Abstract

The pain of rejection is a crucial component of normal social functioning; however, heightened sensitivity to rejection can be impairing in numerous ways. Mindfulness-based interventions have been effective with several populations characterized by elevated sensitivity to rejection; however, the relationship between mindfulness and rejection sensitivity has been largely unstudied. The present study examines associations between rejection sensitivity and multiple dimensions of dispositional mindfulness, with the hypothesis that a nonjudgmental orientation to inner experiences would be both associated with decreased rejection sensitivity and attenuate the impact of sensitivity to rejection on general negative affect. A cross-sectional sample of undergraduates (n = 451) completed self-report measures of rejection sensitivity, dispositional mindfulness, and trait-level negative affect. Significant zero-order correlations and independent effects were observed between most facets of dispositional mindfulness and rejection sensitivity, with nonjudging demonstrating the largest effects. As predicted, rejection sensitivity was associated with negative affectivity for people low in nonjudging (β = .27, t = 5.12, p < .001) but not for people high in nonjudging (β = .06, t = .99, p = .324). These findings provide preliminary support for mindfulness, specifically the nonjudging dimension, as a protective factor against rejection sensitivity and its effects on affect.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Rejection Sensitivity, Nonjudgment, Awareness, Negative Affect

Feeling rejected is an adaptive part of the human experience, motivating the individual to perceive changes to their social support networks and to counteract such damage by either repairing damaged relationships or seeking out new ones (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004), ensuring that the one has adequate social support. However, some individuals demonstrate increased sensitivity to rejection, including heightened anticipation of potential social rejection and increased reactivity to perceived rejection (Downey, Feldman, Khuri, & Freedman, 1994; Feldman & Downey, 1994). High levels of rejection sensitivity are associated with many problems, including problems with relationships (Downey & Feldman, 1996), distress, and psychopathology. Rejection sensitivity is a defining characteristic of several psychological disorders, including borderline personality disorder (BPD; Staebler, Helbing, Rosenbach, & Renneberg, 2010), avoidant personality disorder (Posternak & Zimmerman, 2002), depression (Ayduk, Downey, & Kim, 2001), and social anxiety (Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer, & Klein, 1985). Rejection sensitivity may be linked to these problems through difficulties regulating emotion (Peters, Smart, & Baer, 2015), increased negative affectivity and distress (Gilbert, Irons, Olsen, Gilbert, & McEwan, 2006), more intense aggressive behavior (Ayduk, Gyurak, & Luerrsen, 2008), and heightened physiological responses to social experiences (Slavich, Way, Eisenberger, & Taylor, 2010).

Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective in treating disorders characterized by rejection sensitivity, including social anxiety (Goldin & Gross, 2010) and BPD (Linehan et al., 2006). Mindfulness is a multifaceted construct, typically defined as purposeful, nonjudgmental, and nonreactive awareness of and attention to the present moment (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Several of these dimensions of mindfulness could contribute to reduced sensitivity to rejection. The ability to approach experiences in a nonjudgmental, nonevaluative way may reduce the likelihood of becoming fused with catastrophic thoughts regarding the likelihood and consequences of rejection. The ability to exercise nonreactivity to one’s experience may reduce automatic, reflexive responses to rejection in favor of more reflective, adaptive responses. Increased attentional awareness could facilitate present-centered focus, decreasing worry and rumination. Finally, the ability to describe one’s experiences may reduce biases in social situations, promoting more balanced interpretations of the context. These mindfulness facets demonstrate both stable, between-person variance (i.e., dispositional mindfulness) and within-person fluctuations around one’s typical levels (Brown and Ryan, 2003; Eisenlohr-Moul, Peters, Chamberlain, & Rodriguez, under review). Furthermore, mindfulness training and associated use of mindfulness skills lead to relatively more permanent within-person changes in functioning (e.g., Carlson, Speca, Faris, & Patel, 2007).

In addition to affecting the degree of rejection sensitivity experienced by individuals, mindfulness could alter the impact of sensitivity to rejection on mood and other outcomes (Heppner et al., 2008). A nonjudgmental approach in particular might allow individuals to experience thoughts and feelings relating to rejection without engaging in self-critical, secondary elaborative processes about having those experiences (Roemer & Orsillo, 2010). While the perceived rejection causes pain, the added self-judgments that one is stupid, weak, or otherwise wrong or bad for having those feelings or having cared about the relationship in question likely amplifies distress considerably. In contrast, individuals sensitive to rejection who can accept the occurrence of painful rejection-related thoughts and feelings without judgment may be able to recover more quickly and experience less lasting impact on mood and functioning.

