Abstract

The incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hyperlipidemia, with their associated risks of endstage liver and cardiovascular diseases, is increasing rapidly due to the prevalence of obesity. Although the mechanisms of NAFLD have been studied extensively, the underlying pathogenesis and the role of microRNAs in this process remain relatively unclear. MicroRNA (miRNA)-dependent posttranscriptional gene silencing is now recognized as a key element of lipid metabolism. Here we report that the expression of microRNA-24 (miR-24) is significantly increased in the livers of high-fat diet-treated mice and in isolated human hepatocytes incubated with fatty acid. Knockdown of miR-24 in those mice caused impaired hepatic lipid accumulation and reduced plasma triglycerides. Bioinformatic and in vitro and in vivo studies led us to identify insulin-induced gene 1 (Insig1), an inhibitor of lipogenesis, as a novel target of miR-24. Inhibition of endogenous miR-24 expression by way of miR-24 inhibitors led to up-regulation of Insig1, and subsequently decreased hepatic lipid accumulation. It is well established that liver-specific deletion of Insig1 leads to higher hepatic and plasma triglyceride levels by inhibiting the processing of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), transcription factors that activate lipid synthesis. As expected, miR-24 knockdown prevented SREBP processing, and subsequent expression of lipogenic genes. In contrast, the opposite result was observed with overexpression of miR-24, which enhanced SREBP processing. Thus, our study defines a potentially critical role for deregulated expression of miR-24 in the development of fatty liver by way of targeting of Insig1.

Conclusion

Our findings show a novel mechanism by which miR-24 promotes hepatic lipid accumulation and hyperlipidemia by repressing Insig1, and suggest the use of miR-24 inhibitor as a potential therapeutic agent for NAFLD and/or atherosclerosis.

The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the form of triglycerides, is increasing among people of all ages in proportion to the rapid rise in obesity and type II diabetes.1 In a large proportion of these patients, the condition progresses to fat-related steatohepatitis, known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which dramatically increases the risks of cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2 Cirrhosis due to NASH is an increasingly frequent reason for liver transplantation. It is estimated that 90% of obese patients have some form of fatty liver, ranging from simple steatosis to the more severe forms of NASH and cirrhosis.3

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is complex and is widely considered to be the hepatic expression of the metabolic syndrome, together with type II diabetes, insulin resistance, and obesity.4 In addition, oxidative stress and cytokines are important contributing factors, which together can result in steatosis and progressive liver damage in genetically susceptible individuals. The pathogenesis of NASH may be inherently involved with the metabolic syndrome and its associated insulin resistance and proinflammatory processes.5 For example, obesity is frequently linked to type-II diabetes and consequently, to hyperinsulinemia, which leads to increased insulin-like factor 1 (IGF-1) and elevated production of sex steroids and cytokines.1 In 2010, it was reported that obesity is associated with a chronic inflammatory state characterized by the release of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), two well-known inflammation-promoting cytokines.6 However, the cause(s) of NAFLD and the progression of NAFLD to NASH have yet to be defined.

The discovery of a class of naturally occurring small noncoding RNAs, termed microRNAs (miRNAs), over the last decade has provided new insight into the pathogenesis of NAFLD.7–10 A growing body of evidence suggests that aberrant expression of miRNAs is related to various human metabolic diseases and some miRNAs are key regulators of obesity-related fatty liver, type II diabetes, and atherosclerosis.8,11,12 Most notably, it is now well established that the introduction of specific miRNAs or anti-miRs into diseased cells and tissues can induce favorable therapeutic responses.13,14 The potential application of miRNA therapy is significant not only for cancer but also metabolic diseases, due to the apparent role of miRNAs as key regulators of lipid metabolism and tumorigenesis.

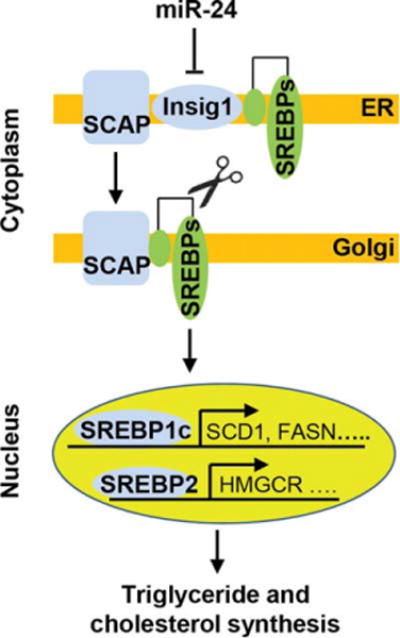

Our interest in miR-24 initially arose from hepatocyte-specific miRNA profiling studies in mouse livers, in which we showed that miR-24 is highly and specifically expressed in hepatocytes. Furthermore, we observed that a high-fat diet (HFD) significantly induced expression of miR-24 in livers of mice and identified Insig1 (insulin-induced protein 1) as a potential target gene of miR-24. Insig1 is a polytopic membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that regulates lipid synthesis by retaining SREBPs in the ER and preventing their proteolytic activation in the Golgi apparatus.15–17 The movement of SREBPs from ER to the Golgi complex is a central event in lipid homeostasis in animal cells.18–20 SREBPs are membrane-bound transcription factors that activate genes encoding enzymes required for synthesis of cholesterol and triglycerides.19,20 The three SREBP isoforms, SREBP1a, SREBP1c, and SREBP2, have different roles in lipid synthesis. SREBP1c is involved in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis, whereas SREBP2 is relatively specific to cholesterol synthesis.20 Immediately after their synthesis, SREBPs bind to SCAP (SREBP cleavage-activating protein). When Insig1 protein levels are low, SCAPs escort SREBPs to the Golgi, where they are processed and released into the cytosol, and can then enter the nucleus and activate transcription of lipogenic genes.19 Overexpression of Insig1 in liver inhibits lipogenesis and knockout of Insig1 leads to increased total content of both liver and plasma triglycerides,21,22 suggesting that the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 may play an important role in the development of NAFLD and hyperlipidemia.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatic Analysis

