Abstract

Telomere stabilization is critical for tumorigenesis. A number of tumors and cell lines use a recombination-based mechanism, alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), to maintain telomere repeat arrays. Current data suggest that the mutation of p53 facilitates the activation of this pathway. In addition to its functions in response to DNA damage, p53 also acts to suppress recombination, independent of transactivation activity, raising the possibility that p53 might regulate the ALT mechanism via its role as a regulator of recombination. To test the role of p53 in ALT we utilized inducible alleles of human p53. We show that expression of transactivation-incompetent p53 inhibits DNA synthesis in ALT cell lines but does not affect telomerase-positive cell lines. The expression of temperature-sensitive p53 in clonal cell lines results in ALT-specific, transactivation-independent growth inhibition, due in part to the perturbation of S phase. Utilizing chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, we demonstrate that p53 is associated with the telomeric complex in ALT cells. Furthermore, the inhibition of DNA synthesis in ALT cells by p53 requires intact specific DNA binding and suppression of recombination functions. We propose that p53 causes transactivation-independent growth inhibition of ALT cells by perturbing telomeric recombination.

Telomeres are specialized structures that confer stability to naturally occurring ends of DNA molecules. Telomere stabilization is critical for the unlimited cellular proliferation that is necessary for tumor formation. While most tumors achieve telomere stabilization through the activation of telomerase (48), a subset of tumors utilize a telomerase-independent mechanism termed alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) to maintain chromosome termini (7, 8). Telomere length in ALT-positive cell lines is highly heterogeneous, with repeats ranging in size from <5 kb to >20 kb (8). A subset of cells in ALT-positive cell lines also contain large multiprotein complexes in which the telomere binding proteins TRF1 and TRF2 and telomeric DNA colocalize with the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear body, termed ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs) (65). The PML nuclear body is a multiprotein nuclear structure that has been implicated in the control of a number of cellular processes including apoptosis (41, 47), leading to the suggestion that cells containing APBs might be targeted to undergo apoptosis. However, APB-positive cells incorporate bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and, thus, are able to carry out DNA replication (22). In addition, the frequency of cells containing APBs is increased when cultures are enriched for cells in the late S phase or G2/M phase of the cell cycle (22, 62), suggesting that the formation of APBs is coordinately regulated with the cell cycle.

Studies carried out with Saccharomyces cerevisiae indicate that telomerase-independent telomere maintenance occurs via a recombination-based mechanism (12, 32, 55). Telomere elongation is RAD52 dependent and may occur through a recombination of either telomeric or subtelomeric repeats. It is likely that a recombination-based mechanism also underlies ALT in mammalian cells. Consistent with this hypothesis, immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that RAD51, RAD52, and the RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 complex colocalize with APBs (65). Studies investigating the fate of a single marked telomere in an ALT-positive cell line also support a recombination-based mechanism (42). In these experiments, rapid changes in the length of the telomere repeat array were observed rather than the gradual changes in size more commonly associated with telomerase activity or telomere loss associated with cell divisions. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that a unique tag embedded in a single telomere will spread to other telomeres in ALT cell lines, leading to the proposal that telomere elongation occurs through intertelomeric gene conversion (17). However, this only occurs when the tag is flanked by telomeric sequences, suggesting that the recombination event occurs within the TTAGGG repeat array. In contrast, the characterization of the telomeric structure in mouse embryonic stem cells deficient in telomerase suggests that recombination may occur within subtelomeric repeats (38).

The mutation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 has been implicated as a contributing factor for ALT activation. Over 80% of the cell lines that use ALT for telomere maintenance are impaired in the p53 pathway, either due to the expression of viral oncoproteins or through a p53 mutation (26). In one study, all 10 of the cell lines derived from breast fibroblasts of an individual with Li Fraumeni syndrome, carrying a germ line mutation in p53, used ALT for telomere maintenance (8). Similarly, the expression of dominant-negative p53 in conjunction with the overexpression of cyclin D1 yielded an ALT-positive immortal cell line (39). Finally, it has recently been reported that ovarian tumors harboring p53 null mutations are more likely to be telomerase negative (50), although it was not established in this study how many of these tumors exhibited the ultralong telomeres and APBs that are characteristic of ALT. While these data suggest that p53 mutation provides a permissive environment for the activation of the ALT pathway of telomere maintenance, it must be pointed out that the majority of p53-compromised cell lines and tumors use telomerase to achieve telomere stabilization. Thus, mutation of the p53 pathway is not sufficient for ALT activation but may be one of several required changes.

Interestingly, from the standpoint of recombination at telomeres, p53 has been found to suppress recombination in vivo. For example, cell lines expressing mutant p53 have increased rates of homologous recombination (3, 34, 58). Likewise, the expression of p53 can inhibit the generation of a recombinant chromosome derived from related simian virus 40 (SV40) chromosomes in cell culture (16, 57). p53 also interacts physically with RAD51 and RecA, inhibiting their function (53), and has been found to bind to Holliday junctions and facilitate cleavage of these structures by the Holliday junction resolvases T4 endonuclease VII and T7 endonuclease I in vitro (29). The suppression of recombination by p53 does not require its transactivation function (4, 15, 59), suggesting that p53 exerts its effect on recombination independent of changes in gene expression. Because present evidence indicates that ALT involves telomeric recombination, that loss of p53 function is correlated with activation of ALT, and that p53 is involved in suppressing recombination, we sought to determine the role of p53 in the regulation of ALT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, constructs, and transfection conditions.

HIO107, HIO80, HIO120, and HIO114 human ovarian surface epithelium cell lines (1), derived from four different individuals, were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of Media 199 and MCDB-105 medium supplemented with 4% fetal bovine serum and 0.2 IU of pork insulin (Lilly) per ml. The mesothelioma 6 (Meso6) cell line (19) was maintained in RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. The Wi38VA13/RA2 embryonic lung fibroblast cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Temperature-sensitive alleles of p53 (ts-p53) have been described in detail previously. Temperature sensitivity is conferred by a well-characterized mutation of alanine to valine at position 138 (33, 35). The loss of transactivation function was achieved by mutating amino acid 22 from leucine to serine and amino acid 23 from tryptophan to glutamine, resulting in p53(22/23) (31). Both alleles of p53 are inactive when cells are cultured at 39°C and are active when cells are cultured at 32°C. The R273H, R248Q, and R175H mutations were introduced into the p53(22/23) allele by using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the primer pairs R273H-F, 5′CAGCTTTGAGGTGCATGTTTGTGCCTGTCC, and R273H-R 5′GGACAGGCACAAACATGCACCTCAAAGCTG; R248Q-F, 5′GGCGGCATGAACCAGAGGCCCATCCTC, and R248Q-R 5′GAGGATGGGCCTCTGGTTCATGCCGCC; and R175H-F, 5′GGAGGTTGTGAGGCACTGCCCCCACCATG, and R175H-R, 5′CATGGTGGGGGCAGTGCCTCACAACCTCC, respectively, as recommended by the manufacturer. The incorporation of the point mutation was confirmed by sequencing. To generate stable lines that express temperature-sensitive wild-type or transactivation-incompetent p53 in HIO107 and HIO114, cells were transfected by electroporation by using a Gene Pulsar II apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 280 V and 975 μF. For transient transfections, all of the above cell lines were treated with FUGENE 6 reagent (Roche) as recommended by the manufacturer. The cells were subcultured directly onto coverslips 24 h posttransfection and allowed to recover overnight at 39°C. For BrdU analysis, cultures were grown at 39 or 32°C for the 48 h prior to pulsing with 10 μM BrdU for either 40 min or 24 h.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Cells were grown directly on coverslips and processed for immunofluorescence as described previously (22). The detection of APBs was carried out by using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (FC-08 [22]) raised against a peptide contained in the amino terminal domain of hTRF2 diluted 1:200 and a goat polyclonal antibody against the N terminus of PML (N-19; Santa Cruz) diluted 1:5,000.

