Abstract

Context

Latinos are the largest and fastest-growing ethnically diverse group in the U.S.; they are also the most overweight. Mexico is now second to the U.S. in experiencing the worst epidemic of obesity in the world. Objectives of this study were to (1) conduct a systematic review of obesity-related interventions targeting Latinos living in the U.S. and Latin America and (2) develop evidence-based recommendations to inform culturally relevant strategies targeting obesity.

Evidence acquisition

Obesity-related interventions, published between 1965 and 2010, were identified through searches of major electronic databases in 2010–2011. Selection criteria included evaluation of obesity-related measures; intervention conducted in a community setting; and at least 50.0% Latino/Latin American participants, or with stratified results by race/ethnicity.

Evidence synthesis

Body of evidence was based on the number of available studies, study design, execution, and effect size. Of 19,758 articles, 105 interventions met final inclusion criteria. Interventions promoting physical activity and/or healthy eating had strong or sufficient evidence for recommending (1) school-based interventions in the U.S. and Latin America; (2) interventions for overweight or obese children in the healthcare context in Latin America; (3) individual-based interventions for overweight or obese adults in the U.S.; (4) individual-based interventions for adults in Latin America; and (5) healthcare-based interventions for overweight or obese adults in Latin America.

Conclusions

Most intervention approaches combined physical activity and healthy eating to address both sides of the energy-balance equation. Results can help guide comprehensive evidence-based efforts to tackle the obesity epidemic in the U.S. and Latin America.

Context

For 3 decades, the worldwide obesity epidemic has continued to gain momentum.1 The U.S. has led in the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Populations of low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) historically evidenced fewer noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors, suffering instead from communicable diseases and other “diseases of poverty.” Nevertheless, LMICs are experiencing accelerated nutrition-related and epidemiologic transitions linked to higher rates of NCDs.2,3 Close to 80% of the 35 million annual deaths attributable to chronic diseases worldwide occur in LMICs. Overweight and obesity comprise the fifth-leading cause of all deaths, with more than 3 million annual deaths attributed to it.4

In the U.S., obesity is evident among all races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic groups. However, a higher prevalence of adult obesity is found in some racial minorities, such as Latinos (38.7%), compared to whites/Anglos (25.6%).5,6 Latino adolescent boys are 40.0% more likely and girls 50.0% more likely to be overweight than their non-Latino white counterparts.7 For a considerable period of time, obesity and other NCD risk factors increased as a function of generational status in the U.S., with more exposure to the “Western lifestyle” resulting in higher prevalence of obesity and other risk factors among immigrants and their descendants.8 However, this pattern has taken a new and arguably ominous turn very recently. Mexico is now ranked as the second-most obese country in the world9 and is expected to surpass the U.S. soon. In addition, the prevalence of overweight or obese individuals in Latin America and the Caribbean is expected to reach 81.9% by 2030.10

Investigators in Latin America and other nations have expanded their focus to include NCD risk factors such as obesity. The shared economies, health threats and increasing migration among nations compel public health advocates to examine obesity and other public health challenges in a global context.11 Nowhere is this more evident than between the U.S. and Mexico, with their shared culture, history, and 2000-mile border.

The present review focuses on obesity-related interventions conducted in communities throughout Latin America and the U.S. The underlying goal of this review is to examine obesity control efforts aimed at Latinos in the U.S. and Latin America. Conducting this review also revealed gaps in the scientific literature. The findings aim to inform the development of evidence-based, culturally relevant strategies targeting obesity.

Evidence Acquisition

Search Strategy

The review was conducted by investigators and their staff at San Diego State University (SDSU) and the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, or INSP) between 2010 and 2011. Electronic databases were searched for articles and gray literature (dissertations) published between 1965 and December 31, 2010, including PsycINFO, MEDLINE/PubMed, Cinahl Information Services, Cochrane Library, Current Controlled Trials, LILACS, Global Health, Global Index Medicus, and Web of Science.

The primary key words (and their Spanish or Portuguese translations) aimed at the outcomes of interest that guided the search included BMI, weight, waist circumference, percent body, fat, overweight, and obese. Key words related to the outcome; intervention; comparison groups (e.g., control group and randomized controlled trial); Latino ethnicity; and geographic region (i.e., Latin American countries) were searched in combination with “and” statements.

