Abstract

Background:

Many plants possess antioxidants that exhibit additive or synergistic activities.

Objective:

In this study, an ethanol-extracted flavonoid extracted from mulberry fruit (FEM) was evaluated for the antioxidant activity in vitro and the hemolysis in red blood cell (RBC) and lipid peroxidation in liver in vivo.

Materials and Methods:

Antioxidant activities in vitro were measured by quantifying its 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging activity, reducing power, and Fe2+-chelating ability. FEM inhibits hemolysis in RBCs and effects of lipid peroxidation in the liver were estimated.

Results:

The total content of flavonoid compounds was 187.23 mg of quercetin equivalents per grams dried material. In the in vitro assays, FEM demonstrated a strong antioxidant effect, especially in DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power. Mouse RBC hemolysis induced by H2O2 was significantly inhibited by FEM in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The effects of FEM on lipid peroxidation in liver, mitochondria, and microsome were investigated. The percentage of inhibition at high concentration (100 μg/mL) of FEM was 45.51%, 39.36%, and 42.78% for liver, mitochondria, and microsomes, respectively. These results suggest that the FEM possesses a strong antioxidant activity both in vivo and in vitro.

SUMMARY

The total content of flavonoid compounds in mulberry fruit was 187.23 mg/g dried material

FEM showed a strong antioxidant effect, especially in 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl scavenging activity and reducing power

Mouse red blood cell hemolysis induced by H2O2 was significantly inhibited by FEM in a dose- and time-dependent manner

The inhibition percentage at high concentration of FEM was 45.51%, 39.36%, and 42.78% for mouse’s liver, mitochondrial, and microsomes, respectively.

Abbreviations used: FEM: Flavonoid Extracted from Mulberry fruit, H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide, DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, EDTA: Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, MDA: malondialdehyde, TBA: 2-thiobarbituric acid, RBC: Red blood cells, DNJ: 1-deoxynojirimycin, LDL: low density lipoprotein, ROS: reactive oxygen species, EDTA2Na: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, flavonoid, hemolysis, lipid peroxidation, mulberry fruit

INTRODUCTION

Mulberry (Morus alba L.) is not only a plant source for feeding Bombyx mori, but also a long-used medicinal plant in Eastern Asia countries. All parts of the mulberry, including roots, bark, and leaves are reported to have antioxidants,[1,2] antidiabetic,[3] antihyperlipidemic properties.[4] It may also function to prevent from cardiovascular diseases,[5] and inhibit cancer, as well as a diuretic.[6]

Mulberry fruit is used as an herbal medicine and is widely regarded as a nutritious food in China. Mulberry fruit may protect against liver and kidney damage, strengthen the joints, improve eyesight, have anti-aging effects, and be a treatment for sore throats, fever, hypertension, and anemia.[7] The constituents of mulberry fruit include flavonoids, polyphenols, anthocyanins, polysaccharides, fatty acids, vitamins, and trace elements.[7,8,9] Numerous studies have demonstrated that mulberry fruits and leaves exhibited significant scavenging effects of free radicals and protected low-density lipoprotein (LDL) against oxidative damage. Fresh fruit extracts are excellent sources of polyphenolic compounds that exhibit antioxidant activity.[10] These medicinal capabilities are attributable to the presence of active ingredients with notable therapeutic functions.[11] Anthocyanins and water extracts from mulberry fruit can scavenge free radicals, inhibit LDL oxidation, and have beneficial effects on blood lipid levels and atherosclerosis.[6,12,13]

Antioxidants are molecules that can neutralize free radicals by accepting or donating electrons to eliminate the unpaired form of the radical, breaking the chain of oxidation reactions.[14] Many studies have shown that natural antioxidants not only play a major role against reactive oxygen species (ROS), but also trigger lipid peroxidation.[15,16,17] Oxidative damage caused by ROS, such as the superoxide and hydroxyl radicals to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids may trigger various diseases, including cardiovascular disease. Epidemiological studies have shown that the administration of antioxidants may decrease the probability of cardiovascular diseases.[18]

However, few studies have evaluated the ethanol flavonoid extract from mulberry fruit (FEM) and its effect on in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity. In the present study, our goal was to extract flavonoids from mulberry fruit using ethanol and to evaluate the antioxidant activity in vitro and the hemolysis in red blood cell (RBC) and lipid peroxidation in liver in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Mulberry fruit was harvested from the plantation of the National Mulberry Orchard (Zhenjiang, PR China). Mice of clean grade were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Jiangsu University (Zhenjiang, China). 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ferrozine, potassium ferricyanide, ferrous chloride (FeCl2), and ferric chloride were purchased from Bio Basic Inc., (Toronto, Canada). Other reagents were obtained from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., (Beijing, China). All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade.