Detection of BrdU incorporation was carried out by using a BrdU labeling and detection kit I (Roche) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The cells were harvested immediately after BrdU exposure. p53 was detected by using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (FL-393; Santa Cruz) diluted 1:20,000. BrdU was detected by using a mouse monoclonal antibody (diluted 1:50) provided by the manufacturer (Roche). For each cell line, at least 50 cells were scored.

Primary antibodies were detected by using tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The secondary antibodies did not cross-react. Following incubation with secondary antibodies, the DNA was stained with 0.2 μg of DAPI (4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) per ml.

Western blot analysis.

Protein lysates were prepared by solubilizing 5 × 103 cells in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) per μl. Protein from 2 × 104 cells were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels per lane. Proteins were detected by using the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antibody against p53 (FL-393; Santa Cruz), mouse monoclonal antibody against p21WAF1 (F-5; Santa Cruz), and mouse monoclonal antibody against SV40 large T antigen (T-Ag) (Pab108; Santa Cruz). Secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody raised in donkey against rabbit IgG and sheep against mouse IgG (Amersham Pharmacia) and were detected by either an ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia) or SuperSignal West Dura (Pierce).

Viability and apoptosis assay.

Viable and apoptotic cells were quantitated by using a Guava personal cytometer and the Guava ViaCount Reagent or the Guava Nexin Kit, respectively, following the manufacturer's specifications. Cells were incubated at 39 or 32°C and harvested every 24 h for up to 96 h. For viability, cells were stained with the ViaCount Reagent. Apoptotic cells were detected by staining with annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7 AAD) by using the Guava Nexin kit. Both early apoptotic (annexin V-positive) and late apoptotic (annexin V- and 7 AAD-positive) cells were included in the analysis.

FACS analysis.

For hydroxyurea (HU) arrests, cells were exposed to 1 mM HU for 22 h prior to harvesting for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. For BrdU analysis, cells were pulsed with 10 μM BrdU for 40 min just prior to harvest. Cells were collected by trypsinization, washed twice with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-2 mM EDTA and fixed in cold 70% ethanol. Following fixation, the DNA was denatured by exposure to 2 M HCl-0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. The acid was then neutralized with 0.1 M sodium borate, and BrdU was detected by incubating for 30 min at room temperature with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-BrdU (Becton Dickinson). DNA was detected by staining with propidium iodide (50 mg/ml). For dual analysis of BrdU and CD19, the cells were transiently cotransfected with CD19 (37) in conjunction with either a vector or ts-p53TA by using FUGENE 6 reagent, subcultured 24 h posttransfection, and allowed to recover for 4 to 5 h at 39°C. The cells were then shifted to 32°C for an additional 48 h prior to pulsing with 10 μM BrdU for 40 min. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with 1× PBS-0.1% bovine serum albumin-0.02% sodium azide, incubated with phycoerytherin-conjugated anti-CD19 (Becton Dickinson) for 1 h at 4°C, and fixed in cold 70% ethanol. After at least 12 h of fixation at 4°C in the dark, the cells were incubated with 1% paraformaldehyde-0.01% Tween 20 in PBS for 30 min, followed by treatment with DNase I for 10 min at room temperature. BrdU was detected by incubating the cells for 30 min at room temperature with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-BrdU (Becton Dickinson). For all analyses, the cells were analyzed by using a Becton-Dickinson FACScan and FlowJo Software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was carried out using the ChIP assay reagents (Upstate Biotechnology Laboratories) essentially as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 1 × 107 cells were cross-linked for 10 min at room temperature by the addition of formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%. The reaction was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Nuclei were isolated, and the chromatin was sonicated 10 times for 10 s each time by using a 2-mm tip and 60% power to generate fragments averaging 1 to 2 kb. GammaBind Plus Sepharose beads (Amershsam) were incubated with the chromatin for 1 h at 4°C to preclear the chromatin. The precleared chromatin was incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: goat polyclonal human TRF2 (Imgenex), goat polyclonal p53 (C-19; Santa Cruz), or goat serum IgG (Santa Cruz). Immune complexes were collected on GammaBind Plus Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4°C. Following washes, the immune complex was eluted from the beads as described by the manufacturer. Cross-linking was reversed by incubation in 0.2 M NaCl for 6 h at 60°C. The resulting DNA was purified by treatment with proteinase K, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. The DNA was resuspended in water, and one-half of the sample was interrogated by slot blot hybridization by using oligonucleotides complementary to the telomeric repeats as described previously (5). The filter was stripped and reprobed to detect centromeric alpha satellite (36) as described previously (2). One-quarter of the sample was interrogated by PCR to detect the p53 binding site at position −1.4 kb within the p21WAF1 promoter by using the primers 5′ACAGCAGAGGAGAAAGAAGCC3′ and 5′ATTACTGACATCTCAGGCTGC3′. PCR was carried out under standard conditions (a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1× Taq buffer, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase) for 40 cycles at an annealing temperature of 61°C to generate a 113-bp product spanning positions −1348 to −1461 of the p21WAF1 promoter (GenBank accession number U24170).

RESULTS

p53 inhibits DNA replication in cell lines that use ALT for telomere maintenance.

To determine if p53 inhibits the growth of ALT cells, we made use of four ALT cell lines. Three of these were derived from human ovarian surface epithelium from independent individuals (HIO80, HIO107, and HIO120) (1, 22), and the fourth cell line, WI38-VA13/2RA was derived from fetal human lung fibroblasts. In addition, three telomerase-positive cell lines were used. The first is from a human ovarian surface epithelium cell line derived from a fourth individual (HIO114), the second is derived from a mesothelioma (Meso6[19]), and the third is a HeLa cell line. All the HIO cell lines and WI38-VA13 were immortalized with SV40 and contain large T-Ag. Large T-Ag binds to and sequesters p53, preventing it from responding to DNA damage and rendering cells containing this viral oncoprotein null for the p53 pathway. The Meso6 cell line is derived from a malignant mesothelioma and also contains SV40 (19). Finally, in HeLa cells p53 is inactivated by human papillomavirus E6/E7.

The cell lines were transiently transfected with a temperature-sensitive allele of human p53 (ts-p53) containing a mutation in the transactivation domain that impairs the ability of p53 to confer growth arrest or apoptosis in response to DNA damage (27, 31, 44). At 39°C, this transactivation-incompetent allele (ts-p53TA) is in mutant conformation and unable to bind specifically to DNA (33, 35). At 32°C, ts-p53TA is in a wild-type conformation and is able to bind to p53 target sequences. It should be noted that at both 39 and 32°C ts-p53 alleles retain nonspecific DNA binding activity (30, 63), and so phenotypes observed only at 32°C require the specific DNA binding activity of p53.

To quantitate the level of proliferation, the nucleotide analog BrdU was added to transfected cells for the final 40 min of culture in order to label cells in S phase. Indirect immunofluorescence was carried out to detect p53 and BrdU (Fig. 1A). Due to the presence of large T-Ag, all the cells in each culture contain stabilized p53. However, under the staining conditions used here, only the transfected cells overexpressing p53 were positive and were scored (Fig. 1A). Because p53 is overexpressed, the protein is often present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. The frequency of cells with high levels of p53 (i.e., that were expressing the exogenous p53 allele) that were also BrdU positive was determined for each cell line at 39 and at 32°C (Fig 1B, ts-p53TA+). The effect of the different culture temperatures was controlled for by scoring the difference in the frequency of BrdU-positive cells transfected with empty vector at the two temperatures (Fig. 1B, vector). A ratio of BrdU-positive cells at the two temperatures was then generated, where a value of 1 indicates no difference in the amount of BrdU incorporation when cells are cultured at the two temperatures. The ratio of BrdU incorporation at the two temperatures in cells transfected with the empty vector ranged from 0.4 in the Meso6 cell line (telomerase positive) to 0.9 in the HIO120 cell line (ALT positive), indicating that cell growth was inhibited at 32°C to various extents in the different cell backgrounds (Fig. 1B). The expression of ts-p53TA at the active temperature of 32°C reduced the frequency of BrdU-positive cells in all ALT cell lines tested relative to the ratio generated from cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 1B), indicating that the expression of ts-p53TA inhibits DNA replication beyond the effects induced by culturing at a lower temperature. In contrast, the expression of ts-p53TA did not have an inhibitory effect on BrdU incorporation in the telomerase-positive cell lines. There was either a similar ratio of BrdU incorporation in cells transfected with ts-p53TA compared to the vector or a higher frequency of BrdU-positive cells when ts-p53TA was expressed.

