacticembolization of patent vessels communicating with the endoleak at the time of graft implantation, while others endorse conservative monitoring approaches.9, 15, 16 Nevertheless, prophylactic embolization has mixed success in preventing type 2 endoleaks.17, 18

Our goal was to study the incidence of type 2 endoleaks, both transient and persistent, and to assess adverse outcomes, including post-operative complications and reinterventions. In addition, we wished to identify independent predictors of persistent and delayed type 2 endoleaks, and to determine whether persistent type 2 endoleaks were associated with late reinterventions and survival.

METHODS

We undertook a retrospective analysis of the Vascular Surgery Group of New England (VSGNE) database, which is a multidisciplinary quality improvement collaborative between both academic and non-academic hospitals. More detailed information can be found at www.vascularweb.org/regionalgroups/vsgne/pages/home.aspx. This study contained de-identified data only without any protected health information and is therefore not subject to patient consent or Institutional Review Board approval. We used data from January 2003 through December 2014 and identified all patients undergoing EVAR. The presence or absence of an endoleak was recorded by the surgeon at the time of case completion as well as at each follow-up. Patients were subdivided into two categories: 1) those who either had no endoleak at any time or those with a transient type 2 endoleak (defined as an endoleak at completion of the case that was not seen again at any point during follow-up) and 2) persistent type 2 endoleaks (defined as an endoleak at completion of case that was also detected at follow-up) or those who developed a new type 2 endoleak (defined as no endoleak at completion of the case that developed an endoleak at any point postoperatively). Because the ability to detect a type 2 endoleak at the time of graft implantation is depends on several factors (contrast dose, timing of angiography, body habitus, quality of imaging equipment, and how carefully one examines the completion angiogram) which could not be quantified in this study, we felt patients with a “new” type 2 endoleak should be grouped with those with persistent type 2 endoleaks. Patients who underwent reinterventions for a type 2 endoleak were grouped into the latter category. Patients who developed Type 1 or Type 3 endoleaks at any time, or those without endoleak information were excluded from the analysis. Patients with a follow-up time shorter than 6 months were also excluded from our analysis. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of inclusion- and exclusion criteria for this study.

We analyzed potential predictors of persistent type 2 endoleak including baseline demographics and comorbidities and operative factors including hypogastric artery coverage, both intentional (planned prior to procedure to treat distal aneurysm extent) and unintentional (inadvertent extension of graft not necessary to treat distal aneurysm extent). In addition, both preoperative and intraoperative hypogastric artery coiling were analyzed. Presence of an iliac aneurysm was defined by an iliac diameter > 1.5cm, using the maximum diameter of either the common or internal iliac artery. We also evaluated the influence of graft type on persistent type 2 endoleak, but limited this to only those grafts with at least 100 implants.

Outcomes at long-term follow-up were also documented. These included the development of sac growth, migration, limb occlusion, aneurysm-related symptoms, and rupture. Reintervention rates for these aforementioned indications were recorded, as were rates of conversion to open repair.

Patient demographics, comorbidities, perioperative details, and outcomes are reported as proportions of the total. We compared categorical variables between outcome subgroups using the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. The means of continuous variables were compared using student’s t-test. Multivariable logistic regression using purposeful selection19 was used to determine independent predictors of type 2 endoleak development. Reintervention rates and survival were compared between the two subgroups using Kaplan-Meier analysis, survival curves were compared using the log-rank test, and multivariable predictors of reintervention and survival were identified using Cox regression modeling. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

At the time of analysis, 2,367 patients in the VSGNE undergoing EVAR had information on endoleaks at both the end of the procedure as well as long-term follow-up, which on average was 463 days. Group 1 included 1977 patients (84% of the total) with no or transient endoleak. Of these, 1560 (79%) had no endoleaks and 417 (21%) were transient endoleaks that had resolved spontaneously at follow-up. Group 2 consisted of 390 patients (16% of the total); of these, 120 (31%) had a persistent leak and 270 (69%) developed a new leak that was not seen at the time of surgery (Figure 1). There were 36 patients undergoing an intervention for type 2 endoleak. The baseline demographics and comorbidities of patients in groups 1 and 2 are shown in Table I. Patients in group 2 were older, less likely to have had high creatinine levels (>1.8) preoperatively, and less likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or a history of smoking.