Extraction of flavonoid from mulberry fruit

The fresh mulberry fruit (500 g) was milled using a blender and extracted with 1000 mL of ethanol (70%) at 80°C for 2 h using a Soxhlet apparatus. The extract was filtered and extracted again under the same conditions with fresh solvent. The extract was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min. The supernatant (which constitutes the FEM) was concentrated to 100 mL under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator.

Estimation of total flavonoid content

Total flavonoid content was determined using the aluminum chloride method.[19] From the extractions, different concentrations of the quercetin standard solution were diluted appropriately and mixed with 0.3 mL 10% NaNO2. After standing for 5 min at room temperature, 0.3 mL of 10% AlCl3 and 2 mL of 1 M NaOH were added. The mixture was allowed to rest for 15 min at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm, with distilled water used as a blank control. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

Flavonoid content was calculated as the quercetin concentration (mg/g) using the following equation based on the calibration curve.

Y = 0.0056x − 0.0013, R2 = 0.998

Where, Y is the absorbance and x is the quercetin equivalent (µg/g).

Antioxidant activity assay in vitro

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical-scavenging activity

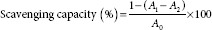

The DPPH radical scavenging capacity was determined according to the method used by Wu et al.[20] A sample of the different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/mL) was mixed with 2 mL of 0.04 mg/mL DPPH in ethanol. The mixture was shaken vigorously and allowed to stand at 25°C for 30 min. Then, it was centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min, after which, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a control. The DPPH radical scavenging capacity was calculated using the following formula:

where A0 is the absorbance of the control (without extract), A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the extract, and A2 is the absorbance without DPPH.

Ferrous ion chelating capacity

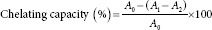

The ferrous ion chelating capacity was determined following the method of Wu et al.[20] The reaction mixture, containing 3 mL of sample at different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/mL), 0.05 ml of 2 mmol/L FeCl2 solution, and 0.2 mL of 5 mmol/L ferrozine solution, was shaken vigorously and incubated at 25°C for 10 min. The absorbance of the mixture was then measured at 562 nm. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-2Na) was used as a positive control. The ferrous ion chelating capacity of the sample was calculated as follows:

where A0 is the absorbance of the control (without extract), A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the extract, and A2 is the absorbance without EDTA.

Reducing power

Reducing power was determined based on the method of Wu et al.[20] Briefly, 1 mL of the sample at different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/mL) in phosphate buffer (0.2 mol/L, pH 6.6) was mixed with 2 mL potassium ferricyanide (1%) and incubated at 50°C for 20 min. Next, 2 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to the mixture to stop the reaction. After centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min, 2.5 mL of supernatant was mixed with 2.5 mL distilled water and 0.5 mL 0.1% ferric chloride. The mixture was allowed to rest for 10 min and absorbance was measured at 700 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a control.

Antioxidant activity assay in vivo

Red blood cell preparation

RBCs were collected in heparinized tubes from the eyes of mice via the cardiopuncture method of Žabar et al.[21] Whole blood was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma and buffy coat layers were discarded, and an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: pH 7.4) was added. This procedure was repeated 3 times and the erythrocytes were diluted with PBS to obtain a 4% suspension.

