INTRODUCTION

Delirium is an acute confusional state occurring in up to 80% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients1 and has been associated with poor outcomes including difficulty weaning from the ventilator2, longer ICU length of stay (LOS)3, longer hospital LOS4, higher mortality rates5, increased dependence upon discharge from the hospital6, worse recovery one year after ICU admission6 and a 31% higher cost of hospital care7. There are no biomarkers able to predict ICU delirium and biological mechanisms responsible for delirium development remain obscure. In the absence of a clear understanding of the process which leads to delirium, it remains difficult to reduce its occurrence or design effective therapeutic interventions.

Most evidence supports a role for prolonged inflammation as a potential mechanism of delirium development. Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels have been associated with delirium in general ICU patients with a variety of diagnoses; however this evidence is conflicting as some studies have not found this association8,9. Apolipoprotein E genotype (APOE) has a role in neurodegenerative disorders, possibly by modulating neuroinflammatory responses10.

Recent literature suggests APOE genotype may be implicated in the development of ICU delirium with APOE 4 allele increasing frequency and duration of delirium11–13, however others have found no association with delirium or more general cognitive impairment14–17. Importantly, methodological differences may explain the inconsistent results of these studies and these relationships have not been explored in the context of apolipoprotein E protein (apoE) isoform or level. There are known apoE isoform specific effects on inflammation with apoE4 promoting stronger inflammatory response and increased neurotoxicity in animal18–21 and cell models22,23. An increase in apoE, or apoE 4, may promote a stronger inflammatory response, delirium presence or longer delirium duration. The purpose of this study was to determine the association between inflammatory markers, apoE protein, APOE genotype and delirium presence, delirium duration, and outcome in ICU patients.

Patients and methods

Subjects were 21–75 years old admitted to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian Hospital Medical and Surgical-Trauma ICUs requiring mechanical ventilation for 24 to 96 hours and without preadmission cognitive dysfunction. Cognitive dysfunction was identified by medical record review and interview with patient or next of kin. Data were collected for five days after study enrollment. The protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical variables were extracted from medical records; Charlson comorbidity scores24 and APACHE III scores25 were determined by project personnel. Sedative-analgesic medication data, including specific drug(s) and dose(s), were extracted for the 24 hour period before delirium assessment. A 24 hour narcotic equivalency dose (fentanyl, oxycodone, or hydromorphone), benzodiazepine equivalency dose (midazolam or lorazepam) and propofol dose were generated for use as control variables.

Delirium determination

The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) was performed daily26 and subjects with RASS scores rating between −3 to +4 underwent delirium assessment using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU)27, while the remaining patients in either RASS -4 or -5 were designated as being in a comatose state (whether disease or drug induced). All patients were thus rated as either normal (CAM-ICU negative), delirious (CAM-ICU positive and RASS -3 or higher) or comatose (RASS -4 or -5). A significant proportion of our subjects were unable to participate in the CAM-ICU due to being in a coma due to disease process or the amount of sedation required. Since coma (RASS -4 and -5) and delirium are both states of acute cognitive dysfunction in ICU patients, subjects in either coma or delirium states were included in the ‘acute brain dysfunction positive’ group for analyses (compared to the ‘CAM-ICU negative’ group).

Biomarkers

Samples were collected from existing arterial or central venous catheters. Sample dates were coded as days after admission. In some subjects (n= 10 to 55 depending upon specific biomarker) there was not enough serum collected to perform analyses of all biomarkers and analysis was done using the smaller sample.

DNA was extracted using a simple salting out procedure28. APOE genotypes were determined using standard techniques29 and genotypes were double called by individuals blinded to other data. For analyses, the sample was dichotomized based on APOE 4 allele presence (APOE4+ and APOE4−).

Daily serum apoE, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 were quantified using ELISA methodology as per manufacturer’s instructions (MBL International Corp., Watertown, MA and Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA).

Outcome measures

Days of mechanical ventilation within a 28 day period, total ICU length of stay (LOS) and total hospital LOS, mortality and discharge disposition (died, hospital inpatient, skilled nursing facility, long term acute care, rehabilitation or home) were collected from medical records.