Table I.

Comparison of baseline characteristics and comorbidities between patients with no/transient type 2 endoleaks vs. patients with persistent/new type 2 endoleaks.

| No/Transient Type II Endoleak |

Persistent/New Type II Endoleak |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=1977 | N=390 | P-value | |

| Age (mean in yrs ± SD) | 73± 8.1 | 75±8.1 | <.001 |

| Male | 82% | 79% | 0.157 |

| White race | 97% | 97% | 0.876 |

| Smoking history | 87% | 80% | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 85% | 82% | 0.078 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 19% | 19% | 0.947 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 33% | 32% | 0.479 |

| CABG/PCI | 30% | 28% | 0.264 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 8.4% | 9.2% | 0.613 |

| COPD | 34% | 24% | <.001 |

| Dialysis-dependent | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.538 |

| Creatinine, >1.8 mg/dL | 5.3% | 2.6% | 0.027 |

| Preoperative Medication | |||

| Aspirin | 74% | 70% | 0.087 |

| Statin | 71% | 69% | 0.344 |

| Plavix | 7.4% | 7.7% | 0.862 |

CABG/PCI, coronary artery bypass graft/percutaneous coronary intervention; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

Anatomic Characteristics and Surgical History

Across all anatomical measured characteristics, no significant differences were found between the two groups (Table II). The mean aneurysm diameter was similar for both groups and there was no difference in iliac aneurysm involvement. Aortic rupture and prior aortic surgery did not differ across groups.

Table II.

Aortic surgical history and anatomic characteristics.

| No/Transient Type II Endoleak |

Persistent/New Type II Endoleak |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=1977 | N=390 | p-value | |

| Aneurysm Diameter (mean, mm ± SD) | 57.0±24.2 | 57.7±11.1 | 0.615 |

| Iliac Aneurysm | 0.412 | ||

| None | 77% | 76% | |

| Unilateral | 13% | 11% | |

| Bilateral | 11% | 13% | |

| Prior Aortic Surgery | 0.775 | ||

| None | 98% | 98% | |

| AAA | 1.1% | 0.5% | |

| SAAA | 0.2% | 0.3% | |

| Bypass | 0.3% | 0.5% | |

| Other | 0.8% | 0.5% | |

| EVAR | 0.2% | 0.0% | |

| Rupture | 2.4% | 2.8% | 0.605 |

AAA, infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair; SAAA, suprarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Intraoperative Details

Procedural details are shown in Table III. While coverage of the hypogastric artery and graft configuration (AUI vs. bifurcated) had no association with persistent type 2 endoleaks, hypogastric coil embolization was associated with more persistent type 2 endoleaks (12% vs. 8%, P=0.024). Of the 390 patients in group 2, 12% had a graft extension during surgery, while only 8% of those in group 1 had an extension (P=0.008). Table IV shows proportions of type 2 endoleak development at the procedure and at follow-up per graft type.

Table III.

Intraoperative details.

| No/Transient Type 2 Endoleak |

Persistent/New Type 2 Endoleak |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1977) % |

(N=390) % |

P-value | |

| Graft Configuration | 0.755 | ||

| Aorto-bi-iliac | 94.0% | 94.9% | |

| Aorto-uni-iliac | 4.7% | 3.8% | |

| Aorto-aortic | 1.3% | 1.3% | |

| Hypogastric Artery Coiling | 8.3% | 12.0% | 0.024 |

| Hypogastric Artery Coverage | 12.4% | 14.4% | 0.287 |

| Graft Extension | 7.7% | 12.0% | 0.008 |

Hypogastric artery coiling and graft extension data were missing for 183 patients

Table IV.

