Abstract

Objectives

To describe the potential workload for patients with multimorbidity when applying existing clinical practice guidelines.

Design

Systematic analysis of clinical practice guidelines for chronic conditions and simulation modelling approach.

Data sources

National Guideline Clearinghouse index of US clinical practice guidelines.

Study selection

We identified the most recent guidelines for adults with 1 of 6 prevalent chronic conditions in primary care (ie hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoarthritis and depression).

Data extraction

From the guidelines, we extracted all recommended health-related activities (HRAs) such as drug management, self-monitoring, visits to the doctor, laboratory tests and changes of lifestyle for a patient aged 45–64 years with moderate severity of conditions.

Simulation modelling approach

For each HRA identified, we performed a literature review to determine the potential workload in terms of time spent on this HRA. Then, we used a simulation modelling approach to estimate the potential workload needed to comply with these recommended HRAs for patients with several of these chronic conditions.

Results

Depending on the concomitant chronic condition, patients with 3 chronic conditions complying with all the guidelines would have to take a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 13 medications per day, visit a health caregiver a minimum of 1.2 to a maximum of 5.9 times per month and spend a mean (SD) of 49.6 (27.3) to 71.0 (34.5) h/month in HRAs. The potential workload increased greatly with increasing number of concomitant conditions, rising to 18 medications per day, 6.6 visits per month and 80.7 (35.8) h/month in HRAs for patients with 6 chronic conditions.

Keywords: Multimorbidity, Chronic disease, PRIMARY CARE, Practice guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study assessing the potential workload for patients with multimorbidity in applying clinical practice guidelines in terms of time, number of medications and number of visits, focusing on the six prevalent chronic conditions in primary care.

The data are based on a systematic assessment of guidelines and a literature review.

Time estimations are probably underestimated because we were not able to find estimates for specific health-related activities such as time spent buying and preparing medications.

Since we used US guidelines, our results may not be generalisable to all countries and all healthcare systems.

Introduction

Non-communicable chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases are major public health challenges.1 In the USA, about half of all adults have at least one chronic condition;2 these conditions are the main cause of poor health, disability and death, and account for most of the healthcare expenditures.3–5

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of chronic conditions, is becoming the norm in primary care settings.1 5 The prevalence of multimorbidity is increasing and now represents 23% in the general population and up to 65% in people aged 65 years and older.6 Furthermore, 55% of patients with a chronic condition have multimorbidities.6 The management of patients with multimorbidity is challenging. Indeed, most evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are constructed with a ‘single condition’ approach.7–9 Physicians are supposed to synthesise all guidelines developed for each individual condition when managing patients with multimorbidity. For example, following clinical practice guidelines, a hypothetical 78-year-old woman with five chronic conditions (osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, diabetes type 2, hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD) would be prescribed up to 12 separate medications, taken at 5 times during the day and should be engaged in 14 non-pharmacological activities.10

Thus, patients with multimorbidity deal with the burden of illness and also the burden of treatment, defined as the workload imposed by healthcare on patients and the effect this has on quality of life.11 12 Patient workload encompasses all demands in their lives for health-related activities (HRAs) such as scheduling and attending appointments, preventive care, drug management, self-monitoring, visits to the doctor, laboratory tests, changes of lifestyle and paperwork. For example, patients with type 2 diabetes managed with oral agents could spend 143 min daily in recommended self-care.13 To our knowledge, the potential workload related to applying the combination of these guidelines has never been evaluated.

This study aimed to describe the potential workload of HRAs in applying clinical practice guidelines for patients with multimorbidity in primary care settings.

