Abstract

Objectives

To assess the role of nephrectomy as a risk factor for the development of hypertension and microalbuminuria.

Design

Prospective, long-term follow-up study.

Setting

Swiss Organ Living-Donor Health Registry.

Participants

All living kidney donors in Switzerland between 1993 and 2009.

Interventions

Data on health status and renal function before 1 year and biennially after donation were collected.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Comparison of 1-year and 5-year occurrences of hypertension among normotensive donors with 1-year and 5-year estimates from the Framingham hypertension risk score. Multivariate random intercept models were used to investigate changes of albumin excretion after donation, correcting for repeated measurements and cofactors such as age, male gender and body mass index.

Results

A total of 1214 donors contributed 3918 data entries with a completed biennial follow-up rate of 74% during a 10-year period. Mean (SD) follow-up of donors was 31.6 months (34.4). Median age at donation was 50.5 years (IQR 42.2–58.8); 806 donors (66.4%) were women. Donation increased the risk of hypertension after 1 year by 3.64 (95% CI 3.52 to 3.76; p<0.001). Those participants remaining normotensive 1 year after donation return to a risk similar to that of the healthy Framingham population. Microalbuminuria before donation was dependent on donor age but not on the presence of hypertension. After nephrectomy, hypertension became the main driver for changes in albumin excretion (OR 1.19; 95% CI 0.13 to 2.25; p=0.03) and donor age had no effect.

Conclusions

Nephrectomy propagates hypertension and increases susceptibility for the development of hypertension-induced microalbuminuria.

Keywords: Living kidney donation, Hypertension risk, nationwide cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The prospective design, the large donor group and the complete data sets are main assets of this study.

The study compared the effects with an adequate control group accounting for the lower cardiovascular risk of the donor group.

The study had an excellent overall follow-up rate of 74%.

Missing information on donors’ smoking habits and the family history of hypertension, required assumptions and sensitivity analyses.

The use of antihypertensive medication as a part of the hypertension definition may lead to an overstated number of hypertensives.

Introduction

Knowledge of the health consequences of living kidney donation, such as the risk of developing hypertension, may have important implication for the long-term medical follow-up of donors. So far it is uncertain whether nephrectomy alone is an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension and albuminuria. The occurrence of hypertension and albuminuria after kidney donation has been reported for decades, but as living organ donations continue to increase worldwide, the health risks of donation are viewed more positively.1 2 A meta-analysis of 48 studies reporting the outcome of 5145 donors showed a very minor and clinically non-relevant increased risk among kidney donors for the development of hypertension or proteinuria over long-term follow-up as compared to age-matched controls.3 4 However, the quality of the individual studies was limited by the retrospective study design, extensive loss to follow-up, small sample size resulting in underpowered statistical analyses and the common use of a normal population as control group, while donors are usually a positive selection and therefore healthier than the normal age-matched population.5

Only recently, a new multivariate score based on the Framingham data to calculate hypertension risks has become available that allows tackling the problem of inappropriate comparisons.6 The new score allows making groups comparable for gender, age, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, smoking habits and family history of hypertension. To date, no study, including among those summarised in the recent meta-analysis, applied the risk equation in the analysis. Therefore, the aim of this prospective, long-term follow-up study was to assess the role of nephrectomy as an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension and microalbuminuria in living kidney donors when compared to estimates from the multivariable hypertension risk score of the Framingham cohort including all relevant risk parameters of hypertension for potential donors without nephrectomy.

Methods

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocol used by the Swiss Organ Living-Donor Health Registry (SOL-DHR) to collect the data has been described in detail elsewhere.7 Briefly, all living kidney donors in Switzerland were enrolled before donation and followed 1 year after nephrectomy and biennially thereafter since 1993. Donors’ general practitioners provided medical follow-up data, which were collected by a central registry. So far, there are sequential data for up to 17 years after donation; the current analysis was restricted to a 10-year follow-up period due to the scarcity of data beyond this time period. This resulted in the exclusion of 185 database entries.