Development of persistent or new type 2 endoleaks at procedure and at follow-up by graft type.

| Type II Endoleak at procedure | Type II Endoleak at Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | total | % | N | total | % | |

| AneurRx | 86 | 257 | 33.5% | 27 | 257 | 10.5% |

| Endurant | 61 | 194 | 31.4% | 17 | 194 | 8.8% |

| Excluder Low-Permeability | 175 | 747 | 23.4% | 167 | 747 | 22.4% |

| Powerlink | 60 | 289 | 20.8% | 23 | 289 | 8.0% |

| Talent | 61 | 147 | 41.5% | 8 | 147 | 5.4% |

| Zenith | 124 | 537 | 23.1% | 76 | 537 | 14.2% |

Grafts with fewer than 100 implants were not included in this analysis (Ancure, Excluder Original, MEGS/VI, Cordis, Aorfix, Zenith Low Profile, AFX, Endurant II, Zenith Flex, Other)

Complications and Reinterventions

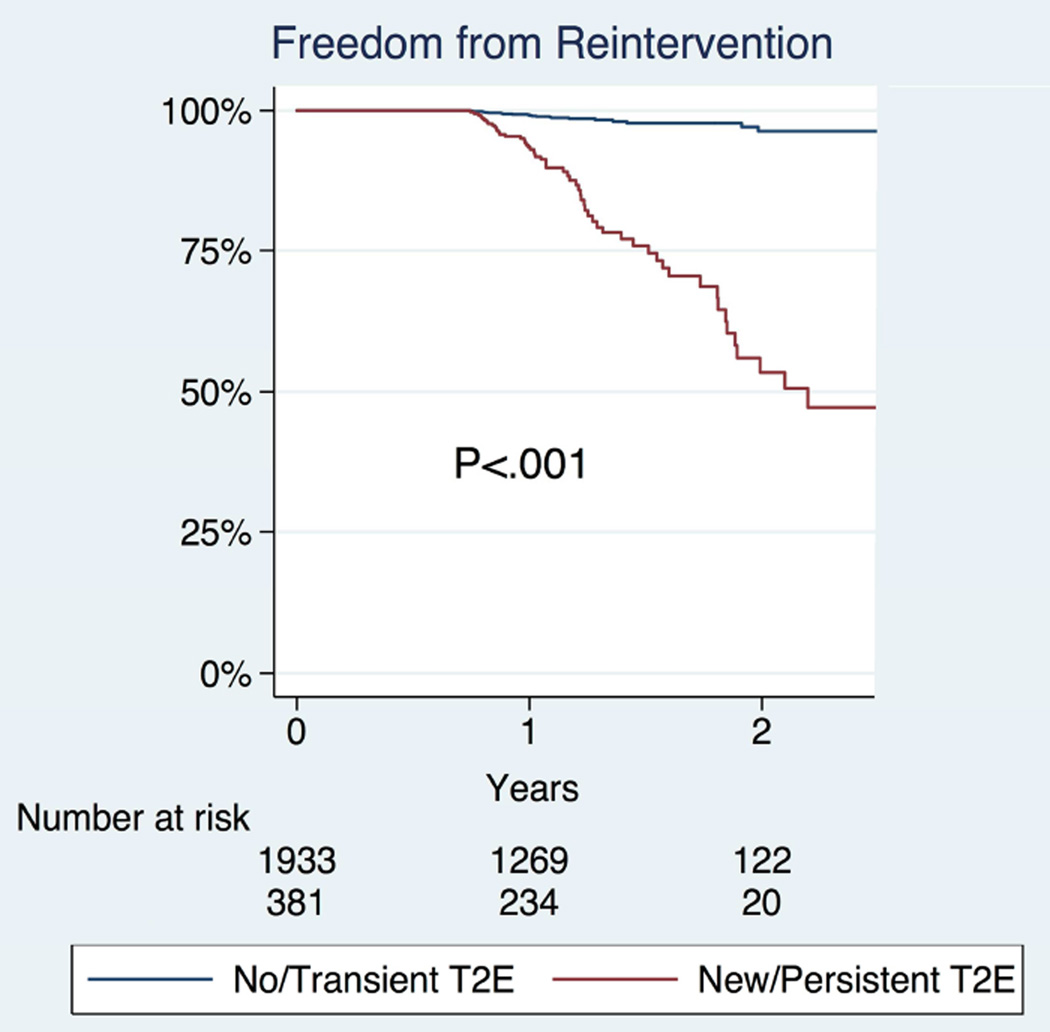

At follow-up, data on sac growth were available for 104 patients, where 46% of patients with a persistent/new type 2 endoleak and 6% of patients with no/ transient type 2 endoleak had sac growth (P<.001). (Table V) Conversion to open repair was more common in patients with a persistent or new type 2 endoleak (0.8% vs. 0.2%, P=0.024). For the 2,330 patients with available follow-up data on any reintervention, those with persistent type 2 endoleaks were more likely to undergo reinterventions (18.6% vs. 1.5%), which was significant by Kaplan Meier (P<.001) (Figure 2). All patients who developed sac growth underwent reintervention. Among patients for whom long-term data were available regarding graft migration or symptoms/rupture there were no significant differences in the rates of these complications. Survival of patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks did not differ from those with no/transient type 2 endoleaks (Figure 3). Among patients with persistent or new type 2 endoleak, there was no difference in long-term survival in those with and without re-intervention (HR 0.8, 95% CI 0.3–1.8, P=0.547).

Table V.

Complications and reinterventions at Follow-up.

| Data Available For |

No/Transient Type 2 Endoleak |

Persistent/New Type 2 Endoleak |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | % | ||

| Any Reintervention | 2,330 | 1.5% | 18.6% | <.001 |

| Conversion to Open Repair | 2,298 | 0.2% | 0.8% | 0.024 |

| Sac Growth | 104 | 5.9% | 45.7% | <.001 |

| Graft Migration | 103 | 11.4% | 2.9% | 0.082 |

| Symptoms or Rupture | 101 | 0.0% | 4.5% | 0.210 |

