Abstract

Nitrogenase is the only enzyme that can convert atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) into the biologically usable ammonia. To achieve this multi-electron redox process, the nitrogenase component proteins, MoFe-protein (MoFeP) and Fe-protein (FeP), repeatedly associate and dissociate in an ATP dependent manner, where one electron is transferred from FeP to MoFeP per association. Here, we provide evidence for the first time that encounter complexes between FeP and MoFeP play a functional role in nitrogenase turnover. The encounter complexes are stabilized by electrostatic interactions involving a positively charged patch on the β-subunit of MoFeP. Three single mutations (βAsn399Glu, βLys400Glu, and βArg401Glu) in this patch were generated in Azotobacter vinelandii MoFeP. All of the resulting variants displayed decreases in specific catalytic activity, with the βK400E mutation showing the largest effect. As simulated by the Thorneley-Lowe kinetic scheme, this single mutation lowered the rate constant for FeP-MoFeP association five-fold. We also found that the βK400E mutation did not affect the coupling of ATP hydrolysis with electron transfer (ET) between FeP and MoFeP. These data suggest a mechanism where FeP initially forms encounter complexes on the MoFeP β-subunit surface en route to the ATP-activated, ET-competent complex over the αβ-interface.

Keywords: Biological nitrogen fixation, nitrogenase, electron transfer, encounter complexes, protein-protein interactions

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

There is mounting evidence that electron transfer (ET) reactions between protein partners are complex, multi-step processes that proceed through the initial formation of a dynamic ensemble of encounter complexes. These complexes then lead to a specific, functionally active docking geometry (or geometries).1,2 In general, encounter complexes are fleeting, low-affinity species guided by long-range electrostatic interactions.1,2 In contrast, ET-active conformations are characterized by more tightly bound, stereospecific docking geometries stabilized by short-range (H-bonding, salt-bridging, hydrophobic) contacts.3,4 Encounter complexes are proposed to prolong the collisional lifetimes of protein interactions and reduce the search space for forming active complexes, thereby increasing functional efficiency.1,5 Interprotein ET reactions carry a particularly stringent requirement for fast intermolecular association and turnover. Indeed, the functional importance of encounter complexes in interprotein ET reactions has been well documented in several redox pairs such as cytochrome c (cyt c)–cyt c peroxidase,6–8 cyt b5–myoglobin,9,10 and cyt f–plastocyanin. 11–13 In this work, we establish that the complex interprotein ET interactions in the metalloenzyme nitrogenase also involve functionally relevant encounter complexes, whose active role in nitrogenase catalysis has previously been only postulated.

Nitrogenase catalyzes the 6-electron reduction of N2 to NH3 along with the obligate evolution of H2:

| (Equation 1) |

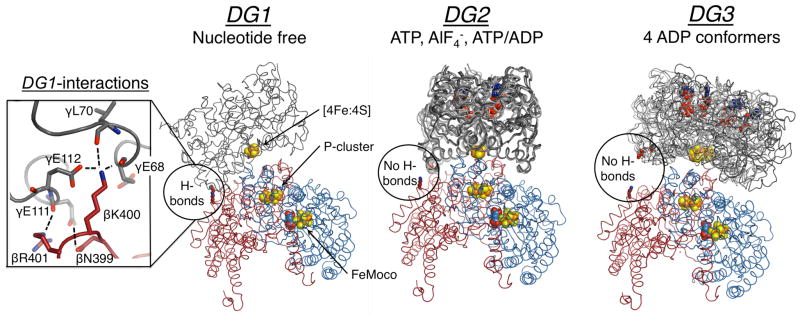

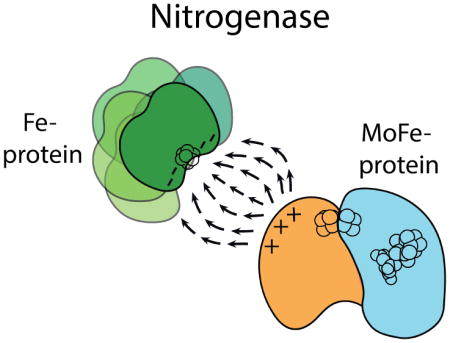

Nitrogenase consists of two redox partners (Figure 1). The MoFe-protein (MoFeP) is an α2β2 heterotetramer, which contains the P-cluster (a [8Fe:7S] cluster) and the catalytic FeMoco (a [7Fe:9S:1Mo:1C] cluster). The Fe-protein (FeP) is a γ2 homodimeric [4Fe:4S]-protein and the exclusive electron donor to MoFeP.14,15 ET from the [4Fe:4S] of FeP to the FeMoco occurs through the intermediacy of the P-cluster. Nitrogenase differs from the aforementioned protein redox pairs in that its protein-protein interactions are regulated by the ATPase activity of FeP. ATP binding and hydrolysis not only provide a timing mechanism for the successive ET-interactions between FeP and MoFeP, but likely also coordinate the downstream, multi-electron catalytic reactions. In order to elucidate the structural basis for the ATP-dependent interprotein ET processes, the FeP-MoFeP complex from Azotobacter vinelandii (Av) has been crystallographically characterized under solution conditions that mimic different stages of turnover (Figure 1).16 These structures revealed that FeP could populate three distinct docking geometries (DG) on the MoFeP surface in a nucleotide dependent manner. In this paper, we refer to these geometries as DG1, DG2, and DG3.

Figure 1.

Structures of the nucleotide free, ATP, and ADP bound nitrogenase, where FeP (γ-subunit) is grey, MoFeP α-subunit is blue, and MoFeP β-subunit is red. The location of the β399–401 surface patch is circled, and the inset on the left shows interprotein interactions in DG1. All known FeP conformations in each docking geometry are depicted. For DG1 the only available structure is shown (PDB ID: 2AFH). For DG2, AMPPCP (a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog) (PDB ID: 2AFK), ADP.AlF4− (PDB ID: 1M34), and ATP/ADP-bound (PDB ID: 4WZA) structures are shown. For DG3, all four ADP-bound FeP conformers (PDB ID: 2AFI) are overlaid. Oxygen, nitrogen, iron, and sulfur are colored red, blue, orange, and yellow, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are marked by dashed lines. Nucleotides and metal clusters are shown as spheres. Only one αβ MoFeP dimer is displayed.

Despite extensive structural data, little is known about a) the solution dynamics of FeP-MoFeP interactions, b) how these dynamics regulate ATP-coupled inter- and intra-protein ET, and c) the functional relevance of the crystallographically observed FeP-MoFeP complexes. Out of these three crystallographically observed FeP-MoFeP docking geometries, the mechanistic importance of only DG2, populated in the presence of ATP-analogs, is unambiguous.4,17 All FeP-MoFeP complexes captured in DG2 feature a short ET distance (~15–16 Å), a densely packed protein medium between the [4Fe:4S] of FeP and the P-cluster, and compact FeP conformations that are conducive to ATP hydrolysis (Figure 1). Therefore, DG2 is considered to represent the activated protein complex in which ATP hydrolysis is coupled to ET. Recent experiments suggest that ATP-driven conformational gating events within DG2 may activate the initial ET step from the all-ferrous P-cluster to the FeMoco.18–21 This step is then followed by a subsequent ET from the [4Fe:4S] of FeP to the oxidized P-cluster,22,23 in a sequence of events coupled to ATP hydrolysis. The structural details of these conformationally gated ET events within DG2 remain to be elucidated.

