Abstract

Significance

Lethal fetal diagnoses are made in 2% of all pregnancies. The pregnancy experience is certainly changed for the parents who choose to continue the pregnancy with a known fetal diagnosis but little is known about how the psychological and developmental processes are altered.

Methods

This longitudinal phenomenological study of 16 mothers and 14 fathers/partners sought to learn the experiences and developmental needs of parents who continue their pregnancy despite the lethal diagnosis. The study was guided by Merleau-Ponty's philosophic view of embodiment. Interviews (N = 90) were conducted with mothers and fathers over time, from mid-pregnancy until 2–3 months post birth. Data analysis was iterative, through a minimum of two cycles of coding, theme identification, within- and cross-case analysis, and the writing of results.

Results

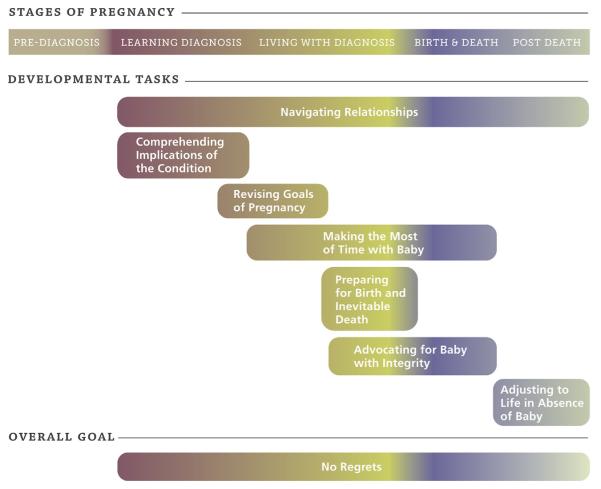

Despite individual differences, parents were quite consistent in sharing that their overall goal was to “Have no regrets” when all was said and done. Five stages of pregnancy were identified: Pre-diagnosis, Learning Diagnosis, Living with Diagnosis, Birth & Death, and Post Death. Developmental tasks of pregnancy that emerged were 1) Navigating Relationships, 2) Comprehending Implication of the Condition, 3) Revising Goals of Pregnancy, 4) Making the Most of Time with Baby, 5) Preparing for Birth and Inevitable Death, 6) Advocating for Baby with Integrity, and 7) Adjusting to Life in Absence of Baby. Prognostic certainty was found to be highly influential in parents' progression through developmental tasks.

Conclusion

The framework of parents' pregnancy experiences with lethal fetal diagnosis that emerged can serve as a useful guide for providers who care for families, especially in perinatal palliative care. Providing patient-centered care that is matched to the stage and developmental tasks of these families may lead to improved care and greater parent satisfaction.

Keywords: USA, Phenomenology, Longitudinal, Prenatal diagnosis, Pregnancy, Developmental task, Lethal fetal diagnosis, Perinatal palliative care

The majority of couples embark upon pregnancy, assuming that they will have a healthy child. Parents expect prenatal tests to confirm that everything is going normally with their pregnancy. Hence, those who are told of a lethal fetal diagnosis (LFD) experience intense grief and shock when their expectations are shattered (Côté-Arsenault and Denney-Koelsch, 2011; Lalor et al., 2009; Sandelowski and Barroso, 2005). In 3% of fetuses, conditions exist that are life-limiting and 2% are considered lethal (Coleman, 2015). Under these circumstances, 20–60% of parents choose not to intervene, and continue their pregnancies (Breeze et al., 2007; Leuthner and Jones, 2007; Walker et al., 2008). Factors influencing parent choices include their views on abortion, prognostic certainty of fetal condition, concern for what is best for the affected baby, and personal choices of the effect on one's family and relationships having an impaired child to care for (Sandelowski and Barroso, 2005). This study focused on those parents who continued their pregnancies with a LFD.

1. Conceptual framework: pregnancy as a developmental process

Viewing pregnancy as a developmental process provides a normative approach to an anticipated human development event. A developmental task is a psychosocial process that is undertaken to continue growth or change, sometimes undertaken simultaneously or, more often, the completion of one makes way for another to begin. Developmental theories, such as those of cognition or learning, vary in their assumptions regarding whether stages or tasks are discontinuous or continuous, and whether everyone goes through them in exactly the same way (i.e. multifinality) (Cicchetti and Rogosch, 1996; Kail and Cavanaugh, 2010). While pregnancy developmental theories are not as refined as child developmental theories they can serve as a general guide to care providers to assess parent's focus and motivations across pregnancy and parenting. In the instance of pregnancy the developmental tasks move an individual as they move from not-parent to parent-to-this-child.

As many scholars have noted, pregnancy is a time to prepare for parenthood for both mothers and fathers. Mothers undergo physical, psychological and social processes to achieve their maternal identity (Flagler and Nicoll, 1990; Nelson, 2003; Rubin, 1976, 1984).Rubin (1984) described four tasks in pregnancy to achieve maternal identity 1) ensuring safe passage for mother and child, 2) ensuring acceptance of the child, 3) binding-in, and 4) giving of oneself. Less is known about fathers' development during pregnancy, but they appear to undergo a similar psychological and emotional transition (Valentine, 1982). In a meta-synthesis of 13 studies, Kowlessar et al. (2015) found that fathers' experiences moved from feeling distant from the pregnancy in the first trimester, to reaching acceptance and becoming emotionally invested in the second trimester, when they can feel the baby move. In the third trimester, fathers redefined themselves as a father and left their old self behind (Kowlessar et al., 2015). It is clear that pregnancy is life-changing for both mothers and fathers.

