Abstract

Purpose of review

Renal dysplasia is classically described as a developmental disorder whereby the kidneys fail to undergo appropriate differentiation, resulting in the presence of malformed renal tissue elements. It is the commonest cause of chronic kidney disease and renal failure in the neonate. While several genes have been identified in association with renal dysplasia, the underlying molecular mechanisms are often complex and heterogeneous in nature and remain poorly understood.

Recent findings

In this review, we describe new insights into the fundamental process of normal kidney development, and how the renal cortex and medulla are patterned appropriately during gestation. We review the key genes that are indispensable for this process, and discuss how patterning of the kidney is perturbed in the absence of these signaling pathways. The recent use of whole exome sequencing has identified genetic mutations in patients with renal dysplasia, and the results of these studies have increased our understanding of the pathophysiology of renal dysplasia.

Summary

At present, there are no specific treatments available for patients with renal dysplasia. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of normal kidney development and the pathogenesis of renal dysplasia may allow for improved therapeutic options for these patients.

Keywords: renal dysplasia, whole exome sequencing, CAKUT

Introduction

Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract (CAKUT) are common congenital disorders, affecting 1 in 200 humans (1). While a wide variety of renal abnormalities are classified under CAKUT, congenital unilateral or bilateral renal dysplasia represents the most common cause of chronic kidney disease and renal failure in the neonate (2). Renal dysplasia is classically described as a developmental disorder where the kidneys fail to differentiate normally, resulting in the presence of primitive tubules, interstitial fibrosis, renal cysts and cartilage in the renal parenchyma (2). In general, renal dysplasia is thought to arise from either an intrinsic defect in the differentiation of the renal parenchyma, or as a secondary result of a functional or structural obstruction of the lower urinary tract (for example, posterior urethral valves, ureteropelvic junction obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux) (3). In contrast, renal hypoplasia refers to abnormally small kidneys (less than two standard deviations below the expected mean when correlated with age or growth parameters) with normal morphology and reduced nephron number. Current clinical practice utilizes renal ultrasonography to measure renal size and echogenicity as a means of evaluating the severity of renal hypoplasia and dysplasia. This has several limitations: 1) inability to distinguish between renal hypoplasia and dysplasia; 2) limited ability to predict renal reserve (or, the number of functioning nephrons); 3) limited information regarding the prognosis or likelihood of progression to renal failure. At present, renal transplant or dialysis are the only treatment options for renal failure, which result in significant morbidity and increased risk for mortality for patients. Given this, an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of renal dysplasia is an important prerequisite for the development of better diagnostic tools, prognostic indicators and potential novel therapies.

The underlying etiologies of renal dysplasia are complex and multifaceted, and still not fully understood (2). The heterogeneity of the phenotype likely reflects interactions amongst genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors that all impact genitourinary development. Despite this complexity, emerging information about the molecular cues and signaling pathways required for appropriate kidney development and patterning is providing significant insights into the pathogenesis of renal dysplasia.

Overview of mammalian kidney development

Mammalian kidney formation begins in the fifth week of gestation in humans, and at embryonic day 10.5 in the mouse, with the outgrowth of the ureteric bud from the Wolffian duct into the metanephric mesenchyme (Figure 1) (4,5). The subsequent formation of nephrons is classically described as dependent on reciprocal inductive signals between these two tissues. Thus, Gdnf secreted by the metanephric mesenchyme binds to its corresponding Ret tyrosine kinase receptor on the ureteric bud, and induces outgrowth and branching of the ureteric bud (6). This ultimately results in the formation of a complex ureteric tree network that gives rise to the collecting duct system. The metanephric mesenchyme condenses around each ureteric tip into a characteristic cap mesenchyme, containing Six2+/Cited1+ nephron progenitors that eventually differentiate into all other epithelial segments of the nephron following induction by Wnt9b secreted from the ureteric tips (7-9). Emerging evidence now implicates the renal stroma, which is derived from the mesenchyme adjacent to the cap mesenchyme (and is marked by the expression of FoxD1), as a third cell lineage that is crucial in nephron patterning (10-12). The renal stroma gives rise to all perivascular cells including, pericytes, glomerular mesangium, smooth muscle arterioles and renin cells (13).