Erythrocyte hemolysis

Erythrocytes were hemolyzed using H2O2 and the modified method of Lalitha and Selvam.[22] One milliliter of erythrocyte suspension (4%) was mixed with 1 mL of FEM at the concentrations (10, 30, 55, 80, and 100 µg/mL) and then added 1 mL of H2O2 (100 mmol/L in PBS). The blank control consisted of 2 mL of PBS and 1 mL RBC suspension and the induced control consisted of 1 mL of PBS, 1 mL RBC suspension, and 1 mL of H2O2. The mixture was incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, 120 min, and 150 min, and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The RBC-free supernatant solution from each tube was transferred to cuvettes. Absorbance was measured at 415 nm in a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-VIS 1650, Tokyo, Japan). Each sample was measured in triplicate. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated using the equation:

Hemolysis percentage (%) = [Ab(sample)/Ab(induced control)] × 100%

Percent of hemolysis inhibition

= [(Ab(induced control) − Ab(sample))/Ab(induced control) − Ab(blank control)] ×100%

Preparation of mitochondrial and microsomal suspension

Mice livers were collected and homogenized in buffer (25 mmol sucrose, 0.5% protease inhibitor cocktail, and 10 mmol HEPES, pH 7.4) using a hand homogenizer. The crude mitochondria were prepared by differential centrifugation at 1000 g for 30 min and at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The mitochondrial suspension was obtained from the precipitate using a 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer solution. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The extracted microsome was collected from the precipitate and dissolved in a 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer solution for future use.[23]

Determination of mitochondria swelling

The swelling of liver mitochondria was achieved using the method of Dutra and Bechara.[24] Briefly, 1 mL of liver mitochondrial suspension (1%) was mixed with different concentrations of FEM (10, 30, 55, 80, and 100 µg/mL) and 2 mL of the inducer was added (5 µmol/L FeSO4 and 0.1 mmol/L ascorbic acid) to stimulate mitochondrial swelling. The mixture was incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min, and centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Absorbance was measured at 520 nm.

Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by thiobarbituric acid reactive substance method

Lipid peroxidation was determined using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactive substance method.[25] 1 mL of liver mitochondria suspension (1%) was thoroughly mixed with the different concentrations of FEM (10, 30, 55, 80, and 100 µg/mL). Then, 100 μL of 15 mM FeSO4 and 50 μL of 0.1 mmol/L ascorbic acid were added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Next, 1 mL of 15% TCA and 1 mL of 0.67% TBA were added to stop the reaction. The mixture was incubated in boiling water for 15 min. After it had cooled down, the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm.

Inhibition ratio

= [(Ab(induced control) − Ab(sample))/Ab(induced control) − Ab(blank control)] ×100%.

Statistical analysis

All tests were carried out in triplicate for the three separate experiments. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way analysis of variance. Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Extract yield and total flavonoids content in mulberry fruit

The dried FEM was obtained by freeze-drying (EYELA FDU-2100, Japan) the extract after concentrating in a rotary evaporator. The yield of ethanol extract was 53 mg/g from fresh mulberry fruit. Flavonoids content was 20.4 mg/g in fresh mulberry fruit and 187.23 mg/g in dried fruit.