Study Selection

Procedures for the literature review and intervention selection were adapted from The Community Guide, a resource provided by the CDC to inform and guide program and policy development.12 Potentially relevant articles were screened based on title and abstract. Full-text articles were retrieved for more-detailed evaluation based on seven inclusion criteria:

The intervention focused on obesity-related topics (i.e., weight loss, healthy eating, and physical activity).

The sample included at least 50.0% Latino/Latin American participants, or the results were stratified by race/ethnicity.

The intervention was evaluated and included obesity-related outcome measures.

The evaluated intervention compared participant exposure to the intervention to non-exposure or exposure in varying degrees. This included pre–post and crossover designs.

The intervention was conducted in a community setting, as opposed to a laboratory. Primary care settings were included.

The intervention did not focus solely on one-on-one health education, counseling, or advice in a healthcare setting (for a single participant).

The intervention details were published in a format with viable information for abstraction and quality evaluation.

Reviewers did not begin the screening process until a 90% inter-rater reliability was achieved based on training with example articles. Five reviewers (four from SDSU, one from INSP) conducted the screening process.

Data Collection and Abstraction

Two independent reviewers screened and evaluated each full-text article for inclusion in the review. For articles that met the inclusion criteria (Appendix A, available online at www.ajpmonline.org), two reviewers abstracted the details of the intervention into the CDC Community Guide’s online system for article abstraction. A third reviewer reconciled discrepancies during screening and abstraction. Quality evaluation of each study (i.e., the type and number of limitations) was conducted by investigators.

Evidence Synthesis

Suitability of study design was evaluated as greatest (concurrent comparison groups and prospective measurement of exposure and outcome); moderate (multiple pre or post measurements but no concurrent comparison group); and least (single pre and post measurements and no concurrent comparison group).13 Quality of the intervention or “execution” was based on nine possible limitations: (1) Was the study population and intervention well described? (2) Did authors specify the sampling frame? (3) Were there any selection bias issues? (4) Did authors attempt to measure that the exposure and exposure variables were valid and reliable? (5) Were the outcome and other independent variables valid and reliable measures of the outcome of interest? (6) Did authors conduct appropriate statistical testing? (7) Did at least 80% of enrolled participants complete the study? (8) Did authors assess confounding, potential biases, or unmeasured/ contextual confounders in the study? (9) Were there any other shortcomings that were not already mentioned elsewhere? Execution was categorized as good (zero to one limitations); fair (two to four limitations); or limited (five or more limitations).

On the basis of the number of available studies, the strength of their design and execution, and effect size, the body of evidence of effectiveness for each given category was rated as strong, sufficient, or insufficient (Table 1).13 When data were available, effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d. It was calculated as the difference between pre- and post-treatment scores divided by the pooled pre and post SDs [d=(x1 – x2)/s], where small was considered 0.0–0.19, medium 0.20–0.79, and large ≥0.80.14 For pre–post designs, Cohen’s d was calculated using the last follow-up measure.

Table 1.

Assessing the strength of a body of evidence on effectiveness of population-based interventions in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

| Evidence of effectivenessa |

Execution: good or fairb |

Design suitability: greatest, moderate, or least |

Number of studies |

Consistentc | Effect sized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Good | Greatest | ≥2 | Yes | Sufficient |

| Good | Greatest or moderate | ≥5 | Yes | Sufficient | |

| Good or fair | Greatest | ≥5 | Yes | Sufficient | |

| Design, execution, number and consistency criteria for sufficient but not strong evidence | Large | ||||

| Sufficient | Good | Greatest | 1 | N/A | Sufficient |

| Good or fair | Greatest or moderate | ≥3 | Yes | Sufficient | |

| Good or fair | Greatest, moderate, or least | ≥5 | Yes | Sufficient | |

| Insufficiente | A. Insufficient designs or execution | B. Too few studies | C. Inconsistent | D. Small | |

Note: Table is adapted from Briss et al.7

The categories are not mutually exclusive; a body of evidence meeting criteria for more than one of these is categorized in the highest possible category.

