Abstract

Objective

To examine associations between sexual behaviour, sexual function and sexual health service use of individuals with depression in the British general population, to inform primary care and specialist services.

Setting

British general population.

Participants

15 162 men and women aged 16–74 years were interviewed for the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3), undertaken in 2010–2012. Using age-adjusted ORs (aAOR), relative to a comparator group reporting no treatment or symptoms, we compared the sexual health of those reporting treatment for depression in the past year.

Outcome measures

Sexual risk behaviour, sexual function, sexual satisfaction and sexual health service use.

Results

1331 participants reported treatment for depression (5.2% men; 11.8% women). Relative to the comparator group, treatment for depression was associated with reporting 2 or more sexual partners without condoms (men aAOR 2.07 (95% CI 1.38 to 3.10); women 2.22 (1.68 to 2.92)), and concurrent partnerships (men 1.80 (1.18 to 2.76); women 2.06 (1.48 to 2.88)), in the past year. Those reporting depression treatment were more likely to be dissatisfied with their sex lives (men 2.32 (1.74 to 3.11); women 2.30 (1.89 to 2.79)), and to score in the lowest quintile on the Natsal-sexual function measure. They were also more likely to report a recent chlamydia test (men 1.92 (1.15 to 3.20)); women (1.27 (1.01 to 1.60)), and to have sought help regarding their sex life from a healthcare professional (men 2.92 (1.98 to 4.30); women (2.36 (1.83 to 3.04)), most commonly from a family doctor. Women only were more likely to report attending a sexual health clinic (1.91 (1.42 to 2.58)) and use of emergency contraception (1.98 (1.23 to 3.19)). Associations were broadly similar for individuals with depressive symptoms but not reporting treatment.

Conclusions

Depression, measured by reported treatment, was strongly associated with sexual risk behaviours, reduced sexual function and increased use of sexual health services, with many people reporting help doing so from a family doctor. The sexual health of depressed people needs consideration in primary care, and mental health assessment might benefit people attending sexual health services.

Keywords: Depression, Sexual health, Sexual health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The major strength of this study lies in the comprehensive data collected on sexual behaviour, function and health service use linked to self-reported information on depression in a large probability sample. The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) considered sexual health in its broadest sense according to the WHO-endorsed definition, and furthermore used the Natsal-SF measure, which takes account not only of sexual difficulties, but also the relationship context and overall levels of sexual satisfaction.

The response rate for Natsal-3 (57.7%) was similar to other major social surveys, however, there may be systematic biases in who agrees to take part. To minimise this, we weighted the data to match the age, sex and regional profile of the British population according to the 2011 census. Once these weights had been applied, the Natsal-3 sample composition was generally comparable with the British population in terms of marital status, ethnic group, and self-reported general health.19–21

Although the potential for reporting bias was minimised by using computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) and non-response weighting, our cross-sectional data should be interpreted with caution, and we note that causality cannot be assumed.

In prioritising sexual health data collection, we relied on self-reporting of treatment for depression to an interviewer using computer-assisted personal interview (rather than objective clinical diagnosis or longer diagnostic tools), to identify a clinically meaningful group that would be relevant to family doctors and sexual health specialists. Although the prevalence and distribution of depression according to age, health and other factors matched data from other studies and data sources, we are not able to distinguish between pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression, the stage of treatment, or the extent to which treatment might be attenuating symptoms. We included a second measure of depression using the PHQ-2 screening tool, and found similar patterns of associations with a range of dependent sexual health variables for the group screening positive for recent depressive symptoms. This observation serves both to validate our findings and is suggestive of a population group with depressive symptoms and poor sexual health who might not be accessing, or adequately served by, healthcare services.

The study is restricted to those reporting sexual experience who answered the Natsal-3 CASI, which corresponds to more than 95% of the British population.

Introduction

In the UK, the estimated point prevalence of a major depressive episode among those aged 16–74 years is 2.6%, with less severe depression present in 9.1% of men and 13.6% of women.1 Over 90% of adults with depression are managed in primary care by their family doctor,2 and depression forms a large part of general practice (GP) case load, presenting in up to a quarter of GP attendees.3 4 Psychological morbidity is also common in attendees of specialist sexual health clinics (ie, genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics); one study found that over half the patients attending a London GUM clinic had experienced symptoms of depression, anxiety, or both in the past month,5 but this phenomenon is not well studied.

Depression has profound effects on quality of life, including sexual interest and behaviour.6 Studies, primarily in the USA and in adolescents, have shown associations between depression and sexual risk behaviours,7–11 and two North American studies extended these findings to adults.12 13 Sexual dysfunction and depression frequently occur together, but the nature of their association is not well understood. Although reduced desire is most often reported, problems with arousal, resulting in vaginal dryness in women and erectile dysfunction in men, and absent or delayed orgasm are also common, and erectile dysfunction is sometimes used as a marker for depression.14 15 Understanding the interaction between depression and sexual function is complicated by difficulty in determining the direction of causality,16 17 the fact that patient groups are rarely treatment naïve, and by whether the condition or its treatment has the largest effect, since most antidepressants have undesired effects on sexual function.18

Few studies have investigated the overlap between sexual and mental well-being across the life course, and little is known about the sexual behaviour and sexual health service use of individuals with depression in the general population. This paper uses data from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) to investigate the nature and strength of associations between depression and sexual behaviour, sexual function and sexual health service use in a representative sample of the British population aged 16–74 years.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Full details of the methods of Natsal-3 have been reported elsewhere.19–21 Briefly, households across Britain were selected using stratified probability sampling from which one eligible individual was selected at random and invited to participate. Altogether, 15 162 men and women aged 16–74 years were interviewed between September 2010 and August 2012. The overall response rate was 57.7%, and the cooperation rate was 65.8% (defined as the number of interviews completed from eligible addresses for which contact was made).19 22 An anonymised data set has been deposited with the UK Data Service, persistent identified: 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7799–1, and the complete questionnaire and technical report are available on the Natsal website (http://www.natsal.ac.uk/home.aspx).

Participants were interviewed in their own homes by professional interviewers using computer-assisted personal interview. Participants were asked whether they had been diagnosed or treated for a range of chronic health conditions, listed on showcards,23 from which participants selected those they had experienced. In this way, a card was used to ask participants, ‘Are you currently taking any type of medicine prescribed by a doctor for depression?’. Participants subsequently completed a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI), which included a validated patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2), comprising two screening questions (‘During the past 2 weeks have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?’, and ‘During the past 2 weeks have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?’) to assess depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks (each scored 0–3).24 Participants were deemed to have depressive symptoms if they had a total score of three or more, a cut-off that has been previously validated.25

