Abstract

Objective

To clarify the problems related to maternal deaths in Japan, including the diseases themselves, causes, treatments and the hospital or regional systems.

Design

Descriptive study.

Setting

Maternal death registration system established by the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG).

Participants

Women who died during pregnancy or within a year after delivery, from 2010 to 2014, throughout Japan (N=213).

Main outcome measures

The preventability and problems in each maternal death.

Results

Maternal deaths were frequently caused by obstetric haemorrhage (23%), brain disease (16%), amniotic fluid embolism (12%), cardiovascular disease (8%) and pulmonary disease (8%). The Committee considered that it was impossible to prevent death in 51% of the cases, whereas they considered prevention in 26%, 15% and 7% of the cases to be slightly, moderately and highly possible, respectively. It was difficult to prevent maternal deaths due to amniotic fluid embolism and brain disease. In contrast, half of the deaths due to obstetric haemorrhage were considered preventable, because the peak duration between the initial symptoms and initial cardiopulmonary arrest was 1–3 h.

Conclusions

A range of measures, including individual education and the construction of good relationships among regional hospitals, should be established in the near future, to improve primary care for patients with maternal haemorrhage and to save the lives of mothers in Japan.

Keywords: maternal mortality, postpartum hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, DIC, maternal death

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the large, recent nationwide study in Japan, to analyse the problems related to maternal deaths, including the diseases themselves, causes, treatments and hospital or regional systems.

The fact that the deaths of approximately half of the pregnant women who died due to obstetric haemorrhage were potentially preventable will be useful information for obstetric caregivers.

A limitation of the present study is bias due to the descriptive study design, which was subjectively evaluated by the Committee members.

Since the participants included only cases who died, further evaluations in near missed cases are needed to fully comprehend the pregnancy-related maternal emergency in Japan.

Introduction

The current maternal mortality rate in Japan, which is estimated to be around 4 in 100 000 deliveries,1 is similar to that in other developed countries. In 2010, the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG) established a registration system and the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee (Chairman T Ikeda) to further reduce the number of maternal deaths. In order to provide information that could help in the prevention of maternal deaths, and to improve the quality of obstetric healthcare, the Committee conducted a causal analysis of each maternal death and reported its recommendations for general obstetrical practice by which the number of maternal deaths due to similar causes could be reduced.

This Committee, which issues its recommendations on an annual basis, has published several studies.2–4 In these previous reports, we emphasised that the immediate detection and interpretation of abnormal conditions, and the efficient provision of primary care, were required to prevent maternal deaths. The present study focused on the preventability of maternal deaths in Japan, in a manner that is similar to an analysis reported two decades ago.5

The objective of the present study was to clarify the problems in maternal deaths, including the diseases themselves, causes, treatments and hospital and regional systems, in order to analyse the preventability of each death, and to make recommendations to reduce the number of maternal deaths in Japan.

Methods

Women who died during pregnancy or within a year after delivery (late maternal death defined as the death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetrical causes more than 42 days but less than 1 year after termination of pregnancy, was included), from January 2010 to June 2014, throughout Japan, and whose detailed reports were submitted to the JAOG and analysed by the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee, were enrolled as participants in the present study.

Review and analysis of maternal deaths

In cases of maternal death, report forms regarding the death were submitted to the registration system of the JAOG. The 22 pages of the report form contain approximately 100 questions that aim to elicit detailed information about the clinical history, the facility characteristics and the personnel who participated in the patient's care. Medical records, including the anaesthetic record, medical images, laboratory data and pathological and autopsy reports, were also collected.

All of the anonymised reports were analysed for factors associated with maternal mortality and the circumstances of death by the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee, which consists of 15 obstetricians, 4 anaesthesiologists, 2 pathologists, an emergency physician and some specialists. A causal analysis report on each case of maternal death, including the most probable cause and recommendations, was made by the Committee and provided to the institution at which the death occurred.

Analysis of maternal death preventability

The Committee also evaluated the deficiencies in ambulatory and hospital care, and whether the care met basic community practice standards. After a deep discussion about the quality of the care and the cause of death, the preventability of the death was assessed in each case. Accidental deaths and deaths that were not evaluable due to a lack of information or unexplained causation were excluded from the analysis of preventability.

