Abstract

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) play fundamental roles in regulating gene expression. HAT complexes with distinct subunit composition and substrate specificity act on chromatin-embedded genes with different promoter architecture and chromosomal locations. Because requirements for HAT complexes vary, a central question in transcriptional regulation is how different HAT complexes function in different chromosomal contexts. Here, we have tested the ability of targeted yeast HATs to regulate gene expression of an epigenetically silenced locus. Of a panel of HAT fusion proteins targeted to a telomeric reporter gene, Sas3p and Gcn5p selectively increased expression of the silenced gene. Reporter gene expression was not solely dependent on acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT. Further analysis of Gcn5p-mediated gene expression revealed collateral requirements for HAT complex subunits Spt8p and Spt3p, which interact with TATA-binding protein, and for a gene-specific transcription factor. These data demonstrate plasticity of gene expression mediated by HATs upon encountering novel promoter architecture and chromatin context. The telomeric location of the reporter gene used in these studies also provides insight into the molecular requirements for heterochromatin boundary formation and for overcoming transcriptional silencing.

A number of studies have investigated the molecular requirements of transcriptional activation mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) for genes normally requiring their function (reviewed in references 11 and 65). Results from these studies with yeast reveal a complex network of gene-specific and HAT-specific contributions to activation. Gene-specific effects arise from differing chromatin environments and promoter architecture of individual genes, whereas HAT-specific effects arise from distinct substrate specificities of these enzymes and their participation in multiprotein complexes. Understanding of the discrete roles of HAT complex subunits, as well as the significance of site-specific acetylation, is just emerging. The histone H3/H2B-specific HATs, Gcn5p and Sas3p, participate in HAT complexes distinct from each other and from the H4/H2A-specific HATs, Esa1p and Hat1p. Because requirements for HAT complex function vary from gene to gene, a central question in transcriptional regulation is how different HAT complexes bring about common steps in transcription, such as relief of chromatin-induced repression, formation of a preinitiation complex, and initiation of transcription.

HATs can be targeted to specific gene promoters to regulate their transcription (reviewed in reference 11) and can exert more long-range effects through acetylation of extended genomic regions that are not promoter proximal (84). One mechanism of HAT complex selectivity is recruitment to target gene promoters through interaction with gene-specific transcription factors (6, 12, 32, 47, 58, 59). For example, Gcn5p acts in a temporal procession of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to activate the HO endonuclease gene (25, 56). In this case, the gene-specific transcription factor Swi5p first binds the HO promoter, followed by the SWI/SNF complex, and then the Gcn5p-containing SAGA complex. In contrast, the Gal4p transcription factor directly recruits SAGA to the GAL1 gene (6, 59). Activation requires the SAGA subunit Spt3 and its ability to recruit TATA-binding protein (TBP) (32), but unlike activation at HIS3 (57), it is independent of Gcn5p activity (6, 59). Because multiple gene-specific and HAT-specific effects are operating in these cases, it is difficult to distinguish common functional requirements for gene expression.

The composition of the Gcn5p-containing SAGA complex yields clues to key steps in activation that may be commonly required by HAT complexes. Of the 14 subunits now known to be present in the SAGA complex, 8 of these either are bona fide RNA polymerase II (Pol II) TFIID components (TAFs 17, 25, 60, 61/68, and 90) or interact with TBP (Spt3, Spt8p, and Ada2p) (4, 32, 35, 36, 75), suggesting that recruiting or mimicking TFIID is important for activation. Thus, subunits present in SAGA are likely to modulate its activation potential at individual promoters.

We sought to define fundamental requirements for HAT-mediated gene expression in a context in which promoter-specific and HAT recruitment effects were minimized but which instead required overcoming repressive effects of silent chromatin, which are largely gene nonspecific. We directly targeted a panel of HATs downstream of a gene present in a telomeric chromosomal context that is not normally regulated by these HATs. We observed that some, but not all, HATs tested could alter gene expression. Further, reporter gene expression was not solely dependent on acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT, and it required HAT complex subunits known to associate with TBP. Due to the telomeric location of the URA3 reporter gene analyzed, these observations on HAT targeting also provide insight into the molecular requirements of boundary formation between euchromatic and heterochromatic regions of the genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Control plasmids were pRS313 (73) (HIS3, CEN) and pMA-424 (63) (Gal4p DNA binding domain [GBD] encoding the Gal4p DNA binding domain amino acids [aa] 1 to 147). For GBD-SAS3 (pLP 624), an NsiI-HindIII fragment of SAS3 (encoding aa 17 to 639) was cloned downstream of the GBD cassette of pMA-424. The function of this SAS3 construct was demonstrated by rescue of the synthetic lethality of a sas3Δgcn5Δ strain. For GBD-ESA1 (pLP 1372), GBD-GCN5 (pLP 871), and GBD-gcn5 (KQL126-128AAA; pLP 1373), full-length genes were generated by PCR and cloned downstream of the GBD cassette. GBD-sas3(C323A) (pLP 1565) was constructed by cloning a 1.9-kb BamHI-SalI fragment containing the NsiI-HindIII segment of SAS3 with the C323A mutation into pMA424 downstream of the GBD cassette at the BamHI-SalI sites. GBD-HAT1 (pLP 941) was a gift from R. Sternglanz. GBD-TBP (pLP 947) was constructed in the laboratory of J. Lis (86) and provided by R. Morse. Yeast strains used for the tethering assay were derived from those originally reported by Chien et al. (22). LPY 1030 is a derivative of the W303 background and is of the genotype MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can 1-100 with telomeric adh4::URA3-UASGAL-(C1-3A)n. The presence of a single UASGAL was verified by sequencing genomic DNA in this region from three independent isolates. The control strain LPY 1029 is isogenic to LPY 1030 but lacks the engineered telomeric UASGAL site. LPY 1030 strains with a deletion of SPT8 (LPY 5843), SPT3 (LPY 6486), ANC1 (LPY 5866), or PPR1 (LPY 5973) were constructed by replacing the entire open reading frame with a KANMX cassette, thereby making these strains resistant to G418. The yng1Δ::LEU2 tethering strain (LPY 8873), which is otherwise isogenic to LPY 1030, was generated by a standard genetic cross. A complete list of strains used in this study, with their corresponding identification numbers, is provided in Table 1. A list of plasmids used in this study is provided in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in HAT targeting studies

| Strain no. | Genotype |

|---|---|

| LPY 1030 | MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3, 112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can1-100 with telomeric adh4::URA3-UASGAL-(C1-3A)na |

| LPY 4408 | LPY 1030 with vector (pRS313) |

| LPY 2846 | LPY 1030 with GBD (pMA-424) |

| LPY 2735 | LPY 1030 with GBD-Sas3p (pLP 624) |

| LPY 5822 | LPY 1030 with GBD-Esa1p (pLP 1372) |

| LPY 3198 | LPY 1030 with GBD-Gen5p (pLP 871) |

| LPY 3768 | LPY 1030 with GBD-Hat1p (pLP 941) |

| LPY 5823 | LPY 1030 with GBD-gen5(KQL) (pLP 1373) |

| LPY 5824 | LPY 1030 with GBD-gen5(FKK) (pLP 1374) |

| LPY 6827 | LPY 1030 with GBD-sas3(C323A) (pLP1565) |

| LPY 1029 | As LPY 1030, except lacking the telomeric UASGAL tethering site |

| LPY 4404 | LPY 1029 with vector |

| LPY 2836 | LPY 1029 with GBD |

| LPY 2734 | LPY 1029 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 5819 | LPY 1029 with pLP 1372 |

| LPY 3195 | LPY 1029 with pLP 871 |

| LPY 3764 | LPY 1029 with pLP 941 |

| LPY 5820 | LPY 1029 with pLP 1373 |

| LPY 5821 | LPY 1029 with pLP 1374 |

| LPY 5843 | As LPY 1030, except spt8:Δ:KANMXb |

| LPY 5946 | LPY 5843 with GBD |

| LPY 5950 | LPY 5843 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 5952 | LPY 5843 with pLP 871, isolate 1 |