MiR-24 expression is elevated in livers of patients with NAFLD/NASH.23 To identify potential target genes of miR-24, we downloaded microarray raw data of normal and NAFLD/NASH patient liver samples from the PubMed GEO Database.24 mRNA profiles of five normal liver samples (male) and eight NAFLD/NASH liver samples (male) were compared using GeneSpring (Agilent Genomics). Differentially expressed genes were defined by a log-scale ratio ≤0.5 between paired samples with a P value <0.05. Based on these criteria, we identified 411 down-regulated genes in NAFLD/NASH samples (Supporting Table 1). To identify genes that have binding motifs of miR-24, we downloaded the target gene databases of miR-24 based on TargetScan,25 Pictar,26 and Starbase.27 These three databases were compared using Microsoft Access 2000, yielding 48 common potential targets that have miR-24 binding motifs (Supporting Table 2). We then compared the 411 down-regulated genes in livers of patients with NAFLD/NASH to 48 genes that have binding motifs for miR-24 using Microsoft Access 2010. Of the three genes that were overlapped between two databases, only Insig1 was related to hepatic lipid accumulation21,28,29 (Supporting Table 3).

Animals, Diet Treatment, and Sample Collection

Male Dicer1fl/fl mice on a mixed 129S4, C57Bl/6 strain background30 were crossed with C57Bl/6 Alb-Cre+/− mice31 to generate Dicer1fl/fl, Alb-Cre+/− mice. To specifically investigate the impact of miRNAs on mature liver function, we initiated Cre recombinase expression in 8- to 10-week-old mice. For this purpose, we used a double-stranded AAV vector that affords more rapid and efficient transgene expression than conventional AAV vectors by bypassing the need for conversion from a single-stranded to a double-stranded state after transduction.32 To restrict Cre expression to hepatocytes, we used a hepatocyte-specific transthyretin (Ttr) promoter and pseudotyped the vector genome with capsids from AAV8, a serotype that can transduce virtually all hepatocytes in vivo without causing toxicity.33 The AAV8-Ttr-Cre vector is highly efficient and can delete the floxed Dicer1 sequences in all hepatocytes within 48 hours.

Male C57Bl/6 mice (8 weeks old) were maintained on an HFD (Open Source D12492) for 8 weeks. The mice were then divided into two groups; one group was treated with miR-24-ASO (anti-sense oligonucleotide) and the other was treated with miR-24-MM-ASO (control scramble) for 4 weeks. At the 12th week, the mice were anesthetized and blood was collected by way of cardiac puncture. Subsequently, the livers were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

miR-24-ASO Injection

MiR-24-ASO (Exiqon) was formulated in 0.9% NaCl to a final concentration of 30 mg/mL. Eight-week-old male C57Bl/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) received a dose of 25 mg/kg miR-24-ASOor miR-24-MM-ASO (0.9% NaCl) weekly by way of tail vein injection.34 Mice were sacrificed at the indicated times. All procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the University of Minnesota, University of California San Francisco, and the Agency for Science Technology and Research, Singapore.

A more detailed description of Materials and Methods is included in the Supporting Information.

Results

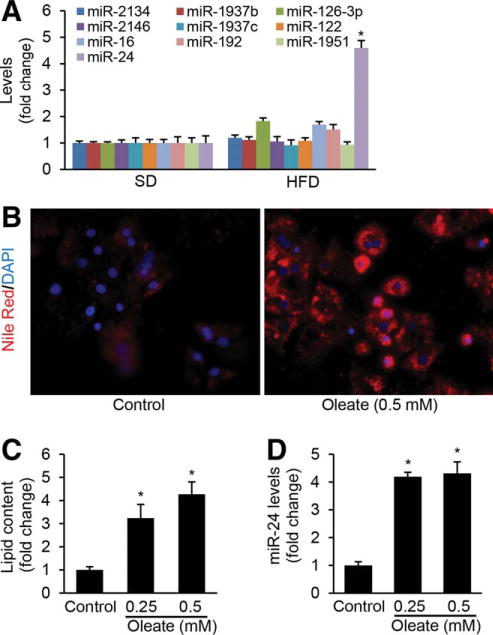

MiR-24 Is Robustly Induced in Fatty Acid Treated Human Hepatocytes, HepG2 Cells, and Livers of Mice on an HFD

Hepatocytes are the major cells that control lipid metabolism and the primary site of lipid accumulation in NAFLD. Since abundance is an important factor for cellular or physiological processes, we initially identified miRNAs that were highly and specifically expressed in hepatocytes. We therefore used hepatocyte-specific Dicer1 knockout mice to identify those miRNAs, allowing us to avoid expression changes of miRNA associated with hepatocyte isolations. Dicer1 is a cytoplasmic type-III RNase that plays a central role in miRNA biogenesis.7 To generate a global hepatocyte-specific miRNA deficiency mouse model, we disrupted miRNA processing in all hepatocytes of adult mice by knocking out Dicer1 using an AAV8-TTR-Cre system. We then performed miRNA profiling of livers from hepatocyte-specific Dicer1 knockout (DKO) and wild-type (WT) mice and considered miRNAs whose expression was at least 1.7-fold higher in WT than DKO mice as hepatocyte-specific miRNAs. This led us to identify at least 10 miRNAs that were the most highly and specifically expressed in hepatocytes, including miR-122, miR-192, and miR-24 (Table 1). To determine the potential roles of these abundant miRNAs in NAFLD, we fed WT C57Bl/6 mice an HFD (Supporting Fig. 1A–D) and measured their hepatic expression. Only miR-24 was up-regulated 4-fold in the livers of HFD-treated mice (Fig. 1A). In addition, miR-24 expression was 5-fold higher in hepatocytes versus nonhepatocytes (Table 1), indicating that liver parenchymal cells represent the main source of miR-24 expression. HFD dramatically induced expression of miR-24, suggesting its potential role in hepatic lipid accumulation.

Table 1.