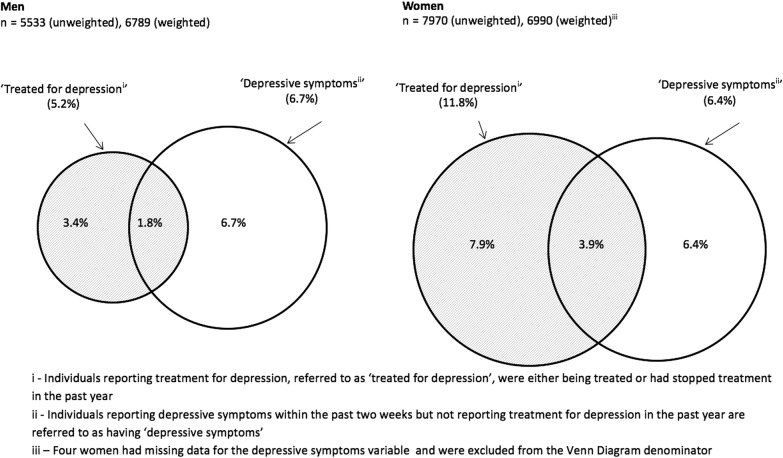

We identified a number of permutations in the groups that might be selected for analysis. To focus the analysis for a clinical practice audience, we selected three mutually exclusive groups of participants for comparison who might be readily defined in a clinical setting (figure 1), (1) individuals reporting treatment for depression, hereafter referred to as ‘treated for depression’, who were either being currently treated or had stopped treatment in the past year; (2) individuals reporting depressive symptoms within the past 2 weeks but not reporting treatment for depression in the past year, referred to as having ‘depressive symptoms’ and (3) a comparator group not treated for depression and without depressive symptoms. We included only sexually experienced participants, defined as those who reported having had one or more sexual partner by the time of their interview, because those reporting no previous sexual experience did not complete the CASI. We excluded from the analysis those reporting treatment from a healthcare professional in the past year for ‘any other mental health condition’ (12 men and 16 women).

Figure 1.

Proportional Venn diagrams showing the prevalence of ‘treatment for depression’ (i), and ‘depressive symptoms’ (ii) among men and women reporting one sexual partner, ever.

The CASI included a range of other questions, including those asking about having sex without condoms, paying for sex, concurrent sexual partnerships, self-appraisal of sex life and sexual health service use, including reported clinic attendance, use of emergency contraception, and testing for sexually transmitted infections (STI).20 Our assessment of sexual function used the Natsal-SF,26 a validated measure comprising components on problems with sexual response, sexual function in a relationship context and self-appraisal of sex life. Wherever possible, the timeframes used in the analysis were those closest to the time frame for reporting treatment for depression (past year) or depressive symptoms (past 2 weeks).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were carried out using the complex survey function of Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), accounting for the weighting, clustering and stratification of the Natsal-3 data. Survey weights were applied to adjust for unequal probability of selection and non-response to ensure the sample data were broadly representative of the British general population, according to the 2011 census, in terms of gender, age group and Government Office Region.20 21

We estimated the prevalence with 95% CIs of reporting treatment for depression and depressive symptoms, by demographic and health factors. Our approach to multivariable analysis was guided by consideration of the obvious confounders, and we have been careful not to ‘over-adjust’. We feel that only age can be said to have an ‘obvious’ association with the behavioural outcomes that would confound the associations presented in this paper. We therefore used binary and ordinal logistic regression models to calculate age-adjusted ORs (aAORs) to examine associations between treatment for depression, or depressive symptoms in the absence of treatment, relative to the comparator group (those not treated for depression and without depressive symptoms), and (1) risky sexual behaviours, (2) sexual function and (3) sexual health service use.

Results

Prevalence of depression

Among 13 507 sexually experienced Natsal-3 participants aged 16–74 years (5533 men and 7974 women), the estimated prevalence of having received ‘treatment for depression’ in the past year was 5.2% (95% CI 4.6% to 5.9%) in men and 11.8% (11.0% to 12.7%) in women (tables 1 and 2; figure 1). A further 6.7% (6.0% to 7.5%) of men and 6.4% (5.8% to 7.1%) of women had ‘depressive symptoms’ in the past 2 weeks but did not report treatment in the past year, while 1.8% (1.5% to 2.3%) of men and 3.9% (3.5% to 4.5%) of women reported treatment for depression and had depressive symptoms. In both men and women, treatment for depression was highest among those aged 35–64 years, whereas depressive symptoms were most common in those aged 16–24 years.

Table 1.

Variations in the prevalence of reporting treatment for depression and depressive symptoms by key demographic and health characteristics, men

| Men |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated and without depressive symptoms |

Treatment within the past year |

Depressive symptoms (without treatment) |

Unweighted, weighted denominator | ||||||

| Per cent | CI (%) | Per cent | CI (%) | aAOR* | Per cent | CI (%) | aAOR† | ||

| Overall | |||||||||

| 88.1 | (87.1 to 89.0) | 5.2 | (4.6 to 5.9) | – | 6.7 | (6.0 to 7.5) | – | 5533, 6789 | |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 16–24 | 88.1 | (86.1 to 89.9) | 2.6 | (1.8 to 3.7) | 1.00 | 9.3 | (7.7 to 11.1) | 1.00 | 1346, 984 |

| 25–34 | 88.5 | (86.5 to 90.2) | 4.4 | (3.4 to 5.6) | 1.66 (1.06 to 2.58) | 7.1 | (5.7 to 8.9) | 0.77 (0.56 to 1.05) | 1398, 1256 |

| 35–44 | 87.4 | (84.8 to 89.7) | 6.8 | (5.3 to 8.8) | 2.61 (1.65 to 4.15) | 5.8 | (4.2 to 7.8) | 0.63 (0.43 to 0.92) | 762, 1357 |

| 45–54 | 88.2 | (85.7 to 90.3) | 6.2 | (4.7 to 8.2) | 2.37 (1.47 to 3.80) | 5.5 | (4.1 to 7.4) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.87) | 728, 1316 |

| 55–64 | 85.3 | (82.2 to 87.9) | 6.9 | (5.2 to 9.1) | 2.73 (1.70 to 4.37) | 7.8 | (5.8 to 10.4) | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.26) | 698, 1097 |

| 65–74 | 92.4 | (89.9 to 94.3) | 2.8 | (1.8 to 4.3) | 1.01 (0.55 to 1.84) | 4.8 | (3.2 to 7.0) | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.78) | 601, 778 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||

| Living with a partner | 91.0 | (89.8 to 92.0) | 3.6 | (3.0 to 4.4) | 1.00 | 5.4 | (4.6 to 6.4) | 1.00 | 2912, 4628 |

| Steady relationship (not cohabiting) | 86.7 | (84.0 to 89.0) | 6.3 | (4.6 to 8.7) | 2.05 (1.35 to 3.09) | 7.0 | (5.3 to 9.0) | 1.26 (0.89 to 1.79) | 933, 748 |

| Previously in a live-in partnership | 73.8 | (70.3 to 77.1) | 15.5 | (12.7 to 18.6) | 5.21 (3.82 to 7.11) | 10.7 | (8.6 to 13.2) | 2.46 (1.81 to 3.34) | 754, 674 |

| Not in a steady relationship (never cohabited) | 85.0 | (82.2 to 87.5) | 4.5 | (3.2 to 6.3) | 1.54 (0.98 to 2.41) | 10.5 | (8.4 to 12.9) | 1.90 (1.34 to 2.69) | 894, 702 |

| Ended a cohabiting relationship, past year | |||||||||

| No | 88.8 | (87.8 to 89.7) | 4.7 | (4.1 to 5.4) | 1.00 | 6.5 | (5.8 to 7.3) | 1.00 | 5094, 6398 |

| Yes | 72.0 | (65.6 to 77.7) | 16.1 | (11.4 to 22.1) | 4.47 (2.93 to 6.83) | 11.9 | (8.2 to 17.0) | 2.14 (1.38 to 3.31) | 277, 237 |

