Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection is a common health problem related to many gastrointestinal disorders. This study aims to estimate the total and age specific prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori infection in Iran. We systematically reviewed all national and international databases and finally identified 21 studies were eligible for meta-analysis. Each of them were assigned a quality score using STROBE checklist. Due to significant heterogeneity of the results, random effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence and 95% confidence interval of Helicobacter Pylori infection. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA. V11 software. The pooled prevalence (95% confidence interval) of Helicobacter Pylori infection among all population, children and adults were estimated as 54% (53%- 55%), 42% (41%- 44%) and 62% (61%- 64%) respectively. Helicobacter Pylori, has infected more than half of Iranian people during the last decade. Preventive strategies as well as taking into account this infection during clinical visits should be emphasized to reduce its transmission and prevalence within the community.

Keywords: Helicobacter, Iran, meta-analysis, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori infection is one of the most important bacterial infections involved about 50% of the population worldwide.[1] Infection with this bacterium has been proved to be associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, metabolic syndrome, chronic gastritis, and other gastrointestinal disorders.[1,2]

This infection is more common in developing countries compare to developed communities. Different studies have been conducted in many countries, reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection from <20% in European countries[3] to more than 80% in some Eastern Mediterranean countries.[1] Such variations in the estimated prevalence rates were also observed in the studies carried out in Iran.[1,2]

Different parts of Iran have different prevalence rates of H. pylori infection.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] To implement national strategies for control or eradication of this infection, it is necessary to have a pooled estimate of H. pylori infection within the whole country. Meta-analysis is a complex of statistical methods used to combine the results of primary studies. This summarization of the results can increase the accuracy and power of the study because the estimation was performed in a larger sample size.[19,20]

Some systematic review/meta-analyses were carried out in Iran to estimate the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection. These meta-analyses used primary studies with different sampling methods such as random, symptomatic individuals and patients as well as health staffs. In the current study, we aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of H. pylori infection combining only the results of the studies used representative samples of populations. We also entered more recent studies and adjusted the results according to their quality to decrease the potential biases.

METHODS

Search strategy

This study was a systematic review and meta-analysis of the H. pylori infection prevalence in Iran. All data was collected from the studies estimated this prevalence among general population selecting random sampling methods. We systematically searched all national (Magiran, SID, IranMedex, Medlib) and International (Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct) databases. To prevent potential biases, searching databases as well as data extraction were carried out by two independent researchers (Afshari, Moosazadeh). Search strategy was performed using the following keywords or their Farsi equivalents:

“H. pylori,” “Helicobacter,” “Helicobacter pylori,” “general population,” “children,” “adults,” “prevalence,” “seroprevalence,” “seroepidemiology,” “serology,” “Iran”.

In the first step, titles and abstracts of the primary selected articles were reviewed. Then, we reviewed the full texts of the papers identified during the first step and found more relevant articles. In order to increase the search sensitivity, we investigated references within the papers and found some relevant papers. Finally, we assessed the quality of the final selected papers using STROBE checklist.[21] During this step, all papers were dedicated a quality score from 0 to 22 and entered into the meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria

All papers identified eligible during the multiple phases of the systematic search estimating the prevalence of H. pylori infection among Iranian population.

Excluding criteria

Studies conducted by case–control or experimental design or those conducted among nonrandomly selected populations such as patients, health workers, and endoscopic samples.

Data extraction

All required information such as author name, date of study conduction, total prevalence of H. pylori infection, age and gender-specific prevalences, method of diagnosis, study sample size, P value indicating the significance of the difference between genders and age groups, and mean age of the participants were extracted by complete review of the eligible articles.