Statistical Analyses

Measures of central tendency and dispersion were obtained for all continuous variables.. Absolute Frequency and percentage were reported for all categorical variables. Chi-square analysis was initially performed to explore the relationship between APOE genotype and delirium presence, presence of acute brain dysfunction, hospital discharge disposition, and 28 day mortality. Differences in days of mechanical ventilation, total ICU LOS, total hospital LOS and duration of delirium and acute brain dysfunction in groups based on APOE genotype, APOE 4 allele presence, delirium presence and acute brain dysfunction presence were examined with t-tests or ANOVA. Then multiple linear regression models and/or logistic regression models were used to determine relationships between predictor and outcome variables while controlling for covariates. Covariates were selected based on known relationships with outcome variables and included: age, sex, APaCHE III, Charlson Comorbidity index, 24 hour propofol dose, 24 hour narcotic dose, 24 hour benzodiazepine dose. Given the repeated measurements of delirium status, acute brain dysfunction status, daily serum apoE protein or cytokine levels over 7 days, Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) or repeated measure mixed effect modeling were used accordingly to determine the relationship between those outcomes and APOE4 allele controlling for covariates such as time-dependent sedative use.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics (including delirium and coma frequency) of the 77 enrolled subjects are presented in table 1.Acute Respiratory Failure and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were the most common admitting diagnosis (56%). Upon study enrollment, 25 (32.5%) subjects had no delirium or coma and 10 (13.0%) subjects had delirium. The majority of our sample developed delirium (45.5%) or were in a coma (31.2%) during the 5 day study period. There were 59 (76.6%) subjects in the acute brain dysfunction group (Delirium positive + Coma positive) and 18 (23.4%) in the delirium negative group. For the entire sample, average duration of delirium was 0.97 days, average number of coma days was 2.03 and average number of delirium free/coma free days was 2.0. For subjects developing delirium but not coma, average number of delirium days was 2.13 days and average number of coma free/delirium free days was 2.73 days. For subjects developing acute brain dysfunction (delirium + coma), average number of coma days was 3.7, average number of delirium days was 0.25 days and average number of coma free/delirium free days as 0.67 days.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sample by delirium groups.

| Delirium Negative (n=18) |

Delirium Positive (n=35) |

Coma Positive (n=24) |

Total (N=77) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (±SD) | 46.4 (18.3) | 47.2 (17.4) | 50.0 (15.7) | 47.9 (17.0) |

| Female n (%) | 10 (55.6) | 18 (51.4) | 13 (54.2) | 41 (53.2) |

| Race Caucasian n (%) | 17 (94.4) | 32 (91.4) | 21 (87.5) | 70 (90.9) |

| APACHE III Mean (±SD) | 59.3 (29.0) | 68.5 (26.6) | 80.6 (31.8) | 69.9 (29.51) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Mean (±SD) | 1.5 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.7) | 2.2 (2.5) | 1.9 (2.5) |

| Admission Diagnosis: Acute Respiratory Failure n (%) | 7 (38.9) | 20 (57.1) | 15 (62.5) | 42 (54.5) |

| Admission Diagnosis: Trauma n (%) | 6 (33.3) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (16.7) | 15 (19.5) |

| APOE 4 Positive n (%) | 5 (27.8) | 6 (17.1) | 6 (25.0) | 17 (22.1) |

There were no significant differences in demographic/clinical variables between the three groups. * 2 subjects had missing genotype data.

APOE genotype distribution, delirium, and demographic/clinical characteristics are presented in table 2. There were 17 subjects in the APOE4+ group and 58 subjects in the APOE4− group. There were no differences in delirium presence by APOE genotype. The APOE4+ group had shorter duration acute brain dysfunction (0.67 vs 1.43; p=.024).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sample by APOE genotype.

| APOE 2/3 (n=10) |

APOE 2/4 (n=5) |

APOE 3/3 (n=48) |

APOE 3/4 (n=12) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (±SD) | 55.0 (15.7) | 54.0 (15.0) | 44.8 (17.3) | 50.6 (17.0) |

| Female n (%) | 5 (50.0) | 2 (40.0) | 24 (50.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Race Caucasian n (%) | 10 (100.0) | 4 (80.0) | 43 (89.6) | 11 (91.7) |

| APACHE III Mean (±SD) | 58.2 (22.1) | 71.2 (20.7) | 69.2 (30.5) | 76.9 (33.3) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Mean (±SD) | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.2 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.7) | 1.6 (2.4) |

| Admission Diagnosis: Acute Respiratory Failure n (%) | 7 (70.0) | 2 (40.0) | 25 (52.1) | 7 (58.3) |

| Admission Diagnosis: Trauma n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 13 (27.1) | 1 (8.3) |

| Delirium Negative n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | 12 (66.7) | 4 (22.2 |

| Acute Brain Dysfunction Positive n (%) | 10 (16.9) | 4 (6.8) | 36 (61.0) | 8 (13.6) |

There were no differences in demographic or clinical characteristics by APOE genotype (*1 subject in each delirium group had missing genotype data). There were no APOE 2 or APOE 4 homozygotes.