Hypertension was defined as blood pressure values above 140 mm Hg systolic and/or 90 mm Hg diastolic, or use of any blood pressure-lowering drug. Blood pressure data were reported as a mean of three individual measurements at each time point taken before and 1 year after donation and thereafter biennially during life-long follow-up examinations required by the Swiss transplant law. All new diagnoses of hypertension had to be verified by 24 h ambulatory blood pressure recording, using threshold values of 135/85 mm Hg or higher. Blood pressure values in the normal range were only accepted as ‘normal’ if a list of drugs taken the same day was reported to SOL-DHR to exclude antihypertensive treatment. Only follow-up examinations with complete data sets were analysed.

Urine albumin and urine creatinine were measured in a spot urine sample. A single central laboratory (Viollier AG, Basel, Switzerland) performed all chemical analysis in blood and urine. Microalbuminuria was defined as a ratio of mg albumin to mmol creatinine of 3.3 or more according to international guidelines.8

For statistical analysis, interval-scaled variates were summarised with means and SDs or medians and IQRs, where appropriate. Dichotomous variates were described as ratios and percentages. To assess the effect of donation on the occurrence of elevated blood pressure requiring medication, we fitted the hypertension risk score of the Framingham cohort6 for 1-year and 4-year risk of hypertension to our data as follows: for the first year analysis we fitted the data to the distribution prior to donation after excluding all cases of hypertension (n=271). For the subsequent 4-year analysis, we focused on all donors remaining normotensive 1-year after donation. Since data on smoking habits and family history of hypertension were not available in our data set, we created two random variates under the assumption of a smoking prevalence of 25% using the most recent epidemiological data of the tobacco monitoring study in Switzerland9 and took the strength of association from the hypertension risk score. We assumed positive family history (both parents) for hypertension of 25% using data of the Swiss survey on salt intake10 and again took the strength of association from the hypertension risk score. We found no Swiss data on the correlation between the two parameters and therefore assumed no correlation between smoking habits and positive family history of hypertension. We performed sensitivity analyses by repeating the analyses 100 times with each newly drawn random sample of the two parameters ‘smoking habits’ and ‘family history of hypertension’ and when assuming 20% and 30% prevalence rather than 25%.

The estimated probabilities from the Framingham equations were compared to the probabilities estimated from two multivariate logistic regression models, using the occurrence of hypertension 1 or 5 years after donation as the dependent variate and the available parameters of the Framingham equation (age, female gender, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), smoking habits, family history of hypertension and an interaction term of age and diastolic blood pressure) prior to donation (for the 1-year assessment) and at 12 months after donation (for the 4-year assessment).

To examine the parameters associated with microalbuminuria prior to donation, a multivariate logistic regression model was fitted using the following parameters as dependent variates (hypertension, donor age, male gender and BMI). To examine the occurrence of microalbuminuria in the follow-up, a multivariate random intercept model with hypertension as an independent variate and accounting for covariates (donor age, male gender and BMI) and corrected for repeated measures per donor, was fitted. This was carried out using the subject as a random factor. All analyses were performed using the Stata V.11.2 statistics software package (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