Statistical analysis

The standard error of the prevalence rate in each study was calculated according to the binomial distribution. We used Cochrane Q-test as well as Tau square index to assess the heterogeneity of results. Because of the significant heterogeneity, a random-effect model was applied to combine the prevalence rates. To estimate the difference of prevalences between genders and age groups, P value meta-analysis method was used. P < 0.05 was considered significant. To investigate the effect of age, gender, diagnostic method, and date of the study, meta-regression models were used. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

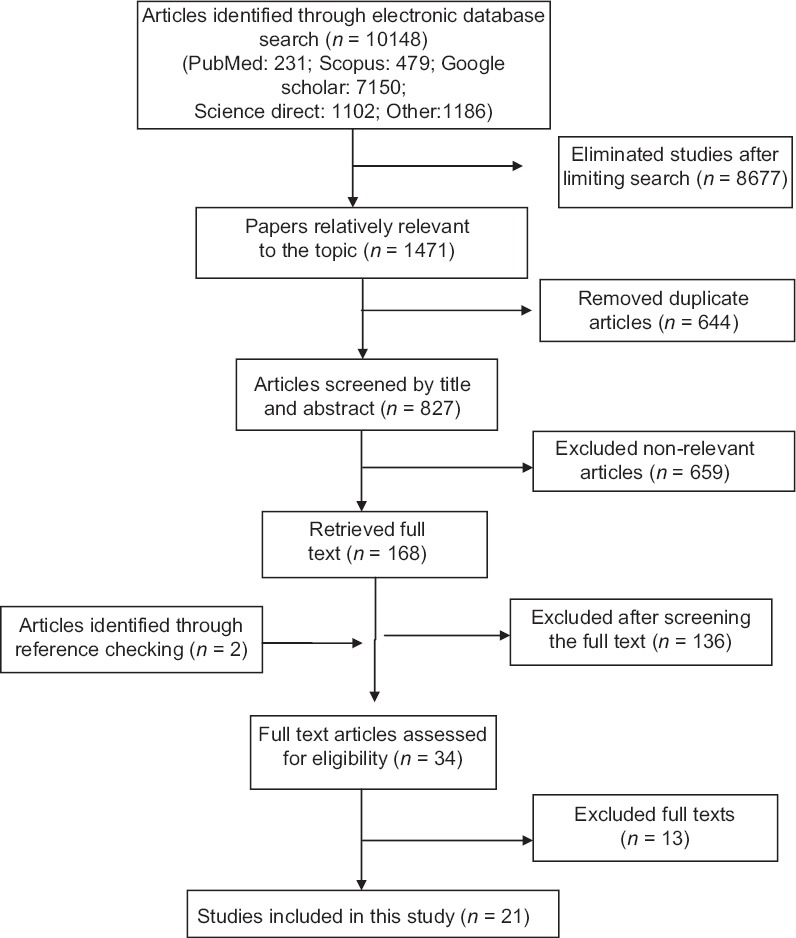

During the first part of the search in national and international databanks, 10,148 articles were found. Limiting the search strategy, 8677 were excluded. Reviewing titles and abstracts, 659 were removed in the next part of our search. During full-text review and having applied the exclusion/inclusion criteria, 13 irrelevant papers were omitted. In the final step, 21 articles including 15,680 participants were entered into the quality assessment and meta-analysis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Literature search and review flowchart for selection of primary studies

The prevalence of H. pylori infection varied between 13% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 9–17%) in Birjand[4] and 82% (95% CI: 79–85%) in Shiraz.[5] The least sample size belonged to the study carried out in Golestan[6] with 194 participants; whereas Nouraei[7] recruited 2561 individuals in the study conducted in Tehran in 2005 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies entered into the final meta-analysis