The concerns about the clinical management associated with the maternal deaths, including the diagnosis and treatment of diseases themselves, the timing of blood transfusion or maternal transport, and the intrahospital or interhospital (at regional hospitals) preparation of treatment and systems, were also analysed in each case. The Committee members primarily assigned each case of maternal death to one of two categories of preventability: possible and impossible (0%). Then, in the cases where the prevention of maternal death was considered to be possible, preventability was classified subjectively into one of three subcategories: slightly (10–30%), moderately (40–70%) or highly (80%) possible. Finally, preventability in each case was decided by a majority vote among the Committee members.

Definitions

Accidental death: In the present study, accidental death included deaths by suicide and traffic accident.

Obstetric haemorrhage: Obstetric haemorrhage was defined as massive bleeding in association with pregnancy, including placental abruption, atonic bleeding, uterine rupture, uterine inversion, placenta accreta, cervical and vaginal laceration, and uterine amniotic fluid embolism (based on a clinical and/or pathological diagnosis). A uterine amniotic fluid embolism was considered to have occurred when fetal debris and amniotic fluid components were found in the uterus in the pathological examination of cases of severe uterine haemorrhage after placental removal (such as atonic bleeding) in the absence of other obstetric haemorrhagic complications such as abnormal placentation, trauma during labour and delivery, and severe preeclampsia/eclampsia. This condition usually results in the rapid development of consumptive coagulopathy/disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Brain disease: Brain disease included cerebral stroke and cerebral venous embolism as diagnosed by brain imaging.

Amniotic fluid embolism: Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) was defined based on the Japan consensus criteria for the diagnosis of AFE (which is based on the US/UK criteria) as follows: (1) if symptoms appeared during pregnancy or within 12 h of delivery; (2) if any intensive medical intervention was conducted to treat one or more of the following symptoms/diseases: (a) cardiac arrest, (b) severe bleeding of unknown origin within 2 h of delivery (≥1500 mL), (c) disseminated intravascular coagulation, (d) respiratory failure and (3) if the findings or symptoms obtained could not be explained by other diseases. As for AFE, consumptive coagulopathy/DIC due to evident aetiologies such as abnormal placentation, trauma during labour and delivery, and severe preeclampsia/eclampsia, should be excluded.6

Statistical analyses

p Values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software program (Windows V.20.0 J; Chicago, Illinois, USA). Continuous variables were subjected to the Mann-Whitney U test and are reported as the median and range. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test and are reported as frequencies.

Results

A total of 213 maternal death reports were completely analysed by the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee, from 2010 to 2014. Among these, 59% (125) and 23% (49) were categorised as direct and indirect pregnancy-associated deaths, respectively. Ten cases were accidental deaths and 29 cases were not evaluable.

The causes and evaluations of the maternal deaths that occurred in Japan, from 2010 to 2014, and which were evaluated by the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee, are shown in table 1. The frequent causes of maternal deaths were obstetric haemorrhage (23%), brain disease (16%), amniotic fluid embolism (12%), heart and cardiovascular disease (8%), pulmonary disease (8%) and infectious disease (7%).

Table 1.

The causes of maternal deaths and preventability as evaluated by the Maternal Death Exploratory Committee in Japan, from 2010 to 2012 (n=213)

| Cause of death | Frequency (n) |

|---|---|

| Obstetric haemorrhage | 23% (49) |

| Uterine-artery focused amniotic fluid embolism | 23 |

| Atonic bleeding | 6 |

| Uterine rupture | 6 |

| Placental abruption | 4 |

| Uterine inversion | 4 |

| Placenta accreta | 3 |

| Cervical and vaginal laceration | 3 |

| Brain disease | 16% (35) |

| Cerebral stroke | 34 |

| Cerebral venous embolism | 1 |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 12% (27) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8% (17) |

| Aortoclasia | 6 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 3 |

| Cardiac infarction | 2 |

| Long QT syndrome | 2 |

| Myocarditis | 1 |

| Mitral valve stenosis | 1 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 |

| Right subclavian venous rupture | 1 |

| Pulmonary disease | 8% (16) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 13 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 3 |