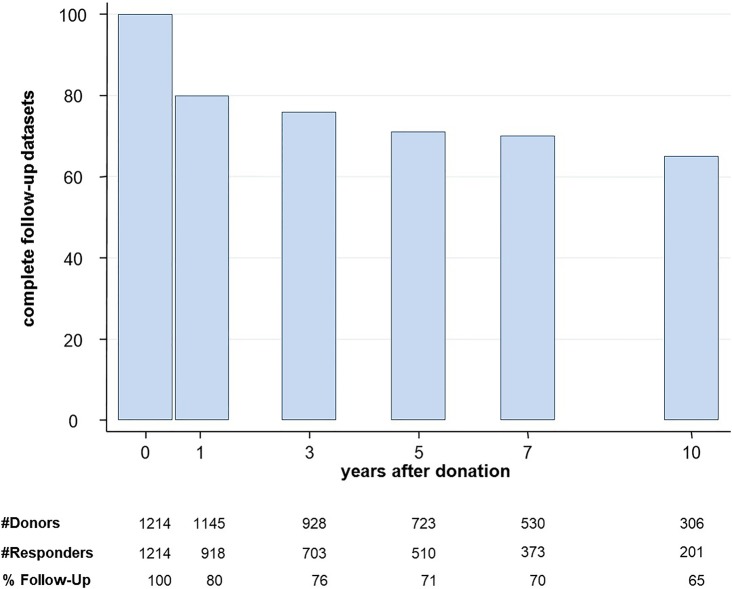

In the period from April 1993 to December 2009, all 1214 living kidney donors in Switzerland were enrolled in the SOL-DHR database, providing 3918 complete data sets with blood pressure measurements, microalbuminuria results and a list of drugs taken the day of blood pressure measurement. Figure 1 reports the number of donor follow-up examinations at each time point. Fifty-nine per cent of donors were related (28% parents, 26% siblings, 5% otherwise), 33% were living partners and 8% of donors were unrelated to the kidney recipient. During the 10-year follow-up period, 22 donors died from non-renal causes, resulting in 61 missed follow-up examinations. A total of 2704 complete data sets out of 3632 possible follow-up examinations were returned and analysed by SOL-DHR, resulting in an average follow-up rate of 74% over all time points. We checked whether those with hypertension at the 1-year follow-up were more likely to show up at the 5-year follow-up and found no significant difference (p=0.641).

Figure 1.

Rate of living kidney donors with complete datasets at each follow-up time point.

At the time of donation, median donor age was 50.4 years (IQR 42.1–58.7). Eight hundred and six donors (66.4%) were women and 408 (33.6%) were men. Median BMI of all donors was 24.9 (IQR 22.7–27.7). A total of 923 donors (76.0%) had normal blood pressure and 95.2% did not have microalbuminuria (ratio ≥3.3; median albumin-excretion ratio 0.7; IQR 0.4 –1.3).

At the time of donation, 271 donors (22.3%) were diagnosed with hypertension (information on hypertension was missing in 20 patients). In 89 patients (32.6%), the diagnosis of hypertension was made on the basis of blood pressure measurement. All other patients were classified on the basis of use of blood pressure-lowering medications. Mean systole was 140.7 (range 100–205) and mean diastole was 84.5 (range 60–113). table 1 reports a comparison with normotensive donors in terms of albumin excretion rate, gender, age and BMI.

Table 1.

Comparison of albumin excretion rate, age, gender and body mass index (BMI), between donors with and without hypertension before donation

| Donor characteristics before kidney donation |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive donors (n=271) | Normotensive donors (n=943) | ||

| Albumin excretion ratio | 1.29 (SD 1.55) | 1.22 (SD 3.02) | 0.72 |

| Age | 58.1 (SD 9.0) | 48.2 (SD 11.1) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 40.2% | 31.9% | 0.01 |

| BMI | 26.6 (SD 3.5) | 24.8 (SD 3.6) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index.

Occurrence of hypertension

Among initially normotensive donors, 398 (43.1%) developed hypertension in the observation period and provided 1302 data entries. Using the Framingham risk calculator, the predicted risk for developing hypertension 1 year after donation was increased by 3.64 (95% CI 3.52 to 3.76; p<0.001). The estimated mean 1-year risk of hypertension from the Framingham risk equation was 3.5%. The observed incidence of hypertension after 1 year among responders was 18.7% (151/807). In the subset of the donor cohort that remained normotensive 1 year after donation and had non-missing values for hypertension status 5 years after donation (n=451), the risk was only modestly increased (1.19, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.29; p <0.001). Two hundred and one patients provided data up to 10 years after donation. Occurrence of hypertension is shown in figure 2. One hundred and six remained normotensive. In the subgroup of donors remaining normotensive 5 years after donation, the cumulative incidence of developing hypertension in the subsequent 5 years was 29/123 (23.6%). Results remained essentially unchanged in sensitivity analyses. table 2 shows mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure values and ranges of hypertensive and normotensive groups during follow-up. All hypertensive patients remained hypertensive during the observation period. The mean systolic (6.2 mm Hg (95% CI 4.1 to 8.4 mm Hg); p<0.001) and diastolic (5.0 mm Hg (3.4 to 6.6 mm Hg); p<0.001) blood pressure values of normotensive donors predonation, who developed hypertension at 1-year follow-up, were slightly, albeit significantly, higher than the predonation values of those patients who were normotensive at the 1-year follow-up, when correcting for differences in age, male gender and BMI.