In contrast to DG2, DG1 features a long distance (~20 Å) and a sizeable solvent-filled gap in the intervening region between the [4Fe:4S] and the P-cluster, and FeP is found in an open conformation with well-separated nucleotide-binding pockets. Moreover, the DG1 structure was obtained in the absence of any nucleotides, which is a physiologically unlikely condition given the typical ATP and ADP concentrations under cellular turnover conditions24 and the nucleotide-binding affinities of FeP.25 Nevertheless, the binding surface between FeP and MoFeP in DG1 is extensive (~2800 Å2) and contains many short-range interactions typical of ET protein partners. In particular, a negatively charged region of FeP (γGlu68, γAsp69, γGlu111, γGlu112) forms extensive H-bonding and salt-bridging interactions with a positively charged patch on the MoFeP β-subunit surface (βAsn399, βLys400, βArg401) (Figure 1 inset). Howard and colleagues demonstrated that FeP and MoFeP form a highly specific crosslinked complex in solution between γGlu112 and βLys400 side chains mediated by 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide (EDC).26–28 The crosslinking reaction proceeded with and without nucleotides, and importantly, it did not involve other acidic or basic residues on the FeP and MoFeP surfaces. It was hypothesized that the EDC-crosslinked FeP-MoFeP complex could represent an encounter complex on the way to the formation of an ET-active complex.29 However, the functional relevance of the DG1 conformation has neither been experimentally evaluated nor included in the catalytic schemes for nitrogenase such as the Thorneley-Lowe cycle (Schemes 1, S1 and S2).30–32 To investigate if the DG1 conformation is functionally relevant, we generated MoFeP mutants aimed at destabilizing the interactions of the MoFeP β399–401 surface patch with FeP. If DG1 is relevant in turnover and populated en route to the formation of the activated DG2 state, we expected a loss of catalytic activity in the MoFeP mutants. In contrast, if the DG1 conformation represents an off-pathway complex, we expected the MoFeP mutants to have no effect, or even enhance nitrogenase activity. Our studies provide strong evidence that the electrostatic interactions stabilizing the DG1 conformation are necessary for forming “on-pathway” encounter complexes. The involvement of encounter complexes may provide a means to increase the effective association rate between FeP and MoFeP and thereby electron flux to MoFeP.

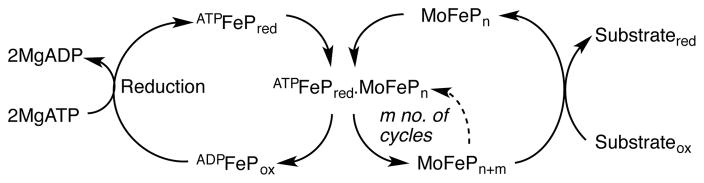

Scheme 1.

Model for nitrogenase turnover, adapted from Rees et al.14 FADP and FATP represent FeP with two nucleotides bound. The “n” subscript represents resting state MoFeP, and the “m” subscript, denotes MoFeP after receiving m electrons from FeP. Depending on the substrate, MoFeP is reduced by 2–6 electrons prior to substrate reduction. MoFeP refers to one half of the MoFeP.

RESULTS

Generation and growth of A. vinelandii β399-401 MoFeP variants

In order to probe the functional relevance of FeP-MoFeP interactions in the DG1 complex, we individually mutated the neutral βAsn399 and the positively charged βLys400 and βArg401 to negatively charged Glu. Whereas these residues make extensive contacts both with side chain and main chain atoms of FeP in DG1 (Figure 1 inset), their shortest distance to the FeP surface is ≥4.5 Å in DG2 and ≥11 Å in DG3. Thus, functional effects of βN399E, βK400E and βR401E mutations can be attributed primarily to the perturbation of the DG1 complex, or related complexes that utilize the β399-401 surface patch. A. vinelandii chromosomal mutants were generated using a previously described two-step procedure.21,33 The mutations were confirmed by gene sequencing (Figure S1), and, in the case of βK400E, also by X-ray crystallography (vide infra). All A. vinelandii strains were capable of diazotrophic growth at wild-type (WT) levels (Figure S2), suggesting that all three MoFeP variants are functional in nitrogen fixation. The variants were overexpressed using previously reported derepression strategies34 and isolated in good yields with high purity (2.1, 3.3, and 1.0 mg MoFeP per g of wet cell paste for βN399E, βK400E, and βR401E, respectively).

Crystal structure of βK400E-MoFeP

Monoclinic (P21), single crystals of βK400E-MoFeP were grown under solution conditions similar to those previously reported for WT-MoFeP. 35 The 1.75 Å-resolution structure shows that βK400E-MoFeP is isomorphous with WT-MoFeP (r.m.s.d. = 0.3 Å over all α-C’s), and there are no structural perturbations surrounding residue β E400 (Figure 2A). The electron densities for all eight βE400 side chains in the asymmetric unit are clearly visible and confirm the desired mutation (Figure S3). Despite the similarity of the crystallization conditions, the unit cell of βK400E-MoFeP (P21, 175 Å × 144 Å × 177 Å, β=114°, Table S1) is distinct from all other known A. vinelandii WT-MoFeP crystals (most common P21 unit cell: ~80 Å × 130 Å × 107 Å, β≈110°). In WT-MoFeP crystals, the βK400 side chains are well packed against negatively charged residues (αE368 and αE373) from symmetry related molecules (Figure S4A). In contrast, the βE400 side chains in the βK400E variant extend into solvent-filled spaces (the only ones of appreciable size) in the lattice, indicating that this single, charge-reversal mutation has drastically influenced protein packing interactions (Figure S4B).

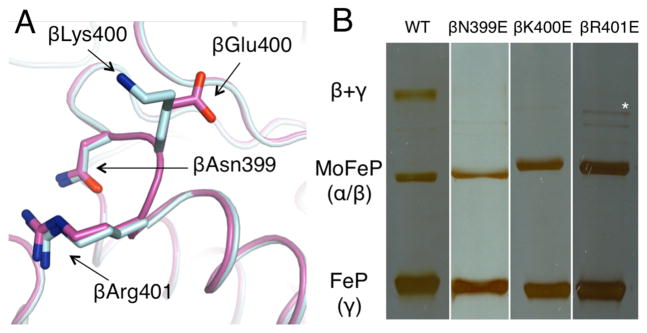

Figure 2.

(A) Crystal structure of βK400E-MoFeP (light blue) compared to WT-MoFeP (magenta). (B) SDS-PAGE gels demonstrating that only WT-MoFeP crosslinks with FeP. Full images can be found in Figure S5. The asterisk marks an impurity found in βR401E-MoFeP.

