Introduction

Chordomas are rare tumors of the bone with an average incidence of 0.1 per 100,000 per year.1 Chordomas derive from remnants of the embryonic notochord, which extends throughout the axial skeleton. The incidence of distant metastases varies, ranging between 3% and 50% among the different series.2, 3, 4 The most common sites of metastases are liver, lungs, and bones. Although skin may be often involved because of direct extension from the primary tumor or local recurrences, distant skin metastasis from chordoma is an extremely rare finding, with less than 20 cases reported in the literature. We present here the unusual case of a 45-year-old woman with skin metastasis from a sacral chondroid chordoma.

Case report

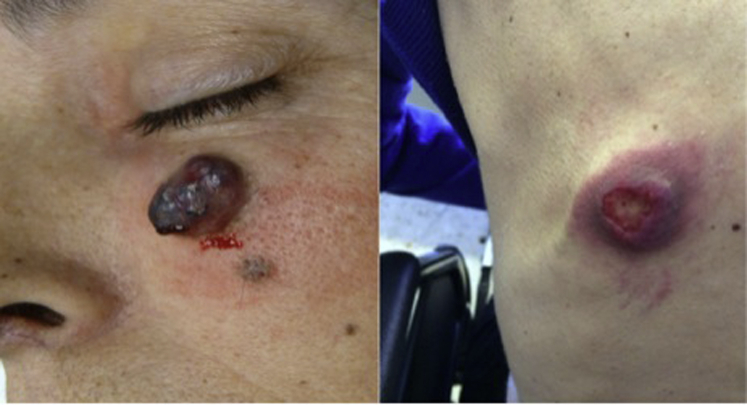

A 45-year-old woman had sacral chordoma diagnosed in 2007. She initially complained of a 2-year history of lower back pain radiating to the coccygeal and perianal region, which became increasingly worse and accompanied by hypoesthesia of the left perianal area. By the end of 2007, computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging showed a large lobulated mass extending from S2 to S5, invading the left gluteal muscle, suggesting sacral chordoma. She underwent partial sacrectomy in January 2008. The pathology report revealed a white-greyish mass that on optical microscopy showed a neoplastic proliferation of cells gathered in nests separated by fibrous septa. Most of the cells had a physaliferous cytoplasm, with sporadic cells bearing an eosinophilic cytoplasm and no mitosis. The stroma presented a mixed component with chondral characteristics. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for pancytokeratin, vimentin, and S-100 protein and focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen. Carcinoembryonic antigen and HMB-45 findings were negative. These findings were concordant with chondroid chordoma with negative margins. Eleven months after surgery, asymptomatic locoregional recurrence was found on magnetic resonance imaging. The lesion was completely excised. Pathologic findings confirmed chordoma recurrence, and adjuvant radiotherapy was administered. One year later, new locoregional recurrence and soft tissue metastasis at the L4 level were observed. The lesions were deemed unresectable, so systemic treatment with imatinib, 800 mg daily, was started. Six months later, new progression with subcutaneous soft tissue mass at the L4 level was noted. Treatment shifted to sunitinib, 37.5 mg daily, but the disease progressed 3 months later with liver, bone, and lung metastases. Third-line treatment with cisplatin, 25 mg/m2 intravenously weekly, and imatinib, 400 mg daily, was initiated. She achieved stable disease for at least 7 months. With extensive metastatic disease by September 2013, she subsequently had a firm, nontender, erythematous nodule measuring 2 × 2 cm on her left cheek (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Skin metastases from chondroid chordoma on the cheek and back.

She was referred to a dermatologist, and the lesion was excised. Pathologic examination found skin metastasis from chondroid chordoma, with immunohistochemical characteristics consistent with the primary tumor (Fig 2, Fig 3). Disease progression was observed after 7 months, and treatment with imatinib and sirolimus was commenced. Three months later, she experienced disease progression, with 2 new skin lesions on the chin and frontal area and 2 new lesions on the back (Fig 1). Erlotinib, 150 mg daily, was started. Although no significant toxicity was reported, disease progression was noted after 3 months of treatment. Best supportive care was then offered. The patient died 2 months later, 7 years after the initial diagnosis.