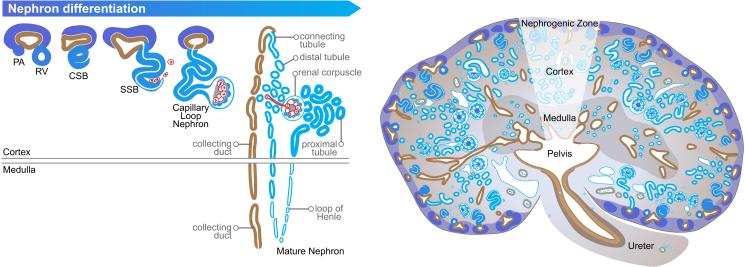

Figure 1. Nephron differentiation and patterning during kidney development.

In response to Wnt9b signaling from the ureteric tips, the surrounding nephron progenitors condense into pre-tubular aggregates (PA), and undergo a mesenchymal to epithelial transition to form the renal vesicles (RV). These RV subsequently differentiate into comma (CSB) and s-shaped bodies (SSB). Migrating perivascular cells enter into the cleft of the s-shaped bodies, followed by tubular elongation and patterning into a mature nephron with establishment of an appropriate cortical-medullary axis. Images have been obtained from the GUDMAP database (http://www.gudmap.org/Schematics). Originally designed by Kylie Georgas, University of Queensland) (5).

In response to high levels of Wnt9b, nephron progenitors condense into pre-tubular aggregates, undergoing a mesenchymal to epithelial transition into the renal vesicle, in a β-catenin dependent manner (14). As nephrogenesis proceeds, renal vesicles undergo further morphogenic changes to become comma and s-shaped bodies. At this stage, vascularization of the nephrons occurs where both endothelial and perivascular cells are recruited to the s-shaped body cleft. This generates a capillary loop nephron consisting of podocytes and fenestrated endothelium that form the glomerular filtration barrier, with its integrity supported by the glomerular mesangium. Eventually, a mature nephron is formed which consists of the glomerulus linked to the collecting duct system through differentiated epithelial segments including the proximal tubule, loops of Henle and distal tubule (15).

Molecular mechanisms of nephron progenitor self-renewal

Brenner's hypothesis postulated that individuals with a reduced nephron number at birth are at greater risk of developing hypertension and chronic kidney disease (16). It is reasonable to assume that final nephron numbers are predetermined by the number of nephron progenitors that are present during nephrogenesis (17). This assumption was confirmed in a recent study where diphtheria toxin ablation of a subset of nephron progenitors during gestation resulted in reduced nephron numbers without overt evidence of renal hypoplasia (18). Given that nephron progenitors are critical in establishing final nephron endowment, these progenitors must maintain their ability to self-renew so as to prevent premature exhaustion prior to cessation of nephrogenesis (7,9,19,20). Moreover, incorrect differentiation of nephron progenitors leads to renal dysplasia (21).

It is notable that recent studies from multiple groups have shown that the nephron progenitors appear to be more heterogeneous than previously thought. Thus, the primitive self-renewing nephron progenitors are thought to be marked by the co-expression of Six2+/Cited1+, and Six2+/Cited1− cells are thought to be more committed towards differentiation (19,20). It has been proposed that the transcription factor Six2 acts by ensuring only a fraction of the nephron progenitors become committed to differentiate after induction (9). In the undifferentiated Six2+/Cited1+ progenitors, Six2 forms a complex with Lef/Tcf factors to maintain multipotency of the nephron progenitors (19). In Six2low pretubular aggregates, this is lost upon entry of β-catenin into the complex, which subsequently promotes transcription of genes known to be critical in the mesenchymal to epithelial transition, such as Fgf8 and Wnt4 (19). Genetic deletion of Six2 from nephron progenitors resulted in severe renal hypoplasia due to ectopic renal vesicle formation, and premature exhaustion of the nephron progenitors (9). Conversely, ectopic expression of Six2 in embryonic kidney explants resulted in preservation of the nephron progenitor population and suppression of mesenchymal to epithelial transition (9).

Wnt9b has recently been shown to have a role in maintaining the multipotency of nephron progenitors, in addition to its function in inducing the nephron progenitor to commit towards differentiation (7). These divergent actions co-existing within the same cellular population are likely to be a collaborative effort between Six2 and Wnt/β-catenin regulatory mechanisms acting on cis-regulatory modules present in progenitors to suppress expression of mesenchymal to epithelial transition genes (19).