Studies with limited execution are not used to assess effectiveness.

Generally consistent in direction and size.

Sufficient and large effect sizes were calculated or, when lacking information, defined on a case-by-case basis.

Reasons for determination that evidence is insufficient is described as follows: (A) insufficient designs or executions; (B) too few studies; (C) inconsistent; (D) effect size too small; and (E) expert opinion not used. These categories are not mutually exclusive and one or more of these will occur when a body of evidence fails to meet the criteria for strong or sufficient evidence.

N/A, not applicable

Priority for recommendation development came from intervention strategies in the strong or sufficient body of evidence categories, with one exception stemming from expert opinion. The exception occurred in one category (adult healthcare-based interventions), for which investigators decided to label the evidence as “sufficient,” although it would have required one additional study to meet that criterion. Given the differing multinational study settings and resources available for research, it was necessary to obtain the opinions of experts familiar with research in the U.S., Mexico, and elsewhere in Latin America.

A total of 19,758 peer-reviewed articles and dissertations met search criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 325 (1.6%) were categorized as obesity-related interventions. Excluding interventions with same-source data, inclusion criteria were applied to 247 peer-reviewed articles and dissertations. When inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied, 113 (46.0%) passed; 134 studies did not meet criteria. Of those that met inclusion criteria, investigators excluded eight additional interventions because of the strict clinical nature of the interventions (surgical or pharmacologic obesity treatment), or to a focus on participants with mental health conditions (i.e., a sample consisting of only mentally disabled individuals). A final total of 105 interventions were included in this review. Fifty-three percent of studies were conducted in the U.S., 24.0% in Mexico, 15.0% in Brazil, and 8.0% in other Latin American countries, including Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela.

Figure 1.

Project GOL literature review flowchart

GOL, Guide to Obesity Prevention in Latin America and the U.S.

Categorizing Intervention Studies

For the 105 abstracted intervention studies, categories were assigned based on the authors’ literature review framework and CDC recommendations for community obesity interventions.13,15 Intervention categories included individual-based, family-based, Internet-based, healthcare-based, school-based, work-based, community level, environmental level, and policy and multilevel interventions. Separately for U.S. studies and Latin American studies and for both children and adults, interventions also were classified as prevention (e.g., not specifically targeting overweight or obese participants) or treatment (e.g., participants who were overweight or obese were recruited intentionally, and made up either the entire sample or part of the sample).