Top Ten miRNAs That Are Highly and Specifically Expressed in Hepatocytes

| miRNA (mmu) | Average Ct (WT) | Average Ct (DKO) | Fold Change (Hc/non-Hc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-2134 | 17.618 | 18.109 | 3.92 |

| miR-1937b | 18.536 | 18.553 | 2.83 |

| miR-126-3p | 21.019 | 21.098 | 2.95 |

| miR-2146 | 21.214 | 21.671 | 3.84 |

| miR-1937c | 21.372 | 21.135 | 2.37 |

| miR-122 | 21.855 | 25.358 | 31.70 |

| miR-16 | 22.340 | 22.985 | 4.37 |

| miR-192 | 22.716 | 25.497 | 19.20 |

| miR-1951 | 23.028 | 22.362 | 1.76 |

| miR-24 | 23.061 | 23.934 | 5.12 |

To identify novel miRNAs that are highly and specifically expressed in hepatocytes, we performed hepatocyte-specific miRNA profiling from livers of hepatocyte-specific Dicer1 knockout and wild-type mice. MiRNAs that were >1.7-fold down-regulated in Dicer1 knockout mice and cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤24 were considered hepatocyte-specific miRNAs. Based on these criteria, we identified 10 miRNAs that are highly and specifically expressed in hepatocytes, including miR-122, miR-21, and miR-24. The expression of each mRNA relative to U6 nuclear small RNA (internal control) was determined using the 2−ΔCT method.

WT, wild type; DKO, Dicer1 knockout; Hc, hepatocyte. The Ct value of U6 small RNA (internal control) was 17.284 and 15.801 for WT and DKO mice, respectively.

Fig. 1.

miR-24 is highly induced in livers of HFD-treated mice and human hepatocytes treated with fatty acid. To identify the function of highly and specifically expressed miRNAs in hepatocytes in NAFLD, we determined the expression levels of the top 10 miRNAs in the livers of mice maintained on HFD for 2 months using Taqman microRNA Assay. (A) HFD treatment led to higher levels of miR-24 in livers of mice. (B,C) Oleate treatment increased lipid accumulation and (D) expression of miR-24 in primary human hepatocytes. The lipid content in the cultured hepatocytes was determined fluorimetrically using Nile Red, which has been shown to selectively stain intracellular lipid droplets. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

We also determined whether fatty acids can up-regulate the expression of miR-24 in primary human hepatocytes and hepatocyte-like cells in vitro. Oleic acids are the most abundant fatty unsaturated acids in liver triglycerides in both normal subjects and patients with NAFLD.35 In this study, both human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells were used for our in vitro models due to their increased sensitivity to fat accumulation and high levels of Insig1, SREBP1c, and SREBP2.35 Nile Red staining revealed that oleic acid treatment led to significantly higher levels of intracellular lipids in the primary hepatocytes (Fig. 1B,C), which further up-regulated expression of miR-24 (Fig. 1D). In HepG2 cells, oleate treatment displayed the same phenotype as visualized in human hepatocytes (Supporting Fig. 2A–C). Taken together, our in vivo and in vitro studies indicated that both HFD treatment in mice and fatty acid treatment in human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells can induce expression of miR-24.

MiRNAs exert their function by inhibiting the expression of target genes. To further elucidate the role of miR-24 in NAFLD, we began to identify target genes of miR-24 by combining messenger RNA (mRNA) profiling of human fatty livers with bioinformatic prediction of miR-24 binding motifs within potential target mRNAs. Due to high levels of miR-24 in fatty livers of humans,23 we initially identified down-regulated genes by comparing transcript profiles between five normal and eight human NAFLD/NASH liver samples. We identified 411 down-regulated genes in human fatty livers (Supporting Table 1). It is well established that the conserved seed region of miRNA that binds the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA is an important feature in the miRNA target recognition.26,36 Therefore, we further predicted genes that have miR-24 binding site using TargetScan,36 Pictar,26 and StarBase,27 and only selected overlapped hits from both Target and PicTar algorithms. This was confirmed by Ago HITS-CLIP (high-throughput sequencing of RNAs isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation; from Argonaute protein complex),27 which led us to identify 48 potential target genes that have binding motifs for miR-24 (Supporting Table 2).

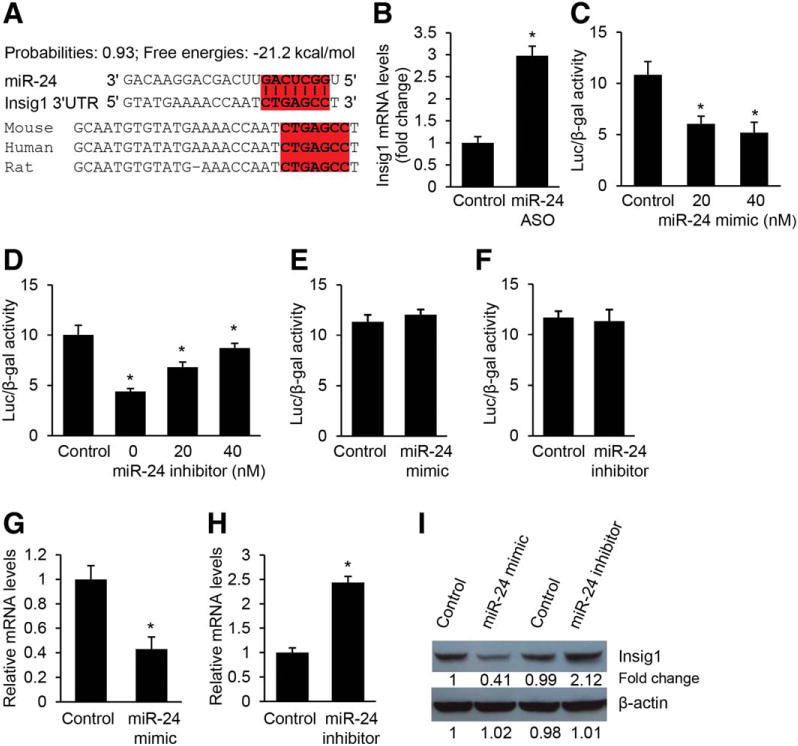

We then compared the 48 potential target genes with miR-24 binding sites to the 411 down-regulated genes in livers of human NAFLD/NASH patients. This led us to identify three genes including Insig1, KLF6 (Kruppel-like factor 6), and CXADR (Coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor) that have reduced expression in human fatty liver and a conserved binding motif for miR-24 (Supporting Table 3). It is well described that Insig1 is a potent inhibitor of lipogenesis by preventing SREBP processing.20,37 In addition, our prediction from in silico algorithms showed that the 3′ UTR of Insig1 mRNA was 100% complementary to the miR-24 5′ conserved seed region exhibiting the highest prediction score and binding energy (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we selected Insig1 as a potential target of miR-24.