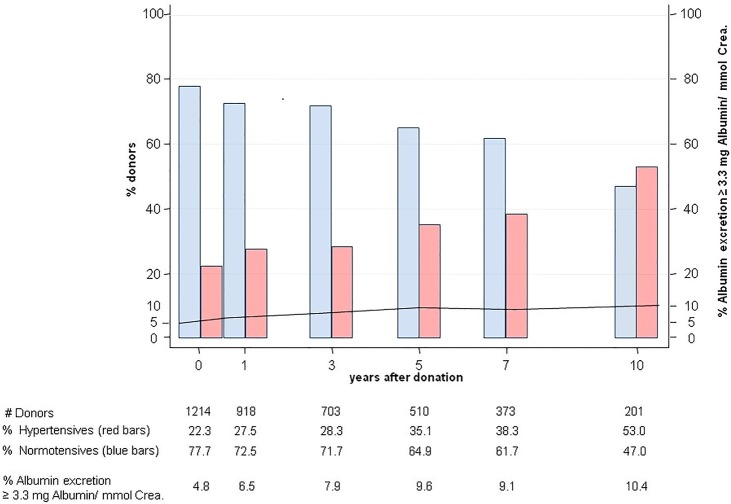

Figure 2.

Number of donors at risk of hypertension among 201 providing 10 years of follow-up.

Table 2.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure and ranges of hypertensive and normotensive groups, during follow-up

| Normotensive variable | Hypertensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Number | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Before donation | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 923 | 120.7 | 89 | 140 | 271 | 140.7 | 100 | 205 |

| Mean diastole | 923 | 74.9 | 46 | 90 | 271 | 84.5 | 60 | 113 |

| Number | 260 | |||||||

| 1 year | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 555 | 121.0 | 86 | 140 | 252 | 140.9 | 88 | 220 |

| Mean diastole | 555 | 77.1 | 50 | 90 | 252 | 87.3 | 60 | 116 |

| Number | 229 | |||||||

| 3 years | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 408 | 122.3 | 90 | 140 | 198 | 142.9 | 109 | 187 |

| Mean diastole | 408 | 78.4 | 59 | 90 | 198 | 86.4 | 60 | 110 |

| Number | 194 | |||||||

| 5 years | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 272 | 121.9 | 85 | 140 | 179 | 141.0 | 100 | 190 |

| Mean diastole | 272 | 78.0 | 56 | 90 | 179 | 85.3 | 60 | 115 |

| Number | 161 | |||||||

| 7 years | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 177 | 123.3 | 95 | 140 | 142 | 140.1 | 100 | 189 |

| Mean diastole | 177 | 78.2 | 53 | 90 | 142 | 84.3 | 61 | 109 |

| Number | 128 | |||||||

| 10 years | ||||||||

| Mean systole | 86 | 122.5 | 83 | 140 | 93 | 141.2 | 107 | 210 |

| Mean diastole | 86 | 77.1 | 59 | 90 | 93 | 84.0 | 60 | 111 |

| Number | 74 | |||||||

Number of hypertensive patients on ACE inhibitor or AT1 receptor antagonist treatment (italics).

Occurrence of microalbuminuria

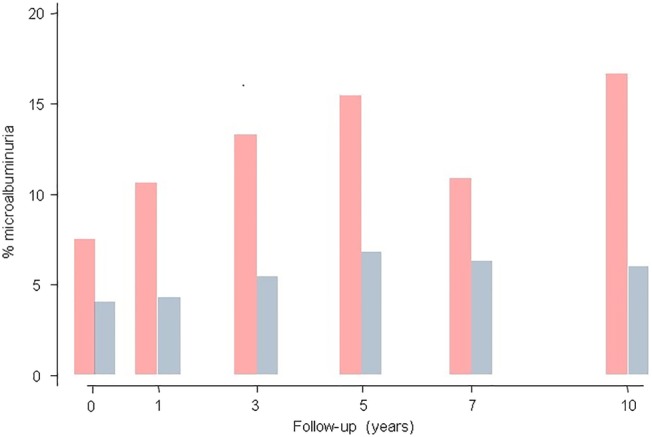

In all donors, the albumin excretion ratio increased from 1.2±2.7 to 1.9±10.7 mg albumin/mmol creatinine and the occurrence of microalbuminuria increased from 4.8% to 10.4% (figure 3). Twenty of 57 donors with microalbuminuria were hypertensive (35.1%). Ten years after nephrectomy, the rate of microalbuminuria (>3.3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine) was significantly higher in the group of 271 initially hypertensive donors as compared to normotensive donors (16.6% vs 6.0%, p=0.03) (figure 4). Before donation, albumin excretion was dependent on donor age but not on the presence of hypertension (table 1). However, after nephrectomy, multivariate random intercept models corrected for repeated measures per donor showed that the effect of age was lost and hypertension became the main driver for increased albumin excretion (OR 1.19; 95% CI 0.13 to 2.25; p=0.03).