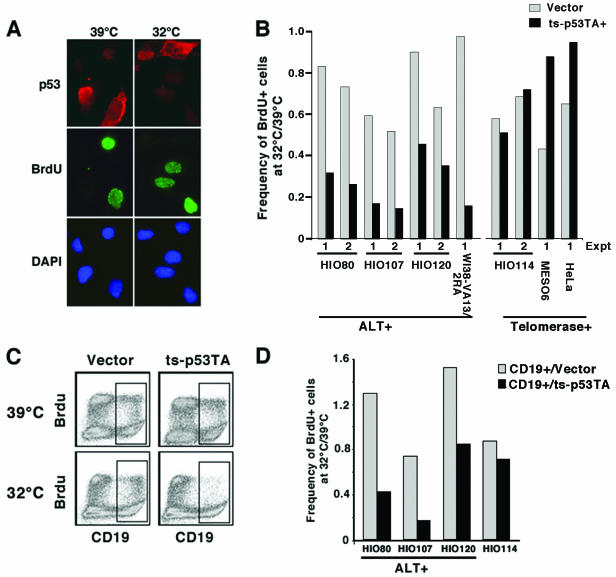

FIG. 1.

Expression of ts-p53TA inhibits DNA replication in ALT cell lines. (A) HIO107 cells transiently transfected with ts-p53TA were cultured at either 39 or 32°C for 48 h, pulsed for 40 min with BrdU, and then harvested to detect p53 (red) and BrdU (green). DNA was detected with DAPI. Note that the ts-p53TA-positive cells cultured at 32°C have not incorporated BrdU. Due to overexpression of p53, the protein may be present in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. (B) Quantitation of data such as those shown in panel A generated from the indicated cell lines. The ALT cell lines expressing ts-p53TA have a reduced frequency of BrdU-positive cells when cultured at 32°C compared to the frequency of BrdU-positive cells transfected with empty vector. (C) FACS analysis of HIO107 cells cotransfected with the CD19 cell surface marker and ts-p53TA. Cells were cultured and pulsed with BrdU as in panel A and then stained to detect BrdU (y axis) and CD19 (x axis). (D) Quantitation of data such as those shown in panel C for the indicated cell lines. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells in the transfected population is determined by gating on the CD19-positive population. The expression of ts-p53TA does not inhibit BrdU incorporation at 32°C in the telomerase-positive cell lines relative to cells transfected with empty vector in either assay.

To assess the inhibition of DNA replication in an independent assay, cells were cotransfected with ts-p53TA and the cell surface marker CD19 (37). Following culture as above, cells were harvested for FACS analysis and stained for BrdU incorporation and CD19 expression. Transfected cells were identified based upon being CD19 positive, and the frequency of BrdU-positive cells in this population at either 39 or 32°C was determined (Fig. 1C and 1D). Again, the cell lines were variably sensitive to growth at 32°C as demonstrated by transfection with empty vector, and the expression of ts-p53TA inhibited DNA replication specifically in the ALT cell lines. Together, these data indicate that p53 inhibits cellular proliferation, as measured by decreased DNA replication, in a transactivation-independent manner specifically in ALT cell lines.

Transactivation-incompetent p53 inhibits growth of cell lines that use ALT for telomere maintenance.

To further define the growth inhibitory role of p53 in ALT cells, we generated clonal cell lines that express similar levels of temperature-sensitive human p53 protein (ts-p53WT) or ts-p53TA protein in the HIO107 ALT and HIO114 telomerase-positive parental backgrounds. Both the HIO107 and HIO114 cell lines retain wild-type p53 (A.K. Godwin, unpublished data) which is inactivated by the presence of large T-Ag. The expression levels of p53 are increased in the p53 clonal cell lines relative to the parental cell lines (Fig. 2A and data not shown). This increase in the expression of p53 is sufficient to activate cellular responses, because cells expressing ts-p53WT accumulate p21WAF1 protein, a p53-responsive gene, when cultured at 32°C (Fig. 2A). In contrast, p21WAF1 does not accumulate in the cell lines expressing ts-p53TA, despite a similar increase in the level of p53 protein relative to the parental cell lines. None of the cell lines accumulated significant levels of p21WAF1 at 39°C, when both p53 proteins are in mutant conformation. The lack of p21WAF1 accumulation in the cell lines expressing the ts-p53TA allele also indicates that significant levels of the endogenous wild-type p53 are not released from large T-Ag in the presence of the exogenously expressed p53. As expected, expression of ts-p53WT at 32°C resulted in increased levels of apoptosis over 72 h (Fig. 2B). The difference in the relative levels of apoptosis following the expression of ts-p53WT in the HIO107 and HIO114 cell lines is due to an approximate twofold higher level of background apoptosis in the HIO114 cells. The increased apoptosis that occurs following the expression of ts-p53WT at 32°C can be attributed to active p53 as it is not observed when either cell line is grown at 39°C and is not observed at either temperature in the parental cell lines. Consistent with previous reports (43, 44), apoptosis is impaired in both the HIO107-TA and HIO114-TA cell lines relative to the cell lines expressing ts-p53WT (Fig. 2B).

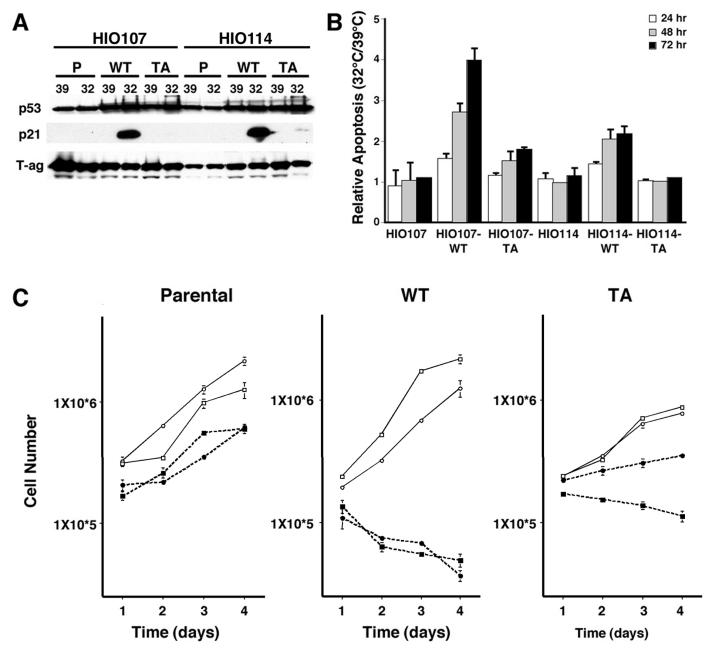

FIG. 2.