In the situation of a LFD, the developmental processes of pregnancy are likely changed when it is known that there will be no healthy baby to parent. O'Leary (2009) identified revised tasks in pregnancy subsequent to perinatal loss due to the parents' grief and fear of another perinatal loss. While no literature was found that specifically addressed altered tasks of pregnancy in the case of LFD there is evidence that the social aspects of pregnancy are altered after a fetal diagnosis. Sandelowski and Barroso noted that women with a prenatal diagnosis sought “stigma management” when they experienced fear of what others may think of them post diagnosis (2005, p. 315). In the prior work of the authors of this current study and that of others, parents reported feeling “utterly alone” and disconnected from family and friends after sharing their baby's diagnosis (Côté-Arsenault and Denney-Koelsch, 2011, p. 5) and mothers have said that they feel like public property surrounded by expectations of a healthy baby (Smith et al., 2013). Because a pregnancy removes usual social barriers in public places, all of these mothers reported that their social interactions were often awkward and isolating.

Prenatal attachment, or binding-in to baby, is a complex process under the most routine circumstances (Rubin, 1984). Parental withholding of emotional attachment has been noted in some pregnancies when the future with the baby was uncertain (Côté-Arsenault and Donato, 2011; Rothman, 1986; Laxton-Kane and Slade, 2002). Our prior work has shown that parents felt attached to their babies with LFD, valued them as a person, and took measures to care for themselves in an effort to improve fetal outcomes (Côté-Arsenault and Denney-Koelsch, 2011; Côté-Arsenault et al., 2015).

2. Pregnancy loss

Pregnancy loss, at any gestation or in the neonatal period, is known to cause intense grief for many from a deep sense of loss for a wished-for child but also for one's sense of self, their role as a parent, their ability to be a biological woman, and a sense of safety in the world (Côté-Arsenault, 2011; Côté-Arsenault and Mahlangu, 1999; Garstang et al., 2014; Hill et al., 2008). Prior pregnancy loss may also negatively impact subsequent pregnancy experiences, parenting, and child outcomes due to fear of another loss, anxiety during pregnancy and hypervigilance of living children (Blackmore et al., 2011; Côté-Arsenault, 2007; O'Leary and Warland, 2012; Theut et al., 1992).

2.1. Fetal diagnosis

A fetal diagnosis infers that the fetus has a condition, syndrome, or abnormality that is pathological. Life-limiting fetal diagnosis implies that the condition will shorten the life of the baby; lethal fetal diagnosis is defined here as a condition will lead to death at any time up to 2–3 months after birth.

Amidst the grief and anticipated loss with a LFD, parents can also experience some positive outcomes. Personal growth after LFD was identified in 18 out of 25 parents by Black and Sandelowski (2010). Lalor, Begley and Galavan also found that women had “recasted hope” as a result of their coping and adaptation to fetal diagnoses (2008, p. 462). Lalor and colleagues (Lalor et al., 2009) described women's adaptation to fetal diagnosis in the Republic of Ireland, where termination of pregnancy is not legal. Their resulting theory depicts, across the women's pregnancy experiences, their pre-ultrasound Assume Normal stance of their pregnancy through the Shock, Gaining Meaning, and Rebuilding processes of coping and decision-making regarding continuing or terminating the pregnancy. Two different information seeking styles—high information seekers and information avoiders— were also identified (Lalor et al., 2008) suggesting that care providers should match their approach to women's preferred style.

Beyond the prospective research of Lalor and team (2008; 2009), the body of knowledge of parent experiences of continuing pregnancy with a known life limiting fetal diagnosis is sparse. A limited number of studies focused on a single fetal diagnosis, and others provided retrospective accounts. Two additional prospective studies described parents as being shocked, finding the pregnancy intensely difficult, but nonetheless, loving their baby as a person (Côté-Arsenault and Denney-Koelsch, 2011; Smith et al., 2012).

Normal pregnancy is a time-limited, nine month gestational process, often divided into three 13 week trimesters, or more recently, as 40 weeks of gestation for fetal development (Jorgensen, 2010). However, Sandelowski and Barroso (2005) describe pregnancies as being experienced as two halves since the advent of routine prenatal testing: pre- and post-testing. Indeed, the issue of the marking of time in pregnancy is a common finding in the studies on response to fetal diagnosis. Smith, Dietsch, and Bonner (2012) reported that time was distorted for parents who continued their pregnancy with a serious or lethal fetal diagnosis as they took in the reality of their baby's diagnosis and mindfully enjoyed their time with baby. Across all prospective studies the dimensions of the pregnancy experience varied from being a process of adaptation, or an experience of time distortion. Seeking to make sense of time during pregnancy seems to be inherent in the experience.

All studies indicate that learning of a life-limiting fetal diagnosis dramatically changes the experience of pregnancy (Côté-Arsenault and Denney-Koelsch, 2011; Lalor et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2012). Notable gaps in the literature include father's perspective and details of the developmental process after choosing to continue the pregnancy. This study was designed to address both of these gaps. Therefore, the broad purpose of this investigation was to prospectively describe parents' lived experience of continuing pregnancy with a lethal fetal diagnosis (LFD). Within this broad goal was a secondary aim to investigate the developmental tasks of pregnancy that parents undertake after receiving a lethal diagnosis and continuing the pregnancy.

3. Methods

This is a longitudinal, hermeneutic phenomenological study of continuing pregnancy with a LFD that is informed by the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty (1945/2005) who recognized that experience in the world comes through our embodiment in the world. Merleau-Ponty identified four aspects of human's lifeworlds or dimensions of experience that are consistent with aspects of pregnancy, i.e. time (temporality), body (corporeality), relationships (relationality) and space (spatiality). Merleau-Ponty espoused that we perceive the world through who we are, in relationship with others, and therefore researchers cannot bracket themselves nor their prior knowledge when viewing the life experiences of others. His philosophy provides a lens through which the authors, a nurse and a physician, could seek to understand the experience of the parents in this study.

3.1. Recruitment

Potential participants were identified by their various care providers. They were English-speaking women who were 18 years or older, with a singleton pregnancy, and had decided to continue their pregnancy after learning of a lethal fetal diagnosis (defined here as estimated neonatal prognosis of 2 months or less).