Effects of β399-401 MoFeP mutations on EDC-mediated FeP crosslinking

We examined the ability of βN399E, βK400E, and βR401E-MoFeP variants to form EDC-crosslinked complexes with FeP using previously reported conditions.26 As expected, no crosslinked complex was detected in the case of the βK400E mutation, since this mutation eliminates the amine functionality required for the specific βK400-γE112 isopeptide linkage (Figure 2B and S5). We observed the same effect when saturating concentrations of MgATP or MgADP (10 mM) were included in the crosslinking reaction (Figure S6). Howard and colleagues established βK400-γE112 as the location of crosslinking through Edman degradation,27 but they did not demonstrate that this was still the site of crosslinking in the presence of nucleotides. Since βK400E-MoFeP does not crosslink the FeP even in the presence of nucleotides, our findings provide unambiguous evidence that ADP- and ATP-bound FeP also form the specific βK400-γE112 linkage with MoFeP.

Interestingly, the extent of FeP-MoFeP crosslinking was also diminished to negligible levels with βN399E- and βR401E-MoFeP variants (Figure 2B and S5). Two possible scenarios may account for this observation. In one scenario, the charge-reversal mutations on MoFeP destabilize the H-bonding and electrostatic interactions between the two proteins. This abolishes the formation of the DG1 conformation and/or drastically curtails its lifetime, preventing EDC-mediated crosslink formation. In the other scenario, the ternary complex does form, but βN399E and βR401E mutations perturb the local structure within the complex, disrupting the stereospecific alignment of the carboxylate, carbodiimide, and amine groups needed for the selective isopeptide bond formation. Given that we do not see any level of crosslinking, we strongly favor the first scenario, i.e., mutations in the β399-401 patch on the MoFeP surface have significant effects on interactions with FeP in solution.

Effects of the β399-401 MoFeP mutations on catalytic efficiency and FeP-MoFeP interactions

To investigate the functional effects of the MoFeP β399-401 surface mutations, we assayed each mutant’s ability to reduce the alternative substrate acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) by 2 e−/2 H+ and the ability of βK400E-MoFeP to reduce H+ to H2 by 2 e− under standard conditions (Figure 3A, S7 and Table 1). The maximal specific activities of the mutants were 65%–80% of WT-MoFeP. In addition, half-maximal specific activities were reached at higher FeP concentrations in all cases (Figure 3A and S7), suggesting weaker interactions between the two proteins. The greatest effect was seen for the βK400E mutation (~65% of WT) and can be attributed to the more extensive interactions of βK400 side chain with FeP in the DG1 complex compared to βN399 and βR401 (Figure 1, inset). Given that these mutations are very far from any structural component of MoFeP or FeP with obvious functional importance (i.e., for ET, ATP hydrolysis, ATP/ET coupling, substrate diffusion, catalysis), their sizable effects on catalytic activity are remarkable.

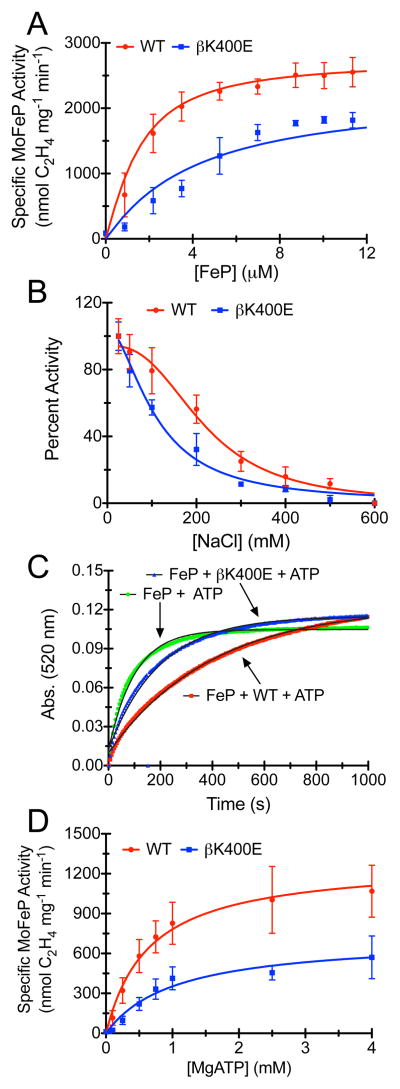

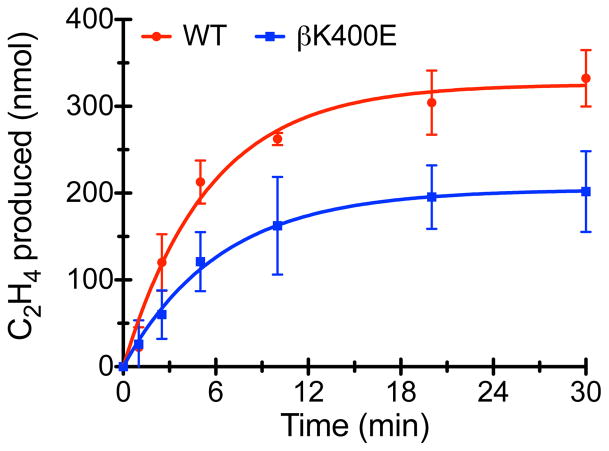

Figure 3.

(A) Nitrogenase C2H2 reduction assays for WT- and βK400E-MoFeP. The solid lines represent the Thorneley-Lowe simulation. (B) Inhibition of nitrogenase by NaCl. The solid lines represent the best-fit curves to an IC50 equation. (C) Chelation of the [4Fe:4S] cluster from ATP-bound FeP by 2,2-bipyridine in absence of MoFeP or in presence of WT-MoFeP or βK400E-MoFeP. The solid lines represent the single exponential fits of the data. Data for control experiments lacking FeP or ATP are shown in Figure S8. (D) ATP activation of WT- and βK400E-MoFeP. The lines represent the Michaelis-Menten fits of the data. A normalized version of Figure 3D can be found in Figure S9.

Table 1.

Maximum specific activities for WT-, βK400E-, βN399E-, and βR410E-MoFeP. Values are reported for 0.2 μM MoFeP and 8 μM FeP.

| C2H2 reduction (nmol mg−1min−1) | H+ reduction (nmol mg−1min−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| WT-MoFeP | 2550 ± 220 | 2890 ± 70 |

| βK400E-MoFeP | 1820 ± 120 | 1930 ± 220 |

| βN399E-MoFeP | 2060 ± 130 | not determined |

| βR401E-MoFeP | 1960 ± 210 | not determined |

Salt-inhibition experiments highlight the electrostatic nature of the functional effects of mutations. As previously documented,36–38 the specific activity of WT-MoFeP steadily decreases as the NaCl concentration in the assay solution is raised,39 with a IC50, NaCl equal to 250 ± 15 mM. For the βK400E mutant (which we used for the remaining investigations due to its largest effects), IC50, NaCl is reduced to 130 ± 30 mM, indicating increased sensitivity of FeP-MoFeP interactions due to this mutation.