Methods

To describe the potential workload in applying clinical practice guidelines to patients with multimorbidity, we selected six chronic conditions prevalent in a primary care setting: hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease (CHD), COPD, knee osteoarthritis and depression.6 Since the recommendations in guidelines are according to patient characteristics, we defined a specific patient profile for whom the guidelines would apply: a male 45–64 years old. We chose this patient profile because the prevalence of multimorbidities in this age group is >30.4% (95% CI 30.2% to 30.5%).6 Furthermore, people in this age group probably have more professional and family responsibilities. Thus, dealing with a heavy workload might increase their burden of treatment. We arbitrarily chose a male. For each condition, we considered it at a moderate stage. We arbitrarily chose that a patient with CHD or COPD was smoking and that a patient with knee osteoarthritis was overweight14 (see online supplementary appendix 1). Then, we searched the most recent clinical practice guidelines dedicated to the management of each condition, to a combination of two or more conditions, as well as to smoking cessation, overweight, immunisation and prevention services. From these guidelines, we extracted all HRAs (ie, medication, diet, education, physical exercise, self-monitoring, visits to care providers, complementary tests, etc) that were moderately and strongly recommended for the management of a moderately severe condition. Then, we performed a literature review to determine the potential workload in terms of time spent on each HRA. Finally, we estimated the potential workload needed to comply with these clinical practice guidelines for patients with 1–6 chronic conditions.

bmjopen-2015-010119supp.pdf (447.3KB, pdf)

Identification of clinical practice guidelines

We searched the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) (http://www.guideline.gov) to identify the most recent clinical practice guidelines for hypertension, diabetes, CHD, COPD, osteoarthritis, depression, smoking cessation, overweight, prevention services and immunisation. The NGC is a public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. We focused on this library because, to the best of our knowledge, it is the only library that systematically reviews guidelines, using a standardised process, before the guidelines are posted to the NGC website and indexed, which ensures their quality, and all guidelines are freely available. The search was performed on 14 June 2013 using the keywords ‘hypertension’, ‘diabetes’, ‘ischaemic heart disease’, ‘chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’, ‘osteoarthritis’ and ‘depression’, ‘smoking cessation’ and ‘overweight’. For prevention services, we used the advanced search feature with limitations to ‘family practice’ for clinical specialty; ‘middle age (45––64 years)’ for age of target population; and ‘counselling’, ‘risk assessment’, ‘prevention’ or ‘screening’ for guideline category.

One of us (CBV) screened the retrieved guidelines and selected the most recent guidelines dedicated to the management of each condition, their combination and prevention services. We excluded guidelines related to a specific setting (eg, Wisconsin guidelines) or population (eg, children, pregnancy), management of disease complications only (eg, acute coronary syndromes) or specific severity of disease (eg, management of microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus).

We retrieved the full text of all selected guidelines.

Extraction of HRAs

For each guideline, two reviewers (CBV and CB) independently extracted all HRAs that were moderately and strongly recommended for the management of the profile of patients defined previously with a moderate severe condition (appendix 1). According to the classification used in the NGC library, recommendations that mentioned a high quality of evidence were considered strongly recommended and recommendations that mentioned a moderate quality of evidence were considered moderately recommended. Any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. The agreement between the two reviewers was 73%. These HRAs were classified by two investigators (CBV and IB) under the following categories and we systematically recorded the following information:

Pharmacological treatments: we recorded the pharmacological class, route of administration, duration, frequency and dose per day, and drugs contraindicated; when several pharmacological treatments were proposed, we selected the treatment that provided the fewest burdens.

Supervised interventions such as exercise programme, counselling, self-management programme: we recorded the duration and frequency of the intervention.

Unsupervised behavioural interventions such as physical activity and diet.

Monitoring and follow-up recommended (ie, visit to health caregivers, complementary examinations, self-monitoring such as home-monitoring blood pressure): we recorded the frequency of the monitoring and follow-up recommended.

When a guideline provided recommendations on the management of the combination of different chronic conditions of interest, we recorded the HRA accordingly. When the intervention or the HRA was not sufficiently described in the guidelines, we searched for original publications describing the intervention in terms of duration and frequency. For this purpose, we retrieved all articles describing the intervention referenced in the guidelines. If none were referenced or if the retrieved articles did not provide sufficient information on the intervention, we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for systematic reviews dedicated to this intervention. When several interventions were described, we recorded the frequency and duration that was proposed most frequently or that provided the fewest burdens.

Treatments for acute exacerbation or intercurrent abnormalities and initial management of disease (eg, cardiac rehabilitation in CHD) were not considered.

Time spent on each recommended HRA

We searched the literature for studies providing an estimation of the time spent on HRAs and extracted the mean (SD) time spent for the different HRAs. If needed, we used formulas provided by Pudar Hozo15 to estimate the mean (SD) from the median, range and sample size. HRAs for which no estimation of their workload could be retrieved in the literature were not considered.

