There are many clinical presentations and subtypes of alopecia areata (AA).1, 2 One subtype, the ophiasis form, affects the occipital and parietal scalp and is often more resistant to treatment than AA monolocularis and AA multilocularis (ie, patchy AA).2 I present a case of a patient with corticosteroid-resistant ophiasis AA who had prompt regrowth with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections.

A 41-year-old woman with AA and bipolar disorder presented with concerns about poor response to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections (3 treatment sessions of 5 mg/mL; total 3 mL) and severe debilitating alterations in mood in the immediate weeks after each treatment session. Previous treatments included minoxidil and topical steroids without effect. The patient did not wish to use systemic treatments nor contact therapy (diphencyprone, anthralin). A history of patchy AA was present for over a decade but had been worsening in the past several years. Ophiasis-type AA was present for 2 years. Eyebrows, eyelashes, and nails were unaffected. Current medication included lithium, quetiapine, and lurasidone. Blood test results were normal, including platelet concentration 201 × 109/L, ferritin 72 μg/L, and thyroid-stimulating hormone 3.42 mIU/L.

Treatment was administered with autologous PRP (Arthrex Angel System, Arthrex Inc, Naples, FL) at a concentration 3.5 times above baseline using a 2% hematocrit setting. The patient's last steroid injection was 4 months prior. Briefly, 120 mL of blood was obtained from the patient using a 19-gauge butterfly needle and spun according to manufacturer's instructions. The scalp was anesthetized with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine with 0.1-mL injections made every 1 cm with use of vibratory distracting device to minimize discomfort. Thirty minutes later PRP was mixed with platelet-poor plasma to achieve a final platelet concentration 3.5 times above baseline. A total of 9 mL of PRP was injected into the 40-cm2 occipital area using a 25-gauge needle. Additional methods of platelet activation used by some physicians, including coadministration of thrombin or calcium gluconate or use of a dermaroller device, were not used in the protocol for this patient.

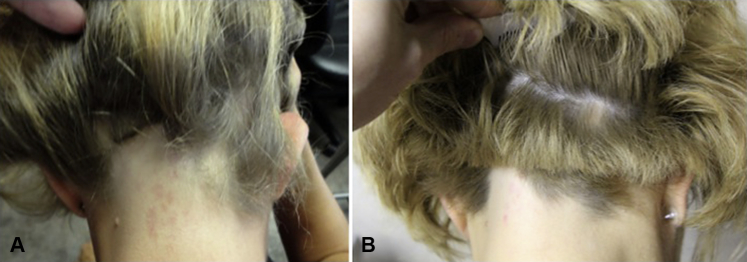

The procedure was well tolerated. Mild tenderness was present on day of the procedure and on the following 2 days but controlled with acetaminophen. Hair regrowth was noted by month 1 with robust regrowth of hairs measuring 2.8 cm by month 3 (Fig 1). The patient had no mood alterations at any period after administration of PRP.

Fig 1.

Hair regrowth in ophiasis-type alopecia areata after platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. Occipital hair loss before treatment (A) and occipital hair regrowth 3 months after administration of PRP at a concentration 3.5 times above baseline (B).

PRP represents a new and potentially effective treatment option for AA with minimal associated side effects. This case offers 2 important points: the first being the potential of PRP to treat steroid-resistant forms of AA and the second being the option to use PRP to treat AA in patients who develop limiting side effects from steroid injections.

The mechanism of PRP in the treatment of AA remains unknown, but is likely a combination of growth-stimulatory and immune-modulatory mechanisms. PRP is known to contain more than 20 growth factors3 and has beneficial effects on wound healing and hair growth.4

The effectiveness of PRP specifically in ophiasis warrants further study. A recent randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled half-head study of 45 patients with patchy AA (AA multilocularis) demonstrated that PRP was effective, and provided significantly better regrowth than 2.5 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide.5 However, that study did not address the role of PRP in ophiasis-type AA, which is more challenging to treat than patchy AA. Indeed many individuals with ophiasis-type AA, including the patient described herein, do not respond to steroid injections. The effectiveness of PRP in ophiasis-type AA and whether PRP is consistently more effective than triamcinolone acetonide in ophiasis-type AA remains unknown but warrants further study. Furthermore, the role of PRP in cases of steroid-resistant AA also warrants additional study.

Side effects from steroid injections are generally transient in nature and include local cutaneous effects such as atrophy, telangiectasia, and pigmentation changes. Systemic effects appear to be uncommon with steroid injections but studies addressing the frequency of these issues in patients with AA receiving scalp injections are lacking. In other fields of medicine, it is clear that even a single dose of steroid in the nonoral route can lead to mood changes. For example, Fishman et al6 published a report of corticosteroid-induced mania after a single regional application at the celiac plexus.

When administered via the oral route, mood changes are not uncommon. Naber et al7 reported that 26% of patients who were initially free of psychiatric illness and received short courses of high-dose prednisone for ophthalmologic disorders developed mania and 10% developed depression. The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program8 found that severe psychiatric illness occurred with a frequency of 1.3%. Mood-related side effects from oral steroids appear to be dose dependent. Given the high prevalence of mood disorders such as major depressive disorder9 and anxiety10 in patients with AA, further study is needed to evaluate the benefits of PRP for those who experience mood changes with steroid injections.

Currently, it appears that administration of PRP is not associated with many of the side effects of corticosteroids (Table I). Indeed, PRP administration to 45 patients with AA was also not associated with side effects.5 The patient presented here did not experience side effects other than transient discomfort. Importantly, she did not experience any of the mood changes she had previously experienced with steroid injections. Further study is needed to understand the short- and long-term efficacy of PRP and in the treatment of AA.

Table I.

Side effects of platelet-rich plasma injections

| Step in procedure | Side effect |

|---|---|

| Blood draw (from antecubital fossa) |

|

| Administration of local anesthetics to scalp (lidocaine with epinephrine) while centrifuging PRP |

|

| Administration of PRP |

|

| Early recovery period (first 24-48 h) |

|

| Late recovery (first 2 mo) |

|

PRP, Platelet-rich plasma.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hordinksy M.K. Overview of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S13–S15. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42–S44. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takikawa M., Nakamura S., Nakamura A. Enhanced effect of platelet rich plasma containing a new carrier on hair growth. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1721–1729. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z.J., Choi H.I., Choi D.K. Autologous platelet-rich plasma: a potential therapeutic tool for promoting hair growth. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1040–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trink A., Sorbellini E., Bezzola P. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, half-head study to evaluate the effects of platelet rich plasma on alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:690–694. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fishman S.M., Catarau E.M., Sachs G., Stojanovic M., Borsook D. Corticosteroid-induced mania after a single regional application at the celiac plexus. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1194–1196. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199611000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naber D., Sand P., Heigl B. Psychopathological and neuropsychological effects of 8-days' corticosteroid treatment: a prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program Acute adverse reactions to prednisone in relation to dosage. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972;13:694–698. doi: 10.1002/cpt1972135part1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colon E.A., Popkin M.K., Callies A.L., Dessert N.J., Hordinsky M.K. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alopecia areata. Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32:2245–2251. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90045-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo J.Y., Shellow W.V., Hallman C.P., Edwards J.E. Alopecia areata and increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:849–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]