Individuals were referred to the study with maternal permission. The Principal Investigator (PI) then called each mother to explain the study and purposively screen them for study appropriateness. Pregnant mothers asked their spouse or partner if they wanted to participate; lack of partner participation did not preclude maternal inclusion. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all involved institutions. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

3.2. Sample

Sixteen mothers, 13 fathers and 1 female partner enrolled in the study from 4 states (mid-Atlantic and mid-Western USA). Participants received care at a variety of institutions, ranging from large university hospitals to community hospitals. First interviews were conducted between 20 and 35 weeks gestation. Fifteen mothers and 12 spouses/partners completed the study with 2–5 interviews each. One couple and two fathers chose not to participate further after the first interview, resulting in a total of 90 interviews; 45 prenatal and 45 postnatal. Demographics, obstetrical history, and fetal diagnoses are displayed in Tables 1–3. The parents were certain about the prognosis of lethality for 13 of the 16 babies. Six babies were stillborn and five died shortly after birth. Three babies lived for 1–9 weeks. Two babies who had severe oligohydramnios, were alive and expected to survive at the end of this study.

Table 1.

Demographics of sample.

| Mothers N = 16 | Fathers/Partners N = 13/1 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Range M(SD) | 22–42 32.9 (5.5) | 21–49 33.64 (7.2) |

| Race N(%) | ||

| Caucasian | 11 (68.8%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| African-American | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (6.3%) | – |

| Education in years | ||

| Range M(SD) | 12–21 15.1 (2.8) | 10–19 13.9 (2.9) |

| Family Income | ||

| Range (median) | 0 - >120,000 | ($60–80,000) |

| Relationship status N(%) | ||

| Married | 11 (68.8%) | |

| Single (not living together) | 3 (18.8%) | |

| Partnered (living together) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| Occupation N(%) | ||

| Professional | 5 (31.3%) | – |

| Paraprofessional | 2 (12.5%) | 5 (31.3%) |

| Home | 6 (37.5%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Service Worker | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Unskilled labor | 1 (6.3%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Student | 1 (6.3%) | – |

| N/A | – | 2 (12.5%) |

| Religiosity/spirituality N(%) | ||

| Not at all | - | 2 (14.3%) |

| Somewhat | 12 (75%) | 8 (57.1%) |

| Extremely | 4 (25%) | 4 (25%) |

| Religion affiliation N(%) | ||

| Christian | 12 (75%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| Muslim | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Other | 1 (6.3%)* | – |

| None | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (18.8%) |

Table 3.

Fetal diagnoses (N = 16).

| Anencephaly | 1 |

| Ectopia cordis | 1 |

| Partial trisomy 5p | 1 |

| Severe oligohydramnios | 3 |

| Severe skeletal dysplasia | 1 |

| Tetrasomy 9p | 1 |

| Trisomy 13 | 4 |

| Trisomy 18 | 4 |

3.3. Data collection

Data were obtained through in-depth interviews, field notes, participant blogs, and member checks. Initial in-depth interviews took place as close to the time of fetal diagnosis as possible between Fall 2012 through Spring 2014. Couples were initially scheduled to be interviewed twice prenatally and twice after the birth/death of the baby. The PI conducted and digitally-recorded all the interviews either in person, by phone, or via video conference (Skype™), based on parent preference and geographic feasibility. She used an interview guide with broad, open-ended questions (see Table 4). Interviews ranged in length from 30 to 120 minutes; initial interviews were generally the longest. Participants were compensated with a small sum for their time and effort, and received a small gift at the first and last interviews.

Table 4.

Interview guide.

| Topic | Joint interview | Individual interviews |

|---|---|---|

| First Interview | ||

| Experiences |

|

|

| Needs (Developmental Tasks) |

|

|

| Subsequent Interviews | ||

|

|

Interviews were conducted with both parents initially, then separately with each parent whenever possible. One mother's follow-up interview after her baby's death was done in written form at her request to be emotionally easier for her; this method was approved by IRB. Blog posts from three were also incorporated into the data at the participants' request.

3.4. Data analysis

Data analysis co-occurred with data collection. Field notes were inserted into the transcripts which were professionally transcribed and carefully verified. De-identified transcripts were imported into Atlas.ti7 for data management. All team members (including research assistant) listened to each interview recording and read the transcript to begin data immersion and analysis. Data were analyzed in accordance with Merleau-Ponty's philosophy and utilizing methods of Miles et al. (2014). Analysis was iterative, through a minimum of two cycles of coding, theme identification, within-and cross-case analysis, and the writing of results. Within-case analysis coincided with the conduct and coding of each interview; case summaries were compiled for each couple. Memos were written whenever questions or patterns in the data were identified. Constant comparison of case-by-case chronology using discussion and matrices facilitated cross-case comparisons. Negative cases, contradictions, and examples of themes were sought throughout analysis. When repetition was heard in the interviews across pregnancy, data saturation of themes was achieved and data collection ended. Member checks were done during follow-up interviews, and two written member checks were done later to provide feedback about the on-going analysis.

4. Results

Parents, pregnant for an average of 15 weeks after a LFD, shared their stories which revealed several stages of time that influenced their developmental tasks of pregnancy (See Fig. 1). The color gradation in the figure indicates evolution of all dimensions of parents' experience over time and down through the stages, tasks, and overall goal. Pseudonyms are used to protect the anonymity of participants.

Fig. 1.

Stages, developmental tasks and goal of pregnancy with lethal fetal diagnosis.

4.1. Overall goal

Parents were shocked and grieved to learn that their baby had a lethal condition. In a state of crisis they grappled with what to do next. The families in this study received their health care in a variety of settings and interactions with providers playing a major role in the experiences. Some received comprehensive care through an established perinatal palliative care program, others had fragmented care that was emotionally exhausting and did not meet their needs.

Despite the variations in their individual situations, an overall goal of wanting to Have No Regrets emerged for all parents. They all wanted to avoid having regrets and hoped to feel they did the best they could for their baby, as described by Gary at 31 weeks:

It's time we start getting our focus back here because … like we're going to be upset with ourselves if we sit there saying, “Why didn't we do this earlier? Why?” That's the whole thing about regrets, that we ask later, “Why didn't we do this earlier on? Why didn't we think of this?