Evaluating the Body of Evidence

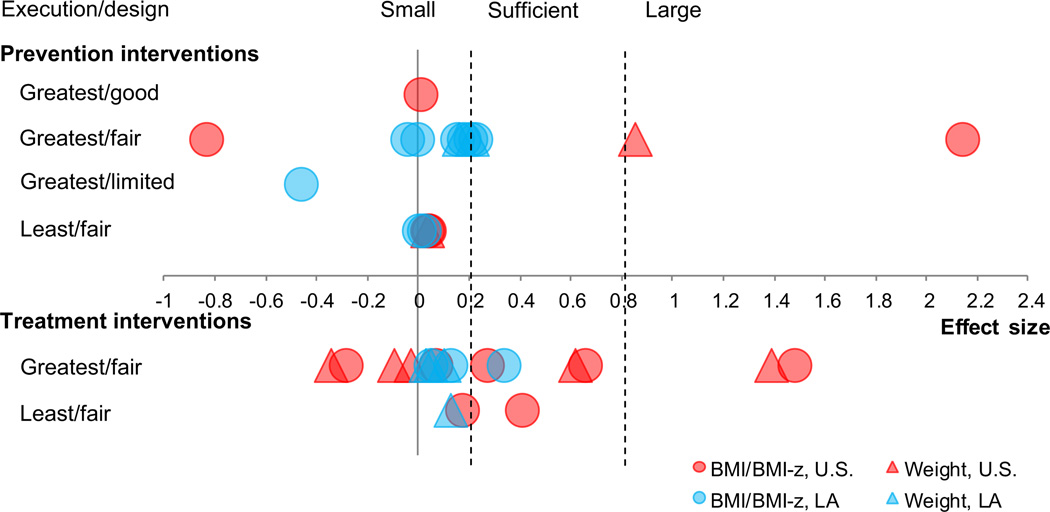

Among interventions aimed at children (Figure 2), 25.0% (n = 12) had zero to one limitation. Fifty-four percent (n = 26) of interventions were categorized as having greatest design suitability (i.e., having concurrent comparison groups or prospective measurement of exposure and outcome). For adult interventions (Figure 3), only 7.0% (n = 4) had zero to one limitation. Fifty-five percent (n = 32) of interventions were categorized as having greatest design suitability.

Figure 2.

Classification of interventions, based on study design, study execution, and effect size, for children

LA, Latin America

Figure 3.

Classification of interventions based on study design, study execution, and effect size, for adults

LA, Latin America

According to the CDC Community Guide guidelines and examination of number of studies, study design, execution, and effect size of all interventions, six intervention categories (as a group of interventions) achieved sufficient or strong evidence of effectiveness (three aimed at children and three aimed at adults). Individually, other interventions also may report effective approaches. Table 2 further outlines interventions by level of influence, focus of intervention strategy, prevention versus treatment, and country/region.

Table 2.

Obesity-related interventions with strong or sufficient evidence for recommendation by regiona

| Focus of intervention strategy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population/level of influence |

Physical activity | Healthy eating/nutrition | Both physical activity and healthy eating/nutrition |

|||

| Prevention | Treatment | Prevention | Treatment | Prevention | Treatment | |

| Children | ||||||

| Individual-level | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Family-based | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| School-based | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 (5)b | 4 |

| 3 (3)b | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Healthcare setting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 (3)b | |

| Worksite/organizational setting | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Environmental/policy | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Adults | ||||||

| Individual-level | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14 (6)c |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 9 (6)b | |

| Family-based | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| School-based | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Worksite/organizational setting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Healthcare setting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 (4)b | 0 | 1 | |

| Environmental/policy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Note: Values are n = total number of studies in category (number meeting recommendation criteria). Totals exceed number of abstracted articles (n = 105) because of interventions that are multilevel and are represented in more than one cell.

First row indicates studies from U.S.; second row indicates studies from Latin America.

Indicates sufficient evidence for recommendation

Indicates strong evidence for recommendation

Interventions Aimed at Children

School-based interventions to improve physical activity and healthy eating among Latino children in the U.S

Five studies provided sufficient evidence to recommend school-based interventions to improve physical activity and healthy eating in the U.S.16–20 Four interventions took place in elementary schools,17–20 and one took place among an inner-city, predominantly Latina, parochial high school.16 Two of the interventions were delivered by school staff or educators,17,18 and three were delivered by trained project staff or other professionals.16,18,20

Intervention durations ranged from 3.5 to 36 months, with varying frequency of contact (range: one to five times per week). Of the five interventions, two were group RCTs,17,18 two were non-RCTs,19,20 and one was a pre–post design.16 Each intervention had either one or two limitations in execution. BMI or BMI z-score was reported for four interventions,16– 18,20 and one reported percentage overweight/obese as the main outcome.19 Almost all interventions in this category were evaluated on a case-by-case basis with regard to effect size because of missing information needed for the calculation. It was determined that effect sizes were sufficient (i.e., significant difference between either intervention and control group or pre- and post-intervention measures).

For the one study with enough information to calculate effect size, a large effect was found for BMI (d = 1.03).18 Children in the intervention group had a lower mean change in weight (1.13 kg, SE = 0.12 kg) compared to the children in the control group (1.20 kg, SE = 0.12 kg). This study intervened with participants at least three times per week and included a parent component consisting of newsletters and homework assignments sent to the home to encourage interactive activity between child and parent.

School-based interventions to improve physical activity among children in Latin America

Three studies, one each from Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, provided sufficient evidence for school-based interventions aimed at increasing physical activity among children in Latin America.21–23 Two of the studies performed interventions at schools,22,23 and the third study intervention took place in a recreation center.21 Study duration ranged from 3 to 21 months, and frequency of intervention sessions ranged from once to twice per week. Two studies had a non-RCT design22,23; the third study was an RCT.21 Each intervention had one to three limitations in execution. Effect sizes ranged from 0.18 to 0.27 with an average effect size of 0.21.