Characterization of ALT-positive HIO107 or telomerase-positive HIO114 cell lines expressing either wild-type (WT) or transactivation-incompetent (TA) p53. (A) Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts from the indicated cell lines prepared after 48 h of growth at 39 or 32°C probed to detect p53, p21WAF1, and T-Ag as a loading control. p53-TA does not result in accumulation of p21WAF1 protein. P, parental cell line. (B) Frequency of apoptotic cells, detected by 7 AAD and annexin V staining, in the indicated cell lines. Results are shown as the increase (n-fold) in apoptosis when cells are cultured at 32°C compared to the level of background apoptosis in the culture at 39°C. Relative to ts-p53WT, the ts-p53TA allele is impaired in its ability to induce apoptosis at the permissive temperature of 32°C. (C) Growth curves of the HIO107 ALT (squares) or HIO114 telomerase-positive (circles) derived cell lines at 39°C (open symbols; solid line) or 32°C (filled symbols; dashed line). Expression of p53-TA causes growth inhibition in the HIO107 ALT background. The results are the summary of experiments done in triplicate. Where they are not visible, the standard error bars are below the resolution of the graph.

The effects of p53 expression on cell growth were assessed. The HIO107 ALT and HIO114 telomerase-positive parental cell lines proliferate at both temperatures, although growth is slower at 32 than at 39°C. As expected, the expression of ts-p53WT in either the HIO107 or the HIO114 cell line causes cell death (Fig. 2C). The HIO107-TA ALT cell line also exhibited growth inhibition at 32°C (Fig. 2C), while the HIO114-TA telomerase-positive cell line continued to proliferate. Similar results were obtained with other independent clones of HIO107 and HIO114 expressing ts-p53WT and ts-p53TA (data not shown). These data suggest that p53 specifically inhibits the growth of ALT cells through a transactivation-independent mechanism.

The inhibition of DNA replication occurs rapidly after the expression of ts-p53TA at 32°C. Thus, this phenotype is unlikely to rely upon the gradual telomere attrition that is associated with cellular division in the absence of a mechanism to replicate chromosome termini. However, to establish if expression of the p53 alleles induced rapid alterations in telomeric structure, we carried out an analysis of terminal restriction fragments. No change in telomere length or in the G-strand overhang was detectable in the HIO107-TA cell line when cultured at 32°C compared to results at 39°C (data not shown). These data indicate that the growth inhibition caused by the ts-p53TA allele is also not due to rapidly occurring global alterations in telomere structure. However, because cellular responses may be triggered by a few dysfunctional telomeres (14, 25), it is unlikely that changes involving a minority of telomeres would be detected.

p53 increases the frequency of ALT-associated PML nuclear bodies.

To determine if the expression of p53 had an effect on the ALT pathway, we analyzed the frequency of APBs in which telomeric DNA and proteins colocalize with the PML nuclear body (65). APB-positive cells increase in frequency in both the HIO107-WT and HIO107-TA cell lines when cells are cultured at 32°C, relative to the frequency of APB-positive cells at 39°C (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in the parental HIO107 cell line, cells containing APBs are slightly more frequent at 39°C, suggesting that the increased frequency of APB-containing cells at 32°C is a consequence of the introduced p53 alleles. Further, these results indicate that the increase in APB-positive cells does not require the transactivation activity of p53. It has previously been demonstrated that APBs are cell cycle regulated, accumulating in cells in the late S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle (22, 62). The increase in APB-positive cells at 32°C suggests that the expression of ts-p53TA may perturb the cell cycle in cells that use ALT for telomere maintenance.

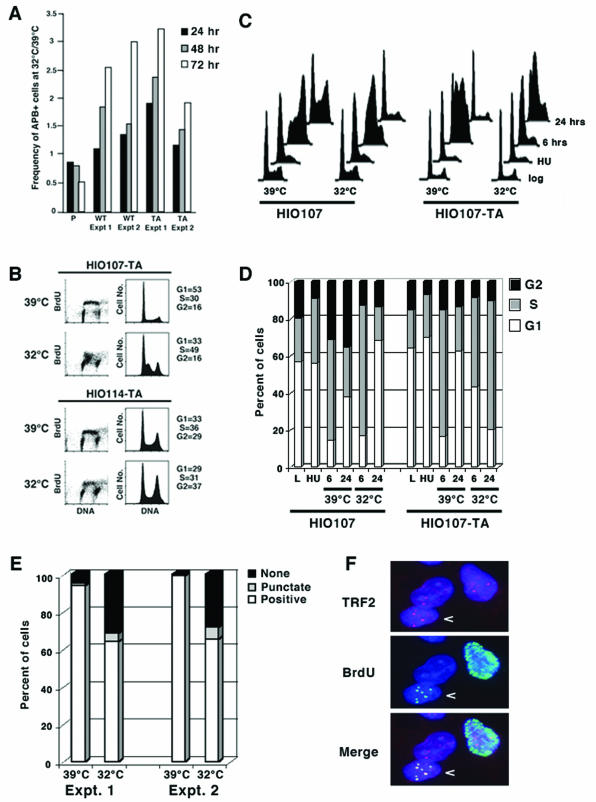

FIG. 3.

Expression of ts-p53TA perturbs APB frequency and causes an S phase delay in HIO107 ALT cells. (A) The frequency of APB-positive cells is increased two- to threefold when cell lines expressing either ts-p53WT or ts-p53TA are cultured at 32°C. APBs were detected by costaining the cells with a goat polyclonal antibody against PML and a rabbit polyclonal antibody (FC-08) against TRF2. (B) The HIO107-TA ALT cell line incorporates BrdU, but the cells accumulate in early S phase after 72 h at 32°C, while the HIO114 cell line is unaffected by growth at 32°C. The left panel shows a FACS analysis of BrdU intensity (y axis) versus DNA content (x axis). The right panel shows the cell cycle profiles generated from the data on the left of the figure (y axis, number of events; x axis, DNA content). (C) The parental HIO107 and the HIO107-TA cell lines were arrested by exposure to HU and, following release, cultured at either 32 or 39°C for the indicated time prior to harvest. The presence of active ts-p53TA prevents cells from progressing through S phase following the removal of HU. y axis, number of events; x axis, DNA content. (D) Quantitation of the cell cycle distribution of the populations shown in panel C. HIO107-TA cells accumulate in S phase for up to 24 h, suggesting that S phase is delayed when ts-p53TA is expressed. (E) Quantitation of the pattern of BrdU incorporation in HIO107-TA cells after 72 h of growth at 32°C. The majority of the cells are BrdU positive at 39°C, while at 32°C many of the cells are either BrdU negative or have punctate BrdU staining. (F) At 32°C, some HIO107-TA cells exhibit punctate BrdU staining which colocalizes with the telomeric protein TRF2 (arrow). The other two staining patterns also shown are diffuse nuclear staining or no BrdU incorporation.

p53 causes an S phase delay in cells that use ALT for telomere maintenance.

To determine if the expression of p53-TA altered cell cycle progression in ALT cells relative to telomerase-positive cells, asynchronous cultures of the HIO107-TA and the HIO114-TA cell lines were pulsed with BrdU after 72 h of growth at either 32 or 39°C, followed by simultaneous detection of BrdU and DNA content and FACS analysis. Both the HIO107-TA ALT and the HIO114-TA telomerase-positive cell lines incorporated BrdU throughout S phase at 39°C (Fig. 3B), consistent with their normal growth at this temperature (Fig. 2C). The presence of active p53-TA, i.e., when cells are grown at 32°C, had no effect on BrdU incorporation in the HIO114-TA cell line, which is consistent with the continued incorporation in transiently transfected populations (Fig. 1) and with the continued proliferation at 32°C in clonal cell lines that stably express this allele (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the BrdU-positive cells in the HIO107-TA cell line at 32°C are concentrated in early S phase (Fig. 3B), suggesting that p53 causes a transactivation-independent delay of normal S phase progression specifically in ALT cells.