| LPY 5953 | LPY 5843 with pLP 871, isolate 2 |

| LPY 5847 | LPY 5843 with pLP 871, isolate 3 |

| LPY 5954 | LPY 5843 with pLP 1373, isolate 1 |

| LPY 5955 | LPY 5843 with pLP 1373, isolate 2 |

| LPY 5848 | LPY 5843 with pLP 1373, isolate 3 |

| LPY 5960 | LPY 5843 with pLP 947 (GBD-TBP) |

| LPY 8864 | LPY 5843 with pLP 1565 |

| LPY 6486 | As LPY 1030, except spt3Δ::KANMXb |

| LPY 6589 | LPY 6486 with GBD |

| LPY 6594 | LPY 6486 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 6597 | LPY 6486 with pLP 871, isolate 1 |

| LPY 6598 | LPY 6486 with pLP 871, isolate 2 |

| LPY 6599 | LPY 6486 with pLP 871, isolate 3 |

| LPY 6601 | LPY 6486 with pLP 1373, isolate 1 |

| LPY 6602 | LPY 6486 with pLP 1373, isolate 2 |

| LPY 6603 | LPY 6486 with pLP 1373, isolate 3 |

| LPY 6605 | LPY 6486 with pLP 947, isolate 1 |

| LPY 6606 | LPY 6486 with pLP 947, isolate 2 |

| LPY 8873 | As LPY 1030 except yng1Δ::LEU2 |

| LPY 8943 | LPY 8873 with GBD |

| LPY 8945 | LPY 8873 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 8947 | LPY 8873 with pLP 1565 |

| LPY 8949 | LPY 8873 with pLP 871 |

| LPY 8951 | LPY 8873 with pLP 1373 |

| LPY 8953 | LPY 8873 with pLP 947 |

| LPY 5866 | As LPY 1030, except anc1Δ::KANMXb |

| LPY 7008 | LPY 5866 with GBD |

| LPY 7016 | LPY 5866 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 7018 | LPY 5866 with 1565 |

| LPY 5973 | As LPY 1030, except ppr1::KANMXb |

| LPY 6043 | LPY 5973 with GBD |

| LPY 6045 | LPY 5973 with pLP 624 |

| LPY 6047 | LPY 5973 with pLP 871 |

| LPY 6049 | LPY 5973 with pLP 1373 |

| LPY 6053 | LPY 5973 with pLP 947 |

Strains containing plasmids are listed below their respective parental strain numbers: LPY 1030, LPY 1029, LPY 5843, LPY 6486, LPY 8873, LPY 5866, or LPY 5973. Plasmids expressing fusion proteins are 2μm copy number and are marked with HIS3.

Complete start-to-stop gene deletions in LPY 1030 were constructed by PCR amplifying genomic DNA containing the KANMX gene deletion cassette from the appropriate Research Genetics strain, followed by transformation of this gene disruption cassette into LPY 1030.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in HAT targeting studies

| Plasmid no. | Descriptiona |

|---|---|

| pRS313 | Vector control |

| pMA-424 | GBD control |

| pLP 624 | GBD-SAS3 (encoding aa 17 to 639) |

| pLP 1372 | GBD-ESA1 |

| pLP 941 | GBD-HAT1b |

| pLP 871 | GBD-GCN5 |

| pLP 1373 | GBD-gcn5 (KQL) |

| pLP 1565 | GBD-sas3(C323A) |

| pLP 947 | GBD-TBPb |

| pLP 646 | GBD-SAS2 |

All vectors are marked with HIS3.

See Materials and Methods for sources.

Cell plating assays.

URA3 reporter gene expression was assayed by plating fivefold dilutions of cells onto media selecting for a plasmid expressing a GBD-HAT fusion protein. In control experiments, a plasmid-borne URA3 gene was unaffected by deletion or mutation of the HATs under investigation here (data not shown) and therefore was selected as a reporter gene. Cells were plated on medium lacking histidine (His−) to assess cell plating equivalence (growth) or His− medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) to assess relative expression levels of the URA3 reporter gene. Decreased growth on 5-FOA indicates increased URA3 expression.

Protein immunoblotting.

Whole-cell lysates from 5 × 106 cells were prepared by glass bead lysis (77) and subjected to electrophoresis on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-7.5% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Micron Separations, Inc., Westborough, Mass.) and probed with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-GBD serum (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, Calif.) at a 1:150 dilution, followed by incubation with goat antimouse serum (Promega, Madison, Wis.) at a 1:5,000 dilution. Control antiserum used in Western blots with LPY 5843-derived strains was anti-CPY (directed toward yeast vacuolar carboxypeptidase; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Ore.), used at a 1:2,000 dilution, followed by incubation with goat antimouse serum (Promega) at a 1:5,000 dilution.

RNase protection assay.

Strains were as shown in Fig. 1A but were deleted for the chromosomal ura3-1 locus and therefore harbored only the functional telomeric URA3 gene. Cells grown in synthetic medium lacking histidine were harvested at an optical density of 1.0, lysed by hot acidic phenol extraction, and subjected to RNase digestion using antisense RNA transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) from pLP 366 (ACT1) or pLP 1262 (URA3). RNA from 1.6 × 108 cells was hybridized to an antisense 32P-labeled URA3 probe (nucleotides 510 to 668) or ACT1 control probe (nucleotides 1183 to 1319). URA3 mRNA levels were measured in strains derived from the LPY 1030 tethering strain containing the ura3Δ0 chromosomal allele. Thus, only URA3 mRNA expressed from the telomeric reporter gene was detected. After a 60-h phosphorimaging exposure, signals were quantitated using ImageQuant software.

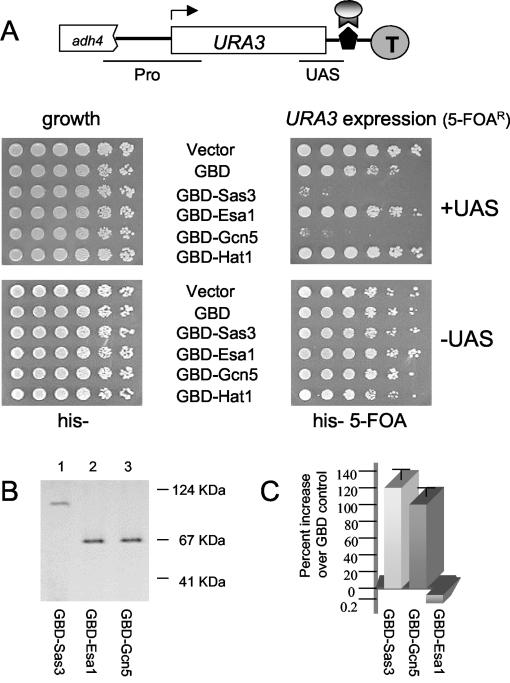

FIG. 1.

Targeted GBD-Sas3p and GBD-Gcn5p selectively increase expression of a normally silenced gene. (A) Telomeric tethering assay. URA3 reporter gene expression was assayed by plating fivefold dilutions of cells onto media selecting for a plasmid expressing a GBD-HAT fusion protein. Cells were plated on His− medium to assess cell plating equivalence (left panel, growth) or His− medium containing 5-FOA to assess relative expression levels of the URA3 reporter gene (right panel, URA3 expression). Decreased growth on 5-FOA indicates increased URA3 expression. The diagram shows the telomere VIIL reporter (22). The URA3 cassette (0.8-kb URA3 gene with approximately 300-bp 5′ and 65-bp 3′ chromosomal flanking sequences) was engineered between a truncated chromosomal ADH4 gene on telomere VIIL and an 85-bp insert containing a single upstream activating sequence (UASGAL) recognized by the Gal4 protein. Circled T, telomeric sequences; arrow, URA3 transcription start site; pentagon, UASGAL; lunar landing module, GBD-HAT fusion protein; solid lines denote regions amplified by PCR in chromatin immunoprecipitation studies (Fig. 2). The URA3 promoter region (Pro) and telomere-proximal region (UAS) are indicated. Lists of strains and plasmids used in this study are provided in Tables 1 and 2. (B) In vivo expression levels of GBD-HAT fusion proteins determined by protein immunoblotting with anti-GBD antiserum. Lane 1, GBD-Sas3p; lane 2, GBD-Esa1p; lane 3, GBD-Gcn5p. Positions of molecular mass markers are noted at right. (C) URA3 mRNA levels in cells expressing GBD-HAT fusion proteins determined by an RNase protection assay. URA3 mRNA levels are represented in graphical form from cells expressing the GBD control (LPY 4942), GBD-Sas3p (LPY 4948), GBD-Gcn5p (LPY 4950), or GBD-Esa1 (LPY 5830). Quantitation was performed using ImageQuant software (see Materials and Methods for details). Percent increases in GBD-Sas3p, GBD-Gcn5p, and GBD-Esa1p (negative control) were plotted for each targeted HAT and were calculated by determining the ratio of URA3 signal in cells expressing the GBD-HAT fusion proteins compared to the GBD control and then normalizing this to the respective ACT1 mRNA ratios.