Fig. 2.

Insig1 is a direct target of miR-24. (A) Bioinformatic prediction showing that the seed sequence of miR-24 has a high level of complementarity to Insig1 3′ UTR, prediction score, and favorable binding energy. Complementary sequences to the seed region of miR-24 within the 3′ UTRs of Insig1 are conserved between human, mouse, and rat and highlighted in red. (B) Knockdown of miR-24 in HFD-treated mice led to an increase in Insig1 mRNA levels. C57Bl/6 WT mice were kept on normal chow until 8 weeks of age and then maintained on HFD until 16 weeks of age. At that time, the mice were given miR-24-ASO (25 mg/kg, tail-vein injection) until 20 weeks. The C57Bl/6 mice maintained on HFD and treated with miR-24-MM-ASO served as control. The expression levels of miR-24 were determined by qRT-PCR. (C) miR-24 mimic transfection into Hepa1,6 cells caused dose-dependent inhibition of the activity of a luciferase reporter gene linked to the 3′ UTR of mouse Insig1. (D) Conversely, transfection with a miR-24 inhibitor antagonized the binding of miR-24 mimics to the 3′ UTR of mouse Insig1, which was reflected by increased luciferase activity. (E,F) Mutated binding motif for miR-24 within Insig1 3′ UTR impaired miR-24 binding, which is reflected by negligible change of luciferase activity after miR-24 overexpression or knockdown. (G) miR-24 mimic transfection into human hepatocytes inhibited expression levels of endogenous Insig1. (H) Knockdown of miR-24 by transfecting miR-24 inhibitor into hepatocytes caused an increase in endogenous Insig1 mRNA levels. (I) Western blot analysis further confirmed that miR-24 mimics repressed but miR-24 inhibitor induced protein levels of endogenous Insig1 in primary hepatocytes. The ImageJ program was used to quantify western blot bands. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Since Insig1 is a potential target of miR-24, we determined its expression by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in the livers of dietary obese mice treated with miR-24-ASO or miR-24-MM-ASO (control). It was not surprising that Insig1 expression increased 3-fold in the livers of miR-24-ASO-treated mice compared to those treated with scramble (Fig. 2B). Taken together, hepatic expression of miR-24 was increased in dietary mouse models of obesity, and the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 may play an important role in development of fatty liver.

Insig1 Is a Direct Target of miR-24

To establish that miR-24 directly recognizes the predicted target site within the 3′ UTR of Inisg1, the 3′ UTR region of Insig1 mRNA was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector (pMiR-Report) to generate pMiR-Insig1. Mouse hepatoma Hepa1,6 cells were transfected with pMiR-Insig1 and chemically synthesized miR-24 mimic or miR-24 inhibitor. Because cel-miR-67 has the lowest homology between mouse and human genomes, both the mimic and inhibitor designed based on cel-miR-67 were used as negative controls for miR-24 mimic or miR-24 inhibitor, respectively. We found that miR-24 mimic significantly down-regulated luciferase activity in a dose-dependent fashion compared to control mimics (Fig. 2C). Consistently, miR-24 inhibitor antagonized the inhibitory effect of miR-24 mimic on luciferase activity (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we mutated the binding motif for miR-24 within Insig1 3′ UTR, and found that both miR-24 mimics and inhibitors had no effect on luciferase activity (Fig. 2E,F), indicating a direct interaction between miR-24 and Insig1 mRNA. To further validate our prediction that Insig1 is a target of miR-24, we increased intracellular levels of miR-24 by transfecting miR-24 mimics into human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells in the absence of fatty acid. qRT-PCR and western blot revealed that miR-24 significantly inhibited expression of Insig1 in human hepatocytes (Fig. 2G,I) and HepG2 cells (Supporting Fig. 3A,C). In contrast, miR-24 knockdown by transfecting miR-24 inhibitor into both human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells led to an increase of mRNA and protein levels of Insig1 (Fig. 2H,I; Supporting Fig. 3B,C). These results confirmed that Insig1 is a direct target of miR-24.

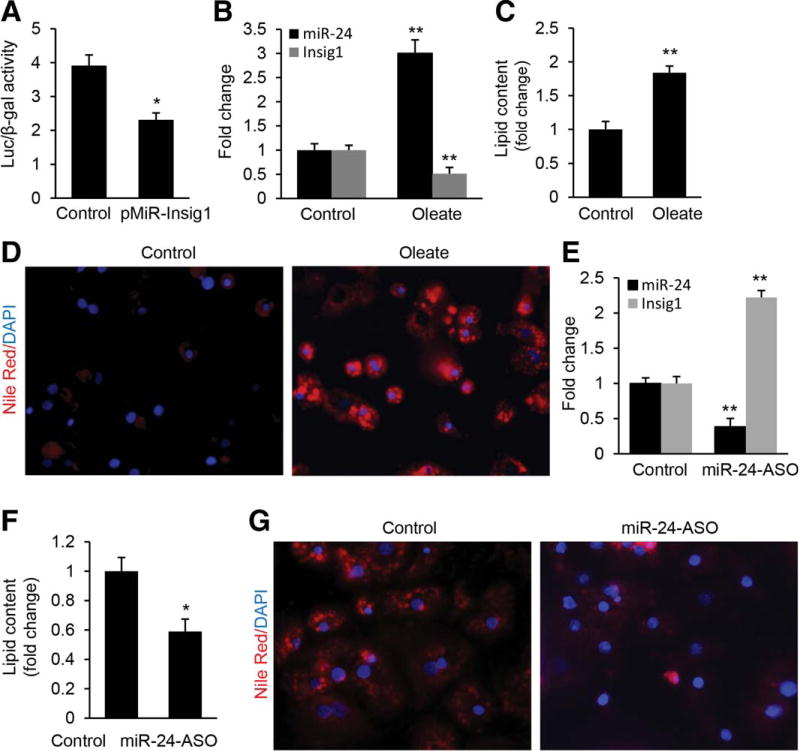

MiR-24 Directly Represses Expression of Insig1 During Lipid Accumulation in Primary Human Hepatocytes and HepG2 Cells