Another father, Isaiah, shared his thinking about their decision to go elsewhere for delivery of their son:

In the big picture, doing this … we can look back and we can say we did everything humanly possible for him, giving him every possible chance that we could for him to survive. Six months from now, if we lose him, that's a difference maker.

Not … taking a trip to [a different hospital], that would be a very heavy cross to bear forever.

When parents were prepared and felt that they made the best decisions, they described the best possible outcome as Having No Regrets.

5. Stages of pregnancy

Parents' descriptions of their experiences revealed five stages of pregnancy that occurred chronologically and differentiated time segments within their stories of their pregnancies: Pre-Diagnosis, Learning the Diagnosis, Living with the Diagnosis, Birth and Death, and Post Death (Fig. 1). These stages refer to the parents' experience of time, that is, where they were in their pregnancy in relationship to milestones (e.g. conception, diagnosis and birth). Due to the fact that pregnancy is time-limited, ending in fetal death or birth, the final stages were inherent in the nature of gestation, not determined solely by the parents' experience. In fact, analysis of data of the tasks of pregnancy stalled until the time dimension of the experience was recognized, indicating its integral part of the whole experience.

Parents referred to their Pre-Diagnosis stage as a time of joy and positive anticipation. One father described their initial excitement abruptly ending at their 20 week ultrasound using hand gestures to show the high and the low he experienced when “all of a sudden [the sonographer's] demeanor changing and realizing something is wrong, that drop in emotion. It's something I never ever want to go through again in my life because I was up there and I quickly just dropped over here …” Some parents were initially hopeful that the screening test was incorrect or the implications not serious. “I thought everything was going to be fine because he just seemed so healthy, you know.”

However, the suggestion of abnormality moved all parents quickly into the Learning the Diagnosis stage which involved seeking information about the suspected condition from care providers, the internet, and any other source they could find. This stage coincided with the developmental task of comprehending the implications of the condition, and varied in length, depending on the time it took to obtain a diagnosis, see specialists, obtain additional testing, and come to terms with what it all meant for their baby. Parents were asked to make decisions about further invasive testing, such as amniocentesis and were offered termination as one option. All of our participants chose to continue their pregnancy. Their reasons included “I do not believe in abortion,” belief that this was not their choice to make, and that all life is precious. Some were religiously motivated but many wanted what they felt was best for their baby, based on a “gut feeling,” or “being able to live with myself.” They all embraced their decision once it was made and never expressed wavering from their choice. Only one couple expressed anguish over their decision-making; however, once they decided to continue they said that it had always been the right choice for them.

Once they had some understanding of the condition and why it was lethal, most parents moved into the Living with the Diagnosis stage. Several parents described their realization of this change. Abigail described it as “I wanted to know what was next. You're still pregnant and still have this beautiful baby that you're expecting and now you have to know where to go from here.”

The Living with the Diagnosis stage included making decisions about where to receive prenatal care, wanting to enjoy the pregnancy knowing that their time with baby was limited, and trying to make the most of it. Midway through Living with the Diagnosis parents began to make plans for labor, delivery and post death; several wrote formal birth plans. Preterm birth cut time short for some couples and they never had time to formalize their decisions. The stage of Birth and Death occurred in the hospital for all participants. For some parents, this stage included hospitalization for complications, including preterm labor, whereas others had natural labor or chose scheduled induction or C-section. The stage also included the birth and death (or in the case of stillbirth, death preceded birth) of the baby, making memories, saying good-bye, and discharge home. For others, the babies went to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for a period of time, where life support was eventually withdrawn, and death took place. Three infants left the hospital. One died at home on hospice; the other two were alive at the end of the study, having had less severe conditions than predicted. The stage of Post Death included the mother's postpartum care, grief, funeral or memorial services, memory-making at home, and often a return to work.

5.1. Developmental tasks of pregnancy

The diagnosis of a LFD immediately changed the pregnancy from normal to high risk, as quickly as the flip of a switch. Parents had to adjust their thinking and many aspects of their lives to accommodate this unfathomable reality. Seven developmental tasks of pregnancy were identified (Refer to Fig. 1). In this circumstance the formerly anticipated tasks of keeping mother and baby safe and healthy, bringing baby into the social milieu, and planning for a life with baby were not possible. The psychosocial tasks of pregnancy were greatly altered.

5.1.1. Navigating Relationships

Because pregnancy is a social event, many family and friends knew about the pregnancy and felt free to ask about how things were going. That changed after the fetal diagnosis was known. Navigating Relationships refers to the on-going developmental task parents addressed regarding what to say, to whom to say it, and the best mode of communication. The social aspects of pregnancy were navigated across pregnancy and after birth and death in a variety of ways. One parent reported that “One of the hardest things throughout this journey has been breaking the news to people.” Parents intentionally expanded or restricted their social circles of interaction, depending on the situation and their own coping style. They found this navigation process “exhausting” because parents never knew how friends, fellow church-goers, neighbors, and others would respond to their pregnancy complications. Often parents communicated using social media, such as Facebook or email, so they could both share the news about their unborn baby's condition and request limited communication:

Part of the whole reason for us to send out the notice that we did to everybody is because we didn't want to keep rehashing the same story of what's going on and being brought down or crying about this every day.

A few couples never used social media or email. They spoke in person or on the telephone with very select individuals.

Relationships with friends and partners were sometimes strained or even ended due to the circumstances of these pregnancies. Aisha shared such an instance:

I only have two people, and I don't consider them friends anymore, that when I first told them … they had a negative reaction … You go your way and I go mine and we'll just leave it like that.

Mothers had to share news with essential people at work as the pregnancy became obvious. “Yes … I sent it to everybody's email … I didn't want to just be bombarded with all the questions.” Most shared with very select friends and family to obtain more support. Fathers generally wanted to keep the pregnancy concerns private, keeping work and home separate.

Mothers recognized that social encounters after the birth could be difficult at places such as church and the grocery store. They wanted to let acquaintances know what was happening with the baby: “Because, you know when you're pregnant and after you had the baby, everybody is always asking, “Where's the baby? How's the baby doing?” Those are not questions that I want to have to answer.”