The study with the largest effect size was a non-RCT delivered by teachers and trained nutritionists.23 Beyond regular physical education class time, students were exposed to 90-minute additional weekly physical education classes for children and active recess during 4 months. Among girls in this study, at post-intervention, the mean BMI for the intervention group was 20.1 (SD = 3.5); the control group had a mean BMI of 20.8 (SD = 3.8). Among boys at post-intervention, the mean BMI for the intervention group was 19.7 (SD = 3.2); the control group had a mean BMI of 20.6 (SD = 3.7).

Healthcare-based interventions to improve healthy eating and physical activity among obese or overweight children in Latin America

Three intervention studies targeting children provided sufficient evidence for recommending improving healthy eating and physical activity among patients in the primary care or health clinic setting.24–26 One intervention was conducted in Brazil24 and two in Mexico,25,26 all among overweight or obese children. Mexico included one RCT intervention26 and one pre–post design intervention,25 and the intervention in Brazil was an RCT.24

All studies in this category were delivered by healthcare professionals (e.g., a psychologist, a licensed nutritionist, a licensed dietician, or a physician), with duration of the intervention ranging from 4 to 12 months. Only one or two limitations in execution were given to each of these studies. Effect sizes for BMI were 0.22 and 0.41 for studies in Mexico25,26 and 1.13 for the study in Brazil24 (average BMI effect size = 0.58, median BMI effect size = 0.41).

The study with the largest effect size involved a variety of professionals who delivered a 16-week lifestyle and nutritional weight-loss program, including a psychologist, a physical trainer, and an endocrinologist.24 Those children who received both diet and exercise intervention components had a lower mean weight post-intervention (54.0 ± 2.1 kg) compared to the children who only received a diet component (58.6 ± 2.1 kg).

Interventions Aimed at Adults

Individual-based interventions to improve physical activity and healthy eating aimed at overweight or obese Latino adults in the U.S

Six intervention studies provided strong evidence to recommend improving physical activity and healthy eating among overweight or obese Latino adults in the U.S.27–32 Intervention settings varied, including classes delivered at community centers, healthcare organizations, and one church. Five of the interventions were conducted by a registered dietitian.27–30,32 Most interventions had a duration ranging from 2 to 6 months (n = 4), and two studies had interventions that lasted 12 months.28,31 Of six studies, five met at least once per week as part of the intervention.28–32 All of the studies had two to four limitations. Studies included three RCTs,27,28,31 two non-RCTs,29,32 and one pre–post design.30 The effect size of obesity-related measures (i.e., BMI and weight) ranged from 0.08 to 0.80, with an average effect size of 0.30.

The intervention with the highest effect size was an 11-week program given at a church and administered by a registered dietician.32 Sessions utilized conversation-style language, in addition to educational sessions on nutrition, physical activity, and cooking. Participants also kept a food and exercise diary. Over the course of this intervention, adults in the treatment group lost an average of 8.7 pounds; adults in the control group gained an average of 0.8 pounds.

Individual-based interventions to improve physical activity and healthy eating aimed at overweight or obese adults in Latin America

Six studies provided sufficient evidence to recommend individual-based interventions to increase physical activity and healthy eating in Latin America (four conducted in Mexico, two in Brazil).33–38 Three of the intervention settings were specified: two were conducted at a healthcare organization,33,34 and one within a university physical education department.35 Three of six articles described the qualifications of the people delivering the intervention, and these included nutritionists, psychologists, a physical education teacher, and research personnel.33–35 All of the studies were 6 months or shorter in duration. Frequency of intervention sessions, when reported, ranged from once per week to five times per week. Of the six interventions studies, one study received one limitation in execution,34 and all others ranged between two and four limitations.33,35–38 Three studies were RCTs,33–35 and three had a pre–post study design.36–38

Effect sizes for obesity-related measures (i.e., BMI and weight) ranged from 0.08 to 0.86, with an average effect size of 0.34. The intervention with the highest effect size had a pre–post design and delivered an individualized, tailored nutritional program with physical activity components.37 Over the course of this intervention, adults lost an average of 7.7 kg.