Simulation modelling approach of the potential workload for patients with several concomitant chronic conditions

We used a simulation modelling approach to estimate the potential workload for patients with multiple conditions. When the same type of HRA was recommended, we retained the HRA that recommended the greatest amount of time. We considered that visits to health caregivers were specific for each condition and that several blood tests could be performed in one visit.

We also systematically checked whether any HRA recommended for one chronic condition was not contraindicated for the associated chronic condition. The potential workload was expressed in terms of number of medications per day, number of visits to a health caregiver per month and time spent on HRAs in hours per month. We performed simulations to estimate the potential workload for a patient with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 concomitant conditions and in terms of overall time spent on HRAs in hours per month. We assumed skewed distributions of time for each HRA and hypothesised that time was a random variable with lognormal distribution. We used the parameters (mean, SD) for activities found by the literature review for data generation. We generated 1000 independent observations for each HRA, then added simulated observations to estimate the mean (SD) time spent for each patient multimorbidity profile and globally. Simulations involved use of SAS V.9.3 (SAS Inst, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Identification of clinical practice guidelines

Our search strategy identified six clinical practice guidelines, one for each selected condition, as well as one for smoking cessation, one for overweight, one for prevention and one for vaccination (appendix 2). We did not identify any clinical practice guidelines specifically dedicated to the management of the combination of the selected chronic conditions. However, all guidelines provided recommendations on the management of one potential concomitant conditions (appendix 3). For example, in the guideline dedicated to management of hypertension, recommendations are available for the following concomitant conditions: chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease or left ventricular hypertrophy, chronic heart failure, diabetes mellitus, depression and cardiovascular disease.

Extraction of HRAs

From these guidelines, we extracted 5 moderately and 51 strongly recommended HRAs (table 1, see online supplementary appendices 3 and 4). We recorded 8 HRAs for managing hypertension, 12 for diabetes, 13 for CHD, 7 for COPD, 6 for knee osteoarthritis, 4 for depression and 2 each for prevention, tobacco use and overweight. These HRAs consisted of pharmacological treatment (from 1 to 5 HRAs per condition), supervised intervention (from 1 to 2 HRAs per condition), unsupervised intervention (from 1 to 3 HRAs per condition) and monitoring and follow-up (from 1 to 4 HRAs per condition). Management of CHD involved the highest number of HRAs (n=13).

Table 1.

HRAs considered for each condition, with frequencies

| Pharmacological treatment |

Supervised intervention |

Unsupervised behavioural intervention |

Monitoring and follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRA | Frequency | HRA | Frequency | HRA | Frequency | HRA | Frequency | |

| Hypertension | Thiazide-type diuretics ACE inhibitors* (plus calcium-channel antagonist†) |

1/day 1/day |

Multidisciplinary team (educator, dietician) | 1/year | Diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet) Physical activity |

Daily 3/week |

Blood test 12-lead electrocardiography Physician appointment Home blood pressure monitoring‡ |

1/year 1/year 1/year 1/day |

| Diabetes | Statin Metformine ACE inhibitors* (plus calcium-channel antagonist†) Influenza vaccine Pneumococcal vaccine |

1/day 3/day 1/day 1/year 1/5 years |

Counselling with qualified professional Self-management |

1/year 1/year |

Diet Physical activity |

Daily 2/week |

Self-monitoring blood glucose Blood and urine tests Physician appointment Ophthalmologist |

2/years 1/year 1/year 1/year |

| CHD+tobacco consumption | β-blockers Aspirin Statin ACE inhibitors* Nicotine substitute Influenza vaccine |

1/day 1/day 1/day 1/day 2/day 1/year |

Individualised education Stop smoking: intensive counselling |

1/year 4/month |

Diet Physical activity |

Daily 1/day |

Blood test 12-lead-electrocardiography Physician appointment Radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or echocardiography or cardiac MRI |

1/year 1/year 1/year 1/2 years |

| COPD+tobacco consumption | Combination of long-acting bronchodilatators and inhaled corticosteroids Nicotine substitute Influenza vaccine Pneumococcal vaccine |