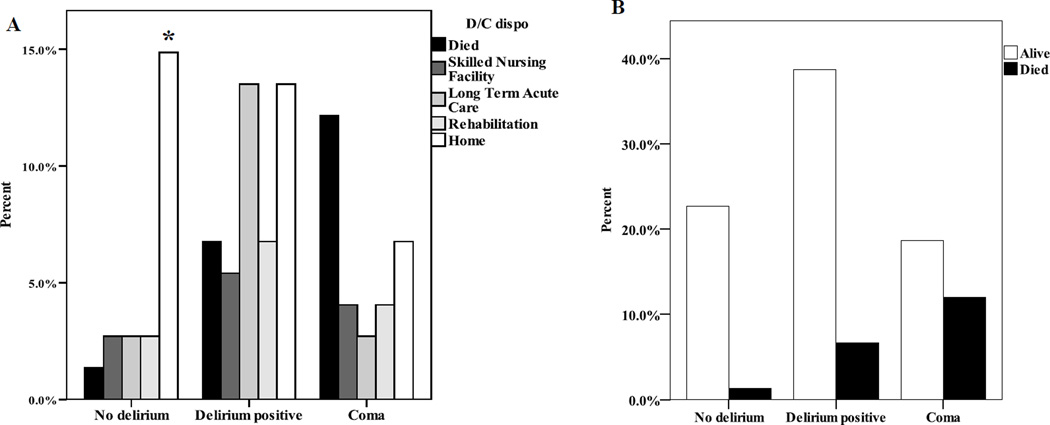

There were no differences in ICU length of stay by delirium group (p=.08), however subjects with delirium had more days of mechanical ventilation and a longer hospital length of stay compared to subjects without delirium or coma (Table 3). Subjects with coma were more likely to die than those with delirium, who were more likely to die than those without delirium or coma (Table 3). Subjects with acute brain dysfunction had 5.5 more days of mechanical ventilation (p=.027), a 5.5 day longer ICU LOS (p = .0412), and required higher level of care upon discharge (χ2 = 11.24; p=.001) (Figure 1) after controlling for covariates (age, sex, 24 hour medication dose, Charlson Comorbidity Index and APACHE III). This relationship was not modified by APOE genotype. There were no differences in days of mechanical ventilation, ICU LOS or hospital LOS between groups based on APOE genotype.

Table 3.

Outcome measures by delirium.

| No Delirium (n=18) |

Delirium Positive (n=35) |

Coma (n=24) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Ventilation daysa Mean (±SD) | 7.55 (4.20) | 14.43 (10.84) | 10.91 (8.36) |

| ICU Length of stay Mean (±SD) | 10.09 (4.40) | 16.78 (10.22) | 13.86 (11.94) |

| Hospital Length of stayb Mean (±SD) | 16.39 (6.52) | 25.09 (13.26) | 16.58 (12.67) |

| Mortalityc N (%) | 1 (5.6) | 5 (14.3) | 9 (37.5) |

There were significant differences in outcome measures by the 3 group delirium categories (no delirium, delirium positive and coma group).

p= .03.

p=.01,

p=.017.

Figure 1. Outcome measures by delirium.

Discharge disposition by Acute Brain Dysfunction. A. Percent of subjects in each discharge disposition group. Individuals without Acute Brain Dysfunction were more likely to be discharged to home. B. Percent of subjects who lived/died in each Acute Brain Dysfunction group. Note that significantly more subjects with Acute Brain Dysfunction died compared to those without dysfunction. Acute Brain Dysfunction had a negative effect on recovery such that those with Acute Brain Dysfunction were more likely to die and, for those survivors, were more likely to be discharged to a high care need facility after controlling for age, sex, 24 hour medication doses, APACHE III, and Charlson comorbidity index.