Healthcare-based interventions to increase healthy eating among overweight or obese adults in Latin America

Four studies provided sufficient evidence (based on expert opinion) to recommend healthcare-based interventions to increase healthy eating among overweight or obese adults in Latin America.39–42 Two studies took place in Mexico,41,42 one in Chile,40 and one in Brazil.39 Interventions were delivered by a range of healthcare workers such as physicians, therapists, dieticians, social workers, and other allied health professionals. Two studies were RCTs,39,42 and two studies had a pre–post design,40,41 ranging from 3 to 9 months in duration. One study received zero limitations in execution41; all others received two to three limitations.39,40,42 BMI effect sizes ranged from 0.08 to 0.86, with an average effect size of 0.51. One study, with weight as an outcome, was examined individually because of lack of information to calculate Cohen’s d and was determined to have sufficient effect sizes, as overall weight was reduced by 3.9% post-intervention (median reduction of 4.1 kg).40

Discussion

The present literature review is the first to examine evidence-based interventions targeting obesity-related outcomes among Latinos in the U.S. and Latin America. This review was able to point to some especially effective and well-executed studies. On the other hand, despite broad categorizations, this review was not able to identify studies in many intervention categories, including many environmental/policy-level studies, likely because the review criteria required individual-level measures (Table 1).

The first key finding is that there is sufficient evidence to recommend school-based interventions to improve physical activity, in both the U.S. and Latin America. Also, the largest effect size found in one school-based intervention included a component for parent participation. Of 25 school-based interventions for children, eight also included a parent component, of which five found significant changes in obesity-related outcomes. The support for school-based interventions in Latin America is consistent with previous research.43,44

In regard to school-based interventions in the U.S., there is sufficient evidence to recommend combining strategies that target physical activity with healthy eating. Prior school-based reviews in the U.S. have found mixed results or insufficient evidence, including the CDC Community Guide45,46; however, the current review specifically targets Latinos and includes the most recent findings in the field of school-based interventions. The addition of including parents in school-based interventions likely contributed to their success for Latino children, as it embraces an important cultural aspect, the family unit.

For children who are already overweight or obese, the current study found evidence to recommend interventions to improve healthy eating and physical activity in the healthcare context in Latin America. Studies in the U.S. found mixed results for interventions in this setting.46 However, healthcare settings may have a stronger influence on individuals’ health behaviors in developing countries and for cultures that hold physicians in high regard.47 In general, the most successful interventions in healthcare settings included longer intervention time (e.g., 16 weeks) and a multidisciplinary approach involving psychologists, physical trainers, and endocrinologists.

As with interventions targeting children, this review found evidence to recommend healthcare interventions aimed at improving physical activity and healthy eating among overweight adults in the U.S. (strong evidence) and in Latin America (sufficient evidence). No evidence was found to support prevention interventions for adults in either the U.S. or Latin America. Individual-based weight-loss programs increasingly are tailored toward individual participants’ own lifestyles and preferences.48–50 One advantage to tailoring is a greater potential for the development of culturally relevant interventions48,49; however, tailored programs may be difficult to implement and replicate.51

Limitations

Limitations of the present review include the sole focus on obesity-related measures as an outcome. Other approaches to healthy eating and physical activity promotion (some of which have been reviewed elsewhere; e.g., Hoehner43) also may reduce NCD risk independently of weight loss or weight control. In addition, other framework approaches for gathering and judging evidence on behavioral interventions, including promising and emerging interventions (e.g., Brennan52), may be complementary to the CDC Community Guide and appropriate for guiding public health action.