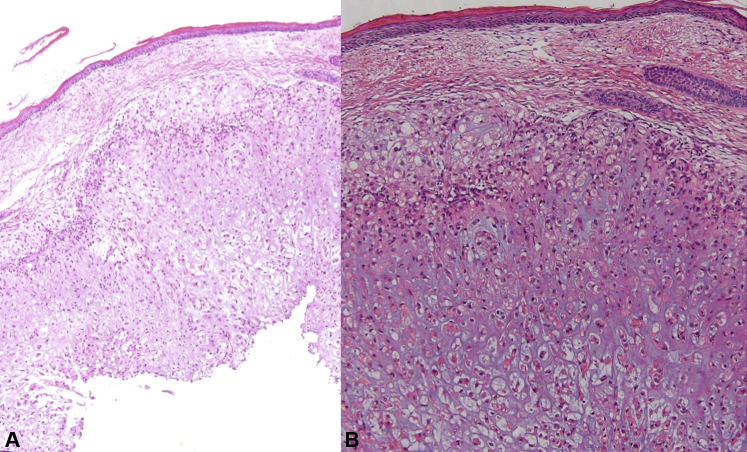

Fig 2.

Staining of skin metastasis from chondroid chordoma. A, Skin with many vacuolated cells in the dermis. B, cells present a clear cytoplasm with some cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm on a chondral stroma. Some of the cells present the characteristic physaliferous cytoplasm. (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: A, ×2; B, ×10.)

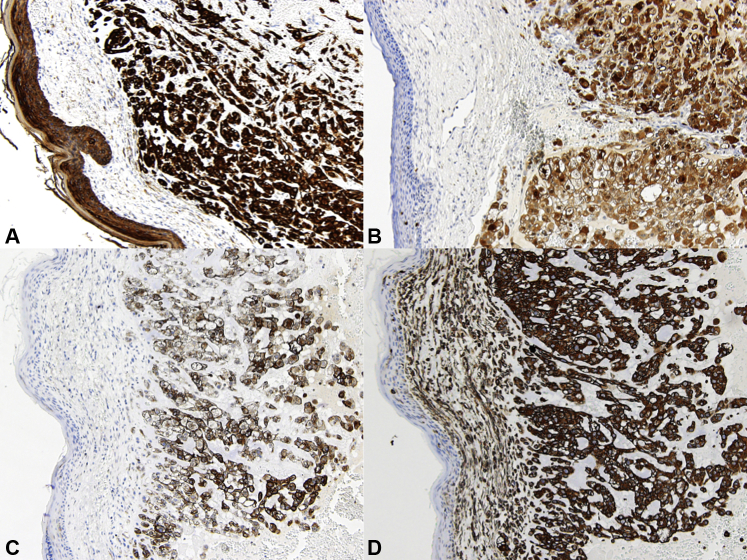

Fig 3.

Immunohistochemistry staining. Skin metastasis from chordoma positive for pancytokeratines (A), S100 (B), epithelial membrane antigen (C), and vimentin (D).

Discussion

Chordomas are low-grade, slow-growing tumors that typically remain silent until advanced stages of the disease when they present with locally aggressive behavior and clinical manifestations that vary depending on their location. Despite an increase in the last decades in the number of reports describing skin involvement in chordomas, these have been commonly related to direct invasion or locoregional involvement, whereas distant skin metastases have remained an extremely uncommon presentation in these tumors. In a retrospective study in which 207 cases were reviewed, 9% (19) of the patients had skin involvement with only 1 presenting distant skin metastasis.5 When present, a reddish, firm, nontender nodule of variable size is the most common appearance. Ulcerations may also be present. The face or back is the most common initial location, although scalp, trunk, and extremities have also been reported.6, 7, 8, 9 Although distant skin metastases may be the first symptom of the disease, they generally present as a clinical manifestation of advanced disease, when metastases in other sites are already present.