To investigate the role of the interaction between miR-24 and Insig1 in hepatic lipid accumulation, we mutated the binding motif of miR-24 within the 3′ UTR of Insig1 in the pMiR-Insig1 (referred to as pMiR-Insig1Mu), and introduced the luciferase reporter vector pMiR-Insig1 or pMiR-Insig1Mu into oleate-treated HepG2 cells. Since oleate treatment increases miR-24 expression in HepG2 cells, as described above, it was expected that oleate treatment would lead to a decrease of luciferase activity in HepG2 cells transfected with pMiR-Insig1 compared to pMiR-Insig1Mu. In fact oleate treatment of HepG2 cells transfected with pMiR-Insig1 resulted in robust repression of luciferase activity compared to pMiR-Insig1Mu (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, we observed that the oleate treatment led to an increase of miR-24 and decrease of Insig1 (Fig. 3B), which subsequently promoted intracellular lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes (Fig. 3C,D). Similar results were also observed in HepG2 cells (Supporting Fig. 4A,B,C). These observations further suggested that miR-24 may be a critical promoter of hepatic lipid accumulation by interacting with Insig1.

Fig. 3.

MiR-24 directly represses expression of Insig1 during lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes. (A) Oleate treatment led to a decrease in luciferase activity of pMiR-Insig1 as compared with pMiR-Insig1Mu. HepG2 cells were transfected with reporter constructs pMiR-Insig1 or the mutated pMiR-Insig1Mu, and luciferase activity was determined after 24 hours of oleate treatment. (B–D) Oleate treatment led to up-regulated miR-24 and decreased Insig1 as revealed by qRT-PCR, which subsequently led to a significant increase in lipid content in human hepatocytes as displayed by Nile Red staining. (E–G) miR-24 inhibitor transfection into oleate-treated human hepatocytes antagonized the inhibitory effect of up-regulated miR-24 on Insig1 and lipid accumulation. Insig1 and miR-24 levels were determined by qRT-PCR and lipid content was measured by Nile Red staining. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

To determine loss-of-function for miR-24 in oleate-treated human hepatocytes and HepG2cells, we transfected miR-24 inhibitor into both cell types to knock down up-regulated miR-24. As expected, antagonizing miR-24 led to a significant increase of Insig1 (Fig. 3E), which further prevented lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes (Fig. 3F,G). MiR-24 knockdown in oleate-treated HepG2 cells gave similar results (Supporting Fig. 4D–F). Nonetheless, through both gain-of-function and loss-of-function in vitro assays, these data demonstrated that miR-24 was necessary and sufficient for the down-regulation of Insig1 during fatty acid treatment. Together, our results indicated that Insig1 is a direct target of miR-24 during lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells and the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 may play an important role in hepatic lipid accumulation.

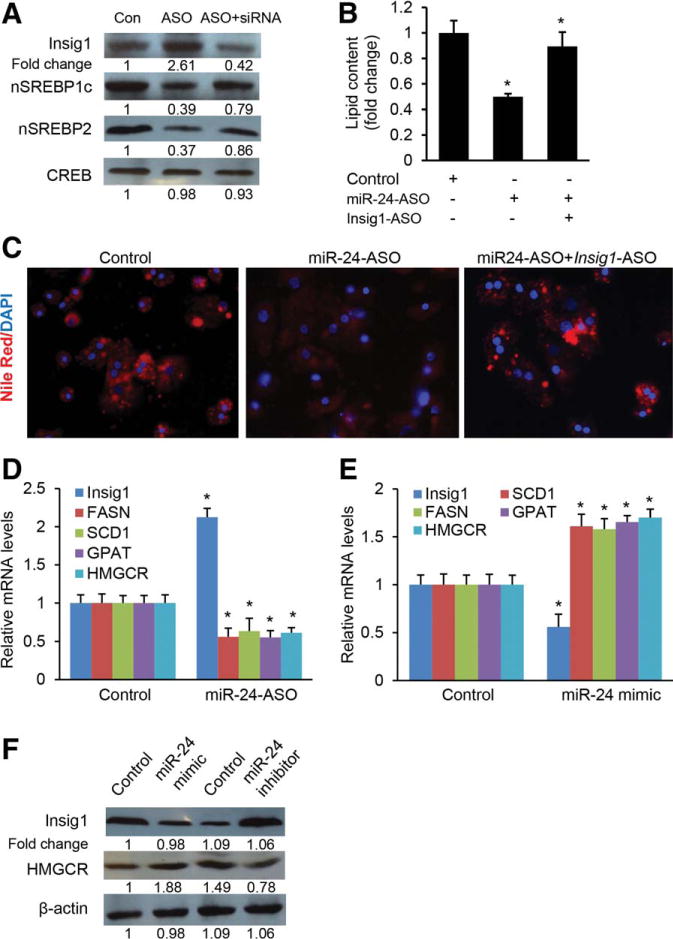

MiR-24 Facilitates SREBP Processing, Which Subsequently Increases Expression of Lipogenic Genes and Lipid Accumulation by Targeting Insig1

Overexpression of Insig1 causes inhibition of SREBP processing that is essential for high levels of lipid synthesis in the liver.17 To further confirm that the ability of miR-24 to promote SREBP processing and increase lipogenesis was mediated by Insig1, we inhibited miR-24 by transfecting miR-24-ASO into human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells to induce expression of Insig1, and then knocked down the induced Insig1 using Insig1-ASO. We found that the decreased nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2 protein levels present in the hepatocytes and HepG2 cells transfected with miR-24-ASO alone normalized after additional Insig1 knockdown (Fig. 4A; Supporting Fig. 5A), which established Insig1 as a potential key target in promoting SREBP processing. This observation led us to conclude that the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 plays a key role in hepatic lipid accumulation. To confirm this, we determined the lipid content in cells treated with miR-24-ASO before and after additional Insig1-ASO treatment. The results showed that miR-24 knockdown prevented lipid accumulation, and additional treatment of Insig1-ASO antagonized the effect of miR-24-ASO on lipid accumulation both in human hepatocytes (Fig. 4B,C) and HepG2 cells (Supporting Fig. 5B,C).

Fig. 4.