Figure 2.

Freedom from reinterventions among patients with no/transient type 2 endoleaks vs. patients with persistent/new type 2 endoleaks

Figure 3.

Survival of patients with no/transient type 2 endoleaks vs. patients with persistent/new type 2 endoleaks.

Multivariable Predictors

Multivariable predictors of persistent type 2 endoleaks were hypogastric artery coil embolization, distal graft extension, and age 80 or older, while COPD was protective. After accounting for these characteristics, the Powerlink (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.9, P=0.012) and Endurant (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.9, P=0.026) (which are both no longer available) were protective of persistent or new type 2 endoleaks, while the Excluder with its lower permeability fabric was predictive of persistent or new type 2 endoleaks (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.0, P=0.011). (Table VI) Persistent type 2 endoleaks were predictive of post-discharge reinterventions (OR 15.3, 95% CI 9.7–24.3, P<.001), however not predictive of mortality (Table VII). Predictors of mortality were COPD, older age, creatinine level >1.8 mg/dL, and discharge to an institutional facility. There was insufficient power to determine independent predictors of conversion to open repair.

Table VI.

Multivariable predictors of persistent/new type 2 endoleaks.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <60 | - | - | - | |

| 60–69 | 1.5 | 0.7–2.9 | 0.271 | |

| 70–79 | 1.7 | 0.9–3.3 | 0.119 | |

| ≥ 80 | 2.7 | 1.4–5.3 | 0.004 | |

| History of Smoking | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.076 | |

| COPD | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.017 | |

| Preop ASA | 0.8 | 0.6–1.1 | 0.202 | |

| Hypertension | 0.8 | 0.6–1.0 | 0.093 | |

| Creatinine, >1.8 mg/dL | 0.5 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.059 | |

| Hypogastric coiling (preop or intraop) | 1.5 | 1.0–2.2 | 0.044 | |

| Graft extension | 1.6 | 1.1–2.3 | 0.025 | |

| Graftype | ||||

| AneuRx | 0.8 | 0.5–1.3 | 0.357 | |

| Endurant | 0.5 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.026 | |

| Excluder Low Permeability | 1.5 | 1.1–2.0 | 0.011 | |

| Powerlink (Intuitrak) | 0.5 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.012 | |

| Talent | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 | 0.119 | |

| Zenith | ref | ref | ref | |

Table VII.