| Infectious disease | 7% (15) |

| Group A streptococcal infection | 8 |

| Septic shock | 4 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 |

| Bacterial meningitis | 1 |

| Liver disease | 2% (4) |

| Liver rupture | 2 |

| Acute hepatitis | 2 |

| Convulsion | 1% (2) |

| Others | 1% (3) |

| Malignant disease | 3% (6) |

| Stomach cancer | 3 |

| Ureter cancer | 1 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 1 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 |

| Trauma | 5% (10) |

| Suicide | 8 |

| Traffic accident | 2 |

| Unexplained | 14% (29) |

| Not evaluable | 10 |

| Lack of information | 19 |

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 168 participants who remained after the exclusion of deaths due to malignant disease, accidental deaths and unexplained cases (table 2). The median age (range) was 34 years (19–45 years), and 51% of the deaths occurred in nulliparous women. Six cases did not regularly attend pregnancy checkups. Forty-three per cent of the deaths occurred in transvaginal deliveries, whereas 42% occurred in caesarean section deliveries. Most of deaths were confirmed at a hospital and autopsies were performed in 42% of the deaths.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the participants (n=168)

| Maternal characteristics | |

| Maternal age (median, range) | 34 (19–45) |

| Gravida (median, range) | 1 (0–9) |

| Parity (median, range) | 0 (0–6) |

| Nulliparous | 51% (85) |

| Skipped pregnancy checkups | 4% (6) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Normal spontaneous delivery | 23% (38) |

| With uterine fundal pressure | 5% (8) |

| Instrumental delivery | 15% (26) |

| Caesarean section | 42% (70) |

| After artificial abortion in 1st trimester | 1% (2) |

| Before delivery | 14% (24) |

| Maternal death | |

| At hospital | 96% (167) |

| At clinic | 1% (1) |

| Autopsy | 42% (70) |

Table 3 shows the results of the analyses of the symptoms and maternal transport (table 3). In more than half of the cases, the onset of the initial symptoms occurred after delivering the baby or during caesarean section. In 35% of the deaths, the initial symptoms occurred in the third trimester or during labour. Two cases died after an artificial abortion in the first trimester (pulmonary embolism and stroke of arteriovenous malformation). The initial symptoms occurred in a medical facility in 71% of cases and outside of a medical facility in 29%. The initial cardiopulmonary arrest occurred at a clinic in 12% of deaths, at a hospital in 70%, in a midwifery home in 1% and outside of a medical facility in 10% of cases. Maternal transport was required in 58% of deaths (median (quartile range) distance of transport 5 km (3–11 km)). In 9 of the 13 cases who suffered cardiopulmonary arrest in an ambulance, cardiopulmonary arrest occurred when patients were being transported between medical facilities because of limitations of the primary care provider.

Table 3.

The analyses of the symptoms and maternal transport (n=168)