Navigating relationships also included the couple relationship. All committed couples (married or engaged) remained together throughout the study period. Several couples described being stronger after the experience, that they were sensitive to each other's needs, and made joint decisions that drew them together. When the couple relationships were less committed, the mothers did not feel consistent support. In fact, one mother said that she had cut the baby's father out of her life because he would not honor their baby with her anomalies.

During the hospitalization, parents wanted to include a small select group of family and friends in the hospital. All who had other children gave careful thought to the impact of the birth and death on their other children, and tried to find a balance between inclusion and protection.

All treasured their photographs and keepsakes of the LFD baby, many sharing photos as birth announcements. Many felt proud of their baby and were unafraid to share his or her memory. Abigail and Thomas were very private during the pregnancy and were surprised by their desire to share and tell stories with many people after their daughter's death.

Now, I feel like I flip flopped. I went from being very private to like singing it to the rooftops like, ‘Who wants to see my photos? Let me just tell you the whole day.’ I've really sparsed down how much I share sometimes because it does, it opens up a lot of emotions.

5.1.2. Comprehending Implications of the condition

This second task describes the parents' drive for information during the Learning the Diagnosis stage. The extensive medical interactions and information-seeking was for the purpose of comprehending what the diagnosis truly meant for their baby. “What does this all mean?!” They needed to know if there was any chance that the doctors were wrong, whether they should hope for a miracle, or accept the inevitable and move forward knowing that their baby was going to die. Parents found that waiting for confirmation of abnormalities and a definitive diagnosis “was torture.”

This task was fairly straightforward in some circumstances: when the parents had a medical background, when providers offered clear explanations, and/or when the prognosis was certain. For others, the experience was more complex, especially when the prognosis for baby was medically uncertain or the parents questioned it. Many parents met with perinatal palliative care teams to help them to clarify their understanding, goals and wishes. Without full comprehension and acceptance of lethality, they were reluctant or unable to talk about plans beyond where they were, and they did not move psychologically to focusing on other developmental tasks. Sheila explained:

I didn't understand why, why do babies with this condition not survive? I did not understand, like if her heart is not in that bad shape, and if it's fluid in her brain, I know that's bad, but they can do things about that. I did not understand why can't she survive?

When initial results were unclear or the prognosis uncertain, parents were left feeling lost about how to proceed. Candice's fetal diagnosis of severe oligohydramnios made her son's prognosis uncertain:

I'm uncertain of what's going to happen because my medical professionals are uncertain …. I'm not coming up with that feeling. I'm simply mirroring theirs. I'm not hopeful. I'm not pessimistic. I am even, 100 percent even. They don't know what's going on. They don't how it's going to be. That's kind of where my position is.

5.1.3. Revising Goals of the pregnancy

When a lethal diagnosis was clear and parents understood its full implications, they had to rethink their goals for this pregnancy. With a lethal diagnosis, parents needed to grieve for the lost future with their fantasized perfect child, and try to accept the new reality. They needed to change their expectations.

Without working through this task, parents were emotionally anxious and trying to be hopeful, waiting to see how the pregnancy progressed and baby fared at birth. In our sample, each parent revised goals at varying rates of time, sometimes synchronously through much conversation. Other couples were asynchronous which caused some tension with their relationship and personal needs.

New goals included spending special time with the baby during the pregnancy, or wanting the baby to be born alive so they could hold her and look in her eyes, or so that he/she could be baptized. Others revised their hope to making the most out of what they were facing, embracing each day with baby. Thomas shared the place they reached:

We kind of have a motto, “Five minutes at a time,” but we do have a lot of comfort knowing that we're doing the right thing and we're going to get to see her and meet her. We just pray that she's with us for a short time and how she can feel our touch and hear our voice.

High risk pregnancy status and access to palliative care services altered prenatal care choices for many, requiring decisions about whether or not to change obstetricians or medical care centers. They weighed what was best for this baby and for mother's care against the needs of their other children and proximity to support persons. Melissa was disappointed that her regular obstetrician encouraged her to go more than an hour away to the medical center where they provide perinatal palliative care: “I still am [disappointed]. I actually kind of told him … He brought up, you know, reasons why it might be better for the baby: the NICU is there if we decide to go that route and of course, they have more experience.”

5.1.4. Making the Most of Time with baby

As goals and expectations evolved, parents began to recognize that the pregnancy was likely their only time with the baby. This was particularly true of the mothers but many fathers acknowledged the same realization. They wanted to make the most of time and thus they undertook the task of consciously valuing the time they had during pregnancy, when the baby was “with us.” Parents ascribed personality characteristics to their unborn such as “smiling” and “calm” and they all called the baby by name.

Parents found ways to cherish each moment and squeeze in things such as taking pregnancy photos and “taking” baby to new places while they could. Preterm delivery was common in our sample, and that shortened the time for treasuring the baby. These parents felt cheated of the extra time. “Neither one of us felt ready. We were not ready to do this.” Parents particularly treasured seeing him/her on the ultrasound screen and feeling the baby move. A mother remarked, “That's what keeps me going, to see her moving.” Another mother described her teenage son's reaction: “Seeing her on the ultrasound last week … and how happy that made him, but we was in there just laughing, having so much fun.” And another said, “I don't know that it really changes much, but I think it's really wonderful. This may be the only opportunity that we actually have to meet her in all her life.” The non-pregnant parent found particular value in going to ultrasounds. “It is nice especially for like me because I don't get to feel her every day. I don't have that bond and so to see her is huge for me because I need that.”

Some fathers went out of their way to spend more dedicated time with the baby during pregnancy, reading to her or watching football together. One father describes:

A couple of weeks ago, we decided we'd start reading a book each night before we go to bed, kind of like—we have our favorite children's books that our parents had kept … For me personally, I think that makes me feel more connected to Leah because they do say that they can hear you and things like that.

One surprising finding was that many couples felt that their baby's birth was joyful, even if the baby was stillborn or died shortly after birth. One mother: “I promise you, I was gloriously happy. I felt his angel glow or something.” Several described their baby as “perfect,” and enjoyed looking at all of the baby's features for family resemblance.