| Sexual identity | |||||||||

| Heterosexual/straight | 88.4 | (87.4 to 89.3) | 5.0 | (4.4 to 5.6) | 1.00 | 6.6 | (5.9 to 7.4) | 1.00 | 5349, 6599 |

| Gay | 81.6 | (71.2 to 88.8) | 14.7 | (8.5 to 24.2) | 3.32 (1.75 to 6.30) | 3.8 | (1.3 to 10.5) | 0.60 (0.20 to 1.79) | 106, 102 |

| Bisexual | 70.7 | (56.1 to 82.1) | 10.8 | (5.2 to 21.0) | 2.74 (1.20 to 6.27) | 18.5 | (9.5 to 33.0) | 3.52 (1.56 to 7.94) | 61, 71 |

| Other | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13, 11 |

| Academic qualifications‡ | |||||||||

| No academic qualifications | 83.9 | (81.4 to 86.1) | 7.4 | (6.0 to 9.2) | 1.00 | 8.7 | (7.0 to 10.8) | 1.00 | 1153, 1509 |

| Academic qualifications typically gained at age 16 years | 87.9 | (86.1 to 89.4) | 5.7 | (4.6 to 6.9) | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.03) | 6.5 | (5.3 to 7.9) | 0.61 (0.43 to 0.85) | 1921, 2322 |

| Studying for/attained further academic qualifications | 90.2 | (88.8 to 91.5) | 4.0 | (3.2 to 4.9) | 0.50 (0.34 to 0.72) | 5.8 | (4.8 to 7.0) | 0.51 (0.37 to 0.72) | 2851, 3361 |

| Deprivation quintile | |||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 91.4 | (89.4 to 93.0) | 3.2 | (2.3 to 4.5) | 1.00 | 5.4 | (4.2 to 6.9) | 1.00 | 1096, 1428 |

| 2 | 90.9 | (88.8 to 92.7) | 3.9 | (2.7 to 5.4) | 1.21 (0.73 to 2.02) | 5.2 | (3.9 to 7.0) | 0.97 (0.64 to 1.47) | 1109, 1459 |

| 3 | 89.1 | (86.8 to 91.1) | 5.0 | (3.8 to 6.6) | 1.65 (1.04 to 2.61) | 5.8 | (4.4 to 7.7) | 1.10 (0.73 to 1.65) | 1081, 1320 |

| 4 | 85.9 | (83.3 to 88.1) | 6.2 | (4.8 to 7.9) | 2.16 (1.38 to 3.38) | 7.9 | (6.3 to 10.0) | 1.53 (1.04 to 2.25) | 1098, 1337 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 82.3 | (79.7 to 84.7) | 8.1 | (6.6 to 10.0) | 2.99 (1.95 to 4.58) | 9.5 | (7.7 to 11.7) | 1.91 (1.32 to 2.76) | 1149, 1245 |

| Self-reported health | |||||||||

| Fair/good/very good | 89.5 | (88.5 to 90.3) | 4.3 | (3.7 to 5.0) | 1.00 | 6.2 | (5.6 to 7.0) | 1.00 | 5338, 6545 |

| Bad/very bad | 52.0 | (43.9 to 59.9) | 29.4 | (23.1 to 36.7) | 12.07 (8.07 to 18.06) | 18.6 | (13.0 to 25.9) | 6.19 (3.85 to 9.95) | 193, 241 |

| Drink >6/8 units on one occasion—weekly | |||||||||

| No | 88.2 | (87.0 to 89.3) | 5.2 | (4.5 to 6.0) | 1.00 | 6.6 | (5.7 to 7.5) | 1.00 | 3969, 4997 |

| Yes | 88.6 | (86.6 to 90.4) | 5.0 | (3.8 to 6.4) | 0.97 (0.71 to 1.33) | 6.4 | (5.1 to 8.0) | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.24) | 1209, 1371 |

| Taken recreational drugs, past year | |||||||||

| No | 89.4 | (88.4 to 90.3) | 4.7 | (4.1 to 5.4) | 1.00 | 5.9 | (5.2 to 6.7) | 1.00 | 4426, 5746 |

| Yes | 80.8 | (77.7 to 83.5) | 8.2 | (6.5 to 10.4) | 2.47 (1.76 to 3.47) | 11.0 | (8.9 to 13.5) | 2.02 (1.50 to 2.71) | 1098, 1031 |

| Current cigarette smoker | |||||||||

| No | 89.9 | (88.8 to 91.0) | 4.0 | (3.4 to 4.8) | 1.00 | 6.0 | (5.2 to 7.0) | 1.00 | 3886, 4998 |

| Yes | 83.0 | (81.0 to 84.9) | 8.4 | (7.1 to 10.0) | 2.40 (1.83 to 3.14) | 8.5 | (7.2 to 10.1) | 1.48 (1.16 to 1.88) | 1647, 1791 |

All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, ever.

*OR for the outcome of reporting treatment for depression compared to not treated for depression—screened negative.

†OR for the outcome of reporting screened positive for depression compared to not treated for depression—screened negative.

‡Participants aged 17+ years.

aAOR, age-adjusted OR; NA, non-applicable due to too few participants.

Table 2.

Variations in the prevalence of reporting treatment for depression and depressive symptoms by key demographic and health characteristics, women

| Women |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated and without depressive symptoms |

Treatment within the past year |

Depressive symptoms (without treatment) |

Unweighted, weighted denominator | ||||||

| Per cent | CI (%) | Per cent | CI (%) | aAOR* | Per cent | CI (%) | aAOR† | ||

| Overall | |||||||||

| 81.7 | (80.7 to 82.7) | 11.8 | (11.0 to 12.7) | – | 6.4 | (5.8 to 7.1) | – | 7974, 6995 | |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 16–24 | 80.8 | (78.6 to 82.8) | 9.2 | (7.7 to 10.8) | 1.00 | 10.1 | (8.6 to 11.7) | 1.00 | 1688, 936 |

| 25–34 | 82.5 | (80.8 to 84.1) | 11.7 | (10.4 to 13.1) | 1.25 (1.00 to 1.57) | 5.8 | (4.8 to 6.9) | 0.56 (0.43 to 0.73) | 2315, 1278 |

| 35–44 | 80.5 | (77.9 to 82.8) | 13.6 | (11.7 to 15.8) | 1.49 (1.16 to 1.93) | 5.9 | (4.6 to 7.6) | 0.59 (0.43 to 0.82) | 1153, 1385 |

| 45–54 | 78.7 | (75.8 to 81.4) | 14.8 | (12.6 to 17.4) | 1.66 (1.28 to 2.17) | 6.4 | (5.0 to 8.4) | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.91) | 1044, 1364 |

| 55–64 | 83.0 | (80.4 to 85.4) | 12.0 | (10.0 to 14.3) | 1.28 (0.98 to 1.67) | 5.0 | (3.7 to 6.7) | 0.48 (0.33 to 0.70) | 967, 1167 |

| 65–74 | 86.7 | (83.9 to 89.1) | 7.2 | (5.5 to 9.4) | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.04) | 6.1 | (4.5 to 8.2) | 0.57 (0.40 to 0.80) | 807, 865 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||

| Living with a partner | 84.3 | (83.1 to 85.5) | 10.2 | (9.2 to 11.2) | 1.00 | 5.5 | (4.7 to 6.3) | 1.00 | 4306, 4647 |