The inhibitory effect of miR-24 on lipogenesis is mediated by Insig1. (A) miR-24 knockdown in human hepatocytes led to increased protein levels of Insig1, which subsequently caused a decrease in nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2. Additional knockdown of induced Insig1 with siRNA restored levels of nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2. Human hepatocytes were treated with oleate to induce miR-24, and then miR-24-ASO was transfected into the cells to knock down the up-regulated miR-24. Nuclear SREBP1c, SREBP2, and Insig1 proteins were determined by western blot. CREB protein (cAMP-response element-binding protein) served as internal control of nuclear protein. The ImageJ program was used to quantify western blots. (B,C) miR-24 knockdown prevented lipid accumulation in human hepatocytes, and additional knockdown of Insig1 rescued the effect of miR-24-ASO. (D) Deletion of miR-24 increased expression of Insig1 in human hepatocytes, which subsequently led to a significant decrease in mRNA levels of SCD1, FASN, GPAT, and HMGCR. (E) Overexpression of miR-24 repressed expression of Insig1, which subsequently caused an increase in mRNA levels of lipogenic genes including SCD1, FASN, GPAT, and HMGCR. mRNA levels of SCD1, FASN, GPAT, and HMGCR were measured by qRT-PCR. (F) Western blots further revealed that miR-24 overexpression by transfecting miR-24 mimics into human hepatocytes increased protein levels of HMGCR, while miR-24 knockdown by miR-24 inhibitor had a reverse effect. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

SREBPs are transcription factors that activate genes encoding enzymes required for synthesis of cholesterol and triglycerides.19,20 Therefore, we analyzed expression levels of lipogenic genes including SCD1 (stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1), GPAT (glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase), and FASN (fatty acid synthase), three direct targets of SREBP1c38 as well as HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase), a target of SREBP2. We found that miR-24 knockdown led to increased Insig1, and down-regulated SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR in both human hepatocytes (Fig. 4D) and HepG2 cells (Supporting Fig. 5D). In contrast, overexpression of miR-24 prevented expression of Insig1 and up-regulated SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR (Fig. 4E; Supporting Fig. 5E). Western blot further revealed that miR-24 modulated expression of HMGCR by interacting with Insig1 (Fig. 4F). Taken together, our results indicated that miR-24-induced lipid accumulation is, in part, mediated by Insig1.

Suppression of miR-24 Expression Improves Obesity-Associated Hyperlipidemia and Fatty Liver

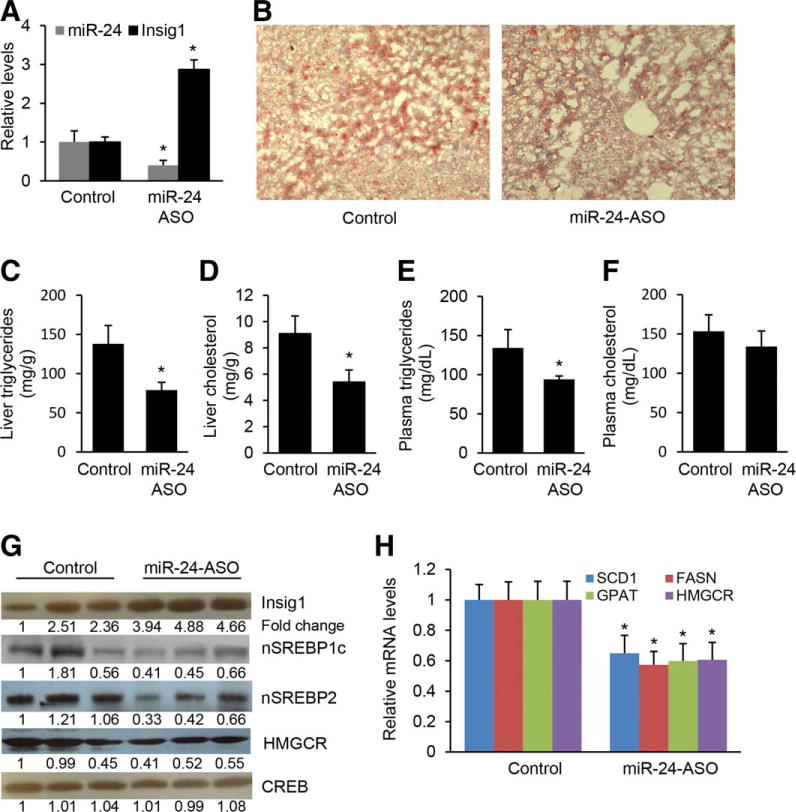

Next, we assessed the functional contribution of increased Insig1 expression to the development of fatty liver by reducing miR-24 expression in obese mice. We synthesized LNA (locked nucleic acid) anti-miR-24 ASO (anti-sense oligonucleotide) (miR-24-ASO) specifically targeting miR-24. To confirm that the phenotype observed in miR-24-ASO-injected mice was due to specific miRNA deficiency, and not toxicity caused by the ASO, we generated miR-24-mismatched-anti-sense oligo (miR-24-MM-ASO), a control ASO that differs from miRNAs in four mismatched basepairs. C57Bl/6 mice, which had been on an HFD for 8 weeks, were injected with either miR-24-ASO or miR-24-MM-ASO for 4 weeks. We observed an 88% reduction of hepatic miR-24 expression in mice that received miR-24-ASO compared to miR-24-MM-ASO, and a 3-fold increase of Insig1, as revealed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5A) and immunostaining (Supporting Fig. 6A,B). MiR-24-ASO treatment had no effect on body and liver weight (Supporting Table 5). On the other hand, antagonizing miR-24 significantly reduced high levels of triglycerides and cholesterol in liver and triglycerides in plasma in HFD animals treated with miR-24-ASO (Fig. 5B–E), in contrast to plasma total cholesterol levels (Fig. 5F). Nile Red and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining further confirmed that miR-24 knockdown reduced hepatic lipid accumulation in livers of HFD-treated mice (Supporting Fig. 6C,D). Our findings indicated that the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 plays an important role in NAFLD and hypertriglyceridemia, and miR-24-ASO may be a potential therapeutic target for both disorders.

Fig. 5.

