Abstract

TLRs are thought to play a critical role in self/non-self discrimination by sensing microbial infections and initiating both innate and adaptive immunity. In this study, we demonstrate that in the absence of TLR11, a major TLR involved in recognition of Toxoplasma gondii, infection with this protozoan parasite induces an abnormal immunopathological response consisting of pancreatic tissue destruction, fat necrosis, and systemic elevations in inflammatory reactants. We further show that this immunopathology is the result of non-TLR dependent activation of IFN-γ secretion by NK cells in response to the infection. These findings reveal that in addition to triggering host resistance to infection, TLR recognition can be critical for the prevention of pathogen-induced immune destruction of self tissue.

In mediating host resistance to pathogens, the immune system relies on efficient discrimination between microbial and self molecules (1). The mammalian TLR family plays a fundamental role in this process and is able to respond to wide variety of viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic invaders (2–4). TLRs function via recognition of microbe-associated molecular patterns and TLR signaling is of critical importance in the initiation of both innate and Th1-dependent adaptive immunity (5). The function of TLRs in host defense is evidenced by the increased susceptibility to infection of mice with targeted deletions of TLRs or adaptor proteins such as MyD88 or TRIF required for signal transduction by these receptors (3). Such studies in multiple host-pathogen models have generally supported the assumption that host resistance to infection is equivalent to efficient self/non-self discrimination.

During the induction of immune responses against pathogens, it is also essential to avoid dysregulated triggering of signaling pathways that could lead to bystander pathology directed against self tissues. Although TLR signals themselves can limit self-specific immunity by regulation of Ag presentation by dendritic cells (DC)3 (6), TLR activation has been shown in certain circumstances to have pathological consequences. Examples are the TLR4-dependent shock initiated by bacterial LPS (7), the requirement for TLR3 in the entry of West Nile virus into brain tissues leading to lethal encephalitis (8), and the dependence on TLR recognition of intestinal bacteria in certain forms of colitis (9). Such observations indicate that TLR recognition can have deleterious as well as beneficial consequences for the host and thus call into question the primary role proposed for the TLR system in host defense mediated through self/non-self discrimination.

Murine infection with the intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii provides an excellent model for studying the effects of the absence of normal TLR recognition on infection induced host responses since a major TLR-TLR ligand interaction has been identified that governs innate immunity to this pathogen (10). Thus, induction of the cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ is essential for early control of T. gondii infection and production of these mediators depends on triggering of MyD88 signaling in DC early in infection (10–12). In previous studies we have demonstrated that the critical parasite ligand involved is the actin-binding protein profilin and that its agonist activity is due to interaction with TLR11 on DC. When challenged systemically with avirulent T. gondii, TLR11-deficient mice developed dramatically reduced serum IL-12 levels and partially impaired host resistance as evidenced by increased parasite load during the chronic phase of infection (10). To provide a more detailed analysis of the effects of TLR11 deficiency on the outcome of T. gondii infection, we systematically examined cellular responses of TLR11−/− mice at early time points after i.p. parasite inoculation. Unexpectedly, we found that in the absence of TLR11, mice developed a marked immunopathological response associated with NK cell IFN-γ secretion.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from Taconic Farms. Breeding stocks of TLR11−/− mice were provided by Drs. S. Ghosh and D. Zhang (Yale University, New Haven, CT), and MyD88−/− mice by Dr. S Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). Caspase1−/− mice were obtained from Dr. R. Flavell (Yale University). TLR11−/− × Caspase 1−/− mice were generated by crossing these strains. When not on a B6 background, all animals were backcrossed (N8 for TLR11−/−, N12 for MyD88−/− animals). All mice were maintained in accordance with the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines. To generate bone marrow chimeric animals, mice were exposed to 950 rad in a GammaCell 40 cesium irradiator and reconstituted on the same day with 1 × 106 bone marrow cells from the donor mouse strains. The animals were then maintained on acidified water for 4–6 wk before infection.