Figure 3.

Rates of hypertension in living kidney donors over a 10-year follow-up period and microalbuminuria (>3.3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine) in the entire donor group, stratified for hypertensives (red bars) and normotensives (blue bars).

Figure 4.

Percentage of living kidney donors with microalbuminuria (>3.3 mg albumin/mmol creatinine) over a 10-year follow-up period and stratified for hypertensives (red bars) and normotensives (blue bars).

Discussion

Our results show that kidney donation triplicates the short-term risk among donors of developing hypertension and that after nephrectomy hypertension becomes the main risk factor for microalbuminuria.

In earlier studies, hypertension after living kidney donation was reported in 17–33% of donors.11–16 However, in the past, living kidney donation was not regarded as a risk factor for hypertension as the incidence of hypertension was similar to the age-matched general population.17–25 These studies were limited by their retrospective design, small donor cohorts, high rate of donors lost to follow-up and use of the general population as a control group.5 26 Also, a prospective study by Ramesh Prasad et al27 on 51 consenting donors who derived from a pool of 129 eligible donors, showed that the predonation 24 h ambulatory blood pressure dipping profile (nocturnal blood pressure dipping) of normotensive living kidney donors was not correlated with renal function and cardiovascular risk status at the 1-year follow-up after donation. Only recently, publications taking an opposite view have become available. In 2014, Mjoen et al28 published a paper estimating the all-cause and the cardiovascular mortality and risk for end-stage renal disease in kidney donors. Compared to a selected population of non-donors who would have qualified for to donate, the kidney donors showed an increased long-term risks for kidney failure and mortality. Very recently, results from the chronic renal impairment in Birmingham donor study showed that the unilateral nephrectomy in healthy subjects led to an increase in left ventricular mass that correlated with the reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) within 1 year.29

The classification of living kidney donors as being normotensive or hypertensive is not as easy as primarily expected. Normal blood pressure values do not allow a donor to be classified as being normotensive when no information is available on the use of antihypertensive drugs on the day of blood pressure measurement. On the contrary, hypertensive blood pressure readings without confirmation by 24 h blood pressure recording may reflect white coat hypertension.30 31 In our study, all new diagnoses of hypertension had to be verified by 24 h ambulatory blood pressure recording. Blood pressure values in the normal range were only accepted as ‘normal’ if a list of drugs taken the same day was reported to SOL-DHR. Only follow-up examinations with complete data sets were analysed. In 2006, Boudville et al3 concluded in their meta-analysis that there was on average a 5 mm Hg increase in blood pressure postnephrectomy but that they were unable to evaluate for any differences in risk of hypertension because of heterogeneity in the data and weaknesses in the underlying studies.

Strengths of the present study are the prospective design, the large donor group, a high follow-up rate and complete data sets, allowing a robust classification of hypertensive outcomes. In contrast to the follow-up of organ recipients, follow-up of donors is cumbersome as donors frequently live far from the transplant centres and regard themselves as healthy without the need for regular medical check-ups. Therefore, donors are usually not prepared to travel long distances or cover the expenses for their follow-up examinations. The key factor for the high follow-up rate in this prospectively designed long-term follow-up study was the Swiss transplant law requiring a central donor registry and coverage of medical expenses for donors’ biennial follow-up examination by the kidney recipients’ compulsory health insurance. At regular intervals, SOL-DHR provided donors with a questionnaire and medical follow-up form to be filled out by the donor's preferred local family physician, with all medical expenses covered by the recipients’ health insurance. Donors not returning their follow-up forms were contacted by SOL-DHR, using kidney recipients’ information, to obtain donor contact details; if abroad, donors were contacted through the worldwide network of Swiss embassies. Hence, we regard the rate of 74% complete follow-up examinations as the very best that can be achieved under ideal circumstances. The 2704 completed follow-up data sets allow for robust statistical analyses.