| Onset of initial symptoms | |

| First trimester | 3% (5) |

| After artificial abortion in 1st trimester | 1% (2) |

| Second trimester | 8% (14) |

| Third trimester | 21% (36) |

| During labour | |

| 1st stage | 7% (12) |

| 2nd stage | 7% (11) |

| 3rd stage | 5% (9) |

| During caesarean section | 8% (13) |

| Postpartum | 39% (66) |

| Location at the onset of initial symptoms | |

| At clinic | 27% (46) |

| At hospital | 43% (72) |

| At midwifery home | 1% (2) |

| Outside of medical facilities | 29% (48) |

| Initial cardiopulmonary arrest | |

| At clinic | 12% (20) |

| At hospital | 70% (117) |

| At midwifery home | 1% (1) |

| During transport on ambulance | 8% (13) |

| Outside of medical facilities | 10% (17) |

| Maternal transport between medical facilities | |

| No | 42% (70) |

| Clinic to hospital | 19% (32) |

| Single obstetrician on duty at clinic | (5) |

| Two obstetricians on duty at clinic | (8) |

| ≥3 obstetricians on duty at clinic | (19) |

| Hospital to higher degree hospital | 8% (13) |

| Hospital to perinatal centre | 30% (51) |

| Midwifery hospital to hospital | 1% (2) |

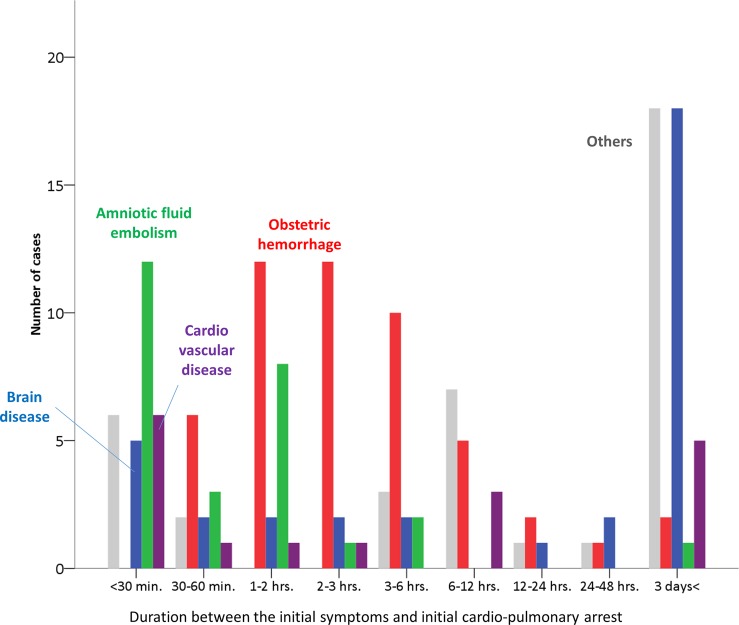

The duration between the initial symptoms and initial cardiopulmonary arrest in the patients who died due to causes associated with obstetric haemorrhage, brain disease, cardiovascular disease, AFE and the other causes, is demonstrated in figure 1. In maternal deaths due to causes associated with obstetric haemorrhage, the peak duration between the initial onset of symptoms and cardiopulmonary arrest was 1–3 h, while in no cases did cardiopulmonary arrest occur within 30 min from initial symptom. On the other hand, the initial cardiopulmonary arrest occurred within 30 min in most cases with AFE. Cardiovascular disease was also likely to involve immediate cardiopulmonary arrest.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the durations between the initial symptoms and the initial cardiopulmonary arrest stratified by the major causes of maternal death, including obstetric haemorrhage (red bars), amniotic fluid embolism (green bars), brain disease (purple bars) and cardiovascular disease (blue bars).

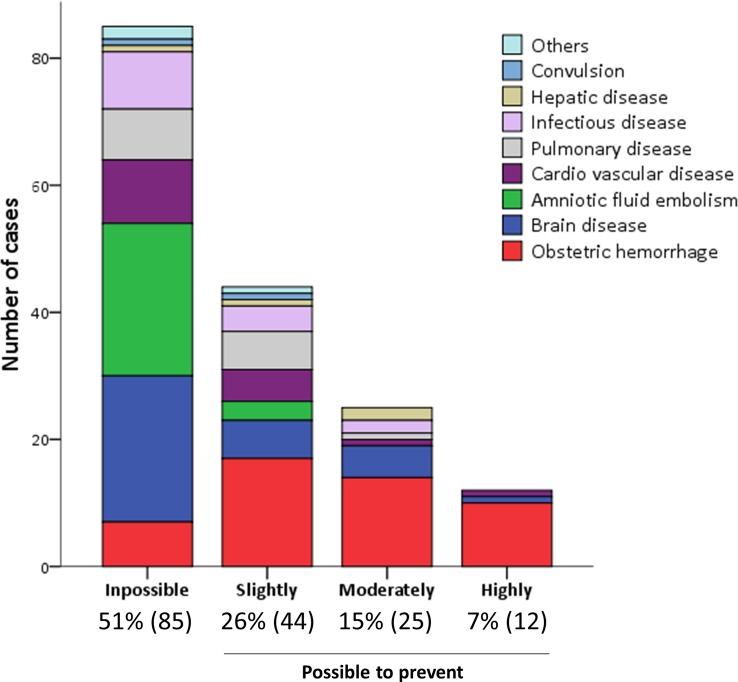

The causes of maternal death stratified by preventability are shown in figure 2. The Committee considered that it was impossible to prevent maternal death in 51% of cases, slightly possible in 26%, moderately possible in 15% and highly possible in 7% of cases. The Maternal Death Exploratory Committee considered it difficult to prevent deaths in most cases that involved AFE or brain disease. In contrast, the Committee considered it possible to prevent maternal deaths in cases of obstetric haemorrhage. Deaths due to obstetric haemorrhage accounted for most of the cases in which it was considered that there was a high possibility of preventing maternal death.