Five subjects died while on study; one in the delirium negative group (5.6%), one in the delirium group (2.9%) and 3 in the coma group (12.5%). The mortality rate was 19.5% (n=15); 5.6% (n=1) in those without delirium, 14.7% (n=5) in those with delirium and 39.1% (n=9) in those with coma. Mortality was higher in those with acute brain dysfunction compared to those without (χ2= 7.37; p=.025)(Figure 1). The mortality rate differed based on genotype with the APOE4+ group more likely to survive (χ2= 4.80; p=.028), after controlling for covariates (age, sex, 24 hour medication dose, Charlson Comorbidity Index and APACHE III) (OR = 13.565; p=.0095) and in fact all APOE4+ subjects survived.

Serum samples were available in 55 subjects (average of 4.3 per subject). Average IL-6 of the entire sample (n=38) was 182.16 p/mL at the start of the study; IL-10 (n=36) was 18.48p/mL and IL-8 (n=16) was 0.23 and apoE (n=51) was 6.48. Subjects with delirium had higher IL-6 (p=.027; n=55) (Figure 2), but not IL-10 (n=47) or IL-8 (n=10). APOE 3 homozygotes had highest IL-6 levels, followed by those with APOE 2/3, 2/4, and 3/4 genotypes (p=.05; Figure 3).

Figure 2. Mean IL-6 (±SE) over time.

Mean IL-6 (±SE) over time. A. Daily mean IL-6 in different delirium groups (CAM-ICU Negative, CAM-ICU Positive, Coma). B. Daily mean IL-6 concentrations over time by Acute Brain Dysfunction presence. IL-6 was higher in patients with delirium (CAM-ICU positive) and those with Acute Brain Dysfunction compared to those without dysfunction.

Figure 3. Mean IL-6 (±SE) over time by APOE genotype.

Mean IL-6 (±SE) over time by APOE genotype. Daily mean IL-6 in groups based on APOE genotypes by hospital day. Subjects with IL-6 was greatest in APOE 3/3 genotype > APOE 2/3 genotype > APOE 2/4 genotype > APOE 3/4 genotype.

There was no difference in apoE (n=55) over time by delirium status or APOE genotype. ApoE correlated with IL-8 (Pearson correlation = .624; p<.001) after controlling for genotype (Correlation = .653; p < .001) and delirium (Correlation = .613; p < .001). ApoE correlated weakly with IL-10 (Pearson correlation = .245; p = .009) but not IL-6, and after controlling for genotype (Correlation = .219; p = .021) and delirium (Correlation = .220; p = .019).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are: 1) delirium and acute brain dysfunction in ICU patients is associated with higher IL-6, worse outcomes, and the APOE 3/3 genotype and 2) APOE 4 allele presence was associated with shorter duration of acute brain dysfunction and decreased mortality. This is also the first study to report serum apoE levels in ICU patients.

Elevated IL-6 appears to be a hallmark of ICU delirium30 and the increased IL-6 in APOE 3/3 subjects is not particularly surprising. While all apoE isoforms are pro-inflammatory, the apoE 4 isoform is associated with the strongest inflammatory response. The APOE 4 allele correlates with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in other populations and has interactive effects with the interleukin-631 and other inflammatory genes (IL-10, HMGCR, ACT and IL-1β)32. The lack of an association between IL-10 and delirium may be related to the temporal trajectory of IL-10 after acute physiologic injury. One study found that the T-helper 2 class of chemokines were elevated early in patients with delirium 6 hours post cardiac surgery, but decreased 4 days post-operatively30. Our samples were drawn 2–9 days after admission, with higher numbers drawn closer to admission and it is possible that the peak in IL-10 that serves to dampen inflammation and stimulate immunity was not captured within our sample collection time frame. The complex response to acute illness promoting inflammation and culminating in cognitive dysfunction is likely influenced by multiple genes, their interaction and environmental factors. The lack of an association between IL-8 and delirium may be due to a small number of samples analyzed (n=10).