The present cross-sectional study utilized a non-meditating sample to investigate the relationships between these facets of dispositional mindfulness and rejection sensitivity. First, we hypothesized that nonjudging, nonreactivity, acting with awareness, and describing would all be negatively associated with rejection sensitivity. Nonjudging was predicted to have the strongest independent effect. Second, we hypothesized that the association between rejection sensitivity and trait negative affect would be attenuated among individuals who report a higher nonjudgmental orientation to experiences.

Methods

The present study utilized a cross-sectional, correlational, between-person design to examine associations between self-reported rejection sensitivity, mindfulness, and negative affect, as well as potential moderation of the association between rejection sensitivity and negative affect by the nonjudging facet of mindfulness.

2.1 Participants

Participants were 451 psychology students who completed an online survey of self-report measures as part of a larger study (see Peters, Smart, & Baer, 2015). Measures relevant to the present study are listed below (see Measures). In addition to these, participants completed the BPD features subscale of Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI-BOR; Morey, 2007), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), the Anger Rumination Scale (Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwell, 2001), and the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and all study procedures were approved by the institution’s IRB. Due to the relatively well-adjusted nature of most student samples, participant recruitment was designed to ensure that a wide range of rejection sensitivity, mindfulness, and negative affect would be represented. In order to accomplish this, participants were recruited in two ways. All students in the research pool were able to sign up for the study. In addition, recruitment emails were specifically sent to students who had, on a previous screening battery, scored in the clinically elevated range (T ≥ 70) on the PAI-BOR. Individuals in this range comprised 18.3% of the final sample. Previous research has demonstrated that BPD features are highly related to rejection sensitivity (Staebler et al., 2010), mindfulness (Wupperman, Neumann, & Axelrod, 2008), and negative affect (Salsman & Linehan, 2012).

2.2 Measures

Rejection sensitivity

The Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ; Downey & Feldman, 1996) is an 18-item measure of the tendency to experience anxiety or concern about the possibility of being rejected and the extent to which an individual expects to be rejected. Respondents are provided 18 brief scenarios and are asked to what degree they think it is likely that they will be rejected (1 = very unlikely to 6 = very likely) and how concerned they are about the potential rejection (1 = very unconcerned to 6 = very concerned), providing two scores for each scenario. Scores from each question are averaged across scenarios to create two subscale scores, which were then averaged together to create a single mean score. The RSQ has been shown to have good internal consistency (α = .81; Downey & Feldman, 1996).

Dispositional mindfulness

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006) is a 39-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess five facets of mindfulness. Sample items include: acting with awareness (“I rush through activities without being really attentive to them”—reverse scored); nonjudging of inner experiences (“I disapprove of myself when I have irrational ideas”—reverse scored); nonreactivity to inner experiences (“I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them”) describing (“I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings”); and observing (“I pay attention to sounds, such as clocks ticking, birds chirping, or cars passing”). The FFMQ was created through factor-analysis of five pre-existing measures of mindfulness. Participants are asked to rate the degree to which each statement applies to them on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1=Never or very rarely true, 5=Almost always or always true), providing a rating of the participant’s general tendency to be mindful. The FFMQ facets have demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency in previous research (α = .75–.91; Baer et al., 2006).

The FFMQ has been-validated in student samples; however, the observing subscale often does not show theoretically consistent associations in samples without meditation experience, sometimes even predicting increased rumination and poorer psychological health (e.g. Baer et al., 2008; Barnhofer, Duggan, & Griffith, 2011; Bowlin & Baer, 2012; Peters, Erisman, Upton, Baer, & Roemer, 2011; Peters, Smart, Eisenlohr-Moul, Geiger, Smith, & Baer, in press). One possible explanation for this inconsistency is that while experienced meditators may interpret observing items to mean noticing to their experiences in a nonjudgmental and nonreactive way, nonmeditators may not imbue observing items with such mindful qualities of attention (Baer, 2011; Baer et al., 2006). In contrast, the other four FFMQ facets perform consistently regardless of meditation experience level, demonstrating consistent associations in expected directions (Baer et al, 2006; 2008).

Negative affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1999) is a 60-item measure that asks respondents to rate their experiences of a variety of emotions on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 = very slightly, 5 = extremely). Multiple time frames can be used with this instrument; in the present study, participants were asked to rate their experiences of negative mood “in general,” thus providing a measure of trait-level affect. The PANAS-X was utilized in order to provide more comprehensive coverage of the construct of negative affect than the briefer, 10-item negative affect scale in the original PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The negative affect scale, comprised of the hostility (6 items), sadness (5 items), guilt (6 items), and fear (6 items) subscales, was used in the present study. This scale has demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency across several validation samples (α = 83–.90; Watson & Clark, 1999).