If the reduced specific activity of βK400E-MoFeP is indeed a consequence of destabilized interactions with FeP, we would expect a similar effect in other assays that depend on FeP-MoFeP interactions. One such assay is the MgATP-dependent chelation of Fe(II) from the [4Fe:4S] cluster of FeP by 2,2′-bipyridine (bipy). It has been shown that MgATP binding to free FeP renders its [4Fe:4S] cluster susceptible to chelation by bipy (likely as a result of MgATP-induced conformational changes).40 The rate of Fe chelation is slowed in the presence of MoFeP, as it protects the [4Fe:4S] cluster through docking interactions.38,41 It is likely that this protection is achieved only within the ATP-activated DG2 state, which provides the only docking arrangement between FeP and MoFeP wherein the [4Fe:4S] is protected from the solvent (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 3C, the apparent first-order rate constant of Fe chelation from FeP in the presence of ATP decreases from 9.9 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1 to 2.5 ± 0.3 × 10−3 s−1 upon addition of WT-MoFeP, but only to 5.3 ± 0.2 × 10−3 s−1 in the case of βK400E-MoFeP under the same conditions.42 No significant Fe chelation is observed in the absence of MgATP, as expected (Figure S8). The observation that βK400E-MoFeP does not protect FeP from chelation as effectively as WT-MoFeP suggests that interactions between FeP and MoFeP are weakened by the βK400E mutation. Since the Fe-chelation assay is conducted under turnover conditions, this finding further supports the proposal that the interactions between FeP and the β399-401 MoFeP surface patch (and by inference, DG1) are populated en route to the formation of the ATP-activated DG2.

To examine the effects of the βK400E mutation on ATP-dependent substrate activation, we measured C2H2 reduction activity at a constant FeP:MoFeP ratio as a function of ATP concentration. As shown in Figures 3D and S9, the ATP-dependence of the reaction shifts to higher ATP concentrations for the βK400E mutant compared to WT-MoFeP. The resulting traces can be fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation with the assumption that ATP is the substrate in this reaction. At saturating ATP concentrations, the maximal activity (Vmax) of βK400E-MoFeP is lower than that of WT-MoFeP, reflective of the mutant’s lower specific activity. The apparent Km of 1.04 ± 0.23 mM for βK400E-MoFeP is nearly double that of 0.65 ± 0.11 mM for WT-MoFeP. These apparent Km’s are not true Michaelis constants due to the multidimensionality of the nitrogenase reaction coordinate. Nevertheless, they provide a measure of how readily the activated DG2 conformation assembles from FeP and MoFeP in the presence of ATP, suggesting again that βK400E mutation has a detrimental effect on formation of the activated DG2 complex.

Effects of the βK400E mutation on ATP hydrolysis and ET coupling

Given the complex nature of FeP-MoFeP interactions and the ensuing redox processes, the decreased activities of MoFeP variants could stem from the perturbation of any of multiple steps during turnover, i.e. protein-protein association and dissociation, ATP binding and hydrolysis, ET, or substrate reduction. One way to probe the functional importance of a mutation in nitrogenase is to evaluate the degree of coupling between ATP hydrolysis and electrons transferred to substrate. If a mutation does not directly influence the reaction coordinates for these processes, the ratio for ATP/e− coupling should approach a value of 2 (Equation 1). On the other hand, if the mutation does affect ATP/e− coupling, the ratio increases, indicating that not every ATP hydrolysis event promotes productive ET. For example, mutation of residues that are directly involved in protein-protein interactions in the activated DG2 complex (FeP: γR140Q,38 γK143Q,38 γR100H37 or MoFeP: αF125A, αF125A43) or are implicated in substrate reduction (MoFeP: αH195Q44) lead to significantly elevated ATP/e− ratios ranging from 3 to as high as 31. We observed that the ATP/e− coupling ratios for βK400E-MoFeP are indistinguishable from those of WT-MoFeP (Table 2), and consistent with ATP/e− values measured by others for WT-MoFeP under the given experimental conditions (30 °C, 13 mM Na2S2O4). These results suggest that the βK400E mutation does not perturb the activated DG2 complex or any ATP hydrolysis/redox-related process taking place within this complex. Thus, it must influence a step that either precedes or follows ATP/e− coupling, such as the formation of FeP-MoFeP encounter complexes.

Table 2.

Ratio of ATP hydrolyzed per electron transferred to product with sodium dithionite as FeP reductant.

| Ratio MoFeP:FeP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4:1 | 1:1 | 1:10 | |

| WT-MoFeP | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.5 |

| βK400E-MoFeP | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

Lastly, we measured the kinetics of irreversible inhibition of nitrogenase catalysis by aluminum tetrafluoride (AlF4−). During ATP hydrolysis, AlF4− replaces the leaving γ-phosphate group and locks the FeP-MoFeP complex into a kinetically stable DG2 conformation (τ1/2>21 h) as an ADP.AlF4− adduct.4 AlF4− has been shown to act as a slow inhibitor of nitrogenase catalysis where the rate-limiting step is the binding of AlF4− to the activated DG2 state (rather than the formation of DG2).45–47 Time-course experiments for C2H4 evolution in the presence of AlF4− indicate that the initial enzymatic velocity of the βK400E variant is lower than that for WT-MoFeP (32 ± 5 nmol min−1 vs. 59 ± 5 nmol min−1, respectively), in accordance with the lower specific activity of βK400E-MoFeP (Figure 4). In contrast, the rates of AlF4− inhibition are indistinguishable for both species (0.16 ± 0.03 min−1 and 0.18 ± 0.02 min−1, respectively), which is consistent with the expectation that the βK400E mutation should not alter the rate-limiting step for AlF4− inhibition.

Figure 4.

AlF4− inhibition of nitrogenase turnover, where the data are fit to a slow inhibitor model (solid lines).