Antagonizing miR-24 prevents hepatic lipid accumulation and hypertriglyceridemia in HFD-treated mice. (A) miR-24-ASO injection resulted in down-regulated miR-24 and increased Insig1 expression in livers of dietary obese mice. (B,C) miR-24 knockdown inhibited lipid accumulation in livers of HFD-fed mice injected with miR-24-ASO as compared to mice injected with miR-24-MM-ASO. Representative images are shown. Cellular triglyceride content was measured by Oil Red staining and triglyceride content (per mg protein) was measured with a triglyceride estimation kit. (D) miR-24 knockdown reduced hepatic cholesterol in HFD-treated mice. (E) Antagonizing miR-24 led to decreased serum triglyceride levels of HFD-fed mice treated with miR-24-ASO (n = 6) as compared to mice injected with miR-24-MM-ASOs (n = 6). (F) miR-24 knockdown had no effect on levels of serum cholesterol. (G) miR-24 knockdown in HFD-treated mice led to an increase in protein levels of Insig1 and prevented nuclear SREBPs processing, which was reflected by decreased nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2 protein levels in livers of HFD-treated mice with miR-24-ASO injection. Furthermore, HMGCR protein level was decreased due to reduced nuclear SREBP2. (H) qRT-PCR showing that HFD-treated mice with decreased levels of miR-24 also retained reduced expression of SCD1, FASN, GPAT, and HMGCR after miR-24-ASO injection. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

MiR-24 Knockdown Reduces Levels of Nuclear SREBP1C and SREBP2 Proteins and Lipogenic Enzyme mRNA in Livers of HFD-Treated Mice

Insig1 has an apparent antilipogenic action by inhibiting SREBPs processing.17,22 We therefore compared nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2 levels in livers of miR-24-ASO and miR-24-MM-ASO treated mice. As expected, western blot revealed that miR-24-ASO treatment led to a significant increase in Insig1 and reduction in SREBP1c, SREBP2 and HMGCR in the livers of HFD-treated mice (Fig. 5G). It is known that SREBP1c is a transcriptional activator of lipogenic genes including SCD1, GPAT, and FASN38 and SREBP2 is a transcriptional activator of HMGCR.20 Elevation of SREBP1c and SREBP2 due to miR-24 knockdown should promote expression of these lipogenic genes. We therefore compared the expression of SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR in livers of miR-24-ASO treated and control mice using qRT-PCR. In the miR-24-ASO treated group, the mRNA of four enzymes averaged at least 40% lower those of control group (Fig. 5H). Thus, the reduction of nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2 was associated with a dramatic reduction in the expression of the target enzymes responsible for the lipogenesis, which prevents hepatic lipid accumulation and hyperlipidemia.

In summary, our data have shown that overexpression of miR-24 led to deceased Insig1, increased nuclear SREBP1c and SREBP2, and subsequently elevated lipid accumulation in primary human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells, whereas antagonizing miR-24 led to the opposite and more therapeutic effect. We have also shown that knockdown of miR-24 in livers of HFD-treated mice produced similar effects as overexpression of Insig1, including reduced fatty liver and hypertriglyceridemia. Mechanistically, SCAP-SREBP complex is retained in the ER by the interaction between SCAP and Insig1 under normal conditions. An increase in miR-24 levels inhibits Insig1 expression, which reduces the assembly of SCAP-SREBP complexes. This then leads to translocation of SCAP-SREBP from the ER to Golgi and proteolytic processing of SREBPs, which then enter the nucleus and activate transcription of lipogenic genes (Fig. 6). Our findings and those of others have shown that miR-24.

Fig. 6.

Proposed mechanism by which miR-24 promotes hepatic lipid synthesis. Immature SREBPs form a SREBP-SCAP complex, which is retained in the ER by the interaction between SCAP and the ER-anchoring protein Insig1. By directly inhibiting Insig1 expression, miR-24 facilitates the escape of SCAP-SREBP complex from ER to Golgi, where they are processed by two membrane-bound proteases. The processed SREBP fragments are then released into the cytosol where they then enter the nucleus to activate transcription of lipogenic genes.

Discussion

Our study addresses a potentially important role for miR-24 overexpression in the development of obesity-associated NAFLD. The observation that antagonizing miR-24 expression in dietary obese mice improves these metabolic parameters clearly indicates a functional role for increased miR-24 expression in the development of obesity-associated NAFLD. Importantly, increased miR-24 expression is not restricted to murine obesity models of NAFLD, but is also detected in human NASH patients.23 Thus miR-24 and its target gene(s) may act as potential new targets for the treatment of obesity-associated NAFLD or its advanced form NASH. In addition, we also found that the binding motif of miR-24 within the Insig1 3′ UTRs is conserved between human, rat, and mouse, and overexpression of miR-24 in human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells can significantly inhibit expression of Insig1, further suggesting that our finding can be applied to human NAFLD.

Among these potential target genes, we have functionally validated Insig1 as a bona fide target of miR-24 both in vitro and in vivo. Gain-of-function and loss-of function for Insig1 causes decreased or increased total content of triglycerides in mouse livers, respectively,21,37 further indicating the important role of Insig1 in obesity-regulated fatty liver diseases. In addition, some genome-wide association studies revealed an association between Insig1 variants with the susceptibility to develop hypertriglyceridemia in humans,28 which is consistent with our finding that miR-24 knockdown normalizes triglyceride levels.

Although the role of Insig1 in metabolic diseases has been studied extensively, surprisingly few studies have addressed the role of the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 in the molecular mechanism of fatty liver diseases. Our data revealed an important role for the crosstalk between miR-24 and Insig1 in the control of hepatic lipid accumulation and hypertriglyceridemia in vivo. We demonstrated that knockdown of miR-24 led to up-regulated Insig1, down-regulated nuclear SREBP1c, and down-regulation of hepatic SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR expression. These findings are consistent with earlier reports that overexpression of Insig1 represses SREBP processing and in turn increase expression of SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR.21 It is well known that SCD1, GPAT, FASN, and HMGCR are characterized mediators of hepatic lipid accumulation in vitro and in vivo,20,39 suggesting that miR-24-evoked, Insig1-dependent inhibition of SREBP processing represents a candidate pathway to cause fatty liver and possibly hypertriglyceridemia. Although the mechanism(s) by which miR-24 controls hepatic lipid accumulation clearly requires further investigation, our study reveals an important role for the interaction between miR-24 and Insig1 in obesity-induced fatty liver disease in vivo. Our data showed that miR-24 is significantly induced in the livers of HFD-treated mice, and its knockdown has a therapeutic response for NAFLD and hypertriglyceridemia in mice. In addition, miR-24 has a conserved binding motif on the 3′ UTR of both human and mouse Insig1, and the expression of miR-24 is induced in human NASH patients,23 suggesting that antagonizing miR-24 is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of NAFLD. The ultimate purpose of our study was to develop miR-24-ASO as a therapeutic agent for NAFLD and potentially also for the treatment of hyperlipidemia. Our findings suggest, in fact, that such an approach is feasible. In addition, mice receiving miR-24-ASO treatment showed negligible effects on alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (data not shown here), suggesting its minimal hepatic toxicity. Therefore, we will further optimize the dose and duration of miR-24-ASO and investigate its therapeutic potential for NAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part from grants received from the Department of Medicine, Minnesota Medical Foundation, NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award at the University of Minnesota (UL1TR000114), and Grants-in-Aid from the University of Minnesota.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ASO