In addition to Wnt signaling, Bmp7 has been shown to not only promote self-renewal of the Six2+/Cited1+ nephron progenitors through a Mapk dependent manner, but also to induce transition of the Six2+/Cited1+ nephron progenitors to exit into a Six2+/Cited1− state via phospho-Smad1/5 activation (20). Besides Bmp7, Fgf9 and Fgf20 growth factors are also critical for nephron progenitor survival and maintenance (22). More recently, it has been demonstrated that the age of nephron progenitors affects its commitment to either stay undifferentiated, or to exit from its multipotent state (23). Specifically, elevation of mTor and reduced Fgf20 with aging appears to be the main contributory factors towards determination of nephron progenitor cell fate (23). Other key signaling pathways and transcription factors that have also been demonstrated to be indispensable for nephron progenitor maintenance include Osr1, Eya1, Wt1, Sall1, Dlg1 and Cask (24-28).

In addition to these genetic factors, microRNAs (miRNAs) have also been implicated in nephron progenitor survival and self-renewal. MiRNAs function by post-transcriptionally regulating gene expression and protein translation (29). Genetic ablation of Dicer, the endoribonuclease enzyme required for biosynthesis of miRNAs, resulted in increased apoptosis in nephron progenitors associated with elevated levels of Bcl2L11 (Bim), a pro-apoptotic protein (30,31). Loss of one specific miRNA cluster, miR-17~92, in nephron progenitors and their derivatives resulted in decreased nephron number and pathological signatures of chronic kidney disease including proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis and podocyte foot effacement (32).

Molecular mechanisms of nephron patterning

Nephron patterning into the various highly specialized segments is essential for establishing the functional role of the nephron, and abnormalities of nephron pattern result in renal dysplasia (21). Progression of pretubular aggregates into polarized renal vesicles is dependent on the hierarchal expression of Fgfrl1, Fgf8, Wnt4 and Lhx1 (33-36). Appropriate nephron patterning ensues, therefore ensuring that the various precursor cells undergo appropriate differentiation into their respective mature cell type as well as establishing the architecture of the nephron.

Both Hnf1β and Notch signaling have not only been shown to be important for nephron patterning, but also to be associated with human syndromes when mutated, renal cysts and diabetes (RCAD) and Alagille syndrome, respectively (37,38). Expression of Hnf1β within the comma and s-shaped bodies has been proposed to regulate appropriate nephron polarization patterning via the transcriptional regulation of its downstream target genes including Lfng, Dll1, Hnf4α, Cdh6, Pcsk9 and Tcfap2b and Notch-associated genes including Lfng, Dll1, Jag1 and Irx1/2 (39). Lack of Hnf1β results in a severe nephron patterning defect with rudimentary glomeruli that are connected to the collecting duct system via a short tubule (39). While renal vesicles do develop and appear to undergo appropriate polarization in the absence of Hnf1β, these structures however fail to acquire an appropriate s-shaped body pattern, followed by increased apoptosis in late stage s-shaped bodies (39). Notch signaling, specifically Notch2, has been proposed to be required for optimal s-shaped body formation, differentiation into proximal tubules and podocytes as well as maintaining the proliferation capacity of the proximal precursors (40).

As mentioned earlier, miRNAs have been implicated in nephron patterning as well. The loss of Dicer activity in the renal stroma and its cellular derivatives resulted in elevated apoptosis, renal hypodysplasia and glomerular mesangial defects due to ectopic accumulation of Bcl2L11 and p53-target genes (41). Other renal lineages which develop renal dysplasia related to a loss of Dicer activity include, ureteric bud (renal cyst due to altered oriented cell division), podocytes (podocyte foot effacement and proteinuria) and renin cells (loss of blood pressure regulation and striped fibrosis) (31,42-45).