Toxoplasma gondii infections and histopathology

All mice were infected i.p. with an average of 20 cysts of T. gondii (ME49 strain) or 103–105 of yellow fluorescent protein-expressing T. gondii (RH strain). At day 5 postinfection, animals were necropsied, bled, and pancreatic tissues, lung, kidney and muscles were fixed in Bouin's fixative, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with H&E.

Serum biochemistry

Serum samples were tested for concentrations of amylase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and uric acid according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). The statistical significance of difference in serum enzyme levels between experimental and control animal groups was evaluated by Student's t test using Prism software.

In vivo Ab treatment

To analyze the effect of in vivo neutralization of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF, WT and TLR11−/− mice were injected i.p. with 1 mg of XMG-6 (anti-IFN-γ), 1 mg of C17.8 (anti-IL-12), or control GL113 (anti-β-galactosidase) in 0.5 ml of PBS on days 0 and day 3 postinfection. For depletion of CD4+ or CD8+T cells in vivo, mice were injected i.p. with 1 mg of anti-CD4 mAb (GK1.5) or mAb 2.43, respectively. To deplete NK cells, animals were treated with 100 μg of rabbit anti-ASGM1 (WAKO) or 1 mg of anti-NK1.1 (RP136). Depletion of CD4, CD8, and NK cells was analyzed by flow-cytometry on days 3 and 5 posttreatment and in all experiments was ≥95%.

Results

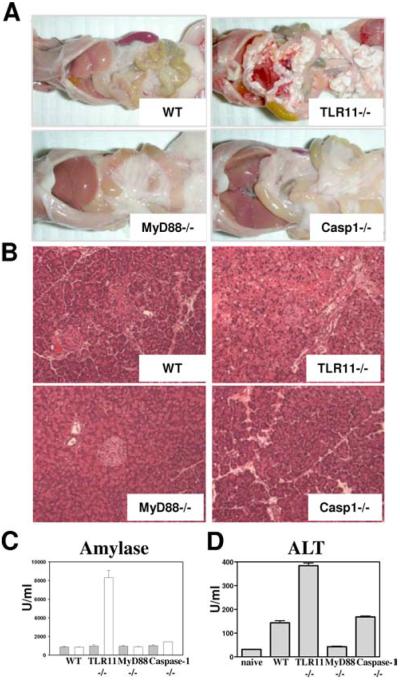

TLR11-deficient mice develop fat necrosis and acute pancreatitis in response to T. gondii infection

When examined at 5 days postinfection, TLR11−/− mice exhibited severe and widespread fat necrosis in the peritoneal serosa (Fig. 1A). In contrast, similarly infected WT mice, while producing high levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ (10), were found to be free of these pathological changes. Fat necrosis was also absent at this time point in mice lacking the Myd88 or Caspase-1 genes suggesting that the observed pathology is specifically linked to TLR11 recognition (Fig. 1A). Fat necrosis is often the result of acute pancreatitis (13). Indeed, histological analysis revealed severe destruction of acinar cells in pancreatic tissue in the T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− animals, but not in their WT (or in MyD88−/− or Caspase1−/−) counterparts (Fig. 1B). Moreover infected TLR11−/− animals displayed dramatically elevated serum levels of amylase (Fig. 1C), a hallmark of pancreatitis (13). The severity of the acute pancreatic pathology was confirmed by measurement of the inflammation and tissue-breakdown markers ALT, AST, and lactate dehydrogenase (Fig. 1D and data not shown). Thus, TLR11−/− mice infected with T. gondii develop pancreatitis, a pathologic response previously documented to occur sporadically in cats and humans with toxoplasmosis (15, 16) but, to the best of our knowledge, never reported in infected mice. In this regard, it is of interest that both felines and primates in contrast to mice lack functional TLR11 (2, 17).

FIGURE 1.