Effects of the βK400E mutation on the FeP-MoFeP association rates

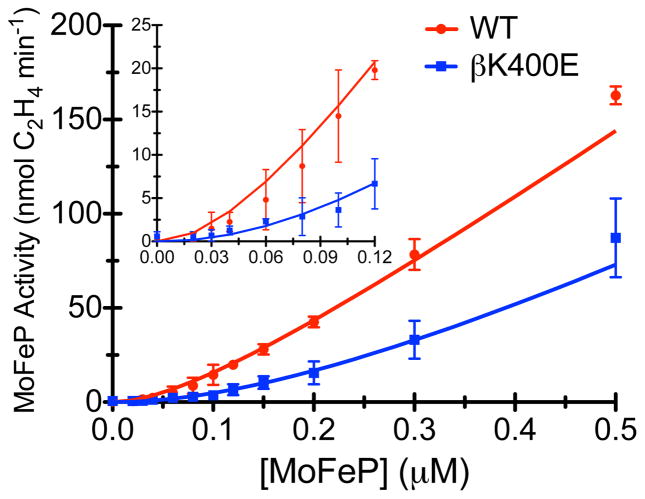

The results thus far indicate that a) the role of the β399-401 patch on the MoFeP surface is to promote association with FeP to form functionally important encounter complexes, and b) the crystallographically observed DG1 complex likely is one such encounter complex populated before commitment to the ET-competent DG2 state. We thus set out to determine the effective association rate between FeP and MoFeP through dilution experiments, which were originally reported by Thorneley and Lowe (for Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) nitrogenase).48 In dilution experiments, nitrogenase catalytic activity is measured at progressively lower FeP and MoFeP concentrations at constant FeP:MoFeP protein ratios. At sufficiently low concentrations, protein-protein association becomes the rate-limiting step, which is manifested in a sigmoidal concentration-dependent activity profile at concentrations below the protein-protein dissociation constant (Kd) and a linear increase in activity at concentrations above the Kd. Dilution experiments with WT- and βK400E-MoFeP show that the deleterious functional effect of the βK400E mutation becomes highly pronounced at low protein concentrations (Figure 5, S10 and Table S2). No measurable activity is observed with the βK400E variant until a MoFeP concentration of 0.06 μM is reached; at 0.10 μM at βK400E-MoFeP displays only 25% of WT-activity, and at 0.50 μM, 50% of WT-activity (Table S2). Quantitative estimates for apparent FeP-MoFeP association rate constants (k1) were obtained for both variants by simulating best-fit curves based on a Thorneley-Lowe model for C2H2 reduction (Schemes 1, S1 and S2).32,49 The simulatione were carried out by numerically solving the Thorneley-Lowe model for all reactants using an adapted version of a Mathematica script originally written by Watt and colleagues (see SI for the script and Table S3 for the parameters used).32 In these simulations, k1 was the only variable parameter. While the βK400E mutation may affect both the association rate constant, k1, and dissociation rate constant, k−1 for the FeP-MoFeP encounter complexes, previous work indicates that k1 is the dominating factor in dilution experiment simulations and that altering k−1 has little influence.32,50 We confirmed this observation, since altering k−1 by one order of magnitude above or below its published value causes little change in the simulation (Figure S10). Best estimates for k1 were obtained using a manual grid search procedure that yielded k1 = 2.5 × 107 M−1s−1 for WT-MoFeP and 0.5 × 107 M−1s−1 for βK400E-MoFeP, indicating a 5-fold difference in FeP-MoFeP association kinetics due to a single mutation (Figure S10 contains representative intervals for k1 used in the grid search). We then used the k1 values to simulate the C2H2 reduction experiments displayed in Figure 3A, which were conducted under significantly higher FeP/MoFeP ratios than the dilution experiments. The simulated curves describe the experimental turnover data well, validating our derived k1 values.

Figure 5.

Catalytic activity under dilution conditions for WT- and βK400E-MoFeP. The solid lines represent the Thorneley-Lowe simulations used to determine k1.

DISCUSSION

Guided by previous crosslinking studies and the crystal structure of the DG1 complex, we examined the functional significance of the positively charged β399-401 patch on the MoFeP surface. In summary, our results indicate the following:

FeP interaction with the β399-401 patch of MoFeP is largely electrostatic in nature, as evidenced by the NaCl inhibition experiments and the structure of the DG1 complex itself.

Interactions involving the MoFeP β399-401 patch and FeP are functionally important for nitrogenase catalysis and are populated along a productive reaction pathway. They serve to increase the association rate constant between FeP and MoFeP.

Interactions between the MoFeP β399-401 patch and FeP are not operative during ATP/ET coupling processes that take place within the activated complex.

All of these features are characteristic of dynamic encounter complexes, which have been implicated in many protein-protein interactions of ET partners,1,6,51 as well as those that are regulated by nucleotide binding and hydrolysis.52,53

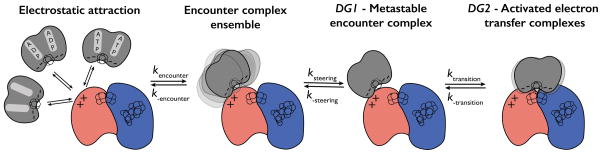

Our data, coupled with the available structural information, suggest a new picture regarding the initial steps of nitrogenase turnover (Figure 6). Based on comparison with encounter complexes described in the literature,2,54 formation of the DG1 conformation is likely a multistep process. We postulate that FeP and MoFeP first form an ensemble of loosely bound, electrostatically guided complexes centered at the β399-401 patch, with the corresponding association and dissociation rates, kencounter and k−encounter. These complexes are steered to the metastable and crystallographically tractable DG1 complex via the forward rate constant ksteering.54,55 The DG1 complex then transitions to the activated DG2 conformation via ktransition, in a step that likely involves a 2D conformational sampling of the MoFeP surface, as described in other encounter complexes.1,5,54 It is important to note here that in the Thorneley-Lowe scheme, the association rate constant k1 corresponds to the direct formation of the activated ATP-FeP-MoFeP complex (DG2) from ATP-bound FeP and MoFeP; any encounter complexes/intermediates are not invoked. Thus, the rate constant, k1, that we derive from our experiments is a composite of all forward rates kencounter, ksteering and ktransition. Further experiments are required to determine whether mutations in DG1 influence only kencounter or also ksteering and ktransition and their reverse rates. Once in the activated DG2 state, the complex is committed to ATP-coupled ET and the ensuing catalytic reactions. Compared to the DG1-centered encounter complexes, DG2 represents a relatively long-lived docking geometry, in which FeP is locked in place but still structurally dynamic,16 which may allow conformationally gated ET events within MoFeP to occur.18–21 Finally, after ATP hydrolysis and the release of phosphates, the ADP-bound complex relaxes from the DG2 into a fluid ensemble of DG3-like, dissociative states (Figure 1; not shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model for the initial steps of the complex formation between FeP and MoFeP. Initial encounter of FeP with MoFeP results in loosely bound encounter complexes, which can either dissociate into the component proteins or form the metastable DG1 conformation and subsequently the long-lived DG2 conformation. The rate constants, kencounter, ksteering and ktransition and their respective reverse rate constants represent the microscopic rates for the forward and reverse reaction, where the magnitude of the individual microscopic rates is not known. The β399-401 patch is represented by the “+” signs and residue γE112 and surrounding residues by a “−” sign.

The DG1 conformation stands out when compared to other encounter complexes described in literature. Its unusually large protein-protein interaction surface16 is more typical of activated complexes than transient encounter complexes. This feature likely renders the DG1 conformation long-lived enough to be crystallized, which is uncommon for most encounter complexes.7,56 The fact that the small β399-401 patch in Av-nitrogenase is functionally important could not have been predicted from sequence analysis, as this patch is not conserved among various nitrogenases.57 However, since encounter complexes by definition do not require geometric specificity for their formation, there is also no requirement for the strict conservation of specific surface residues so long as complementary/attractive surfaces are present. Characterizing nitrogenases from different organisms may yield interesting insights as to whether FeP binding to MoFeP via β-subunit encounter complexes is part of a consensus nitrogenase mechanism, or a special case that serves to enhance turnover in the exceptionally active Av-nitrogenase.