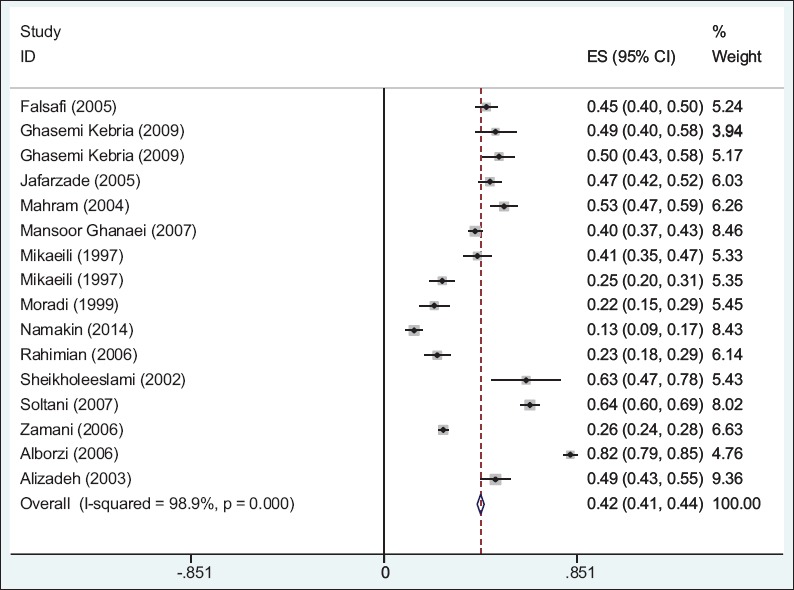

As illustrated in Figure 2, the overall H. pylori infection rate was estimated as of 54% (95% CI: 53–55%; Q = 3031, P < 0.0001). Among 15 studies used ELIZA method for H. pylori infection diagnosis, the infection rate was estimated as 60% (95% CI: 59–61%; Q = 2087, P < 0.0001). These studies reported prevalences varied between 26% (95% CI: 24–28%) in Tehran[8] and 79% (95% CI: 74–85%) in Qazvin.[9] While, studies used stool antigen test reported H. pylori prevalence rate as 44% (95% CI: 42–46%; Q = 959, P < 0.0001). The minimum and maximum prevalences among these studies were 13% (95% CI: 9–17%) in the study conducted in Birjand[4] and 82% (95% CI: 79–85%) in Alborzi study.[5]

Figure 2.

Forest plot for prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Iran

Among 11 studies investigating the association between H. pylori infection rate and age, eight papers found statistically significant associations.[6,7,9,10,11,12,13,14] Almost all of the studies compared prevalence rates of H. pylori between genders, five of which reported significant correlations.[4,8,10,15] Using P value meta-analysis method among the results of studies reported P values, the pooled P value for the association between age and H. pylori infection rate was 0.0001, whereas the pooled P value for the correlation between gender and H. pylori prevalence rate was 0.04.