To further investigate this ALT-specific effect on S phase, the HIO107-TA cell line was arrested in early S phase with HU and then cultured at either 32 or 39°C following the removal of drug. Because the expression of ts-p53TA does not perturb cell cycle progression in the telomerase-positive HIO114 cells (Fig. 3B), they were not assessed here. The HIO107 parental cell line progresses through the cell cycle at both temperatures following the removal of HU (Fig. 3C). Likewise, HIO107-TA cells arrest efficiently and at 39°C, when ts-p53TA is inactive, progress through the cell cycle normally after the removal of HU. In contrast, HIO107-TA cells do not progress through the cell cycle at 32°C following the removal of HU and instead appear to be trapped in early S phase (Fig. 3C). A similar S phase delay is observed in the HIO107-WT cell line (data not shown). Quantitation of the FACS data indicates that HIO107-TA cells cultured at 32°C continue to accumulate in S phase for at least 24 h following the removal of HU (Fig. 3D). BrdU labeling for 40 min prior to harvest indicates that HIO107-TA cells are replicating DNA at 32°C at every time point, albeit to a much reduced extent (data not shown). Thus, the HIO107-TA cells are not arrested in S phase but instead exhibit a delayed progression with reduced DNA replication as measured by BrdU incorporation. These data confirm that p53 causes a transactivation-independent S phase delay in ALT cells.

To directly visualize the DNA replication that occurs during the S phase delay in HIO107-TA cells, cultures were grown for 48 h at either 39 or 32°C and then for an additional 24 h in the presence of BrdU. The frequency of cells that incorporated BrdU was scored in at least 100 cells for each culture. At 39°C, >90% of the cells incorporated high levels of BrdU, defined as total nuclear staining (Fig. 3E). In contrast, at 32°C approximately 65% of the HIO107-TA cells incorporated high levels of BrdU (Fig. 3E). A large fraction of cells at 32°C, approximately 30%, did not incorporate any BrdU. In addition, in approximately 5% of the cells cultured at 32°C, BrdU incorporation was punctate with the BrdU colocalizing with TRF2 and TRF1 at APBs (Fig. 3E and F and data not shown). This pattern was extremely rare at 39°C, occurring in <1% of the cells. BrdU incorporation at APBs has been noted previously and has been suggested to represent replication of ALT telomeres (61). These data suggest that some of the continued BrdU incorporation observed in the S phase-delayed populations is occurring at, or near, telomeric DNA.

p53 associates with the telomeric complex in cells that use ALT for telomere maintenance.

It has been reported that p53 binds to telomeric DNA in vitro (51). If the ts-p53TA allele used here is exerting its growth inhibitory effect by preventing telomeric recombination, then we might predict an association between p53 and the telomeric complex. To determine if p53 is able to directly interact with telomeres, we utilized ChIP assays. As a positive control, ChIP assays were carried out by using the constitutive telomere binding protein TRF2 (6) (Fig. 4A). Immunoprecipitation is dependent upon TRF2 antibody and requires protein-DNA cross-linking with formaldehyde. Similar results were obtained with an antibody against the telomeric binding protein TRF1 (data not shown). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation is specific for telomeric DNA because there is no detectable hybridization when the same filter is hybridized with probes directed against centromeric α-satellite sequences (Fig. 4A). We found that p53 is associated with the telomeric complex in the HIO107-TA cell line but only when p53 is in an active conformation, i.e., when the cells are cultured at 32°C (Fig. 4A). The enrichment in telomeric DNA precipitated at 32°C by antibodies against p53 is paralleled by a similar level of enrichment in α-satellite sequences (4.6% of input), suggesting that when p53 is competent to bind to DNA, it is located at numerous sites in the genome. Quantitation of the amount of telomeric DNA precipitated is shown in Fig. 4B.

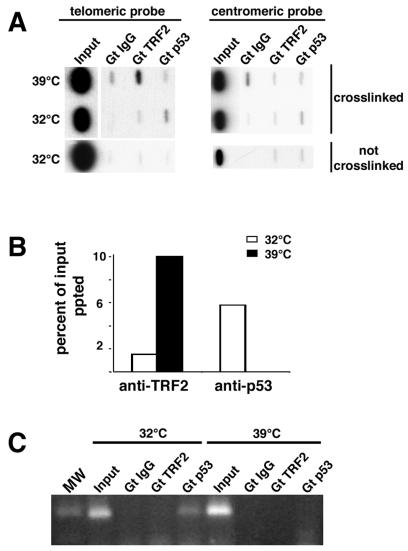

FIG. 4.

ChIP analysis. (A) Telomeric DNA is precipitated by antibodies against the telomeric binding proteins TRF2 but not by nonspecific goat IgG, irrespective of culture conditions. Immunoprecipitation requires formaldehyde cross-linking of proteins to DNA. p53 is also associated with telomeric DNA in the HIO107-TA cell line but only at the permissive temperature of 32°C. Antibodies against TRF2 do not immunoprecipitate centromeric α-satellite sequences. (B) Quantitation of the data shown in panel A. Percent input precipitated (ppted) = [(signal strength of telomeric DNA precipitated with the indicated specific antibody − background signal obtained with nonspecific IgG)/input signal] × 100. (C) Agarose gel of PCR products using primers to amplify the p53 binding site at position −1.4 kb within the p21WAF1 promoter. The template DNAs are identical to those interrogated for the experiment shown in panel C. The predicted product of 113 bp is only detected in DNA from the ChIP assay carried out with an antibody against p53 at 32°C. MW, PhiX HaeIII markers. Antibodies used for all panels are as follows: Gt TRF2, goat polyclonal antibody against TRF2 (Imgenex); Gt p53, goat polyclonal antibody against the carboxy terminus of human p53 (C-19; Santa Cruz); Gt IgG, goat IgG (Santa Cruz).

To confirm that the antibody against p53 was precipitating known p53-associated DNA sequences, a proportion of the immunoprecipitated DNA was interrogated by PCR for the presence of the p21WAF1 promoter. As expected, the region of the p21WAF1 promoter encompassing the p53 binding site at position −1.4 kb (18) was precipitated by the antibody against p53 in both cell lines at 32°C (Fig. 4D), but not by nonspecific rabbit IgG, goat IgG, or anti-TRF2.

Growth suppression of ALT cells by p53 requires intact suppression of recombination function.

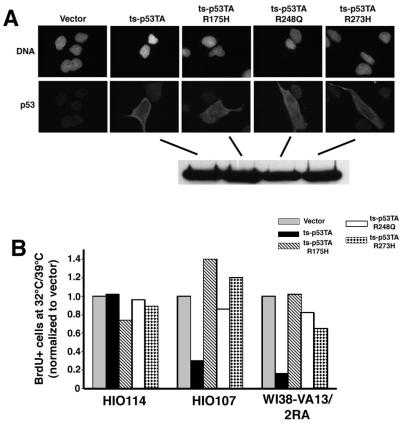

p53 is able to bind to Holliday junctions (29) in vitro and, through interactions with the BLM and WRN proteins, may contribute to the suppression of inappropriate recombination (64). To directly test if the transactivation-independent, ALT-specific growth inhibition is due to interference with recombination-based telomere maintenance, we introduced into the ts-p53TA plasmid the R175H, R248Q, and R273H mutations, which compromise the specific DNA binding and suppression of recombination functions of p53 (3, 13, 15, 45, 60). While some p53 mutations have been reported to have gain-of-function activities, a functional transactivation domain appears to be essential for this phenotype (9, 49) and, thus, would be eliminated in the ts-p53TA mutant background. Because the mutations that impair suppression of the recombination function fall within the DNA binding domain of p53, these mutants are unable to associate with p53 target sequences (13, 60). HIO107 ALT and HIO114 telomerase-positive cells were transiently transfected with these compound mutant alleles and analyzed as shown in Fig. 1. Again, only those cells with high levels of p53, therefore expressing the ectopic allele, were scored (Fig. 5A, top). Furthermore, Western blot analysis indicated that all mutant proteins are stable (Fig. 5A, bottom). As shown previously, the expression of ts-p53TA inhibits BrdU incorporation at 32°C in the HIO107 and WI38-VA13/2RA ALT cell lines but not in the telomerase-positive HIO114 cell line. The introduction of any of the compound mutants had no effect in the telomerase-positive HIO114 cell line, with BrdU incorporation occurring at a level similar to that seen with the ts-p53TA allele. However, the expression of the ts-p53TAR175H, ts-p53TA-R248Q, or ts-p53TA-R273 allele in either the HIO107 or the WI38-VA13/2RA ALT cell lines suppressed the inhibition of BrdU incorporation (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the transactivation-independent, ALT-specific inhibition of DNA replication caused by p53 requires the specific DNA binding and suppression of the recombination functions of p53.