Missing information on donors’ smoking habits and the family history of hypertension is a weakness of this study. We tried to deal with it by imputing the missing data. In the case of smoking, we based our assumptions on the most recent epidemiological data on smoking available in Switzerland.9 In view of the fact that donors represent a healthy subgroup of the general public, we believe that this is a conservative assumption and think that the comparison is justifiable. Using lower rates for smoking would have increased the excess of risk among kidney donors. For positive family history, we assumed that 25% had both parents with hypertension. This assumption was based on a recently performed nationwide survey in Switzerland on salt intake.10 Again, it can be argued that this is a conservative assumption given the over-representation of healthy subjects in our cohort resulting in a potential underestimation of the risk of developing hypertension after donation. However, we cannot deny that the lack of data on two risk parameters that are used in the Framingham equation remains a problem. All we could do was to assess to what extend our assumptions affected the overall results. We were reassured that the results only varied minimally when repeating the analyses. Moreover, we cannot fully rule out that our definition of hypertension, taking use of antihypertensive medication as a part of the definition, led to an overstated number of hypertensive cases, because some normotensive patients might have received ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor antagonists against microalbuminuria or β-blockers against anxiety. Finally, even if a follow-up rate of 76% is very high, we cannot fully exclude selection bias.

Hypertension is a common disease in the general population, while kidney donors are a preselected healthier subgroup. Hence, even a tripling of the risk of hypertension, as shown in the present study, remained unnoticed when the subgroup of healthy donors was compared to the general population.17 23 32–35 Ideally, donors after nephrectomy should be compared to a population of accepted donors not able to donate owing to recipient reasons or those refusing nephrectomy but still being followed long term, to accurately reflect the specific risk profile of donors, including a high proportion of women (66%) or normal BMI. Under the assumption that the model is correct, the Framingham risk equation allowed making the control population similar for all relevant risk factors of hypertension. On the contrary, the Framingham risk score was not specifically validated for Switzerland and also does not take into account that many donors are first-degree relatives to someone with a kidney ailment or possibly cardiovascular disease.36 However, owing to the large group of donors with complete follow-up data sets collected prospectively by SOL-DHR during 17 years, it was possible to compensate for differences in the risk profile allowing a robust analyses of nephrectomy as an independent risk factor for hypertension.

Unilateral nephrectomy deprives the group of healthy donors of their initial health advantage and puts them at a threefold higher risk for developing hypertension. Those participants remaining with normal blood pressure 1 year after donation return to a risk similar to that of the healthy Framingham population.

The second goal of this study was to assess the role of nephrectomy as an independent risk factor for microalbuminuria. Previous studies on small donor groups reported an increase in microalbuminuria, which was believed to be due to hyperfiltration of the remaining glomeruli after nephrectomy.17 23 32–35 Indeed, in the present donor cohort, GFR as estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula37 shows, despite removing half of the kidney mass, not the theoretically expected fall to 50% of its initial value but, instead, a reduction to approximately 70%, indicating hyperfiltration of the remaining glomeruli. Over the 10-year follow-up period with 2704 serum creatinine measurements after nephrectomy, GFR remained stable with no sign of normal physiological loss of GFR due to ageing or hyperfiltration.38 In addition we could now identify hypertension as an important driver for the development of microalbuminuria after nephrectomy.

Another relevant finding was obtained by analysing the risk factors for microalbuminuria in donors before and after nephrectomy. Before nephrectomy, variability in albumin excretion was related to donor age but not the presence of hypertension. However, after unilateral nephrectomy, hypertension became the dominant factor for albumin excretion, whereas donor age had no effect. The possible underlying mechanisms explaining this phenomenon remain unclear and warrant additional (patho-)physiological investigations.