Multivariable predictors of reintervention and survival

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of Post-discharge Reintervention | |||

| Female | 1.0 | 0.6–1.8 | 0.899 |

| Smoking History | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 | 0.814 |

| Creatinine, >1.8 mg/dL | 0.6 | 0.2–2.5 | 0.454 |

| COPD | 1.2 | 0.8–2.0 | 0.394 |

| Persistent/New Type 2 Endoleak | 15.3 | 9.7–24.3 | <.001 |

| Predictors of Mortality | |||

| Age, years | |||

| <60 | - | - | - |

| 60–69 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.2 | 0.424 |

| 70–79 | 2.5 | 1.1–5.4 | 0.025 |

| ≥ 80 | 3.4 | 1.5–7.5 | 0.003 |

| Female | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | 0.551 |

| Not Home Discharge | 1.6 | 1.0–2.4 | 0.032 |

| CHF | 1.4 | 1.0–2.1 | 0.078 |

| COPD | 1.6 | 1.2–2.1 | <.001 |

| Creatinine, >1.8 mg/dL | 1.7 | 1.1–2.8 | 0.031 |

| Persistent/New Type 2 Endoleak | 1.1 | 0.9–1.6 | 0.477 |

DISCUSSION

In this large study of 2367 patients who underwent EVAR, we found that persistent type 2 endoleaks are associated with hypogastric coil embolization, distal graft extension, the absence of COPD, age 80 and older, and graft type. Patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks are more likely to have sac expansion and to undergo reintervention during follow-up.

The EUROSTAR registry showed that coil embolization of side branches increased the risk of type 2 endoleak. They showed that blocking one or two hypogastric arteries was predictive on univariate analysis, but not on multivariable analysis.10 In addition, Conrad et al. found an increased risk for secondary intervention in patients who had coil embolization of any vessel, but did not find an association of hypogastric embolization with persistent type 2 endoleaks.11 The results from our study provide a possible connection between these two prior findings, suggesting that the increased risk of reintervention, seen in patients with coil embolization, may stem from an increased risk of developing persistent type 2 endoleaks. A possible explanation for the increased risk of developing persistent type 2 endoleaks among patients who receive hypogastric artery coiling is that these patients likely have more extensive aneurysms that extend into the common iliac arteries. Although the presence of iliac aneurysms showed no correlation with persistent type 2 endoleaks, some iliac aneurysms might have a sufficient distal neck that does not require extension into the external iliac artery. Increased blood flow through lumbar arteries and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) may be enhanced to provide flow to the pelvis, thus contributing to persistent lumbar and IMA type 2 endoleaks. Coverage without coiling likely preserves some hypogastric branches that would otherwise be lost with embolization, which may reduce the need for enhanced flow from lumbar and IMA branches. In contrast, intraoperative coverage of the hypogastric arteries, whether intentional or not, was not associated with persistent type 2 endoleak development.

In our analyses the Powerlink and Endurant stent grafts had lower rates of new or persistent type 2 endoleaks. The Endurant stent graft however is no longer available and was enhanced in 2013 into the Endurant II with a lower profile, additional limb lengths and an aorto-uni-iliac option. The number of patients treated with the Endurant II in our study was too small to draw any conclusions. The Powerlink is also no longer available in the US as it was replaced by the AFX device. Powerlink has a longer main body and external billowing fabric that should occupy more space thereby potentially decreasing type 2 endoleaks. However, the Zenith graft, which also has a longer main body was not associated with as low a rate of type 2 endoleak. The low-permeability Excluder was predictive of type 2 endoleaks. The original Excluder was associated with sac expansion despite an absence of radiographic endoleak, which led to an introduction of a new graft with lower permeability in 2004. This stent graft initially had the lowest profile for years and may have allowed an increase in treatment of those with peripheral arterial disease and women, which may have an impact on development of type 2 endoleak, but we are unable to analyze this further.

Our study demonstrates that the development of persistent type 2 endoleaks correlates with an increase in sac growth at follow up. This is consistent with a previous report, which found sac enlargement in 54.5% of patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks during their median follow-up period of 28.7 months.9 In our analyses, 46% of patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks had sac growth. Along with the risk of sac growth, we found that patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks were more likely to undergo a reintervention. Buth et al. also found an increased risk for intervention and aneurysmal growth, without a change in rupture risk or survival.20 Jones et al. showed similar findings, but their results also revealed an increased risk of aneurysm rupture, which our study did not confirm.9 Our analysis includes data with a 1-year mean follow-up period, and thus limits our ability to assess the risk of late rupture. The overall increased risk of reintervention reinforces the need for continued surveillance of patients with persistent type 2 endoleaks and if necessary, intervening for sac expansion.