TLR11-deficient mice develop acute pancreatitis in response to T. gondii infection. A, Development of fat necrosis in T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice. WT, TLR11−/−, MyD88−/−, or Caspase1−/− were infected with an average of 20 cysts per mouse of the ME49 strain of T. gondii and the peritoneal cavities were examined 5 days later. B, Animals were infected as described above and pancreatic tissues were removed for histological analysis (H&E staining). The images shown are representative of multiple sections examined in three or four mice per group. C, WT, TLR11−/−, MyD88−/−, or Caspase1−/− were infected as described above and 5 days later serum levels of amylase were analyzed; □, T. gondii infected;  , naive controls. The data are representative of eight experiments performed. D, Serum levels of inflammation marker alanine amino-transferase (ALT) in mice infected with T. gondii. The data are representative of three experiments performed.

, naive controls. The data are representative of eight experiments performed. D, Serum levels of inflammation marker alanine amino-transferase (ALT) in mice infected with T. gondii. The data are representative of three experiments performed.

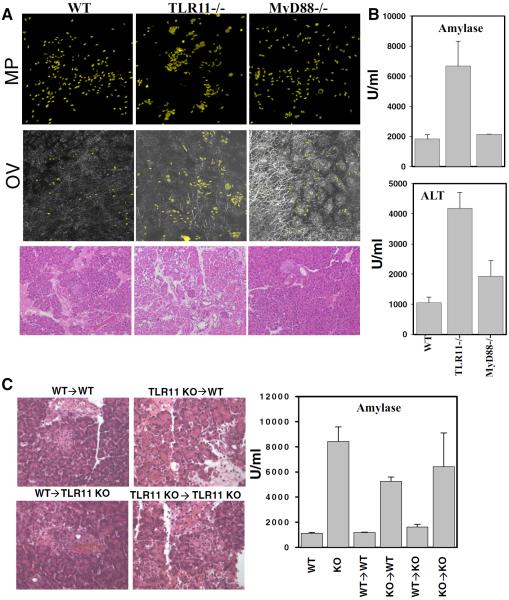

The immunopathology observed in T. gondii infected TLR11−/− mice cannot be explained by increased infection of the pancreas

One possible explanation of the observed pathology is that T. gondii targets the pancreas and that growth of the parasite and subsequent tissue destruction is enhanced in TLR11-deficient animals. Nevertheless, parasites were rarely seen in pancreatic sections from either WT, MyD88−/−, or TLR11−/− infected mice, and even when exposed to large numbers of yellow fluorescent protein-labeled tachyzoites of the highly virulent RH toxoplasma strain, no increased pathogen growth was evident at day 5 in the diseased pancreatic tissue from the latter animals (Fig. 2, A and B). Although an altered distribution of parasites was evident in the TLR11−/− tissue, this was attributable to the disrupted architecture of the pancreas resulting from the severe tissue destruction present in these animals (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Lack of TLR11 activation in the hemopoetic compartment, but not localization of T. gondii in pancreatic tissue, results in acute pancreatitis in T. gondii-infected mice. A, WT, TLR11−/−, or MyD88−/− mice were infected with 103 T. gondii tachyzoites (RH strain) expressing yellow fluorescent protein and pancreatic tissues were removed for microscopic analysis on day 5 postinfection. B, Serum levels of amylase and ALT on day 5 postinfection. The data shown are the mean ± SD, and the results are representative of four experiments performed, each involving three animals per group. C, Bone marrow chimeric animals were infected with an average of 20 cysts per mouse of the ME49 strain of T. gondii, and 5 days later, pancreatic tissues were removed for histological analysis (H&E staining) and serum levels of amylase were measured as described above. KO- TLR11−/− animals. The data shown are the mean ± SD.

TLR11-dependent pancreatitis is regulated by hematopoetically derived cells

Recent evidence has indicated that in addition to the regulation of immune responses against non-self molecules, direct TLR stimulation of epithelial and stromal cells is essential for maintaining tissue integrity. In these studies, elimination of TLR4, TLR2, or MyD88 increased both disease susceptibility and mortality in mice with DSS-induced colitis (18) or bleomycin-induced lung injury (19), and resulted in impaired liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy (20). Nevertheless, in contrast to the above models, T. gondii-induced pancreatitis in radiation chimeric mice was found to be determined by the absence of TLR11 in the hemopoetic compartment, but not in the radioresistant compartment in which pancreatic tissue resides (Fig. 2C). Thus, the disease process identified in our experiments does not appear to result from the lack of TLR-mediated protection of the target tissue.