| Steady relationship (not cohabiting) | 79.6 | (77.0 to 82.1) | 13.0 | (11.0 to 15.3) | 1.26 (1.00 to 1.59) | 7.3 | (5.9 to 9.2) | 1.26 (0.92 to 1.71) | 1341, 779 |

| Previously in a live-in partnership | 73.6 | (71.0 to 76.0) | 18.4 | (16.4 to 20.7) | 2.13 (1.77 to 2.57) | 8.0 | (6.6 to 9.6) | 1.75 (1.34 to 2.28) | 1558, 1108 |

| Not in a steady relationship (never cohabited) | 78.6 | (75.0 to 81.8) | 10.4 | (8.1 to 13.2) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.37) | 11.0 | (8.8 to 13.7) | 1.84 (1.35 to 2.50) | 719, 426 |

| Ended a cohabiting relationship, past year | |||||||||

| No | 82.3 | (81.3to 83.3) | 11.5 | (10.6to 12.4) | 1.00 | 6.2 | (5.6 to 6.9) | 1.00 | 7219, 6562 |

| Yes | 68.3 | (63.4 to 72.8) | 21.8 | (18.0 to 26.2) | 2.28 (1.76 to 2.96) | 9.9 | (7.0to 13.8) | 1.77 (1.18 to 2.67) | 484, 256 |

| Sexual identity | |||||||||

| Heterosexual/straight | 82.1 | (81.0 to 83.0) | 11.6 | (10.8 to 12.5) | 1.00 | 6.3 | (5.7 to 7.0) | 1.00 | 7731, 6811 |

| Gay | 72.7 | (61.0 to 82.0) | 16.1 | (9.1 to 27.1) | 1.56 (0.80 to 3.05) | 11.1 | (5.6 to 20.9) | 1.91 (0.88 to 4.12) | 85, 70 |

| Bisexual | 68.7 | (58.9 to 77.1) | 24.3 | (16.6 to 34.1) | 2.46 (1.50 to 4.04) | 7.0 | (4.0 to 11.8) | 1.15 (0.63 to 2.12) | 134, 90 |

| Other | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16, 15 |

| Academic qualifications‡ | |||||||||

| No academic qualifications | 77.1 | (74.6 to 79.4) | 14.9 | (13.0 to 17.0) | 1.00 | 8.0 | (6.6 to 9.8) | 1.00 | 1562, 1531 |

| Academic qualifications typically gained at age 16 years | 79.8 | (78.0 to 81.5) | 14.0 | (12.6 to 15.6) | 0.81 (0.66 to 1.01) | 6.2 | (5.2 to 7.3) | 0.61 (0.45 to 0.83) | 2851, 2509 |

| Studying for/attained further academic qualifications | 85.4 | (84.0 to 86.7) | 9.2 | (8.1 to 10.5) | 0.47 (0.37 to 0.60) | 5.4 | (4.6 to 6.3) | 0.45 (0.33 to 0.62) | 3957, 3261 |

| Deprivation quintile | |||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 86.4 | (84.4 to 88.1) | 8.9 | (7.4 to 10.6) | 1.00 | 4.7 | (3.7 to 6.0) | 1.00 | 1485, 1442 |

| 2 | 86.5 | (84.5 to 88.3) | 9.2 | (7.7 to 10.9) | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.36) | 4.3 | (3.3 to 5.6) | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.32) | 1564, 1456 |

| 3 | 83.6 | (81.3 to 85.6) | 10.1 | (8.6 to 11.9) | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.55) | 6.3 | (4.9 to 8.0) | 1.34 (0.94 to 1.93) | 1561, 1373 |

| 4 | 77.7 | (75.2 to 80.0) | 14.3 | (12.3 to 16.5) | 1.79 (1.37 to 2.33) | 8.0 | (6.6 to 9.7) | 1.83 (1.31 to 2.55) | 1650, 1389 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 73.9 | (71.4 to 76.2 | 17.2 | (15.2 to 19.3) | 2.27 (1.77 to 2.90) | 8.9 | (7.5 to 10.6) | 2.13 (1.53 to 2.95) | 1714, 1336 |

| Self-reported health | |||||||||

| Fair/good/very good | 83.4 | (82.4 to 84.4) | 10.6 | (9.8 to 11.4) | 1.00 | 6.0 | (5.4 to 6.6) | 1.00 | 7666, 6689 |

| Bad/very bad | 45.0 | (38.6 to 51.7 | 39.3 | (33.2 to 45.8) | 7.41 (5.48 to 10.01) | 15.6 | (11.5 to 21.0) | 5.89 (3.89 to 8.92) | 308, 305 |

| Drink >6/8 units on one occasion—weekly | |||||||||

| No | 82.5 | (81.4 to 83.5) | 11.3 | (10.4 to 12.2) | 1.00 | 6.3 | (5.6 to 7.0) | 1.00 | 6179, 5485 |

| Yes | 79.7 | (76.3 to 82.7) | 14.6 | (12.0 to 17.6) | 1.33 (1.05 to 1.70) | 5.7 | (4.1 to 7.9) | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.32) | 930, 766 |

| Taken recreational drugs, past year | |||||||||

| No | 82.3 | (81.3 to 83.3) | 11.3 | (10.5 to 12.2) | 1.00 | 6.3 | (5.7 to 7.0) | 1.00 | 7219, 6508 |

| Yes | 73.8 | (69.7 to 77.4) | 18.4 | (15.0 to 22.3) | 1.83 (1.39 to 2.41) | 7.8 | (6.1to 10.1) | 1.20 (0.88 to 1.62) | 738, 472 |

| Current cigarette smoker | |||||||||

| No | 84.0 | (82.9 to 85.0) | 10.0 | (9.1 to 10.9) | 1.00 | 6.0 | (5.3 to 6.8) | 1.00 | 5759, 5331 |

| Yes | 74.6 | (72.4 to 76.6) | 17.8 | (16.0 to 19.7) | 2.01 (1.71 to 2.36) | 7.7 | (6.5 to 9.0) | 1.38 (1.11 to 1.72) | 2215, 1664 |

All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, ever.

*OR for the outcome of reporting treatment for depression compared to not treated for depression—screened negative.

†OR for the outcome of reporting screened positive for depression compared to not treated for depression—screened negative.

‡Participants aged 17+ years.

aAOR, age-adjusted OR; NA, non-applicable due to too few participants.

Treatment for depression

After adjusting for age, treatment for depression was more common among men and women reporting a previous live-in partnership but currently single, and those currently in a non-cohabiting steady relationship (tables 1 and 2). There were 16.1% of men and 21.8% of women who reported ending a cohabiting relationship in the past year who had received treatment for depression in the same period, compared with 5.2% of men and 11.8% of women in the comparator group without depression (aAORs 4.47 (2.93 to 6.83) for men and 2.28 (1.76 to 2.96) for women). Treatment for depression was also more likely to be reported by those with lower academic attainment, those living in more deprived areas, as measured by area-level deprivation, and by men self-identifying as gay or bisexual, and by bisexual women.

Nearly one-third of men and nearly one-fifth of women self-reporting bad or very bad general health status reported treatment for depression, and the association remained strong after adjusting for age (aAORs 12.07 (8.08 to 18.06) for men and 7.41 (5.48 to 10.01) for women) (tables 1 and 2). Treatment for depression was also more likely among men and women who smoked and those who had taken recreational drugs in the past year. The association with binge drinking was less clear; for women only, treatment for depression was associated with reporting weekly consumption of six or more units of alcohol on any one occasion.