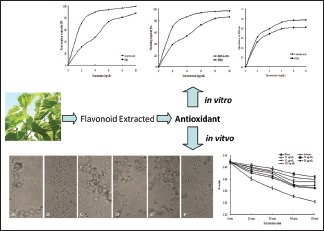

Antioxidant activity in vitro

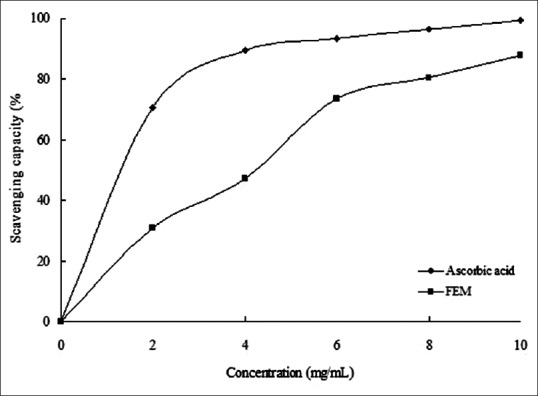

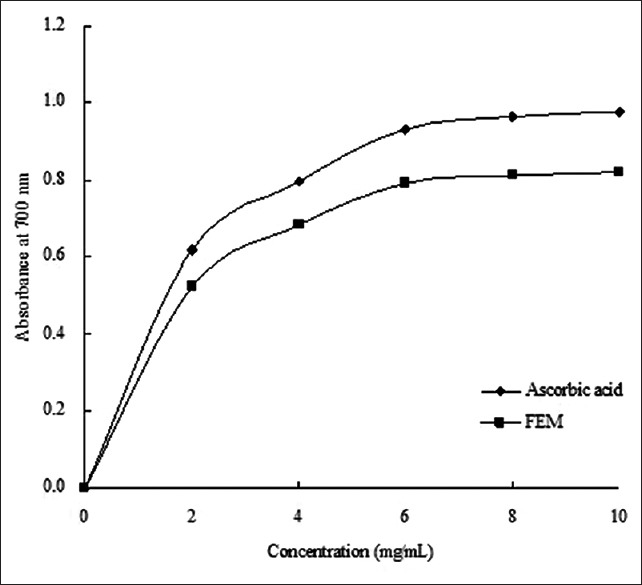

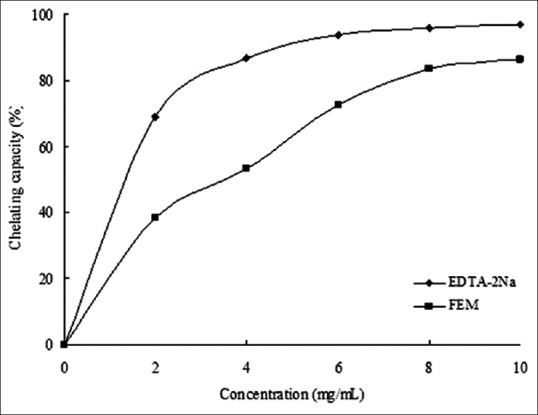

The antioxidant properties in vitro were largely DPPH radical scavenging, ferrous ion chelating capacity, and reducing power. The ethanol extract of mulberry fruit exhibited all these properties in a concentration-dependent manner [Figures 1–3]. The decrease in absorbance of the DPPH radical was caused by antioxidant scavenging of the radical and donating hydrogen. Ascorbic acid exhibited an excellent scavenging activity (IC50 = 0.186 mg/mL). FEM also showed strong scavenging activity with an IC50 value of 0.518 mg/mL [Figure 1]. Similarly, EDTA-2Na exhibited strong Fe2+-chelating activity, and even at the lowest concentration of 2 mg/mL, the chelating rate was 69.12%. However, while FEM showed little Fe2+-chelating activity at low concentrations, activity increased rapidly with increasing concentration. At 6 mg/mL, FEM reached a level of 72.6% [Figure 2]. As shown in Figure 3, the reducing power of FEM was 0.522 at 2.0 mg/mL and 0.685 at 4.0 mg/mL. Ascorbic acid exhibited only slightly higher activity, with a reducing power of 0.617 and 0.794 at 2.0 mg/mL and 4.0 mg/mL, respectively.

Figure 1.

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging capacity of FEM. The absorbance values were converted to scavenging capacity (%) and data were plotted as the mean of replicate scavenging capacity (%) ± standard deviation (n = 3) against extract concentration in mg extract per ml reaction volume. Linear regression analysis was used to calculate IC50 value

Figure 3.

Reducing power of FEM. The absorbance values were converted directly plotted as the mean of replicate absorbance values ± standard deviation (n = 3) against extract concentration in mg extract per ml reaction volume

Figure 2.

Fe2+-chelating activities of FEM. The absorbance values were converted to chelating effects (%) and data were plotted as the mean of replicate chelating effects (%) ± standard deviation (n = 3) against extract concentration in mg extract per ml reaction volume

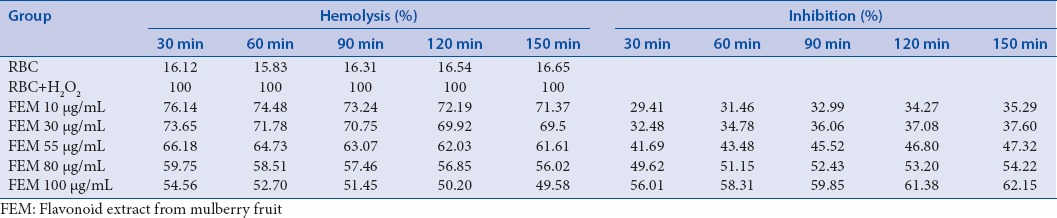

Red blood cell hemolysis by H2O2-induced oxidant stress

To determine the effects of FEM on hemolysis of RBCs, both hemolytic and antihemolytic (i.e., hemolytic inhibition) tests were conducted. The ethanol extract of mulberry fruit exhibited both hemolytic and antihemolytic properties in a dose- and time-dependent manner [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of flavonoid extract from mulberry fruit on hemolysis and inhibition of red blood cells from mice induced by H2O2