Another limitation is the relatively limited number of interventions, with the outcome of interest, that include environmental and policy domains. However, it is noted that few interventions at the population level are able to evaluate individual obesity-related data, which was necessary for judging the quality of the evidence under the CDC Community Guide approach. Finally, a common challenge for this type of review is that the effect sizes for studies with and without a control group are not necessarily comparable. Therefore, recommended interventions based on these types of dissimilar studies may not necessarily have enough external validity to be effective in improving obesity-related outcomes. For interventions to be effective, they need to reach a sufficient proportion of the population, be introduced with fidelity or necessary adaptations to the contextual issues associated with implementation, be acceptable to policymakers and the general public, and be sustainable.53

Conclusion

The present review showed that the most common and recommendable approaches to obesity prevention and control combined physical activity and healthy eating interventions to address both sides of the energy-balance equation, in both the U.S. and Latin America. For Latino children, school-based interventions provided favorable evidence for targeting obesity prevention efforts.16–23 For Latino adults, individually based, tailored interventions provided the most promise for the treatment of those who were already overweight or obese.27–38

Intervention in the healthcare context, for both children and adults, also showed great potential to prevent and treat obesity within the Latino population.24–26,39–42 Given the various settings and approaches that showed sufficient evidence to combat obesity, a coordinated, multi-sector approach is more likely to influence policy and increase investment in monitoring, prevention, and control. With the exigency presented by the spreading epidemic of overweight and obesity, an important research priority may be to put more resources into rigorous evaluation of promising but yet unproven interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the CDC, Grant Number 1U48 DP001917; publication of the article was supported through the same CDC grant.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

A pubcast created by the authors of this paper can be viewed at www.ajpmonline.org/content/video_pubcasts_collection.

References

- 1.WHO. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet No 311. 2011 www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html.

- 2.WHO. 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. 2008 www.who.int/nmh/Actionplan-PC-NCD-2008.pdf.

- 3.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438–1447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among U.S. adults, 1999 –2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman DS. Obesity—U.S., 1988–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Office of Minority Health. Obesity and Hispanic Americans. 2011 minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?lvl_3&lvlID_537&ID_6459.

- 8.Popkin BM. Technology, transport, globalization and the nutrition transition food policy. Food Policy. 2006;31(6):554–569. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NationMaster. Health statistics, obesity (most recent) by country. 2011 www.nationmaster.com/graph/hea_obe-health-obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen C-S, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes. 2008;32(9):1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayan KMV, Ali MK, Koplan JP. Global noncommunicable diseases—where worlds meet. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1196–1198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC; The community guide homepage. 2011 www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html.