Making the most of time with baby also included all of the memory making that took place after the birth: taking photos of the baby and with family members, making foot and hand prints or molds, having the grandmothers bathe the baby, even sleeping with the baby. All of these activities were precious to every parent.

5.1.5. Preparing for Birth and Inevitable Death

As gestational age advanced, there was the need to shift focus to planning for labor and delivery, birth, intervention, and baby's death. Parents often made this developmental shift reluctantly knowing that the end of pregnancy also meant the end of their baby's life. Others decided to be more positive and focus on their upcoming opportunity to meet their baby for the first time. Decisions included where to deliver, the timing and mode of delivery, and how much to intervene for baby at birth. They had to balance maternal health risk with other goals, such as having a better chance of having the baby born alive. Finding the right balance was easier when they had well-informed care providers who knew their wishes. One couple expressed that they were pleased with their care, “I think he kind of prepped everybody.”

Those who had time to do so wrote a birth plan or were able to express their wishes in real time without formalized birth plans. A template of the issues that should be addressed was provided by an informed care provider. This opened up many emotional discussions between couples. Sheila was dreading the process: “I realized halfway through Friday that part of my misery was just thinking about having to do this birth plan on Saturday.” Her husband John added his perspective, “It raised a lot of questions, not that we haven't thought about it and hadn't talked about it, but I think it was finalizing it that was making it the most difficult.” Although difficult, most parents were grateful for guidance on aspects of the birth to consider.

Funeral planning was addressed by some couples and avoided by others. At 32 weeks Gail and Timothy were not ready to deal with this: “We were going to do it … and neither of us took the time to make that call which, to me, was very telling that we're not ready to go there.”

By way of contrast, Jessica found planning the funeral to be a good way to cope, so at 27 weeks she shared:

Chris and I went to the funeral home already and we talked it over with them like what we need to do or what happens because we have never been a part of any planning any of these things before to know what would have to happen … It was weird … I didn't think that would be on my agenda until I was about 50 or so.

5.1.6. Advocating for Baby with Integrity

Parents advocated for their baby with care providers based on their values, beliefs, and sense of responsibility towards each other and their unborn child. They all had the conviction that their baby was a person of value, who should be treated with care and respect. It was their responsibility to do their best to insure the best care, avoiding pain and suffering whenever possible. They tried to separate out what was best for the baby from their desire to not let their baby go. Parents recognized that this was their responsibility because no one else would if they did not. Sheila was much relieved when she finally had a conversation with a neonatologist in the hospital before her C-section: “Somebody is looking out for my child. And doing everything he can to help … it didn't change anything about her prognosis. But it helped, it helped me.” They all did their best to make decisions about whether or not to perform resuscitation, and in some cases, when to stop.

After their baby died, parents wanted to keep the baby close by and comfortable. When it was time to let the body go, they wanted to make sure the body was in the care of trusted people. Parents usually asked a nurse that they knew and trusted to take the baby to the morgue. John was asked, with no forewarning, to place the baby in a body bag. “And I had to take her from Sheila and deliver her into this bassinette … And, um, it was the hardest thing for me.”

Another couple was given several options and they chose to be the last one to touch their baby's body. “She said that it’s really just the whole, being the last person to touch them thing. That really resonated with me because that's really how it felt.”

5.1.7. Adjusting to life in the Absence of baby

After the baby's death, parents grieved with tears, feelings of longing, and empty arms. As Sheila said in a postpartum interview, “I don't, I don't know. I just wanted to hold her again.” And John shared “I had the feeling I was going to have to go back to the funeral home and get her.” Sheila expanded: “I think I just, I realized I would never hold her again, ever.”

Parents also wanted to have as many memories of their short time with the baby after birth, whether stillborn or live born. They wanted the baby's life to be valued, honored, and remembered. Timothy was anticipating the funeral:

Tomorrow, I will see my little girl one last time, attend a service in her honor, and bury her. In some ways, I just want the day to be over. But in so many other ways, I don't want tomorrow to come at all.

Their final task also included integrating the memory of their baby into the rest of their life and that of their family. Many participants described a special place in the home such as a shelf for their baby's ashes; others added photos of their baby to their wall of family photos in a central location. Whether through photos, statues, gardens, or Christmas tree ornaments, all babies were recognized and memorialized.

Grieving and emotional healing took many forms. For the fathers, they all seemed to grieve deeply and quickly move on. For mothers it was not so easy. First, they experienced postpartum recovery including their milk coming in without having a baby to feed. Melissa pumped her milk and donated it as a way to give meaning to her son's life. Several mothers went for grief counseling. Many mothers returned to work where they were met with questions but also support. This task was not complete for most at the final interviews 8–10 weeks post birth.

Abigail gave her perspective in a post birth interview:

I mean I don't think we'll ever look back and say it was too hard, we wish we hadn't done it because even though we lost Leah, this has been the most miraculous time of our lives. I mean it was just—what we've learned, what we've gained, the love that we had, I mean we can't exchange that for anything.

Although a few mothers were deep in grief, having trouble functioning with daily activities, or felt regret about what had happened, the majority of couples were feeling positive about their experience and had no regrets about any of the decisions they had made.

6. Parent differences

Differences between the parents were examined throughout analysis. Mothers were generally talkative and open about their thoughts and feelings during joint and individual interviews although a couple of mothers had quiet personalities. Fathers (including the same sex parent who said that she was like a father) generally had more to say in an individual interview and always pointed out that they were not the one carrying the baby, therefore they had a different experience. Fathers stated that they were able to move away from the experience both physically and emotionally because they did not have the physical connection with the baby.

No major differences between the parents were found on goal, stages or developmental tasks. However, mothers' level of grief seemed to be higher at the end of the study than that of their partner. That said, most fathers were grief-stricken after the baby's death but they seemed to move away from acute grief more quickly.

7. Study trustworthiness

Numerous details of this study contributed to its trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Shenton, 2004). Consistent and meticulous measures were used during data collection to maximize dependability including the use of one interviewer, an interview guide, professional transcription, and team transcript verification. Individual coding and subsequent team analysis maximized data dependability and credibility.