Our study revealed no relationship between aneurysm size and persistent type 2 endoleaks. This is consistent with some earlier studies,9, 10 while other reports have demonstrated that the risk of developing type 2 endoleaks is increased with larger aneurysm diameter.21, 22 Aneurysm sac diameter was also found in one study to be an independent predictor of secondary reintervention.11 Our results, however, do not demonstrate this associated risk when accounting for persistent type 2 endoleak. Others have noted an association of persistent type 2 endoleak with and an increasing numbers of patent aortic branches.21, 22 However, these data are not collected in the VSGNE dataset.

Another significant predictor of type 2 endoleaks in our analysis is increased patient age, which is consistent with previous studies.10, 21 Van Marrewjik et al. similarly showed that patients with persistent endoleaks were two years older than patients without endoleaks.10 An explanation for this trend has yet to be proposed. Also, gender did not affect the incidence of persistent type 2 endoleak in our analyses.23 Recent work by Dubois et al. also demonstrated this and showed that the incidence of endoleaks did not vary significantly across gender, despite differences in anatomic characteristics of aneurysms.24

Earlier studies have reported an association between COPD and spontaneous resolution of type 2 endoleaks,21 which is confirmed in our study. This phenomenon may be explained by an increased blood viscosity in COPD leading to increased thrombus formation or atherosclerosis in vessels.10, 21 We also demonstrated on univariate analysis that smoking was associated with a lower rate of persistent type 2 endoleak, which has been seen in previous studies.10, 20, 25 However, as smoking is the primary risk factor for COPD, these two variables may be perfectly collinear and in our study smoking was no longer significant after accoutnting for COPD in multivariable analysis.

To limit the number of reinterventions that occur post-EVAR, further research is needed to explain the association between aneurysms that require hypogastric branch coiling and an increased risk of persistent type 2 endoleak.

Although our study has a large number of patients from multiple institutions, an important caveat is that it is not a randomized controlled trial. One important limitation is that one-year follow-up is not available for a significant percentage of patients in the database. Long-term follow-up in VSGNE is required at one year, accepting anything after nine months. Entry of longer follow-up data is suggested but not required. In this analysis, true one-year follow-up (≥ 365 days) was 74%. It is possible that entry of further longer-term data is associated with re-interventions. Therefore, analysis of data beyond this time point may overestimate adverse events.

Furthermore, because the variable within the VSGNE is recorded as symptoms and/or rupture, we are unable to distinguish patients who developed symptoms from those who ruptured. This study is also limited by our lack of information on all potentially relevant anatomy, e.g. thrombus burden and patency of side branches. Importantly, long-term follow-up data for several outcome variables are limited (e.g. sac growth, graft migration, conversion to open, and rupture). For example, only 101 patients had data collected on whether they developed symptoms and/or rupture. Also limited are the specifics concerning what postoperative surveillance schedules and imaging modalities were used and what types of reinterventions were performed when undertaken. It is also possible that there is reporting bias, in that those performing re-intervention or noting sac growth may be more likely to carefully inspect for and document the presence of a type 2 endoleak. However, to our knowledge, our study represents the largest American series and may be broadly generalizable due to both academic and community hospitals that the VSGNE incorporates.

CONCLUSION

Type II endoleaks that persist or develop during follow-up are associated with future sac growth and reintervention. Persistent type 2 endoleaks are predicted by coil embolization of hypogastric arteries, distal graft extension, older age, the absence of COPD, and graft type; allowing heightened awareness in those patients at increased risk. Future analysis with longer follow-up and more thoroughly documented outcome data on contemporarygrafts will improve our understanding of persistent type 2 endoleak.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 5R01HL105453-03 from the NHLBI and the NIH T32 Harvard-Longwood

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the SCVS 41st Annual Symposium on March 16, 2013 in Miami, FL.