2.3 Data Analysis

Correlations were computed for all study variables. Each facet of the FFMQ, with the exception of observing due to previously mentioned validity concerns, was entered into a regression model predicting the RSQ to determine independent associations with rejection sensitivity. To test the effect of nonjudging on the relationship between rejection sensitivity and negative affectivity, both the FFMQ and RSQ variables were mean-centered, and the cross-product of the centered FFMQ nonjudging and RSQ was calculated. A regression model was fit predicting negative affect with the centered FFMQ facets and RSQ in step one and the cross-product in step two. A significant increase in variance accounted for in this step is interpreted as evidence for moderation (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003), in which case conditional values for the effect of rejection sensitivity on negative affect are obtained at +/− 1 SD of nonjudging.

Results

3.1 Data Screening

Several questions such as “Please choose ‘strongly disagree’ for this question” were included throughout the survey to ensure that participants were attending to both item content and the response scale. A final question was included at the end of the survey which asked participants if they answered the entire survey honestly (“I have tried to answer all of these questions honestly and accurately”). Participants who responded to the final question with “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” (n = 6) or who responded incorrectly to more than three quarters of the other questions embedded in the survey (n = 35) were excluded from analyses. These procedures resulted in the exclusion of 41 participants; therefore, data from 410 participants were used for analyses. This final sample of participants were 67.9% female and 80.8% white and ranged in age from 18 to 38 years with a mean age of 19.19 years (SD = 2.09).

All participants completed each self-report measure in full, so missing data was not estimated. Data were also screened for normality according to recommendations outlined by Tabachnick and Fidell (2000). All primary study variables were approximately normally distributed (skew/skew SE < 5; kurtosis/kurtosis SE < 5; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2000). Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1. Internal consistencies of all measures used were similar to previously obtained values (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Relationships Between the Self-Critical Rumination Scale and Related Constructs (N = 410).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rejection Sensitivity | (.86) | −.32*** | −.40*** | −.18*** | −.27*** | .07 | .38*** |

| 2. FFMQ Act Aware | (.89) | .59*** | −.01 | .33*** | −.28*** | −.35*** | |

| 3. FFMQ Nonjudging | (.91) | −.10 | .29*** | −.43*** | −.49*** | ||

| 4. FFMQ Nonreactivity | (.81) | .37*** | .41*** | −.12* | |||

| 5. FFMQ Describing | (.87) | .19*** | −.28*** | ||||

| 6. FFMQ Observing | (.85) | .19*** | |||||

| 7. Negative Affect | (.89) | ||||||

| Mean | 6.66 | 3.26 | 3.60 | 2.81 | 3.33 | 2.94 | 1.55 |

| SD | 2.43 | .79 | .89 | .72 | .77 | .80 | .65 |

p < .05.

p < .01

p < .001

Note. FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Act Aware = Acting with awareness. Crohnbach’s alpha values for each scale are presented in parantheses on the diagonal.

3.2 Zero-order Correlations

Zero-order correlations were computed to examine the relationships among mindfulness and rejection sensitivity (see Table 1). Analyses revealed significant negative correlations between rejection sensitivity and all facets of mindfulness except observing. This is consistent with previous findings that the observing facet of the FFMQ does not predict outcomes in expected directions in non-meditating samples (Baer et al., 2008); accordingly, this facet was excluded in subsequent analyses.

3.3 Mindfulness Facets as Independent Predictors of Rejection Sensitivity

The FFMQ facets acting with awareness, nonjudging, nonreactivity, and describing were all entered simultaneously into a regression model predicting the RSQ (see Table 2). The FFMQ facets in combination predicted about 25% of the variance in the RSQ. All of the facets except for describing were significant independent predictors of the RSQ. Nonjudging was the strongest predictor, with a moderate independent effect size, and acting with awareness and nonreactivity each had a small independent effect size.

Table 2.