anti-sense oligonucleotide

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- GPAT

glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- Insig1

insulin-induced gene 1

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- SCAP

SREBP cleavage-activating protein

- SCD1

stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1

- SREBP

sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- TTR

transthyretin

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report

References

- 1.Calle E, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair S, Mason A, Eason J, Loss G, Perrillo RP. Is obesity an independent risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis? HEPATOLOGY. 2003;36:150–155. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaggini M, Morelli M, Buzzigoli E, DeFronzo RA, Bugianesi E, Gastaldelli A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its connection with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Nutrients. 2013;5:1544–1560. doi: 10.3390/nu5051544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunt E, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. HEPATOLOGY. 2011;53:810–820. doi: 10.1002/hep.24127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell. 2010;140:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartel D. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esau C, Davis S, Murray SF, Yu XX, Pandey SK, Pear M, et al. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack F. Oncomirs—microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya S, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethupathy P, Borel C, Gagnebin M, Grant G, Deutsch S, Elton T, et al. Human microRNA-155 on chromosome 21 differentially interacts with its polymorphic target in the AGTR1 3′ untranslated region: a mechanism for functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:405–413. doi: 10.1086/519979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie H, Lim B, Lodish H. MicroRNAs induced during adipogenesis that accelerate fat cell development are downregulated in obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1050. doi: 10.2337/db08-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornfeld J-W, Baitzel C, Köonner AC, Nicholls HT, Vogt MC, Herrmanns K, et al. Obesity-induced overexpression of miR-802 impairs glucose metabolism through silencing of Hnf1b. Nature. 2013;494:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature11793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao Y, Mohan R, Zhang S, Tang X. MicroRNAs as pharmacological targets in diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2013;75:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabe D, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Insig-2, a second endoplasmic reticulum protein that binds SCAP and blocks export of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12753–12758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162488899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong Y, Lee JN, Lee PC, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Ye J. Sterol-regulated ubiquitination and degradation of Insig-1 creates a convergent mechanism for feedback control of cholesterol synthesis and uptake. Cell Metab. 2006;3:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang T, Espenshade PJ, Wright ME, Yabe D, Gong Y, Aebersold R, et al. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in ER. Cell. 2002;110:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11041–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards PA, Tabor D, Kast HR, Venkateswaran A. Regulation of gene expression by SREBP and SCAP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelking LJ, Kuriyama H, Hammer RE, Horton JD, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, et al. Overexpression of Insig-1 in the livers of transgenic mice inhibits SREBP processing and reduces insulin-stimulated lipogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1168–1175. doi: 10.1172/JCI20978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelking LJ, Liang G, Hammer RE, Takaishi K, Kuriyama H, Evers BM, et al. Schoenheimer effect explained—feedback regulation of cholesterol synthesis in mice mediated by Insig proteins. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2489–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung O, Puri P, Eicken C, Contos MJ, Mirshahi F, Maher JW, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with altered hepatic micro-RNA expression. HEPATOLOGY. 2008;48:1810–1820. doi: 10.1002/hep.22569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahrens M, Ammerpohl O, von Schöonfels W, Kolarova J, Bens S, Itzel T, et al. DNA methylation analysis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease suggests distinct disease-specific and remodeling signatures after bariatric surgery. Cell Metab. 2013;18:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman R, Farh K, Burge C, Bartel D. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krek A, Grün D, Poy M, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein E, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J-H, Li J-H, Shao P, Zhou H, Chen Y-Q, Qu L-H. starBase: a database for exploring microRNA—mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D202–D209. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith EM, Zhang Y, Baye TM, Gawrieh S, Cole R, Blangero J, et al. INSIG1 influences obesity-related hypertriglyceridemia in humans. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:701–708. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reimand J, Kull M, Peterson H, Hansen J, Vilo J. g: Profiler—a web-based toolset for functional profiling of gene lists from large-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W193–200. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNa-seIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postic C, Magnuson MA. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26:149–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<149::aid-gene16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakai H, Fuess S, Storm TA, Muramatsu S, Nara Y, Kay MA. Unrestricted hepatocyte transduction with adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vectors in mice. J Virol. 2005;79:214–224. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.214-224.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmen J, Lindow M, Silahtaroglu A, Bak M, Christensen M, Lind-Thomsen A, et al. Antagonism of microRNA-122 in mice by systemically administered LNA-antimiR leads to up-regulation of a large set of predicted target mRNAs in the liver. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1153–1162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez-Lechon MJ, Donato MT, Martínez-Romero A, Jiménez N, Castell JV, O’Connor J-E. A human hepatocellular in vitro model to investigate steatosis. Chemico-bio Inter. 2007;165:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaishi K, Duplomb L, Wang M-Y, Li J, Unger RH. Hepatic insig-1 or-2 overexpression reduces lipogenesis in obese Zucker diabetic fatty rats and in fasted/refed normal rats. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7106–7111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401715101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin ES, Lee HH, Cho SY, Park HW, Lee SJ, Lee TR. Genistein downregulates SREBP-1 regulated gene expression by inhibiting site-1 protease expression in HepG2 cells. J Nutrition. 2007;137:1127–1131. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendez-Sanchez N, Arrese M, Zamora-Valdes D, Uribe M. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2007;27:423–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.