2/day 2/day 1/year 1/5 years |

Stop smoking: intensive counselling | 4/month | Physical activity | 1/day | Spirometry Physician appointment |

1/year 1/year |

| Depression | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 1/day | Physical activity | 3/week | Health caregiver (collaborative care approach) | 1/month | ||

| Knee osteorthritis+overweight | Acetaminophen or NSAIDs (included COX-2) or tramadol Topical NSAIDs Intra-articular corticosteroid injections |

3/day 2/day 3/year |

Education | 1/year | Cardiovascular aerobic and/or resistance land-based exercise Diet Use of thermal agents Walking aids |

5/week daily |

Physician appointment | 1/year |

| Prevention services | Influenza | 1/year | Occult blood testing or colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy | 1/5 year | ||||

*Use ACE inhibitors when CHD is associated with hypertension (instead of thiazide-type diuretics) or diabetes.

†Use ACE inhibitors and calcium-channel antagonist if hypertension is associated with diabetes.

‡Home blood pressure monitoring when hypertension is associated with diabetes.CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; HRAs, health-related activities; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Time spent on each recommended HRA

From the literature review,16–18 we estimated that the mean (SD) time spent taking medication was 2.0 (1.8) min, following a diet 49.4 (47.2) min, home monitoring 5.0 (2.8) min (eg, blood pressure or blood sugar), for physical activities 38.6 (44.7) min and for attending appointments 125.0 (111.0) min. No data were obtained on the workload for going to the drugstore and applying thermal agents to a painful joint for osteoarthritis. Consequently, we excluded these HRAs from further analysis. For supervised intervention sessions with no duration reported in the guidelines and for injections (immunisations or intra-articular corticosteroid injections), we considered that the duration was equivalent to the mean (SD) time spent for one appointment (ie, 125.0 (111.0) min).