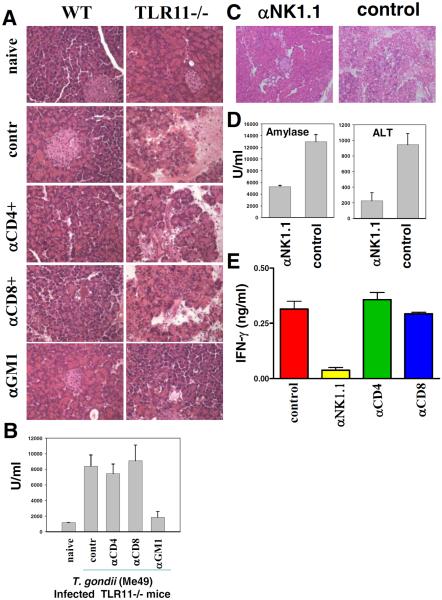

The T. gondii-induced pancreatitis occurring in TLR11−/− mice requires NK cells, but not T lymphocytes

We next sought to determine whether T. gondii-induced pancreatitis stems from a dysregulated activation of effector mechanisms normally involved in host resistance. CD4, CD8, as well as NK cells are potently and rapidly activated in T. gondii-infected animals as a consequence of the initial encounter between APCs and the parasite (21, 22). To analyze the possible pathologic role of these effector cells, we first tested the effects of CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion since TLR11 recognition of T.gondii profilin is known to regulate the specificity of the CD4+ T cell response against Ags of this parasite (23). Nevertheless, Ab-mediated elimination of CD4+ T lymphocytes failed to prevent the development of acute pancreatitis in TLR11−/− animals as judged by both histological and biochemical criteria (Fig. 3, A and B). Similarly, depletion of CD8+ T cells had no detectable effect on the induction of pancreatitis in this model. In contrast, when NK cells were depleted in T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− animals by treatment with anti-asialo GM1 or NK1.1 Abs, we observed dramatic reductions in the systemic inflammation markers AST, ALT, serum amylase, and IFN-γ (Fig. 3, B–E and data not shown). Furthermore, histological examination of pancreatic tissue sections in NK cell-depleted TLR11−/− mice confirmed the absence of detectable tissue damage (Fig. 3, A and C) and no fat necrosis was evident in the peritoneal cavities of these animals (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

NK cells play a major role in the induction of pancreatitis in response to T. gondii infection. A, WT or TLR11−/− animals were treated with the CD4, CD8, or NK cell-depleting Abs 1 day before infection and on day 3 postinfection. All animals were infected with an average of 20 cysts per mouse of the ME49 strain of T. gondii. Pancreata from naive, isotype-control, and experimental groups were removed on day 5 postinfection for histological analysis. B, Serum levels of amylase were analyzed on day 5 postinfection. C, TLR11−/− animals were treated with the anti-NK1.1 Ab and infected with 20 cysts per mouse as described earlier. Histological analysis of the pancreatic tissues was performed on day 5 postinfection. D, TLR11−/− animals were treated with the anti-NK1.1 Ab and infected with 20 cysts per mouse. Serum levels of amylase and ALT were measured on day 5 postinfection. E, T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice were treated with the CD4, CD8, or NK cell (PK136) depleting Abs 1 day before infection and on day 3 postinfection. Serum levels of IFN-γ were measured on day 5 postinfection. The data shown are representative of three experiments performed, each involving three to five animals per group.