Histologically, chordomas may present as 3 different variants: classical, the most frequent variant, chondroid, with cartilage-like tissue areas, and dedifferentiated. All the previously reported cases except one were classic variants of chordoma.2

The diagnosis may be challenging because of the tumor's histologic similarities with other chondroid lesions. Differential diagnosis includes primary tumors or metastatic lesions containing a clear cell or abundant mucin component (Table I).10 Immunohistochemical staining is useful and is characterized by the tumor's reactivity to epithelial markers. Triple positivity to cytokeratins, vimentin, and S-100 is a sensitive marker in the diagnosis of this tumor, as it is present in 75% to100% of cases.11, 12 These features are usually present in metastatic lesions, although a loss of S-100 expression has occasionally been reported.6, 8 Recently, brachyury, a transcription factor that regulates the mesoderm and notochord formation in humans, has emerged as a novel biomarker to discriminate chordomas from other chondroid lesions. Sensitivity and specificity are very high and, when combined with CKs, can increase up to 98% and 100%, respectively.13

Table I.

Differential diagnosis of chordoma

Primary tumors

Metastatic tumors

|

Chordomas are locally aggressive tumors with poor long-term prognosis and a natural history of local recurrences. Classic chemotherapy shows limited efficacy. Molecular profiling shows overexpression of PDGFR-(platelet derived growth factor receptor)-β, PDGFR-α and KIT receptors with some studies showing responsiveness to imatinib alone or in combination with other drugs such as sirolimus or cisplatin.14, 15 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors like sunitinib have also shown some activity, and different molecular pathways are currently under investigation as possible targets for new treatments.16

Despite its rarity, metastases should be considered in the differential diagnosis when a new cutaneous lesion appears in a patient with chordoma. Immunohistochemical findings are crucial in the diagnosis and are usually concordant with the primary tumor. A better understanding of the molecular pathways of this disease may lead to improvements in the management of this infrequent tumor.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Newton H. Chordoma. In: Raghavan D., Brecher M.L., Johnson D.H., editors. Textbooks of uncommon cancer. 3rd ed. Wiley; Chichester: 2006. pp. 614–625. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers P.W., Schwinn C.P. Chordoma: a clinicopathologic study of metastasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;72:765–776. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/72.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjornsson J., Wold L.E., Ebersold M.J. Chordoma of the mobile spine. A clinicopathologic analysis of 40 patients. Cancer. 1993;71:735–740. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3<735::aid-cncr2820710314>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higinbotham N.L., Phillips R.F., Farr H.W. Chordoma: thirty-five years study at Memorial Hospital. Cancer. 1967;20(11):1941–1950. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196711)20:11<1841::aid-cncr2820201107>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su W.P., Louback J.B., Gagne E.J. Chordoma cutis: a report of nineteen patients with cutaneous involvement of chordoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70153-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins G.R., Essary L., Strauss J. Incidentally discovered distant cutaneous metastasis of sacral chordoma: a case with variation in S100 protein expression(compared to the primary tumor) and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:637–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persichetti G., Walling H.W., Rosen L. Chordoma cutis. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz H.A., Goldberg L.H., Humphreys T.R. Cutaneous metastasis of chordoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:259. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.09216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesinaro A.M., Maiorana A., Annessi G. Cutaneous metastasis of chordoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:603. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199512000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layfield L.J. Cytologic differential diagnosis of myxoid and mucinous neoplasms of the sacrum and parasacral soft tissues. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:264–271. doi: 10.1002/dc.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jambhekar N.A., Rekhi B., Thorat K. Revisiting chordoma with brachiury “a new age” marker. Analysis of a validation study of 51 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1181–1187. doi: 10.5858/2009-0476-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagne E.J., Su W.P. Chordoma involving the skin: an immunohistochemical study of 11 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:469–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oakley G.J., Fuhrer K., Seethala R.R. Brachyury, SOX-9, and podoplanin, new markers in the skull base chordoma vs chondrosarcoma differential: a tissue microarray-based comparative analysis. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1461–1469. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casali P.G., Messina A., Stacchiotti S. Imatinib mesylate in chordoma. Cancer. 2004;101:2086–2097. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacchiotti S., Marrari A., Tamborín E. Response to imatinib plus sirolimus in advanced chordoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1886–1894. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George S., Merriam P., Maki R.G. Multicenter phase II trial of sunitinib in the treatment of nongastrointestinal stromal tumor sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3154–3160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]