Establishment of the cortical-medullary axis

Unlike nephrogenesis where a wealth of genetic information has been established, the current knowledge on embryonic medullary formation and its genetic regulation is somewhat limited. The current two main mechanisms established for tubular elongation of the collecting duct in the embryonic medulla include convergent-extension mediated by Wnt9b and Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) signaling-Oriented Cell Division (OCD) mediated by both Wnt7b and Wnt9b (46,47). Convergent-extension is described as the process of cytoskeletal and cell shape changes which results in dynamic cellular rearrangements and movements within the epithelial tubules (48). Such cellular reorganization leads to increased tubular length without affecting overall cell number. As the tubule elongates, it is coupled with a decrease in tubular diameter and cell number per cross-section (47).

In contrast to the process of convergent-extension, PCP signaling-OCD mediated by Wnt7b or Wnt9b directs the collecting duct cells to adopt an oriented topology such that cellular mitosis occurring in parallel to the apical-basal plane would result in tubular elongation (46,47). Studies from the Wnt7b mouse model have demonstrated that Wnt7b secretion from the collecting duct acts indirectly by first signaling to the medullary interstitium via a Wnt/β-catenin canonical pathway, followed by activation of interstitial Wnt4, Wnt5a or Wnt11 acting through the non-canonical route to regulate PCP-OCD in the collecting ducts (46).

The multifaceted genetic circuit of renal dysplasia

Given the complexity of the genetic circuitry regulating kidney development, it is no surprise that mutations in a number of the genes described above result in renal dysplasia (49). Some of these renal disorders, although not exhaustive, include Pallister-Hall Syndrome, characterized by renal agenesis or hypoplasia defects due to GLI3 mutation which disrupts Sonic hedgehog signaling and downstream genes associated with renal development such as PAX2 and SALL1 (50-52); Townes-Brocks Syndrome, characterized by renal agenesis due to SALL1 mutation which results in defective ureteric bud outgrowth (53,54); Renal Coloboma Syndrome, characterized by vesico-ureteral reflux, renal hypoplasia or agenesis due to PAX2 mutation resulting in elevated medullary apoptosis and reduced ureteric bud branching (55,56); Ochoa Syndrome, characterized by vesico-ureteral reflux, impaired urinary outflow leading to hydronephrosis due to HPSE2 mutation (57); Branchio Oto Renal Syndrome, characterized by craniofacial and renal agenesis due to haploinsufficiency in EYA1 (58); renal agenesis due to FGF20 mutation (22) and Feingold Syndrome, characterized by renal anomalies due to mutations in MIR17HG and MYCN (59).

Whole exome sequencing identifies genetic mutations in CAKUT cohort

Transgenic mouse models have served as valuable tools in understanding the fundamental processes of kidney development, as well as providing molecular insights into how renal anomalies develop when these signaling pathways are dysregulated. Based on these studies, candidate CAKUT-causing or associated genes have been shown to be of functional relevance to human health. Whole exome sequencing of CAKUT patients has now congruently provided information about genetic mutations that are associated with their renal condition including, but not limited to, BMP7, EYA1, HNF1β, NPHS1, NPHS2, PAX2, RET, ROBO2, SIX2, SALL1, WT1 (1,60). It is notable that several of these genetic mutations have functionally been validated in transgenic mouse models (Table 1). Moreover, the sequencing platform also has the capabilities of identifying novel genes associated with CAKUT. While whole exome sequencing is not a treatment for renal disease, it offers clinicians and geneticists the ability to provide a more defined clinical diagnosis (with potential prognostic implications) for CAKUT patients. Thus, this information may help to predict the likelihood of renal hypoplasia versus dysplasia, the degree of renal reserve, and likelihood of progression to renal failure.

Table 1.

Selected transgenic mice with functional relevance to human renal dysplasia.

| Gene (Disease) | Affected component | Phenotype | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hnf1β (Renal Cysts and Diabetes Syndrome) | Ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme | Medullary hypoplasia and hydronephrosis | 1. Hnf1β is thought to act upstream of Wnt9b | (39,61) |

| 2. Hnf1β nulls have defective ureteric bud branching | ||||

| 3. Wnt4Cre and Six2Cre mediated deletion of Hnf1β led to medullary hypoplasia and eventually hydronephrosis in a proportion of these mice | ||||

| 4. Glomerulus is connected to the collecting duct through a short tubule | ||||

| Hnf1β/Pax2 compound mutants | Ureteric bud | Heterozygous mutants develop medullary hypoplasia and hydronephrosis | 1. Delayed nephron and medullary interstitium patterning | (62) |