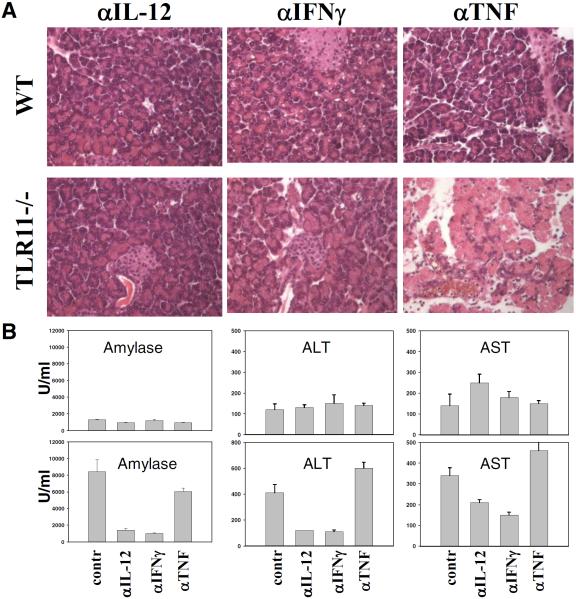

T. gondii-induced pancreatitis is the result of TLR11-independent induction of IL-12 and IFN-γ

Neutralizing Abs to IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF were next used to determine the role for these cytokines in the regulation of the NK cell-dependent pathological response. IFN-γ secretion by NK cells is thought to play a major function in host resistance against acute infection with T. gondii (24) and we hypothesized that this effector mechanism might explain the role of NK cells in the observed parasite induced tissue response. Indeed, depletion of IFN-γ completely prevented the development of pancreatitis in TLR11−/− animals (Fig. 4). Although previous studies have demonstrated that both IL-12 and TNF regulate IFN-γ production by NK cells (22), depletion of IL-12, but not TNF, inhibited the development of pancreatic pathology (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

TLR11-independent secretion of IL-12 and IFN-γ in response to T. gondii is required for acute pancreatitis and systemic inflammation. A, WT or TLR11−/− animals were treated with the anti-IL-12, anti-IFN-γ, or anti-TNF Abs and infected with 20 cysts per mouse as described earlier. Histological analysis of the pancreatic tissues was performed on day 5 postinfection. B, Serum levels of amylase, ALT, and AST were measured on day 5 postinfection. The data shown are representative of three experiments performed, each involving three to five animals per group.

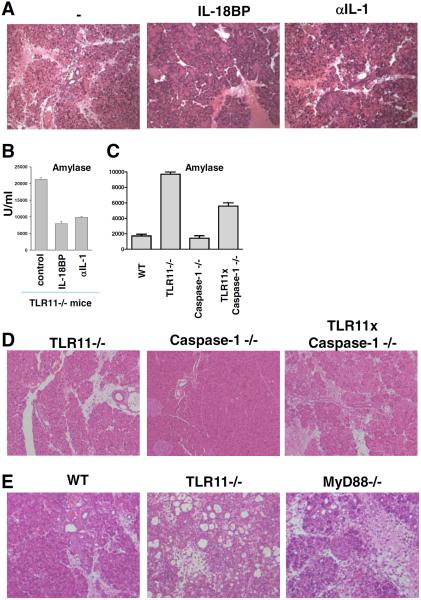

Although it has been previously established that TLR11 recognition of T. gondii profilin regulates the innate immune response to the parasite by signaling through the adaptor protein MyD88 (10), only TLR11−/−, but not MyD88−/− mice developed severe pancreatitis on day 5 postinfection (Fig. 1). The involvement of NK cells in the induction of pathology during T. gondii infections provided an explanation for this unexpected discrepancy. Thus, MyD88, in addition to regulating TLR responses, is also essential for signaling by the receptors for IL-1 and IL-18, two cytokines previously implicated in NK cell activation (24–26). Therefore, we hypothesized that in the absence of MyD88, the NK cell response required for pancreatitis might be impaired because of ablated IL-1/IL-18 signaling. Indeed, injection of T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice with either neutralizing Abs against IL-1β or IL-18 binding protein (an IL-18 antagonist) caused a marked but partial reduction in pancreatitis both histologically and as reflected in the AST, ALT, and serum amylase systemic inflammation markers (Fig. 5, A and B and data not shown). Furthermore, infection of TLR11−/− mice bred to be doubly deficient in Caspase-1, an enzyme essential for the maturation of both IL-1β and IL-18 further confirmed a role for these cytokines in the development of pancreatitis (Fig. 5, C and D). Because these TLR11 × Caspase1 doubly deficient animals developed mild but still detectable pancreatic immunopathology (Fig. 5D), we hypothesized that the previously observed lack of pancreatitis in MyD88−/− mice might stem from the particular time window in which the response was examined. Indeed, further analysis revealed that at later time points before succumbing to infection, MyD88−/− mice develop pancreatitis in response to the parasite (Fig. 5E). Thus, these data confirm that MyD88 signaling does indeed participate in the prevention of T. gondii-induced pancreatitis and suggest that the discrepancy in the kinetics of disease in the TLR11 vs MyD88−/− animals may stem from the involvement of non-TLR11-mediated MyD88 dependent signals (such as those triggered by IL-1β and IL-18) in driving early NK cell activation and pathology.