Figure 2.

The number of maternal deaths of each cause stratified by preventability.

Among the 85 cases in which it was thought to be impossible to prevent maternal death, 80 cases (94%) were due to the rapidly progressive condition of disease. The cases in which the Committee thought that it was possible to prevent maternal death and in which there were concerns about clinical management are shown in table 4, stratified by the possibility of prevention (table 4). Delays in the diagnosis and treatment, including not only maternal transport, medications, blood transfusion and surgical interventions, but also their systems, were associated with the possibility of prevention.

Table 4.

The analyses of the concerns about clinical management associated with maternal death stratified by the possibility of prevention in preventable cases (n=81)

| Possibility to prevent | Slightly | Moderately | Highly |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–30% n=44 |

40–70% n=25 |

80% n=12 |

|

| Delayed diagnosis | |||

| Owing to rare disease | 14% (6) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| However, not rare disease | 16% (7) | 60% (15) | 75% (9) |

| Delayed decision of maternal transport from primary hospital | |||

| 30% (13) | 52% (13) | 33% (4) | |

| Delayed blood transfusion | |||

| RCC | 23% (10) | 44% (11) | 75% (9) |

| FFP | 32% (14) | 52% (13) | 75% (9) |

| Platelet | 2% (1) | 8% (2) | 8% (1) |

| Delayed treatment | |||

| Medication | 23% (10) | 36% (9) | 67% (8) |

| Surgical intervention | 21% (9) | 28% (7) | 42% (5) |

| Delayed delivery | 6% (2) | 25% (4) | 11% (1) |

| Inappropriate resuscitation or anaesthesia | |||

| 7% (3) | 20% (5) | 33% (4) | |

| Insufficient preparation | |||

| 30% (13) | 52% (13) | 33% (4) | |

| Concerning system | |||

| Maternal transport | 2% (1) | 8% (2) | 8% (1) |

| Blood transfusion | 11% (5) | 4% (1) | 33% (4) |

| Communication | |||

| Intrahospital | 16% (7) | 20% (5) | 50% (6) |

| Interhospital | 2% (1) | 0% (0) | 17% (2) |

FFP, fresh frozen plasma; RCC, red cell concentrates.

Discussion

In Japan, approximately 2500 facilities provide delivery services for approximately one million deliveries per year. Since pregnant women often place importance on the accessibility and comfort of the delivery facilities, deliveries are not intensively performed and more than half of all deliveries are managed in private clinics operated by one or sometimes two obstetricians. Nevertheless, the perinatal mortality rate in Japan was 4:1000 in 2012,1 which is the lowest in the world. Furthermore, the maternal mortality rate, which was 8.8 in 1992 and 4.0 per 100 000 births in 2012, respectively,1 has decreased by half over the past two decades. Given that the maternal mortality rate in Japan is among the lowest in the world, it can be said that the safety standards of prenatal practice in Japan are at least equivalent to the standards of other developed countries.

The JAOG established a registration and causal analysis system to achieve a further decrease in the number of maternal deaths in 2010. Thereafter, they began to release annual recommendations to note important reminders and potential improvements to reduce the number of maternal deaths that occur in perinatal care. The present report is based on the results of this system and describes the current status of maternal death in Japan. We also assessed the preventability of each case of maternal death and extracted the issues involved in the goal of contributing to the improvement of safety in perinatal care.

Although the maternal mortality rate decreased between 1992 and 2014, the most frequent cause of maternal death was massive obstetric haemorrhage throughout the period. The incidence of obstetric haemorrhage reduced from 38% to 23%. Fifty-two per cent of all maternal deaths occurred after a transvaginal delivery or caesarean section. More than half of the maternal deaths that were caused by obstetric haemorrhage (29/49) were associated with atonic bleeding. Among these, 23 cases were pathologically diagnosed with an amniotic fluid embolism of the uterine artery after fetal debris and amniotic fluid components were found in the removed uterus (after the exclusion of other obstetric haemorrhagic complications). Since this condition often results in the rapid onset of consumptive coagulopathy, it is considered difficult to prevent.