References

- 1.Prinssen M, Verhoeven EL, Buth J, Cuypers PW, van Sambeek MR, Balm R, et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1607–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lederle FA, Freischlag JA, Kyriakides TC, Padberg FT, Jr, Matsumura JS, Kohler TR, et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomized trial. Jama. 2009;302(14):1535–1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankensteijn JD, de Jong SE, Prinssen M, van der Ham AC, Buth J, van Sterkenburg SM, et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(23):2398–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenhalgh RM, Brown LC, Powell JT, Thompson SG, Epstein D, Sculpher MJ. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(20):1863–1871. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bruin JL, Baas AF, Buth J, Prinssen M, Verhoeven EL, Cuypers PW, et al. Long-term outcome of open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(20):1881–1889. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederle FA, Freischlag JA, Kyriakides TC, Matsumura JS, Padberg FT, Jr, Kohler TR, et al. Long-term comparison of endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1988–1997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverberg D, Baril DT, Ellozy SH, Carroccio A, Greyrose SE, Lookstein RA, et al. An 8-year experience with type II endoleaks: natural history suggests selective intervention is a safe approach. Journal of vascular surgery. 2006;44(3):453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinmetz E, Rubin BG, Sanchez LA, Choi ET, Geraghty PJ, Baty J, et al. Type II endoleak after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a conservative approach with selective intervention is safe and cost-effective. Journal of vascular surgery. 2004;39(2):306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones JE, Atkins MD, Brewster DC, Chung TK, Kwolek CJ, LaMuraglia GM, et al. Persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with adverse late outcomes. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007;46(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Marrewijk CJ, Fransen G, Laheij RJ, Harris PL, Buth J. Is a type II endoleak after EVAR a harbinger of risk? Causes and outcome of open conversion and aneurysm rupture during follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27(2):128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad MF, Adams AB, Guest JM, Paruchuri V, Brewster DC, LaMuraglia GM, et al. Secondary intervention after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):383–389. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b365bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timaran CH, Ohki T, Rhee SJ, Veith FJ, Gargiulo NJ, 3rd, Toriumi H, et al. Predicting aneurysm enlargement in patients with persistent type II endoleaks. Journal of vascular surgery. 2004;39(6):1157–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuerff SN, Rockman CB, Lamparello PJ, Adelman MA, Jacobowitz GR, Gagne PJ, et al. Are type II (branch vessel) endoleaks really benign? Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16(1):50–54. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee SJ, Ohki T, Veith FJ, Kurvers H. Current status of management of type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17(3):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10016-003-0002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum RA, Carpenter JP, Stavropoulous SW, Fairman RM. Diagnosis and management of type 2 endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;4(4):222–226. doi: 10.1016/s1089-2516(01)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin BG, Marine L, Parodi JC. An algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of type II endoleaks and endotension after endovascular aneurysm repair. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2005;17(2):167–172. doi: 10.1177/153100350501700222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould DA, McWilliams R, Edwards RD, Martin J, White D, Joekes E, et al. Aortic side branch embolization before endovascular aneurysm repair: incidence of type II endoleak. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(3):337–341. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelrod DJ, Lookstein RA, Guller J, Nowakowski FS, Ellozy S, Carroccio A, et al. Inferior mesenteric artery embolization before endovascular aneurysm repair: technique and initial results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15(11):1263–1267. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141342.42484.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buth J, Harris PL, van Marrewijk C, Fransen G. The significance and management of different types of endoleaks. Semin Vasc Surg. 2003;16(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7967(03)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abularrage CJ, Crawford RS, Conrad MF, Lee H, Kwolek CJ, Brewster DC, et al. Preoperative variables predict persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brountzos E, Karagiannis G, Panagiotou I, Tzavara C, Efstathopoulos E, Kelekis N. Risk factors for the development of persistent type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012;18(3):307–313. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.4646-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouriel K, Greenberg RK, Clair DG, O'Hara PJ, Srivastava SD, Lyden SP, et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair: gender-specific results. Journal of vascular surgery. 2003;38(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubois L, Novick TV, Harris JR, Derose G, Forbes TL. Outcomes after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair are equivalent between genders despite anatomic differences in women. Journal of vascular surgery. 2013;57(2):382 e1–389 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koole D, Moll FL, Buth J, Hobo R, Zandvoort H, Pasterkamp G, et al. The influence of smoking on endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(6):1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]