ChIPs.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed as described previously (40) using anti-acetylated K9/K14 histone H3 (Upstate, Waltham, Mass.) or anti-acetylated H4 sera (Serotec, Raleigh, N.C.). Oligonucleotides used for PCR are as follows: URA3 promoter region (Pro), truncated ADH4 gene on telomere VIIL (5′ GCCATACCTGCCAAGTATTCAGCG 3′) and URA3 gene on telomere VIIL (5′ CCGTCGAGATCCGTCGAGGGTAATAACTG 3′); URA3 UAS region (UAS) (5′ CAACAGTATAGAACCGTGGATGATG 3′ and 5′ CCGTCGAGATCCGCGAGGGTAATAACTG 3′); TELVIR-S (5′ CCGCCAAGCTTCCAATATCACGAGTAAGG 3′ and TELVIR-C 5′ GTCCAGCCGCTTGTTAACTCTCCGACAG 3′); and INO1 (5′ CGCTCTTTATCACCGTAGTTCTAAATAACACC 3′ and 5′ CCCGACAACAGAACAAGCCAAAAAAAGGTGACG 3′).

RESULTS

Targeted Sas3p and Gcn5p selectively increased expression of a silenced gene not normally responsive to these HATs. To test whether HATs can alter gene expression when targeted near a gene not normally requiring their function, HAT proteins were fused to an N-terminal GBD (GBD1-147) and directed to a telomere-proximal URA3 reporter gene harboring a downstream Gal4p binding site (UASGAL) (Fig. 1A). In this telomeric location, the URA3 gene exists in an epigenetic transcriptional state that is capable of switching between active and silenced states. Upon binding of the HAT fusion protein to its cognate UASGAL element, either increases or decreases in URA3 gene expression can be quantitatively monitored by a colony-based dilution assay (83).

We began the targeting analysis with Sas3p, the catalytic component of the NuA3 complex that acetylates histone H3 (51). We constructed a chimeric HAT in which GBD1-147 was fused to an extended HAT domain of SAS3 (encoding aa 17 to 639). When targeted to the telomere-proximal URA3 reporter gene, this GBD-Sas3p chimera significantly increased URA3 expression. This increased gene expression was observed as a >1,000-fold decrease in the number of CFU on 5-FOA-containing medium, compared to cells transformed with vector or GBD control plasmids (Fig. 1A, upper right panel). Cells expressing the URA3 gene product are sensitive to the suicide substrate 5-FOA and are therefore unable to grow on medium containing this compound (9). This level of URA3 expression is reminiscent of that observed in cells with deletions in the silent information regulator gene, SIR2, SIR3, or SIR4, which completely disrupt telomeric gene silencing (data not shown) (2).

Several lines of evidence indicated that increased URA3 expression was not due simply to elevated dosage of the GBD-Sas3 fusion protein, possibly causing nonspecific titration or inactivation of silencing factors. First, control strains expressing GBD-Sas3p but lacking the telomeric targeting sequence (−UAS) showed no detectable change in URA3 expression (Fig. 1A, lower right panel). Second, chromosomal deletion of SAS3 did not affect repression of a telomeric reporter gene (70), demonstrating its lack of direct involvement in telomeric silencing. Third, tethering GBD-Sas3p to the URA3-containing telomere did not increase expression of an independent reporter gene at a separate telomere (data not shown).

To test whether GBD-Sas3p-mediated URA3 expression was a general property of the MYST (named for yeast and human members MOZ, YBF2 [SAS3], SAS2, and Tip60) family of HATs (18, 31), we assayed changes in URA3 expression upon targeting of GBD-Esa1p. Esa1p primarily acetylates nucleosomal histone H4 (24, 74) in the context of the NuA4 complex, which can mediate transcriptional activation in vitro (1). Although Sas3p and Esa1p are both MYST family HATs, they differ in cellular function, histone substrate specificity, and HAT complex composition (reviewed in reference 81). Targeted GBD-Esa1p did not increase URA3 expression (Fig. 1A, upper right panel). Control experiments demonstrated that this Esa1p chimeric protein complemented the esa1 mutant temperature-sensitive phenotype and that it was expressed at a level similar to that of GBD-Sas3p and GBD-Gcn5p (Fig. 1B). Thus, acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT was not itself sufficient for increased gene expression, even for a HAT with established roles in transcriptional activation (1, 34, 39, 69).

To further investigate HAT substrate requirements for gene expression, the deposition-related H4-specific acetyltransferase Hat1p (55, 67) was examined in this assay. Like GBD-Esa1p, GBD-Hat1p failed to increase URA3 expression (Fig. 1A, upper right panel). However, this was probably not simply due to H3 versus H4 acetylation, since GBD-Sas2p, a MYST family histone H4-specific HAT (80) involved in silencing (64), increased URA3 expression to levels similar to those with GBD-Sas3p (data not shown). Importantly, the inability of GBD-Esa1p and GBD-Hat1p to elevate URA3 expression emphasizes that HAT-mediated gene expression in this assay was specific and not a universal property of HATs. It also demonstrated that HATs targeted to this telomeric location did not cause nonspecific steric hindrance to the proper assembly and function of telomeric silencing complexes.

Because histone substrate specificity and HAT complex composition contribute to transcriptional regulation, we tested whether GBD-Gcn5p elevated URA3 expression upon targeting. Gcn5p, like Sas3p, acetylates histone H3 primarily on lysine 14 (13, 46). However, they apparently have distinct cellular functions, because whereas SAS3 and GCN5 null mutants are fully viable, cells with mutations in both genes are dead (46). Gcn5p participates in several yeast HAT complexes (SAGA, Ada, and SLIK/SALSA) whose subunit compositions differ from that of Sas3p-containing NuA3 (41, 51, 68, 76). We observed that GBD-Gcn5p increased URA3 expression to a level similar to that with GBD-Sas3p by colony growth assay (Fig. 1A, upper right panel).

Furthermore, steady-state URA3 mRNA levels were increased in cells expressing GBD-Sas3p and GBD-Gcn5p, as analyzed by RNase protection analysis (Fig. 1C), confirming that the colony growth assay reflected changes in URA3 transcription. Fold changes upon targeting of Gcn5p and Sas3p are not large, due to the epigenetic regulation of the telomere-proximal URA3 gene, where without the negative selection of 5-FOA, approximately 50% of cells express URA3 in an unperturbed state (2).