Potential workload for patients with several concomitant chronic conditions

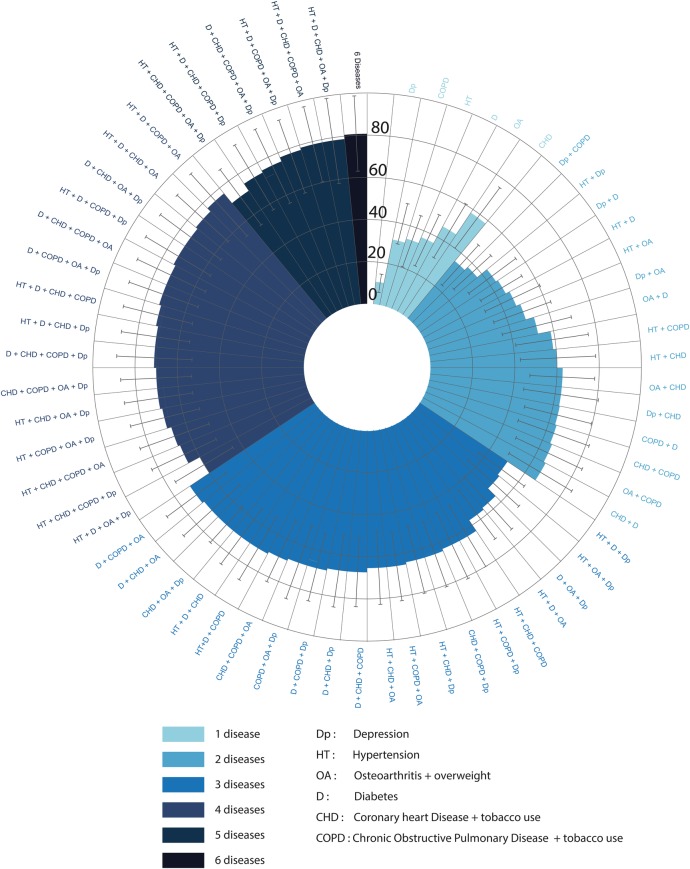

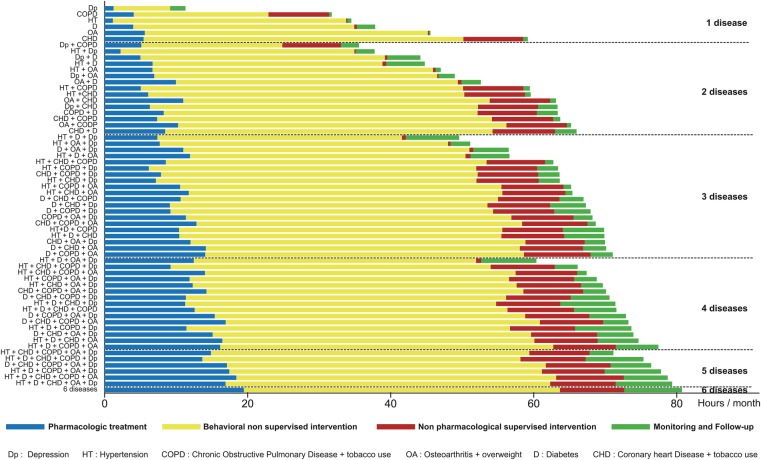

Table 2 and online supplementary appendix 5 describe the workload in terms of number of medications per days, number of visits per months and time spent per month for patients with one to six chronic conditions. Depending on the concomitant chronic conditions, patients with 3 chronic conditions complying with all the guidelines would have to take a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 13 medications per day, visit a health caregiver a minimum of 1.2 to a maximum of 5.9 times per month and spend a mean (SD) of 49.6 (27.3) to 71.0 (34.5) h per month on HRAs (appendix 5). Figures 1 and 2 represent the time spent by patients in HRAs (hours per month) by activity and multimorbidity profile. For example, a patient with hypertension, osteoarthritis and diabetes could spend a mean (SD) of 56.6 (29.2) h per month on HRAs, with 11.9 (10.2) h on pharmacological treatment, 38.5 (26.7) h on behavioural intervention, 0.7 (0.6) h on supervised intervention including education, and 5.5 (2.4) h on self-monitoring and follow-up. In this example, behavioural interventions included time dedicated to diet (25.0 h per month) and to physical activity (13.9 h per month), both recommended for these three conditions. Coronary heart disease could require the most time needed among the 6 selected chronic conditions, 59.2 (35.5) h per month, whereas depression could only require 11.3 (8.9) h per month.

Table 2.

Number of medications per day and visits to a health caregiver per month recommended in guidelines for adults

| Medications×per day |

Visits per month |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1–Q3 | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Q1–Q3 | Minimum | Maximum | |

| 1 condition (n=6) | 4 | (1–5) | 1 | 5 | 0.8 | (0.5–3.5) | 0.4 | 4.5 |

| 2 conditions (n=15) | 6 | (5–8) | 2 | 10 | 4.6 | (1.4–4.8) | 0.8 | 5.5 |

| 3 conditions (n=20) | 10 | (8–11) | 6 | 13 | 5.1 | (4.9–5.7) | 1.2 | 5.9 |

| 4 conditions (n=15) | 12 | (11–14) | 9 | 15 | 6.0 | (5.4–6.1) | 2.2 | 6.2 |

| 5 conditions (n=6) | 16 | (14–16) | 13 | 17 | 6.3 | (6.2–6.4) | 5.6 | 6.4 |

| 6 conditions (n=1) | 18 | 6.6 | ||||||

Q1–Q3, quartile 1–3.

Figure 1.

Time spent by patients in health-related activities (hours/month) by multimorbidity profile. CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D, diabetes; Dp, depression; HT, hypertension; OA, oesteoarthritis.

Figure 2.

Time spent by patients in health-related activities (hours/month) by activity and multimorbidity profile. CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D, diabetes; Dp, depression; HT, hypertension; OA, oesteoarthritis.