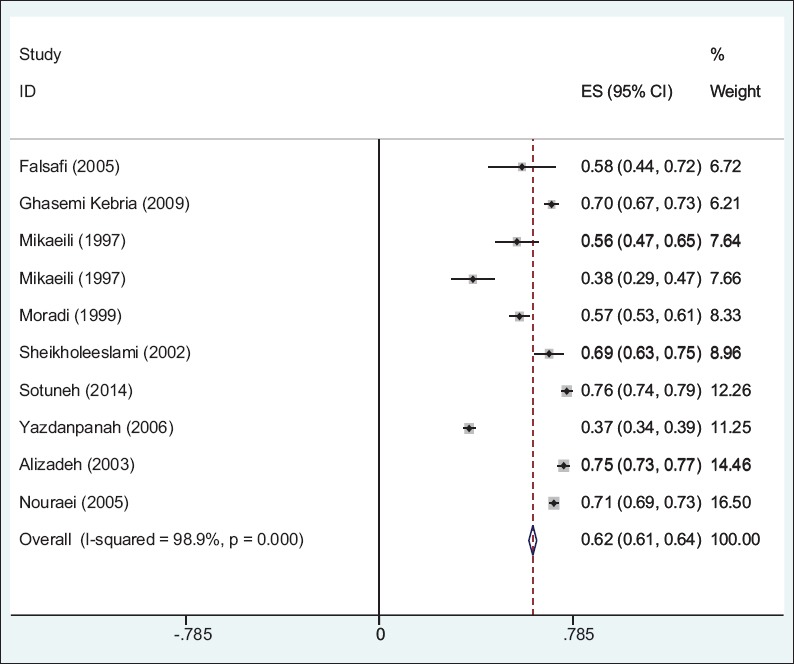

As shown in Figure 3, among 16 studies assessed the H. pylori infection rate among children (under 15), the pooled prevalence of infection was estimated as 42% (95% CI: 41–44%; Q = 1322, P < 0.0001). These prevalences were differed from 13% (95% CI: 9–17%) in Namakin study[4] in Birjand (2014) to 64% (95% CI: 60–69%) in the study conducted by Jafar et al.[16] in Sanandaj (2007). H. pylori infection rate among adults was assessed among 10 studies. Furthermore, based on Figure 4, the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection among these groups was estimated as 62% (95% CI: 61–64%; Q = 820, P < 0.0001). Kordestan[17] and Amirkola[18] had minimum and maximum prevalences (36%; 95% CI: 34%–39% and 76%; 95% CI: 74–78%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Forest plots indicating the prevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori infection among children

Figure 4.

Forest plots indicating the prevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori infection among adults

Using meta-regression models, the coefficients (P values) of the effects of study date, mean age, male percent, and diagnostic method on the heterogeneity were 0.0002 (0.9), 0.006 (0.055), 0.004 (0.6), and −0.1 (0.2), respectively. Adding these variables to the meta-regression model did not change the Tau square index.

DISCUSSION

We found in the current systematic review and meta-analysis that the prevalence of H. pylori infection among Iranian population is 54%. We also observed that this prevalence was significantly different according to age and H. pylori diagnostic method.

It should be noted that we entered studies randomly selected healthy individuals within the community. Eshraghian[1] in 2014 systematically reviewed the studies estimating the prevalence of H. pylori infection among healthy population of Eastern Mediterranean regional office countries. According to this study, the prevalence rate of H. pylori infection in eight investigated countries ranged from 22% to 87.6%. Kingdom Saudi Arabia[22,23] and Jordan[24] had similar prevalences to Iran while the infection rates in Libya, Tunisia, UAE, Egypt, and Oman were more than that reported among the Iranian population estimated in the current study.[1] Among the studies investigated the H. pylori infection rate outside the region, Japan,[25] England,[3] and Madagascar[26] had lower rates of the infection while H. pylori was more common in Taiwan[27] and China.[28] It should be noted that studies carried out in England and Madagascar and many other similar studies estimated the infection rate only among children, and such comparisons would be prone to some information biases. In addition, such differences may be due to the influence of factors such as nutritional habits and climates[4] as well as socioeconomic status and ethnic background[15] which are remarkably different in different parts of the world. Moreover, different methods of infection diagnosis applied in the above studies should be considered as a probable explanation for great variabilities in reported prevalences.

A great number of the studies entered in the current meta-analysis showed that H. pylori infection is associated with male gender. Similar findings were reported in surveys conducted among Asian South-Eastern countries.[25,28] Moreover, de Marte and Parsonnet in a meta-analysis[29] confirmed that H. pylori infection is more common in males than females only among adults. This study indicates that the mentioned predominance cannot be observed among children because different exposure to antibiotics as well as different immunity between males and females in these two age groups. It seems that the male predominance indicates more exposure of males to infection and also their long-term clinical outcomes.[15] However, such association was not observed among Taiwanese.[27] Among studies carried out in Eastern Mediterranean countries, only Al-Balushi et al.[30] and Al Faleh et al.[22] assessed the relationship between gender and H. pylori infection. The latter study conducted among 16–18 years old individuals living in KSA, introduced female gender as a risk factor for H. pylori infection.

The association between age and H. pylori infection has been proven in the studies performed in Egypt,[31] KSA,[23,32] Oman,[30] Japan,[25] China,[28] Madagascar,[26] and the USA.[33] That was in keeping with those observed in our systematic review and meta-analysis. It should be explained by the long duration of exposure to H. pylori in the higher ages compared to children. It is also important to note that all of these studies have reported the infection prevalence diagnosed by two methods (ELIZA and stool antigen). The latter method had been applied only among children. However, we should consider the probable differences in the accuracy of these two diagnostic tests and report the different results between children and adults with cautious.