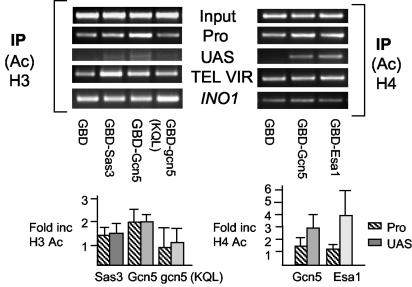

To determine if GBD-Sas3p or GBD-Gcn5p caused increased histone H3 acetylation near the site of tethering, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed. GBD-Gcn5p and to a lesser extent GBD-Sas3p increased histone H3 acetylation at the targeting site (UAS) and at the promoter region (Pro) of the URA3 gene compared to results with the control plasmid GBD (Fig. 2, left panel). The acetylated H3 at the UAS site upon tethering of Gcn5p is discernible but weak due to its immediate proximity to the nonnucleosomal telomere. Control PCRs on the uninduced SAGA-dependent gene INO1 showed no detectable increase in K9/K14 histone H3 acetylation in cells expressing GBD-Sas3p or GBD-Gcn5p (Fig. 2, left panel). Interestingly, PCRs for a control, nontargeted telomere (VI) showed increased telomere-proximal H3 acetylation in cells expressing GBD-Sas3p, although this HAT is not known to function in telomeric silencing (70). Analysis of histone H4 acetylation levels at the HAT-targeted telomere showed an increase at the UAS upon targeting of Esa1p compared to results with the control GBD plasmid (Fig. 2, right panel), although as noted above, there was no elevated expression of the URA3 gene. This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that acetyltransferase activity of a targeted HAT may not be the critical determinant of gene activation. As expected, H4 acetylation was clearly detectable at the less telomere-proximal Pro region of the targeted telomere in cells expressing the GBD control, and H4 acetylation was slightly increased upon targeting of GBD-Esa1p. Interestingly, targeted Gcn5p also increased histone H4 acetylation at the UAS and Pro regions, which may correlate with the loss of telomeric silencing upon targeting of this HAT.

FIG. 2.

In vivo nucleosomal histone H3 and H4 acetylation at telomere VII targeted by HAT fusion proteins, determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Solubilized formaldehyde-cross-linked chromatin from 2 × 106 cells was immunoprecipitated (IP) with antiserum directed toward acetylated histone H3 [anti-K9/K14 (Ac) H3] or acetylated histone H4 [anti-(Ac) H4]. Input, DNA recovered from cross-linked chromatin extracts prior to IP was amplified with oligonucleotides specific for the promoter region of the URA3 gene. This signal was used to normalize changes in H3 and H4 acetylation among IP samples from cells expressing GBD-HAT constructs. IP, DNA recovered from cross-linked chromatin extracts after IP with anti-(Ac) H3 or anti-(Ac) H4 was amplified with oligonucleotides specific for the URA3 promoter (Pro; 550 bp) or for the HAT targeting region (UAS; 200 bp). DNA amplified by PCR (upper panels) was quantitated, and relative band intensities are depicted in graphical form below. Control reactions using immunprecipitated DNA with oligonucleotides specific for an uninduced INO1 gene and for an untargeted telomere (TEL VIR) are shown in the upper panels. Data are representative of four independent experiments and are equivalent dilutions of samples in which amplification was in the linear range. Quantitation was performed using ImageQuant software.

Acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT was not the sole determinant of increased gene expression.

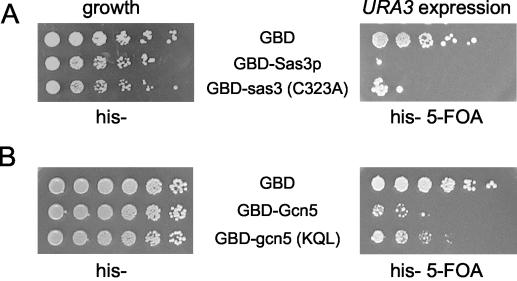

To test whether GBD-HAT enzymatic activity was important for increased URA3 expression, a catalytically inactive form of Sas3p (GBD-sas3C323Ap) that fails to rescue the sas3Δ gcn5Δ synthetic lethality (46) was directed to the telomere. Surprisingly, GBD-sas3C323Ap increased URA3 expression to the same level as that of wild-type GBD-Sas3p (Fig. 3A, right panel). This indicated that full acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT was not strictly required for increased URA3 expression. To determine if elevated URA3 expression induced upon targeting of GBD-Gcn5p was also HAT independent, a mutant form of Gcn5p (KQL124-126AAA) that destroys HAT activity in the context of native SAGA and/or Ada complexes (85) was analyzed. Tethered GBD-gcn5(KQL) likewise increased URA3 expression similarly to wild-type GBD-Gcn5p (Fig. 3B, right panel). Thus, acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT was not solely required for URA3 expression in this context. These observations also demonstrate that HAT-independent activation was a property shared by both targeted Sas3p and Gcn5p. It is unlikely that another HAT is substituting for GBD-gcn5p activity at the telomere, because the elevated histone H3 acetylation at the site of tethering caused by wild-type GBD-Gcn5p was abolished in cells expressing mutant GBD-gcn5p(KQL) (Fig. 2, left panel, UAS).

FIG. 3.

Enzymatically dead sas3 and gcn5 HAT fusion proteins increase URA3 expression. (A) Mutant GBD-sas3 (C323A)p contains an alanine substitution for cysteine at amino acid 323. (B) Mutant GBD-gcn5(KQL)p contains alanine substitutions for residues KQL at amino acids 124 to 126. Dilution assays were performed as for Fig. 1A. Cells were plated on His− medium to assess cell plating equivalence (left panel, growth) or His− medium containing 5-FOA to assess relative expression levels of the URA3 reporter gene (right panel; URA3 expression).

Most evidence to date supports a correlation between HAT activity and transcriptional activation of genes requiring HAT complex function (reviewed in reference 11). However, in some cases, HAT enzymatic activity is not required for transcription (6, 33, 59). Because several HAT complex components interact with, or participate in, the basal RNA Pol II machinery (42, 71), determinants promoting HAT-independent gene expression may reside in the HAT complexes themselves. Indeed, maximal reporter gene activation by targeted Gcn5p requires Ada2p (16). Although the GBD-gcn5p mutants examined here may retain some residual enzymatic activity in vivo, we considered the alternative possibility that a Gcn5p HAT complex component was contributing to URA3 reporter gene expression.

Multiple subunits of the targeted HAT complex were required for increased gene expression.

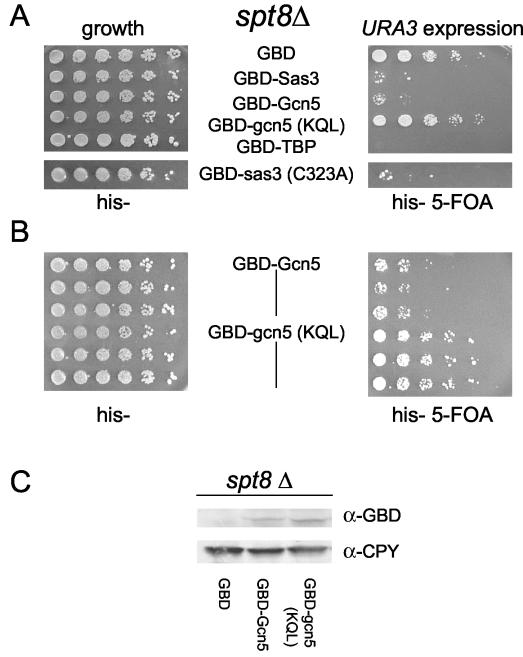

To determine whether tethered HAT-mediated gene expression was dependent on a HAT complex component, we focused on Gcn5p, whose transcriptional properties have been analyzed extensively. To determine if GBD-Gcn5p activation was operating though SAGA or SAGA-related complexes, we assayed URA3 expression in strains harboring chromosomal deletions in components of these Gcn5-containing HAT complexes. Deletion of several genes required for HAT complex integrity or optimal HAT activity revealed that deletion of SPT8, encoding a SAGA component that interacts with TBP (5, 42, 75), was a key factor in expression of the reporter gene. Deletion of SPT8 abrogated URA3 expression to control levels when mutant GBD-gcn5p(KQL) was tethered to the telomere (Fig. 4A, right panel). This observation suggested that GBD-Gcn5p may be operating through SAGA and that a function provided by Spt8p was important for expression. Intriguingly, loss of Spt8p did not affect URA3 expression when wild-type GBD-Gcn5p was targeted to the telomere (Fig. 4A, right panel). Thus, neither loss of enzymatic activity nor loss of Spt8p function individually abrogated URA3 expression. Rather, loss of both was necessary to prevent expression of the URA3 gene, demonstrating collateral activation functions within the SAGA complex.

FIG. 4.