| 2. Increased apoptosis | ||||

| 3. Reduced Bmp4 and Tbx18 expression leading to ureter smooth m uscle deficiency. Hence the medullary phenotype could be a secondary defect | ||||

| Pax2 (Renal Coloboma Syndrome) | Ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme | Renal agenesis in Pax2 homozygous mutant Reduced renal calyces in Pax2 heterozygous mutants | 1. Renal defects due to dysgenesis of the ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme | (56) |

| 2. Absence of a Wolffian duct | ||||

| 3. Metanephric mesenchyme fails to undergo epithelialization | ||||

| Sall1 (Townes-Brocks Syndrome) | Nephron progenitors | Renal agenesis | 1. Failure of ureteric bud invasion | (27,54) |

| 2. Lost of downstream target genes associated with self-renewal | ||||

| Six2 (CAKUT) | Nephron progenitors | Renal hypoplasia | 1. Premature loss of nephron progenitors | (9) |

| 2. Ectopic differentiation | ||||

| Wt1 (Wilm's Tumor or renal agenesis | Nephron progenitors | Wilms tumor or renal agenesis | 1. Failure of nephron progenitors to undergo terminal differentiation | (63-66) |

| 2. Ectopic apoptosis | ||||

| Ret (CAKUT) | Ureteric bud | Renal dysplasia | Ureteric branching defects due to abnormal ureteric outgrowth | (6,67,68) |

| Eya1 (Branchio Oto Renal Syndrome) | Nephron progenitors | Renal agenesis | Lack of Eya1 results in dysregulation of Myc phosphorylation, causing cell cycle perturbations | (25,58) |

| miR-17~92 (Feingold Syndrome) | Nephron progenitors | Renal hypodysplasia | 1. Intrinsic nephron progenitor defects that are likely to be attributed by cell cycle defects. | (32,59) |

| 2. Reduced nephron endowment | ||||

| Fgf9/Fgf20 (CAKUT) | Nephron progenitors | Renal agenesis | Premature loss of nephron progenitors | (22) |

Conclusion

Renal dysplasia is a common congenital renal disorder in humans and the leading cause of renal failure in the neonate. While the pathogenesis of renal dysplasia is complex and multifaceted, there is a growing body of evidence that links genetic mutations in transcription factors, signaling pathways and miRNAs (among others) associated with kidney development in this renal disorder. The advancement of whole exome sequencing has now allowed clinicians to gain a better insight into the pathogenesis of renal dysplasia, and provide more information to patients.

Key Points.

Genetic mutations are strongly associated with renal dysplasia

Whole exome sequencing is a sensitive and powerful method of genetic diagnosis of renal dysplasia in humans

Understanding the complex mechanisms underlying renal dysplasia may aid in future targeted therapy against the disorder.