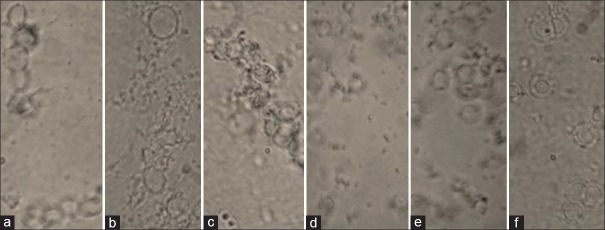

In both experiments, the lowest dose of FEM exhibited slightly beneficial effects on RBC membranes. The percentage of hemolysis was the highest for 10 µg/mL and it gradually declined, as incubation time was increased from 30 min to 150 min. In addition to the incubation time, higher concentrations resulted in a decline in RBC hemolysis. Hemolysis was the lowest for the 100 µg/mL concentration with incubation time of 150 min. Conversely, the percentage of hemolytic inhibition increased with increasing concentration and incubation time [Table 1]. The morphology of RBCs treated with FEM during H2O2-induced oxidant stress is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Morphology of red blood cells during H2O2-induced oxidant stress. (a) normal control; (b) H2O2-induced control; (c) FEM 10 µg/mL; (d) FEM 55 µg/mL; (e) FEM 80 µg/mL; (f) FEM 100 µg/mL

Lipid peroxidation of mice liver

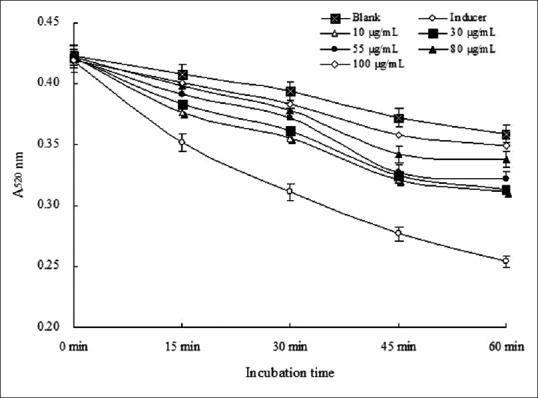

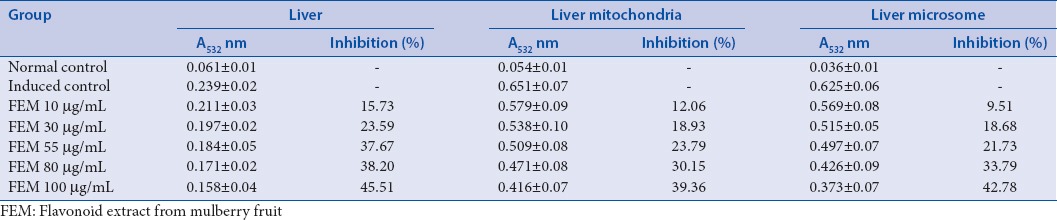

Lipid peroxidation of mice liver induced by FeSO4-ascorbic acid created membrane damage. Figure 5 shows that the absorbance at 520 nm decreased with the incubation time in all groups; however, it decreased rapidly in the induced group. These results show that mitochondrial swelling is increasing. They also indicate that FEM retards liver mitochondrial swelling in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of FEM on lipid peroxidation in the mitochondria and microsome from liver cells is shown in Table 2. The absorbance at 520 nm corresponded to the amount of malondialdehyde (MDA). The content of MDA was high in all treatment groups. FEM decreased the amount of MDA in a dose-dependent manner. The percentage of inhibition at the highest concentration (100 µg/mL) of FEM was 45.51%, 39.36%, and 42.78% for liver, mitochondria, and microsomes, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of FEM on mitochondrial swelling in mice liver

Table 2.