Sexual behaviour and STI risk

Men and women treated for depression reported fewer occasions of sexual activity in the past 4 weeks than the comparator group (table 3). After adjusting for age, reporting treatment for depression remained strongly associated with sexual behaviours that are markers for STI transmission. Treatment for depression was associated with reporting sex without condoms with two or more partners in the past year (aAOR 2.07 (1.38 to 3.10) in men and aAOR 2.22 (1.68 to 2.92) in women), and a same-sex partner in the past 5 years (aAOR 2.70 (1.57 to 4.62) in men and aAOR 2.02 (1.44 to 2.83) in women). In women, treatment for depression was also associated with partnership concurrency in the past 5 years (aAOR 2.01 (1.59 to 2.55)), the perception that a partner had had sex with someone else in the past 5 years (aAOR 1.55 (1.28 to 1.86)), and a higher self-perceived risk of STIs (aAOR 1.99 (1.26 to 3.15)).

Table 3.

Sexual behaviour and STI risk in those reporting treatment for depression, by gender

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | |

| Unweighted, weighted denominator | 4809, 5981 | 319, 353 | 6413, 5718 | 1012, 828 |

| 2+ heterosexual/same-sex occasions of sexual intercourse, past 4 weeks* | ||||

| Per cent | 68.7 | 55.9 | 66.1 | 57.7 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.79) | 1.00 | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.58 (0.43 to 0.80) | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.56 to 0.82) |

| 2+ heterosexual partners, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 15.1 | 18.0 | 8.7 | 13.4 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.71) | 1.00 | 1.63 (1.32 to 2.01) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.48 (1.05 to 2.09) | 1.00 | 1.90 (1.52 to 2.38) |

| Same-sex partner, past 5 years | ||||

| Per cent | 2.5 | 6.3 | 2.8 | 5.4 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.59 (1.52 to 4.41) | 1.00 | 1.94 (1.39 to 2.70) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.70 (1.57 to 4.62) | 1.00 | 2.02 (1.44 to 2.83) |

| 2+ heterosexual/same-sex partners without using a condom, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 7.4 | 12.2 | 4.4 | 8.0 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.74 (1.18 to 2.57) | 1.00 | 1.90 (1.46 to 2.48) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.07 (1.38 to 3.10) | 1.00 | 2.22 (1.68 to 2.92) |

| Paid for heterosexual/same sex, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 1.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.11 (0.76 to 5.89) | NA | NA |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.11 (0.76 to 5.92) | NA | NA |

| Concurrent partnerships, past 5 years | ||||

| Per cent | 15.0 | 16.9 | 7.1 | 12.0 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.83 to 1.60) | 1.00 | 1.79 (1.43 to 2.25) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.27 (0.90 to 1.78) | 1.00 | 2.01 (1.59 to 2.55) |

| Know/ perceive their most recent partner had sex with someone else, past 5 years† | ||||

| Per cent | 22.8 | 28.5 | 22.2 | 30.6 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.91) | 1.00 | 1.55 (1.28 to 1.87) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.36 (0.95 to 1.93) | 1.00 | 1.55 (1.28 to 1.87) |

| Diagnosed with a STI, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.34 (0.44 to 4.07) | 1.00 | 1.33 (0.72 to 2.44) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.80 (0.59 to 5.54) | 1.00 | 1.58 (0.86 to 2.90) |

| Self-perceived risk of STI: Quite a lot or greater | ||||

| Per cent | 3.4 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 3.9 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.69 to 2.09) | 1.00 | 1.93 (1.22 to 3.03) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.34 (0.77 to 2.35) | 1.00 | 1.99 (1.26 to 3.15) |

All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, ever (denominators may vary across variables due to item non-response).

Bold typeface highlights results where the confidence intervals exclude 1.0.

*Denominator restricted to those reporting at least one heterosexual or same-sex partner in the last year (men: not treated and without depressive symptoms—48 095 981; treated for depression—319 353; women: not treated and without depressive symptoms—64 135 718; treated for depression—1 012 828).

†Denominator restricted to those reporting a sexual partnership in the past 5 years (Men: Not treated and without depressive symptoms – 3955, 3912; Treated for depression – 241, 197 | Women: Not treated and without depressive symptoms – 5273, 3657; Treated for depression – 824, 465).

aAOR, age-adjusted OR; STI, sexually transmitted infections; NA, non-applicable due to too few participants.

Sexual function

Among those with at least one sexual partner in the past year (5054 men and 7332 women), individuals reporting treatment for depression were much more likely, after adjusting for age, than those without any depression to have ‘low sexual function’ as measured using the Natsal-SF score: for men treated for depression, the aAOR was 2.55 (1.85 to 3.52) and in women was 2.64 (2.16 to 3.23).

Among those treated for depression, 29.5% of men and 22.4% of all women reported being dissatisfied with their sex life, compared to 15.1% of men and 11.2% of women without depression, and the association remained after adjusting for age (table 4). There were strong associations between depression and other specific indicators of low sexual function, and the adjusted ORs were of similar magnitude when comparing men and women across the different variables. We found similar associations between depression and lacking interest in sex, and having trouble reaching orgasm. In all cases, the associations were not affected by adjusting for age (data shown) or relationship status (data not shown).

Table 4.

Sexual function of those reporting treatment for depression, by gender

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | |

| Unweighted, weighted denominator | 4750, 5914 | 314, 348 | 6334, 5650 | 998, 814 |

| Lowest quintile of sexual function (ref) | ||||

| Per cent | 17.3 | 34.8 | 16.2 | 33.1 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.55 (1.85 to 3.51) | 1.00 | 2.55 (2.09 to 3.12) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.55 (1.85 to 3.52) | 1.00 | 2.64 (2.16 to 3.23) |

| Components of the Natsal-SF score* (ref) | ||||

| Have experienced problems, for 3+ months, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 39.3 | 62.1 | 46.7 | 68.5 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.54 (1.86 to 3.45) | 1.00 | 2.48 (2.06 to 3.00) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.53 (1.85 to 3.45) | 1.00 | 2.52 (2.09 to 3.04) |

| Lacked interest in having sex, for 3+ months, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 13.0 | 29.0 | 30.0 | 50.9 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.74 (1.95 to 3.87) | 1.00 | 2.42 (2.02 to 2.91) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.74 (1.94 to 3.86) | 1.00 | 2.46 (2.05 to 2.96) |

| No orgasm or took a long time to reach orgasm despite arousal, for3+ months, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 8.2 | 20.0 | 14.2 | 24.9 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.80 (1.91 to 4.12) | 1.00 | 2.00 (1.62 to 2.48) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.80 (1.90 to 4.12) | 1.00 | 2.00 (1.61 to 2.48) |

| Trouble achieving/maintaining erections, for 3+ months, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 12.2 | 20.0 | ||