It is well documented that subjects who develop ICU delirium have worse outcomes6. Previous work has categorized patients with delirium together with comatose patients for some of this work and the acute brain dysfunction we describe is associated with higher mortality and worse recovery, as indicated by a higher level of care necessary upon discharge. ICU delirium leads to poorer cognitive recovery and persistent cognitive dysfunction for at least one year after admission33 and APOE 4 is associated with worse cognitive functioning in a variety of populations. APOE likely modifies cerebral acetylcholine synthesis such that the apoE 4 isoform may lead to neurotransmitter dysfunction and cognitive impairment34. In animal models, apoE-derived peptide administration impairs memory and cognitive function by blocking nicotinic acetylcholine receptors21. Our APOE 4 carriers had less delirium and a shorter duration of delirium. Much of the previous research in this area has included elderly subjects. The aging APOE 4 carrier brain may be more vulnerable and therefore more susceptible to critical illness and delirium. Indeed, in pediatric studies, APOE 4 genotype has been associated with favorable cognitive function35,36. Our study had a relatively younger population compared to previous literature and thus may be more resilient in their ability to recover regardless of genotype. The younger age of our sample may also equate to decreased morbidities that influenced our results. Additionally, there were no APOE 4/4 subjects in our sample which may have skewed results as the population with the most significant ‘gene dose’ is not represented. The complex response to critical illness leading to delirium and acute brain dysfunction and the pleiotropic role of the apoE protein in the human brain is likely a very complex relationship.

The finding that APOE 4 allele carriers had decreased mortality is a unique finding. This could have been significantly impacted by the lack of APOE 4/4 subjects and the young age of our population. The APOE 4 allele contributes to increased lipid load and may contribute to pre-admission comorbidities or in-hospital events impacting ICU recovery. This unique feature of our population makes it difficult to interpret the relationship we found between APOE genotype and mortality. Having one copy of the APOE 4 allele may not contribute enough to the pathology of delirium or acute brain dysfunction but having two copies might increase risk.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report serum apoE levels in ICU patients. There were no differences in apoE protein over time regardless of delirium status or acute brain dysfunction. Elevated apoE levels may promote inflammation resulting in acute brain dysfunction and poor outcomes in ICU patients as serum apoE protein levels correlated with IL-8 and IL-10 levels over time suggesting interaction between the apoE protein and inflammation. It is not known if apoE modifies the chemotaxic or neutrophil activating effects of IL-8 or inflammation dampening effects of IL-10. The mechanisms by which apoE protein modifies immune response are complex and most of this work has not fully evaluated genotypic/isoform specific response. ApoE synthesis is downregulated after acute inflammation, however serum levels are maintained via hepatic receptor downregulation and decreased clearance37. This mechanism may be driving the stable apoE level such that here is no change regardless of delirium. Given the small sample size, these findings need to be validated in a larger sample.

Limitations to this study may impact findings and interpretation. Our sample was small and as such findings must be interpreted carefully particularly those related to genotype and the APOE 4 allele. Five subjects died while on study, and were used for analyses but we did not consider this in our analyses. Delirium is more common in the elderly and in patients who have previous cognitive impairment. Our study criteria specifically ruled out subjects >75 years old as a method to decrease bias related to preadmission dementia or cognitive impairment. We therefore anticipated a lower rate of delirium in our sample; however 45.5% of our sample developed delirium and 76.6% had acute brain dysfunction (delirium or coma). The inclusion of subjects in coma in this study was intentional as a measure of brain dysfunction. We found similar results with and without these subjects in our analysis; however findings should be interpreted carefully because other populations may be significantly different.

We were not able to analyze all serum samples for all biomarkers due to limited volumes in some subjects. This may lead to bias in our results. Certainly these preliminary findings are of interest and support previous work; however they do need to be replicated in larger sample sizes.

Our data support an association between IL-6 and acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. The lack of an association between APOE genotype and delirium or acute brain dysfunction presence, in combination with the paradoxical relationship between APOE 4 allele presence and decreased delirium duration and improved survival found in this study with a small sample size, highlight the complexity of the relationship. These findings need to be verified in a larger sample and in the context of biological pathways of brain function and recovery in ICU patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the many ICU patients, their families, and the staff of the medical and surgical-trauma ICU’s at Presbyterian University Hospital. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (R03NR011052) and the Society for Critical Care Medicine Norma J. Shoemaker Award for Nursing Research. Dr. Kochanek was supported by NS30318.

Footnotes

Work was performed at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Contributor Information

Sheila A. Alexander, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

Dianxu Ren, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

E. Wesley Ely, Vanderbilt University.

Scott R. Gunn, University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine.

Patrick M. Kochanek, University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine.

Judith Tate, Department of Psychology.

Milos Ikonomovic, Department of Neurology.