Loss of both HAT enzymatic activity and the SAGA HAT complex component Spt8p is necessary to abolish URA3 expression by Gcn5p. Dilution assays were performed as described for Fig. 1A except with a chromosomal SPT8 deletion strain. TBP, TATA-binding protein. (A) Selective loss of URA3 expression in an spt8Δ strain upon targeting of HAT-dead Gcn5, but not Sas3, fusion proteins. (B) Multiple isolates of GBD-Gcn5p and GBD-gcn5(KQL), denoted as vertical lines, show consistent activation in an spt8Δ strain. (C) In vivo expression levels of GBD-Gcn5p and GBD-gcn5(KQL) fusion proteins in an spt8Δ strain as determined by protein immunoblotting with anti-GBD (α-GBD) antiserum (Santa Cruz Biotech). Anti-CPY (α-CPY) (Molecular Probes) was used as a loading control and is directed towards the yeast carboxypeptidase protein.

The inability of GBD-gcn5(KQL) to increase URA3 expression in an spt8Δ strain was selective in that targeting of the HAT dead GBD-sas3(C323A) protein still resulted in 5-FOA sensitivity (Fig. 4A, right panel), suggesting that loss of Spt8p did not cause a general defect in the transcriptional apparatus. Multiple isolates of GBD-Gcn5p and GBD-gcn5(KQL) were tested and were found to exhibit no detectable variability in URA3 expression (Fig. 4B). Further, the inability of GBD-gcn5(KQL) to increase URA3 expression was not due to decreased stability of the mutant HAT fusion protein in an spt8Δ strain, because comparable amounts of wild-type and mutant GBD-Gcn5p proteins were detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 4C).

The functional overlap of subunits within SAGA has been inferred from genetic and biochemical studies (reviewed in reference 42) where mutations in the Ada class of SAGA proteins (Gcn5, Ada2, and Ada3) or in the Spt class (Spt3p and Spt8p) individually have moderate but distinct phenotypes. However, in combination they exhibit more-severe phenotypes characteristic of mutations in Ada1p, Spt7p, or Spt20p, which disrupt SAGA integrity. We therefore tested whether deletion of SPT3 yielded results similar to that of deletion of SPT8.

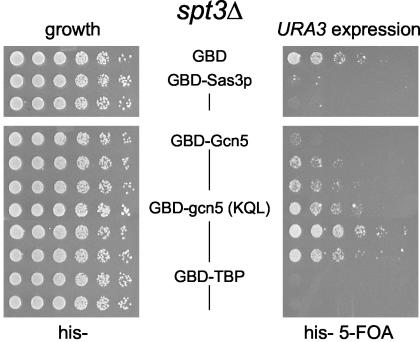

Targeting of Gcn5p and Sas3p in an spt3Δ strain shared several characteristics with that of an spt8Δ strain. GBD-Sas3p and GBD-Gcn5p increased URA3 expression to similar degrees, whereas the GBD-gcn5(KQL) mutant was defective (Fig. 5, right panel). Interestingly, targeting GBD-Gcn5p or GBD-gcn5(KQL) yielded variable URA3 expression (Fig. 5, bottom panel), which was not observed in an spt8Δ strain. This variability correlated with levels of GBD-Gcn5 protein in spt3Δ strains, as determined by immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Deletion of the SAGA component Spt3p causes a HAT-targeting phenotype similar to that of an spt8Δ strain. Dilution assays were performed as for Fig. 1A except with a chromosomal SPT3 deletion strain. Multiple isolates of GBD-Sas3p, GBD-Gcn5p, GBD-gcn5(KQL), and GBD-TBP are shown.

Analyses of SAGA-dependent transcription indicate a key role for Spt8p and Spt3p in TBP interaction (5, 6, 32, 59, 75). Because deletion of SPT3 yielded results similar to those of deletion of SPT8, recruitment of TBP may be a critical event in increased gene transcription mediated by a HAT-containing protein. To test this possibility, TBP was targeted to the URA3 gene in cells in which SPT8 or SPT3 was deleted. GBD-TBP strongly increased URA3 expression in the absence of Spt8p (Fig. 4, right panel) or Spt3p (Fig. 5, right panel), demonstrating that direct recruitment of TBP bypassed the requirement for function of these proteins. This observation is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that direct recruitment of TBP and/or TFIID can promote transcriptional activation in yeast and mammalian cells (30, 86). However, it is noteworthy that here the chimeric HAT or TBP was targeted to the 3′ end of a gene, where its function must be transmitted to the URA3 promoter, more than 1 kb upstream. Such distant activation may occur by altered local chromatin structure or chromosome positioning that permits elevated URA3 expression or by physical association of the targeted fusion proteins with promoter-bound sequence-specific activators through telomere looping (26). Telomere looping may be particularly relevant to TBP-induced activation in this assay, because it would enable direct contact with the promoter-proximal TATA box.

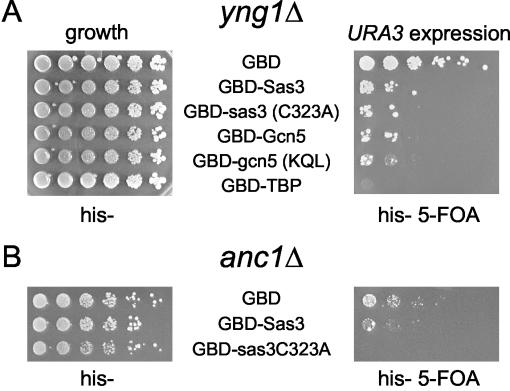

The NuA3 HAT complex subunits Yng1p and Anc1p were not required for GBD-Sas3p-mediated gene expression.

The Sas3p-containing NuA3 complex has been less intensively studied to date than have Gcn5p HAT complexes. To test whether the NuA3 subunits Yng1p or Anc1p perform functions analogous to those of Spt3p and Spt8p in this assay, we expressed GBD-Sas3p in strains bearing mutations in each of these genes. Yng1p is important for transcription of certain target genes in vivo and is postulated to mediate interaction of NuA3 with nucleosomes (45), although no role for interacting with TBP has been established. As shown in Fig. 6A (right panel), deletion of yng1 did not impair URA3 expression by either wild-type or mutant GBD-Sas3p or Gcn5p. Because the GBD-Sas3 HAT fusion proteins are targeted to the telomere via association with the Gal4 UAS, it is not surprising that Yng1p function can be bypassed in this case. Likewise, TBP directly targeted to the telomere was still able to activate in the absence of YNG1 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Deletion of NuA3 HAT complex subunits does not impair the ability of GBD-Sas3p to increase URA3 expression. Dilution assays were performed as for Fig. 1A except with a chromosomal YNG1 (A) or ANC1 (B) deletion strain.

Anc1p is another NuA3 subunit identified through biochemical purification of the HAT complex from yeast. Although Anc1p is also present in RNA Pol II factors (43, 44) and the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (15), its function in NuA3 is unknown. Deletion of anc1 did not impair URA3 expression by GBD-Sas3 or GBD-sas3(C323A) (Fig. 6B, right panel). However, it should be noted that anc1Δ mutants had a modest sensitivity to 5-FOA, and even the GBD control strains grew poorly (Fig. 6B, right panel). Thus, it appears that neither Yng1p nor Anc1p functions analogously to Spt3p and Spt8p in promoting targeted HAT gene expression. As more subunits are identified as bona fide members of the NuA3 HAT complex, as suggested by the mass-spectrophotometric profile of the biochemically purified complex (51), it will be important to test the contributions that these genes make to targeted HAT gene expression.

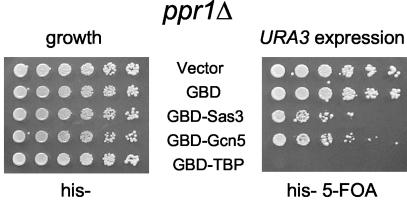

The sequence-specific activator Ppr1p was required for gene expression.

Sequence-specific activators interact with TBP-containing TFIID, as well as with HAT complexes (6, 12, 59, 61, 82). We therefore tested whether targeted HAT-mediated URA3 expression required Ppr1p, the URA3-specific transcription factor. Ppr1p contains an activation domain related to that of Gal4p and is important for transcription of a URA3 gene in a telomeric location (3). Upon HAT targeting in a ppr1Δ strain, URA3 expression was impaired by both GBD-Gcn5p and GBD-Sas3p (Fig. 7, right panel) compared to results with PPR1 strains (Fig. 1A). Gene-specific activators have previously been reported to recruit HAT complexes (reviewed in reference 11). However, in this case the HAT is already targeted to the gene through the GBD. Thus, this observation points to a role for a sequence-specific activator beyond that of simple HAT recruitment.