Behavioural interventions could require the most time per month among all HRAs, from 54.9% of the total time needed for a patient with the 6 selected conditions to 94.6% for a patient with only COPD. The most time needed for behavioural interventions should be for a patient with coronary heart disease (44.7 (34.4) h per month), whereas the time needed for a patient with depression could only require 7.9 (8.8) h per month. With the increased number of the 6 selected chronic conditions, time required for pharmacological treatment increased, from 3.3% of the total time needed for a patient with COPD to 24.1% for a patient with the 6 selected chronic conditions, whereas the proportion of time dedicated to supervised interventions and monitoring and follow-up remained stable.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the potential workload of applying clinical practice guidelines for patients with multimorbidity in terms of time, number of medications and number of visits, focusing on the six prevalent chronic conditions in primary care. According to the guidelines, patients with 3 chronic conditions need to take from 6 to 13 medications per day, visit a health caregiver 1.2 to 5.9 times per month and spend a mean of 49.6–71.0 h per month on HRAs. The potential workload increased greatly with increasing number of conditions, rising to 18 medications per day, 6.6 visits per month and 80.7 h per month for HRAs for patients with 6 chronic conditions. Knowing that, in the USA, the mean working time is 131 h per month and that the mean time dedicated to caring for and helping household members is 16 h per month,19 the potential time dedicated to HRAs would be onerous for these patients.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies; important differences in results

Consequences of the workload on patients' quality of life define the burden of treatment. This emerging concept is receiving increasing attention.12 20 Previous studies estimating the workload for patients focused on a given chronic condition such as diabetes.13 Other studies mainly explored the time actually spent by patients in HRAs and not the time they would spend if they strictly followed the moderate and strong recommendations of clinical practice guidelines. In a large survey, multimorbid patients with at least 2 chronic conditions declared spending a median of 5.2 to 16.5 h per month in HRAs.21 Our results are supported by other research on this topic showing that the application of current evidence-based guidelines for patients with multimorbidity is limited.10 22–24

Our study has several strengths. First, we systematically identified all existing guidelines, and two independent reviewers extracted all HRAs from these guidelines. Second, the workload of applying clinical practice guidelines for multimorbid patients in terms of time spent was estimated from a review of the literature and simulations. However, our study also has some limitations. First, our model considered only part of the burden of treatment. In fact, according to Gallacher et al,25 from normalisation process theory, the treatment burden for patients with multimorbidity includes the work needed to understand treatments, interact with others to organise care, attend appointments, take medications, alter lifestyle and appraise treatments.In our model, we did not take into account all these factors. Furthermore, we were not able to take into account the burden of the stress and discomfort resulting from following the guidelines, or adverse effects (eg, dizziness or fatigue from antihypertensives or hypoglycaemia from hypoglycaemic agents). Second, the time estimations are probably underestimated. Indeed, if time spent attending appointments includes the time needed to go to the medical centre and some of the waiting time, we may not have completely accounted for the additional time related to the completion of forms, difficulties with access and parking, time to buy medication and other activities. Diagnostic services are also under-represented in this model because we did not consider the time dedicated to the initial management of the condition or treatment of acute exacerbation or an intercurrent abnormality. Finally, the time might vary according to healthcare systems. For example, the lack of a single-payer system in the USA may increase the burden related to the large amount of administrative work needed to seek and obtain care for the patient. Furthermore, we accumulated times for each HRA without considering the possible interactions between HRAs (eg, 2 appointments in one) or between the condition and HRAs (eg, possible difficulties for a patient with knee osteoarthritis to go to an appointment). Finally, we focused on one age group (45–64 years) and six prevalent chronic conditions, so we cannot extrapolate our results to all patient profiles. In addition, because we used US guidelines, our results may not be generalisable to all countries and to all healthcare systems. However, the results are not likely to vary greatly.

Implications for clinicians and policymakers

Chronic conditions and multimorbidity are becoming the greatest epidemic in high-income countries. More than one-quarter of all adults have multiple chronic conditions,26 and nearly one-third of patients with multimorbidity are from 45 to 64 years old6 and have an average of three chronic conditions.9 Our findings highlight that existing clinical practice guidelines are not appropriate for managing multimorbidity. Complete adherence to these guidelines considering the workload involved for patients is not realistic.27 This workload will inevitably induce poor adherence, wasted resources and poor outcomes. We need a paradigm shift in planning research and elaborating clinical practice guidelines. We should move from the current ‘single-condition’ approach to developing clinical practice guidelines toward a patient-centred approach.28 29 Specific guidelines for all situations are probably not realistic. In fact, 57 different clinical practice guidelines would be required for the 6 chronic conditions we selected. In a patient-centred approach, guidelines would take into account patient choices and preferences, involving them in research or guideline elaboration.30 This approach would consider the burden of treatment12 31 and promote minimally disruptive medicine.20 For example, in the UK, the National Institute for health and Care Excellence (NICE) was asked to develop a clinical practice guideline on multimorbidity to define prioritisation and management of care for these patients. Finally, more research is needed to explore how to prioritise the recommendations from different clinical practice guidelines to patients' management.