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.80 (1.22 to 2.66) | ||

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.86 (1.25 to 2.78) | ||

| Disagree/ disagree strongly to the statement: “I feel satisfied with my sex life" | ||||

| Per cent | 15.1 | 29.5 | 11.2 | 22.4 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.35 (1.76 to 3.14) | 1.00 | 2.28 (1.88 to 2.77) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.32 (1.74 to 3.11) | 1.00 | 2.30 (1.89 to 2.79) |

| Perceive a health condition/disability has affected sexual activity/enjoyment, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 13.5 | 45.7 | 12.8 | 36.7 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 5.40 (4.10 to 7.09) | 1.00 | 3.94 (3.31 to 4.70) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 5.74 (4.29 to 7.68) | 1.00 | 3.96 (3.32 to 4.72) |

| Perceive medications taken have limited sexual activity/enjoyment, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 6.2 | 36.5 | 3.8 | 24.5 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 8.69 (6.39 to 11.82) | 1.00 | 8.15 (6.44 to 10.31) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 10.28 (7.22 to 14.63) | 1.00 | 8.15 (6.44 to 10.31) |

| Taken any medicine/pills to assist sexual performance, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 6.2 | 10.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.80 (1.16 to 2.80) | 1.00 | 2.54 (1.33 to 4.88) |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.77 (1.12 to 2.81) | 1.00 | 2.62 (1.39 to 4.93) |

All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, ever (denominators may vary across variables due to item non-response).

Bold typeface highlights results where the confidence intervals exclude 1.0.

*All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, past year.

aAOR, age-adjusted ORo; Natsal, National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles.

There were strong associations between treatment for depression and reporting that a health condition had affected sexual activity, although we do not know whether the condition was depression. Similarly, 36.5% of men and 24.5% of women who reported taking medications that had limited their sexual activity also reported treatment for depression (aAORs 10.28 (7.22 to 14.63) for men and 8.15 (6.44 to 10.31) for women) (table 4). Those treated for depression were more likely to report taking drugs to assist their sexual performance (aAORs 1.77 (1.12 to 2.81) for men and 2.62 (1.39 to 4.93) for women).

Use of sexual health services

For men, although there was no association between reporting treatment for depression and sexual health clinic attendance in the past year, those treated for depression were more likely to report a recent chlamydia test (aAOR 1.92 (1.15 to 3.20), and to have sought help regarding their sex life in the past year from a healthcare professional (aAOR 2.92 (1.98 to 4.30) (table 5). The source of professional help was their GP/family doctor for 70% of these men, a psychiatrist/psychologist for 20%, and another healthcare provider for 10%.

Table 5.

Sexual health service use of those reporting treatment in the past year, by gender

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | Not treated and without depressive symptoms | Treatment within the past year | |

| Unweighted, weighted denominator | 4809, 5981 | 319, 353 | 6413, 5718 | 1012, 828 |

| Attended a sexual health (GUM) clinic, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 4.2 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.51 to 1.73) | 1.00 | 1.91 (1.42 to 2.58) |

| AOR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.64 (0.33 to 1.25) | 1.00 | 1.60 (1.15 to 2.24) |

| Had a chlamydia test, past year† | ||||

| Per cent | 15.6 | 18.0 | 25.1 | 25.7 |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.92 (1.15 to 3.20) | 1.00 | 1.27 (1.01 to 1.60) |

| AOR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.67 (0.97 to 2.89) | 1.00 | 1.18 (0.93 to 1.49) |

| Had a blood test for HIV, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 3.4 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 4.5 |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.16 (0.65 to 2.10) | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.27) |

| AOR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.50 to 1.84) | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.63 to 1.18) |

| You or your partner used emergency contraception, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.52 to 2.61) | 1.00 | 1.98 (1.23 to 3.19) |

| AOR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.45 to 2.26) | 1.00 | 1.71 (1.07 to 2.74) |

| Sought professional help regarding your sex life, past year | ||||

| Per cent | 6.4 | 16.6 | 5.7 | 12.5 |

| aAOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.92 (1.98 to 4.30) | 1.00 | 2.36 (1.83 to 3.04) |

| AOR* (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.89 (1.95 to 4.28) | 1.00 | 2.36 (1.83 to 3.04) |

All participants who have had at least one opposite-sex or same-sex partner, ever (denominators may vary across variables due to item non-response).

Bold typeface highlights results where the confidence intervals exclude 1.0.

*Adjusted for age and 2+ partners without using a condom, past year.

†Participants aged 16–44 years.

aAOR, age-adjusted OR; GUM, genitourinary medicine.

Women treated for depression were more likely to report attending a sexual health clinic (aAORs 1.91 (1.42 to 2.58)), having a recent chlamydia test (aAOR 1.27 (1.01 to 1.60)), and use of emergency contraception in the past year (aAOR 1.98 (1.23 to 3.19), and were also more likely to have sought professional help regarding their sex life (aAOR 2.36 (1.83 to 3.04)). GPs/family doctors were the source of sexual advice in 70% of these women, and a sexual health clinic, psychiatrist/psychologist or relationship counsellor were each reported by 10%.

Depressive symptoms

In a second analysis, using the same statistical approach, we investigated the sexual health of participants reporting depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks, but not treatment in the previous year. Compared to those reporting treatment for depression, the overall patterns of associations were similar for individuals with depressive symptoms, although the strength of associations was generally weaker, except for sexual function, where the associations were of a similar magnitude (see online supplementary appendix tables 1–3). Some differences were noted for men reporting depressive symptoms; for example, we observed significant associations with reporting of current partnerships, with the perception that a partner had had sex with someone else in the past 5 years, and with a higher self-perceived risk of STIs; associations that were not significant for men reporting treatment for depression. On the contrary, there were not associations for health service use for men, and only an association with seeking professional help for women with depressive symptoms.

bmjopen-2015-010521supp.pdf (116KB, pdf)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This study investigated the sexual health of people with a history of treatment for depression or depressive symptoms in a representative sample of the sexually experienced British general population aged 16–74 years. Individuals treated for depression, or with depressive symptoms, were more likely to report a range of sexual health difficulties. Those treated for depression were more likely to report behaviours linked to STI acquisition and/or transmission27 and depression was also strongly associated with low sexual function among men and women. For example, around two-thirds of those treated for depression reported problems with their sex lives, but only around 15% had sought professional help (and in most cases this was their GP/family doctor). Age adjustment made little difference to these findings, suggesting that these problems are experienced at all ages. Women treated for depression, but not men, were more likely to report accessing sexual health clinics, suggesting that depressed men in particular might be inadequately served by sexual health services.

We observed similar associations for a second group in the population, those with current depressive symptoms but no history of being treated for depression in the past year, for whom there was also evidence of being at greater risk of STIs, and having worse sexual function. This group is likely to include individuals with unmet mental health needs, who might be readily identifiable within a clinic population using the PHQ-2 screening tool. It was noticeable that this group was not more likely than those without reported symptoms or treated depression to use health services, suggesting coexiting unmet needs of mental health and sexual health.

These data provide valuable information to GPs, as well as to sexual health specialists, which may be used to improve the sexual health of patients with depression.