- 13.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1S):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris SB. Distribution of the standardized mean change effect size for meta-analysis on repeated measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2000;53(Pt 1):17–29. doi: 10.1348/000711000159150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guide to community preventive services. Obesity prevention and control: interventions in community settings. www.thecommunityguide.org/obesity/communitysettings.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chehab LG, Pfeffer B, Vargas I, Chen S, Irigoyen M. “Energy Up”: a novel approach to the weight management of inner-city teens. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):474–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J, et al. Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: the El Paso coordinated approach to child health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, et al. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(9):1616–1625. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoelscher DM, Springer AE, Ranjit N, et al. Reductions in child obesity among disadvantaged school children with community involvement: the Travis County CATCH Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(S1):S36–S44. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollar D, Lombardo M, Lopez-Mitnik G, et al. Effective multi-level, multi-sector, school-based obesity prevention programming improves weight, blood pressure, and academic performance, especially among low-income, minority children. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2S):93–108. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macias-Cervantes MH, Malacara JM, Garay-Sevilla ME, Díaz-Cisneros FJ. Effect of recreational physical activity on insulin levels in Mexican/Hispanic children. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(10):1195–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farias ES, Paula F, Carvalho WR, Gonçalves EM, Baldin AD, Guerra-Júnior G. Influence of programmed physical activity on body composition among adolescent students. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2009;85(1):28–34. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kain J, Leyton B, Cerda R, Vio F, Uauy R. Two-year controlled effectiveness trial of a school-based intervention to prevent obesity in Chilean children. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(9):1451–1461. doi: 10.1017/S136898000800428X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prado DM, Silva AG, Trombetta IC, et al. Weight loss associated with exercise training restores ventilatory efficiency in obese children. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30(11):821–826. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1233486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velazquez Lopez L, Rico Ramos JM, Torres Tamayo M, et al. The impact of nutritional education on metabolic disorders in obese children and adolescents. Endocrinol Nutr. 2009;56(10):441–446. doi: 10.1016/S1575-0922(09)73311-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz RG, Esparza-Romero J, Moya-Camarena SY, Robles-Sardin AE, Valencia ME. Lifestyle intervention in primary care settings improves obesity parameters among Mexican youth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(2):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West DS, Prewitt TE, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the diabetes prevention program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(6):1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cousins JH, Rubovits DS, Dunn JK, et al. Family versus individually oriented intervention for weight loss in Mexican American women. Public Health Rep. 1992;107(5):549–555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordan KC, Freeland-Graves JH, Klohe-Lehman DM, et al. A nutrition and physical activity intervention promotes weight loss and enhances diet attitudes in low-income mothers of young children. Nutr Res. 2008;28(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke KK, Freeland-Graves J, Klohe-Lehman DM, et al. Promotion of physical activity in low-income mothers using pedometers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(6):962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(4):713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SB. Denton TX: Texas Women’s University; 1990. Weight control for low-income black and Hispanic women [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saes Sartorelli D. Sao Paulo, Brazil: Universidade de Sao Paulo; 2003. A randomized nutritional intervention study in overweight adults in a basic health unit [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Hernandez H, Morales-Amaya UA, Rosales-Valdéz R, et al. Adding cognitive behavioural treatment to either low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets: differential short-term effects. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(12):1847–1853. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carneiro J, Silva M, Vieira M. Effects of pilates method and training with weights in the kinematics of gait in obese women. Braz J Biomech. 2009;9(18):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chavez Regalado S. Coyoacán, Mexico: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco; 2007. Nutrition in primary care: overweight and obesity [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz Cisneros FJ. Effects of an aerobic exercise program and diet on body composition and cardiovascular function in obese patients. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1986;56(6):527–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominguez Carrillo LG, Arellano Aguilar G. Effects of submaximal aerobic exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity or overweight. Acta Medica Grupo Angeles. 2004;2(4):227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borges RL, Ribeiro-Filho FF, Baiocchi Carvalho KM, Zanella MT. Impact of weight loss on adipocytokines, C-reactive protein and insulin sensitivity in hypertensive women with central obesity. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89(6):409–414. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007001800010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrasco F, Moreno M, Irribarra V, et al. Evaluation of a pilot intervention program for overweight and obese adults at risk of type 2 diabetes. Rev Med Chile. 2008;136(1):13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernandez Aceves CC, Canales Munoz JL, Cabrera Pivaral C, Grey Santacruz C. Effects of nutritional counseling in reducing obesity in health workers. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2003;41(5):429–435. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabrera-Pivaral CE, Gonzalez-Perez G, Vega-Lopez MG, Arias-Merino ED. Impact of participatory education on body mass index and blood glucose in obese type-2 diabetics. Cad Saude Publica. 2004;20(1):275–281. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000100045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoehner CM, Soares J, Parra Perez D, et al. Physical activity interventions in Latin America: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ribeiro IC, Parra DC, Hoehner CM, et al. School-based physical education programs: evidence-based physical activity interventions for youth in Latin America. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(2):5–15. doi: 10.1177/1757975910365231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4S):73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz DL, O’Connell M, Yeh M-C, et al. Public health strategies for preventing and controlling overweight and obesity in school and worksite settings: a report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(RR–10):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Chadwick Center. Latino adaptation guidelines-cultural values. www.chadwickcenter.org/Documents/WALS/Adaptation Guidelines - Cultural Values Priority Area.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skinner CS, Campbell MK, Rimer BK, Curry S, Prochaska JO. How effective is tailored print communication? Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):290–298. doi: 10.1007/BF02895960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02895958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR, et al. Long-term effects of a communication intervention for Spanish-dominant Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ayala GX, Elder JP, Campbell NR, et al. Longitudinal intervention effects on parenting of the Aventuras para Niños study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brennan L, Castro S, Brownson RC, Claus J, Orleans CT. Accelerating evidence reviews and broadening evidence standards to identify effective, promising, and emerging policy and environmental strategies for prevention of childhood obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:199–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.