It is plausible that Av-MoFeP evolved a dedicated FeP docking region to decrease the amount of surface area FeP needs to sample before attaining the activated DG2 conformation. This interpretation is consistent with recent data showing that encounter complexes, in certain cases, only explore a small portion of the total available protein-protein interaction surface area.7 Furthermore, the transitions between the encounter complex(es) and active complex occur along preferred pathways and feature smooth conformational energy landscapes.1,58 Thus, rapid FeP binding to the β399-401 patch may enhance the rate of turnover by efficient funneling of FeP to the activated DG2 conformation, thereby increasing the resulting electron flux to MoFeP. The importance of the β399-401 “hotspot” in maintaining electron flux becomes particularly evident when considering in vivo turnover conditions. The ionic strength inside bacterial cells (estimated at about 150 mM)2 is considerably higher than standard assay conditions for in vitro nitrogenase experiments (typically <100 mM). Moreover, the FeP/MoFeP molar ratio in Av is approximately 1–2,59,60 whereas maximum specific activity values in literature are reported for molar ratios between 20–40. βK400E-MoFeP is much more sensitive towards high ionic strength than WT-MoFeP, as shown by NaCl inhibition experiments, and the deleterious effect of the βK400E mutation is most pronounced when FeP/MoFeP ratio is low (as manifested in turnover and dilution experiments). Therefore, the β399-401 patch may have evolved to permit efficient turnover under in vivo conditions.

Aside from enhancing FeP-MoFeP association, the DG1 docking geometry may have potential implications for other aspects of the nitrogenase mechanism. Conformational changes during transition from DG1 to DG2, for example, may play additional roles in ET-gating or substrate binding. Furthermore, under high-flux turnover conditions, where release of ADP-bound FeP from DG3 becomes rate limiting,32 FeP binding to DG1 may play a role in displacing “spent” FeP from DG3.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Reagents

Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents were acquired from Fisher Scientific, Sigma Aldrich, or VWR international.

Growth media

A. vinelandii cells were grown in liquid Burke’s medium (BM) containing 0.2% sucrose, 0.9 mM CaCl2, 1.67 mM MgSO4, 0.035 mM FeSO4, 0.002 mM Na2Mo2O4, 181 mM C6H8O7, 10 mM Na3PO4 pH 7.4. For nitrogen-containing Burke’s medium (BM+), NH4Cl was added to a concentration of 10 mM. Solid medium also included 0.4 g/L agar.

A. vinelandii mutagenesis

Mutations coding for βN399E-, βK400E-, and βR401E-MoFeP were introduced into a plasmid based on the pGEMT(Easy) plasmid (Promega), which can replicate in E. coli but not in Av. The plasmid contained the C-terminal region of A. vinelandii nifD, nifK, and the N-terminal region of nifT. Mutations were introduced into E. coli XL1 Blue using the Stratagene site directed mutagenesis kit using the following primers:

βN399E: FW: 5′ TCTCTGCCACAACGGCGAGAAGCGTTGGAAGAAGG,

REV: 5′ CCTTCTTCCAACGCTTCTCGCCGTTGTGGCAGAGA

βK400E: FW: 5′ CCTTCTTCCAACGCTTCTCGCCGTTGTGGCAGAGA,

REV: 5′ CCTTCTTCCAACGCTCGTTGCCGTTGTGGCA

βR401E: FW: 5′ GCCACAACGGCAACAAGGAGTGGAAGAAGGCGGTCGA,

REV: 5′TCGACCGCCTTCTTCCACTCCTTGTTGCCGTTGTGGC

In addition, a nifK inactivating plasmid was generated, where the entire DNA sequence coding for β399-401 was deleted and a frameshift introduced immediately before the codon coding for β399 using the following primers:

FW: 5′ CTCTGCCACAACGGTGGAAGAAGGCGGTC,

REV: 5′ GACCGCCTTCTTCCACCGTTGTGGCAGCAGAG

Genomic A. vinelandii mutations were generated in a two-step procedure as previously described.21 First, the nifK inactivating plasmid was introduced into A. vinelandii according to a modified version of the iron starvation procedure of Page and von Tigerstrom.33,61 Bacteria that underwent allelic exchange lacked a functional copy of nifK and were identified by their inability to grow in absence of a fixed nitrogen source. The presence of the partial nifK deletion was verified by sequencing the genomic DNA obtained from colony PCR (Epicentre Biotechnology Failsafe Kit). In the second step, plasmids harboring the respective mutation were introduced into the A. vinelandii nifK partial deletion strain using the iron starvation method. The bacteria that underwent allelic exchange were selected by their ability to grow on nitrogen-free BM. Stability of the mutation was assured by repeated passaging on nitrogen free BM and genomic DNA sequencing (Figure S1).

A. vinelandii growth and harvesting

Cells were first grown in a 100-mL BM+ starter culture for 16 h, then 10 mL was transferred to a 1 L BM+ starter culture for fermenter growth. Cells used for nitrogenase expression were grown in 60 L fermenter (New Brunswick Scientific) containing BM with 3 mM NH4Cl. The fermenter growth was initiated with 0.4 L of the 1 L starter culture. Nitrogenase activity was monitored through C2H2 reduction experiments (Figure S2), and cells harvested when nitrogenase activity peaked. Bacteria were harvested by concentration to approximately 3–4 L using a Pellicon 2 tangential flow membrane (Eppendorf), followed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm to obtain an approximately 80–100 g pellet.

Cell lysis and protein purification

All lysis and purification procedures were conducted on a Schlenk line under Ar or inside a glovebox under 90% Ar, 10% H2. Degassed cells were twice resuspended in a buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 8.2, 100 mM NaCl, 40% glycerol, 5 mM sodium dithionite) and pelleted at 12000 rpm. Swollen cells were resuspended in a second buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 8.2, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM sodium dithionite) and lysed by rapidly shaking the cells with glass marbles. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12500 rpm. The black supernatant was loaded onto a DEAE Sepharose column and washed with 1–1.5 L of a buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 7.75, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM sodium dithionite). Protein was eluted via a linear gradient using a buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 7.75, 5 mM sodium dithionite), where the NaCl concentration was increased from 100 mM to 500 mM. MoFeP and FeP eluted at 250 mM NaCl and 325 mM NaCl, respectively. Fractions containing MoFeP and FeP were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), pooled, and concentrated using an Amicon concentrator (Millipore). Proteins were further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Sepharose 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with a buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM sodium dithionite). Fractions containing the respective protein were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled, concentrated, and stored in liquid nitrogen in small aliquots.