In summary, kidney donation increases the risk among donors for developing hypertension and sensitises the remaining kidney to hypertensive glomerular damage as expressed by increased albumin excretion. Whether such increased risk of developing hypertension and/or microalbuminuria translates into renal dysfunction, other morbidities or mortality, postdonation, remains to be seen. However, both risks must be addressed by offering donors life-long follow-up and providing continued monitoring of blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion. As hypertension becomes the main risk factor for microalbuminuria, adequate therapy with nephroprotective antihypertensive drugs (ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists) should be initiated as soon as kidney donors are diagnosed with hypertension. Transplant centres have to be aware of their responsibility to organise long-term follow-up schemes for living kidney donors to guarantee their optimal medical long-term management. Follow-up should be coordinated by the transplant centre or a central registry, but performed by the family physician in the donor's neighbourhood, to ensure life-long medical support.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the medical/surgical team and the transplant coordinators of the Transplant Centres of Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, St Gallen and Zürich. The authors would like to thank Ruth Lützelschwab and Christina Wolf-Heidegger for secretarial help. The authors are grateful to Thomas Voegele (transplant coordinator) for his initial participation when SOL-DHR was initiated (1993) and Hanspeter Hort (graphic artist) for designing the SOL-DHR logo free of charge. The authors thank Guy Kollwelter and Heinz Herrmann (both from Astellas) for providing us with medals and individual diplomas for living donors.

Footnotes

Contributors: GTT conceived the study and was in the main responsible for the study design and study management. CN, DT and JS were involved in data collection and management. LMB and GTT designed the analysis plan and LMB performed the statistical analyses. GTT, JS and LMB drafted the manuscript. All the authors provided important intellectual input and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Viollier AG, Novartis Pharma Schweiz AG, Alfred and Erika Baer-Spycher-Stiftung, Astellas Pharma AG, Fresenius Medical Care (Switzerland) AG, Roche Pharma (Switzerland) AG. AMGEN (Switzerland) AG, Fresenius Biotech GmbH, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals AG, Spirig Pharma AG, diverse private sponsors. Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Nephrologie SGN, Bundesamt für Gesundheit, HP Hort, Pfizer AG, Sanofi-Aventis (Switzerland) AG, Genzyme GmbH, HU Böhi, P Roth Yin Yee, Oliver Boidol, B Braun Medical AG, Schweizer Nierenliga, Gambro Hospital (Switzerland) AG, Baxter AG.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of Basel, Switzerland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Morgan BR, Ibrahim HN. Long-term outcomes of kidney donors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2011;20:605–9. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834bd72b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Housawi AA, Young A, Boudville N et al. . Transplant professionals vary in the long-term medical risks they communicate to potential living kidney donors: an international survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:3040–5. 10.1093/ndt/gfm305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudville N, Prasad GV, Knoll G et al. . Meta-analysis: risk for hypertension in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:185–96. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-3-200608010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg AX, Muirhead N, Knoll G et al. . Proteinuria and reduced kidney function in living kidney donors: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Kidney Int 2006;70:1801–10. 10.1038/sj.ki.5001819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ommen ES, Winston JA, Murphy B. Medical risks in living kidney donors: absence of proof is not proof of absence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;1:885–95. 10.2215/CJN.00840306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ et al. . A risk score for predicting near-term incidence of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:102–10. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiel GT, Nolte C, Tsinalis D. Prospective Swiss cohort study of living-kidney donors: study protocol. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000202 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS, Cattran D, Friedman A et al. . Proteinuria as a surrogate outcome in CKD: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by The National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:205–26. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller R, Radtke T, Krebs H et al. . Tobacco consumption of the Swiss population between 2001–2010 2011. http://www.tabakmonitoring.ch/Berichte/Factsheets/factsheet_tobacco_10_en.pdf (accessed 17 Feb 2016).

- 10.Chappuis A, Bochud M, Glatz N et al. . Swiss survey on salt intake: main results 2011. http://www.blv.admin.ch/dokumentation/00327/05754/index.html?download=NHzLpZeg7t,lnp6I0NTU042l2Z6ln1ah2oZn4Z2qZpnO2Yuq2Z6gpJCFfX59g2ym162epYbg2c_JjKbNoKSn6A--&lang=it (accessed 17 Feb 2016).