Yvette P. Conley, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik T. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Eijk MMJ, Slooter AJC. Delirium in intensive care unit patients. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;14(2):141–147. doi: 10.1177/1089253210371495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisani MA, Arauio KL, Van Ness PH, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Innoye SK. A research algorithm to improve detection of delirium in the intensive care unit. Critical Care. 2006;10(4):R121. doi: 10.1186/cc5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, de Jonghe JFM, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428–437. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181c58715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morandi A, Brummel NE, Ely EW. Sedation, delirium and mechanical ventilation: the ‘ABCDE’ approach. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2011;17(1):43–49. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283427243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young J, Inouye SK. Delirium in older people. BMJ. 2007;334(7598):842–846. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39169.706574.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comim CM, Viela MC, Constantino CS, et al. Traffic of leukocytes and cytokine up-regulation in the central nervous system in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(4):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamis D, Treloar A, Martin FC, Gregson N, Hamilton G, Macdonald AJ. APOE and cytokines as biological markers for recovery of prevalent delirium in elderly medical inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):688–694. doi: 10.1002/gps.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vergehese PB, Castellano JM, Holtzman DM. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ely EW, Girard TD, Shintani AK, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 polymorphism as a genetic predisposition to delirium in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):112–117. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251925.18961.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung JM, Sands LP, Wang Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele increases the risk of early postoperative delirium in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2007;107(3):406–411. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278905.07899.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, Zweinderman AH, Leeflang MM, de Rooij SE. The association between delirium and the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele: new study results and a meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(10):856–862. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8c84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tagarakis GI, Tsolaki-Tagaraki F, Tsolaki M, Diegeler A, Tsilimingas NB, Papassotiropoulos A. The role of apolipoprotein E in cognitive decline and delirium after bypass heart operations. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2007;22(3):223–228. doi: 10.1177/1533317507299415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, de Rooij SE, Levi M, Zwinderman AH. The association between delirium and the apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele in the elderly. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17(5):261–266. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3280c8efd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryson GL, Wyand A, Wozny D, Rees L, Tailaard M, Nathan H. A prospective cohort study evaluating associations among delirium, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and apolipoprotein E genotype following open aortic repair. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(3):246–255. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silbert S, Evered LA, Scott DA, Cowie TF. The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele is not associated with cognitive dysfunction in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(3):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitek MP, Brown CM, Colton CA. APOE genotype-specific differences in the innate immune response. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(9):1350–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh K, Chaturvedi R, Barry DP, et al. The apolipoprotein E-mimetic peptide COG112 inhibits NF-kappaB signaling, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and disease activity in murine models of colitis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(5):3839–3850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskowitz DT, Song P, Wang H, et al. Traumatic brain injury exacerbates neurodegenerative pathology: improvement with an apolipoprotein E-based therapeutic. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(11):1983–1995. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch JR, Wang H, Mace B, et al. A novel therapeutic derived from apolipoprotein E reduces brain inflammation and improves outcome after closed head injury. Exp Neurol. 2005;192(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsoi LM, Wong KY, Liu YM, Ho YY. Apoprotein E isoform-dependent expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-6 in macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maezawa I, Nivison M, Montine KS, Maeda N, Montine TJ. Neurotoxicity from innate immune response is greatest with targeted replacement of E4 allele of apolipoprotein E gene and is mediated by microglial p38MAPK. FASEB J. 2006;20(6):797–799. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5423fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100(6):1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ely EWm, Ubiuye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(3):1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with Hha1. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(3):545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolph JL, Ramlawi B, Kuchel GA, et al. Chemokines are associated with delirium after cardiac surgery. Journals of Gerontology Series A- Biological Sceinces & Medical Sciences. 2008;63(2):184–189. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang M, Jia J. The interleukin-6 gene -572C/G promoter polymorphism modifies Alzheimer’s risk in APOE epsilon 4 carriers. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;482(3):260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Licastro F, Porcellini E, Caruso C, Lio D, Corder EH. Genetic risk profiles for Alzheimer's disease: integration of APOE genotype and variants that up-regulate inflammation. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(11):1637–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.07.007. Neurobiol Aging. 2007; 28(11): 1637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poirer J. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2003;9(3):94–101. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oria RB, Patrick PD, Zhang H, et al. APOE4 protects the cognitive development in children with heavy diarrhea burdens in Northeast Brazil. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(2):310–316. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000148719.82468.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright RO, Hu H, Silverman EK, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype predicts 24-month bayley scales infant development score. Pediatr Res. 2003;54(6) doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000090927.53818.DE. 81+9-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Thompson PA, Kitchens RL. Infection induces a positive acute phase apolipoprotein E response from a negative acute phase gene: role of hepatic LDL receptors. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(8):1782–1793. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800172-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]