In conclusion, we assessed the HRA workload needed to apply clinical practice guidelines for patients with multimorbidity who were 45 to 64 years old. The workload needed to follow the guidelines rapidly increased with increasing number of comorbidities. A new paradigm shift is needed to manage patients with multimorbidity to be less burdensome and more attainable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Smales for critical reading and English correction of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: CBV, CB and IB acquired and interpreted the data. CBV and GB analysed the data. CBV wrote the manuscript. All the authors were involved in drafting the manuscript All the authors were involved in drafting the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Alwan A. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA et al. . Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 2014;384:45–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA et al. . Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1836–41. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:177–86. 10.1001/jama.297.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S et al. . Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e12–21. 10.3399/bjgp11X548929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. . Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd CM, Vollenweider D, Puhan MA. Informing evidence-based decision-making for patients with comorbidity: availability of necessary information in clinical trials for chronic diseases. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e41601 10.1371/journal.pone.0041601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes LD, McMurdo MET, Guthrie B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing 2013;42:62–9. 10.1093/ageing/afs100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P et al. . Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e6341 10.1136/bmj.e6341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C et al. . Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients. JAMA 2005;294:716–24. 10.1001/jama.294.6.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eton DT, Oliveira D, Egginton J et al. . Understanding the burden of treatment in patients with multiple chronic conditions: evidence from exploratory interviews. Qual Life Res 2010;19:929–30. 10.1007/s11136-010-9684-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran VT, Montori VM, Eton DT et al. . Development and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditions. BMC Med 2012;10:68 10.1186/1741-7015-10-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell LB, Suh D-C, Safford MA. Time requirements for diabetes self-management: too much for many? J Fam Pract 2005;54:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J et al. . Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:329–35. 10.1002/art.24337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmchen LA, Lo Sasso AT. How sensitive is physician performance to alternative compensation schedules? Evidence from a large network of primary care clinics. Health Econ 2010;19:1300–17. 10.1002/hec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell LB, Ibuka Y, Carr D. How much time do patients spend on outpatient visits?: the American Time Use Survey. Patient 2008;1:211–22. 10.2165/1312067-200801030-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yen LE, McRae IS, Jowsey T et al. . Time spent on health related activity by older Australians with diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2013;12:33 10.1186/2251-6581-12-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey, 2012 Results [Internet] 2013. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/atus_06202013.pdf

- 20.May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ 2009;339:b2803 10.1136/bmj.b2803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jowsey T, McRae IS, Valderas JM et al. . Time's up. Descriptive epidemiology of multi-morbidity and time spent on health related activity by older Australians: a time use survey. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e59379 10.1371/journal.pone.0059379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Clancy C et al. . Current guidelines have limited applicability to patients with comorbid conditions: a systematic analysis of evidence-based guidelines. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e25987 10.1371/journal.pone.0025987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muth C, Kirchner H, van den Akker M et al. . Current guidelines poorly address multimorbidity: pilot of the interaction matrix method. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1242–50. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M et al. . Drug-disease and drug-drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ 2015;350:h949 10.1136/bmj.h949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM et al. . Understanding patients' experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:235–43. 10.1370/afm.1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho TH, Caughey GE, Shakib S. Guideline compliance in chronic heart failure patients with multiple comorbid diseases: evaluation of an individualised multidisciplinary model of care. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e93129 10.1371/journal.pone.0093129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome: a Cochrane Review. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:580–1. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.4190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parekh A, Kronick R, Tavenner M. Optimizing health for persons with multiple chronic conditions. JAMA 2014;312:1199–200. 10.1001/jama.2014.10181.Conflict [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muth C, van den Akker M, Blom JW et al. . The Ariadne principles: how to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med 2014;12:223 10.1186/s12916-014-0223-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mair FS, May CR. Thinking about the burden of treatment. BMJ 2014;349:g6680 10.1136/bmj.g6680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010119supp.pdf (447.3KB, pdf)