FIGURE 5.

Blocking of the TLR11-independent MyD88 activators IL-1β or IL-18 partially prevents systemic inflammation and pancreatic necrosis in TLR11−/− animals. T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice were treated with neutralizing Abs against IL-1β or IL-18BP 1 day before infection and on day 3 postinfection. Pancreata from nontreated and experimental groups were removed on day 5 postinfection for the histological analysis (A). Serum levels of amylase were analyzed on day 5 postinfection (B). C, WT, TLR11−/−, Caspase1−/−, or TLR11−/− × Caspase1−/− were infected with 20 cysts per mouse of the ME49 strain of T. gondii, and 5 days later serum levels of amylase were analyzed. D, WT, Caspase1−/−, and TLR11−/− × Caspase1−/− animals were infected as described above and pancreata were removed on day 5 postinfection for histological analysis. E, WT, TLR11−/−, and MyD88−/− animals were infected with 20 cysts per mouse of the ME49 strain of T. gondii. Pancreas sections from day 10 postinfection are shown to illustrate the late development of immunopathology in the MyD88−/− animals. The data shown are representative of three performed experiments, each involving five animals per group.

Discussion

The results presented in this study identify a novel function for TLR recognition in regulating the host protective response during microbial infection. This function prevents pathogen-induced IL-12-dependent IFN-γ-mediated damage of self tissues. In the T. gondii model studied, absence of TLR11 pattern-recognition of the parasite led to profound immunopathology affecting pancreatic and other host tissues during an acute infection time frame in which TLR11 deficiency did not result in significantly increased pathogen load. This finding is, at first glance, paradoxical since T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice were previously shown by us to display markedly reduced systemic IL-12 production (10). Nevertheless, a residual IL-12 response was observed in the TLR11−/− animals and, consistent with this observation, the knockout mice developed significantly increased IFN-γ levels. As shown in this study, this remaining IFN-γ production results in an unexpected systemic immunopathology.

Although the mechanism underlying the observed self tissue damage is likely to involve multiple cell types, including macrophages and neutrophils, the experiments presented in this study reveal NK cells as a critical component of this pathological response. NK cell activation is known to involve TLR-dependent as well as independent pathways (27, 28) and we speculate that the latter is responsible for the immunopathology seen in T. gondii-infected TLR11−/− mice. Whether the proposed pathogenic TLR-independent NK cell response is triggered by parasite or self-components remains to be determined.

At a more general level, the results presented in this study emphasize that in addition to its role in stimulating innate immunity against pathogens, TLR signaling is important in regulating the nature and target specificity of the responses induced. In this regard, it is well established that IFN-γ and other effector cytokines in addition to mediating host defense can be extremely detrimental when produced in a dysregulated manner either systemically or locally in specific tissue sites including pancreatic parenchyma (16). We hypothesize that the requirement for TLR recognition in the induction of IFN-γ responses to pathogens provides a mechanism for both directing production of the cytokine to the site of infection as well as for preventing its uncontrolled discharge in host tissues, which in the case of the T. gondii model analyzed in this study is mediated by NK cells. Studies in which pathogen-infected TLR-deficient hosts are carefully examined for immunopathological sequellae should provide a means for testing the generality of this concept.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Allen Chever for his critical insights into the nature of the tissue responses revealed in this study. We also thank G. Trinchieri, T. Wynn and M. Mentink-Kane for their discussion of the manuscript and M. Czapiga and O. Schwartz (Biological Imaging Section, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) for their expert assistance in confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

This project was supported (in part) by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases intramural program and by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Endowed Scholars Program.