Effect of flavonoid extract from mulberry fruit on malondialdehyde of mitochondria and microsome from mice liver

DISCUSSION

Flavonoids are major secondary metabolites and play an important role in mulberry plants. Flavonoids were detected in all investigated parts of the plant. Overall, the flavonoid content was 28.7 mg/g in mulberry leaves,[4] 88 mg/g in mulberry twigs, and 141 mg/g in mulberry root bark.[2] The present study showed that the flavonoid content in mulberry fruit was 187.23 mg/g in dried material. Mulberry fruit contained the highest levels of flavonoid in all the parts of the plant, and flavonoid content was much higher than in Choerospondias axillaris fruit (36.5 mg/g).[26]

The role of an antioxidant is to remove free radicals.In vitro antioxidant activities of DPPH radicals, Fe2+-chelating capacity, and reducing power were used to test the antioxidant power of mulberry extract. The DPPH assay is a popular radical scavenging test for natural products.[20] The decrease in absorbance of the DPPH radical due to the antioxidant was caused by scavenging of the radical by hydrogen-donating entities.[27] Ferrous ions (Fe2+) can catalyze and induce superoxide anions to form the more harmful hydroxyl radicals.[28] Reducing power is widely used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of plant extracts. Bae and Suh reported that an ethanol extract of mulberry fruit effectively scavenged free radicals, including the DPPH radical, hydroxyl and superoxide anions, and exhibited a moderate ability to inhibit linoleic acid oxidation induced by hemoglobin in vitro.[29]

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis illustrated that the main flavonols in mulberry fruit were rutin, morin, quercetin, and myricetin. These four flavonols are reported to be effective antioxidants.[17,29,30] In this study, FEM exhibited DPPH radical scavenging activity in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 0.518 mg/mL [Figure 1], Fe2+-chelating activity reached a level of 72.6% at high concentrations (6 mg/mL) [Figure 2], and the reducing power of FEM showed similar activity to ascorbic acid [Figure 3]. Chang et al. reported that flavonols from mulberry twigs and root bark have shown significant antioxidant effects, including superoxide inhibition and reducing activity.[2] The antioxidant mechanism of flavonols is reflected in its scavenging potential and metal chelating ability, and these factors are dependent upon their structure and the number and position of the hydroxyl groups.[31]

The RBC membrane is well adapted to the formation of OH− and O2 from H2O2. Oxidant damage of the cell membrane, induced by H2O2 can result in increased erythrocyte hemolysis and inhibition rate.[21] Our result indicated that RBC hemolysis was inhibited by FEM with varying degrees of inhibition. An increase in the concentration of FEM at the outer membrane leads to diffuse to the internal membrane until it gets to the specific concentration that promotes membrane disruption and induces hemolysis.[32] The flavonoid extract from mulberry fruit can accept electrons and scavenge OH that was induced by H2O2. Certain flavonoids may interact with the membrane, leading to a decrease in its fluidity and the diffusion of free radicals into the RBC.[33]

Lipid peroxidation is a complex process involving the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids that are responsible for long-term damage to cells.[2,34] Chen et al. obtained similar results and found that hypobaric storage could reduce MDA accumulation of ROS.[35] MDA, a lipid peroxidation product, is an indicator of ROS generation in the tissue.[36] The inhibition of lipid peroxidation is of great importance in disease processes that involves free radicals.[37] The inhibition of lipid peroxide formation by FEM showed the maximum inhibition of peroxide formation with a high concentration for liver, mitochondria, and microsome. The levels of MDA were significantly higher in the liver of FeSO4-Vc-induced mice than in those of normal mice [Table 2]. Similar findings have been reported in tissues of D-gal-treated mice.[38,39] The effect of flavonoids from mulberry fruit accelerates the repair of mitochondrial membrane injury induced by Fe2+-Vc.[40]

Yang et al. showed that a freeze-dried powder of Forsythia suspense Leaves inhibited the formation of a lipid peroxidation product, increased antioxidant enzyme activity, and repressed the development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic rats.[31] In general, mulberry fruit is a natural and healthy food with hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects, and these beneficial effects may be attributed to phytochemical constituents. It contains flavonoids, anthocyanins, phenolics, fiber, fatty acids, vitamins, and trace elements.