FIG. 5.

Expression of p53 mutant alleles that compromise the ability of p53 to suppress recombination does not inhibit DNA replication in ALT cell lines. (A) Immunofluorescent staining of the indicated p53 compound mutant protein (top). DNA was stained with DAPI. Western analysis of each p53 compound mutant allele is shown (bottom). (B) Ratio of BrdU incorporation in transfected cells at 39 versus 32°C for the HIO107 and WI38-VA13/2RA ALT-positive and HIO114 telomerase-positive cell lines transfected with empty vector or the indicated p53 allele. All ratios were normalized to the frequency of BrdU incorporation at the two temperatures in control cells transfected with empty vector in parallel.

DISCUSSION

Present evidence suggests that ALT is a recombination-based mechanism (17) and that the mutation of p53 provides a permissive environment for the activation of this telomere maintenance pathway (8, 39, 50). Because p53 inhibits homologous recombination (3, 34, 58), we hypothesized that p53 might regulate the activation of ALT via its role in regulating inappropriate recombination. Here we demonstrate that transactivation-incompetent p53 causes growth inhibition in ALT but not in telomerase-positive cells. Growth inhibition is associated with a specific early S phase delay in ALT cells. In addition, we demonstrate that p53 may associate with telomeric DNA in vivo. As expected for a DNA binding protein, p53 is also associated with other sequences in the genome, such as α-satellite DNA and the p21WAF1 promoter. However, our data indicate that p53 may also associate with the telomere, making it possible that the growth inhibition seen in ALT cells, at least in part, is a result of p53 acting directly at the telomere. Finally, we show that p53 alleles defective in specific DNA binding and recombination suppression no longer inhibit DNA replication in ALT cells. These data are consistent with a model whereby p53 differentially inhibits growth of ALT cells by perturbing recombination between telomeres in a mechanism that requires a direct interaction of p53 with the telomeric complex. Alternatively, the processes underlying ALT might be detrimental to cellular survival, for example, by being associated with high levels of genome instability. In this scenario, the growth inhibition of ALT cells would not require either a direct inhibition of telomere maintenance by p53 or direct activation by dysfunctional telomeres of a p53-dependent pathway. Instead, elimination of this pathway would be necessary to allow cells to circumvent constitutive DNA damage checkpoint signaling. Because the p53 alleles used here have no transactivation activity, growth arrest induced by such a constitutive DNA damage signal would be elicited via some other activity of p53, such as transcriptional repression (46).

It has been demonstrated that p53 associates with the T loop in vitro (51), and thus p53 may be an integral component of the telomere, normally acting to prevent extension of telomere sequences from this partial Holliday junction. Regardless of whether p53 associates specifically with telomeres in ALT cells or is a constitutive component of all telomeres, in the model proposed above it would only act to limit growth in cells that are dependent upon recombination to maintain telomeres. Less telomeric DNA is reproducibly precipitated by anti-TRF2 from cells cultured at 32 than at 39°C. Although TRF2 is present on telomeres throughout the cell cycle (6), it is possible that there is a transient dissociation of TRF2 from the telomere when telomeres are elongated by ALT, which might become detectable due to the p53-induced enrichment of cells in S phase. In light of the potentially dynamic association of TRF2 with telomeres, it is intriguing to note the recent reports that dysfunctional telomeres actively engage other components of the DNA damage checkpoint machinery (14, 54). The direct demonstration of p53 association with telomeres in primary cells or telomerase-positive cells in vivo and the conditions under which such an association might occur have yet to be established and are topics worthy of further study.

All the ALT cell lines used here contain SV40 large T-Ag, which itself has been shown to have recombination promoting activity (52). Because ALT is a recombination-based mechanism, the presence of large T-Ag might affect this pathway. However, because both the telomerase-positive HIO114 and Meso6 cell lines analyzed here also contain SV40 (1, 19), any differences observed between the telomerase-positive and ALT cell lines cannot be attributable simply to the presence of large T-Ag. In addition, the results obtained here might have been confounded by the presence of endogenous p53, which in the case of the HIO107 and HIO114 cell lines has been determined to remain wild type (A.K. Godwin, unpublished results), in that overexpression of the exogenous p53 alleles might result in the release of endogenous p53 from large T-Ag. However, it is apparent that very little, if any, endogenous p53 is active in the cell lines expressing the p53TA allele because the p53-responsive p21WAF1 protein does not accumulate even after 48 h. Furthermore, the exogenous p53WT allele does not induce a phenotype at 39°C, indicating that the inactive protein does not compete with the endogenous p53 for binding to large T-Ag. This is consistent with observations that many mutant p53 proteins do not bind to large T-Ag (66). Thus, the phenotypes observed are most likely the result of the expression of the exogenous p53 alleles rather than a nonspecific effect of large T-Ag or the result of the endogenous p53 protein. Because these experiments were carried out using overexpressed protein, it is possible that endogenous p53 levels may not accumulate to sufficient levels to generate the growth inhibition phenotype. However, this is unlikely, given that the stabilization and accumulation of protein levels in response to DNA damage are a central regulatory mechanism for p53 (9).

Willers and coworkers (59) investigated various alleles of p53 with respect to their ability to suppress homologous recombination in mice. The homologous murine ts-p53 allele, V135A, exhibited a severely impaired DNA damage response at 37°C, indicating that a large proportion of the protein is in mutant conformation at this temperature. While the ts-p53 allele was still able to suppress recombination at 37°C, the activity was impaired relative to wild-type protein. Because these experiments were carried out at 37°C, the protein may retain some wild-type activity. In contrast to the study cited above, our analysis was carried out with human cells. In addition, the cultures used here were maintained at 39°C to ensure that the protein was in mutant conformation and unable to bind to DNA. Finally, p53 recognizes and binds to three-stranded DNA substrates in vitro, and its ability to suppress recombination in vivo requires both an intact core domain and an oligomerization domain (15). Thus, specific DNA binding by p53 is essential for the suppression of recombination. This is consistent with our ability to isolate clonal cell lines expressing ts-p53 alleles at 39°C when DNA binding and the suppression of recombination function are impaired (59). Taken together, the data indicate that ts-p53 is impaired in its ability to suppress recombination.

The suppression of recombination by p53 may occur through the recognition of altered DNA structures, such as single-stranded regions or cruciforms, and the targeting of cells containing these structures for apoptosis. However, the suppression of recombination by p53 does not require the transactivation function (15, 59), suggesting that p53 exerts its effect on recombination independent of gene expression. p53 is stabilized in S phase in response to replication blocks (21) or hypoxia (24). Although the stabilized protein is incompetent to induce many target genes (21), these observations suggest that p53 may have transactivation-independent functions in S phase, which in turn may be responsible for the delay of the normal S phase progression observed here. We propose one model in which the growth inhibition observed in the HIO107-TA cell lines is due to the perturbation of ALT-dependent telomere maintenance by p53. Although ALT cells contain many extremely long telomeres, growth inhibition occurs rapidly, within 48 h of ts-p53TA expression. We were unable to detect a global, catastrophic loss of telomeric sequences to account for this rapid induction of growth inhibition. This may be because ALT cells also contain a few chromosomes with extremely short telomeres (10, 40) that may activate telomere length-based checkpoints (14, 54) if not elongated. An analysis of telomeric end protection function, assayed by quantitating the frequency of anaphase bridges in mitosis, is precluded due to the growth inhibition occurring in S phase. In addition, because the growth defect seen here is different from the p53-dependent apoptotic response observed when telomere dysfunction is forced through the expression of dominant-negative TRF2 (28), the S phase delay is likely activated through a different pathway. Reintroduction of telomerase into ALT cell lines causes the preferential elongation of the short telomeres present in ALT cells (10, 23, 40) but, except in rare cases (20), does not result in the suppression of ALT (10, 23, 40). These cell lines provide a means of differentiating which of these two signals, critically short telomeres versus illegitimate recombination intermediates, is actually responsible for the observed growth inhibition. The identification of the initiating signal and downstream pathway generating the S phase delay seen here is worthy of future study.