EDC crosslinking

Initial crosslinking experiments with all mutants and WT-nitrogenase in the absence of nucleotides were conducted with 7.5 μM MoFeP (1.72 mg/mL), 45 μM FeP (2.7 mg/mL), and 12.5 mM EDC in a buffered solution containing 25 mM Hepes, pH 8, 60 mM NaCl, and 12.5 mM Na2S2O4 under H+ reduction conditions. The reaction was quenched by diluting a 10 μL aliquot into 200 μL of 200 mM NaC2H3O2. Samples in the presence of nucleotides were analyzed under the same conditions. However, the protein concentrations were 5.2 μM (1.2 mg/L) for MoFeP and 33 μM (2 mg/mL) for FeP. Samples were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining.

Nitrogenase activity assays

All experiments were conducted, unless otherwise noted, under an Ar atmosphere in a buffered solution containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8, 60 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 30 mM creatine phosphate, 0.00125 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase, and 13 mM Na2S2O4. The reactions were carried out in stoppered 14 mL vials at 303 K for 10 min, and they were terminated by addition of 0.3 mL glacial acetic acid. The protein concentrations were determined via Fe chelation in 6.4 M guanidine HCl by 2,2-bipyridine using an extinction coefficient of 8650 M−1cm−1 at 522 nm. All reported measurements represent the average of at least three independent measurements, and error bars represent one standard deviation. Data were analyzed and graphed using Graphpad Prism.

C2H2 reduction activity

The MoFeP concentration in the assay was 0.2 μM and the FeP concentrations varied between 0 and 12 μM. Assay vials contained a final pressure of 0.072 atm C2H2. C2H4 evolution was measured with an SRI 8610C gas chromatograph (GC) containing an alumina column (Alltech) and an FID detector, where 50 μL of the headspace was injected into the GC. The C2H4 standard was generated by filling an evacuated 250 mL flask to approximately 1 atm C2H4 (Airgas) and weighing the contents of the flask on an analytical balance. From this flask, 0.04 mL of gas was transferred to a sealed 24 mL glass vial to construct the standard curve.

H+ reduction activity

The assay was conducted with MoFeP and FeP concentrations of 0.2 μM and 8 μM, respectively. The duration of the assay was 15 min. H2 evolution was measured with an SRI 8610C gas chromatograph (GC) containing a molecular sieves column (Alltech) and a TCD detector, where 500 μL of the headspace was injected into the GC. A H2 standard curve was generated by filling a 250 mL flask with a gas mixture containing 10% H2 and 90% Ar (Praxair) and weighing the contents on an analytical balance. The standard curve was constructed directly from this flask.

NaCl inhibition

NaCl inhibition was studied by measuring C2H4 formation at a constant protein concentration (0.2 μM MoFeP and 2 μM FeP) at increasing concentrations of NaCl, where the concentration of NaCl was adjusted by adding NaCl to standard reaction buffer from a stock solution. The data was fit to following IC50 equation: , where IC50 is the NaCl concentration at which activity is half-maximal, and n is equal to the Hill coefficient. In the figure, the fit was converted from log to linear scale for clarity, and the data normalized, such that the most active data point for WT and β K400-MoFeP, respectively, is set equal to 100%, and the least active to 0%.

Fe chelation

Fe chelation was carried out in the presence of 6.25 mM 2,2-bipyridine under H+ reduction conditions, in the absence of C2H2, and in an anaerobic quartz cuvette. The reaction progress was monitored at 520 nm, the absorption maximum of [Fe(bipy)3]2+.. The protein concentrations were 3.3 μM and 6.7 μM for MoFeP and FeP, respectively.

ATP activation

The assay solutions contained 0.4 μM MoFeP and 1.6 μM FeP. In the assays where the concentration of MgATP is varied, the MgCl2 concentration was 5 mM, and the ATP concentration was adjusted by addition of ATP from a 500 mM Na2ATP stock. The concentration of MgATP was calculated using [MgATP]/([Mg2+][ATP]) = 5.01 × 104 M−1.62

ATP hydrolysis/e- ratio measurements

ATP was measured as released inorganic phosphate by the formation of a phosphomolybdate complex.63 Productive electrons transferred were determined from the amount of C2H4 produced. The MoFeP concentrations for the 4:1, 1:1 and 1:10 MoFeP/FeP ratio measurements were 4 μM, 1 μM and 0.4 μM, respectively.

AlF4− inhibition

AlF4− inhibition experiments were carried out under standard turnover conditions, but at pH 7.3. The protein concentrations were 0.4 μM MoFeP and 1.6 μM FeP. The NaF concentration was 5 mM and the AlCl3 concentration was 0.25 mM.63 A slow inhibition model was used to fit the data: v = (v0(1 − e−kx))/k, where v0 is the initial rate and k is the rate of inhibition.47

Dilution effect measurements

Dilution experiments were carried out under standard turnover conditions, with the exception that the assay duration was 15 min. The MoFeP and FeP component ratio was held at 1:4, where the MoFeP concentration was varied from 0 to 0.5 μM. The robustness of the regeneration solution at high protein concentrations was verified, since C2H4 production scaled linearly with time up to 30 min.

Thorneley-Lowe simulations

WT-MoFeP and βK400E-MoFeP dilution and turnover experiments were simulated using the Thorneley-Lowe model for C2H2 reduction to determine if changes in the rate of association, k1, could model the different activities of WT-MoFeP and βK400E-MoFeP. C2H4 formation was simulated by numerically solving the Thorneley-Lowe scheme using the Mathematica script included in the Supporting Information.32 The numerical solution to the Thorneley-Lowe scheme yielded the concentration of all reaction intermediates and products, including C2H4. Although most rate constants used were determined for Kp-nitrogenase (Table S3), these values are generally also appropriate for simulating Av-nitrogenase kinetics.64,65 When available, rates were used for Av-nitrogenase, with the exception of k−3, which was adjusted to account for the higher activity of Av-nitrogenase compared to Kp-nitrogenase, as described previously.65 The simulation that best describes the data was determined using a manual grid search, where k1 was varied in small intervals (Figure S8). In simulating turnover experiments, all rate constants are held equal between βK400E-MoFeP and WT-MoFeP, except for the respective values of k1, which were obtained previously from dilution experiment simulations.

Crystallography and data collection

βK400E-MoFeP crystals were grown using the sitting drop method. A 2 μL solution of 215 μM (50 mg/mL) βK400E-MoFeP in a buffered solution of 50 mM Tris, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl was mixed with 2 μL of well solution in the drops. Crystals were grown against 0.25 mL well solution (18% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 10,000, 600 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 5 mM Na2S2O4). Crystals were cryo-protected by soaking them in well solution containing 20% PEG 400. X-ray diffraction data were collected at SSRL beamline 12–2 at a wavelength of 0.98 Å. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with 1M1N as search model using phenix.MR. The structure was refined by automated refinement using phenix.refine66 and manual refinement using coot.67 Images were made in Pymol (Delano Scientific).68 Final data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Anderson for assisting us in optimizing procedures for the precise measurement of ethylene and phosphate, Dr. Thomas Spatzal for providing assistance during the crystallographic refinement, Drs. P. Wilson and G. Watt for providing the Mathematica script for Thorneley-Lowe simulations. We also acknowledge J. Wagner for assistance in analyzing amino acid conservation in nitrogenase and Dr. Y. Suzuki for critically reading the manuscript and insightful discussion. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM099813 to F.A.T.). C.P.O. was additionally supported by a USDA NIFA fellowship (Grant 2015-67012-22895). F.A.T. acknowledges the Frasch Foundation for additional support (Grant 735-HF12).