On the other hand, some cases were associated with unimproved continuous small bleeding and were expected to be managed over an extended time period because they did not involve sudden massive bleeding. This meant, especially in cases of atonic bleeding, that incomplete uterine rupture, silent uterine bleeding into the abdominal cavity, and cervical and vaginal laceration treatment, were often delayed until the onset of sudden, obvious severe symptoms such as an impaired consciousness and cardiopulmonary arrest. The vital signs in pregnant women were likely to remain relatively good due to homeostasis, even during haemorrhage, and to then suddenly deteriorate after a massive haemorrhage. Since postpartum haemorrhage is not a diagnosis, and the treatment for each of these conditions is different, it was previously recommended that caregivers should aggressively pursue a specific diagnosis of postpartum haemorrhage and provide appropriate specific therapy for that diagnosis.7

The second most frequent cause of death was brain disease, which accounted for 14% of maternal deaths in 1992 and 16% in 2014. In 1992, the third most frequent cause of maternal death (9%) was hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, such as pulmonary oedema and hepatic necrosis due to Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, Lowered Platelets (HELLP) syndrome or acute fatty liver.6 In the present analysis, 30 of the maternal deaths involved complications of pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) (14% of all deaths). Although we did not include hypertensive disorders in the category of final causation of the death, the final diagnosis of the direct cause of maternal death was cerebral stoke in 50% of the PIH cases. Hepatic haemorrhage, AFE, pulmonary oedema and convulsion were also considered to be the other causes of death associated with PIH. Cerebral stroke remains a significant cause of maternal death in pregnant patients with hypertensive disorder.3 Although half of the deaths due to brain disease were considered to be impossible to prevent, the immediate appropriate management of hypertension during pregnancy and early maternal transport to a high-grade hospital are recommended. In the previous recommendation, ‘preventing maternal death—10 clinical diamonds’, it was described that any hospitalised patient with preeclampsia experiencing either a systolic blood pressure of 160 or a diastolic pressure of 110, should receive an intravenous antihypertensive agent within 15 min,7 because cerebral haemorrhage secondary to uncontrolled hypertension remains a leading cause of death in women with preeclampsia.7 8

The third most frequent cause of death in 2014 was AFE (12%). The Maternal Death Exploratory Committee considered such deaths were the most difficult to prevent due to the severity of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy itself. AFE affects an estimated 1 in every 50 000 women giving birth.9 It is estimated that the fatality rate ranges from 11% to 61%, and the rate in a more recent series was lower than it was 30 years previously.10

The rate of cardiovascular disease increased from 3% in 1992 to 10% in 2014. It was estimated that pulmonary embolism comprised 7% of maternal deaths in 2014, and 9% in 1992.6 We previously reported that the incidence of maternal deaths associated with venous thromboembolism in Japan has decreased over the past 20 years, however, the incidence during pregnancy has been increasing.1 The Maternal Death Exploratory Committee considered it difficult to prevent more than the deaths of pregnant women with cardiovascular disease and pulmonary embolism.

The Committee, still, considers it impossible to prevent over half of all maternal deaths, even if appropriate management or intensive care in the tertiary hospital were to be provided, due to the severity of the patients' conditions. On the other hand, in cases in which it was considered to be possible to prevent maternal death, delays in the diagnosis and treatment, including maternal transport, intervention and blood transfusion, and their systems, were associated with maternal death. In fact, such cases had several problems in the diagnostic procedures, treatment strategies and the interhospital and intrahospital systems. In 2000, it was reported that inadequate obstetric services were associated with maternal mortality in Japan and that reducing the number of deliveries in single-obstetrician facilities and establishing regional 24 h inpatient obstetric facilities for high-risk cases might reduce maternal mortality in Japan.5 However, 58% (98 cases) of maternal deaths still occur after maternal transport between medical facilities. In particular, 15 cases were transferred from a facility in which only one or two obstetricians were on duty or from a midwifery home.