The longitudinal research design with multiple interviews with nearly every participant provided prolonged engagement, and thus increased credibility. High retention of participants and inclusion of both parents contributed to our understanding of parent experiences. Member checks insured that we were interpreting the parents' words and meaning as accurately as possible. Negative case analysis was instrumental in our ability to decipher critical elements of the parent experiences most notably in elucidating the impact of prognostic uncertainty for three of the babies.

Transferability is not the primary goal of qualitative inquiry, but the sample in this study was varied in several areas that increased applicability to others. Participants were recruited from several states and from a variety of care providers, and there was a mix of primigravidas and multigravidas.

Lastly, consistent with the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty, the investigators brought their individual backgrounds to bear on this project which affected confirmability. The first author's background in childbearing family nursing, pregnancy theory, and qualitative research influenced the study focus. The second author, a physician with an active perinatal palliative care practice, was grounded in the care of families with chronic or life-limiting conditions.

8. Discussion

This study of the pregnancy experiences of 30 parents who continued their pregnancy with a known fetal diagnosis provides a framework for understanding the chronology and focus of the parents over time. The stages follow a logical sequence from before the diagnosis to after death, as suggested by Sandelowski and Barroso (2005) and Lalor et al. (2009) but provide details through the rest of the pregnancy that have not been reported previously. As suspected, parental psychosocial tasks were profoundly altered from those of a normal pregnancy (Rubin, 1984) but they still fall into the same dimensions of the pregnancy experience: physical care, social relationships, emotional attachment to the baby, and the giving of self. While some fathers' experiences were different from the mothers', the voices of both parents were heard for the first time and their tasks of pregnancy were one and the same. Consistent with Merleau-Ponty's lifeworlds, these tasks were achieved as they revised their goals and developed as a parent doing the best for their baby.

This work confirms the authors' previous work as well as that of Sandelowski and Barroso (2005) highlighting the challenge of managing social interactions in the setting of a complicated pregnancy. This remains one of the hardest tasks for parents to navigate.

Unlike Lalor and colleagues who reported two patterns of coping in their Irish study (2008), information-seeking and information-avoidance, all of the participants in this study actively sought information about their baby's condition. It is possible that the couples in this study were uniquely open in their thinking, and desire to participate in research so that some good would come out of their difficult situation. A new finding of this study is that parents continuing a pregnancy with a LFD have a common goal to Have No Regrets.

While perinatal palliative care consultation was not available for all, those who had access found it helped to clarify their baby's diagnosis and prognosis, and receive anticipatory guidance about what to expect. The couples who lacked prognostic certainty never revised their goals for the pregnancy, continuing to hope that the baby would survive. They too wanted to Have No Regrets so they Advocated for Baby with Integrity but did little or no birth planning because too much was unknown to allow planning. This finding suggests that prognostic certainty greatly impacts the parents' goals and motivations and thus their developmental trajectory for themselves as parents to this baby.

We were moved and surprised to find that the majority of parents were so happy to meet their baby, even joyful and at peace, even if he/she was stillborn or died within a few hours. No obvious pattern of parent characteristics, such as their religiosity, were associated with this response. In fact, only 12 of the 30 parents spoke specifically about their religious faith as impacting their pregnancy experience and decisions directly. The positive emotional experience, continuing to Make the Most of Time with Baby, contrasts sharply with the common experience of parents after a sudden, unexpected stillbirth when they are often in shock and have little or no time to prepare (Cacciatore et al., 2008). It appears that when parents know the prognosis ahead of time, they are able to adjust, treasure their time with their baby during pregnancy, and prepare emotionally for the birth and death (Côté-Arsenault et al., 2015). Rather than feeling a sudden and tragic loss, they can enjoy meeting their baby, feeling that they have done the best that they could.

Grief was apparent in both parents during the pregnancy and more acutely after the death of their baby. Our observation of higher levels of grief in the mothers than the fathers (and nonbiologic mother) corresponds with their likely higher levels of prenatal attachment than the non-pregnant parent. This finding is consistent with gender differences noted in the literature (Condon, 1985; Wallerstedt and Higgins, 1996). The emotional needs after loss are likely similar to those of other parents with perinatal loss (Badenhorst and Hughes, 2007; Côté-Arsenault, 2003; Koopmans et al., 2013).

A strength of the study is the inclusion of fathers who are rarely included in pregnancy research. Most fathers spoke profoundly about their experiences both during individual and joint interviews. While most parents found study participation helpful, this was especially true for fathers who said that they otherwise would not have talked to anyone besides their spouse about the experience. Participants found it therapeutic to share with someone (the PI) who was not part of their life and had no role in their care. A few couples stated that being interviewed helped them process their experience with each other, indicating that the joint interview provided an opportunity for communication between the parents. Further analysis of the father role within this sample is forthcoming.

8.1. Study limitations

Limitations of the study included a minimum of cultural diversity, in part because only English speaking participants were included. The religiosity of the parents was generally reported as “somewhat religious” but the impact of this designation is not truly known. The findings here are limited to singleton pregnancies, and to couples who chose to continue their pregnancy. Results of this study may not generalize beyond these parents; they self-selected to participate. Study beyond what was possible here is needed to examine the role of prognostic certainty for the parents and their desired care.

8.2. Clinical implications

Perinatal providers who are aware of the psychological journey travelled by parents living with a LFD are likely to be more sensitive to these parents' needs at different time periods. For example, if the parents are struggling to understand their baby's diagnosis and its implications, they may not be ready to hear from a provider about the need for a birth plan. Providers could help couples anticipate difficult social situations and include support persons whenever possible. Patient-centered care for these parents should include careful assessment of where they stand in their developmental tasks. These results provide an important perspective to inform obstetrics, neonatology, and perinatal palliative care. Perinatal palliative care teams should consider these stages and tasks of pregnancy as they offer comprehensive, psychosocial, multidisciplinary care over time. These results also highlight the importance of bereavement care to help parents to adjust to life without their baby.

Table 2.