FIG. 7.

The sequence-specific activator Ppr1p is required for tethered HAT-mediated URA3 expression. Dilution assay was performed as for Fig. 1A, except with a chromosomal PPR1 deletion strain.

Because our previous observations indicated that URA3 expression required Spt8p and Spt3p and because Spt3/Spt8p are known to interact with TBP and in some cases negatively regulate the activation ability of TBP (5), we tested whether TBP directly targeted to the telomere could bypass the requirement for Ppr1p. GBD-TBP increased URA3 expression even in the absence of Ppr1p (Fig. 7, right panel), indicating that TBP recruitment in the context of a HAT complex may need an additional step(s) provided by a sequence-specific activator to promote transcription.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here demonstrate an unexpected plasticity of HAT-mediated gene expression and reveal fundamental molecular requirements for transcription shared by different HATs. The histone acetyltransferases Sas3p and Gcn5p increased gene expression in a context not normally responsive to these HATs (70, 79). Gene expression was not solely dependent on acetyltransferase activity of the targeted HAT. In the case of targeted Gcn5p, either Gcn5p HAT activity or the SAGA HAT complex components Spt8p/Spt3p were required. Because Spt8p and Spt3p are known to interact with TBP (5, 6, 32, 59), and directly targeted TBP was sufficient for URA3 expression in our assay, TBP recruitment is likely to be a critical determinant in HAT-mediated transcription. However, the context of TBP recruitment is important. Directly recruited TBP bypassed the requirement for Ppr1p, whereas TBP presumably recruited in the context of a HAT complex (through Spt8p/Spt3p or other HAT complex components) required the sequence-specific activator. Earlier studies demonstrated that Spt8p associates with TBP to negatively regulate its transcriptional activation function under specific conditions (5). Our observations suggest that a potential activation function provided by Ppr1p may be to alleviate some forms of TBP inhibition, without necessarily altering TBP occupancy.

The mechanism of gene expression we observed shares characteristics with several SAGA-dependent genes. Activation of the HO gene is accomplished through the sequential association of the sequence-specific transcription factor Swi5p, followed by the chromatin-remodeling complex SWI/SNF and SAGA (25). The SAGA-dependent gene GAL1 is also dependent on a sequence-specific activator, Gal4p (6, 59). However, in this case transcription is independent of Gcn5p but dependent on Spt3p (6, 32, 59). ChIP analysis showed that Gal4p recruited SAGA to the GAL1 UAS. In cells in which SPT3 was deleted, SAGA was still recruited to the GAL1 gene (6, 59), but the Pol II preinitiation complex did not form (6) and elevated transcription was abolished (6, 59). A time course analysis of factors associating with the GAL1 gene upon induction further defined the role of SAGA in recruiting TBP, TFIID, and Pol II (14). Upon induction with galactose, SAGA, Mediator, and TFIID sequentially bound the GAL1 gene. Disruption of SAGA by deletion of the HAT complex component SPT20 prevented Pol II binding at the GAL1 gene and blocked activation of the GAL1 gene but did not impair Mediator binding (14). Thus, genetic and biochemical analyses of transcription factor binding at SAGA-dependent genes have established a correlation between Spt3p and TBP recruitment. Our studies suggest that this mechanism may be a common property of HAT-mediated transcriptional regulation.

Elevated expression of the telomeric URA3 reporter gene by targeted Sas3p and Gcn5p also provides mechanistic insight into how boundaries of silenced chromatin may be regulated. Silencing is a form of transcriptional repression that affects regions of the genome in a largely gene-independent manner. Proteins that comprise silenced chromatin include the silent information regulator proteins (Sir1p, Sir2p, Sir3p, Sir4p) and Rap1p (72). Cis-acting sequences have been identified that demarcate transcriptionally active and inactive regions and are termed boundary elements (reviewed in reference 27). These elements were identified by their ability to block the spread of silenced chromatin and often contain gene promoters or require transcription factors for boundary function (7, 8, 28, 29, 37, 38). Of particular relevance is the tRNA gene boundary element to the right of the HMR silence mating-type locus (28). Its boundary activity is weakened upon mutation of the tRNA promoter, Pol III transcription factors TFIIIC and TFIIIB, and the HATs Sas2p and Gcn5p (29). This suggests that Sas2p and Gcn5p participate in restricting the spread of silenced domains.

The importance of chromatin-modifying proteins in boundary function is further supported by the identification of Sas2p, Gcn5p, and other SAGA components in a genetic screen for factors that block the spread of silencing at HMR (66). Likewise, Gcn5p (23, 48) and Esa1p (23) have also been shown to antagonize silencing at the other silenced mating-type locus, HML. One model for boundary function is that factors operating at boundaries actively modify chromatin through posttranslational processes, such as acetylation (27). Two predictions of this model are that HAT-regulated boundaries are hyperacetylated and that they have different nucleosomal structure. Recent evidence has demonstrated extensive hyperacetylation (23, 66) and altered nucleosome patterns (66) at the silenced HM loci upon targeting of specific HATs. Mechanistically, the antisilencing effect these HATs exert may perturb the balance of acetylation, by analogy to competing activities of the HAT Sas2p and the deacetylase Sir2p at the telomere (52, 78), and/or may change the modification state of specific histone residues that regulate binding of silencing proteins (reviewed in reference 49). The ability of targeted Sas3p, Gcn5p, and Sas2p to selectively increase expression of the telomeric URA3 gene in our studies indicates that silenced chromatin near the targeting site can be disrupted upon targeting of these HATs.

Boundaries that define chromosomal domains may arise through diverse mechanisms. Ishii and Laemmli (48) have proposed distinctions among heterochromatic protection activities, which they define as boundary activities (unidirectional disruption of silencing), transcriptional activation, and desilencing activities (bidirectional disruption of silencing). In this context, our studies reveal locus-specific differences in HAT-mediated desilencing activities. We observe that targeted Esa1p does not disrupt silencing at the telomere, whereas this HAT does impair silencing upon targeting to the HML locus (23). Furthermore, we observe that the antisilencing activity of Gcn5p targeted to a telomere does not solely require its HAT enzymatic activity, whereas it does when targeted to HML (23). Differences in HAT requirements in boundary function are reminiscent of differential requirements for SAGA subunits in regulating transcription of euchromatic genes, such as GAL1, HIS3, and INO1. Despite these differences, TBP recruitment may be a convergent function for various HAT complex components.

The molecular dissection presented here is relevant both for understanding principles of transcriptional regulation and for yielding insight into diseases where HAT genes are present as chromosomal translocations (reviewed in reference 50). Many of the chimeric proteins encoded by HAT-containing translocations implicated in human diseases have novel combinations of chromosomal targeting and HAT modules contributed by different genes. This suggests that the aberrantly fused modules may alter normal gene expression through mistargeting of HATs to additional genes or through misregulated chromosomal association and/or function of these HATs at genes where they normally function.

The evolutionary conservation of sequence-specific activators, RNA Pol II basal transcription components, and HAT complex subunits suggests that the observations reported here may provide direction to mammalian experiments aimed at understanding and treating cancers associated with these HAT-containing translocations. For example, MOZ, a human homolog of SAS3, has been identified in patients with acute leukemias as a recurrent translocation partner with different transcriptional coactivators, including CBP, p300, and TIF2 (10, 17, 19, 20, 53, 62). MOZ has also been shown to bind AML1, a key hematopoetic transcription factor, and to activate AML1-dependent genes (54). In parallel with our observations, acetyltransferase activity of MOZ appeared dispensable for AML1-dependent transcription (54). Thus, an important consideration raised by our studies and those of others (21, 54, 60) is that domains besides the HAT motif can play crucial roles in the aberrant function of the chimeric translocation-encoded protein.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Berger, R. Sternglanz, D. Gottschling, D. Rivier, and R. Morse for providing strains and plasmids. We thank J. Heilig, S. Garcia, E. Gamache, F. Solomon, and an anonymous reviewer for comments that improved the manuscript and members of the lab for continuing discussion. S.J. thanks P. M. Dun and E. H. Caddis for technical support.