Regression model of mindfulness facets predicting rejection sensitivity (N = 410).

| Dependent Variable | Predictors | β | R2 for model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection Sensitivity | Acting with Awareness | −.13* | |

| Nonjudging | −.31*** | ||

| Nonreactivity | −.17** | ||

| Describing | −.10 | ||

| .23** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

3.4 Does Nonjudging Attenuate the Association of Rejection Sensitivity with Negative Affectivity?

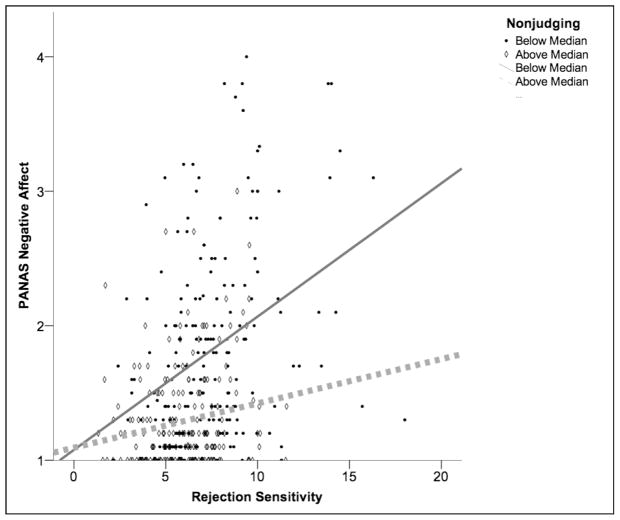

A final hypothesis was that greater nonjudging would weaken the link between rejection sensitivity and trait negative affectivity. Results of the multiple regression model can be found in Table 3. As predicted, there was a significant interaction between rejection sensitivity and nonjudging predicting trait negative affect over and above the conditional effects of the five facets of mindfulness and rejection sensitivity. Probing this interaction at one standard deviation above and below the mean of nonjudging revealed that there was a significant positive relationship between rejection sensitivity and negative affectivity among individuals low in nonjudging (standardized simple effect of rejection sensitivity at −1 SD nonjudging: βRSQ = .27, t = 5.12, p < .001), but that there was no significant association between rejection sensitivity and negative affectivity among individuals high in nonjudging (standardized simple effect of rejection sensitivity at +1 SD nonjudging: βRSQ = .06, t = .99, p = .324). Results of this model support the notion that higher levels of nonjudging are protective against the negative emotional consequences of sensitivity to social rejection.

Table 3.

Regression model of interaction between rejection sensitivity and nonjudging predicting negative affectivity (N = 410).

| Dependent Variable | Predictors | β | R2 for model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Negative Affect | Acting with Awareness | .08* | |

| Nonjudging | −.34*** | ||

| Nonreactivity | −.11** | ||

| Describing | −.12* | .34** | |

| Step 2: Negative Affect | Acting with Awareness | −.05 | |

| Nonjudging | −.32*** | ||

| Nonreactivity | −.09* | ||

| Describing | −.12* | ||

| Rejection Sensitivity | .16** | ||

| Rejection Sensitivity | |||

| X Nonjudging | −.13** | ||

| .36** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

To test the specificity of this buffering effect, we also constructed three alternate models with nonreactivity, acting with awareness, and describing as moderators of the effect of rejection sensitivity on negative affect. Models were constructed in the same manner as for nonjudging. Interactions with rejection sensitivity were not significant for any of the other mindfulness facets (nonreactivity: βRSQxNR = −.08, p = .092; acting with awareness: βRSQxAA = −.08, p = .098; describing: βRSQxDES = −.07, p = .122).

Discussion

The present study sought to examine the relations among the various aspects of dispositional mindfulness and rejection sensitivity. Consistent with hypotheses, all mindfulness facets except observing were associated with lower levels of rejection sensitivity. When examining independent associations between facets of mindfulness and rejection sensitivity, nonjudging demonstrated the largest independent relation, with acting with awareness and nonreactivity also demonstrating significant effects. These findings suggest that multiple facets of dispositional mindfulness, particularly nonjudgmental approach to inner experiences, are linked to a reduced tendency to experience anxiety about the possibility of rejection and to anticipate it.

Interaction models further indicated that nonjudging may be capable of attenuating the relationship between rejection sensitivity and negative affectivity. Bringing nonjudgmental awareness to one’s experiences may buffer individuals high in rejection sensitivity from experiences of negative affect. This interactive effect was specific to nonjudging, suggesting a unique role for this facet of mindfulness. Not only is a nonjudgmental approach to inner experiences less likely to be present for individuals high in rejection sensitivity, but it may also be more important to help regulate affect. Mindfulness-based interventions such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993; 2014) that emphasize nonjudging as a mindfulness skill may reduce the impact of rejection sensitivity on emotional functioning, and mindfulness skills more broadly might limit the extent of rejection sensitivity.