Many studies investigating the H. pylori prevalence estimated prevalence only in specific populations such as patients or candidates for endoscopy. While many similar studies assessed the H. pylori infection among patients or special subgroups or at last symptomatic individuals referring to health and medical centers, such participants were not a representative sample for the whole population, and the estimates could not be exactly generalized to the reference study area.

Initial reports of H. pylori infection from Iran indicated a high prevalence of more than 85%.[34] Our study indicates that the prevalence has decreased to near 50%. This is in concordance with better sanitation and improved infrastructures in the country and subsequent decrease in infectious diseases. This may have changed the pattern of gastrointestinal diseases in Iran as one can see a decrease in distal gastric cancers and acid peptic disease. This pattern was previously reported with immunoproliferative small intestinal disease which was once the most common cause of malabsorption in at least parts of Iran but now only is reported very rarely. This disease was also linked to gastrointestinal infections.[35,36]

According to the met regression models, each year increase in the study date increased the H. pylori infection rate more than 0.002% while this prevalence increased approximately 0.04% and 0.06% per one percent increase in the distribution of male gender as well as 1-year increase in the mean age of the participants, respectively. However, none of these coefficients were statistically significant. Moreover, the between studies variance was not changed after controlling the effects of these factors indicating that none of these factors are associated with heterogeneity among the studies.

One of the most important limitations in our systematic review and meta-analysis was different methods of infection diagnosis. Because of the different sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic tests, combining the results should be performed with caution, even though this factor appeared to have negligible effect on the heterogeneity of the between-studies results. Larger multicenter studies are needed to provide exact information about H. pylori infection prevalence and its related factors within the country.