- 11.Torres VE, Offord KP, Anderson CF et al. . Blood pressure determinants in living-related renal allograft donors and their recipients. Kidney Int 1987;31:1383–90. 10.1038/ki.1987.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toronyi E, Alfoldy F, Jaray J et al. . Evaluation of the state of health of living related kidney transplantation donors. Transpl Int 1998;11(Suppl 1):S57–9. 10.1007/s001470050426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato K, Satomi S, Ohkohchi N et al. . Long-term renal function after nephrectomy in living related kidney donors. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1994;95:394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Donnell D, Seggie J, Levinson I et al. . Renal function after nephrectomy for donor organs. S Afr Med J 1986;69:177–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu KH, Poon CK, Lam CM et al. . Long-term outcomes of living kidney donors—a single centre experience of 29 years. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012;17:85–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg AX, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook HR et al. , Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension risk in living kidney donors: an analysis of health administrative data in Ontario, Canada. Transplantation 2008;86:399–406. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817ba9e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiel GT, Nolte C, Tsinalis D [The Swiss Organ Living Donor Health Registry (SOL-DHR)]. Ther Umsch 2005;62:449–57. 10.1024/0040-5930.62.7.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Duner F, Brink B et al. . No evidence of accelerated loss of kidney function in living kidney donors: results from a cross-sectional follow-up. Transplantation 2001;72:444–9. 10.1097/00007890-200108150-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldfarb DA, Matin SF, Braun WE et al. . Renal outcome 25 years after donor nephrectomy. J Urol 2001;166:2043–7. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65502-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramcharan T, Matas AJ. Long-term (20-37 years) follow-up of living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 2002;2:959–64. 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.21013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlaovic PD, Richardson RM, Miller JA et al. . Living donor nephrectomy: follow-up renal function, blood pressure, and urine protein excretion. Can J Urol 1999;6:901–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Agroudy AE, Sabry AA, Wafa EW et al. . Long-term follow-up of living kidney donors: a longitudinal study. BJU Int 2007;100:1351–5. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gossmann J, Wilhelm A, Kachel HG et al. . Long-term consequences of live kidney donation follow-up in 93% of living kidney donors in a single transplant center. Am J Transplant 2005;5:2417–24. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizvi SA, Naqvi SA, Jawad F et al. . Living kidney donor follow-up in a dedicated clinic. Transplantation 2005;79:1247–51. 10.1097/01.TP.0000161666.05236.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Kvarnström N, Söfteland JM et al. . Post-nephrectomy development of renal function in living kidney donors: a cross-sectional retrospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2377–81. 10.1093/ndt/gfr161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L et al. . Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:459–69. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramesh Prasad GV, Lipszyc D, Sarker S et al. . Twenty four-hour ambulatory blood pressure profiles 12 months post living kidney donation. Transpl Int 2010;23:771–6. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.01040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A et al. . Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 2014;86:162–7. 10.1038/ki.2013.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moody WE, Ferro CJ, Edwards NC et al. , CRIB-Donor Study Investigators. Cardiovascular effects of unilateral nephrectomy in living kidney donors. Hypertension 2016;67:368–77. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ommen ES, Schröppel B, Kim JY et al. . Routine use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in potential living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:1030–6. 10.2215/CJN.01240307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLoach SS, Meyers KE, Townsend RR. Living donor kidney donation: another form of white coat effect. Am J Nephrol 2012;35:75–9. 10.1159/000335070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nogueira JM, Weir MR, Jacobs S et al. . A study of renal outcomes in African American living kidney donors. Transplantation 2009;88:1371–6. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c1e156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azar SA, Nakhjavani MR, Tarzamni MK et al. . Is living kidney donation really safe? Transplant Proc 2007;39:822–3. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdu A, Morolo N, Meyers A et al. . Living kidney donor transplants over a 16-year period in South Africa: a single center experience. Ann Afr Med 2011;10:127–31. 10.4103/1596-3519.82077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasiske BL, Ma JZ, Louis TA et al. . Long-term effects of reduced renal mass in humans. Kidney Int 1995;48:814–19. 10.1038/ki.1995.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skrunes R, Svarstad E, Reisætter AV et al. . Familial clustering of ESRD in the Norwegian population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:1692–700. 10.2215/CJN.01680214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibrahim HN, Rogers T, Tello A et al. . The performance of three serum creatinine-based formulas in estimating GFR in former kidney donors. Am J Transplant 2006;6:1479–85. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bock HA, Gregor M, Huser B et al. . [Glomerular hyperfiltration following unilateral nephrectomy in healthy subjects]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1991;121:1833–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]