This work was supported by funding from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allard, S., R. T. Utley, J. Savard, A. Clarke, P. Grant, C. J. Brandl, L. Pillus, J. L. Workman, and J. Cote. 1999. NuA4, an essential transcription adaptor/histone H4 acetyltransferase complex containing Esa1p and the ATM-related cofactor Tra1p. EMBO J. 18:5108-5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio, O. M., B. L. Billington, and D. E. Gottschling. 1991. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66:1279-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aparicio, O. M., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. Overcoming telomeric silencing: a trans-activator competes to establish gene expression in a cell cycle-dependent way. Genes Dev. 8:1133-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlev, N. A., R. Candau, L. Wang, P. Darpino, N. Silverman, and S. L. Berger. 1995. Characterization of physical interactions of the putative transcriptional adaptor, ADA2, with acidic activation domains and TATA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270:19337-19344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belotserkovskaya, R., D. E. Sterner, M. Deng, M. H. Sayre, P. M. Lieberman, and S. L. Berger. 2000. Inhibition of TATA-binding protein function by SAGA subunits Spt3 and Spt8 at Gcn4-activated promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:634-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green. 2001. SAGA is an essential in vivo target of the yeast acidic activator Gal4p. Genes Dev. 15:1935-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bi, X., and J. R. Broach. 1999. UASrpg can function as a heterochromatin boundary element in yeast. Genes Dev. 13:1089-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bi, X. 2002. Domains of gene silencing near the left end of chromosome III in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 160:1401-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeke, J. D., J. Trueheart, G. Natsoulis, and G. R. Fink. 1987. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 154:164-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borrow, J., V. P. Stanton, Jr., J. M. Andresen, R. Becher, F. G. Behm, R. S. Chaganti, C. I. Civin, C. Disteche, I. Dube, A. M. Frischauf, D. Horsman, F. Mitelman, S. Volinia, A. E. Watmore, and D. E. Housman. 1996. The translocation t(8;16)(p11;p13) of acute myeloid leukaemia fuses a putative acetyltransferase to the CREB-binding protein. Nat. Genet. 14:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, C. E., T. Lechner, L. Howe, and J. L. Workman. 2000. The many HATs of transcription coactivators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, C. E., L. Howe, K. Sousa, S. C. Alley, M. J. Carrozza, S. Tan, and J. L. Workman. 2001. Recruitment of HAT complexes by direct activator interactions with the ATM-related Tra1 subunit. Science 292:2333-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brownell, J. E., and C. D. Allis. 1995. An activity gel assay detects a single, catalytically active histone acetyltransferase subunit in Tetrahymena macronuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6364-6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant, G. O., and M. Ptashne. 2003. Independent recruitment in vivo by gal4 of two complexes required for transcription. Mol. Cell 11:1301-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cairns, B. R., N. L. Henry, and R. D. Kornberg. 1996. TFG/TAF30/ANC1, a component of the yeast SWI/SNF complex that is similar to the leukemogenic proteins ENL and AF-9. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3308-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candau, R., J. X. Zhou, C. D. Allis, and S. L. Berger. 1997. Histone acetyltransferase activity and interaction with ADA2 are critical for GCN5 function in vivo. EMBO J. 16:555-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carapeti, M., R. C. Aguiar, J. M. Goldman, and N. C. Cross. 1998. A novel fusion between MOZ and the nuclear receptor coactivator TIF2 in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 91:3127-3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrozza, M. J., R. T. Utley, J. L. Workman, and J. Cote. 2003. The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet. 19:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaffanet, M., M. J. Mozziconacci, F. Fernandez, D. Sainty, M. Lafage-Pochitaloff, D. Birnbaum, and M. J. Pebusque. 1999. A case of inv(8)(p11q24) associated with acute myeloid leukemia involves the MOZ and CBP genes in a masked t(8;16). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 26:161-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaffanet, M., L. Gressin, C. Preudhomme, V. Soenen-Cornu, D. Birnbaum, and M. J. Pebusque. 2000. MOZ is fused to p300 in an acute monocytic leukemia with t(8;22). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 28:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champagne, N., N. Pelletier, and X. J. Yang. 2001. The monocytic leukemia zinc finger protein MOZ is a histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene 20:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chien, C. T., S. Buck, R. Sternglanz, and D. Shore. 1993. Targeting of SIR1 protein establishes transcriptional silencing at HM loci and telomeres in yeast. Cell 75:531-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu, Y. H., Q. Yu, J. J. Sandmeier, and X. Bi. 2003. A targeted histone acetyltransferase can create a sizable region of hyperacetylated chromatin and counteract the propagation of transcriptionally silent chromatin. Genetics 165:115-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke, A. S., J. E. Lowell, S. J. Jacobson, and L. Pillus. 1999. Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2515-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosma, M. P., T. Tanaka, and K. Nasmyth. 1999. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell 97:299-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bruin, D., Z. Zaman, R. A. Liberatore, and M. Ptashne. 2001. Telomere looping permits gene activation by a downstream UAS in yeast. Nature 409:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donze, D., and R. T. Kamakaka. 2002. Braking the silence: how heterochromatic gene repression is stopped in its tracks. Bioessays 24:344-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donze, D., C. R. Adams, J. Rine, and R. T. Kamakaka. 1999. The boundaries of the silenced HMR domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 13:698-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donze, D., and R. T. Kamakaka. 2001. RNA polymerase III and RNA polymerase II promoter complexes are heterochromatin barriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 20:520-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorris, D. R., and K. Struhl. 2000. Artificial recruitment of TFIID, but not RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, activates transcription in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4350-4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyon, Y., W. Selleck, W. S. Lane, S. Tan, and J. Cote. 2004. Structural and functional conservation of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1884-1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudley, A. M., C. Rougeulle, and F. Winston. 1999. The Spt components of SAGA facilitate TBP binding to a promoter at a post-activator-binding step in vivo. Genes Dev. 13:2940-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudley, A. M., L. J. Gansheroff, and F. Winston. 1999. Specific components of the SAGA complex are required for Gcn4- and Gcr1-mediated activation of the his4-912delta promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 151:1365-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisen, A., R. T. Utley, A. Nourani, S. Allard, P. Schmidt, W. S. Lane, J. C. Lucchesi, and C. J. 2001. The yeast NuA4 and Drosophila MSL complexes contain homologous subunits important for transcription regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3484-3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenmann, D. M., K. M. Arndt, S. L. Ricupero, J. W. Rooney, and F. Winston. 1992. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 6:1319-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenmann, D. M., C. Chapon, S. M. Roberts, C. Dollard, and F. Winston. 1994. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT8 gene encodes a very acidic protein that is functionally related to SPT3 and TATA-binding protein. Genetics 137:647-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fourel, G., E. Revardel, C. E. Koering, and E. Gilson. 1999. Cohabitation of insulators and silencing elements in yeast subtelomeric regions. EMBO J. 18:2522-2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fourel, G., C. Boscheron, E. Revardel, E. Lebrun, Y. F. Hu, K. C. Simmen, K. Muller, R. Li, N. Mermod, and E. Gilson. 2001. An activation-independent role of transcription factors in insulator function. EMBO Rep. 2:124-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galarneau, L., A. Nourani, A. A. Boudreault, Y. Zhang, L. Heliot, S. Allard, J. Savard, W. S. Lane, D. J. Stillman, and J. Cote. 2000. Multiple links between the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex and epigenetic control of transcription. Mol. Cell 5:927-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner, K. A., and C. A. Fox. 2001. The Sir1 protein's association with a silenced chromosome domain. Genes Dev. 15:147-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant, P. A., L. Duggan, J. Cote, S. M. Roberts, J. E. Brownell, R. Candau, R. Ohba, T. Owen-Hughes, C. D. Allis, F. Winston, S. L. Berger, and J. L. Workman. 1997. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 11:1640-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant, P. A., D. E. Sterner, L. J. Duggan, J. L. Workman, and S. L. Berger. 