We and others have previously demonstrated that APB-positive cells accumulate in the late S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle (22, 62) and suggested that these structures are coordinately regulated with the cell cycle. However, in the experiments conducted here, the presence of p53 causes both an accumulation of APB-positive cells and an accumulation of cells in early S phase. These results suggest that the monitoring of telomeres and/or the recombination reaction underlying telomere extension in ALT cells occurs in early S phase. The difference in the timing of the accumulation of APB-positive cells may be due to the absence of p53 in the cell lines previously studied, resulting in a delayed cellular response. In this scenario, APBs would be sites of telomeric recombination, which are stalled early in S phase by p53. BrdU incorporation at APBs has been reported previously and suggested to be a consequence of telomere replication by the ALT pathway (61). If so, then the BrdU incorporation at foci observed in the HIO107-TA cells at 32°C may consist of cells that have overcome the p53-dependent stall in S phase. Alternatively, APBs may form as a downstream response to a checkpoint signal, the timing of which is p53 dependent.

While loss of p53 has been correlated with a predilection for the activation of ALT rather than telomerase for telomere maintenance, the experiments described here are the first to directly test the role of p53 in ALT. Our data support a model whereby p53 plays a role in the regulation of ALT by perturbing telomeric recombination. Although this model provides one regulatory mechanism for the activation of ALT, it may not be the only one. ALT tumors derived from telomerase-deficient mice retain active p53, as judged by a robust DNA damage response (11). However, because the DNA damage response and suppression of recombination functions of p53 are separable (15, 59), it is not clear if these tumors are compromised for recombination suppression. Furthermore, tumors arising in mice deficient in both poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and p53 undergo telomere maintenance by ALT (56). This only occurs in the absence of p53, suggesting that p53 may also suppress activation of ALT in mice under the appropriate conditions. The data presented here suggest that p53-compromised cells may be more likely to activate ALT in response to telomerase inhibition than cells containing wild-type p53, clearly an important issue with respect to the therapeutic value of telomerase inhibitors in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by N.I.H. grants CA098087-01 (to D.B.), CA-45745-14 (to J.R.T.), and CA006927 (to Fox Chase Cancer Center) and D.O.D grant DAMD17-01-1-0724 (to D.B.).