Further work should examine how these findings may extend to other problems associated with rejection sensitivity, such as aggressive behavior. Heightened rejection sensitivity predicts greater aggression following social rejection (Ayduk, et al., 2008), while mindfulness has been linked to decreased tendencies toward aggressive behavior (Borders, Earlywine, & Jajodia, 2010; Peters, et al., in press). If mindfulness is indeed capable of reducing rejection sensitivity and/or buffering the negative emotional reactions potentially produced through sensitivity to rejection, this may account for some of the effect of mindfulness on aggression.

The present study is cross-sectional, limiting the nature of the conclusions that can be drawn from these analyses. Further research examining relationships between mindfulness and rejection sensitivity should utilize longitudinal designs and mindfulness-based interventions to examine the effects of within-person variability and changes in mindfulness on rejection sensitivity. Additionally, utilizing assessment methods beyond self-report for these constructs, such examining how mindfulness affects responses of participants to in vivo experiences of rejection, such as with behavioral rejection paradigms, would increase external validity. Generalizability is also limited by the student sample; examining these constructs in community samples and relevant clinical samples would be useful. Despite these limitations, the current findings are preliminary evidence that mindfulness, particularly nonjudgment and acceptance, may have an important role in both the presence and the impact of rejection sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Graph of the interaction between rejection sensitivity and nonjudging predicting negative affectivity.

Note. Median split is utilized for presentation purposes only. Analyses were conducted using an interaction between two continuous variables (Nonjudging and Rejection Sensitivity).

Highlights.

Examined relationships between facets of mindfulness and rejection sensitivity (RS)

RS was negatively associated with multiple mindfulness facets, especially nonjudging

Increased nonjudging reduced the association between RS and trait negative affect

Mindfulness, specifically nonjudging, may be protective against RS and its effects

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this paper was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH093315).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ayduk Ö, Downey G, Kim M. Rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms in women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(7):868–877. [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk Ö, Gyurak A, Luerssen A. Individual differences in the regression-aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44(3):775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R, Smith G, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R, Smith G, Lykins E, Button D. Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. 2008;15(3):329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhofer T, Duggan DS, Griffith JW. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relation between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51(8):958–962. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Earleywine M, Jajodia A. Could mindfulness decrease anger, hostility, and aggression by decreasing rumination? Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(1):28–44. doi: 10.1002/ab.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre–post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2007;21(8):1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SH, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman S, Khuri J, Friedman S. Maltreatment and child depression. In: Reynolds WM, Johnson HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8(7):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Peters JR, Chamberlain K, Rodriguez M. Naturally occurring fluctuations in nonjudging predict borderline personality feature expression in women. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:231–247. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Irons C, Olsen K, Gilbert J, McEwan K. Interpersonal sensitivities: Their links to mood, anger and gender. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2006;79(1):37–51. doi: 10.1348/147608305X43856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10(1):83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner WL, Kernis MH, Lakey CE, Campbell WK, Goldman BM, Davis PJ, Cascio EV. Mindfulness as a means of reducing aggressive behavior: dispositional and situational evidence. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34(5):486–496. doi: 10.1002/ab.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Fyer AJ, Klein DF. Social phobia. Review of a neglected anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42(7):729–736. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300097013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. DBT® Skills Training Manual. 2. Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory Professional Manual. 2. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Erisman SM, Upton BT, Baer RA, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationships between dispositional mindfulness and impulsivity. Mindfulness. 2011;2(4):228–235. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0065-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Smart LM, Baer RA. Dysfunctional responses to emotion mediate the cross-sectional relationship between rejection sensitivity and borderline personality features. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2015;29(2):231–240. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Smart LM, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Geiger PJ, Smith GT, Baer RA. Anger rumination as a mediation of the relationship between mindfulness and aggression: The utility of a multidimensional mindfulness model. Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22189. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. The prevalence of atypical features across mood, anxiety, and personality disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):253–262. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.33498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Mindfulness- and Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapies in Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman NL, Linehan MM. An Investigation of the Relationships among Negative Affect, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation, and Features of Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34(2):260–267. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9275-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE. Neural sensitivity to social rejection is associated with inflammatory responses to social stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(33):14817–14822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009164107/-/DCSupplemental. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staebler K, Helbing E, Rosenbach C, Renneberg B. Rejection sensitivity and borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2010;18(4):275–283. doi: 10.1002/cpp.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN. Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4. Allyn & Bacon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: I. Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(1):33. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Useda D, Conforti K, Doan BT. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: 2. Two-year outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):307. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. University of Iowa; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wupperman P, Neumann CS, Axelrod SR. Do deficits in mindfulness underlie borderline personality features and core difficulties? Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(5):466–482. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]