Among women who died in the UK in 2009–2012, nearly three-quarters had a coexisting medical complication.11 There has been no significant change in the rate of indirect maternal death over the past 10 years, a time during which direct maternal deaths have decreased by half.11 Similar to the UK, direct maternal death remains responsible for more than half of the deaths in Japan (59%). Although it would be difficult to change the distribution of number of clinics and tertiary hospitals in the near future, in particular, improvements in the management of cases of obstetric haemorrhage are required in Japan. We believe that this can be effective in reducing the maternal mortality rate because the peak duration between the initial symptoms and initial cardiopulmonary arrest was 1–3 h. There were no cases of massive obstetric haemorrhage in which cardiopulmonary arrest occurred within 30 min. Caregivers in delivery services should reconsider the strategies that they apply in dealing with obstetric haemorrhage. It is important to consider both, changes in the vital signs at the early stage, and the treatment capacity of each facility (under cooperation with the centre hospital).

We therefore strongly recommend that prevention should start prior to the occurrence of an adverse event, from trimester-specific management of high-risk women to active management of labour. It is noteworthy that adverse events frequently occurred even in clinics with ≥3 obstetricians on duty—and in the postpartum stage. The following points should be incorporated into the management of postpartum haemorrhage. First, in cases of postpartum haemorrhage, vital signs and the amount of bleeding should be immediately perceived; efficient primary care, including haemostasis, vital care and primary resuscitation, are required in cases of obstetric haemorrhage. Second, in cases of haemorrhagic shock, blood transfusion (FFP and RCC) should be immediately prepared; if it is not possible to obtain a blood supply, then the patient should be immediately transported to the centre hospital. Third, strong lines of regional communication should be established at both, the interhospital and intrahospital levels; stronger ties are required among the caregivers in primary delivery services, such as clinics, which engage a single obstetrician and doctors in regional tertiary centre hospitals. The obstetricians at small-scale facilities should develop a good relationship with not only obstetricians, but also with the emergency doctors, anaesthesiologists, interventional radiologists, paediatricians and other members of the hospital staff at the tertiary hospital, and all medical providers should work in perfect unison in the event of an emergency.

Conclusion

Although maternal mortality has decreased by half in Japan during the past two decades, the Committee considered that the deaths of approximately half of the pregnant women who died due to obstetric haemorrhage were potentially preventable. In the near future, the initial care of patients with maternal massive haemorrhage should be improved, and good relationships should be established among regional hospitals to save the lives of mothers in Japan.

Footnotes

Contributors: JH, AS and TI conceived the study, JH and AS wrote the initial protocol, analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors collected the data and analysed each maternal death. JH, AS, HT and TI coordinated the study and, with JH and HT, produced the database and analysed the data. All the authors contributed to writing the paper. II, KK and TI are the guarantors for the study. All the authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by a Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (grant number 24090101) and JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 15K10688).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics board of National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Osaka, Japan, and the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. This investigation was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was not obtained from patients nor from their families, because this study was based on the analysis of institutional forms, and the patient records/information was anonymised prior to the analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kamiya K, ed. Maternal and child health statistics in Japan. Tokyo: Mothers; ' and Children's Health and Welfare Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka H, Katsuragi S, Osato K et al. Increase in maternal death-related venous thromboembolism during pregnancy in Japan (2010–2013). Circ J 2015;79:1357–62. 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa J, Sekizawa A, Yoshimatsu J et al. Cases of death due to serious group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in pregnant females in Japan. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;291:5–7. 10.1007/s00404-014-3440-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa J, Ikeda T, Sekizawa A et al. Maternal death due to stroke associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Circ J 2015;79:1835–40. 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagaya K, Fetters MD, Ishikawa M et al. Causes of maternal mortality in Japan. JAMA 2000;283:2661–7. 10.1001/jama.283.20.2661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanayama N, Tamura N. Amniotic fluid embolism: pathophysiology and new strategies for management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2014;40:1507–17. 10.1111/jog.12428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark SL, Hankins GD. Preventing maternal death: 10 clinical diamonds. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119Pt 1):360–4. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182411907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA et al. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:36.e1–5; discussion 91-2 e7-11 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight M, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P et al. Incidence and risk factors for amniotic-fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:910–17. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d9f629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonnell NJ, Percival V, Paech MJ. Amniotic fluid embolism: a leading cause of maternal death yet still a medical conundrum. Int J Obstet Anesth 2013;22:329–36. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman RL, Lucas DN. MBRRACE-UK: saving lives, improving mothers' care—implications for anaesthetists. Int J Obstet Anesth 2015;24:161–73. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]