Abbreviations used in this paper: DC, dendritic cell; WT, wild type; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Disclosures The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA., Jr Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science. 2002;296:298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1068883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roach JC, Glusman G, Rowen L, Kaur A, Purcell MK, Smith KD, Hood LE, Aderem A. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9577–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Crozat K, Croker B, Rutschmann S, Du X, Hoebe K. Genetic analysis of host resistance: Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:353–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reis E Sousa C. Toll-like receptors and dendritic cells: for whom the bug tolls. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Town T, Alexopoulou L, Anderson JF, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1366–1373. doi: 10.1038/nm1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Hao L, Medzhitov R. Role of Toll-like receptors in spontaneous commensal-dependent colitis. Immunity. 2006;25:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarovinsky F, Zhang D, Andersen JF, Bannenberg GL, Serhan CN, Hayden MS, Hieny S, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Ghosh S, Sher A. TLR11 activation of dendritic cells by a protozoan profilin-like protein. Science. 2005;308:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.1109893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazzinelli RT, Wysocka M, Hayashi S, Denkers EY, Hieny S, Caspar P, Trinchieri G, Sher A. Parasite-induced IL-12 stimulates early IFN-γ synthesis and resistance during acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 1994;153:2533–2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Schreiber RD, Remington JS. Interferon-γ: the major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science. 1988;240:516–518. doi: 10.1126/science.3128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger J, Remick D. Acute pancreatitis: models, markers, and mediators. Shock. 2005;24(Suppl. 1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000191413.94461.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. 2003;425:516–521. doi: 10.1038/nature01991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahuja SK, Ahuja SS, Thelmo W, Seymour A, Phelps KR. Necrotizing pancreatitis and multisystem organ failure associated with toxoplasmosis in a patient with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993;16:432–434. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parenti DM, Steinberg W, Kang P. Infectious causes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996;13:356–371. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang D, Zhang G, Hayden MS, Greenblatt MB, Bussey C, Flavell RA, Ghosh S. A toll-like receptor that prevents infection by uropathogenic bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1522–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.1094351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Iimuro Y, Naka T, Son G, Akira S, Kishimoto T, Nakanishi K, Fujimoto J. Contribution of Toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling to murine liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2005;41:443–450. doi: 10.1002/hep.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki Y, Remington JS. Dual regulation of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii infection by Lyt-2+ and Lyt-1+, L3T4+ T cells in mice. J. Immunol. 1988;140:3943–3946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sher A, Oswald IP, Hieny S, Gazzinelli RT. Toxoplasma gondii induces a T-independent IFN-γ response in natural killer cells that requires both adherent accessory cells and tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Immunol. 1993;150:3982–3989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarovinsky F, Kanzler H, Hieny S, Coffman RL, Sher A. Toll-like receptor recognition regulates immunodominance in an antimicrobial CD4+ T cell response. Immunity. 2006;25:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter CA, Chizzonite R, Remington JS. IL-1 β is required for IL-12 to induce production of IFN-γ by NK cells: a role for IL-1β in the T cell-independent mechanism of resistance against intracellular pathogens. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4347–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zitvogel L, Terme M, Borg C, Trinchieri G. Dendritic cell-NK cell cross-talk: regulation and physiopathology. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;298:157–174. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lodoen MB, Lanier L. Natural killer cells as an initial defense against pathogens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raulet DH, Vance RE. Self-tolerance of natural killer cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:520–531. doi: 10.1038/nri1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]