Comparison with other studies

Our study is unique in taking a broad-based approach to understanding the relationship between depression and sexual health at a general population level across the life course, and considering three key components of sexual health in people with depression: behaviour, function and health service use. This study considerably extends our previous work, where we showed that poor health, including depression, is independently associated with reduced sexual well-being at all ages in Britain.23 28 Other studies have reported on behaviour and function in isolation, and not considered service use. There is good evidence to suggest that depression is associated with increased sexual risk-taking in adolescent populations in North America. For example, the US National Longitudinal Adolescent Health Study found that depression was associated with reporting multiple partners, but was not associated with condom use (key to STI transmission),9 but there is a lack of consensus about the direction of association.29 30 Two studies are noteworthy in adult populations, again from North America. Pratt et al, found associations in US women aged 20–59 years between depressive symptoms (scored using the nine-question PHQ-9) and age at first sex, numbers of sexual partners in the past year, and infection with Herpes Simplex Virus-2, but there were no associations in men.12 Chen et al,13 used a 27-question approach to determine major depressive episodes in the past 12 months in a sample of Canadians aged 15–49 years, and found an association between a history of STIs and depressive symptoms in women and men younger than 35 years. By contrast, our study focuses on a group reporting clinical treatment, and found associations in both men and women across the life course. The differences in our findings might, in part, be due to our survey methodology, which has been specifically designed, with refinement over two decades, to collect the most accurate data about sensitive sexual behaviours.

Other surveys in the UK have shown that mental health symptoms are predictive of impaired sexual interest and function in men and women,31 and a recent systematic review also made this link.32 Studies in which partners have been included confirm the poorer sexual function, at least in men,33 who report fewer and weaker nocturnal erections.34 The likely mechanisms behind these associations are complex. They include a cognitive bias where depressed people experience lower satisfaction with sex as well as other activities;35 higher risk of metabolic syndrome in depressed people with the cardiovascular sequelae including sexual dysfunction;36 neuroendocrine changes, and the effects of treatment.37 Up to two-thirds of people treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors report sexual side effects,38 and such side effects are often a reason for ceasing to take the medication. Furthermore, antidepressants are often prescribed off-license to treat premature ejaculation, and their inhibitory sexual effects are well known.39 Our findings were striking in the strength of associations seen for reduced sexual function, and the high proportion reporting that health conditions and medications had affected their sex lives. This extended to specific symptoms, and we found that more than three in five men, and more than two in three women reporting treatment for depression had also experienced sexual problems for more than 3 months in the past year. Our study is also unique in including sexual health associations for a group reporting depressive symptoms but no treatment. We observed similar proportions of those reporting depressive symptoms but no treatment had experienced sexual problems, which suggests that depression rather than its treatment is more important in driving this association.

We know that individuals with sexual health problems often do not seek help,40 41 and we also know that attending specialist sexual health clinics can evoke a range of psychological symptoms and concerns.42 However, there are few data available addressing the important question about use of sexual health service in people with depression, and our study adds substantially to the literature in this respect.

Implications for policy and practice

Most depression is managed in primary care,2 and most people with sexual function problems initially seek professional help from their family doctor.43 In Britain, many sexual health services are being moved into community and other primary care settings, which provides an opportunity to align these areas of healthcare.44 45 We have considered two groups of individuals who may present to primary care, those receiving treatment for depression and those with depressive symptoms but not recently treated, and we observed evidence of poor sexual health in both. Depressed patients may therefore derive benefit from holistic assessment of sexual health and mental health,9 and by extension, appropriate and successful treatment of depression might reduce sexual risk-taking, and improve sexual function.

Our finding that men identifying as gay, and those reporting same-sex partners, and women identifying as bisexual and those reporting same-sex partners, were more likely to report treatment for depression, is consistent with the literature on lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people,46–49 who are at higher risk of mental ill health than heterosexuals, and these data support the need for policies that recognise coexisting health inequalities in LGB groups.50 Similarly, we found a strong association between reporting recent relationship breakup and treatment for depression, highlighting the need to consider relationship context in assessing patients’ mental health, and for proactive clinical management, which might include referral to counselling organisations like ‘Relate UK’. Depression was also more common in our study among another potentially vulnerable group, women reporting use of emergency contraception, which is an event that has been associated with depression in poor urban women, while the adverse outcome of unplanned pregnancy is a known threat to mental health.51–55 In the UK, women may readily obtain emergency contraception in pharmacies, where the capacity to assess mental health needs is likely to be limited by training and facilities to ensure confidentiality. Women accessing emergency contraception may, therefore, be in particular need of care in this respect, but research and policy are lacking in this area.

Our study is also relevant to sexual health practitioners; not only is the prevalence of mental health disorders high among patients attending sexual health clinics, but patients are more likely to reattend if staff recognise their psychological problems.5 Although the British Medical Association has called for greater importance to be given to mental health, and advocates for a holistic approach to care,56 the latest UK national guideline on consultations requiring sexual history-taking fails to emphasise mental health as an important comorbidity in patients requiring sexual healthcare.57 There are already pilot schemes, such as ‘Headspace’ in Australia, where mental and sexual health services have established collaborative partnerships to ensure full sexual health assessments, advice, treatment and referral as appropriate for clients.58 Our data support such integrated approaches to managing mental health and sexual health problems in primary care as well as specialist settings. Interventional studies might be required to understand whether such integrative approaches are a benefit to patients.

Overall, this study gives family doctors, who may be better placed to make links between services than other healthcare professionals, much needed information for understanding and improving the sexual health of patients treated for depression, and provides evidence to support the design of integrated approaches to managing patients with overlapping sexual and mental health needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants; the team of interviewers from NatCen Social Research who did the interviews; Heather Wardle, Vicki Hawkins, Cathy Coshall, and operations and computing staff from NatCen Social Research; and Kirsten Gravningen for valuable comments on drafts of the report.

Footnotes

Contributors: NF, PP, CHM, GR, MK, JAC, KRM and PS conceived the article. NF wrote the first draft of the article, with further contributions from PP, CHM, GR, MK, JAC, CT, LH, KRM, SC, JD, KW, AMJ and PS. PP did statistical analyses, with support from CHM and NF. CHM, PS, KW and AMJ, initial applicants for Natsal-3, wrote the study protocol and obtained funding. NF, CHM, PS, CT, SC, KRM, JD, KW and AMJ designed the Natsal-3 questionnaire, applied for ethics approval, and undertook piloting of the questionnaire. SC was responsible for data collection and delivery. CHM, CT, SC and PP managed data. All authors contributed to data interpretation, reviewed successive drafts, and approved the final version of the report.

Funding: Natsal-3 is a collaboration between University College London (London, UK), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, UK), NatCen Social Research, Public Health England (formerly the Health Protection Agency), and the University of Manchester (Manchester, UK). The study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (G0701757) and the Wellcome Trust (084840), with contributions from the Economic and Social Research Council and Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Natsal-3 study was approved by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A (reference: 09/H0604/27). Participants provided oral informed consent for interviews.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: An anonymised Natsa-3 dataset has been deposited with the UK Data Service, persistent identified: 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7799–1. Researchers are also directed to the Natsal website for further information (http://www.natsal.ac.uk).

References

- 1.Depression in adults: recognition and management. NICE guidelines [CG90] 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 [PubMed]

- 2.Airey C, Boreham R, Erens B, et al. 2003. National Survey of NHS patients, General Practice 2002. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/PublishedSurvey/NationalsurveyofNHSpatients/GPsurvey1999–2002/DH_4001356.