Footnotes

Sequencing of genomic A. vinelandii DNA for all mutants, growth curves for all Av mutants, electron density maps around residue 400 for βK400E-MoFeP, and crystal packing comparison between βK400E-MoFeP and WT-MoFeP, EDC crosslinking gels for all mutants and WT-nitrogenase and βK400E-nitrogeanse in presence of nucleotides, C2H2 as a function of FeP concentration for all mutants, chelation experiment controls, simulations of the dilution effect, detailed schemes for the nitrogenase FeP and MoFeP cycles, Mathematica script for Thorneley-Lowe simulations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ubbink M. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1060. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreiber G, Haran G, Zhou HX. Chem Rev. 2009;109:839. doi: 10.1021/cr800373w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelletier H, Kraut J. Science. 1992;258:1749. doi: 10.1126/science.1334573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schindelin H, Kisker C, Schlessman JL, Howard JB, Rees DC. Nature. 1997;387:370. doi: 10.1038/387370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang C, Iwahara J, Clore GM. Nature. 2006;444:383. doi: 10.1038/nature05201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubbink M. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:415. doi: 10.1042/BST20110698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashir Q, Volkov AN, Ullmann GM, Ubbink M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:241. doi: 10.1021/ja9064574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jasion VS, Doukov T, Pineda SH, Li H, Poulos TL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213295109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nocek JM, Knutson AK, Xiong P, Co NP, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6165. doi: 10.1021/ja100499j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong P, Nocek JM, Vura-Weis J, Lockard JV, Wasielewski MR, Hoffman BM. Science. 2010;330:1075. doi: 10.1126/science.1197054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scanu S, Foerster JM, Ullmann GM, Ubbink M. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:7681. doi: 10.1021/ja4015452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulsker R, Baranova MV, Bullerjahn GS, Ubbink M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1985. doi: 10.1021/ja077453p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin L, Kostić NM. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6073. doi: 10.1021/bi00074a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rees DC, Akif Tezcan F, Haynes CA, Walton MY, Andrade S, Einsle O, Howard JB. Philosophical Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2005;363:971. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tezcan FA, Kaiser JT, Mustafi D, Walton MY, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2005;309:1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1115653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tezcan FA, Kaiser JT, Howard JB, Rees DC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:146. doi: 10.1021/ja511945e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danyal K, Mayweather D, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6894. doi: 10.1021/ja101737f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzilotta WN, Parker VD, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:399. doi: 10.1021/bi971681m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth LE, Nguyen JC, Tezcan FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13672. doi: 10.1021/ja1071866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth LE, Tezcan FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8416. doi: 10.1021/ja303265m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danyal K, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9255. doi: 10.1021/bi201003a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duval S, Danyal K, Shaw S, Lytle AK, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Antony E, Seefeldt LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles CJ, Smith L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;197:152. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(70)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cordewener J, Krüse-Wolters M, Wassink H, Haaker H, Veeger C. Eur J Biochem. 1988;172:739. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willing AH, Georgiadis MM, Rees DC, Howard JB. J Biol Chem. 1989;265:6596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willing A, Howard JB. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid B, Einsle O, Chiu HJ, Willing A, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15557. doi: 10.1021/bi026642b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard JB, Rees DC. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2965. doi: 10.1021/cr9500545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe DJ, Thorneley RN. Biochem J. 1984;224:877. doi: 10.1042/bj2240877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorneley RN, Lowe DJ. Biochem J. 1983;215:393. doi: 10.1042/bj2150393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson PE, Nyborg AC, Watt GD. Biophys Chem. 2001;91:281. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glick BR, Brooks HE, Pasternak JJ. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:276. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.276-279.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgess BK, Jacobs DB, Stiefel EI. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;614:196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(80)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SLA, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2002;297:1696. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deits TL, Howard JB. 1990;265:3859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolle D, Kim C, Dean D, Howard JB. 1992;267:3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seefeldt LC. Protein Sci. 1994;3:2073. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NaCl inhibits nitrogenase by affecting both electrostatic FeP-MoFeP interactions and reducing the Kd of FeP for ATP. Despite the dual modes of inhibition, this experiment is a useful diagnostic to compare relative binding affinities between FeP and MoFeP mutants, as we do for WT-MoFeP and βK400E–MoFeP.

- 40.Deits TL, Howard JB. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanzilotta WN, Ryle MJ, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10713. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.As reported by Howard and colleagues, chelation by bipy is actually more complex than a first-order reaction and is better described by bi-exponential kinetics, which has been ascribed to different conformational states of FeP. For the purposes of our experiments, we deem apparent first-order rate constants sufficient to describe the observed effects.

- 43.Christiansen J, Chan JM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;80:195. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim CH, Newton WE, Dean DR. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2798. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Renner KA, Howard JB. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5353. doi: 10.1021/bi960441o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duyvis MG, Wassink H, Haaker H. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morrison JF. Trends Biochem Sci. 1982;7:102. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorneley RN. Biochem J. 1975;145:391. doi: 10.1042/bj1450391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe DJ, Fisher K, Thorneley RN. Biochem J. 1990;272 doi: 10.1042/bj2720621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thorneley RN, Lowe DJ. Biochem J. 1984;224:903. doi: 10.1042/bj2240903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hope AB. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1456:5. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sydor JR, Engelhard M, Wittinghofer A, Goody RS, Herrmann C. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14292. doi: 10.1021/bi980764f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiel C, Selzer T, Shaul Y, Schreiber G, Herrmann C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401160101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schreiber G. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:41. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schreiber G, Fersht AR. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5145. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clore GM, Tang C, Iwahara J. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:603. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Howard JB, Kechris KJ, Rees DC, Glazer AN. PloS one. 2013;8:e72751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kozakov D, Li K, Hall DR, Beglov D, Zheng J, Vakili P, Schueler-Furman O, Paschalidis IC, Clore GM, Vajda S. Elife. 2014;3:e01370. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacobs D, Mitchell D, Watt GD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:317. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klugkist J, Haaker H, Wassink H, Veeger C. Eur J Biochem. 1985;146:509. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos Dos PC. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;766:81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-194-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pecoraro VL, Hermes JD, Cleland WW. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5262. doi: 10.1021/bi00317a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fiske CH, Subbarow Y. J Biol Chem. 1925;66:375. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duyvis MG, Wassink H, Haaker H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fisher K, Newton WE, Lowe DJ. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3333. doi: 10.1021/bi0012686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Delano WL. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.