1998. The SAGA unfolds: convergence of transcription regulators in chromatin-modifying complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 8:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry, N. L., M. H. Sayre, and R. D. Kornberg. 1992. Purification and characterization of yeast RNA polymerase II general initiation factor g. J. Biol. Chem. 267:23388-23392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henry, N. L., A. M. Campbell, W. J. Feaver, D. Poon, P. A. Weil, and R. D. Kornberg. 1994. TFIIF-TAF-RNA polymerase II connection. Genes Dev. 8:2868-2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howe, L., T. Kusch, N. Muster, R. Chaterji, J. R. Yates III, and J. L. Workman. 2002. Yng1p modulates the activity of Sas3p as a component of the yeast NuA3 histone acetyltransferase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5047-5053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howe, L., D. Auston, P. Grant, S. John, R. G. Cook, J. L. Workman, and L. Pillus. 2001. Histone H3 specific acetyltransferases are essential for cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 15:3144-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikeda, K., D. J. Steger, A. Eberharter, and J. L. Workman. 1999. Activation domain-specific and general transcription stimulation by native histone acetyltransferase complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:855-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishii, K., and U. K. Laemmli. 2003. Structural and dynamic functions establish chromatin domains. Mol. Cell 11:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson, S. J., P. M. Laurenson, and L. Pillus. 2004. Functional analyses of chromatin modifications in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 377:3-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobson, S., and L. Pillus. 1999. Modifying chromatin and concepts of cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.John, S., L. Howe, S. T. Tafrov, P. A. Grant, R. Sternglanz, and J. L. Workman. 2000. The something about silencing protein, Sas3, is the catalytic subunit of NuA3, a yTAF(II)30-containing HAT complex that interacts with the Spt16 subunit of the yeast CP (Cdc68/Pob3)-FACT complex. Genes Dev. 14:1196-1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimura, A., T. Umehara, and M. Horikoshi. 2002. Chromosomal gradient of histone acetylation established by Sas2p and Sir2p functions as a shield against gene silencing. Nat. Genet. 32:370-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitabayashi, I., Y. Aikawa, A. Yokoyama, F. Hosoda, M. Nagai, N. Kakazu, T. Abe, and M. Ohki. 2001. Fusion of MOZ and p300 histone acetyltransferases in acute monocytic leukemia with a t(8;22)(p11;q13) chromosome translocation. Leukemia 15:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitabayashi, I., Y. Aikawa, L. A. Nguyen, A. Yokoyama, and M. Ohki. 2001. Activation of AML1-mediated transcription by MOZ and inhibition by the MOZ-CBP fusion protein. EMBO J. 20:7184-7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kleff, S., E. D. Andrulis, C. W. Anderson, and R. Sternglanz. 1995. Identification of a gene encoding a yeast histone H4 acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24674-24677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krebs, J. E., M. H. Kuo, C. D. Allis, and C. L. Peterson. 1999. Cell cycle-regulated histone acetylation required for expression of the yeast HO gene. Genes Dev. 13:1412-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuo, M. H., J. Zhou, P. Jambeck, M. E. Churchill, and C. D. Allis. 1998. Histone acetyltransferase activity of yeast Gcn5p is required for the activation of target genes in vivo. Genes Dev. 12:627-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuo, M. H., E. vom Baur, K. Struhl, and C. D. Allis. 2000. Gcn4 activator targets Gcn5 histone acetyltransferase to specific promoters independently of transcription. Mol. Cell 6:1309-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larschan, E., and F. Winston. 2001. The S. cerevisiae SAGA complex functions in vivo as a coactivator for transcriptional activation by Gal4. Genes Dev. 15:1946-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lavau, C., C. Du, M. Thirman, and N. Zeleznik-Le. 2000. Chromatin-related properties of CBP fused to MLL generate a myelodysplastic-like syndrome that evolves into myeloid leukemia. EMBO J. 19:4655-4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee, T. I., and R. A. Young. 1998. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes Dev. 12:1398-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liang, J., L. Prouty, B. J. Williams, M. A. Dayton, and K. L. Blanchard. 1998. Acute mixed lineage leukemia with an inv(8)(p11q13) resulting in fusion of the genes for MOZ and TIF2. Blood 92:2118-2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma, J., and M. Ptashne. 1987. Deletion analysis of GAL4 defines two transcriptional activating segments. Cell 48:847-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meijsing, S. H., and A. E. Ehrenhofer-Murray. 2001. The silencing complex SAS-I links histone acetylation to the assembly of repressed chromatin by CAF-I and Asf1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15:3169-3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Narlikar, G. J., H. Y. Fan, and R. E. Kingston. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oki, M., L. Valenzuela, T. Chiba, T. Ito, and R. T. Kamakaka. 2004. Barrier proteins remodel and modify chromatin to restrict silenced domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1956-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parthun, M. R., J. Widom, and D. E. Gottschling. 1996. The major cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase in yeast: links to chromatin replication and histone metabolism. Cell 87:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pray-Grant, M. G., D. Schieltz, S. J. McMahon, J. M. Wood, E. L. Kennedy, R. G. Cook, J. L. Workman, J. R. Yates III, and P. A. Grant. 2002. The novel SLIK histone acetyltransferase complex functions in the yeast retrograde response pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8774-8786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reid, J. L., V. R. Iyer, P. O. Brown, and K. Struhl. 2000. Coordinate regulation of yeast ribosomal protein genes is associated with targeted recruitment of Esa1 histone acetylase. Mol. Cell 6:1297-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reifsnyder, C., J. Lowell, A. Clarke, and L. Pillus. 1996. Yeast SAS silencing genes and human genes associated with AML and HIV-1 Tat interactions are homologous with acetyltransferases. Nat. Genet. 14:42-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roberts, S. M., and F. Winston. 1997. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics 147:451-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rusche, L. N., A. L. Kirchmaier, and J. Rine. 2003. The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:481-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith, E. R., A. Eisen, W. Gu, M. Sattah, A. Pannuti, J. Zhou, R. G. Cook, J. C. Lucchesi, and C. D. Allis. 1998. ESA1 is a histone acetyltransferase that is essential for growth in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3561-3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sterner, D. E., P. A. Grant, S. M. Roberts, L. J. Duggan, R. Belotserkovskaya, L. A. Pacella, F. Winston, J. L. Workman, and S. L. Berger. 1999. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:86-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sterner, D. E., R. Belotserkovskaya, and S. L. Berger. 2002. SALSA, a variant of yeast SAGA, contains truncated Spt7, which correlates with activated transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11622-11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stone, E. M., P. Heun, T. Laroche, L. Pillus, and S. M. Gasser. 2000. MAP kinase signaling induces nuclear reorganization in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 10:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suka, N., K. Luo, and M. Grunstein. 2002. Sir2p and Sas2p opposingly regulate acetylation of yeast histone H4 lysine16 and spreading of heterochromatin. Nat. Genet. 32:378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun, Z. W., and M. Hampsey. 1999. A general requirement for the Sin3-Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex in regulating silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 152:921-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sutton, A., W. J. Shia, D. Band, P. D. Kaufman, S. Osada, J. L. Workman, and R. Sternglanz. 2003. Sas4 and Sas5 are required for the histone acetyltransferase activity of Sas2 in the SAS complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16887-16892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Utley, R. T., and J. Cote. 2003. The MYST family of histone acetyltransferases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 274:203-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Utley, R. T., K. Ikeda, P. A. Grant, J. Cote, D. J. Steger, A. Eberharter, S. John, and J. L. Workman. 1998. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature 394:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Leeuwen, F., and D. E. Gottschling. 2002. Assays for gene silencing in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 350:165-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vogelauer, M., J. Wu, N. Suka, and M. Grunstein. 2000. Global histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature 408:495-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang, L., L. Liu, and S. L. Berger. 1998. Critical residues for histone acetylation by Gcn5, functioning in Ada and SAGA complexes, are also required for transcriptional function in vivo. Genes Dev. 12:640-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xiao, H., J. D. Friesen, and J. T. Lis. 1995. Recruiting TATA-binding protein to a promoter: transcriptional activation without an upstream activator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5757-5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]