CONCLUSION

The flavonoid ethanol extracted from mulberry fruit (FEM) was 53 mg/g from fresh mulberry fruit. FEM exhibited a strong antioxidant effect, especially in DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power. RBC hemolysis induced by H2O2 was significantly inhibited by FEM in a dose- and time-dependent manner. FEM exhibited the lipid peroxidation in liver, mitochondria, and microsomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Zhongzheng Gui

Zhongzheng Gui, is a Professor at Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, China. He is the chief of Functional Bioactive Products Laboratory since 2003. His experience in the area of Functional Natural Products, working mainly in: Silkworm, mulberry, and their biomedical applications. His research program covers various subject areas, including insect biochemistry and molecular biology, microbiology and biotransformation, and biomedical.

Acknowledgment

The Special Fund funded this work for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (No. 201403064), and Independent Innovation of Agricultural Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province (No. CX (13) 3085), P.R. China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doi K, Kojima T, Fujimoto Y. Mulberry leaf extract inhibits the oxidative modification of rabbit and human low density lipoprotein. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:1066–71. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang LW, Juang LJ, Wang BS, Wang MY, Tai HM, Hung WJ, et al. Antioxidant and antityrosinase activity of mulberry (Morus alba L.) twigs and root bark. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:785–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma SB, Gupta S, Ac R, Singh UR, Rajpoot R, Shukla SK. Antidiabetogenic action of Morus rubra L.leaf extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;62:247–55. doi: 10.1211.jpp/62.02.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Li X. Hypolipidemic effect of flavonoids from mulberry leaves in triton WR-1339 induced hyperlipidemic mice. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16 Suppl 1:290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan KC, Ho HH, Huang CN, Lin MC, Chen HM, Wang CJ. Mulberry leaf extract inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration involving a block of small GTPase and Akt/NF-kappaB signals. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:9147–53. doi: 10.1021/jf902507k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang CY, Liu Y, Jia J, Sivakumar TR, Fan T, Gui ZZ. Optimization of fermentation process for preparation of mulberry fruit wine by response surface methodology. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:227–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Yang L, Zheng H. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruit in hyperlipidaemia rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobus-Cisowska J, Gramza-Michalowska A, Kmiecik D, Flaczyk E, Korczak J. Mulberry fruit as an antioxidant component in muesli. Agric Sci. 2013;4:130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivakumar TR, Ajaykrishna PG, Fang Y, Ren ZX, Chen C, Jin C, et al. Comparative analysis of the chemical composition of different mulberry fruit varieties. Sericologia. 2015;55:221–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgen M, Serce S, Kaya C. Phytochemical and antioxidant properties of anthocyanin-rich Morus nigra and Morus rubra fruits. SCI Hortic Amsterdam. 2009;119:275–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez-Salcedo EM, Sendra E, Carbonell-Barrachina ÁA, Martínez JJ, Hernández F. Fatty acids composition of Spanish black (Morus nigra L.) and white (Morus alba L) mulberries. Food Chem. 2016;190:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du Q, Zheng J, Xu Y. Composition of anthocyanins in mulberry and their antioxidant activity. J Food Compos Anal. 2008;21:390–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan KC, Yang MY, Lin MC, Lee YJ, Chang WC, Wang CJ. Mulberry leaf extract inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits and in cultured aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:2780–8. doi: 10.1021/jf305328d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abirami A, Nagarani G, Siddhuraju P. In vitro antioxidant, anti-diabetic, cholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of fresh juice from Citrus hystrix and C.maxima fruits. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2014;3:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang CC, Huang HP, Lee YJ, Tang YH, Wang CJ. Hepatoprotective effect of mulberry water extracts on ethanol-induced liver injury via anti-inflammation and inhibition of lipogenesis in C57BL/6J mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;62:786–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saravanan S, Parimelazhagan T. In vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-diabetic properties of polyphenols of Passiflora ligularis Juss. fruit pulp. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2014;3:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu P, Ma G, Li N, Deng Q, Yin Y, Huang R. Investigation of in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of flavonoids rich extract from the berries of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Ait.) Hassk. Food Chem. 2015;173:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abe J, Berk BC. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of signal transduction in cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1998;8:59–64. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JY, Tang CY. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents in selected fruits and vegetables, as well as their stimulatory effects on mouse splenocyte proliferation. Food Chem. 2007;101:140–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu F, Yan H, Ma X, Jia J, Zhang G, Guo X, et al. Comparison of the structural characterization and biological activity of acidic polysaccharides from Cordyceps militaris cultured with different media. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28:2029–38. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Žabar A, Cvetković V, Rajković J, Jović J, Vasiljević P, Mitrović T. Larvicidal activity and in vitro effects of green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) water infusion. Biol Nyssana. 2013;4:75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalitha S, Selvam R. Prevention of H2O2-induced red blood cell lipid peroxidation and hemolysis by aqueous extracted turmeric. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 1999;8:113–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.1999.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun HD, Ru YW, Zhang DJ, Yin SY, Yin L, Xie YY, et al. Proteomic analysis of glutathione S-transferase isoforms in mouse liver mitochondria. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3435–42. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i26.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutra F, Bechara EJ. Aminoacetone induces iron-mediated oxidative damage to isolated rat liver mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430:284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakat S, Juvekar AR, Gambhire MN. In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of methanol extract of Oxalis corniculata Linn. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;2:146–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Gao XD, Zhou GC, Cai L, Yao WB. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of aqueous extract from Choerospondias axillaris fruit. Food Chem. 2008;106:888–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashwini M, Balaganesh J, Balamurugan S, Murugan SB, Sathishkumar R. Antioxidant activity in in vivo and in vivo cultures of onion varieties (Bellary and CO 3) J Mod Biotechnol. 2013;2:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lan MB, Guo J, Zhao HL, Yuan HH. Antioxidant and anti-tumor activities of purified polysaccharides with low molecular weights from Magnolia officinalis. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6:1025–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Wang L, Wei H, Yang ZQ, Wang W. Structure-activity relationship of flavonoids in antioxidant activity. Food Sci. 2006;27:233–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae S, Suh HJ. Antioxidant activities of five different mulberry cultivars in Korea. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2007;40:955–62. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang JX, Yang C, Qiu J, Huang C. In vitro Antioxidant properties of Forsythia suspense leaves flavonoids. Nat Prod Res. 2007;19:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pazos M, Gallardo JM, Torres JL, Medina I. Activity of grape polyphenols as inhibitors of the oxidation of fish lipids and fish muscle. Food Chem. 2005;92:547–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleszczynska H, Bonarska D, Luczynski J, Witek S, Sarapuk J. Hemolysis of erythrocytes and erythrocyte membrane fluidity changes by new lysosomotropic compounds. J Fluoresc. 2005;15:137–41. doi: 10.1007/s10895-005-2521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa RM, Magalhães AS, Pereira JA, Andrade PB, Valentão P, Carvalho M, et al. Evaluation of free radical-scavenging and antihemolytic activities of quince (Cydonia oblonga) leaf: A comparative study with green tea (Camellia sinensis) Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:860–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H, Yang H, Gao H, Long J, Tao F, Fang X, et al. Effect of hypobaric storage on quality, antioxidant enzyme and antioxidant capability of the Chinese bayberry fruits. Chem Central J. 2013;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-7-4. doi:10.1186/1752-153X-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Souleymane M, Konan G, Houphouet FY, Souleymane M, Adou FY, Allico JD, et al. Antioxidant in vivo, in vitro activity assessment and acute toxicity of aqueous extract of gomphrena celosioides (Amaranthaceae) Experiment. 2014;23:1601–10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holley AE, Cheeseman KH. Measuring free radical reactions in vivo. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:494–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abuja PM, Albertini R. Methods for monitoring oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and oxidation resistance of lipoproteins. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;306:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu A, Ma Y, Zhu Z. Protective effect of selenoarginine against oxidative stress in D-galactose-induced aging mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:1461–4. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu SY, Dong Y, Tu J, Zhou Y, Zhou XH, Xu B. Silybum marianum oil attenuates oxidative stress and ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction in mice treated with D-galactose. Pharmacogn Mag. 2014;10(Suppl 1):S92–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.127353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]