We thank P. Adams and X. Ye for advice with cell cycle analysis and P. Adams, J. Chernoff, D. Kipling, and K. Zaret for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auersperg, N., S. Maines-Bandiera, J. Booth, H. Lynch, A. Godwin, and T. Hamilton. 1995. Expression of two mucin antigens in cultured human ovarian surface epithelium: Influence of a family history of ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 173:558-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayne, R. A., D. Broccoli, M. H. Taggart, E. J. Thomson, C. J. Farr, and H. J. Cooke. 1994. Sandwiching of a gene within 12 kb of a functional telomere and alpha satellite does not result in silencing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 3:539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertrand, P., D. Rouillard, A. Boulet, C. Levalois, T. Soussi, and B. S. Lopez. 1997. Increase of spontaneous intrachromosomal homologous recombination in mammalian cells expressing a mutant p53 protein. Oncogene 14:1117-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehden, G. S., N. Akyuz, K. Roemer, and L. Wiesmuller. 2003. p53 mutated in the transactivation domain retains regulatory functions in homology-directed double-strand break repair. Oncogene 22:4111-4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broccoli, D., L. A. Godley, L. A. Donehower, H. E. Varmus, and T. de Lange. 1996. Telomerase activation in mouse mammary tumors: lack of detectable telomere shortening and evidence for regulation of telomerase RNA with cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3765-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broccoli, D., A. Smogorzewska, L. Chong, and T. de Lange. 1997. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat. Genet. 17:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan, T. M., A. Englezou, L. Dalla-Pozza, M. A. Dunham, and R. R. Reddel. 1997. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat. Med. 3:1271-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan, T. M., A. Englezou, J. Gupta, S. Bacchetti, and R. R. Reddel. 1995. Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J. 14:4240-4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cadwell, C., and G. P. Zambetti. 2001. The effects of wild-type p53 tumor suppressor activity and mutant p53 gain-of-function on cell growth. Gene 277:15-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerone, M. A., J. A. Londono-Vallejo, and S. Bacchetti. 2001. Telomere maintenance by telomerase and by recombination can coexist in human cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:1945-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, S., C. M. Khoo, M. L. Naylor, R. S. Maser, and R. A. DePinho. 2003. Telomere-based crisis: functional differences between telomerase activation and ALT in tumor progression. Genes Dev. 17:88-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Q., A. Ijpma, and C. W. Greider. 2001. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1819-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho, Y., S. Gorina, P. D. Jeffrey, and N. P. Pavletich. 1994. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.d'Adda di Fagagna, F., P. M. Reaper, L. Clay-Farrace, H. Fiegler, P. Carr, T. Von Zglinicki, G. Saretzki, N. P. Carter, and S. P. Jackson. 2003. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 426:194-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudenhoffer, C., M. Kurth, F. Janus, W. Deppert, and L. Wiesmuller. 1999. Dissociation of the recombination control and the sequence specific transactivation function of p53. Oncogene 18:5773-5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudenhoffer, C., G. Rohaly, K. Will, W. Deppert, and L. Wiesmuller. 1998. Specific mismatch recognition in heteroduplex intermediates by p53 suggests a role in fidelity control of homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5332-5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunham, M. A., A. A. Neymann, C. L. Fasching, and R. R. Reddel. 2000. Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nat. Genet. 26:447-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.el-Deiry, W. S., T. Tokino, V. E. Velculescu, D. B. Levy, R. Parsons, J. M. Trent, D. Lin, W. E. Mercer, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1993. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75:817-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foddis, R., A. De Rienzo, D. Broccoli, M. Bocchetta, E. Stekala, P. Rizzo, A. Tosolini, J. V. Grobelny, S. C. Jhanwar, H. I. Pass, J. R. Testa, and M. Carbone. 2002. SV40 infection induces telomerase activity in human mesothelial cells. Oncogene 21:1434-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford, L. P., Y. Zou, K. Pongracz, S. M. Gryaznov, J. W. Shay, and W. E. Wright. 2001. Telomerase can inhibit the recombination-based pathway of telomere maintenance in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32198-32203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottifredi, V., S. Shieh, Y. Taya, and C. Prives. 2001. p53 accumulates but is functionally impaired when DNA synthesis is blocked. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1036-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grobelny, J. V., A. K. Godwin, and D. Broccoli. 2000. ALT-associated PML bodies are present in viable cells and are enriched in cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 113:4577-4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grobelny, J. V., M. Kulp-McEliece, and D. Broccoli. 2001. Effects of reconstitution of telomerase activity on telomere maintenance by the alternative lengthening to telomeres (ALT) pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:1953-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond, E. M., N. C. Denko, M. J. Dorie, R. T. Abraham, and A. J. Giaccia. 2002. Hypoxia links ATR and p53 through replication arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1834-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemann, M. T., M. A. Strong, L.-Y. Hao, and C. W. Greider. 2001. The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell 107:67-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henson, J. D., A. A. Neumann, T. R. Yeager, and R. R. Reddel. 2002. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in mammalian cells. Oncogene 21:598-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez, G. S., M. Nister, J. M. Stommel, M. Beeche, E. A. Barcarse, X. Q. Zhang, S. O'Gorman, and G. M. Wahl. 2000. A transactivation-deficient mouse model provides insights into Trp53 regulation and function. Nat. Genet. 26:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlseder, J., D. Broccoli, Y. Dai, S. Hardy, and T. de Lange. 1999. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science 283:1321-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S., L. Cavallo, and J. Griffith. 1997. Human p53 binds Holliday junctions strongly and facilitates their cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 272:7532-7539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, S., B. Elenbaas, A. Levine, and J. Griffith. 1995. p53 and its 14 kDa C-terminal domain recognize primary DNA damage in the form of insertion/deletion mismatches. Cell 81:1013-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, J., J. Chen, B. Elenbaas, and A. Levine. 1994. Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein. Genes Dev. 8:1235-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1-senescence. Cell 73:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez, J., I. Georgoff, J. Martinez, and A. J. Levine. 1991. Cellular localization and cell cycle regulation by a temperature-sensitive p53 protein. Genes Dev. 5:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekeel, K. L., W. Tang, L. A. Kachnic, C. M. Luo, J. S. DeFrank, and S. N. Powell. 1997. Inactivation of p53 results in high rates of homologous recombination. Oncogene 14:1847-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michalovitz, D., D. Halevy, and M. Oren. 1990. Conditional inhibition of transformation and of cell proliferation by a temperature-sensitive mutant of p53. Cell 62:671-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, D. A., V. Sharma, and A. R. Mitchell. 1988. A human-derived probe, p82H, hybridizes to the centromeres of gorilla, chimpanzee, and orangutan. Chromosoma 96:270-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson, D. M., X. Ye, C. Hall, H. Santos, T. Ma, G. D. Kao, T. J. Yen, J. W. Harper, and P. D. Adams. 2002. Coupling of DNA synthesis and histone synthesis in S phase independent of cyclin/cdk2 activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7459-7472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niida, H., Y. Shinkai, M. P. Hande, T. Matsumoto, S. Takehara, M. Tachibana, M. Oshimura, P. M. Lansdorp, and Y. Furuichi. 2000. Telomere maintenance in telomerase-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells: characterization of an amplified telomeric DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4114-4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opitz, O. G., Y. Suliman, W. M. Hahn, H. Harada, H. E. Blum, and A. K. Rustig. 2001. Cyclin D1 overexpression and p53 inactivation immortalize primary oral keratinocytes by a telomerase-independent mechanism. J. Clin. Investig. 108:725-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perrem, K., L. M. Colgin, A. A. Neumann, T. R. Yeager, and R. R. Reddel. 2001. Coexistence of alternative lengthening of telomeres and telomerase in hTERT-transfected GM847 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3862-3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quignon, F., F. DeBels, M. Koken, J. Feunteum, J. C. Ameisen, and H. de The. 1998. PML induces a novel caspase-independent death process. Nat. Genet. 20:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddel, R. R., T. M. Bryan, and J. P. Murnane. 1997. Immortalized cells with no detectable telomerase activity. A review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 62:1254-1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roemer, K., and N. Mueller-Lantzsch. 1996. p53 transactivation domain mutant Q22, S23 is impaired for repression of promoters and mediation of apoptosis. Oncogene 12:2069-2079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabbatini, P., J. Lin, A. J. Levine, and E. White. 1995. Essential role for p53-mediated transcription in E1A-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 9:2184-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saintigny, Y., D. Rouillard, B. Chaput, T. Soussi, and B. S. Lopez. 1999. Mutant p53 proteins stimulate spontaneous and radiation-induced intrachromosomal homologous recombination independently of the alteration of the transactivation activity and of the G1 checkpoint. Oncogene 18:3553-3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sang, B. C., J. Y. Chen, J. Minna, and M. S. Barbosa. 1994. Distinct regions of p53 have a differential role in transcriptional activation and repression functions. Oncogene 9:853-859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seeler, J. S., and A. Dejean. 1999. The PML nuclear bodies: actors or extras? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shay, J. W., and S. Bacchetti. 1997. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 33:787-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigal, A., and V. Rotter. 2000. Oncogenic mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor: the demons of the guardian of the genome. Cancer Res. 60:6788-6793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sood, A. K., J. Coffin, J. Sarvenaz, R. E. Buller, M. J. C. Hendrix, and A. Klingelhutz. 2002. p53 null mutations are associated with a telomerase negative phenotype in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 1:511-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stansel, R. M., D. Subramanian, and J. D. Griffith. 2002. p53 binds telomeric single strand overhangs and t-loop junctions in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11625-11628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.St.-Onge, L., L. Bouchard, and M. Bastin. 1993. High-frequency recombination mediated by polyomavirus large T antigen defective in replication. J. Virol. 67:1788-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sturzbecher, H. W., B. Donzelmann, W. Henning, U. Knippschild, and S. Buchhop. 1996. p53 is linked directly to homologous recombination processes via RAD51/RecA protein interaction. EMBO J. 15:1992-2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takai, H., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 2003. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr. Biol. 13:1549-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teng, S.-C., and V. A. Zakian. 1999. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8083-8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong, W. M., M. P. Hande, P. M. Lansdorp, and Z. Q. Wang. 2001. DNA strand break-sensing molecule poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cooperates with p53 in telomere function, chromosome stability, and tumor suppression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4046-4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiesmuller, L., J. Cammenga, and W. W. Deppert. 1996. In vivo assay of p53 function in homologous recombination between simian virus 40 chromosomes. J. Virol. 70:737-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willers, H., E. E. McCarthy, W. Alberti, J. Dahm-Daphi, and S. N. Powell. 2000. Loss of wild-type p53 function is responsible for upregulated homologous recombination in immortal rodent fibroblasts. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 76:1055-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willers, H., E. E. McCarthy, B. Wu, H. Wunsch, W. Tang, D. G. Taghian, F. Xia, and S. N. Powell. 2000. Dissociation of p53-mediated suppression of homologous recombination from G1/S cell cycle checkpoint control. Oncogene 19:632-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong, K. B., B. S. DeDecker, S. M. Freund, M. R. Proctor, M. Bycroft, and A. R. Fersht. 1999. Hot-spot mutants of p53 core domain evince characteristic local structural changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8438-8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu, G., X. Jiang, W. H. Lee, and P. L. Chen. 2003. Assembly of functional ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies requires Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1. Cancer Res. 63:2589-2595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu, G., W. H. Lee, and P. L. Chen. 2000. NBS1 and TRF1 colocalize at promyelocytic leukemia bodies during late S/G2 phases in immortalized telomerase-negative cells. Implication of NBS1 in alternative lengthening of telomeres. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30618-30622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu, L., J. H. Bayle, B. Elenbaas, N. P. Pavletich, and A. J. Levine. 1995. Alternatively spliced forms in the carboxy-terminal domain of the p53 protein regulate its ability to promote annealing of complementary single strands of nucleic acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:497-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, Q., R. Zhang, X. W. Wang, E. A. Spillare, S. P. Linke, D. Subramanian, J. D. Griffith, J. L. Li, I. D. Hickson, J. C. Shen, L. A. Loeb, S. J. Mazur, E. Appella, R. M. Brosh, Jr., P. Karmakar, V. A. Bohr, and C. C. Harris. 2002. The processing of Holliday junctions by BLM and WRN helicases is regulated by p53. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31980-31987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yeager, T., A. Neumann, A. Englezou, L. Huschtscha, J. Noble, and R. Reddel. 1999. Telomerase-negative immortalized human cells contain a novel type of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) body. Cancer Res. 59:4175-4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zambetti, G. P., and A. J. Levine. 1993. A comparison of the biological activities of wild-type and mutant p53. FASEB J. 7:855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]