- 3.Goldberg D. A bio-social model for common mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994;90:66–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05916.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornicroft G, Sartorius N. The course and outcome of depression in different cultures: 10-year follow-up of the WHO Collaborative Study on the Assessment of Depressive Disorders. Psychol Med 1993;23:1023–32. 10.1017/S0033291700026489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborn DPJ, King MB, Weir M. Psychiatric health in a sexually transmitted infections clinic: effect on reattendance. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:267–72. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00299-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:849–57. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00304-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramrakha S, Caspi A, Dickson N et al. . Psychiatric disorders and risky sexual behaviour in young adulthood: cross sectional study in birth cohort. BMJ 2000;321:263–6. 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Beardslee WR. Temporal associations between depressive symptoms and self-reported sexually transmitted disease among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:599–606. 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan MR, Kaufman JS, Pence BW et al. . Depression, sexually transmitted infection, and sexual risk behavior among young adults in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:644–52. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waller MW, Hallfors DD, Halpern CT et al. . Gender differences in associations between depressive symptoms and patterns of substance use and risky sexual behavior among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:139–50. 10.1007/s00737-006-0121-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S et al. . Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics 2006;118:189–200. 10.1542/peds.2005-1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratt LA, Xu F, McQuillan GM et al. . The association of depression, risky sexual behaviours and herpes simplex virus type 2 in adults in NHANES, 2005–2008. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88:40–4. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Wu J, Yi Q et al. . Depression associated with sexually transmitted infection in Canada. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:535–40. 10.1136/sti.2007.029306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guirao Sánchez L, García-Giralda Ruiz L et al. . [Erectile dysfunction in primary care as possible marker of health status: associated factors and response to sildenafil]. Aten Primaria 2002;30:290–6. 10.1016/S0212-6567(02)79030-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suija K, Kerkelä M, Rajala U et al. . The association between erectile dysfunction, depressive symptoms and testosterone levels among middle-aged men. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:677–82. 10.1177/1403494814545103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derogatis LR, Meyer JK, King KM. Psychopathology in individuals with sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:757–63. 10.1176/ajp.138.6.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC. Lifetime psychopathology in individuals with low sexual desire. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;174:646–51. 10.1097/00005053-198611000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy SH, Rizvi S. Sexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:157–64. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819c76e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erens B, Phelps A, Clifton S et al. . Methodology of the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:84–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erens B, Phelps A, Clifton S. The third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3): Technical report. National Centre for Social Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P et al. . Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the lifecourse and trends over time: findings from the British National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1781–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys 2015. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions2015_8theditionwithchanges_April2015_logo.pdf

- 23.Field N, Mercer CH, Sonnenberg P et al. . Associations between health and sexual lifestyles in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet 2013;382:1830–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003;327:1144–6. 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S et al. . Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:348–53. 10.1370/afm.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell KR, Ploubidis GB, Datta J et al. . The Natsal-SF: a validated measure of sexual function for use in community surveys. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:409–18. 10.1007/s10654-012-9697-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S et al. . Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from The National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1795–806. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61947-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell KR, Mercer CH, Ploubidis GB et al. . Sexual function in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet Lond Engl 2013;382:1817–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heger JP, Brunner R, Parzer P et al. . [Depression and risk behavior in adolescence]. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 2014;63:177–99. 10.13109/prkk.2014.63.3.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Predictors of multiple sexual partners from adolescence through young adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:491–7. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nazareth I, Boynton P, King M. Problems with sexual function in people attending London general practitioners: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003;327:423 10.1136/bmj.327.7412.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2012;9:1497–507. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds CF III, Frank E, Thase ME et al. . Assessment of sexual function in depressed, impotent, and healthy men: factor analysis of a Brief Sexual Function Questionnaire for men. Psychiatry Res 1988;24:231–50. 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thase ME, Reynolds CF III, Jennings JR et al. . Nocturnal penile tumescence is diminished in depressed men. Biol Psychiatry 1988;24:33–46. 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90119-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nofzinger EA, Thase ME, Reynolds CF III et al. . Sexual function in depressed men. Assessment by self-report, behavioral, and nocturnal penile tumescence measures before and after treatment with cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:24–30. 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130026005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein I. The mutually reinforcing triad of depressive symptoms, cardiovascular disease, and erectile dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:41F–5F. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00892-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monteiro WO, Noshirvani HF, Marks IM et al. . Anorgasmia from clomipramine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 1987;151:107–12. 10.1192/bjp.151.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekselius L, von Knorring L. Effect on sexual function of long-term treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depressed patients treated in primary care. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:154–60. 10.1097/00004714-200104000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper K, Martyn-St James M, Kaltenthaler E et al. . Interventions to treat premature ejaculation: a systematic review short report. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl 2015;19:1–180, v–vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brock G, Moreira ED, Glasser DB et al. , GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Sexual disorders and associated help-seeking behaviors in Canada. Can J Urol 2006;13:2953–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buvat J, Glasser D, Neves RC et al. . Sexual problems and associated help-seeking behavior patterns: results of a population-based survey in France. Int J Urol Off J Jpn Urol Assoc 2009;16:632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arkell J, Osborn DP, Ivens D et al. . Factors associated with anxiety in patients attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic: qualitative survey. Int J STD AIDS 2006;17:299–303. 10.1258/095646206776790097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walters K, Buszewicz M, Weich S et al. . Help-seeking preferences for psychological distress in primary care: effect of current mental state. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:694–8. 10.3399/bjgp08X342174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Health and Social Care Act 2012, c.7. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted.

- 45.Hind J. Commissioning Sexual Health services and interventions: best practice guidance for local authorities. UK Department of Health; 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/144184/Sexual_Health_best_practice_guidance_for_local_authorities_with_IRB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS et al. . A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:70 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baams L, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Dev Psychol 2015;51:688–96. 10.1037/a0038994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mercer CH, Prah P, Tanton C et al. . The sexual health & well-being of men who have sex with men (MSM): Evidence from Britain's National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Oral presentation (O8) at BASSH Spring Conference 2015, 1–3 June 2015, Royal Glasgow Concert Halls, Glasgow: Published abstract in Sex Transm Infect 2015;91(Suppl 1):A3 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052126.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Public Health England. Promoting the health and wellbeing of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/324802/MSM_document.pdf

- 51.Garbers S, Correa N, Tobier N et al. . Association between symptoms of depression and contraceptive method choices among low-income women at urban reproductive health centers. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:102–9. 10.1007/s10995-008-0437-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis J, Presser L, Malbon K et al. . An exploratory analysis of contraceptive method choice and symptoms of depression in adolescent females initiating prescription contraception. Contraception 2015;91:336–43. 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bennett IM, Culhane JF, McCollum KF et al. . Unintended rapid repeat pregnancy and low education status: Any role for depression and contraceptive use? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:749–54. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stidham Hall K, Moreau C, Trussell J et al. . Young women's consistency of contraceptive use — does depression or stress matter? Contraception 2013;88:641–9. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wellings K, Jones KG, Mercer CH et al. . The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy and associated factors in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet Lond Engl 2013;382:1807–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wise J. Mental health should be given as much weight as physical health, BMA says. BMJ 2014;348:g3128 10.1136/bmj.g3128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brook G, Bacon L, Evans C et al. . 2013 UK national guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking. Clinical Effectiveness Group British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25:391–404. 10.1177/0956462413512807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards CA, Britton ML, Jenkins L et al. . Including a client sexual health pathway in a national youth mental health early intervention service--project rationale and implementation strategy. Health Educ Res 2014;29:354–9. 10.1093/her/cyt154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010521supp.pdf (116KB, pdf)