Obstetrical history of mothers (N = 16).

| Number of pregnancies | ||

| Range M(SD) | 1–8 | 2.6 (2.0) |

| History of Infertility (N) | 3 | |

| History of miscarriages (N) | 3 | |

| Number of living children | ||

| Range M(SD) | 0–7 | 1.5 (1.9) |

| Number of adopted or step children | ||

| Range M(SD) | 1–3 | 0.6 (1.1) |

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R21 NR012733-01A1).

We thank LaPonda McKoy (Project Coordinator), Wendasha Jenkins (Research Assistant) and our consultants, Stephen Leuthner, MD and Karen Kavanaugh, RN, PhD. The figure artwork of our findings was done by graphic designer Renée Stevens.

References

- Badenhorst W, Hughes P. Psychological aspects of perinatal loss. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;21(2):249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B, Sandelowski M. Personal growth after severe fetal diagnosis. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2010;32(8):1011–1030. doi: 10.1177/0193945910371215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore ER, Côté-Arsenault D, Tang W, Glover V, Evans J, Golding J, O'Connor TG. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2011;198:373–378. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze AC, Lees CC, Kuman A, Missfelder-Lobos HH, Murdoch EM. Palliative care for prenatally diagnosed lethal fetal abnormality. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F56–F58. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.092122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore J, Radestad I, Froen JT. Effects of contact with stillborn babies on maternal anxiety and depression. Birth. 2008;35(4):313–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychology. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996;8(4):597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK. Diagnosis of fetal anomaly and the increased maternal psychological toll associated with pregnancy termination. Issues Law Med. 2015;30(1):3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JT. The parental-foetal relationship: a comparison of male and female expectant parents. J. Psychosomatic Obstet. Gynecol. 1985;4(4):271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D. Weaving babies lost in pregnancy into the fabric of the family. J. Fam. Nurs. 2003;9(1):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D. Threat appraisal, coping, and emotions in pregnancy after perinatal loss. Nurs. Res. 2007;56:108–116. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000263970.08878.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D. In: Loss and Grief in the Childbearing Period. Freda MC, editor. March of Dimes Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. My baby is a person”: parents' experiences with life-threatening fetal diagnosis. J. Palliat. Med. 2011;14(12):1302–1308. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, Mahlangu N. The impact of perinatal loss on the subsequent pregnancy and self: women's experiences. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1999;23:274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, Donato K. Emotional cushioning in pregnancy after perinatal loss. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2011;29(1):81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, Krowchuk H, Hall WJ, Denney-Koelsch E. We want what's best for our baby”: prenatal parenting of babies with lethal conditions. J. Prenat. Perinat. Psychol. Health. 2015;29(3):157–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagler S, Nicoll L. A framework for the psychological aspects of pregnancy. Perinat. Womens Health Nurs. 1990;1(3):267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garstang J, Griffiths F, Sidebotham P. What do bereaved parents want from professionals after the sudden death of their child: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-269. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PD, DeBackere K, Kavanaugh KL. The parental experience of pregnancy after loss. JOGNN J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(5):525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00275.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen AM. Born in the USA-The History of Neonatology in the United States: A Century of Caring. NICU Currents; Jun, 2010. www.anhi.org. [Google Scholar]

- Kale RV, Cavanaugh JC. Human Development: A Life-span View. fifth ed Wadsworth; Cengage Learning, Belmont, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans L, Wilson T, Cacciatore J, Flenady V. Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;(Issue 6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000452.pub3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000452.pub3, 2013. Art. No.: CD000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowlessar O, Fox JP, Wittkowski A. The pregnancy male: a metasynthesis of first-time fathers' experiences of pregnancy. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2015;33(2):106–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2014.970153. [Google Scholar]

- Lalor JG, Begley CM, Galavan E. A grounded theory study of information preference and coping styles following antenatal diagnosis of foetal abnormality. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;64(2):185–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04778.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor JG, Begley CM, Galavan E. Recasting hope: a process of adaptation following fetal anomaly diagnosis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;68:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.069. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxton-Kane M, Slade P. The role of maternal prenatal attachment in a woman's experience of pregnancy and implications for the process of care. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2002;20(4):253–266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0264683021000033174. [Google Scholar]

- Leuthner S, Jones EL. Fetal concerns program: a model for perinatal palliative care. MCN Am. J. Maternal Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):272–278. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000287996.90307.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M, Smith C. The Phenomenology of Perception. NY. Original work published; Routledge, New York: 1945/2005. 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. third ed Sage Publications; Los Angeles, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. Transition to motherhood. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(4):465–477. doi: 10.1177/0884217503255199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary J. Never a simple journey: pregnancy following loss. Bereave. Care. 2009;28(2):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary J, Warland J. Intentional parenting of children born after a perinatal loss. J. Loss Trauma. 2012;17(2):137–157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.595297. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman BK. The Tentative Pregnancy: Prenatal Diagnosis and the Future of Motherhood. Viking Penguin; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. Maternal tasks in pregnancy. J. Adv. Nurs. 1976;1(5):367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1976.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. Maternal Identity and the Maternal Experience. Springer; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. The travesty of choosing after positive prenatal diagnosis. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(3):307–318. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004;22:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SV, Dietsch E, Bonner A. Parents' experience of time distortion following diagnosis of a serious or lethal fetal diagnosis. Int. J. Childbirth. 2012;2(4) http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/2156-5287.2.4.212. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SV, Dietsch E, Bonner A. Pregnancy as public property: the experience of couples with a diagnosis of foetal anomaly. Women Birth. 2013;26:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theut SK, Moss HA, Zaslow MJ, Rabinovich BA, Levin L, Bartko JJ. Perinatal loss and maternal attitudes toward the subsequent child. Infant Ment. Health J. 1992;13(2):157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine DP. The experience of pregnancy: a developmental process. Fam. Relat. 1982;31:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Walker LV, Miller VJ, Dalton VK. The health-care experiences of families given the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 18. J. Perinatalo. 2008;28:12–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstedt C, Higgins P. Facilitating perinatal grieving between the mother and the father. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1996;25(5):389–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02442.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]