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

Dr. Ho's laboratory is supported by funding by an NIDDK R00DK087922, NIDDK R01DK103776, March of Dimes Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar Award and NIDDK Diabetic Complications Consortium grant DK076169. Dr. Yu Leng Phua is a George B. Rathmann Research Fellow supported by the ASN Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Yu Leng Phua and Dr. Jacqueline Ho have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, (18 months/ 2013-2015) have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knüppel T, et al. Prevalence of Mutations in Renal Developmental Genes in Children with Renal Hypodysplasia: Results of the Escape Study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(10):2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf AS, Price KL, Scambler PJ, et al. Evolving Concepts in Human Renal Dysplasia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2004;15(4):998–1007. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113778.06598.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ichikawa I, Kuwayama F, Pope JC, IV, et al. Paradigm Shift from Classic Anatomic Theories to Contemporary Cell Biological Views of Cakut. Kidney International. 2002;61(3):889–898. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4*.Little MH. Improving Our Resolution of Kidney Morphogenesis across Time and Space. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2015;32:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.03.001. [This review article provides a comprehensive review of mouse and human kidney development.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding SD, Armit C, Armstrong J, et al. The Gudmap Database – an Online Resource for Genitourinary Research. Development. 2011;138(13):2845–2853. doi: 10.1242/dev.063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costantini F, Shakya R. Gdnf/Ret Signaling and the Development of the Kidney. Bioessays. 2006;28(2):117–127. doi: 10.1002/bies.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karner CM, Das A, Ma Z, et al. Canonical Wnt9b Signaling Balances Progenitor Cell Expansion and Differentiation During Kidney Development. Development. 2011;138(7):1247–1257. doi: 10.1242/dev.057646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, et al. Six2 Defines and Regulates a Multipotent Self-Renewing Nephron Progenitor Population Throughout Mammalian Kidney Development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Self M, Lagutin OV, Bowling B, et al. Six2 Is Required for Suppression of Nephrogenesis and Progenitor Renewal in the Developing Kidney. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25(21):5214–5228. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10*.Das A, Tanigawa S, Karner CM, et al. Stromal–Epithelial Crosstalk Regulates Kidney Progenitor Cell Differentiation. Nature Cell Biology. 2013;15(9):1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ncb2828. [This article illustrates the contributory function of the renal stroma towards nephron progenitor maintenance.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Bagherie-Lachidan M, Reginensi A, Zaveri HP, et al. Stromal Fat4 Acts Non-Autonomously with Dachsous1/2 to Restrict the Nephron Progenitor Pool. Development. 2015 doi: 10.1242/dev.122648. [This article illustrates the contributory function of the renal stroma towards nephron progenitor maintenance.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Mao Y, Francis-West P, Irvine KD. A Fat4-Dchs1 Signal between Stromal and Cap Mesenchyme Cells Influences Nephrogenesis and Ureteric Bud Branching. Development. 2015 doi: 10.1242/dev.122630. [This article illustrates the contributory function of the renal stroma towards nephron progenitor maintenance.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi A, Mugford Joshua W, Krautzberger AM, et al. Identification of a Multipotent Self-Renewing Stromal Progenitor Population During Mammalian Kidney Organogenesis. Stem Cell Reports. 3(4):650–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J-S, Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Wnt/Β-Catenin Signaling Regulates Nephron Induction During Mouse Kidney Development. Development. 2007;134(13):2533–2539. doi: 10.1242/dev.006155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dressler GR. Advances in Early Kidney Specification, Development and Patterning. Development. 2009;136(23):3863–3874. doi: 10.1242/dev.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and Blood Pressure: Less of One, More the Other? American Journal of Hypertension. 1988;1(4 Pt 1):335–347. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Short Kieran M, Combes Alexander N, Lefevre J, et al. Global Quantification of Tissue Dynamics in the Developing Mouse Kidney. Developmental Cell. 2014;29(2):188–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.02.017. [This article provides an excellent in-depth analysis and characterization of renal development.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Cebrian C, Asai N, D'Agati V, et al. The Number of Fetal Nephron Progenitor Cells Limits Ureteric Branching and Adult Nephron Endowment. Cell Reports. 2014;7(1):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.033. [This article demonstrates the association between nephron progenitor numbers and final nephron endowment.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park J-S, Ma W, O'Brien Lori L, et al. Six2 and Wnt Regulate Self-Renewal and Commitment of Nephron Progenitors through Shared Gene Regulatory Networks. Developmental Cell. 2012;23(3):637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown AC, Muthukrishnan SD, Guay JA, et al. Role for Compartmentalization in Nephron Progenitor Differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(12):4640–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213971110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho J. The Regulation of Apoptosis in Kidney Development: Implications for Nephron Number and Pattern? Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2014:2. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barak H, Huh S-H, Chen S, et al. Fgf9 and Fgf20 Maintain the Stemness of Nephron Progenitors in Mice and Man. Developmental Cell. 2012;22(6):1191–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Brunskill Eric W, Potter SS, et al. Intrinsic Age-Dependent Changes and Cell-Cell Contacts Regulate Nephron Progenitor Lifespan. Developmental Cell. 2015;35(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Liu H, Park J-S, et al. Osr1 Acts Downstream of and Interacts Synergistically with Six2 to Maintain Nephron Progenitor Cells During Kidney Organogenesis. Development. 2014;141(7):1442–1452. doi: 10.1242/dev.103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Wong Elaine YM, Cheng C, et al. Eya1 Interacts with Six2 and Myc to Regulate Expansion of the Nephron Progenitor Pool During Nephrogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2014;31(4):434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kann M, Bae E, Lenz MO, et al. Wt1 Targets Gas1 to Maintain Nephron Progenitor Cells by Modulating Fgf Signals. Development. 2015;142(7):1254–1266. doi: 10.1242/dev.119735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanda S, Tanigawa S, Ohmori T, et al. Sall1 Maintains Nephron Progenitors and Nascent Nephrons by Acting as Both an Activator and a Repressor. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25(11):2584–2595. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn S-Y, Kim Y, Kim ST, et al. Scaffolding Proteins Dlg1 and Cask Cooperate to Maintain the Nephron Progenitor Population During Kidney Development. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2013;24(7):1127–1138. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho J, Kreidberg JA. The Long and Short of Micrornas in the Kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;23(3):400–404. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho J, Pandey P, Schatton T, et al. The Pro-Apoptotic Protein Bim Is a Microrna Target in Kidney Progenitors. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;22(6):1053–1063. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagalakshmi VK, Ren Q, Pugh MM, et al. Dicer Regulates the Development of Nephrogenic and Ureteric Compartments in the Mammalian Kidney. Kidney International. 2011;79(3):317–330. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrone AK, Stolz DB, Bastacky SI, et al. Microrna-17~92 Is Required for Nephrogenesis and Renal Function. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25(7):1440–1452. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013040390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber SD, Steinberg F, Beyeler M, et al. The Murine Fgfrl1 Receptor Is Essential for the Development of the Metanephric Kidney. Developmental Biology. 2009;335(1):106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perantoni AO, Timofeeva O, Naillat F, et al. Inactivation of Fgf8 in Early Mesoderm Reveals an Essential Role in Kidney Development. Development. 2005;132(17):3859–3871. doi: 10.1242/dev.01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Transcriptional Profiling of Wnt4 Mutant Mouse Kidneys Identifies Genes Expressed During Nephron Formation. Gene Expression Patterns. 2008;8(5):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi A, Kwan K-M, Carroll TJ, et al. Distinct and Sequential Tissue-Specific Activities of the Lim-Class Homeobox Gene Lim1 for Tubular Morphogenesis During Kidney Development. Development. 2005;132(12):2809–2823. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bingham C, Bulman MP, Ellard S, et al. Mutations in the Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-1β Gene Are Associated with Familial Hypoplastic Glomerulocystic Kidney Disease. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;68(1):219–224. doi: 10.1086/316945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heidet L, Decramer S, Pawtowski A, et al. Spectrum of Hnf1b Mutations in a Large Cohort of Patients Who Harbor Renal Diseases. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;5(6):1079–1090. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06810909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heliot C, Desgrange A, Buisson I, et al. Hnf1b Controls Proximal-Intermediate Nephron Segment Identity in Vertebrates by Regulating Notch Signalling Components and Irx1/2. Development. 2013;140(4):873–885. doi: 10.1242/dev.086538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng H-T, Kim M, Valerius MT, et al. Notch2, but Not Notch1, Is Required for Proximal Fate Acquisition in the Mammalian Nephron. Development. 2007;134(4):801–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.02773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phua YL, Chu JYS, Marrone AK, et al. Renal Stromal Mirnas Are Required for Normal Nephrogenesis and Glomerular Mesangial Survival. Physiological Reports. 2015;3(10) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harvey SJ, Jarad G, Cunningham J, et al. Podocyte-Specific Deletion of Dicer Alters Cytoskeletal Dynamics and Causes Glomerular Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(11):2150–2158. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi S, Yu L, Chiu C, et al. Podocyte-Selective Deletion of Dicer Induces Proteinuria and Glomerulosclerosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(11):2159–2169. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho J, Ng KH, Rosen S, et al. Podocyte-Specific Loss of Functional Micrornas Leads to Rapid Glomerular and Tubular Injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(11):2069–2075. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sequeira-Lopez MLS, Weatherford ET, Borges GR, et al. The Microrna-Processing Enzyme Dicer Maintains Juxtaglomerular Cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;21(3):460–467. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009090964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Carroll TJ, Rajagopal J, et al. A Wnt7b-Dependent Pathway Regulates the Orientation of Epithelial Cell Division and Establishes the Cortico-Medullary Axis of the Mammalian Kidney. Development. 2009;136(1):161–171. doi: 10.1242/dev.022087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karner CM, Chirumamilla R, Aoki S, et al. Wnt9b Signaling Regulates Planar Cell Polarity and Kidney Tubule Morphogenesis. Nature Genetics. 2009;41(7):793–799. doi: 10.1038/ng.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costantini F, Kopan R. Patterning a Complex Organ: Branching Morphogenesis and Nephron Segmentation in Kidney Development. Developmental Cell. 2010;18(5):698–712. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schedl A. Renal Abnormalities and Their Developmental Origin. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(10):791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrg2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang S, Graham JM, Olney AH, et al. Gli3 Frameshift Mutations Cause Autosomal Dominant Pallister-Hall Syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15(3):266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Böse J, Grotewold L, Rüther U. Pallister–Hall Syndrome Phenotype in Mice Mutant for Gli3. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(9):1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu MC, Mo R, Bhella S, et al. Gli3-Dependent Transcriptional Repression of Gli1, Gli2 and Kidney Patterning Genes Disrupts Renal Morphogenesis. Development. 2006;133(3):569–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.02220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohlhase J, Wischermann A, Reichenbach H, et al. Mutations in the Sall1 Putative Transcription Factor Gene Cause Townes-Brocks Syndrome. Nature Genetics. 1998;18(1):81–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishinakamura R, Matsumoto Y, Nakao K, et al. Murine Homolog of Sall1 Is Essential for Ureteric Bud Invasion in Kidney Development. Development. 2001;128(16):3105–3115. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eccles MR, Schimmenti LA. Renal-Coloboma Syndrome: A Multi-System Developmental Disorder Caused by Pax2 Mutations. Clinical Genetics. 1999;56(1):1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porteous S, Torban E, Cho N-P, et al. Primary Renal Hypoplasia in Humans and Mice with Pax2 Mutations: Evidence of Increased Apoptosis in Fetal Kidneys of Pax21neu +/− Mutant Mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daly SB, Urquhart JE, Hilton E, et al. Mutations in Hpse2 Cause Urofacial Syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;86(6):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu P-X, Adams J, Peters H, et al. Eya1-Deficient Mice Lack Ears and Kidneys and Show Abnormal Apoptosis of Organ Primordia. Nature Genetics. 1999;23(1):113–117. doi: 10.1038/12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Pontual L, Yao E, Callier P, et al. Germline Deletion of the Mir-17~92 Cluster Causes Skeletal and Growth Defects in Humans. Nature Genetics. 2011;43(10):1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/ng.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60**.Braun DA, Schueler M, Halbritter J, et al. Whole Exome Sequencing Identifies Causative Mutations in the Majority of Consanguineous or Familial Cases with Childhood-Onset Increased Renal Echogenicity. Kidney International. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.317. [This study illustrates the use of whole exome sequencing for detecting CAKUT-genetic mutations in humans.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Massa F, Garbay S, Bouvier R, et al. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1β Controls Nephron Tubular Development. Development. 2013;140(4):886–896. doi: 10.1242/dev.086546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paces-Fessy M, Fabre M, Lesaulnier C, et al. Hnf1b and Pax2 Cooperate to Control Different Pathways in Kidney and Ureter Morphogenesis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21(14):3143–3155. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartwig S, Ho J, Pandey P, et al. Genomic Characterization of Wilms' Tumor Suppressor. 1 Targets in Nephron Progenitor Cells During Kidney Development. Development. 2010;137(7):1189–1203. doi: 10.1242/dev.045732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Call KM, Glaser T, Ito CY, et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Zinc Finger Polypeptide Gene at the Human Chromosome. 11 Wilms' Tumor Locus. Cell. 1990;60(3):509–520. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90601-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gessler M, König A, Bruns GAP. The Genomic Organization and Expression of the Wt1 Gene. Genomics. 1992;12(4):807–813. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90313-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haber DA, Sohn RL, Buckler AJ, et al. Alternative Splicing and Genomic Structure of the Wilms Tumor Gene Wt1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(21):9618–9622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vega QC, Worby CA, Lechner MS, et al. Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Activates the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Ret and Promotes Kidney Morphogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(20):10657–10661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu BC, Cebrian C, Chi X, et al. Etv4 and Etv5 Are Required Downstream of Gdnf and Ret for Kidney Branching Morphogenesis. Nature Genetics. 2009;41(12):1295–1302. doi: 10.1038/ng.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]