CONCLUSIONS

Our meta-analysis provided evidences that half of the Iranian population particularly adults and males are infected to H. pylori. Persistent monitoring of the situation of the infection, implementation of proper sanitary facilities, as well as improvement in the level of education, especially among adult population could be effective strategies to control this infection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eshraghian A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among the healthy population in Iran and countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17618–25. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayehmiri F, Kiani F, Sayehmiri K, Soroush S, Asadollahi K, Alikhani MY, et al. Prevalence of cagA and vacA among Helicobacter pylori-infected patients in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:686–96. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donohoe JM, Sullivan PB, Scott R, Rogers T, Brueton MJ, Barltrop D. Recurrent abdominal pain and Helicobacter pylori in a community-based sample of London children. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:961–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namakin K. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic children in Birjand, Eastern Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alborzi A, Soltani J, Pourabbas B, Oboodi B, Haghighat M, Hayati M, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children (South of Iran) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:259–61. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghasemi-Kebria F, Asmar M, Angizeh AH, Behnam-Pour N, Bazouri M, Tazike E, et al. Seroepidemiology and determination of age trend of Helicobacter pylori contamination in Golestan province in 2008. Govaresh. 2009;14:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nouraie M, Latifi-Navid S, Rezvan H, Radmard AR, Maghsudlu M, Zaer-Rezaii H, et al. Childhood hygienic practice and family education status determine the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Iran. Helicobacter. 2009;14:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamani A, Shariat M, Oloomi Yazdi Z, Bahremand S, Akbari Asbagh P, Dejakam A. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and serum ferritin level in primary school children in Tehran-Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49:314–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheykh H, Ghasemibarghi R, Moosavi H. Comparison of prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural areas of Gzvin (2002) J Gazvin Univ Med Sci. 2004;32:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babamahmoodi F, Ajami A, Kalhor M, Shafiei G, Khalilian A. Seroepidemiology if H. pylori infection in Sari Cirt of Iran in 2001. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2004;14:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falsafi T, Valizadeh N, Sepehr S, Najafi M. Application of a stool antigen test to evaluate the incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents from Tehran, Iran. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1094–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1094-1097.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halakou A, Khormali M, Yamrali A, Zandi TM. The study of seroepidemiology antibodies against Helicobacter pylori in Izeh, a city of Khozestan province in Iran. Med Lab J. 2011;5:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moradi A, Rashidy-Pour A. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Semnan. Koomesh. 2000;1:53–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alizadeh AH, Ansari S, Ranjbar M, Shalmani HM, Habibi I, Firouzi M, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Nahavand: A population-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:129–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafarzadeh A, Ahmedi-Kahanali J, Bahrami M, Taghipour Z. Seroprevalence of anti-Helicobacter pylori and anti-CagA antibodies among healthy children according to age, sex, ABO blood groups and Rh status in South-East of Iran. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2007;18:165–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jafar S, Jalil A, Soheila N, Sirous S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children, a population-based cross-sectional study in west Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:13–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazdanpanah K, Ezzatollah R. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Kordestan province in 2007. J Kordestan Univ Med Sci. 2009;14:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sotuneh N, Hosseini SR, Shokri-Shirvani J, Bijani A, Ghadimi R. Helicobacter pylori infection and metabolic parameters: Is there an association in elderly population? Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:1537–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moosazadeh M, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Emrani Z, Amiresmaili M. Prevalence of unwanted pregnancy in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29:e277–90. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haghdoost AA, Moosazadeh M. The prevalence of cigarette smoking among students of Iran's universities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:717–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45:247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Faleh FZ, Ali S, Aljebreen AM, Alhammad E, Abdo AA. Seroprevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori and viral hepatitis A among adolescents in three regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Is there any correlation? Helicobacter. 2010;15:532–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MA, Ghazi HO. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:114–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bani-Hani KE, Shatnawi NJ, El Qaderi S, Khader YS, Bani-Hani BK. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in healthy schoolchildren. Chin J Dig Dis. 2006;7:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueda J, Gosho M, Inui Y, Matsuda T, Sakakibara M, Mabe K, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth year and geographic area in Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:105–10. doi: 10.1111/hel.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravelomanana L, Imbert P, Kalach N, Ramarovavy G, Richard V, Carod JF, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in children in Madagascar: Risk factors for acquisition. Trop Gastroenterol. 2013;34:244–51. doi: 10.7869/tg.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen HL, Chen MJ, Shih SC, Wang HY, Lin IT, Bair MJ. Socioeconomic status, personal habits, and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the inhabitants of Lanyu. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Y, Zhou X, Wu J, Su J, Zhang G. Risk Factors and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in persistent high incidence area of gastric carcinoma in Yangzhong city. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/481365. 481365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Martel C, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gender: A meta-analysis of population-based prevalence surveys. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2292–301. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Balushi MS, Al-Busaidi JZ, Al-Daihani MS, Shafeeq MO, Hasson SS. Sero-prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among asymptomatic healthy Omani blood donors. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:146–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naficy AB, Frenck RW, Abu-Elyazeed R, Kim Y, Rao MR, Savarino SJ, et al. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a population of Egyptian children. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:928–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Moagel MA, Evans DG, Abdulghani ME, Adam E, Evans DJ, Jr, Malaty HM, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter (formerly Campylobacter) pylori infection in Saudia Arabia, and comparison of those with and without upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:944–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everhart JE, Kruszon-Moran D, Perez-Perez GI, Tralka TS, McQuillan G. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1359–63. doi: 10.1086/315384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malekzadeh R, Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Mikaeli J, Yazdanbod A, Merat S, et al. Prevalence of gastric precancerous lesions in Ardabil, a high incidence province for gastric adenocarcinoma in the northwest of Iran. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:37–42. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massarrat S, Saberi-Firoozi M, Soleimani A, Himmelmann GW, Hitzges M, Keshavarz H. Peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome and constipation in two populations in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lankarani KB, Masoompour SM, Masoompour MB, Malekzadeh R, Tabei SZ, Haghshenas M. Changing epidemiology of IPSID in Southern Iran. Gut. 2005;54:311–2. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.050526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]